ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND:

Clinical significance of sex hormone receptors in gallbladder cancer is not yet established. This study was performed to assess the expression pattern of estrogen and progesterone receptors in benign and malignant gallbladder lesions, and to assess their clinicopathological significance.

METHODS:

Tissue samples from resected gallbladder for cholelithiasis (n = 20) and carcinoma gallbladder (n = 25) were evaluated for estrogen and progesterone receptor (ER, PR) expression by automated immunohistochemistry. Their expression was correlated with different clinicopathological parameters.

RESULTS:

ER expression was significantly high (28%, 95% confidence interval [CI], 14–47) in gallbladder cancer than in chronic cholecystitis (0%; P = .012). PR expression did not differ in two groups (benign 40%, 95% CI, 21.8–61.4; malignant 52%, 95% CI, 33.5–69.9). Metaplastic benign lesions had near significant higher expression of PR (71.4%) than nonmetaplastic lesion (15.9%; P = .062). Their expression did not correlate with gender, age, menopausal status, presence of gallstones, tumor differentiation, and tumor stage.

CONCLUSION:

Female sex hormones play an important role in the gallbladder carcinogenesis. ER and PR may not have prognostic value. Presence of ER in ∼1/3 and PR in 1/2 of patients with carcinoma gallbladder suggests the potential role of antihormonal therapy.

Carcinoma gallbladder is one of the most common malignancies of the gastrointestinal tract. Its incidence is quite high in northern India, especially along the gangetic belt.1 Cholelithiasis, especially untreated chronic symptomatic gallstones, is one of the main risk factors of gallbladder cancer. Gallstone disease and gallbladder cancers are more frequently observed in females, especially multiparous females.2,3 Sex hormones have been demonstrated to influence the functioning of normal gallbladder.4 Gallbladder emptying is impaired during the luteal phase of menstrual cycle and pregnancy. The risk of development of gallstone disease is further increased by high parity, young age at menarche, early age at first pregnancy, and prolonged fertility. It is therefore assumed that the gallbladder may be a female sex hormone-responsive organ, and these hormones might be involved in the pathogenesis of gallbladder diseases, both gallstones and gallbladder cancer. This hypothesis is further supported by studies showing the presence of estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) in benign5,6 and malignant7,8 gallbladder lesions. Despite the demonstration of ER and PR in gallbladder, evidence for the expression of these receptors and their clinicopathological significance in carcinoma gallbladder has been contradictory.9

In the present study, we have analyzed the expression of ER and PR by the automated immunohistochemistry (IHC) method in both benign and malignant gallbladder tissues in subjects from northern India, where the incidence of carcinoma gallbladder is one of the highest in the world.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This self-funded study was performed from January 2005 to December 2006, and gallbladder tissues from 45 cases (20 benign and 25 malignant) were evaluated. All available samples of gallbladder carcinoma were evaluated, but limited numbers of benign cases were included depending on the availability of suitable cases for immunohistochemistry (eg intact epithelium), and due to financial constraints. Tissue samples were obtained from the resected specimens of gallbladders after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for symptomatic gallstone disease (benign group) or after radical cholecystectomy for the primary gallbladder carcinoma (malignant group). Resected specimens were immediately fixed in 10% buffered formalin. After grossing, tissues were obtained for processing to prepare paraffin blocks. The processing schedule included dehydration in increasing gradients of alcohol followed by clearing in xylene, and then embedding in paraffin wax. Paraffin blocks were cut into thin sections of 5 μm thickness. Sections were dewaxed and stained with hematoxylin & eosin stain for the histological diagnosis. In the benign group, the histological diagnosis of chronic cholecystitis was confirmed. In malignant cases, after the confirmation of the diagnosis, degree of differentiation of the tumor was noted. Tumor differentiation was classified into well, moderately, and poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma depending on the tumor grading.10 In addition, the presence of other histological variants of carcinoma gallbladder was also noted. Presence of metaplasia, if any, was noted in both groups. In all malignant cases, pathological TNM staging was performed following TNM classification of malignant tumors, 7th edition.10

