Abstract

Management of neuropathic pain in dairy cattle could be achieved by combination therapy of gabapentin, a GABA analog and meloxicam, an NSAID. This study was designed to determine specifically the depletion of these drugs into milk. Six animals received meloxicam at 1 mg/kg and gabapentin at 10 mg/kg while another group (n=6) received meloxicam at 1 mg/kg and gabapentin at 20 mg/kg. Plasma and milk drug concentrations were determined over 7 days post-administration by HPLC/MS followed by non-compartmental pharmacokinetic analyses. The mean (± SD) plasma Cmax and Tmax for meloxicam (2.89 ± 0.48 μg/ml and 11.33 ± 4.12 hours) were not much different from gabapentin at 10 mg/kg (2.87 ± 0.2 μg/ml and 8 hours). The mean (± SD) milk Cmax for meloxicam (0.41 ± 0.16 μg/ml) were comparable to gabapentin at 10 mg/kg (0.63 ± 0.13 μg/ml and 12 ± 6.69 hours). The mean plasma and milk Cmax for gabapentin at 20 mg/kg P.O. were almost double the values at 10 mg/kg. The mean (± SD) milk to plasma ratio for meloxicam (0.14 ± 0.04) was lower than for gabapentin (0.23 ± 0.06). The results of this study suggest that milk from treated cows will have low drug residue concentration soon after plasma drug concentrations have fallen below effective levels.

Keywords: Gabapentin, meloxicam, milk, non-compartmental, dairy cattle, MRL

Introduction

Chronic pain associated with lameness is considered one of the most significant welfare concerns in dairy cows (Whay, Main et al. 2003). Hyperalgesia has been reported to persist in dairy cattle and lame sheep for at least 28 days after the causal lesion has resolved (Ley, Waterman et al. 1996; Whay, Waterman et al. 1998). Inflammatory pain associated with lameness responds modestly to treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (Whay, Main et al. 2003; Flower, Sedlbauer et al. 2008) but neuropathic pain (due to nerve damage or neuronal dysfunction), is considered refractory to the effects of NSAIDs and many opioid analgesics (Woolf and Mannion 1999). Gabapentin (1-(aminomethyl) cyclohexane acetic acid) is a γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) analogue originally developed for the treatment of spastic disorders and epilepsy (Cheng and Chiou 2006). Subsequent studies have established that gabapentin is also effective for the management of chronic pain of inflammatory or neuropathic origin (Hurley, Chatterjea et al. 2002). Although the mechanism of action of gabapentin is poorly understood, it is thought to bind to the α2-δ subunit of voltage gated calcium channels acting pre-synaptically to decrease the release of excitatory neurotransmitters (Taylor 2009).

Gabapentin appears to be absorbed from the gastro-intestinal tract by a saturable amino-acid transporter system (Su et al., 1995). Plasma gabapentin concentrations > 2 μg/mL in humans are associated with a lower frequency of seizures (Sivenius, Kalviainen et al. 1991). Similar doses are used to treat epilepsy and neuropathic pain suggesting that these concentrations will also be effective for analgesia. It has also been reported that gabapentin can interact synergistically with NSAIDs to produce antihyperalgesic effects (Hurley, Chatterjea et al. 2002; Picazo, Castaneda-Hernandez et al. 2006).

Meloxicam is a NSAID of the enolic acid (oxicam) group that is considered to be non-specific cyclooxygenase inhibitor. However, studies from some laboratories show cyclooxygenase-2 selectively at low concentrations in humans (Lazer, Miao et al. 1997), rats (Ogino, Hatanaka et al. 1997), and dogs (Brideau, Van Staden et al. 2001). The plasma pharmacokinetics of meloxicam co-administered with gabapentin has been previously described in cattle (Coetzee, Mosher et al. 2010). Plasma gabapentin concentrations >2 μg/mL were maintained for up to 15 h and meloxicam concentrations >0.2 μg/mL for up to 48 h. The pharmacokinetic profile of oral gabapentin and meloxicam supports clinical evaluation of these compounds for management of neuropathic pain in dairy cattle; however, information regarding the depletion of these compounds in milk is needed to determine when milk from treated animals is safe for human consumption.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Twelve clinically healthy Holstein-Friesian cows, free of mastitis were used in this study as determined by the examination of milk from each animal for gross abnormalities and acceptable level of somatic cell counts, which were in the acceptable range between 13,000 –528,000 cells/mL (The maximum limit allowed is 750,000 per mL according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration-2007 Pasteurized Milk Ordinance). The animals were aged between 34 and 62 months and weighed between 543 and 891 Kg at the time of study. All cows were in their first, second or third lactation. Cows were maintained on a total mixed ration comprising, cottonseed, alfalfa hay, sweet bran and corn silage with ad-libitum water at Kansas State University Dairy Farm.

