Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Increasing numbers of joint arthroplasty are performed in Britain. While associated complications are well documented, it is not known which of those initiate malpractice claims.

METHOD

A five-year period was assessed for trends to highlight areas for further improvement in patient information and surgical management.

RESULTS

The National Health Service paid out almost £14 million for 598 claims. Forty per cent of this was for legal costs. The number of claims increased over time while the rate of successful claims decreased.

CONCLUSIONS

A failure to consent adequately and to adhere to policies and standard practice can result in a successful malpractice claim. Protecting patients intrao-peratively and maintaining high technical expertise while implementing policies and obtaining informed consent decreases the litigation burden.

Keywords: Arthroplasty, Litigation, Hip, Knee, Orthopedics

The number of surgical procedures performed to improve quality of life has risen owing to a growing population and increasing patient expectations. Healthcare has become part of the modern consumerist society and providers include those that are state subsidised, such as the National Health Service (NHS).

Joint replacement surgery is one of the areas with the most benefit in terms of cost effectiveness and patient satisfaction.1,2 Regardless of its high success rates, there are inevitably patients who are dissatisfied with the final outcome owing to the perceived harm caused by a surgeon or errors during the patients' medical care. The proportion of dissatisfied patients can be as high as 28%.1,3 Malpractice claims are therefore a painful reality for orthopaedic surgeons, who fall behind only obstetricians and general surgeons for actual claim rates.4,5 Over a 13-year period the financial cost to the US came to $560.2 million.4 The increase in litigation costs is a worldwide trend.5,6

The instigation of a malpractice claim can be multifactorial. Communication skills can be pivotal as the setting of realistic expectations and the honest relaying of medical errors is crucial.3,7 Other factors include misdiagnoses and failure to diagnose and treat complications in a timely and appropriate manner. However, there may also be a financial element motivating malpractice claims, both by the patient and the associated legal profession.4

Within the NHS, malpractice is indemnified by the National Health Service Litigation Authority (NHSLA) for all hospital trusts. In 2007–2008 the NHSLA made payments totalling £661 million, of which £165 million (25%) was for legal costs.8 Reforms to the civil proceedings attempted to make the system less adversarial and more efficient.6 However, the value of claims paid is often independent of the presence of negligence.9 Although the NHSLA manages the legal implications of a malpractice claim, a failure to disseminate lessons to the orthopaedic community reduces the effectiveness of a system of punitive damages to redress a medical error beyond the surgeon and institution involved. This represents a failure of clinical governance10 and good medical practice as described by the General Medical Council.11

This paper aims to quantify the cost of malpractice claims from arthroplasty surgery within the NHS and attempts to identify instigating factors and payout costs over a five-year period. This may emphasise areas of development needed in patient information and surgical management so that increased financial input enhances care and may on balance be more cost effective in the current financial climate.

Methods

Through the Freedom of Information Act 2000, data were obtained from the NHSLA of malpractice claims for hip and knee joint arthroplasty from 2002 (when all claims were managed centrally regardless of cost) to 2007, allowing time for cases to be resolved. The ratio of procedures performed to the number of claims was calculated for four years from when the British National Joint Registry came into existence in 2003.12

The data provided legal annotations identifying the factor instigating a malpractice claim and any other specific details were also recorded alongside financial costs. Joint arthroplasty secondary to trauma or revision surgery was excluded.

Instigating factors can be broadly categorised into those caused by the surgeon, post-operative medical care and the management of complications. However, under each of these headings there are specific issues that have been described as separate instigating factors (eg leg length discrepancy) as they are of specific clinical interest to surgeons. The instigating factors were assigned to each case by a single senior orthopaedic trainee (MAB) to maintain consistency. They are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Data were analysed in SPSS® v15.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, US).

Table 1.

Instigating factors for hip arthroplasty malpractice claims, their distribution, rates of successful litigation and associated costs

| Instigating factor | Number of cases | Percentage defended | Total cost | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total registered | Total closed | Defended | Claimant paid | |||

| Infection | 43 | 32 | 20 | 12 | 63% | £1,686,019 |

| Fracture | 21 | 19 | 8 | 11 | 42% | £818,438 |

| Nerve injury | 69 | 54 | 37 | 17 | 69% | £1,827,106 |

| Vascular injury | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 67% | £48,300 |

| Thromboembolic | 6 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 80% | £45,432 |

| Operator error | 50 | 40 | 7 | 33 | 18% | £2,326,820 |

| Non-operative site injury | 10 | 10 | 3 | 7 | 30% | £134,093 |

| Ongoing pain | 48 | 33 | 31 | 2 | 94% | £150,002 |

| Post-operative care | 22 | 16 | 5 | 11 | 31% | £473,096 |

| Leg length discrepancy | 41 | 32 | 21 | 11 | 66% | £885,368 |

| Dislocation | 30 | 20 | 19 | 1 | 95% | £88,594 |

| Stiffness | 7 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 71% | £74,808 |

| Total | 352 | 271 | 162 | 109 | 60% | £8,558,076 |

Table 2.