Paraffin blocks of all 45 cases were subjected to immunostaining for ER and PR. Immunohistochemistry was performed using automated immuno-stainer (BioGenex i6000; BioGenex, Fremont, CA) using BioGenex Super Sensitive Streptavidin Biotin Detection System Kit with Progesterone Receptor Clone PR 88 and Estrogen Receptor Clone ER 88 antibody (BioGenex). Antibody reactivity was observed for the location of receptors in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm, intensity of staining, and the mean percentage of receptor positive cells. Positive and negative controls for both antibodies were also run simultaneously.

Patients' demographics and clinical details, eg menopausal status and presence of associated gallstones, were also noted.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used to analyze the data. Continuous variables were expressed as means (range). Fisher's exact test, chi-square test, and Student's t test were used to compare the two cohorts and to correlate ER and PR expression with different clinical and pathological parameters. A two-sided P value less than .05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Patient and Tumor Characteristics

The study population consisted of 45 cases including 20 cases of chronic calculous cholecystitis (benign group) and 25 cases of carcinoma gallbladder (malignant group) (Tables 1, 2) with 36 females and 9 males. The mean age was 39 years (range 22–57 years) in the benign group and 55 years (range 37–73 years) in the malignant group. Benign group included all the cases of chronic calculous cholecystitis with no case of polyp or adenoma. Intestinal metaplasia was found in 35% (7/20) of cases with chronic cholecystitis. Out of 25 malignant cases, 16 (64%) had associated gallstones. Histopathological diagnosis of the primary gallbladder cancer was confirmed in all cases. Associated intestinal metaplasia was not found in any case in this group. Histological variants of adenocarcinoma included two cases each of papillary, metaplastic, squamous, and mucinous adenocarcinoma, and 1 case of small cell carcinoma.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological profile of patients with benign and malignant gallbladder lesions

| Benign (n = 20) | Malignant (n = 25) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (range) | 39 (22–57) | 55 (37–73) | <0.001 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 5 (25) | 4 (16) | 0.481 |

| Female | 15 (75) | 21 (84) | |

| Menopausal status, n (%) | |||

| Premenopausal | 11 (73) | 5 (23) | 0.006 |

| Postmenopausal | 4 (27) | 16 (77) | |

| Associated gallstones, n (%) | 20 (100) | 16 (64) | 0.002 |

| Associated metaplasia, n (%) | 7 (35) | — | — |

| Tumor differentiation, n (%) | — | ||

| Well | 9 (36) | ||

| Moderate | 10 (40) | ||

| Poor | 6 (24) | ||

| Tumor stage,* n (%) | — | ||

| I | — | ||

| II | 3 (12) | ||

| IIIA | 7 (28) | ||

| IIIB | 12 (48) | ||

| IVA | 3 (12) | ||

| IVB | — | ||

| Estrogen receptor expression, n (%) | 0 | 7 (28, 95% CI 14–47) | 0.012 |

| Progesterone receptor expression, n (%) | 8 (40, 95% CI 21.8–61.4) | 13 (52, 95% CI 33.5–69.9) | 0.308 |

TNM classification of malignant tumors, 7th ed.10

Abbreviation: CI = confidence interval.

Table 2.

