Abstract

The very name “psychooncology” implies interaction between brain and body. One of the most intriguing scientific questions for the field is whether or not living better may also mean living longer. Randomized intervention trials examining this question will be reviewed. The majority show a survival advantage for patients randomized to psychologically effective interventions for individuals with a variety of cancers, including breast, melanoma, gastro-intestinal, lymphoma, and lung cancers. Importantly for breast and other cancers, when aggressive anti-tumor treatments are less effective, supportive approaches appear to become more useful. This is highlighted by a recent randomized clinical trial of palliative care for non-small cell lung cancer patients.

There is growing evidence that disruption of circadian rhythms, including rest-activity patterns and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis function, affects cancer risk and progression. Women with metastatic breast cancer have flatter than normal diurnal cortisol patterns, and the degree of loss of daily variation in cortisol predicts earlier mortality. Mechanisms by which abnormal cortisol patterns affect metabolism, gene expression, and immune function are reviewed. The HPA hyperactivity associated with depression can produce elevated levels of cytokines that affect the brain. Tumor cells can, in turn, co-opt certain mediators of inflammation such as NFkB, IL-6, and angiogenic factors to promote metastasis. Also, exposure to elevated levels of norepinephrine triggers release of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) which facilitates tumor growth. Therefore the stress of advancing cancer and management of it is associated with endocrine, immune, and autonomic dysfunction that has consequences for host resistance to cancer progression.

The field of psycho-oncology is hung up on the hyphen in its name. How do we understand the link between mind and body? Is that hyphen merely an arrow to the left, indicating that cancer in the body affects the mind? Can it be an arrow to the right as well, mind affecting the course of cancer? We know that social support affects survival, 1 including that with cancer.2 Also, people tend to die after rather than before their birthdays and major holidays.3,4 Depression worsens survival outcome with cancer.5,6 Yet we have been understandably delicate about mind-body influence, not wanting to claim too much, or to provide unwitting support for overstated claims that wishing away cancer or picturing white blood cells killing cancer cells would actually do it. That arrow to the right is a connection, not a superhighway. Yet in our desire to be respected members of the oncology community we have often minimized a natural ally in the battle against cancer – the patient’s physiological stress coping mechanisms. Even at the end of life, helping patients face death, make informed decisions about level of care, and controlling pain and distress is not only humane but appears to be medically more effective than simply carrying on with intensive anti-cancer treatment alone.7

A recent randomized clinical trial of palliative care for non-small cell lung cancer patients8 makes that case strongly. The authors reported a clear but apparently paradoxical finding: “Despite receiving less aggressive end-of-life care, patients in the palliative care group had significantly longer survival than those in the standard care group (median survival, 11.65 vs. 8.9 months; P=0.02)” (p. 738). Those randomized to palliative care became less depressed as well. The palliative care condition consisted of an average of 4 visits that focused on choices about resuscitation preferences, pain control, and quality of life. The study suggests that at the end of life the most aggressive treatments may not be the most effective, not only psychologically, but also medically.

How could living better at the end of life lead to living longer? When we began to investigate the effects of support groups for people with cancer in the 1970’s, we and others were concerned that watching others die of the same disease would demoralize patients, and might even hasten their death. We evaluated mood and discussion content minute-by-minute to determine whether bad news about other group members was despressogenic. We found that these women with advanced breast cancer talked more seriously about death and dying, but showed no signs of depression or panic.9 Indeed our initial studies, confirmed by many others, indicated that we reduced distress and pain.10,11

But now the results are showing something more profound than reduced distress and pain or feeling better, they are showing that facing death better helps people to live longer with cancer. We reported in 1989 the results of a clinical trial demonstrating that women with metastatic breast cancer randomized to a year of weekly group therapy lived 18 months longer than control patients, and that the difference was not due to differences in initial disease severity or subsequent chemo- and radiotherapy. The result of this 10 year study, cited at last count on Google Scholar 2,222 times, was first greeted with great excitement and later skepticism. Now 21 years later, the findings are being confirmed.