Animal Phase Study Design

The animals were randomly assigned to two treatment groups comprising 6 animals per group. One group was co-administered gabapentin (400 mg and 100 mg capsules, Actavis Elizabeth LLC, Elizabeth, NJ) and meloxicam (15 mg tablets, Unichem Pharmaceuticals, Rochelle Park, NJ) at a dose of 10 mg/kg and 1 mg/kg respectively. The second group received gabapentin and meloxicam at a dose of 20 mg/kg and 1 mg/kg respectively. The drugs were combined in a gelatin capsule and delivered orally with a balling gun into the oropharynx.

Milk and Blood Sample Collection

Twenty milliliters of milk were collected in polycarbonate bottles from each cow just before drug administration and then every 8 hours coinciding with the milking schedules at the dairy farm for 7 days. The samples were collected from the collection vessel once milking of the cow was completed. The milk from these cows was not added to the bulk tank in order to prevent drug residues from entering the human food chain. The volume of milk produced at each milking by each individual cow was also recorded at the time of sample collection. The samples were immediately brought back to the lab and frozen at −80°C until further analysis.

At each milk sampling time, 10 ml of blood were collected by venipuncture of the jugular vein and transferred to heparinized vacutainers. A set of blood samples was also collected prior to drug administration to confirm that animals did not have previous exposure to the test compounds. Blood samples were immediately brought back to the lab, centrifuged at 1500 g, the plasma transferred to cryovials, and stored at −80°C until further analysis.

Milk Sample Preparation and HPLC/MS analysis

Milk samples were prepared by adding 0.2 mL of the sample or milk standard to 0.1 mL of the internal standard solution containing 1 μg/mL of piroxicam (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA) and 1 μg/mL of pregabalin (Lyrica, Pfizer, Inc., NY, NY, USA). Trichloracetic acid 0.2 mL 30% in water, was added and then the solution was vortexed for 5 seconds. The samples were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 15, 000 × g and then the analytes were extracted from supernatant using solid phase extraction cartridges (SPE, Varian Bond Elute C18, Varian Inc. Palo Alto, CA). The SPE were conditioned with 1 mL methanol followed by 1 mL of water and then 0.35 mL of the sample supernatant was added. The SPE were washed with 1 mL de-ionized water and the analytes eluted with 1 mL methanol. The eluate was evaporated to dryness under an air stream at 40 °C and then reconstituted with 0.2 mL 50% methanol and vortexed for 5 seconds. The solution was centrifuged for 5 minutes at 15,000 × g to sediment particulates and 0.020 mL was injected onto the HPLC. Milk standards were made by adding meloxicam (LKT Laboratories, St. Paul, MN, USA) and gabapentin (Spectrum Chemicals, Gardena, CA, USA) to untreated milk at 0, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, 500, 1000, and 2000 ng/mL each. The linear standard curve was accepted if the predicted values were within 15% of the actual values and the correlation coefficient (R) was at least 0.99. The LOQ of the assay for meloxicam and gabapentin in milk was 10 ng/mL and defined as the lowest concentration of the linear standard curve with a predicted value within 15% of the actual value with an R of at least 0.99. The accuracy was 99 ± 6% of the actual concentration and the coefficient of variation was 6% determined on replicates of 4 each at 10, 100, and 2000 ng/mL for gabapentin in milk. The accuracy was 97 ± 3% of the actual concentration and the coefficient of variation was 2% determined on replicates of 4 each at 10, 100, and 2000 ng/mL for meloxicam in milk.