Instigating factors for knee arthroplasty malpractice claims, their distribution, rates of successful litigation and associated costs

| Instigating factor | Number of cases | Percentage defended | Total cost | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total registered | Total closed | Defended | Claimant paid | |||

| Infection | 44 | 32 | 14 | 18 | 44% | £1,239,847 |

| Fracture | 5 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 40% | £58,728 |

| Nerve injury | 17 | 15 | 8 | 7 | 53% | £330,107 |

| Vascular injury | 5 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 20% | £528,917 |

| Thromboembolic | 8 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 50% | £124,647 |

| Operator error | 57 | 40 | 25 | 15 | 63% | £902,474 |

| Non-operative site injury | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 50% | £19,726 |

| Ongoing pain | 58 | 35 | 21 | 14 | 60% | £1,385,158 |

| Post-operative care | 43 | 29 | 13 | 16 | 45% | £719,811 |

| Leg length discrepancy | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 100% | £0 |

| Dislocation | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0% | £0 |

| Stiffness | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 50% | £56,465 |

| Total | 246 | 172 | 90 | 82 | 52% | £5,365,880 |

Results

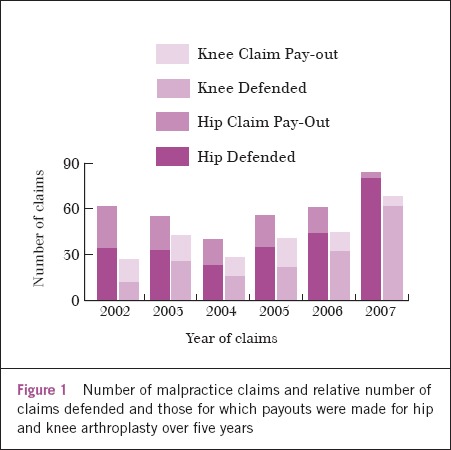

A total of 598 primary joint arthroplasty malpractice cases (352 hip and 246 knee replacements) were managed by the NHSLA between 2002 and 2007. Excluding a slight dip in 2004, claims and the ratio of claims to procedures performed have increased over time (Figs 1 and 2). The total financial cost for primary arthroplasty malpractice claims amounted to £13,923,956 with £8,558,076 for hips (mean: £75,022, range: £1,000–£448,335) and £5,365,880 for knees (mean: £64,904 range: £500–£415,093).

Figure 1.

Number of malpractice claims and relative number of claims defended and those for which payouts were made for hip and knee arthroplasty over five years

For hip claims, 271 (77%) had reached a conclusion, of which 109 (40%) resulted in payouts. Similarly, for knee claims, 171 (70%) were finalised, of which 81 (47%) resulted in payouts. The mean legal costs for malpractice claims for hip and knee arthroplasty when successfully defended were £2,335 and £1,207 respectively. When a payout was made these became £28,162 and £26,356, equating to 38% and 41% of the total mean cost to the NHS. Although the number of claims increased over the years, the rates of payout decreased (Fig 1). The costs and rates of payout of instigating factors were assessed (Tables 1 and 2).

Hip arthroplasty claims

Factors commonly instigating hip malpractice claims are listed in Table 1. Nerve injury (20%), operator error (14%) and ongoing pain (14%) were the three most common causes for hip claims. However, those likely to result in payout of a malpractice claim were operator error (82%), non-operative site injury (70%) and post-operative care (69%).

Seventy per cent of claims for nerve injury were regarding the sciatic nerve and consequent foot drop, and a single large payout was made for a failure to refer a complex primary case to a ‘specialist centre’. Ongoing pain commonly instigated claims but was well defended except when a failure of the consenting process was identified. This was also true for leg length discrepancies or when a prior agreement for specific implants was changed intra-operatively.

Claims for thromboembolic events were low and without issues of consent. However, payouts occurred from a failure to adhere to local hospital protocols. Non-operative site injuries included lacerations produced during the handling of patients in theatre or those from diathermy use. For postoperative care, failure to continue to provide a high level of care on the ward, with lack of observations and falls out of bed, and failure to obtain post-operative check radiographs produced payouts.

Knee arthroplasty claims

Factors commonly instigating knee malpractice claims are listed in Table 2. Ongoing pain (24%), operator error (23%) and infection (18%) were the three most common causes for knee claims. Nevertheless, the instigating factors likely to result in a payout were vascular injury (80%), fracture (60%) and infection (56%) with rates of payout for ongoing pain and operator error at 40% and 37% respectively.

