Abstract

Denileukin Diftitox (DD), a fusion protein comprised of IL-2 and diphtheria toxin was initially expected to enhance anti-tumor immunity by selectively eliminating regulatory T cells (Tregs) displaying the high affinity IL-2R (α-β-γ trimers). While DD has been shown to deplete some Tregs in primates, its effects on NK cells (CD16+CD8+NKG2A+CD3−), which constitutively express the intermediate affinity IL-2R (β-γ dimers) and play a critical role in anti-tumor immunity, are still unknown. To address this question, cynomolgus monkeys were injected intravenously with two different doses of DD (8 or 18 μg/Kg). This treatment resulted in a rapid but short-term reduction in detectable peripheral blood resting Tregs (R-Tregs: CD4+CD45RA+Foxp3+) and a transient increase in the number of activated Tregs (A-Tregs: CD4+CD45RA−Foxp3high) followed by their partial depletion (50–60%). On the other hand, all NK cells were deleted immediately and durably after DD administration. This difference was not due to a higher binding or internalization of DD by NK cells as compared to Tregs. Co-administration of DD with IL-15, which binds to IL-2Rβ-γ, abrogated DD-induced NK cell deletion in vitro and in vivo while it did not affect Tregs elimination. Taken together, these results show that DD exerts a potent cytotoxic effect on NK cells, a phenomenon which might impair its anti-tumoral properties. However, co-administration of IL-15 with DD could alleviate this problem by selectively protecting potentially oncolytic NK cells while allowing the depletion of immunosuppressive regulatory T cells in cancer patients.

Introduction

Denileukin Diftitox (DD) is a fusion protein composed of IL-2 and diphtheria toxin, which has been designed to kill cells expressing the IL-2 receptor (IL-2R). Since regulatory T cells (Tregs) constitutively express all three subunits of the high affinity IL-2R (α, β and γ), DD was expected to bind and deplete preferentially this T cell subset. Based upon this principle, DD has been administered to eliminate presumably immunosuppressive Tregs in cancer patients to enhance anti-tumor immunity (1–5). DD treatment has been tested in patients exhibiting IL-2Rα (CD25) positive cutaneous T cell lymphoma and other cancers including renal cell carcinoma (6), melanoma (7), B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma and lung cancer (8–13). Limited anti-tumoral effects have been observed in these patients, an outcome which has been attributed to incomplete and short-lasting Tregs depletion (4, 14–16). However, an alternative hypothesis, that DD could also delete some effector immune cells and thereby impairs its anti-tumor efficacy, has not been thoroughly investigated.

DD is most toxic to cells expressing the high affinity heterotrimer IL-2R (α, β and γ) with a half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 10−12 M. In contrast, other cells exhibiting the intermediate affinity receptor consisting of β and γ subunits (IL-2Rβ-γ) such as NK cells are more resistant to DD-mediated depletion (IC50: 10−10 M) (8, 17–19). Of note, however, DD is regularly found at serum concentrations of 1–5 × 10−9 M in treated patients, which is ten times higher than that required to reach the IC50 even of cells displaying only IL-2Rβ-γ. This suggests that, in addition to its effect on Tregs, in vivo DD administration could also eliminate some cells expressing the intermediate affinity IL-2R.

In this study, we investigated the effects of DD in vivo and in vitro on the survival and activation of peripheral blood Tregs, effector T cells and natural killer (NK cells) in cynomolgus monkeys. Partial and transient depletion of effector T cells and Tregs was observed. More strikingly, however, DD treatment resulted in complete and long-lasting elimination of NK cells. Interestingly, co-administration of DD with IL-15, which binds selectively to IL-2/15R β subunit, prevented the depletion of NK cells while it did not alter Tregs elimination. The implications of these findings for the design of IL-2R-based immune therapies in cancer are discussed.

