Abstract

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a cholestatic liver disease of autoimmune origin, characterised by the destruction of small intrahepatic bile ducts. The disease has an unpredictable clinical course but may progress to fibrosis and cirrhosis. The diagnostic hallmark of PBC is the presence of disease-specific antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA), which are pathognomonic for the development of PBC. The disease overwhelmingly affects females, with some cases of male PBC being reported. The reasons underlying the low incidence of males with PBC are largely unknown. Epidemiological studies estimate that approximately 7–11% of PBC patients are males. There does not appear to be any histological, serological, or biochemical differences between male and female PBC, although the symptomatology may differ, with males being at higher risk of life-threatening complications such as gastrointestinal bleeding and hepatoma. Studies on X chromosome and sex hormones are of interest when studying the low preponderance of PBC in males; however, these studies are far from conclusive. This paper will critically analyze the literature surrounding PBC in males.

1. Introduction

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a chronic cholestatic liver disease characterised by an immunomediated inflammatory destruction of the small intrahepatic bile ducts, with fibrosis progressing to cirrhosis and subsequent liver failure [1–3]. The disease predominantly affects women (90% of patients) in middle age [1–4]. Studies from the United Kingdom suggest that PBC is the most frequent autoimmune liver disease, followed by autoimmune hepatitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis [5]. The incidence and prevalence of PBC appear to be rising in several countries [5–7]. Differences in the clinical course of the disease have been noted between Caucasian, African American, and Hispanic patients in the USA, with cirrhosis presenting more frequently in non-Caucasian patients [8]. Migration studies indicate that an individual's risk for PBC changes to be in accordance with the local population into which they move. This has led to the appreciation that environmental factors play an important role in the development of the disease [6, 9, 10].

Patients with PBC can be either asymptomatic with normal biochemistry tests or asymptomatic with abnormal biochemical blood tests, symptomatic, or finally can have advanced liver disease at the time of diagnosis [1–3]. Patients usually present in early stages, and the diagnosis of PBC is most often made when the patient is still asymptomatic with an abnormal cholestatic liver biochemistry and an immunological profile compatible with the disease which is discovered at a routine check [1–3]. Presenting symptoms frequently include fatigue, pruritus, and osteoporosis may be observed initially, in the absence of other signs of liver disease [1–3, 11–13]. The progression of PBC is usually slow paced, but symptoms of portal hypertension and hepatic decompensation (jaundice, ascites, or variceal bleeding) can develop several years after the initial diagnosis [1–3]. The current medical treatment of choice is with ursodeoxycholic acid, which appears to slow the disease progression and greatly improves the quality of life for many patients [14].

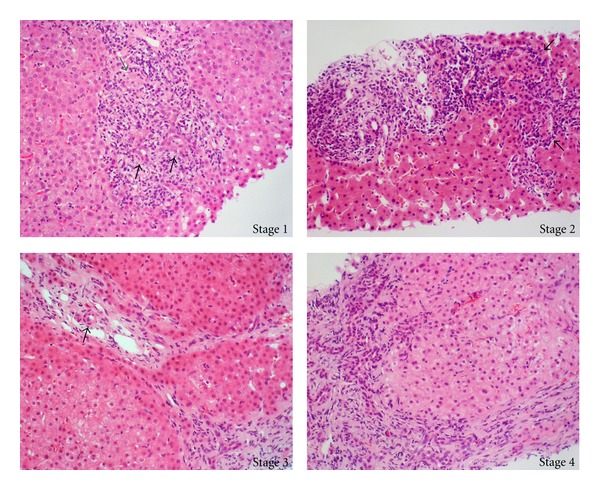

The diagnosis of PBC is based on three widely accepted criteria: biochemical signs of cholestasis, seropositivity for disease-specific autoantibodies, and disease-characteristic histological features (Figure 1) [1–3]. PBC-characteristic histological features include destruction of biliary epithelial cells (BECs) and loss of small bile ducts with portal inflammatory cell infiltration and granuloma formation on occasion [1–3]. Cholestatic markers include increased levels of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and gamma-glutamyl transferase (γGT). IgM may be raised, and the most prominent immunological feature of the disease is the presence of high-titre antibodies against mitochondrial (AMA) and nuclear (ANA) antigens [1–3, 15–24]. AMAs do not appear to have clinical significance; however, disease-specific ANA can identify a subgroup of PBC patients with more advanced disease [15, 16, 24–36]. The presence of ANA at diagnosis seems to be able to identify individuals who will develop advanced disease faster than those seronegative for these autoantibodies [37]. It should be noted that patients may initially be found to be seronegative for AMA or disease-specific ANA with conventional techniques such as that of indirect immunofluorescence (IFL) [20, 38–40]. More sensitive tests using as antigenic source hybrids containing the major mitochondrial antigens have led to the appreciation that “true” AMA-seronegative cases may exist but are fewer than those considered in the past when conventional AMA testing was based on IFL and enzyme immunoassays based on the M2 antigen [20, 38–40].

Figure 1.

Histological staging in a representative case of a patient with primary biliary. Stage 1 reveals duct-centred inflammation showing chronic nonsuppurative destructive cholangitis (black arrows). A tiny granuloma is also seen (grey arrow). Stage 2 shows portal enlargement (arrows) with bile ductular reaction and inflammatory cell infiltration. Stage 3 is characterized by fibrous scaring bridging portal tracts with occasional foci of bile duct loss (no bile duct identified around an artery indicated by arrow). Stage 4 shows cirrhotic transformation.

PBC-specific AMAs are directed against components of the 2-oxo-acid dehydrogenase complexes, especially the E2 subunits of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC-E2), branched-chain 2-oxoacid dehydrogenase complex (BCOADC), and 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex (OGDC) [1, 15, 16, 20, 36]. Anti-PDC-E2 AMAs are present in over 90% of AMA-positive cases [1, 15]. Isotypes of AMA may be IgG, IgA, and IgM, but high-titre AMAs of class IgG are found in up to 95% of patients [1, 15]. It has been demonstrated that the presence of AMA in the general population is much higher than the prevalence of PBC, indicating that AMA may precede the symptomatic onset of the disease [41], and studies have demonstrated that AMA-positive, asymptomatic patients often have histological features diagnostic of, or compatible with, PBC [41–44]. It is therefore considered that seropositivity for AMA is highly predictive of the development of PBC, which indicates the necessity for autoantibody screening and monitoring at regular intervals of close relatives of PBC patients and females in particular [36, 45]. However, the mechanisms responsible for the induction of PBC-specific AMAs and ANAs are not well defined [15, 46–51].

As mentioned, disease-specific ANA may have prognostic significance, which has raised the question as to whether diagnostic testing needs to incorporate assays for PBC-specific ANA [36]. Two ANA patterns may be observed on IFL: the “multiple nuclear dot” pattern mainly targets the nuclear body sp100 and promyelocytic leukaemia (PML) proteins and those giving the “nuclear membrane” (rim-like membranous) recognising gp210, nup62 and other nuclear membrane proteins [16–18, 36]. Both ANA types are present in 30% of PBC patients and can be present in AMA-positive and AMA-negative asymptomatic individuals and also in family members of PBC patients [16–18].