Plasma Sample Preparation and HPLC/MS Analysis

Plasma samples were prepared by adding 0.05 mL of plasma or plasma standard to 0.2 mL of internal standard solution containing 250 ng/mL of piroxicam and gabapentin in methanol with 0.1% formic acid. The samples were vortexed for 5 seconds and then centrifuged for 10 minutes at 15,000 χ g. The supernatant was transferred to an injection vial with the injection volume being 0.020 mL. Plasma standards were made by adding meloxicam and gabapentin to untreated plasma at 0, 25, 50, 100, 200, 500, 1000, and 5000 ng/mL each. The linear standard curve was accepted if the predicted values were within 15% of the actual values and the correlation coefficient (R) was at least 0.99. The LOQ of the assay for meloxicam and gabapentin in plasma was 25 ng/mL and defined as the lowest concentration of the linear standard curve with a predicted value within 15% of the actual value with an R of at least 0.99. The accuracy was 96 ± 5% of the actual concentration and the coefficient of variation was 5% determined on replicates of 4 each at 10, 100, and 2000 ng/mL for gabapentin in milk. The accuracy was 97 ± 8% of the actual concentration and the coefficient of variation was 7% determined on replicates of 4 each at 50, 500, and 5000 ng/mL for meloxicam in plasma.

The plasma concentrations of gabapentin and meloxicam were simultaneously determined using liquid chromatography (Shimadzu Prominence, Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Columbia, MD, USA) with mass spectrometry (API 2000, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile (mobile phase A) with 0.1% formic acid (mobile phase B) with a constant flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. A mobile phase gradient was used starting at 100% B from 0–1 minutes, a linear gradient to 60% B at 3 minutes which was held until 5 minutes and then a linear gradient to 100% B at 5.5 minutes with a total run time of 8 minutes. A phenyl column (Hypersil Gold, 150×2.1, 5μM, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) maintained at 40 °C achieved separation. The qualifying ion for meloxicam was 352.1 and the quantifying ion for meloxicam was 114.9. The qualifying ion for gabapentin was 172.1 and the quantifying ion for gabapentin was 154.1. The qualifying ion for piroxicam (meloxicam internal standard) was 332.1 and the quantifying ion for piroxicam was 95.1. The qualifying ion for pregabalin (gabapentin internal standard) was 160.0 and the quantifying ion for pregabalin was 142.0. The source temperature was 350 °C and the ionization spray energy was 5000 V. The curtain gas, gas 1, and gas 2 flow rates were 10, 30, and 75 arbitrary units, respectively.

Non-compartmental analysis of plasma and milk time-concentration data

Non-compartmental pharmacokinetic analyses were performed using Excel (Microsoft, WA) add-in program, PK solver (Zhang, Huo et al. 2010) The various parameters estimated included area under the plasma time-concentration curve from time zero to infinity (AUC0−∞), area under the first moment curve from time zero to infinity (AUMC), first-order elimination rate constant (λz), terminal half-life (T1/2 λz), mean residence time (MRT), maximum plasma concentration (Cmax), and time to maximum plasma concentration (Tmax).

Milk excretion analysis

The milk collection times, concentration and production data were fit to an excretion model using Phoenix® WinNonlin™ (Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, CA) to calculate the milk drug excretion rate (MER) over the period using Equation 1.

Where MER is the Milk drug Excretion Rate between subsequent milk collections and represents the amount of drug (ΔA) eliminated in the milk per unit time (Δt), [C] is the milk drug concentration, Ending time is the time of milk collection, and Starting time is the time of collection of the previous milk sample. Other parameters calculated by Phoenix analysis of milk excretion data included: Percentrecovered (cumulative amount of drug eliminated expressed as percentage of administered dose), λz (first order rate constant associated with the terminal portion of the curve), T1/2 λz (terminal half-life), area under the time- milk concentration curve from time zero to infinity (AUC0−∞), maximum plasma concentration (Cmax), and time to maximum plasma concentration (Tmax).

Milk clearance calculation

To determine whether the rate of milk excretion was linearly related to plasma drug concentration, the milk excretion rate (ΔA/Δt) was plotted against the plasma drug concentration at the mid-point between the two sampling times (Cmid, calculated by averaging the plasma drug concentrations that were measured at the current and preceding sampling times). In addition, the slope of the regression line drawn through the points of this graph represents the drugs' milk clearance (CLM/F) (Tucker GT, 1981) and was calculated using Equation 2.

