Abstract

Single incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) is a rapidly developing field that may represent the future of laparoscopic surgery. The major advantage of SILS over standard laparoscopic surgery is in cosmesis, with surgery becoming essentially scarless if the incision is hidden within the umbilicus. Only one incision is required so the risk of potential complications like port site hernias, haematomas and wound infection is reduced. The trade-off for this is a technically more challenging procedure with different underlying principles to that of traditional laparoscopic surgery. A wide variety of new equipment has been developed to support SILS and the range of procedures that are amenable to the technique is increasing. To date most of the published data relating to SILS are in the form of case series, with the first large randomised controlled trials due to be completed by the end of 2012. The existing evidence suggests that SILS is similar to standard laparoscopic surgery in terms of complication rates, completion rates and post-operative pain scores. However, the duration of SILS is longer than equivalent laparoscopic procedures. This article discusses SILS with regard to its applications in general surgery and reviews the evidence currently available.

Keywords: Single, Port, Laparoscopy, Surgery

Laparoscopic surgery has become the gold standard for many operative procedures in the last 20 years. Its advantages over open surgery are well documented; however, the drive to reduce the trauma of surgical access persists. Laparoscopic techniques utilising only one umbilical port may represent the next step in this surgical evolution. They have been given a myriad of names (single-port access surgery (SPA), one-port umbilical surgery (OPUS), transumbilical endoscopic surgery (TUES) etc) since their inception, with no standardised acronym to date.1

Single incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) is an umbrella term used in this article to encompass all such single incision laparoscopic techniques, which allow potentially ‘scarless’ surgery as the wound is hidden within the umbilicus. Many groups have reported on the feasibility of the technique and its initial success but there have been very few significant trials. There is still no consensus and this field therefore represents a major focus for research and development. A MEDLINE® search using multiple Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms pertaining to this topic highlighted 464 relevant articles in the literature. This article aims to present the current possibilities offered by this technique within general surgery and the evidence supporting it.