Correlation of estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor expression with clinicopathological parameters

| Variable | Total | ER present | P value | PR present | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion | |||||

| Benign | 20 | 0 | .012 | 8 | .308 |

| Malignant | 25 | 7 | 13 | ||

| Gender* | |||||

| Male | 9 | 1 | .386 | 3 | .303 |

| Female | 36 | 6 | 18 | ||

| Age (yr)* | |||||

| <50 | 26 | 2 | .099 | 10 | .161 |

| >50 | 19 | 5 | 11 | ||

| Menopausal status* | |||||

| Premenopausal | 16 | 2 | .298 | 7 | .368 |

| Postmenopausal | 20 | 4 | 11 | ||

| Gallstones* | |||||

| Present | 36 | 6 | .570 | 19 | .101 |

| Absent | 9 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Stage | |||||

| I–IIIA | 10 | 3 | .280 | 4 | .284 |

| IIIB–IVA | 15 | 4 | 9 | ||

| Metaplasia | |||||

| Present | 7 | 0 | 1.00 | 5 | .062 |

| Absent | 13 | 0 | 3 | ||

| Tumor differentiation | |||||

| Well/moderate | 19 | 7 | .105 | 10 | .636 |

| Poor | 6 | 0 | 3 | ||

Benign and malignant groups have been combined for the analysis.

Abbreviations: ER = estrogen receptor; PR = progesterone receptor.

Expression Pattern of Estrogen Receptor

Estrogen receptor expression (Tables 1, 2) was absent in all cases in the benign group, and it was present in 7 cases (28%, 95% confidence interval [CI], 14–47) in the malignant group. This difference was found to be statistically significant (P = .012). In all these positive cases, expression was found to be in the cytoplasm only.

In the malignant group, ER expression was 25% (1/4) in males and 28.5% (6/21) in females, and this difference was not statistically significant (P = .452). All the ER-positive tumors were either well or moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma. None of the histological variants in the malignant group expressed ER.

No significant difference in the expression was found with respect to the age (P = .099), menopausal status (P = .298), presence of gallstones (P = .57), metaplastic changes (P = 1.00) (in benign group), tumor differentiation (P = .105) (well/moderately differentiated vs. poorly differentiated), and stage of cancer (P = .280).

Expression Pattern of Progesterone Receptor

Progesterone receptor expression (Tables 1, 2) was 40% (95% CI, 21.8–61.4; 8/20) in the benign group and 52% (95% CI, 33.5–69.9; 13/25) in the malignant group with no significant difference between the two groups (P = .308). In the benign group, PR expression was 46.6% (7/15) in females and 20% (1/5) in males. In the malignant group, it was 52.3% (11/21) in females and 50% (2/4) in males. Overall, no significant difference in PR expression was observed with reference to the gender in either group (P = .303).

In the benign group, PR expression was high in chronic cholecystitis with metaplasia (71.4%, 5/7) than without metaplasia (15.9%, 2/13). This difference was close to the level of significance (P = .062).

In the malignant group, out of 13 PR positive cases, nuclear positivity was observed in all cases. However, only eight cases (61.5%) showed cytoplasmic positivity. In cases with nuclear positivity, the mean percentage of nuclear PR staining was 56% in well-differentiated, 72% in moderately differentiated, and 95% in poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. Among the histological variants of adenocarcinoma, all showed PR expression (Table 3). Similar to ER expression, no significant difference in PR expression was observed with reference to age (P = .161), presence of gallstones (P = .101), menopausal status (P = .368), tumor differentiation (P = .636), and stage of the cancer (P = .284).

Table 3.

Pathological characteristics of primary gallbladder cancer and progesterone receptor expression

| Tumor differentiation/histological variants | PR positive cases n (%) | Location of PR |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear positivity |

Cytoplasmic positivity (grade) | |||

| Positive | N* | |||

| Differentiation | ||||

| Well-differentiated adenocarcinoma (n = 5) | 2 (40) | 2 | 56% | — |

| Moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma (n = 10) | 4 (40) | 4 | 72% | 3 (weak) |

| Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (n = 3) | 1 (33) | 1 | 95% | 1 (strong) |

| Histological variants | ||||

| Papillary adenocarcinoma (well-differentiated) (n = 2) | 2 (100) | 2 | 63% | 1 (strong) |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma (well-differentiated) (n = 2) | 2 (100) | 2 | 31% | 1 (weak) |

| Metaplastic squamous cell (poorly differentiated) (n = 2) | 1 (50) | 1 | 90% | 1 (strong) |

| Small cell carcinoma (poorly differentiated) (n = 1) | 1 (100) | 1 | 80% | 1 (weak) |

| Total (n = 25) | 13 (52) | 13 (52%) | 8 (32%) | |

Average % of nuclei showing positive PR staining.