Genetic, epigenetic, environmental, and infectious factors have been considered important for the development of PBC and/or its progression from early stages to more advanced, life-threatening biliary epithelial cell destruction [33, 39, 47, 48, 53–73]. T cell dysregulation also appears to be a feature of PBC [74–79]. Molecular mimicry and immunological cross-reactivity involving homologous microbial and self-antigens have been considered as mechanisms responsible for the induction of disease-specific autoreactivity [33, 36, 50, 51, 58, 59, 80–93]. Genetic and environmental factors are likely involved, as indicated in twin and familial studies [53, 94–97]. Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have allowed for the identification of genetic associations for PBC [39, 66, 67, 98–102]. In vitro studies have implicated antigen-specific B-, CD4, CD8 T-lymphocyte responses in the induction and/or maintenance of autoaggressive pathology [44, 47, 48, 61, 88, 89, 103].

Both the innate and the adaptive arms of the immune system have been considered important for the loss of immunological tolerance to AMA-specific PDC-E2 targets and the subsequent development of the disease [104–112]. As AMAs appear long before disease onset, investigators thought that antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity or antibody-antigen complement activation cell lysis mechanisms may lead to cholangiopathy. The ability of AMAs to inhibit the catalytic activity of PDC-E2 in vitro has further supported the pathophysiological role of AMAs [113]. PDC-E2 complexed with anti-PDC-E2 antibodies generate PDC-E2-specific cytotoxic cells, at a 100-fold lower concentration compared to the PDC-E2 alone [108, 109]. More recent studies have demonstrated the presence of immunologically intact PDC-E2 and other PBC-specific antigens in the surface of human intrahepatic biliary epithelial cell apoptotic bodies, making these antigens susceptible to antibody recognition, a feature which may also promote autoaggression [110–112]. The contribution of the innate and adaptive immune response in the development of PBC has been indicated in animal models resembling human PBC-specific immunopathology [47, 63, 65].

As mentioned, PBC is a disease which predominantly affects females, with the female-to-male ratios ranging from 9 : 1 to 22 : 1 [114, 115]. As such, few studies have taken into account PBC in men from both a pathogenic, as well as clinical viewpoint. The vast majority of PBC studies have been conducted on female patients. This review will examine the literature surrounding PBC in men, from a clinical and experimental standpoint (Table 1). We will also review the current literature which may, in part, explain why PBC rarely affects men and predominantly affects women.

Table 1.

Features of primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) in men and women. Although PBC in men and women is largely similar, certain clinical features such as symptomatology and concomitant diseases differ between the sexes. Very little difference is noted in regards to histological or biochemical features, as well as antimitochondrial antibody (AMA) reactivity.

| Feature | Comment |

|---|---|

| Age | (i) Men older than women |

|

| |

| Histopathology | (i) Largely no difference observed (ii) More stage I in women than in men in one study (iii) One study notes more piecemeal necrosis and pseudoxanthomatous transformation in symptomatic females, and more stainable copper storage in symptomatic males |

|

| |

| Symptomatology | (i) Abdominal pain, constitutional symptoms, and pruritus as a single symptom more common in females (ii) Jaundice as a single symptom more common in males |

|

| |

| Biochemistry | (i) Slightly increased ALP in males versus females in one study; higher γ-GT and ALT in men than in women in another |

|

| |

| Concomitant autoimmune or other diseases | (i) More females experienced Sicca symptoms, scleroderma, and Raynauds (ii) Increased incidence of hepatoma in males |

|

| |

| AMA reactivity | (i) Similar antigenic reactivity patterns in males and females among studies |

|

| |

| ANA reactivity | (i) Anticentromere antibodies more prevalent in women than in men in one study |

1.1. PBC in Males: Case Reports and Epidemiological Studies

PBC occurring in males is relatively infrequent, which is reflected by the scarcity of studies examining PBC in males which are largely limited to case reports and small studies. The only twin study conducted in PBC consisted only of female pairs [95]. Brown and colleagues report PBC in a set of brothers, although the diagnosis in these early cases is questionable [116]. Tanaka et al. [117] notes two sets of brothers with PBC (one set in Britain and the other in France) in addition to several father-daughter and two brother-sister pairs. Unfortunately, the AMA status and clinical course of these patients are unknown [117]. Another set of brothers with a definitive diagnosis of PBC is followed up by the Barcelona group. Lazaridis and colleagues examined AMA status in 306 first-degree relatives of 350 PBC patients and found that AMA was present in 7.8% of brothers, 3.7% of fathers, and 0% of sons of PBC patients. It was not indicated whether the proband of the AMA-positive male's relatives were male or female [118]. The rarity of these case reports reflects the sporadic occurrence of PBC in males, which has also been demonstrated in epidemiological studies.

The female preponderance of PBC is reflected in several large epidemiological studies, and risk factors indicated in these studies tend to focus on those related to women [119–122]. A recent study by Corpechot and colleagues involved a French cohort of 222 PBC patients and 509 controls, all administered a questionnaire regarding demographic, lifestyle, and health factors [119]. In that study, 11% of the PBC patients were male, as were 15% of the control group. Several risk factors indicated include a history of recurrent urinary tract infection (rUTI), smoking, and family history of PBC, as well as oestrogen deficiency [119]. There were no risk factors indicated which were related to male sex [119]. A study by Prince et al. [122] involved two groups of PBC patients, one consisting of 318 patients from an epidemiological study, and the other group consisted of 2258 patients from a PBC support group [122]. The control group consisted of 2438 matched controls. Among PBC patients from the epidemiological study group, 8% were male, compared to 7% in the support group [122], which are similar rates to those found by another group [121]. Again, no specific risk factors were indentified for males, although it was noted in the study by Prince and colleague [122] that less than 1% of males had a history of hair dye use, compared to over 50% of females, which is of interest given that hair dyes have been implicated as a possible risk factor for PBC development. One of the largest epidemiological studies carried out included 1032 PBC patients from 23 tertiary care centres and 1041 controls, all administered a telephone questionnaire [120]. Among PBC patients, 7% were males compared to 8% of the control group. Again, there were no specific risk factors for males indicated [120]. These epidemiological studies have not identified any risk factors which are overtly male-specific, in contrast to several female-specific risk factors such as oestrogen deficiency. All studies demonstrated smoking and rUTI as risk factors [119–123], although it is unclear what proportion of males had a significant history of smoking or rUTI. As well, a recent study has indicated that rUTI occurs before PBC diagnosis in a large proportion of PBC patients but did not indicate what percentage of males had a history of rUTI [124]. The proportion of males with a history of rUTI warrants further investigation.