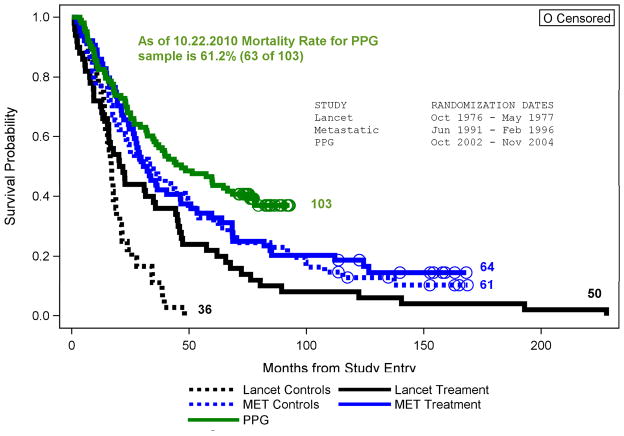

A decade later we conducted an IRB-approved replication study that showed no overall effect of a similar group therapy on breast cancer survival, but a significant interaction with tumor type, such that those with estrogen receptor negative cancers who were randomized to group therapy lived significantly longer than did ER negative patients receiving standard care alone.12 While this is a clear disconfirmation of the hypothesis that facing death together could improve survival, major advances in hormonal and chemotherapies had improved overall survival for women with metastatic breast cancer in the interim.13 However, women with ER negative tumors were largely excluded from the benefit of hormonal treatments, which could account for the difference in findings.13 Further support for this explanation comes from the fact that overall survival of our cohorts of women with metastatic breast cancer has improved over the decades (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of Survival across 3 Spiegel Metastatic Breast Cancer Studies

More recently, a randomized trial of psychoeducational groups for women with primary breast cancer found both significantly reduced rates of relapse and longer survival. 14,15 In addition to this, our original study16, and the recent palliative care study referred to above,8 three other published randomized psychotherapy trials17–20 and one matched cohort trial21 have reported that psychosocial treatment for patients with a variety of cancers enhanced both psychological and survival outcome (See Table 1). However, six other published studies, 22–27 four involving breast cancer patients,24–27 found no survival benefit for those treated with psychotherapy. (See Table 2) Three of these six studies reported no emotional benefit from the interventions,23–25 making enhanced survival unlikely. In another major multicenter replication trial,26 Supportive-Expressive Group Psychotherapy did significantly reduce depression, but did not improve survival. However, the odd thing about this study is that the women randomized to treatment were more depressed to begin with, making their medical prognosis worse at baseline.6 Furthermore, the outcome of all of these studies is not random: no studies show that gathering cancer patients together in groups and directing their attention to emotional expression and mortality shortens survival.28

Table 1.

Randomized Trials Showing Survival Benefit from Psychotherapy

| Study | Cancer | N | Psychological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spiegel et al, 1989 | Metastatic Breast | 86 | Less distress, pain |

| Richardson et al, 1990 | Lymphoma, Leukemia | 94 | Better treatment adherence |

| Fawzy et al, 1993 | Melanoma | 66 | Less distress, better coping |

| Kuchler et al, 1999 | GI cancers | 271 | Better stress management |

| McCorkle et al, 2000 | Solid tumors | 375 | Less distress |

| Spiegel et al., 2007 | Metastatic Breast | 125 | Less distress, pain, survival benefit only among ER negatives |

| Andersen et al, 2010 | Primary breast cancer | 62 | Improved coping |

| Temel et al, 2010 | Non small cell lung cancer | 107 | Improved Q of L, reduced depression |

Table 2.

Randomized Trials Showing No Survival Benefit of Psychotherapy

| Study | Cancer | N | Psychological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linn et al, 1982 | Lung, GI | 120 | Less depression, more self esteem, life satisfaction |

| Ilnyckyj et al, 994 | Breast | 127 | No benefit |

| Cunningham et al, 1998 | Metastatic Breast | 66 | No benefit |

| Edelman et al, 1999 | Metastatic Breast | 121 | No long-term benefit |

| Goodwin et al, 2001 | Metastatic Breast | 235 | Less distress, depression |

| Kissane et al, 2004 | Primary Breast | 303 | Less distress |

| Kissane et al, 2007 | Metastatic Breast | 227 | Prevented new depression, less hopelessness, trauma sx, improved social functioning |

The most provocative but also discordant results have occurred in studies of women with breast cancer, where treatment for ER positive and also human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive (HER2+) tumors has improved substantially. Among cancers with poorer medical prognosis, such as ER negative breast cancer, malignant melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, leukemia, and gastrointestinal cancers, intensive emotional support seems to extend survival. Patients who benefit from a targeted and highly effective chemotherapeutic approach obtain less apparent survival benefit from emotional support than do those with less effective biomedical interventions. Thus, especially in the palliative settling in which aggressive anti-tumor treatments are less efficacious, supportive approaches become more useful. One would think that psychosocial support would have the least biomedical effect in more advanced cancers, and yet our original observation involved women with metastatic breast cancer. By the time someone dies with cancer, they usually have a kilogram of tumor in their body. Yet this may be when the body’s resources for coping with physiological as well as psychological stress matter the most.