Abbreviation: PR = progesterone receptor.

DISCUSSION

Primary carcinoma of the gallbladder is the most common malignant lesion of the biliary tract and fifth most common malignancy of the digestive tract.1,11 Estrogen receptor and PR have been demonstrated in normal gallbladder, and they may play a role in gallbladder function. Acting through ER and PR, sex hormones can alter the gallbladder motility by modulating the affinity of receptors in gallbladder to cholecystokinin octapeptide and carbachol.12 Specifically, the presence of PR in the gallbladder makes it more susceptible to circulating hormones and their effect on its motility.4 Inhibitory effect of progesterone hormone on the gallbladder motility may involve its nongenomic action via multiple signaling pathways,13 including inhibition of L-type calcium channel by cAMP/PKA pathways in the gallbladder smooth muscle.14 Alteration in gallbladder motility in association with other predisposing factors may lead to the development of gallstones and malignancy.

Limited studies have shown the presence of ER and PR expression in both normal gallbladder7 and gallbladder with gallstones.5,6 In benign gallbladder lesions expression of ER has been shown in 3.3% to 42% of cases (Table 4). Yamamoto et al15 have demonstrated 19.4% ER nuclear positivity in cases of cholelithiasis. In addition to cholelithiasis cases, they have also studied other benign lesions, eg, epithelial polyps with ER positivity of 33.3% and adenomas with ER positivity of 53.8%, with an overall ER positivity of 34.6% in benign lesions. Other studies have shown ER positivity in 20%7 and 42%6 in benign gallbladder cases with a significant sex difference (more in females than males). In contrast, our study has shown the absence of ER expression in benign gallbladder lesions (the benign group included cases of gallstones only with no case of gallbladder polyp or adenoma).

Table 4.

Estrogen and progesterone receptors expression in gallbladder lesions: literature review

| Author | Benign |

Malignant |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | ER | PR | N | ER | PR | |

| Ranelleti et al,6 1991 | 50 | 42% (c) | 82% (c) | — | — | — |

| Daignault et al,5 1988 | 42 | — | 60% | — | — | — |

| Baskaran et al,7 2005 | 25 | 20% (c) | 22.2 (c) | 21 | 42.8% (c) | 72.2% (c) |

| Yamamoto et al,15 1990 | 75 | 34.6% (n) | — | 114 | 22.8% (n) | — |

| Nema et al,* 2006 | 30 | 3.3% (n) | 0% (n) | 15 | 26.6 % (n) | 60 % (n) |

| 36.6% (c) | 36.6% (c) | 53.3 % (c) | 86.6% (c) | |||

| Nakamura et al,8 1989 | — | — | — | 21 | 52% (n) | 0% (n) |

| 28.6% (c) | 66.7% (c) | |||||

| Park et al,20 2009 | — | — | — | 30 | α 0% (n) | 0% (n) |

| β 73.3% (n) | ||||||

| Shukla et al,19 2007 | — | — | — | 62 | 0% (n) | 2% (n) |

| Albores Saavendra et al,21 2008 | — | — | — | 7 | 0% | 0% |

| Ko et al,24 1995 | — | — | — | 25 | 12% (n) | — |

| Malik et al,18 1998 | — | — | — | 30 | 60% (c) | — |

| Sumi et al,22 2004 | — | — | — | 26 | β 38—42% (n) | — |

| Ohnami et al,25 1988 | — | — | — | 3 | 33% (n) | — |

| Present study | 20 | 0% | 0% (n) | 25 | 0% (n) | 52% (n) |

| 40% (c) | 28% (c) | 32% (c) | ||||

Personal communication, New Delhi, India, 2006.