Results

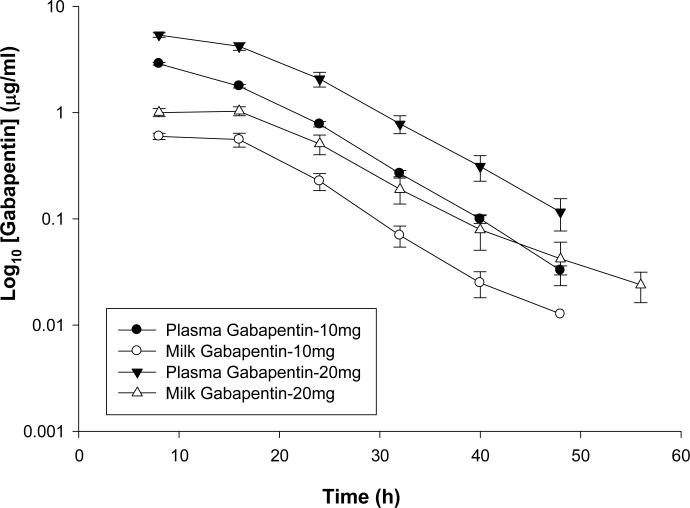

Figure 1 is a plot of the means (± standard error) of both plasma and milk concentration-time profile for gabapentin administered orally at two dose rates of 10 mg/kg and 20 mg/kg. Table 1 is a summary of the non-compartmental pharmacokinetic analysis for gabapentin at 10 mg/Kg and Table 2 is a summary of the non-compartmental pharmacokinetic analysis for gabapentin at 20 mg/Kg dose rates in both milk and plasma. The mean (± SD) plasma Cmax and Tmax for gabapentin administered at 10 mg/kg P.O. were 2.87 ± 0.2 μg/ml and 8.0 ± 0.0 hours respectively while for higher dose (20 mg/kg) the mean (± SD) plasma Cmax and Tmax were 5.42 ± 0.69 μg/ml and 9.33 ± 3.27 hours respectively. On the other hand, the mean (± SD) milk Cmax and Tmax for gabapentin administered at 10 mg/kg P.O. were 0.63 ± 0.13 μg/ml and 12 ± 6.69 hours respectively while for higher dose (20 mg/kg) the 223 mean (± SD) milk Cmax and Tmax were 1.19 ± 0.14 μg/ml and 12 ± 4.4 hours respectively.

Figure 1.

Mean plasma and milk concentrations of Gabapentin following 10 and 20 mg/kg PO administration.

TABLE 1.

Gabapentin Milk and Plasma non-compartmental Pharmacokinetic Parameters following PO Administration at 10 mg/kg

| Parameters | Units | Gabapentin 10 mg/kg (targeted dose) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milk | Plasma | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Mean | STDEV | Min | Max | Median | Mean | STDEV | Min | Max | Median | ||

| λ Z | 1/h | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.014 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.13 |

| t1/2 | h | 4.54 | 0.53 | 3.60 | 4.99 | 4.71 | 5.50 | 0.63 | 4.74 | 6.56 | 5.43 |

| Tmax | h | 12.00 | 6.69 | 8.00 | 24.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 0.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 8.00 |

| Cmax | μg/ml | 0.63 | 0.13 | 0.47 | 0.78 | 0.64 | 2.87 | 0.20 | 2.61 | 3.22 | 2.87 |

| C0 | μg/ml | 0.71 | 0.08 | 0.61 | 0.81 | 0.72 | 4.71 | 0.81 | 3.36 | 5.54 | 4.91 |

| AUC0−t | μg/ml*h | 15.48 | 5.40 | 9.90 | 25.12 | 15.16 | 65.35 | 3.86 | 61.91 | 72.62 | 63.98 |

| AUC0−∞ | μg/ml*h | 15.60 | 5.40 | 10.01 | 25.22 | 15.26 | 65.59 | 3.84 | 62.29 | 72.85 | 64.21 |

| AUMC0−∞ | μg/ml*h2 | 683.14 | 54.60 | 621.66 | 765.53 | 668.82 | |||||

| MRT | h | 10.44 | 0.99 | 9.72 | 12.29 | 9.99 | |||||

| CL/F | mL/h | 156101.41 | 26098.84 | 124358.23 | 183650.18 | 158103.92 | |||||

| CLM/F | mL/h | 300.48 | 57.40 | 225.10 | 358.00 | 308.70 | |||||

| Percentrecovered | % | 0.18 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 0.18 | |||||

| AUC0−t (Milk)/AUC0−t (Plasma) | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.41 | 0.24 | ||||||

TABLE 2.