Discussion

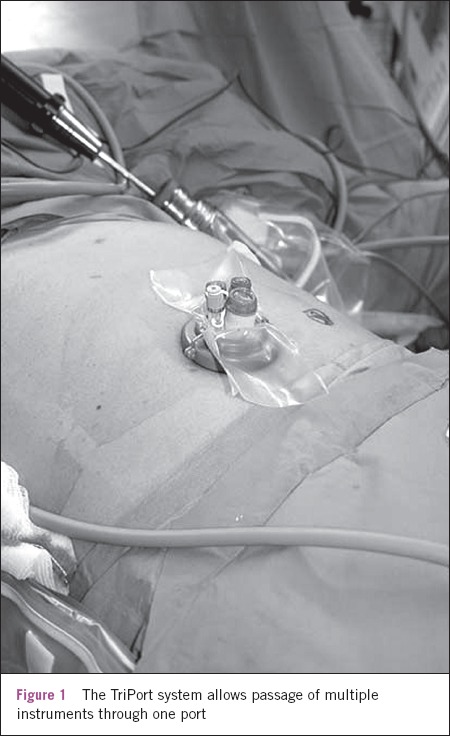

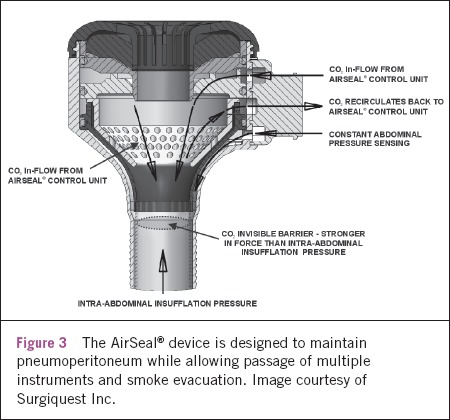

There is still much debate over whether SILS is the future of laparoscopic surgery or just a passing fad. SILS was first described in general surgery in 1997 to perform laparoscopic cholecystectomies1,2 and appendicectomies1,3 but enthusiasm was limited because of poor equipment and technical support. In 2005 a resurgence was initiated in urology by Hirano et al.4 Technical improvements that enabled this revival included bent or articulating instruments, adjustments in laparoscopes, several adjacently placed trocars through one incision and special multilumen ports that allow simultaneous multiple instrument insertion.1 Many of the big healthcare manufacturers have seen this emerging market and new operative hardware is being developed to facilitate the technique. Devices like the TriPort (Advanced Surgical Concepts, Wicklow, Ireland) (Fig 1), the AirSeal® (SurgiQuest Inc, Orange, CT, US) (Fig 3) and the SILS™ port (Covidien, Norwalk, CT, US) have made single site surgery easier and more efficient.1,5

Figure 1.

The TriPort system allows passage of multiple instruments through one port

Figure 3.

The AirSeal® device is designed to maintain pneumoperitoneum while allowing passage of multiple instruments and smoke evacuation. Image courtesy of Surgiquest Inc.

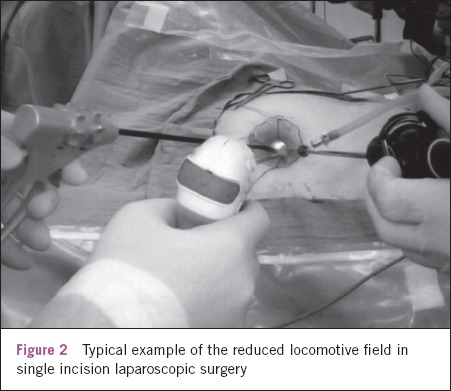

Figure 2.

Typical example of the reduced locomotive field in single incision laparoscopic surgery

A return to SILS cholecystectomies followed and this is the most studied general surgery procedure using the technique. However, the repertoire of operations amenable to SILS is expanding and recently published papers describe SILS approaches for totally extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair,6 appendicectomy,7 Heller myotomy,8 adrenalectomy,4 right hemicolectomy,9 sigmoidectomy,10 gastric banding,11 sleeve gastrectomy12 and splenectomy.13

Advantages of SILS over current laparoscopic practice are based on the reduced number of necessary incisions. There is a consequent reduction in associated morbidity including wound infection, pain, bleeding, visceral injury and port site herniation. Furthermore, cosmesis is improved, with many of the newer techniques using incisions within the umbilicus so that surgery is virtually ‘scarless’.1,6,10,14

However, the SILS technique does not rely on triangulation, which is one of the core principles in conventional laparoscopic surgery, allowing adequate operative exposure while maintaining an ergonomic position for the surgeon and assistant.14 Consequently, the inherent technical challenge that arises from the SILS technique or ‘in-line viewing’ is that of a compromised view and locomotive field.

The external area within which the surgeon's hands are located is much smaller than in standard laparoscopic surgery.1 Movement of the camera often results in inadvertent movement of an adjacent instrument, which can make even simple tasks very difficult. Other practical difficulties in SILS procedures include problems in maintaining pneumoperitoneum and how to release diathermy smoke.1,14

The problems with SILS are thus twofold: the technical challenge presented by the procedure, and the ability and willingness of the surgeon to adapt to it. These difficulties will be reduced in time with increasing experience and the introduction of new specialised equipment including multilumen ports, angled scopes, articulated instruments and instruments of variable length.1,14 SILS now seems likely to follow the path that laparoscopic surgery took 20 years ago with initial skepticism followed by rapid uptake and development. It may even replace laparoscopic procedures like cholecystectomy as the gold standard in years to come as an evidence base starts to build.

Evidence for SILS

SILS is a developing field and, to date, the various publications relating to the technique are mostly case reports or small case series describing the feasibility and technical difficulties of different operations. There are very few studies comparing SILS to standard laparoscopic procedures and there is a need for randomised controlled trials to definitively prove that SILS is no different from standard laparoscopic surgery in terms of completion rates and complications but with the advantage of being more cosmetic with subsequently reduced morbidities including pain. A number of research groups in the US have registered randomised controlled trials and are currently recruiting patients. These include studies comparing standard laparoscopic cholecystectomies, appendicectomies and colectomies to the SILS equivalents. They promise to deliver much needed answers but are years from completion.