Material and Methods

Animals and treatments

5–7 kg male cynomolgus macaques (Charles River Primates, Wilmington, MA) were used. The studies were performed under protocols approved by the National Institute of Health guidelines for the care and use of primates and the Massachusetts General Hospital Subcommittee on Animal Research. Denileukin Diftitox (DD) (Ontak; Eisai, Woodcliff Lake, NJ) was given intravenously at high doses: 18 μg/kg given twice on two consecutive days or 8 μg/kg given four times weekly. In DD-IL-15 co-administration experiments, two different doses (10 or 50 μg/kg) of IL-15 (Insight Genomics, Falls Church, VA) were given to each animal intravenously at the time of each DD infusion.

Flow cytometry analyses

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were analyzed via cell surface staining using monoclonal antibodies directed against the following antigens: CD3 (SP34), CD4 (L200), CD8 (RPA-T8), CD16 (3G8), CD20 (2H7), CD45RA (5H9), CD56 (B159), CD62L (SK11), CD95 (DX-2), NKG2A (Z199), and isotype-matched control mAbs. To assess intracellular protein expression of Foxp3 (PCH101), Ki67 (B56) and CD152 (BNI3), cells were permeabilized using fixation/Permeabilization solution (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) following manufacture’s instruction. Cells were analyzed on a FACS Calibur or Accuri Flowcytometer using Flowjo software.

Cytotoxic and competition assays

PBMCs from either NHPs were cultured for 12–72 hours in complete media (RPMI1640, 10%FCS, 12ml HEPES, 100U/ml penicillin, 100μg/ml streptomycin and 2mM glutamine) with DD (0–5nM) and followed by staining for specific populations.

NK cells were sorted into CD16+CD8+NKG2A+CD3− (20), CD4+ Tregs were sorted into resting Tregs (R-Tregs: CD45RA+CD25++) and activated Tregs (A-Tregs: CD45RA−CD25++) by FACS Aria cell sorter. Each population was cultured in complete media with or without DD in the presence of different concentrations of IL-2 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or IL-15 (R&D, Minneapolis, MN). Cytotoxicity was determined by 7-aminoactinomycin D (BD, San Diego, CA). The viability was analyzed as a percentage relative to the level of pre-incubation.

Binding and Internalization of DD

DD was labeled using the Alexa Fluor 647 protein labeling kit (Invitrogen) following the manufacture’s instruction. Cells were analyzed on a FACS Calibur or Accuri Flowcytometer using Flowjo software. DD internalization analyses were performed by imaging flow cytometry using the ImageStreamX® Imaging Flow Cytometer (Amnis, Seattle, WA). For these analyses, DC nuclei were counterstained with Dapi, and the data were analyzed with IDEAS software Version 4.0 (Amnis). Only live cells were gated. For quantification of internalization, 2 × 106 PBMCs were cultured with Alexa-647-labeled DD (5nM) and cells were analyzed after 3 hours or 6 hours. We used multiple surface markers to identify Tregs (CD45RA-FITC, CD25-PE, CD4-APC-cy7) and NK cells (CD16-FITC, CD8-PE) and identified the internalization of Alexa-647 labeled DD using a quantitative morphology based feature (IDEAS software Version 4.0 from Amnis).

Statistical analyses

Statistical significance was examined with a two-tailed Student t-test, with values of P<0.05 being considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