Gabapentin Milk and Plasma non-compartmental Pharmacokinetic Parameters following PO Administration at 20 mg/kg

| Parameters | Units | Gabapentin 20 mg/kg (targeted dose) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milk | Plasma | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Mean | STDEV | Min | Median | Max | Mean | STDEV | Min | Median | Max | ||

| λ Z | 1/h | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.14 |

| t1/2 | h | 5.20 | 0.77 | 4.08 | 6.10 | 5.20 | 5.26 | 0.57 | 4.79 | 6.03 | 4.99 |

| Tmax | h | 12.00 | 4.40 | 8.00 | 16.00 | 12.00 | 9.33 | 3.27 | 8.00 | 16.00 | 8.00 |

| Cmax | μg/ml | 1.19 | 0.14 | 1.01 | 1.35 | 1.23 | 5.42 | 0.69 | 4.07 | 6.04 | 5.57 |

| C0 | μg/ml | 1.22 | 0.46 | 0.69 | 1.86 | 1.25 | 7.31 | 2.45 | 4.21 | 10.51 | 7.24 |

| AUC0−t | μg/ml*h | 27.56 | 3.12 | 22.29 | 31.36 | 27.28 | 132.00 | 18.25 | 101.08 | 149.73 | 134.42 |

| AUC0−∞ | μg/ml*h | 27.71 | 3.13 | 22.36 | 31.50 | 27.46 | 132.31 | 18.33 | 101.24 | 150.10 | 134.69 |

| AUMC0−∞ | μg/ml*h2 | 1650.27 | 456.98 | 1195.46 | 2273.30 | 1624.75 | |||||

| MRT | h | 12.38 | 2.37 | 9.38 | 15.15 | 13.10 | |||||

| CL/F | mL/h | 150371.87 | 39531.60 | 104942.90 | 145184.25 | 210949.66 | |||||

| CLM | mL/h | 259.57 | 102.82 | 152.50 | 424.10 | 249.65 | |||||

| Percentrecovered | % | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.25 | 0.16 | |||||

| AUC0−t (Milk)/AUC0−t (Plasma) | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.21 | ||||||

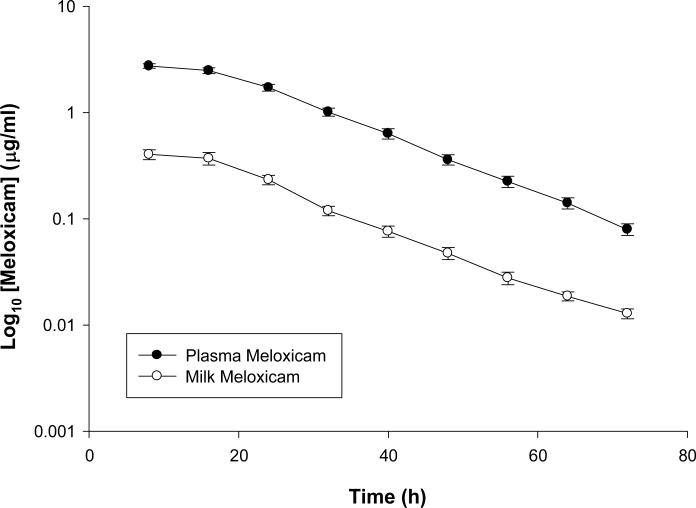

Figure 2 is a plot of the means (± standard error) of both plasma and milk concentration-time profile for meloxicam administered orally at a dose of 1 mg/kg. Table 3 is a summary of various pharmacokinetic parameters in both milk and plasma following non-compartmental analysis for meloxicam. The mean (± SD) plasma Cmax and Tmax for meloxicam (1 mg/kg) were 2.89 ± 0.48 μg/ml and 11.33 ± 4.12 hours respectively while the mean (± SD) milk Cmax and Tmax were 0.41 ± 0.16 μg/ml and 9.33 ± 3.11 hours respectively.