Mind/Body Interactions and Cancer Progression

While a large portion of the variance in any disease outcome is accounted for by the specific local pathophysiology of that disease, prognosis must also be explained in part by 'host resistance' factors, which include the manner of response to the stress of the illness29 including the endocrine, neuroimmune, and autonomic nervous systems.30,31 For example, in a series of classic experiments in animals, Riley32,33 showed that crowding accelerated the rate of tumor growth and mortality. In an authoritative review of human stress literature, McEwen34 documents the adverse health effects of cumulative stressors and the body's failure to adapt the stress response to them. Activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) is an adaptive response to acute stress, but over time in response to cumulative stress, the HPA's signal to noise ratio can be degraded, so that it is partially 'on' all the time, leading to adverse physiological consequences, including abnormalities of glucose metabolism35, hippocampal damage,36 accumulation of abdominal fat,37,38 and depression.39,40 Sapolsky and colleagues found that stressed older animals not only had persistently elevated cortisol levels after the stress was over, but also much more rapid growth of implanted tumors.35,41 Abnormalities of HPA function, including glucocorticoid receptor hypersensitivity, have also been found to be associated with post-traumatic stress disorder.42,43 PTSD symptoms, including intrusive preoccupation with the diagnosis, avoidance, and hyperarousal, are common among cancer patients.44–47 Adverse emotional events, ranging from traumatic stressors to cumulative minor ones, are associated with HPA dysregulation. Persistently elevated or relatively invariant levels of cortisol may, in turn, stimulate tumor proliferation35 via differential gluconeogenesis in normal and tumor tissue, activation of hormone receptors in tumor, or immunosuppression.35,48–50 A history of traumatic stress has been found to be associated with shorter disease-free interval and therefore poorer prognosis with breast cancer. 51

Glucocorticoids are potently immunosuppressive, so the effects of acute and chronic stress and related hypercortisolemia may include functional immunosuppression as well. This has been demonstrated clearly in animals52–54 and there is growing evidence in humans as well.55–57 This in turn could influence the rate of breast cancer progression.58–61 Thus glucocorticoid dysregulation may be associated with other stress-related endocrine and immune dysfunction that could adversely affect host resistance to cancer progression.

HPA abnormalities have been demonstrated in cancer patients. Women with metastatic breast cancer have flatter than normal diurnal cortisol patterns62 and flattened diurnal cortisol predicts earlier mortality with breast cancer.63 These aberrant glucocorticoid levels throughout the day may represent a failed response to chronic inflammatory aspects of cancer. For example, chronic inflammatory conditions such as colitis and EBV infection have been associated with colon and naso-pharyngeal cancers respectively.64 Moreover, tumor cells can co-opt certain mediators of inflammation such as NFkB and growth-promoting cytokines and angiogenic factors to promote tumor progression and metastasis. Such chronic inflammation with relatively constant cytokine release into the circulation may trigger a glucocorticoid response that would especially disrupt circadian variation in cortisol levels. This may induce a cycle of glucocorticoid resistance that disrupts negative feedback and glucocorticoid control.65 The pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 is associated with smaller hippocampal volume. Thus there may be an inflammatory cytokine-mediated influence on diurnal cortisol that is associated with breast cancer and its progression. This effect would be worsened by the HPA dysregulation associated with depression, which is also connected to cytokines that trigger ‘sickness behavior’ that overlaps with the symptoms of depression66 and are coupled with HPA axis hyperactivity.67,68 Such dysregulation is also associated with sleep and other circadian system disruption.63 Miller and colleagues have found flattening of diurnal cortisol slope associated with resistance to CRF-DEX suppression, 69 similar to that found among women with metastatic breast cancer.65 IL1 alpha blocks GC receptor translocation in a mouse fibroblast line, reducing the ability of DEX to turn on a reporter gene construct, leading to glucocorticoid resistance.69 This is reversed with administration of an IL-1 receptor antagonist. This pathway demonstrates how cytokines can contribute to the dysregulation of diurnal cortisol seen in women with breast cancer. Thus this provides further evidence that cancer and associated inflammatory processes can dysregulate the HPA axis. The abnormal cortisol patterns, in turn, may affect expression of oncogenes such as BRCA1, and retard apoptosis of malignantly transformed cells. 70 Cytokine-endocrine interactions are plausibly related to depression and adverse cancer outcome via such mechanisms.71