It is possible that mechanisms such as molecular mimicry with E. coli and other organisms are involved in both men and women [51, 123]. The development of experimental autoimmune cholangiopathy resembling PBC has been described in a 24-month-old C57BL/6 male mouse, after infection with H. pylori [125]. Liver histology demonstrated nonsuppurative, destructive cholangitis, peribiliary lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, and bridging fibrosis [125]. Serum antivacuolating toxin IgG levels were elevated in this mouse, compared to 13 other mice infected with H. pylori [125]. Those authors suggested that PBC may have developed due to molecular mimicry via anti-VacA antibodies [125]. However, Koutsoumpas and colleagues [126] highlighted that Goo et al. [125] did not specify if anti-PDC-E2 (AMAs) were present in the mouse. Further studies demonstrated insignificant homologous regions between H. pylori and PDC-E2 [126]. Inhibition studies abolished reactivity to PDC-E2 but not to VacA, and reciprocal studies using anti-VacA did not inhibit anti-PDC-E2 reactivity [126]. It was therefore unlikely that H. pylori infection was related to the development of PBC by mechanisms of molecular mimicry.

Exposure to environmental toxins has also not been studied in great detail, although this may be of particular interest in regards to PBC in men, based on occupational exposure. It has been noted that some clusters of PBC patients have higher rates of affected males compared to the general population, and some of these clusters are centred around coal mines and steel working industries, which are predominantly employed by men [68]. These observations may warrant further study as to the occupational exposures of men with PBC.

1.2. Clinical, Biochemical, and Histopathological Differences in Male versus Female PBC

Clinical, biochemical, and histopathological differences in men versus women with PBC have been investigated in several early studies [52, 127, 128] (Table 1). One of these was conducted at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology and involved 30 male and 30 age-matched female PBC patients, all AMA positive, with five of the 30 men being asymptomatic [127]. In addition to histological studies, symptoms and biochemical indices were also compared in each group. It was found that females experienced pruritus as a single symptom more often than males, in addition to experiencing more abdominal pain/discomfort as well as constitutional symptoms (malaise, anorexia, weight loss, fatigue, weight loss) [127]. In contrast, males experienced more jaundice, jaundice with pruritus, and upper gastrointestinal bleeding compared to females [127]. From a biochemical standpoint, ALP was slightly higher in symptomatic males compared to asymptomatic males, with both being higher than females in general [127]. Histologically, the only difference found was that symptomatic female patients had more piecemeal necrosis and that symptomatic males had more stainable copper storage than asymptomatic males [127]. Symptomatic females had more marked pseudoxanthomatous transformation than asymptomatic females [127]. That study concluded that there was little difference in male versus female PBC.

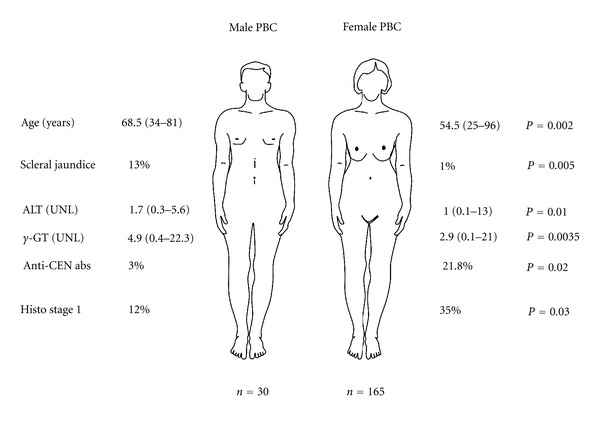

Another study, conducted by a specialist liver unit at King's College Hospital, compared the clinical and biochemical profiles of males and females with PBC, in addition to long-term outcome [128]. Thirty-nine (39) men and 191 women with PBC were enrolled, with the age of diagnosis and disease severity being similar in both groups. Pruritus was found to be less common in males than females (45% versus 68%), and it was suggested that female sex hormones may be linked with pruritus, as there was an increased frequency of women reporting pruritus beginning with the administration of oral contraceptives, as well as during pregnancy [128]. Much like the earlier study [127], the group at King's College Hospital found that gastrointestinal bleeding was more common among males patients (23%) than female patients (15%), although this was not indicated to be statistically significant [128]. In fact, the only statistically significant finding in regards to clinical signs was that females demonstrated skin pigmentation more often than males (55% versus 35%) [128]. Concomitant autoimmune diseases were also examined between the two groups. Sicca symptoms were present in 33% of females and 15% males, scleroderma in 13% of females and 8% of males, and Raynauds in 13% females and 3% of males [128]. These findings suggest that females were more likely to suffer concomitant autoimmune disease than males. Interestingly, that study was the first to report an increased frequency of type 2 diabetes in male PBC patients [128]. As well, men with PBC had a higher frequency of hepatoma, which has also been found in other studies [128–130]. No significant differences were observed in regards to AMA, biochemistry, histology, or survival [128]. An Italian study [52] compared clinical and serological data of 30 consecutive male and 165 female PBC patients (Figure 2). Histology was available in 83% of the males and 79% of females. Clinically, there was a significant difference in age between the two groups, with males presenting at a median age of 68.5 years compared to 54.5 years in females [52]. Scleral jaundice was more common among males (13%) than females (11%), which was the only statistically significant clinical difference among the two groups (Figure 2). However, it should be noted that 64% of males and 51.5% of females were asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis, although this was not statistically significant [52]. Biochemically, males had higher levels of ALT and γGT [52]. Analysis of biopsy specimens revealed that stage I was present in 35% of females compared to 12% of males, although 36% and 28% of males were in stages III and IV, respectively, compared to 19% of females in both stages [52]. However, this was not found to be statistically significant. Immunological profiles regarding AMA and ANA were not different between the two groups, although a higher frequency of anti-centromere activity was noted in females (21.4%) than in males (3%) [52]. That study concluded that more advanced disease in males was most likely due to delayed diagnosis in this group, in which PBC is not initially suspected [52].

Figure 2.

Clinical and Laboratory differences between women and men with PBC. The figure illustrates the significant differences between the Italian cohorts of men and women with PBC analysed by Muratori et al. [52] Only the parameters that reached statistically significant difference are given. More details are provided within the text; UNL, upper normal level; histo, histological; CEN, centromere; abs, antibodies.

The studies above suggest that although there does not appear to be a significant difference in the biochemical, histological, and immunological profiles of males and females with PBC, symptomatology does appear to be different, with males being more likely to experience potentially life threatening complications such as upper gastrointestinal bleeding and hepatoma. It is not clear whether this is due to the advanced stage that these patients are presented due a delay in reaching a definite diagnosis of PBC.