Figure 2.

Mean plasma and milk concentrations of Meloxicam following 1 mg/kg PO administration.

TABLE 3.

Meloxicam Milk and Plasma non-compartmental Pharmacokinetic Parameters following PO Administration at 1mg/kg

| Parameters | Units | Meloxicam 1 mg/kg (targeted dose) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milk | Plasma | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Mean | STDEV | Min | Median | Max | Mean | STDEV | Min | Median | Max | ||

| λ Z | 1/h | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| t1/2 | h | 10.38 | 1.20 | 8.25 | 10.62 | 12.41 | 14.58 | 11.32 | 8.58 | 11.69 | 50.29 |

| Imax | h | 9.33 | 3.11 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 16.00 | 11.33 | 4.12 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 16.00 |

| Cmax | μg/ml | 0.41 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.36 | 0.76 | 2.89 | 0.48 | 2.18 | 2.97 | 3.64 |

| C0 | μg/ml | 0.46 | 0.16 | 0.27 | 0.42 | 0.72 | 3.43 | 1.60 | 2.11 | 2.71 | 7.79 |

| AUC0−t | μg/ml*h | 12.15 | 4.36 | 5.84 | 11.05 | 21.25 | 89.45 | 16.93 | 65.16 | 86.65 | 119.52 |

| AUC0−∞ | μg/ml*h | 12.34 | 4.39 | 5.96 | 11.22 | 21.50 | 89.99 | 16.91 | 65.53 | 87.07 | 119.99 |

| AUMC0−∞ | μg/ml*h2 | 1768.71 | 477.06 | 1016.02 | 1733.20 | 2690.31 | |||||

| MRT | h | 19.46 | 2.54 | 14.18 | 19.60 | 22.42 | |||||

| CL/F | mL/h | 9944.72 | 1961.75 | 6071.01 | 9710.86 | 14092.62 | |||||

| CLM/F | mL/h | 166.52 | 82.15 | 64.10 | 163.10 | 374.20 | |||||

| Percentrecovered | % | 1.61 | 0.76 | 0.97 | 1.44 | 3.69 | |||||

| AUC0−t (Milk)/AUC0−t (Plasma) | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.21 | ||||||

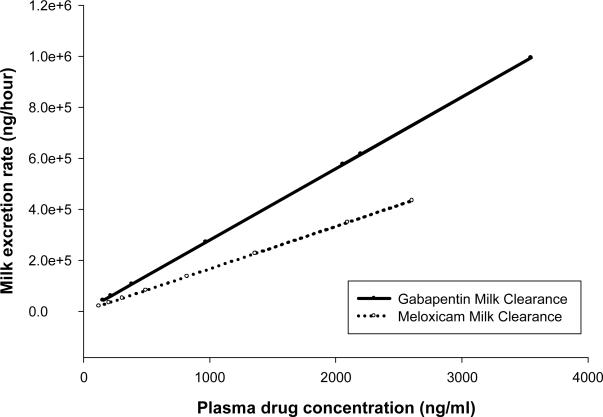

Figure 3 show the calculation of ClM/F for meloxicam and gabapentin by calculating the average slopes of the regression lines drawn through the milk excretion rate versus plasma drug concentration plots. The mean ± SD milk clearance for meloxicam was 166.52 ± 82.15 mL/h while for gabapentin at 10 mg/kg and 20 mg/kg were 300.48 ± 57.4 and 259.57 ± 102.82 mL/h respectively. Since CLM/F was not significantly different between the two gabapentin dose rates, these were combined in Figure 3 to simplify the graph.

Figure 3.

Average slopes of the regression lines drawn through the milk excretion rate versus plasma drug concentration plots for meloxicam and gabapentin, representing the milk clearance of these two drugs.