There is also growing evidence that the other major hormonal stress response system in the adrenal gland, the sympathetic-adrenal-system (SAS), also affects cancer progression.72 Epinephrine, produced in the adrenal medulla, is released in the early stress response, increasing heart rate and blood pressure. It also triggers release of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) which stimulates the growth of blood vessels and therefore can provide a blood supply for metastatic cancer cells. This effect is increased by chronic stress in animal models.72 Blocking the effect of norepinephrine with short inhibitory RNAs or beta-blockers reverses this stress-induced increase in VEGF, and reduces tumor growth. Social isolation is associated with higher levels of tumor epinephrine in ovarian cancer patients.73 The most striking clinical application of this relationship are recent studies demonstrating that breast cancer patients who happen to be taking beta adrenergic blockers for hypertension or other problems have longer disease-free and overall survival.74–76

Conclusion

Thus it is plausible that interventions that provide emotional and social support and improve stress management at the end of life might have a positive impact on physiological stress-response systems that affect survival. The line connecting “psycho” social factors to oncology can help to align better stress management and social support with enhanced somatic resistance to tumor growth. Psycho-oncology is a discipline that helps cancer patients mobilize all of their resources to live well with cancer. We know that it is not simply mind over matter, but mind matters.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by NCI grant RO1CA118567