1.3. Autoantibody Profiles in Men versus Women

Although earlier studies addressed AMA positivity between males and females, none have examined the AMA specificities in men and women. Nalbandian and colleagues [114] conducted a study to determine if there were serological differences between men and women. That study involved 46 men and 42 women, all with high titer AMA [114]. Reactivity patterns were similar in both groups: PDC-E2 (72% males, 76% females), E3BP/Protein X (63% males, 62% females), BCOADC-E2 (41% males, 50% females), and OGDC-E2 (24% males, 17% females) [114]. Testing of the optical densities did not reveal any significant difference, which leads to the conclusion that there was no difference of AMA reactivity between males and females [114].

1.4. X Monosomy

Given the female preponderance of PBC, the role of the X chromosome has been investigated [131, 132]. Links between the X chromosome and immunity have been strengthened by clinical data, such as IPEX and XSCID syndromes which are caused by mutations on Xp11 and Xq13.1, respectively [131]. As well, X chromosome defects are more frequent in women with late-onset autoimmune disease [60, 132–134]. Skewed X inactivation appears to be a feature of several autoimmune diseases which are concomitant with PBC, such as systemic sclerosis [135, 136], autoimmune thyroid disease [137], and Sjogren's syndrome [138], but not in PBC [139].

Selmi also indicates that epigenetic factors, such as X chromosome inactivation, may also be involved in the development of PBC, as well as variable concordance rates of PBC among twins [95]. These theories are of interest, given the increased X chromosome monosomy rate in the peripheral lymphocytes of female patients with PBC [60, 133, 140]. Mitchell et al. [140] analysed 125 variable X chromosome inactivation status genes in peripheral blood mRNA and DNA from MZ discordant and concordant pairs. Consistently downregulated genes included CLIC2 and PIN4 in the twin with PBC, which was not found in the healthy twin or in control subjects [140]. Partial or variable methylation was found in both genes and did not predict transcript levels or X inactivation status [140]. That study demonstrates the complexity of epigenetic factors which must be considered not only in twin studies but also in the comparison of men and women with PBC.

1.5. Immunological Differences in Males and Females

Immunological differences may also explain the variable rates of PBC between men and women [134]. For example, females demonstrate enhanced antibody production and cell-mediated responses following immunization [141], in addition to having an increased CD4 T-cell count [142]. Males show increased inflammatory responses to infectious organisms [143], and sex hormones appear to effect cytokine production, B-cell maturation, homing of lymphocytes, and antigen presentation, which is of interest given the association between hormone replacement therapy and PBC [134]. As well, sex hormones can affect immune cell functioning by binding to steroid receptors [144]. Oestrogen and androgen receptors are expressed on B cells, whereas CD8 T cells, monocytes, neutrophils, and NK cells express oestrogen but not androgen receptors [144]. One study has demonstrated that oestrogen treatment of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from SLE patients increased IgG production, as well as anti-dsDNA autoantibody levels [145, 146]. Testosterone was found to decrease IgG and IgM production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in healthy males and females [147]. Despite these findings, it remains unclear as to what role sex hormones play in the pathogenesis of PBC, as well as the preponderance of PBC in females versus males.

2. Conclusion

The reasons underlying the rarity of PBC in males remain elusive. Studies have failed to demonstrate significant differences in the biochemical, immunological and histological features of PBC in men and women. Clinically, there does appear to be some differences between the sexes, with females tending to present with pruritus more than males, and males are at higher risk of developing gastrointestinal bleeding and hepatoma. The reasons for this are unclear. Risk factors for PBC have been reasonably well defined, although these factors do not demonstrate any male-specific risk factors, such as occupational exposures, which is a point that needs to be addressed. As well, rUTI has been demonstrated as a risk factor in females, but the proportion of male PBC patients with a history of rUTI remains unknown. The role of sex hormones in the pathogenesis of PBC also requires further study, as this may also shed some light on why PBC is so rare in males.

Authors' Contribution

E. I. Rigopoulou and D. P. Bogdanos equally contributed in this paper.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Yoh Zen, King's College Hospital, London, for providing the histological images.

Abbreviations

- ALP:

Alkaline phosphatase

- AMAs:

Antimitochondrial antibodies

- ANAs:

Antinuclear antibodies

- BEC:

Biliary epithelial cell

- E.coli:

Escherichia coli

- H. pylori:

Helicobacter pylori

- PBC:

Primary biliary cirrhosis

- PDC:

Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex

- RA:

Rheumatoid arthritis

- SLE:

Systemic lupus erythematosus

- rUTI:

Recurrent urinary tract infection.