In vivo effects of DD administration on peripheral blood leukocyte subsets

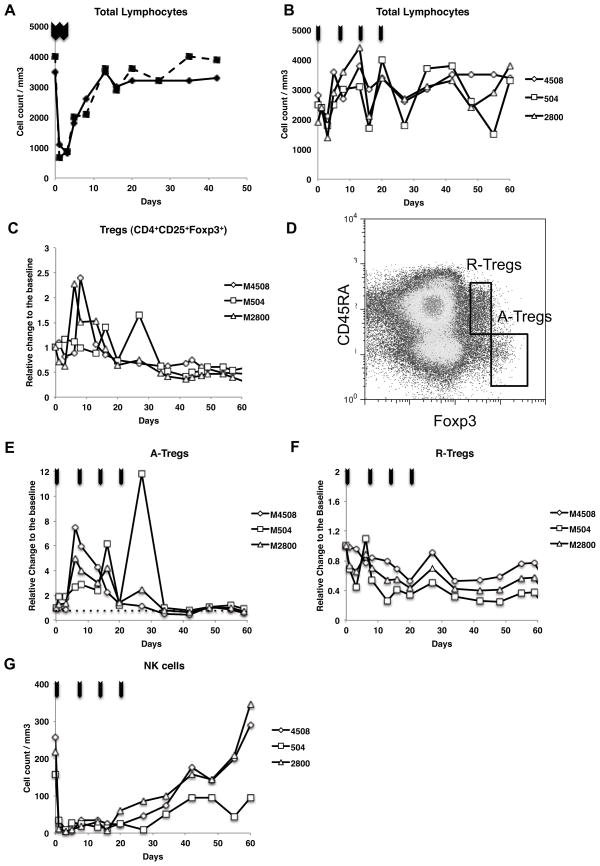

Following intravenous administration of cynomolgus monkeys with high dose (18 μg/kg × 2) DD, the total number of peripheral blood lymphocytes rapidly dropped from 3500/mm3 to 800/mm3 (day2). This effect was transient as the lymphocytes counts started to increase by day 5 and returned to pretreatment levels by day 10 post-DD administration (Fig. 1A). Since this population contains only 2–4% Tregs, we can conclude that this effect reflected largely the elimination of effector T cells (Teffs). Next, we tested a lower multiple-doses administration protocol (8 μg/kg × 4, weekly). Transient reduction of the total lymphocytes counts was again observed, but to a much lesser degree (Fig. 1B). This prompted us to use this regimen in this study aimed at more selective Treg depletion, as previously used in clinical trials (1).

Figure 1. In vivo effects of DD on various peripheral blood lymphocytes in Monkeys.

A: Reduction of total peripheral lymphocytes counts with high dose DD (18 μg/kg × 2). B: With multiple low doses (8 μg/kg × 4, weekly). C: Absolute count of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs slowly decreased to less than 50% of baseline levels over two months following DD treatment. D: Tregs were divided into CD45RA+Foxp3+ (R-Tregs) and CD45RA−Foxp3++ (A-Tregs). E and F: Marked transient expansion of A-Tregs was seen in all three recipients while R-Tregs consistently decreased. G: Sequential low dose DD treatments induced immediate and long-term depletion of NK cells from peripheral circulation. Arrows indicate the administration of DD.

In fact, early selective depletion of Tregs was not observed with the actual frequency of Tregs initially increasing from day 2 to day 10 after DD injection (Fig. 1C). Subsequently, similar to observations reported in humans (1), both the absolute count and the percentage of Foxp3+CD4+ T cells among total CD4+ T cells gradually decreased and remained low for several weeks (< 50%)(Fig. 1C). To more precisely evaluate the in vivo effects of DD on specific cell subpopulations, we applied the phenotypic definition of human Treg subpopulations proposed by Miyara et al. (21) to cynomolgus monkeys. Our preliminary studies showed that monkey Tregs can similarly be separated as activated Tregs (A-Tregs: CD4+CD45RA−Foxp3++) and resting Tregs (R-Tregs: CD4+CD45RA+Foxp3+)(Fig. 1D). Suppressive function of each Treg subpopulation was also similar to human Tregs, where A-Tregs possess significantly higher suppressive function than R-Treg (Data not shown). The current study revealed that the initially increased numbers of peripheral blood Tregs corresponded to A-Tregs (Fig. 1E) exhibiting a phenotype identical to that expressed by human A-Tregs: CD62L−, CD31−, CD152 (CTLA-4)+, Ki-67+ and CD95+ (Supplemental Fig. 1). In contrast, DD treatment resulted in a marked and immediate decrease in frequency of R-Tregs (60–80%), which remained low for two months (Fig. 1F).