Abbreviations: α = α isomer; β = β isomer; (c) = cytoplasmic; ER = estrogen receptor; (n) = nuclear; N = number of cases; PR = progesterone receptor.

In benign gallbladder lesions, expression of PR has ranged from 0% to 82% (Table 4) showing a wide variation in its expression. Ranelleti et al6 studied 50 cases of gallstone disease, and found 82% PR positivity with no significant difference in the expression between males and females (72.2% vs. 86.2%). However, they found that even in the absence of ER, the gallbladders of males expressed PR at levels similar to those observed in females, suggesting that a sex difference exists in the coexpression of ER and PR. We have also found higher, although statistically nonsignificant, PR expression in females as compared to males (46.6% vs. 20%).

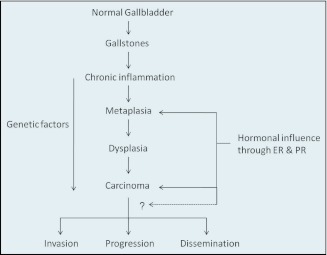

The most accepted model for the development of gallbladder cancer is dysplasia carcinoma sequence. Chronic inflammation causes epithelial regeneration with adaptive changes (eg, metaplasia) with subsequent development of dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, and invasive carcinoma.16 In the present study, metaplasia was found in 35% of cases with chronic calculous cholecystitis. Progesterone receptor expression was seen in higher proportion of cases with metaplasia (71%) than without metaplasia (15%). This difference was close to the level of significance (P = .062). In the literature, PR expression has not been correlated with the presence of metaplasia in gallbladder diseases, although Yamamoto et al15 have shown significantly higher ER expression in metaplastic lesions, both benign and malignant. These observations suggest that possibly PR and ER and their regulating genes may be involved early in the development of gallbladder cancer when the metaplastic changes occur in chronically inflamed gallbladder mucosa, and this step (metaplasia to dysplasia) may be female sex hormones dependent (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Possible role of female sex hormones at various steps in dysplasia carcinoma sequence of gallbladder carcinogenesis.

Role of the sex hormone in the carcinogenesis of gallbladder cancer is still not clear. The development of cancer in gallbladder is a long process and, as stated earlier, follows dysplasia carcinoma sequence. Complex interplay of oxysterol receptor liver X receptor beta (LXR beta), estrogen, and TGF-β may have a crucial role in the malignant transformation of gallbladder epithelium.17 Expression of ER and PR in primary gallbladder carcinoma has been analyzed in very few studies (Table 4). Cytoplasmic positivity of ER has ranged from 28.6%8 to 60%,18 and nuclear positivity has ranged from 0%19 to 73.3%.20 In our study ER expression was 28% (cytoplasmic), similar to as shown by Nakamura et al,8 while nuclear expression was absent in all cases, as in other studies.19–21 We have found significantly higher expression of ER in malignant lesions than in benign lesions (28% vs. 0%). On the contrary, Baskaran et al,7 have shown no such difference. Rather, they found significantly higher expression of PR in malignant lesions (in our study there was no difference). Overexpression of ER in malignant lesions may suggest that female sex hormones, acting through ER, may influence the malignant gallbladder epithelium. Whether it affects the further progression of malignancy, in terms of invasion and dissemination, is not clear at present.

Expression of ER may be related to the differentiation of the tumor. Nakamura et al,8 in 21 patients with gallbladder cancer, found expression of ER more in moderately (50%) to poorly (100%) differentiated tumors than in well-differentiated tumors (44%). Malik et al18 however, found contradictory results with 75% ER expression in well-differentiated tumors as compared to 28% in poorly differentiated tumors. Other studies,15,20,22 including the present one, have also showed that poor differentiation is more likely to be associated with low or absent ER expression. In our study, while 58% (7/12) of well or moderately differentiated tumors expressed ER, it was absent in all poorly differentiated tumors. However, this difference was not statistically significant. Low expression in poorly differentiated tumors indicates that these cells might have escaped the hormonal control leading to altered tumor biology.19 Isoforms of ER, ie ER α and ER β, have also been studied to define their role.20,22 It was found that ER β positivity correlated with tumor differentiation20 and its lack of expression may be associated with more aggressive malignancy.22 We did not study these isoforms separately and did not find any correlation between ER expression and characteristics of aggressive malignancy, ie, poor differentiation or higher tumor stage.