References

- 1.Kaplan MM, Gershwin ME. Primary biliary cirrhosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353(12):1261–1273. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hohenester S, Oude-Elferink RPJ, Beuers U. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Seminars in Immunopathology. 2009;31(3):283–307. doi: 10.1007/s00281-009-0164-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neuberger J. Primary biliary cirrhosis. The Lancet. 1997;350(9081):875–879. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)05419-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smyk DS, Rigopoulou EI, Lleo A, et al. Immunopathogenesis of primary biliary cirrhosis: an old wives' tale. Immunity & Ageing. 2011;8(1):p. 12. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-8-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.James OEW, Bhopal R, Howel D, Gray J, Burt AD, Metcalf JV. Primary biliary cirrhosis once rare, now common in the United Kingdom? Hepatology. 1999;30(2):390–394. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sood S, Gow PJ, Christie JM, Angus PW. Epidemiology of primary biliary cirrhosis in Victoria, Australia: high prevalence in migrant populations. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(2):470–475. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim WR, Lindor KD, Locke GR, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of primary biliary cirrhosis in a U.S. community. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(6):1631–1636. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.20197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peters MG, Di Bisceglie AM, Kowdley KV, et al. Differences between Caucasian, African American, and Hispanic patients with primary biliary cirrhosis in the United States. Hepatology. 2007;46(3):769–775. doi: 10.1002/hep.21759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watson RG, Angus PW, Dewar M, Goss B, Sewell RB, Smallwood RA. Low prevalence of primary biliary cirrhosis in Victoria, Australia. Melbourne Liver Group. Gut. 1995;36(6):927–930. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anand AC, Elias E, Neuberger JM. End-stage primary biliary cirrhosis in a first generation migrant south Asian population. European Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 1996;8(7):663–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guanabens N, Cerda D, Monegal A, et al. Low bone mass and severity of cholestasis affect fracture risk in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(7):2348–2356. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parés A, Guañabens N. Osteoporosis in primary biliary cirrhosis: pathogenesis and treatment. Clinics in Liver Disease. 2008;12(2):407–424. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rigamonti C, Bogdanos DP, Mytilinaiou MG, Smyk DS, Rigopoulou EI, Burroughs AK. Primary biliary cirrhosis associated with systemic sclerosis: diagnostic and clinical challenges. International Journal of Rheumatology. 2011;2011:12 pages. doi: 10.1155/2011/976427. Article ID 976427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pares A, Caballeria L, Rodes J. Excellent long-term survival in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis and biochemical response to ursodeoxycholic Acid. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(3):715–720. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bogdanos DP, Baum H, Vergani D. Antimitochondrial and other autoantibodies. Clinics in Liver Disease. 2003;7(4):759–777. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(03)00104-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bogdanos DP, Invernizzi P, Mackay IR, Vergani D. Autoimmune liver serology: current diagnostic and clinical challenges. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008;14(21):3374–3387. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Courvalin JC, Worman HJ. Nuclear envelope protein autoantibodies in primary biliary cirrhosis. Seminars in Liver Disease. 1997;17(1):79–90. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szostecki C, Guldner HH, Will H. Autoantibodies against ’nuclear dots’ in primary biliary cirrhosis. Seminars in Liver Disease. 1997;17(1):71–78. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu H, Norman GL, Shums Z, et al. PBC Screen: an IgG/IgA dual isotype ELISA detecting multiple mitochondrial and nuclear autoantibodies specific for primary biliary cirrhosis. Journal of Autoimmunity. 2010;35(4):436–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dähnrich C, Pares A, Caballeria L, et al. New ELISA for detecting primary biliary cirrhosis-specific antimitochondrial antibodies. Clinical Chemistry. 2009;55(5):978–985. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.118299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bogdanos DP, Komorowski L. Disease-specific autoantibodies in primary biliary cirrhosis. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2011;412(7-8):502–512. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Granito A, Muratori P, Quarneti C, Pappas G, Cicola R, Muratori L. Antinuclear antibodies as ancillary markers in primary biliary cirrhosis. Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics. 2012;12(1):65–74. doi: 10.1586/erm.11.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muratori P, Granito A, Pappas G, et al. The serological profile of the autoimmune hepatitis/primary biliary cirrhosis overlap syndrome. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2009;104(6):1420–1425. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muratori L, Granito A, Muratori P, Pappas G, Bianchi FB. Antimitochondrial antibodies and other antibodies in primary biliary cirrhosis: diagnostic and prognostic value. Clinics in Liver Disease. 2008;12(2):261–276. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Norstrand MD, Malinchoc M, Lindor KD, et al. Quantitative measurement of autoantibodies to recombinant mitochondrial antigens in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis: relationship of levels of autoantibodies to disease progression. Hepatology. 1997;25(1):6–11. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rigopoulou EI, Bogdanos DP, Liaskos C, et al. Anti-mitochondrial antibody immunofluorescent titres correlate with the number and intensity of immunoblot-detected mitochondrial bands in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2007;380(1-2):118–121. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rigopoulou EI, Davies ET, Bogdanos DP, et al. Antimitochondrial antibodies of immunoglobulin G3 subclass are associated with a more severe disease course in primary biliary cirrhosis. Liver International. 2007;27(9):1226–1231. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rigopoulou EI, Davies ET, Pares A, et al. Prevalence and clinical significance of isotype specific antinuclear antibodies in primary biliary cirrhosis. Gut. 2005;54(4):528–532. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.036558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyachi K, Hankins RW, Matsushima H, et al. Profile and clinical significance of anti-nuclear envelope antibodies found in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis: a multicenter study. Journal of Autoimmunity. 2003;20(3):247–254. doi: 10.1016/s0896-8411(03)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakamura M, Kondo H, Mori T, et al. Anti-gp210 and anti-centromere antibodies are different risk factors for the progression of primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;45(1):118–127. doi: 10.1002/hep.21472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bogdanos DP, Liaskos C, Pares A, et al. Anti-gp210 antibody mirrors disease severity in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;45(6):1583–1584. doi: 10.1002/hep.21678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bogdanos DP, Liaskos C, Rigopoulou EI, Dalekos GN. Anti-mitochondrial antibodies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: revealing the unforeseen. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2006;373(1-2):183–185. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bogdanos DP, Pares A, Rodes J, Vergani D. Primary biliary cirrhosis specific antinuclear antibodies in patients from Spain. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2004;99(4):763–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bogdanos DP, Vergani D, Muratori P, Muratori L, Bianchi FB. Specificity of anti-sp100 antibody for primary biliary cirrhosis. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2004;39(4):405–407. doi: 10.1080/00365520310008412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Invernizzi P, Podda M, Battezzati PM, et al. Autoantibodies against nuclear pore complexes are associated with more active and severe liver disease in primary biliary cirrhosis. Journal of Hepatology. 2001;34(3):366–372. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)00040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bogdanos DP, Dalekos GN. Enzymes as target antigens of liver-specific autoimmunity: the case of cytochromes P450s. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2008;15(22):2285–2292. doi: 10.2174/092986708785747508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wesierska-Gadek J, Penner E, Battezzati PM, et al. Correlation of initial autoantibody profile and clinical outcome in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2006;43(5):1135–1144. doi: 10.1002/hep.21172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oertelt S, Rieger R, Selmi C, et al. A sensitive bead assay for antimitochondrial antibodies: chipping away at AMA-negative primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;45(3):659–665. doi: 10.1002/hep.21583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirschfield GM, Liu X, Han Y, et al. Variants at IRF5-TNPO3, 17q12-21 and MMEL1 are associated with primary biliary cirrhosis. Nature Genetics. 