The most striking effect observed immediately after initial DD injection was a complete depletion of NK cells (CD16+CD8+NKG2A+CD3−). The frequency of NK cells remained low for 20 days before gradually returning to pretreatment levels by day 30–40 (Fig. 1G). NKT (CD16+CD8+NKG2A+CD3+) cells were also depleted (data not shown). Altogether, these results show that DD administration to monkeys resulted in a significant but very transient (2 days) depletion of T effector cells following each intravenous infusion. At the same time, DD triggered a profound and sustained depletion of R-Tregs and NK cells and a short-term expansion of A-Tregs. Therefore, unlike initially anticipated, DD exerts multiple and variable effects on various peripheral blood leukocytes in primates.

In vitro effects of DD treatment on NK cells and Tregs

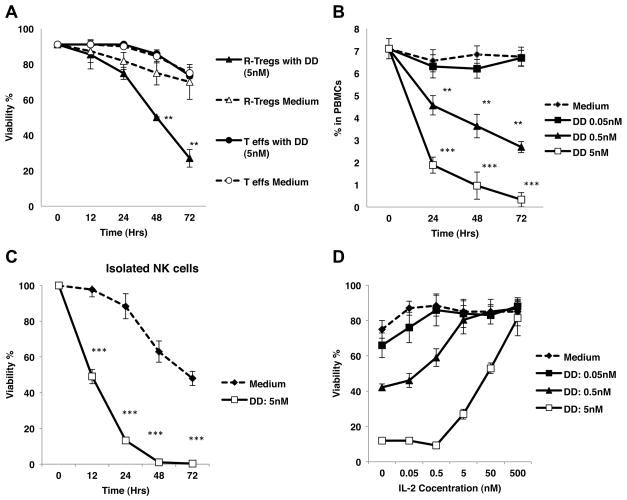

Next, we investigated the in vitro effects of DD on different monkey leukocyte subsets. A-Tregs (CD4+CD45RA−CD25++), R-Tregs (CD4+CD45RA+CD25++), and Teffs (CD4+CD45RA+CD25−) were sorted by FACS and cultured in the presence or absence of DD (5nM) for 72 hours. The frequencies of viable cells were determined via 7-AAD staining at different time points from 12 to 72 hours. As shown in Figure 2A, the percentages of viable Teffs remained constant throughout the entire period. We could not evaluate the in vitro effect of DD on the survival of A-Tregs because these cells die rapidly even in the absence of DD. In the absence of DD, the frequency of live R-Tregs remained constant for 72 hours, whereas DD treatment resulted in a 70% lethality among R-Tregs (Fig. 2A). In addition, exposure of R-Tregs to DD upregulated their expression of FoxP3 and CD95 for initial 12 hours, a result indicating that these cells had been activated (data not shown). Altogether, these results show that in vitro DD treatment did not affect the survival of Teffs while it activated all Tregs and caused the death of R-Tregs.

Figure 2. In vitro effects of DD treatment on NK cells and Tregs.

A: R-Tregs and Teffs were sorted by FACS and incubated with 5nM of DD for up to 72 hours. Whereas Teffs were resistant even after 72 hours exposure to DD, the viability of R-Tregs declined to 27% after 72 hours. (**P < 0.005 compared to medium alone). Cell death was measured by 7-AAD. B: Monkey PBMCs were incubated with various concentrations of DD, the percentage of NK cells among PBMCs decreased over time in a dose dependent manner. **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.001. C: NK cells were sorted by FACS and incubated with 5 nM DD for up to 72 hours. The viability of NK cells after exposure to DD significantly decreased when compared to medium alone. D: IL-2 competitively inhibited DD effects on NK cells in a dose-dependent fashion at 24 hours. Each experiment was performed at least three times using two different animals.