While most of the studies on the role of sex hormones in gallbladder cancer have evaluated ER expression, limited data are available regarding PR expression. In the literature, cytoplasmic PR expression has been observed in 66.7% to 86.6%, while nuclear positivity was found to be absent,8,20,21 low (2%), or high (60%) (Table 4). We have observed 32% cytoplasmic PR positivity and 52% nuclear positivity. In contrast to ER expression, we did not find higher PR expression in malignant tissues as compared to benign lesions. Baskaran et al,7 however, did find significantly higher expression of PR in malignant tissues. It is an interesting observation in all the studies, including the present one, that when both ER and PR expression were evaluated, frequency of PR expression was found to be more than ER expression (Table 4). This may be clinically important in terms of treatment with antihormonal therapy, because PR expression is considered as an indicator of a functionally intact receptor system and more accurate indicator of endocrine responsiveness.23

Similar to ER, association of PR with tumor differentiation is not clear. Nakamura et al8 have found 66.7% expression in well-differentiated, 50% in moderately differentiated, and 100% in poorly differentiated tumors, while in the present study it was 52.6%, 40%, and 75% respectively. Expression rate of PR did not correlate with the tumor differentiation or tumor stage. Although clinical data on survival and tumor recurrence are lacking in the present study, this observation indicates that the expression of ER and PR may not have prognostic significance, although PR has been shown to be associated with better disease stage, longer survival, and better survival within the same stage.7

Literature and the results of the present study suggest wide variation in the incidence of these hormone receptors in gallbladder lesions, both benign and malignant. This variation may be secondary to the ethnic and regional differences, heterogeneity of the patient population, environmental factors, small sample size, and methodology employed to determine the receptor status, ie, manipulation of tissue right from fixation, processing, antigen retrieval, and immunohistochemical staining to the interpretation of the histological findings. Some of the nonsignificant results may be due to lack of power due to small sample size. In addition, there is also the possibility of increased false positive findings due to multiple testing. Given these limitations, these results need to be validated by further studies.

To conclude, significantly higher expression of ER in malignant gallbladder lesions, high expression of PR in benign metaplastic lesions, and high incidence of gallbladder cancer in females despite similar expression of these receptors in males and females suggest that the sex hormones do play an important role in the pathogenesis of gallbladder cancer (Figure 1). This may also explain why gallbladder cancer is more common in females. ER and PR expression may not have prognostic value because they were not found to correlate with the tumor differentiation or tumor stage. Presence of ER in nearly one-third and PR in half of patients with gallbladder cancer in our study suggests that antihormonal therapy might be helpful in this subgroup of patients. Further, expression of these sex hormone receptors is not affected by the age, menopausal status, and presence of gallstones. We need to analyze normal gallbladder tissues, gallbladder with gallstones, benign gallbladder tumors like polyps, and malignant lesions with and without gallstones in larger number of patients to ascertain their role in the carcinogenesis and thus in the treatment of carcinoma gall bladder with antihormonal drugs.