2010;42(8):655–657. doi: 10.1038/ng.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vergani D, Bogdanos DP. Positive markers in AMA-negative PBC. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2003;98(2):241–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Metcalf JV, Mitchison HC, Palmer JM, Jones DE, Bassendine MF, James OFW. Natural history of early primary biliary cirrhosis. The Lancet. 1996;348(9039):1399–1402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)04410-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mitchison HC, Bassendine MF, Hendrick A, et al. Positive antimitochondrial antibody but normal alkaline phosphatase: is this primary biliary cirrhosis? Hepatology. 1986;6(6):1279–1284. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840060609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Metcalf JV, Bhopal RS, Gray J, Howel D, James OFW. Incidence and prevalence of primary biliary cirrhosis in the city of Newcastle upon Tyne, England. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1997;26(4):830–836. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.4.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kisand KE, Kisand KV, Karvonen AL, et al. Antibodies to pyruvate dehydrogenase in primary biliary cirrhosis: correlation with histology. Acta Pathologica, Microbiologica et Immunologica Scandinavica. 1998;106(9):884–892. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1998.tb00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lindor KD, Gershwin ME, Poupon R, Kaplan M, Bergasa NV, Heathcote EJ. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2009;50(1):291–308. doi: 10.1002/hep.22906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gershwin ME, Mackay IR. Primary biliary cirrhosis: paradigm or paradox for autoimmunity. Gastroenterology. 1991;100(3):822–833. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)80033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gershwin ME, Mackay IR. The causes of primary biliary cirrhosis: convenient and inconvenient truths. Hepatology. 2008;47(2):737–745. doi: 10.1002/hep.22042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mackay IR, Whittingham S, Fida S, et al. The peculiar autoimmunity of primary biliary cirrhosis. Immunological Reviews. 2000;174:226–237. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.017410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bogdanos DP, Vergani D. Origin of cross-reactive autoimmunity in primary biliary cirrhosis. Liver International. 2006;26(6):633–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bogdanos DP, Vergani D. Bacteria and primary biliary cirrhosis. Clinical Reviews in Allergy and Immunology. 2009;36(1):30–39. doi: 10.1007/s12016-008-8087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bogdanos DP, Baum H, Vergani D, Burroughs AK. The role of E. coli infection in the pathogenesis of primary biliary cirrhosis. Disease Markers. 2010;29(6):301–311. doi: 10.3233/DMA-2010-0745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muratori P, Granito A, Pappas G, et al. Clinical and serological profile of primary biliary cirrhosis in men. QJM. 2007;100(8):534–535. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcm059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McNally RJQ, Ducker S, James OFW. Are transient environmental agents involved in the cause of primary biliary cirrhosis? Evidence from space-time clustering analysis. Hepatology. 2009;50(4):1169–1174. doi: 10.1002/hep.23139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alvaro D, Invernizzi P, Onori P, et al. Estrogen receptors in cholangiocytes and the progression of primary biliary cirrhosis. Journal of Hepatology. 2004;41(6):905–912. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Amano K, Leung PSC, Rieger R, et al. Chemical xenobiotics and mitochondrial autoantigens in primary biliary cirrhosis: identification of antibodies against a common environmental, cosmetic, and food additive, 2-octynoic acid. Journal of Immunology. 2005;174(9):5874–5883. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Amano K, Leung PSC, Xu Q, et al. Xenobiotic-induced loss of tolerance in rabbits to the mitochondrial autoantigen of primary biliary cirrhosis is reversible. Journal of Immunology. 2004;172(10):6444–6452. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bogdanos D, Pusl T, Rust C, Vergani D, Beuers U. Primary biliary cirrhosis following lactobacillus vaccination for recurrent vaginitis. Journal of Hepatology. 2008;49(3):466–473. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bogdanos DP, Baum H, Okamoto M, et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis is characterized by IgG3 antibodies cross-reactive with the major mitochondrial autoepitope and its lactobacillus mimic. Hepatology. 2005;42(2):458–465. doi: 10.1002/hep.20788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bogdanos DP, Baum H, Sharma UC, et al. Antibodies against homologous microbial caseinolytic proteases P characterise primary biliary cirrhosis. Journal of Hepatology. 2002;36(1):14–21. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00252-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Invernizzi P, Miozzo M, Battezzati PM, et al. Frequency of monosomy X in women with primary biliary cirrhosis. The Lancet. 2004;363(9408):533–535. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15541-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jones DE. Pathogenesis of primary biliary cirrhosis. Gut. 2007;56(11):1615–1624. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.122150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jones DEJ, Donaldson PT. Genetic factors in the pathogenesis of primary biliary cirrhosis. Clinics in Liver Disease. 2003;7(4):841–864. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(03)00095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Selmi C, Gershwin ME. The role of environmental factors in primary biliary cirrhosis. Trends in Immunology. 2009;30(8):415–420. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Selmi C, Invernizzi P, Zuin M, Podda M, Gershwin ME. Genetics and geoepidemiology of primary biliary cirrhosis: following the footprints to disease etiology. Seminars in Liver Disease. 2005;25(3):265–280. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-916319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Selmi C, Invernizzi P, Zuin M, Podda M, Seldin MF, Gershwin ME. Genes and (auto)immunity in primary biliary cirrhosis. Genes and Immunity. 2005;6(7):543–556. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu X, Invernizzi P, Lu Y, et al. Genome-wide meta-analyses identify three loci associated with primary biliary cirrhosis. Nature Genetics. 2010;42(8):658–660. doi: 10.1038/ng.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hirschfield GM, Liu X, Xu C, et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis associated with HLA, IL12A, and IL12RB2 variants. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(24):2544–2555. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smyk D, Mytilinaiou MG, Rigopoulou EI, Bogdanos DP. PBC triggers in water reservoirs, coal mining areas and waste disposal sites: from Newcastle to New York. Disease Markers. 2010;29(6):337–344. doi: 10.3233/DMA-2010-0744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smyk D, Rigopoulou EI, Baum H, Burroughs AK, Vergani D, Bogdanos DP. Autoimmunity and environment: am i at risk? Clinical Reviews in Allergy and Immunology. 2012;42(2):199–212. doi: 10.1007/s12016-011-8259-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Invernizzi P, Selmi C, Gershwin ME. Update on primary biliary cirrhosis. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2010;42(6):401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Invernizzi P, Gershwin ME. The genetic basis of primary biliary cirrhosis: premises, not promises. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(4):1044–1047. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Persani L, Bonomi M, Lleo A, et al. Increased loss of the Y chromosome in peripheral blood cells in male patients with autoimmune thyroiditis. Journal of Autoimmunity. 2012;38(2-3):193–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Smyk DS, Rigopoulou EI, Muratori L, Burroughs AK, Bogdanos DP. Smoking as a risk factor for autoimmune liver disease: what we can learn from primary biliary cirrhosis. Annals of Hepatology. 2012;11(1):7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hirschfield GM, Invernizzi P. Progress in the genetics of primary biliary cirrhosis. Seminars in Liver Disease. 2011;31(2):147–156. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1276644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lan RY, Cheng C, Lian ZX, et al. Liver-targeted and peripheral blood alterations of regulatory T cells in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2006;43(4):729–737. doi: 10.1002/hep.21123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Longhi MS, Ma Y, Bogdanos DP, Cheeseman P, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. Impairment of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cells in autoimmune liver disease. Journal of Hepatology. 