Milk concentrations depleted below measurable concentrations within 80 hours for meloxicam and 48 and 64 hours for the low and high dose of gabapentin, respectively. Milk to plasma (M/P) ratio was calculated as a measure of the ratio of AUC0−t (milk) over AUC0−t (plasma) to determine the extent of secretion of the given drugs in milk. The mean ± SD M/P ratio for meloxicam was 0.14 ± 0.04 while gabapentin (for combined dose rates) was 0.23 ± 0.06 (Tables 1, 2 and 3). The percentage of meloxicam excreted in milk when given at 1 mg/kg P.O was 1.61 ± 0.76 % while 0.18 ± 0.02 % and 0.17 ± 0.05 % of gabapentin excreted into the milk when given at 10 and 20 mg/kg respectively. The average milk production rate was 980 ± 290 mL/hour.

Discussion

Lactation did not appear to alter the plasma pharmacokinetics of either meloxicam or gabapentin. The pharmacokinetic parameters from this study are comparable to those previously reported for ruminant beef calves (Coetzee, Mosher et al. 2010). Meloxicam and gabapentin crossed from the plasma into the milk following oral administration at clinically relevant doses. For both drugs, milk concentrations depleted to concentrations that were below the level of detection of the analytical technique within approximately 3 days. Milk concentrations that are safe for human consumption have not been established for either of these drugs in the United States, but a maximum residue limit (MRL) has been established in Europe for meloxicam. The level of quantitation of the analytical technique in milk for meloxicam (10 ng/ml) used in this study is lower than the maximum MRL set by the European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products (15 ng/ml) (www.ema.europa.eu).

CLM/F was low (~0.2–0.3 L/h) for both meloxicam and gabapentin when compared to total body clearance (CL/F ~ 10 L/h for meloxicam and ~ 150 L/h for gabapentin) and mammary tissue blood flow in the lactating cow (~120 L/h). This suggests that the mammary gland is inefficient in extracting these drugs from the plasma. Less than 1 and 2% of the administered dose was excreted from the animals' bodies through the milk for gabapentin and meloxicam, respectively.

Two different doses of gabapentin were administered to the animals to determine whether saturable transport across either the gastrointestinal or mammary epithelial barriers at 10 and 20 mg/kg PO would result in non-linear pharmacokinetics. Doubling the dose resulted in a dose-proportional increase in milk and plasma concentrations, whilst the milk clearance remained constant. This suggests that, if the movement of gabapentin across either of these epithelia is facilitated by a transporter, the system was not saturated under the circumstances of this study (doses up to 20 mg/kg PO).

The percentage of the administered gabapentin dose that was excreted through the milk was approximately a tenth lower than for meloxicam. This is despite gabapentin having a higher milk clearance and milk to plasma ratio. The most likely reason for this difference is a lower oral bioavailability for gabapentin. Further studies comparing oral absorption to intravenous pharmacokinetics for this drug would be needed to confirm this hypothesis.

In summary, milk gabapentin and meloxicam concentrations were directly related to plasma concentrations. There was no apparent delay in the appearance of these drugs in the milk, and their rate of depletion from the milk was similar to that from plasma. Neither of the drugs appears to have been sequestered in the mammary tissue or milk. The results of this study suggest that milk from treated cows will have low drug residue concentration soon after plasma drug concentrations have fallen below effective levels. This study further supports the feasibility of using these drugs for the control of pain in food-producing animals, but efficacy studies are needed.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by NIH Grant Number P20RR017686 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health

The authors would also like to thank College of Veterinary Medicine at Kansas State University and Mr. Michael Scheffel of KSU Dairy Unit.

List of Abbreviations

Pharmacokinetic Parameters

- λz

First-order elimination rate constant

- t1/2 λz

Terminal (elimination) half-life

- Tmax

Time to maximum plasma concentration

- Cmax

Maximum plasma concentration

- C0

Initial plasma concentration extrapolated to time zero

- AUC0−t

Area under curve from time zero to time of last measured concentration

- AUC0−∞

Area under curve from time zero to infinity

- AUMC0−∞

Area under the first moment curve from time zero to infinity

- Cl/F

Plasma clearance corrected for unknown bioavailability

- MRT

Mean residence time

Pharmacokinetic Parameters specific for Milk

- CLM/F

Milk Clearance (volume of blood cleared of drug per unit time by passing into the milk) corrected for unknown bioavailability