References

- 1.House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241:540–5. doi: 10.1126/science.3399889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reynolds P, Kaplan GA. Social connections and risk for cancer: prospective evidence from the Alameda County Study. Behav Med. 1990;16:101–10. doi: 10.1080/08964289.1990.9934597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phillips DP, Van Voorhees CA, Ruth TE. The birthday: lifeline or deadline? Psychosom Med. 1992;54:532–42. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199209000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phillips DP, Ruth TE, Wagner LM. Psychology and survival [see comments] Lancet. 1993;342:1142–5. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92124-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Penninx BW. Chronically depressed mood and cancer risk in older persons. [see comments.] Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1998;90:1888–93. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.24.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giese-Davis J, Collie K, Rancourt KM, et al. Decrease in depression symptoms is associated with longer survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a secondary analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:413–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spiegel D. Mind matters in cancer survival. JAMA. 2011;305:502–3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spiegel D, Glafkides MC. Effects of group confrontation with death and dying. Int J Group Psychother. 1983;33:433–47. doi: 10.1080/00207284.1983.11491344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spiegel D, Bloom JR, Yalom I. Group support for patients with metastatic cancer. A randomized outcome study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:527–33. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780300039004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spiegel D, Bloom JR. Group therapy and hypnosis reduce metastatic breast carcinoma pain. Psychosom Med. 1983;45:333–9. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198308000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spiegel D, Butler LD, Giese-Davis J, et al. Effects of supportive-expressive group therapy on survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer: a randomized prospective trial. Cancer. 2007;110:1130–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peto R, Boreham J, Clarke M, et al. UK and USA breast cancer deaths down 25% in year 2000 at ages 20–69 years. Lancet. 2000;355:1822. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02277-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersen BL, Yang HC, Farrar WB, et al. Psychologic intervention improves survival for breast cancer patients: a randomized clinical trial. Cancer. 2008;113:3450–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersen BL, Thornton LM, Shapiro CL, et al. Biobehavioral, immune, and health benefits following recurrence for psychological intervention participants. Clin Cancer Res. 16:3270–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spiegel D, Bloom JR, Kraemer HC, et al. Effect of psychosocial treatment on survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Lancet. 1989;2:888–91. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91551-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fawzy F, Fawzy N, Hyun C, et al. Malignant Melanoma: Effects of an early structural psychiatric intervention, coping and affective state on recurrence and survival 6 years later. Arch Gen Psych. 1993;50:681–689. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820210015002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuchler T, Bestmann B, Rappat S, et al. Impact of psychotherapeutic support for patients with gastrointestinal cancer undergoing surgery: 10-year survival results of a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2702–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuchler T, Henne-Bruns D, Rappat S, et al. Impact of Psychotherapeutic Support on Gastrointestinal Cancer Patients Undergoing Surgery: Survival Results of a Trial. Hepato-Gastroenterology. 1999;46:322–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richardson JL, Shelton DR, Krailo M, et al. The effect of compliance with treatment on survival among patients with hematologic malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:356–64. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.2.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCorkle R, Strumpf NE, Nuamah IF, et al. A specialized home care intervention improves survival among older post-surgical cancer patients. [see comments.] Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000;48:1707–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linn MW, Linn BS, Harris R. Effects of counseling for late stage cancer. Cancer. 1982;49:1048–1055. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820301)49:5<1048::aid-cncr2820490534>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ilnyckyj A, Farber J, Cheang M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of psychotherapeutic intervention in cancer patients. Annals of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. 1994;27:93–96. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cunningham AJ, Edmonds CVI, Jenkins GP, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of the Effects of Group Psychological Therapy on Survival in Women with Metastatic Breast Cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 1998;7:508–517. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199811/12)7:6<508::AID-PON376>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edelman S, Lemon J, Bell DR, et al. Effects of group CBT on the survival time of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Psychooncology. 1999;8:474–81. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199911/12)8:6<474::aid-pon427>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodwin PJ, et al. The effect of group psychosocial support on survival in metastatic breast cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345:1719–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kissane DW, Grabsch B, Clarke DM, et al. Supportive-expressive group therapy for women with metastatic breast cancer: survival and psychosocial outcome from a randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2007;16:277–86. doi: 10.1002/pon.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spiegel D. Effects of psychotherapy on cancer survival. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:383–9. doi: 10.1038/nrc800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spiegel D. A 43-year-old woman coping with cancer. [see comments.] JAMA. 1999;282:371–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R. Psychoneuroimmunology and cancer: fact or fiction? European Journal of Cancer. 1999;35:1603–7. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Antonijevic IA. Depressive disorders -- is it time to endorse different pathophysiologies? Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riley V. Mouse mammary tumors: alteration of incidence as apparent function of stress. Science. 1975;189:465–7. doi: 10.1126/science.168638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riley V. Psychoneuroendocrine influences on immunocompetence and neoplasia. Science. 1981;212:1100–9. doi: 10.1126/science.7233204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:171–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801153380307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sapolsky RM, Donnelly TM. Vulnerability to stress-induced tumor growth increases with age in rats: role of glucocorticoids. Endocrinology. 1985;117:662–6. doi: 10.1210/endo-117-2-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sapolsky R, Krey L, McEwen BS. Prolonged glucocorticoidexposure reduces hippocampal neuron number: implication for aging. J Neurosci. 1985;5:1222–1227. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-05-01222.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jayo JM, Shively CA, Kaplan JR, et al. Effects of exercise and stress on body fat distribution in male cynomolgus monkeys. International Journal of Obesity & Related Metabolic Disorders. 1993;17:597–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Epel E, McEwen B, Seeman T, et al. Psychological stress and lack of cortisol habituation among women with abdominal fat distribution. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1999;61:107. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Plotsky PM, Owens MJ, Nemeroff CB. Psychoneuroendocrinology of depression. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1998;21:293–307. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Posener JA, Schildkraut JJ, Samson JA, et al. Diurnal variation of plasma cortisol and homovanillic acid in healthy subjects. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1996;21:33–8. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(95)00033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sapolsky RM, Krey LC, McEwen BS. The adrenocortical stress-response in the aged male rat: impairment of recovery from stress. Exp Gerontol. 1983;18:55–64. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(83)90051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yehuda R, Southwick SM, Krystal JH, et al. Enhanced suppression of cortisol following dexamethasone administration in posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:83–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yehuda R, Teicher MH, Trestman RL, et al. Cortisol regulation in posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression: a chronobiological analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;40:79–88. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00451-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alter CL, Pelcovitz D, Axelrod A, et al. Identification of PTSD in cancer survivors. Psychometrics. 1996;37:137–143. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(96)71580-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malt UF, Tjemsland L. PTSD in women with breast cancer. Psychosomatics. 1999;40:89. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3182(99)71279-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andrykowski MA, Cordova MJ, McGrath PC, et al. Stability and change in posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms following breast cancer treatment: a 1-year follow-up. Psychooncology. 2000;9:69–78. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(200001/02)9:1<69::aid-pon439>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cordova MJ, Andrykowski MA, Kenady DE, et al. Frequency and correlates of posttraumatic-stress-disorder-like symptoms after treatment for breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:981–6. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.6.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ben-Eliyahu S, Yirmiya R, Liebeskind JC, et al. Stress increases metastatic spread of a mammary tumor in rats: evidence for mediation by the immune system. Brain Behav Immun. 1991;5:193–205. doi: 10.1016/0889-1591(91)90016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spiegel D. Psychological distress and disease course for women with breast cancer: One answer, many questions. Jouranl of the National Cancer Institute. 1996;88:629–31. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.10.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spiegel D. Healing words: emotional expression and disease outcome [editorial; comment] Jama. 1999;281:1328–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.14.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Palesh O, Butler LD, Koopman C, et al. Stress history and breast cancer recurrence. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63:233–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sheridan JF, Dobbs C, Jung J, et al. Stress-induced neuroendocrine modulation of viral pathogenesis and immunity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;840:803–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09618.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sheridan JF. Stress-induced modulation of anti-viral immunity -- Normal Cousins Memorial Lecture 1997. Brain, Behav, Immun. 1998;12:1–6. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1998.0521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Padgett DA, Loria RM, Sheridan JF. Endocrine regulation of the immune response to influenza virus infection with a metabolite of DHEA-androstenediol. J Neuroimmunol. 1997;78:203–11. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress-associated immune modulation: relevance to viral infections and chronic fatigue syndrome. American Journal of Medicine. 1998;105:35S–42S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Cacioppo JT, et al. Marital stress: immunologic, neuroendocrine, and autonomic correlates. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;840:656–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cohen S, Tyrrell DA, Smith AP. Psychological stress and susceptibility to the common cold [see comments] N Engl J Med. 1991;325:606–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108293250903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baltrusch HJ, Stangel W, Titze I. Stress, cancer and immunity. New developments in biopsychosocial and psychoneuroimmunologic research. Acta Neurol (Napoli) 1991;13:315–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Levy SM, Herberman RB, Maluish AM, et al. Prognostic risk assessment in primary breast cancer by behavioral and immunological parameters. Health Psychol. 1985;4:99–113. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.4.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Head JF, Elliott RL, McCoy JL. Evaluation of lymphocyte immunity in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1993;26:77–88. doi: 10.1007/BF00682702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Andersen BL, Farrar WB, Golden-Kreutz D, et al. Stress and immune responses after surgical treatment for regional breast cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1998;90:30–36. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.1.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abercrombie HC, Giese-Davis J, Sephton S, et al. Flattened cortisol rhythms in metastatic breast cancer patients. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:1082–92. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sephton SE, Sapolsky RM, Kraemer HC, et al. Diurnal cortisol rhythm as a predictor of breast cancer survival. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92:994–1000. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.12.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lu H, Ouyang W, Huang C. Inflammation, a key event in cancer development. Mol Cancer Res. 2006;4:221–33. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Spiegel D, Giese-Davis J, Taylor CB, et al. Stress sensitivity in metastatic breast cancer: analysis of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:1231–44. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yirmiya R, Pollak Y, Morag M, et al. Illness, cytokines, and depression. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;917:478–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maes M, Bosmans E, Meltzer HY. Immunoendocrine aspects of major depression. Relationships between plasma interleukin-6 and soluble interleukin-2 receptor, prolactin and cortisol. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1995;245:172–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02193091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Maes M. Major depression and activation of the inflammatory response system. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;461:25–46. doi: 10.1007/978-0-585-37970-8_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Raison CL, Borisov AS, Woolwine BJ, et al. Interferon-alpha effects on diurnal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity: relationship with proinflammatory cytokines and behavior. Mol Psychiatry. 2008 doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Antonova L, Mueller CR. Hydrocortisone down-regulates the tumor suppressor gene BRCA1 in mammary cells: a possible molecular link between stress and breast cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2008;47:341–52. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Raison CL, Miller AH. Depression in cancer: new developments regarding diagnosis and treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:283–94. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00413-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sood AK, Lutgendorf SK. Stress influences on anoikis. Cancer prevention research. 2011;4:481–5. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lutgendorf SK, DeGeest K, Dahmoush L, et al. Social isolation is associated with elevated tumor norepinephrine in ovarian carcinoma patients. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:250–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Barron TI, Connolly RM, Sharp L, et al. Beta blockers and breast cancer mortality: a population- based study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:2635–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.5422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Melhem-Bertrandt A, Chavez-Macgregor M, Lei X, et al. Beta-blocker use is associated with improved relapse-free survival in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:2645–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.4441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Powe DG, Voss MJ, Zanker KS, et al. Beta-blocker drug therapy reduces secondary cancer formation in breast cancer and improves cancer specific survival. Oncotarget. 2010;1:628–38. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]