Footnotes

Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dhir V, Mohandas KM: Epidemiology of digestive tract cancers in India IV, gallbladder and pancreas. Indian J Gastroenterol 18:24–28, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen A, Huminer D: The role of estrogen receptors in the development of gallstones and gallbladder cancer. Med Hypotheses 36:259–260, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Singletary BK, Van Thiel DH, Eagon PK: Estrogen and progesterone receptors in human gallbladder. Hepatology 6:574–578, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hould FS, Fried GM, Fazekas AG, Tremblay S, Mersereau WA: Progesterone receptors regulate gallbladder motility. J Surg Res 45:505–512, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Daignault PG, Fazekas AG, Rosenthall L, Fried GM: Relationship between gallbladder contraction and progesterone receptors in patients with gallstones. Am J Surg 155:147–151, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ranelletti FO, Piantelli M, Farinon AM, Zanella E, Capelli A: Estrogen and progesterone receptors in the gallbladders from patients with gallstones. Hepatology 14:608–612, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baskaran V, Vij U, Sahni P, Tandon RK, Nundy S: Do the progesterone receptors have a role to play in gallbladder cancer? Int J Gastrointest Cancer 35:61–68, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nakamura S, Muro H, Suzuki S: Estrogen and progesterone receptors in gallbladder cancer. Jpn J Surg 19:189–194, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barreto SG, Haga H, Shukla PJ: Hormones and gallbladder cancer in women. Indian J Gastroenterol 28:126–130, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C: TNM classification of malignant tumors (ed 7). London, Wiley-Blackwell, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Carriaga MT, Henson DE: Liver, gallbladder, extrahepatic bile ducts, and pancreas. Cancer 75(1 Suppl):171–190, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Messa C, Maselli MA, Cavallini A, et al. : Sex steroid hormone receptors and human gallbladder motility in vitro. Digestion 46:214–219, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kline LW, Karpinski E: Progesterone inhibits gallbladder motility through multiple signaling pathways. Steroids 70:673–679, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wu Z, Shen W: Progesterone inhibits L-type calcium currents in gallbladder smooth muscle cells. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 25:1838–1843, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yamamoto M, Nakajo S, Tahara E: Immunohistochemical analysis of estrogen receptors in human gallbladder. Acta Pathol Jpn 40:14–21, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Roa I, de Aretxabala X, Wistuba I: Histopathology and molecular pathogenesis of gallbladder cancer, in Thomas CR, Fuller CD. (eds): Biliary tract and gallbladder cancer: diagnosis and therapy. New York, Demos Medical Publishing, pp 37–48, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gabbi C, Kim HJ, Barros R, et al. : Estrogen-dependent gallbladder carcinogenesis in LXRbeta−/− female mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:14763–14768, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Malik IA, Abbas Z, Shamsi Z, et al. : Immuno-histochemical analysis of estrogen receptors on the malignant gallbladder tissue. J Pak Med Assoc 48:123–126, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shukla PJ, Barreto SG, Gupta P, et al. : Is there a role for estrogen and progesterone receptors in gall bladder cancer? HPB (Oxford) 9:285–288, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Park JS, Jung WH, Kim JK, et al. : Estrogen receptor alpha, estrogen receptor beta, and progesterone receptor as possible prognostic factor in radically resected gallbladder carcinoma. J Surg Res 152:104–110, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Albores-Saavedra J, Henson DE, Moran-Portela D, Lino-Silva S: Cribriform carcinoma of the gallbladder: a clinicopathologic study of 7 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 32:1694–1698, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sumi K, Matsuyama S, Kitajima Y, Miyazaki K: Loss of estrogen receptor beta expression at cancer front correlates with tumor progression and poor prognosis of gallbladder cancer. Oncol Rep 12:979–984, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McGuire WL, Horwitz KB, Pearson OH, Segaloff A: Current status of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. Cancer 39(Suppl):2934–2947, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ko CY, Schmit P, Cheng L, Thompson JE: Estrogen receptors in gallbladder cancer: detection by an improved immunohistochemical assay. Am Surg 61:930–933, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ohnami S, Nakata H, Nagafuchi Y, Zeze F, Eto S: [Estrogen receptors in human gastric, hepatocellular, and gallbladder carcinomas and normal liver tissues]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 15:2923–2928, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]