- Percentrecovered

Cumulative amount of drug eliminated through milk expressed as a percentage of the administered dose

Other Abbreviations

- MER

Milk drug excretion rate

- MRL

Maximum Residue Limit

- M/P

Milk to plasma ratio

- SPE

Solid phase extraction

- LOQ

Limit of quantitation

- GABA

Gamma amino butyric acid

- NSAID

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- SD

Standard deviation

- P.O

Per oral

References

- Brideau C, Van Staden C, et al. In vitro effects of cyclooxygenase inhibitors in whole blood of horses, dogs, and cats. Am J Vet Res. 2001;62(11):1755–60. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2001.62.1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng JK, Chiou LC. Mechanisms of the antinociceptive action of gabapentin. J Pharmacol Sci. 2006;100(5):471–86. doi: 10.1254/jphs.cr0050020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Maximum_Residue_Limits_-_Report/2009/11/WC500014953.pdf.

- Coetzee JF, Mosher RA, et al. Pharmacokinetics of oral 309 gabapentin alone or co-administered with meloxicam in ruminant beef calves. Vet J. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flower FC, Sedlbauer M, et al. Analgesics improve the gait of lame dairy cattle. J Dairy Sci. 2008;91(8):3010–4. doi: 10.3168/jds.2007-0968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley RW, Chatterjea D, et al. Gabapentin and pregabalin can interact synergistically with naproxen to produce antihyperalgesia. Anesthesiology. 2002;97(5):1263–73. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200211000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazer ES, Miao CK, et al. Effect of structural modification of enolcarboxamide-type nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs on COX-2/COX-1 selectivity. J Med Chem. 1997;40(6):980–9. doi: 10.1021/jm9607010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley SJ, Waterman AE, et al. Measurement of mechanical thresholds, plasma cortisol and catecholamines in control and lame cattle: a preliminary study. Res Vet Sci. 1996;61(2):172–3. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5288(96)90096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogino K, Hatanaka K, et al. Evaluation of pharmacological profile of meloxicam as an anti-inflammatory agent, with particular reference to its relative selectivity for cyclooxygenase-2 over cyclooxygenase-1. Pharmacology. 1997;55(1):44–53. doi: 10.1159/000139511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picazo A, Castaneda-Hernandez G, et al. Examination 331 of the interaction between peripheral diclofenac and gabapentin on the 5% formalin test in rats. Life Sci. 2006;79(24):2283–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivenius J, Kalviainen R, et al. Double-blind study of Gabapentin in the treatment of partial seizures. Epilepsia. 1991;32(4):539–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1991.tb04689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su TZ, Lunney E, et al. Transport of gabapentin, a gamma-amino acid drug, by system I alpha-amino acid transporters: a comparative study in astrocytes, synaptosomes, and CHO cells. J Neurochem. 1995;64(5):2125–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64052125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CP. Mechanisms of analgesia by gabapentin and pregabalin--calcium 343 channel alpha2-delta [Cavalpha2-delta] ligands. Pain. 2009;142(1–2):13–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker GT. Measurement of the renal clearance of drugs. Br. J. Clin. Pharmac. 1981;12:761–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1981.tb01304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration Pasturized Milk Ordinance. 2007 http://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodSafety/Product-SpecificInformation/MilkSafety/NationalConferenceonInterstateMilkShipmentsNCIMSMo delDocuments/PasteurizedMilkOrdinance2007/ucm063876.htm.

- Whay HR, Main DC, et al. Assessment of the welfare of 354 dairy cattle using animal-based measurements: direct observations and investigation of farm records. Vet Rec. 2003;153(7):197–202. doi: 10.1136/vr.153.7.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whay HR, Waterman AE, et al. The influence of lesion type on the duration of hyperalgesia associated with hindlimb lameness in dairy cattle. Vet J. 1998;156(1):23–9. doi: 10.1016/s1090-0233(98)80058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf CJ, Mannion RJ. Neuropathic pain: aetiology, symptoms, mechanisms, and management. Lancet. 1999;353(9168):1959–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Huo M, et al. PKSolver: An add-in program for pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data analysis in Microsoft Excel. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2010;99(3):306–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]