Failure in the consenting process for ongoing pain caused a payout in 29% of claims and operator error a payout in 34% of claims on the basis of incorrect sizing of implants/side and poor technique necessitating revision surgery. Infection was a common instigator and 30% of these cases led to limb amputation, with one case of inadequate equipment sterilisation. Post-operative care was a significant issue relating to poor nursing care or physiotherapy input and a failure to follow hospital protocols produced successful claims for thromboembolic complication. Popliteal vessel injury requiring an above knee amputation and a hallux amputation due to unrecognised peripheral vascular disease also resulted in payouts.

Discussion

Joint arthroplasty improves an individual's quality of life. Greater numbers of procedures are performed annually, possibly owing in part to an expansion of criteria (eg younger patients and those with less severe pain).2 Like other specialties, orthopaedics experiences malpractice claims that are contributed to by increasing expectations and an increasingly litigious society. Although the registered number of claims is a fraction of the procedures performed, they represent a failure in practice and present avenues to develop and enhance surgical care.

Our study identified an upward trend in malpractice claims within the British system as has been described globally.5 Concurrently, the rate of successful claims has decreased (Fig 1) although anonymity of the data prevented further analysis. Overall, 1 in 2 claims resulted in a payout compared with 1 in 4 in the US2 and 1 in 3 in Germany.5 The legal costs accounted for only 40% of settlements in Britain compared with 54% in the US and the legal costs per case in the UK were on average also less than in the US.13

Although the merits of each claim may vary, there are common themes resulting in a payout. Foremost, regardless of the instigating factor, a failure of the consenting process, which establishes the patient's autonomy and right to self-determination,14 will result in a payout. The importance of consent was emphasised with the standardisation of consent documentation by the Department of Health in 200215 and, more recently, consent forms specific to orthopaedics.2,16 Together with meticulous documentation of each clinical meeting and operative notes, this may be the only defence for the surgeon against accusations of negligence.4,6

Hospital protocols and clinical pathways endeavour to standardise treatments. The focus of these protocols (whether they are based on best evidence and practice or on the most cost-effective solution for any particular institution) is dependent on the group creating them.17 This study identified that these policies are used as a surrogate for an expert witness to show that there has been a failure to adhere to a ‘standard of care’, resulting in a payout of claims in up to 25% of cases. They are used to apportion blame rather than exonerate even though the adherence to such guidelines can be as low as 25%.17 Examples include the failure to apply thromboembolic deterrent stockings to a patient although no consensus exists for the prevention of deep vein thrombosis in the literature. Deviation from such policies should be meticulously documented and accepted by a body of peers.

Finally, correct site surgery remains an ongoing risk for claims1 as in our study. A recent review has implemented protocols18 as part of initiatives by the World Health Organization.19 However, the responsibility lies ultimately with the surgeon that the correct patient is operated on, the correct site is identified and the correct procedure is performed. Failure of this will result in a payout of a malpractice claim.

The greatest liability for a surgeon is his or her technical ability to perform a procedure; operator error accounts for 40% of claims within the literature.1,4 In our study this was the second most common cause for a malpractice claim. However, if the figures for factors such as fracture, nerve injury, vascular injury, leg length discrepancy and dislocation (which could also be classified as operator error ‘subgroups’) are combined with the figures for operator error, this becomes 61% and 35% of the total registered claims for hip and knee arthroplasty respectively.

Similarly, an operator error claim was more likely to be associated with a payout for hip (82%) than knee (37%) arthroplasty, possibly highlighting the difficulties faced in surgical exposure and implantation for hip arthroplasty and why nerve injuries are the most common instigating factor in hip malpractice claims in our series and others.2 Confirmation of surgical skills acquired through training early in a career or high surgical volumes for experienced surgeons may protect the surgeons from the allegation of incompetence. It is imperative that surgeons are aware of their limitations and refer accordingly to ‘specialist centres’.1

This study highlights high payout rates for non-operative site injuries and post-operative care. We must ensure that we work in tandem with other healthcare professionals, guaranteeing the highest standard of care both inside and out of the operating theatre with clear post-operative instructions. Finally, there are inevitable catastrophes and, alongside consequences for the patient and surgeon, there will be large financial payouts in malpractice claims, such as a claim regarding popliteal vessel injury leading to an above knee amputation costing £415,000.

This is the first study in the literature analysing litigation for elective joint arthroplasty in the NHS from objective records. It attempts to identify factors likely to result in a payout for a malpractice claim. While the NHSLA manages claims medicolegally, the data have yet to be fed back nationally to arthroplasty surgeons to improve patient care. The lengthy process of feeding back data may be exacerbated by the fact that it takes an average of two to four years to resolve cases,6 similar to the five years it takes in the US.13 Weaknesses of this study include the legal nature of annotation assessed and the anonymity, precluding assessment of surgeon demographics.