The studies to date have a number of other flaws limiting their impact. These include low sample size, selection bias and difficulty in blinding the participants. The vast majority of studies have a very carefully selected SILS cohort of non-complicated cases, which significantly limits their generalisability. The procedures with the most published evidence are cholecystectomy and appendicectomy.

Table 1.

Some of the technical challenges involved in a SILS cholecystectomy15

| Challenge | Solution | Problems |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Restricted number of working instruments | Single, large device with multiple ports or multiple ports through a single incision | Restricted movements and clashing of instruments |

| Increased potential for development of fascial defects | ||

| Difficulty maintaining pneumoperitoneum | ||

| No escape for smoke created by tissue cauterisation | ||

| 2. Introduction of single, large or multiple ports | Development of circumferential skin flaps | Potential for subcutaneous haematoma or seroma formation |

| 3. Loss of triangulation with straight instruments | Angulated instruments | Requires training and adjustment |

| Semirigid instruments | ‘Bending’ during retraction/dissection | |

| 4. Suboptimal exposure of Calot's triangle | Retraction with hooks, stay sutures and/or percutaneous gallbladder drainage | Potential for bactobilia and biliary leaks with bile peritonitis |

Cholecystectomy

Langwieler et al showed in a small case series of 14 single port cholecystectomies that this method was successfully completed in all cases with no additional complications although it took longer (53–115 minutes) than a standard laparoscopic cholecystectomy.15

Furthermore, Hong et al completed a similar case series of 15 well selected SILS cholecystectomies in patients with a body mass index as high as 34kg/m2.16 Their patients had a similar duration of post-operative hospital stay compared with standard laparoscopic cholecystectomy patients with no observed complications although they too reported longer operative times (35–165 minutes).

In one of the few randomised controlled trials performed to date, Tsimoyiannis et al randomised 40 patients to either SILS cholecystectomy or standard cholecystectomy with the main outcome measure being pain scores.17 This prospective double blind trial found significant differences in pain score in favour of the SILS method from 12 hours after surgery for abdominal pain and from 6 hours after surgery for shoulder tip pain. The SILS group reported no pain after 24 hours. A statistically significant difference was also shown in duration of operation with the standard 4-port technique being 12 minutes quicker on average. All other outcomes were not significantly different. Obviously, this trial has limited worth owing to its low power and, like most of these studies, it suffers from selection bias.

The largest case series to date reported 297 cases across multi-institutional and multi-national centres.18 The data also confirm that SILS cholecystectomies are comparable to standard laparoscopies in terms of length of stay, blood loss and complications but with the advantage of better cosmesis. Again, the SILS technique was shown to be slower than the standard technique. Post-operative pain was not commented on. The study concluded that SILS is an effective and efficient alternative to standard laparoscopic cholecystectomies. Erbella and Bunch found similar results in their case series of 100 patients.19

Appendicectomy

Vidal et al performed a four-month prospective study comparing data for patients undergoing SILS appendicectomies to standard laparoscopic appendicectomies.6 Each group contained 15 patients and the SILS appendicectomy was successfully completed in all cases. None required conversion to standard laparoscopic or open methods. The mean operating time of 51 minutes in the SILS group was not significantly different from the 46 minutes in the standard laparoscopic appendicectomy group. Both groups had similar post-operative durations of stay and pain scores.

In contrast, in a series of 55 SILS appendicectomies reported by Chouillard et al, 25% of the cases had to be converted to standard laparoscopic or open procedures, mostly owing to difficulties exposing the appendix.20 They found lower pain scores and better cosmesis in the SILS group and felt that it was a suitable alternative to standard laparoscopic appendicectomy in uncomplicated cases of appendicitis despite the additional time required.