2004;41(1):31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Longhi MS, Ma Y, Mitry RR, et al. Effect of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cells on CD8 T-cell function in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Journal of Autoimmunity. 2005;25(1):63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Poupon R, Ping C, Chretien Y, et al. Genetic factors of susceptibility and of severity in primary biliary cirrhosis. Journal of Hepatology. 2008;49(6):1038–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Poupon R, Poupon RE. Retrovirus infection as a trigger for primary biliary cirrhosis? The Lancet. 2004;363(9405):260–261. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bogdanos DP, Baum H, Grasso A, et al. Microbial mimics are major targets of crossreactivity with human pyruvate dehydrogenase in primary biliary cirrhosis. Journal of Hepatology. 2004;40(1):31–39. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00501-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bogdanos DP, Lenzi M, Okamoto M, et al. Multiple viral/self immunological cross-reactivity in liver kidney microsomal antibody positive hepatitis C virus-infected patients is associated with the possession of HLA B51. International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology. 2004;17(1):83–92. doi: 10.1177/039463200401700112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kerkar N, Choudhuri K, Ma Y, et al. Cytochrome P4502D6193-212: a new immunodominant epitope and target of virus/self cross-reactivity in liver kidney microsomal autoantibody type 1-positive liver disease. Journal of Immunology. 2003;170(3):1481–1489. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bogdanos DP, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. Virus, liver and autoimmunity. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2000;32(5):440–446. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(00)80266-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Polymeros D, Bogdanos DP, Day R, Arioli D, Vergani D, Forbes A. Does cross-reactivity between mycobacterium avium paratuberculosis and human intestinal antigens characterize crohn’s disease? Gastroenterology. 2006;131(1):85–96. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wen L, Ma Y, Bogdanos DP, et al. Pédiatrie autoimmune liver diseases: the molecular basis of humoral and cellular immunity. Current Molecular Medicine. 2001;1(3):379–389. doi: 10.2174/1566524013363672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bogdanos DP, Baum H, Gunsar F, et al. Extensive homology between the major immunodominant mitochondrial antigen in primary biliary cirrhosis and Helicobacter pylori does not lead to immunological cross-reactivity. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2004;39(10):981–987. doi: 10.1080/00365520410003236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Muratori L, Bogdanos DP, Muratori P, et al. Susceptibility to thyroid disorders in hepatitis C. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2005;3(6):595–603. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shimoda S, Nakamura M, Shigematsu H, et al. Mimicry peptides of human PDC-E2 163-176 peptide, the immunodominant T- cell epitope of primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2000;31(6):1212–1216. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.8090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shimoda S, Van De Water J, Ansari A, et al. Identification and precursor frequency analysis of a common T cell epitope motif in mitochondrial autoantigens in primary biliary cirrhosis. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1998;102(10):1831–1840. doi: 10.1172/JCI4213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bogdanos DP, Smith H, Ma Y, Baum H, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. A study of molecular mimicry and immunological cross-reactivity between hepatitis B surface antigen and myelin mimics. Clinical and Developmental Immunology. 2005;12(3):217–224. doi: 10.1080/17402520500285247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bogdanos DP, Baum H, Butler P, et al. Association between the primary biliary cirrhosis specific anti-sp100 antibodies and recurrent urinary tract infection. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2003;35(11):801–805. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(03)00466-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Baum H, Bogdanos DP, Vergani D. Antibodies to Clp protease in primary biliary cirrhosis: possible role of a mimicking T-cell epitope. Journal of Hepatology. 2001;34(5):785–787. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vergani D, Longhi MS, Bogdanos DP, Ma Y, Mieli-Vergani G. Autoimmune hepatitis. Seminars in Immunopathology. 2009;31(3):421–435. doi: 10.1007/s00281-009-0170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Abu-Mouch S, Selmi C, Benson GD, et al. Geographic clusters of primary biliary cirrhosis. Clinical and Developmental Immunology. 2003;10(2–4):127–131. doi: 10.1080/10446670310001626526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Selmi C, Mayo MJ, Bach N, et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis in monozygotic and dizygotic twins: genetics, epigenetics, and environment. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(2):485–492. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Smyk D, Cholongitas E, Kriese S, Rigopoulou EI, Bogdanos DP. Primary biliary cirrhosis: family stories. Autoimmune Diseases. 2011;2011:11 pages. doi: 10.4061/2011/189585. Article ID 189585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bogdanos DP, Smyk DS, Rigopoulou EI, et al. Twin studies in autoimmune disease: genetics, gender and environment. Journal of Autoimmunity. 2012;38(2-3):156–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Invernizzi P. Human leukocyte antigen in primary biliary cirrhosis: an old story now reviving. Hepatology. 2011;54(2):714–723. doi: 10.1002/hep.24414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Invernizzi P, Selmi C, Poli F, et al. Human leukocyte antigen polymorphisms in Italian primary biliary cirrhosis: a multicenter study of 664 patients and 1992 healthy controls. Hepatology. 2008;48(6):1906–1912. doi: 10.1002/hep.22567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mells GF, Floyd JA, Morley KI, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 12 new susceptibility loci for primary biliary cirrhosis. Nature genetics. 2011;43(4):329–332. doi: 10.1038/ng.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tanaka A, Invernizzi P, Ohira H, et al. Replicated association of 17q12-21 with susceptibility of primary biliary cirrhosis in a Japanese cohort. Tissue Antigens. 2011;78(1):65–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2011.01684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tanaka A, Ohira H, Kikuchi K, et al. Genetic association of Fc receptor-like 3 polymorphisms with susceptibility to primary biliary cirrhosis: ethnic comparative study in Japanese and Italian patients. Tissue Antigens. 2011;77(3):239–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2010.01600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Shimoda S, Nakamura M, Ishibashi H, Hayashida K, Niho Y. HLA DRB4 0101-restricted immunodominant T cell autoepitope of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex in primary biliary cirrhosis: evidence of molecular mimicry in human autoimmune diseases. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1995;181(5):1835–1845. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.5.1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shimoda S, Harada K, Niiro H, et al. Interaction between Toll-like receptors and natural killer cells in the destruction of bile ducts in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2011;53(4):1270–1281. doi: 10.1002/hep.24194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Harada K, Shimoda S, Ikeda H, et al. Significance of periductal Langerhans cells and biliary epithelial cell-derived macrophage inflammatory protein-3α in the pathogenesis of primary biliary cirrhosis. Liver International. 2011;31(2):245–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Harada K, Shimoda S, Sato Y, Isse K, Ikeda H, Nakanuma Y. Periductal interleukin-17 production in association with biliary innate immunity contributes to the pathogenesis of cholangiopathy in primary biliary cirrhosis. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2009;157(2):261–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03947.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Harada K, Nakanuma Y. Cholangiopathy with respect to biliary innate immunity. International Journal of Hepatology. 2012;2012:10 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/793569. Article ID 793569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kita H, Lian ZX, Van De Water J, et al. Identification of HLA-A2-restricted CD8+ cytotoxic T cell responses in primary biliary cirrhosis: T cell activation is augmented by immune complexes cross-presented by dendritic cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2002;195(1):113–123. doi: 10.1084/jem.20010956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kita H, Matsumura S, He XS, et al. Quantitative and functional analysis of PDC-E2-specific autoreactive cytotoxic T lymphocytes in primary biliary cirrhosis. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2002;109(9):1231–1240. doi: 10.1172/JCI14698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lleo A, Bowlus CL, Yang GX, et al. Biliary apotopes and anti-mitochondrial antibodies activate innate immune responses in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2010;52(3):987–998. doi: 10.1002/hep.23783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lleo A, Selmi C, Invernizzi P, et al. Apotopes and the biliary specificity of primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2009;49(3):871–879. doi: 10.1002/hep.22736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rong G, Zhong R, Lleo A, et al. Epithelial cell specificity and apotope recognition by serum autoantibodies in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2011;54(1):196–203. doi: 10.1002/hep.24355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Van de Water J, Fregeau D, Davis P, et al. Autoantibodies of primary biliary cirrhosis recognize dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase and inhibit enzyme function. Journal of Immunology. 1988;141(7):2321–2324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Nalbandian G, Van De Water J, Gish R, et al. Is there a serological difference between men and women with primary biliary cirrhosis? American Journal of Gastroenterology. 1999;94(9):2482–2486. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Selmi C, Meda F, Kasangian A, et al. Experimental evidence on the immunopathogenesis of primary biliary cirrhosis. Cellular and Molecular Immunology. 2010;7(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2009.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bown R, Clark ML, Doniach D. Primary biliary cirrhosis in brothers. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 1975;51(592):110–115. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.51.592.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Tanaka A, Borchers AT, Ishibashi H, Ansari AA, Keen CL, Gershwin ME. Genetic and familial considerations of primary biliary cirrhosis. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2001;96(1):8–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lazaridis KN, Juran BD, Boe GM, et al. Increased prevalence of antimitochondrial antibodies in first-degree relatives of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46(3):785–792. doi: 10.1002/hep.21749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Corpechot C, Chretien Y, Chazouilleres O, Poupon R. Demographic, lifestyle, medical and familial factors associated with primary biliary cirrhosis. Journal of Hepatology. 2010;53(1):162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Gershwin ME, Selmi C, Worman HJ, et al. Risk factors and comorbidities in primary biliary cirrhosis: a controlled interview-based study of 1032 patients. Hepatology. 2005;42(5):1194–1202. doi: 10.1002/hep.20907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Parikh-Patel A, Gold EB, Worman H, Krivy KE, Gershwin ME. Risk factors for primary biliary cirrhosis in a cohort of patients from the United States. Hepatology. 2001;33(1):16–21. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.21165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Prince MI, Ducker SJ, James OFW. Case-control studies of risk factors for primary biliary cirrhosis in two United Kingdom populations. Gut. 2010;59(4):508–512. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.184218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Smyk DS, Bogdanos DP, Kriese S, Billinis C, Burroughs AK, Rigopoulou EI. Urinary tract infection as a risk factor for autoimmune liver disease: from bench to bedside. Clinical Research in Hepatology and Gastroentrology. 2012;36(2):110–121. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Varyani FK, West J, Card TR. An increased risk of urinary tract infection precedes development of primary biliary cirrhosis. BMC Gastroenterology. 2011;11, article 95 doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-11-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Goo MJ, Ki MR, Lee HR, et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis, similar to that in human beings, in a male C57BL/6 mouse infected with Helicobacter pylori. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2008;20(10):1045–1048. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f5e9db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Koutsoumpas A, Mytilinaiou M, Polymeros D, Dalekos GN, Bogdanos DP. Anti-Helicobacter pylori antibody responses specific for VacA do not trigger primary biliary cirrhosis-specific antimitochondrial antibodies. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2009;21(10):p. 1220. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32831a4807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Rubel LR, Rabin L, Seeff LB, Licht H, Cuccherini BA. Does primary biliary cirrhosis in men differ from primary biliary cirrhosis in women? Hepatology. 1984;4(4):671–677. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840040418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lucey MR, Neuberger JM, Williams R. Primary biliary cirrhosis in men. Gut. 1986;27(11):1373–1376. doi: 10.1136/gut.27.11.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Krasner N, Johnson PJ, Portmann B, Watkinson G, Macsween RN, Williams R. Hepatocellular carcinoma in primary biliary cirrhosis: report of four cases. Gut. 1979;20(3):255–258. doi: 10.1136/gut.20.3.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Melia WM, Johnson PJ, Neuberger J, Zaman S, Portmann BC, Williams R. Hepatocellular carcinoma in primary biliary cirrhosis: detection by alpha-fetoprotein estimation. Gastroenterology. 1984;87(3):660–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Selmi C. The X in sex: how autoimmune diseases revolve around sex chromosomes. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2008;22(5):913–922. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Bianchi I, Lleo A, Gershwin ME, Invernizzi P. The X chromosome and immune associated genes. Journal of Autoimmunity. 2012;38(2-3):187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Invernizzi P, Miozzo M, Selmi C, et al. X chromosome monosomy: a common mechanism for autoimmune diseases. Journal of Immunology. 2005;175(1):575–578. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Lleo A, Battezzati PM, Selmi C, Gershwin ME, Podda M. Is autoimmunity a matter of sex? Autoimmunity Reviews. 2008;7(8):626–630. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Ozbalkan Z, Bagislar S, Kiraz S, et al. Skewed X chromosome inactivation in blood cells of women with scleroderma. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2005;52(5):1564–1570. doi: 10.1002/art.21026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Uz E, Loubiere LS, Gadi VK, et al. Skewed X-chromosome inactivation in scleroderma. Clinical Reviews in Allergy and Immunology. 2008;34(3):352–355. doi: 10.1007/s12016-007-8044-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Brix TH, Knudsen GP, Kristiansen M, Kyvik KO, Orstavik KH, Hegedus L. High frequency of skewed X-chromosome inactivation in females with autoimmune thyroid disease: a possible explanation for the female predisposition to thyroid autoimmunity. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2005;90(11):5949–5953. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Ozcelik T. X chromosome inactivation and female predisposition to autoimmunity. Clinical Reviews in Allergy and Immunology. 2008;34(3):348–351. doi: 10.1007/s12016-007-8051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Miozzo M, Selmi C, Gentilin B, et al. Preferential X chromosome loss but random inactivation characterize primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46(2):456–462. doi: 10.1002/hep.21696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Mitchell MM, Lleo A, Zammataro L, et al. Epigenetic investigation of variably X chromosome inactivated genes in monozygotic female twins discordant for primary biliary cirrhosis. Epigenetics. 2011;6(1):95–102. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.1.13405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Weinstein Y, Ran S, Segal S. Sex-associated differences in the regulation of immune responses controlled by the MHC of the mouse. Journal of Immunology. 1984;132(2):656–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Amadori A, Zamarchi R, De Silvestro G, et al. Genetic control of the CD4/CD8 T-cell ratio in humans. Nature Medicine. 1995;1(12):1279–1283. doi: 10.1038/nm1295-1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Bouman A, Jan Heineman M, Faas MM. Sex hormones and the immune response in humans. Human Reproduction Update. 2005;11(4):411–423. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmi008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Rubtsov AV, Rubtsova K, Kappler JW, Marrack P. Genetic and hormonal factors in female-biased autoimmunity. Autoimmunity Reviews. 2010;9(7):494–498. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Kanda N, Tamaki K. Estrogen enhances immunoglobulin production by human PBMCs. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 1999;103(2):282–288. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70503-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Kanda N, Tsuchida T, Tamaki K. Estrogen enhancement of anti-double-stranded DNA antibody and immunoglobulin G production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1999;42(2):328–337. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199902)42:2<328::AID-ANR16>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Kanda N, Tsuchida T, Tamaki K. Testosterone inhibits immunoglobulin production by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 1996;106(2):410–415. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-842.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]