Conclusions

Adequate consent may facilitate realistic expectations of surgical intervention and the potential risks undertaken. Ensuring that all stages of care are delivered to a high standard with expert technical execution of the surgery, strict adherence to the prevailing defined standards of care with timely evidence-based patient treatment, rapid recognition and treatment of complications, and detailed documentation in medical records will not only improve the quality of patient care but also serve as a strong legal defence should the need arise.

A case of publication malpractice has recently come to light at the Annals. The editorial board wishes to publicise the facts and to remind readers and potential contributors that dual publication is considered serious publication malpractice and that it is our policy, after investigation of the facts, to make public such cases and if appropriate to report them to the relevant authorities.

A paper was submitted to the Annals on the 14 November 2010. This paper was sent to review but for various reasons the editors were unable to reach a decision and it was sent out to a third reviewer. This reviewer commendably reviewed the recent literature on the subject and discovered an identical paper published in January 2011 with the same single authorship.1 That publication carries a submission date identical to the date of submission to the Annals.

The editor of the Annals asked the author of these two submissions to explain how one paper came to be submitted to two journals. His reply was inconsistent with the facts. He stated that he had submitted to the Annals but had grown tired of waiting for a response from us and had subsequently submitted to the other journal. This is not consistent with the fact that the paper was submitted to the two journals on the same day.

Dual submission is unacceptable. It duplicates the time and effort of editors and reviewers to no purpose and it indicates an intention to go ahead to dual publication. The Committee on Publication Ethics has published guidance for authors and editors, and any author is advised to read this guidance.2

The Annals is committed to maintaining the highest possible standards in publication and will continue to publicise the facts of any case of publication malpractice which is brought to our attention.

1. Bishay, SNG. Reconstruction of acute closed traumatic extensor hallucis longus tendon rupture in adolescents with spastic cerebral palsy. J Child Orthop 2011; 5: 315. (DOI 10.1007/s11832-011-0325-7).

2. Code of Conduct. Committee on Publication Ethics http://publicationethics.org/static/1999/1999pdf13.pdf (cited August 2011).

References

- 1.Attarian DE, Vail TP. Medicolegal aspects of hip and knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;433:72–76. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000159765.42036.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Upadhyay A, York S, Macaulay W, et al. Medical malpractice in hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(6 Suppl 2):2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwappach DL, Koeck CM. What makes an error unacceptable? A factorial survey on the disclosure of medical errors. Int J Qual Health Care. 2004;16:317–326. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzh058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gould MT, Langworthy MJ, Santore R, Provencher MT. An analysis of orthopaedic liability in the acute care setting. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;407:59–66. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200302000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Traina F. Medical malpractice: the experience in Italy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:434–442. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0582-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gidwani S, Zaidi SM, Bircher MD. Medical negligence in orthopaedic surgery: a review of 130 consecutive medical negligence reports. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:151–156. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B2.21567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adamson TE, Tschann JM, Gullion DS, Oppenberg AA. Physician communication skills and malpractice claims. A complex relationship. West J Med. 1989;150:356–360. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.NHS Litigation Authority. Factsheet 2: Financial Information. London: NHSLA; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris JA Jr, Carrillo Y, Jenkins JM, et al. Surgical adverse events, risk management, and malpractice outcome: morbidity and mortality review is not enough. Ann Surg. 2003;237:844–851. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000072267.19263.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clinical governance. Department of Health. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publichealth/Patientsafety/Clinicalgovernance/index.htm (cited May 2011)

- 11.Good Medial Practice: Duties of a doctor. General Medial Council. http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/good_medical_practice/duties_of_a_doctor.asp (cited May 2011)

- 12.NJR StatsOnline. National Joint Registry. http://www.njrcentre.org.uk/njrcentre/Healthcareproviders/Accessingthedata/StatsOnline/NJRStatsOnline/tabid/179/Default.aspx (cited May 2011)

- 13.Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2,024–2,033. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa054479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.General Medical Council. Consent: Patients and Doctors Making Decisions Together. London: GMC; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Department of Health. London: DH; 2002. Consent Form 1: Patient Agreement to Investigation or Treatment. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atrey A, Leslie I, Carvell J, et al. Standardised consent forms on the website of the British Orthopaedic Association. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:422–423. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B4.20497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moses RE, Feld AD. Legal risks of clinical practice guidelines. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:7–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.High Quality Care for All. London: 2008. Cm7432. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_085825. [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. 1st edn. Geneva: WHO; 2008. Surgical Safety Checklist. [Google Scholar]