A second prospective randomised controlled trial performed in Korea with 40 participants found increased postoperative pain in the SILS group but again concluded that SILS was a suitable alternative to a standard 3-port laparoscopic appendicectomy as the other outcome measures were not significantly different between the two groups.21

Conclusions

The concept of performing laparoscopic surgery through a single incision is gaining momentum among patients, surgeons and the industry alike. It seems likely that the public will demand this even less invasive approach in much the same way that it forced the explosion of laparoscopic surgery two decades ago. However, as surgeons, we should not advocate for slightly improved cosmetic value over safety.5,14 Although a number of the studies listed have shown hardly any difference compared to conventional laparoscopic surgery, we still require a series of large multicentre randomised controlled trials to prove the efficacy and safety of SILS. To date, the evidence we have suggests that SILS procedures are comparable to standard laparoscopic techniques at least for uncomplicated biliary or enteric pathologies. Furthermore, increasing experience of SILS will continue to innovate to further improve the ergonomics, feasibility and range of the technique.

References

- 1.Romanelli JR, Earle DB. Single port laparoscopic surgery: an overview. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1,419–1,427. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0463-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chow A, Purkayastha S, Aziz O, Paraskeva P. Single-incision laparoscopic surgery for cholecystectomy: an evolving technique. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:709–714. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0655-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esposito C. One-trocar appendectomy in pediatric surgery. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:177–178. doi: 10.1007/s004649900624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirano D, Minei S, Yamaguchi K, et al. Retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomy for adrenal tumors via a single large port. J Endourol. 2005;19:788–792. doi: 10.1089/end.2005.19.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castellucci SA, Curcillo PG, Ginsberg PC, et al. Single port access adrenalectomy. J Endourol. 2008;22:1,573–1,576. doi: 10.1089/end.2008.0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Filipovic-Cugura J, Kirac I, Kulis T, et al. Single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) for totally extraperitoneal (TEP) inguinal hernia repair: first case. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:920–921. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0318-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vidal O, Valentini M, Ginestà C, et al. Laparoscopic single-site surgery appendectomy. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:686–691. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0661-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saba SC, Curcillo PG. Single-port access (SPA) surgery: intracorporeal liver retractor for SPA Heller myotomy. Surg Endosc. 2008;22(Suppl 1):S285. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Remzi FH, Kirat HT, Kaouk JH, Geisler DP. Single-port laparoscopy in colorectal surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:823–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leroy J, Cahill RA, Peretta S, Marescaux J. Single port sigmoidectomy in an experimental model with survival. Surg Innov. 2008;15:260–265. doi: 10.1177/1553350608324509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen NT, Hinojosa MW, Smith BR, Reavis KM. Single laparoscopic incision transabdominal (SLIT) surgery – adjustable gastric banding: a novel minimally invasive surgical approach. Obes Surg. 2008;18:1,628–1,631. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9705-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saber AA, Elgamal MH, Itawi EA, Rao AJ. Single incision laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (SILS): a novel technique. Obes Surg. 2008;18:1,338–1,342. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9646-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Targarona EM, Lima MB, Balague C, Trias M. Single-port splenectomy: current update and controversies. J Minim Access Surg. 2011;7:61–64. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.72383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chamberlain RS, Sakpal SV. A comprehensive review of single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) and natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) techniques for cholecystectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1,733–1,740. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0902-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langwieler TE, Nimmesgern T, Back M. Single-port access in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1,138–1,141. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0389-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong TH, You YK, Lee KH. Transumbilical single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy: scarless cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1,393–1,397. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0252-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsimoyiannis EC, Tsimogiannis KE, Pappas-Gogos G, et al. Different pain scores in single transumbilical incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus classic laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1,842–1,848. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-0887-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gurcillo PG 2nd, Wu AS, Podolsky ER, et al. Single-port-access (SPA) cholecystectomy: a multi-institutional report of the first 297 cases. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1,854–1,860. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0856-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erbella J Jr, Bunch GM. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: the first 100 outpatients. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1,958–1,961. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-0886-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chouillard E, Dache A, Torcivia A, et al. Single-incision laparoscopic appendectomy for acute appendicitis: a preliminary experience. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1,861–1,865. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0860-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park JH, Hyun KH, Park CH, et al. Laparoscopic vs transumbilical single-port laparoscopic appendectomy; results of prospective randomized trial. J Korean Surg Soc. 2010;78:213–218. [Google Scholar]