The percentages of live NK cells among PBMCs treated with DD (0.5–5 nM) decreased over time, in a dose dependent manner, while no effect was observed in controls incubated with medium alone (P< 0.001) (Fig. 2B). To determine whether DD directly affected NK cells, NK cells were sorted by FACS and incubated with 5 nM DD for up to 72 hours. NK cells viability significantly decreased as early as 12 hours after exposure to DD (Fig. 2C). Addition of IL-2 to the culture inhibited the effect of DD on NK cell death in a dose-dependent manner at 24 hours (Fig. 2D), thereby confirming that DD mediated its effect via IL-2R. A similar cytotoxic pattern was also observed in human NK cells (Data not shown).

These in vitro results recapitulate the effects observed following in vivo DD administration, including some but minimal depletion of Teffs, a rapid and massive cell death among NK cells and R-Tregs, and upregulation of the expression of various activation markers on Tregs. Finally, it is noteworthy that the rapid and spontaneous death of A-Tregs observed in vitro but not in vivo suggests that homeostatic survival of this Treg subset relies on some factors absent in our cell cultures.

Binding and internalization of DD by NK cells and Tregs

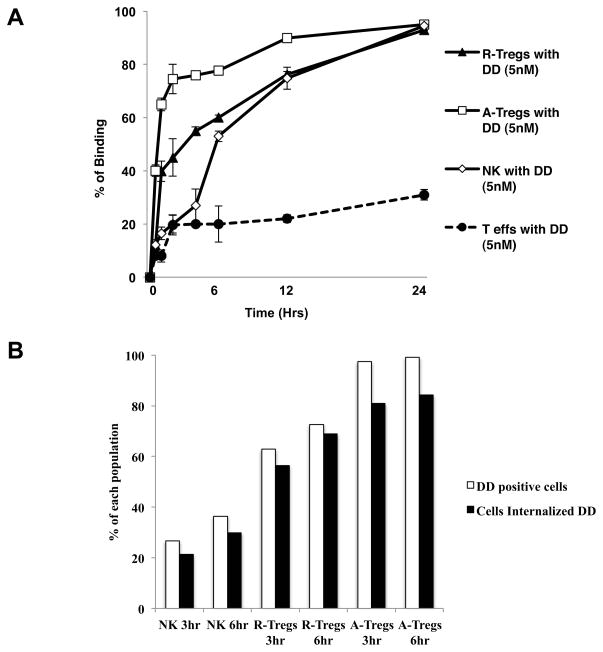

In another set of experiments, we studied whether the differential effects of DD on NK and Tregs is associated with differences in its binding and/or uptake by these cells. To address this question, NK cells, Teffs and each of the Treg subsets were isolated and incubated with DD (5 nM) labeled with the fluorescent dye, Alexa-647, for different periods of time ranging from 0 to 24 hours. The percentages of viable cells bound to DD were evaluated by FACS. As shown in Fig. 3A, 20% of Teffs and NK cells were bound to DD after 2 hours. In contrast, at 2 hours, 40% and 65% of R-Tregs and A-Tregs were labeled with DD, respectively. Subsequently, the number of Teffs bound to DD remained unchanged. While the numbers of NK cells and R-Tregs bound to DD increased over time and reached respectively 53% and 60% at 6 hours, 74.8% and 76.2% at 12 hours and was greater than 90% at 24 hours. Finally, the number of DD-labeled A-Tregs reached 90% at 12 hours and remained constant until the end of the assay. Likewise, the mean fluorescent intensity, representing the level of DD binding per individual cell, increased faster and was consistently higher in Tregs than NK cells. Representative histograms are shown in supplemental Fig. 2A and B. These results show that both Treg subsets bind DD in an accelerated fashion as compared to NK cells. Therefore, the higher cytotoxic effect of DD on NK cells as compared to Tregs cannot be attributed to increased binding to IL-2R by the NK cell population.

Figure 3. Binding and internalization of DD by NK cells and Tregs.

A: Isolated A-Tregs, R-Tregs and NK cells were incubated with Alexa-647 labeled DD and analyzed by FACS for DD binding. During the initial 6 hours, DD bound to both A-Tregs and R-Tregs faster than to NK cells. B: For quantification of internalization, 2 × 106 PBMCs were incubated with Alexa-647 labeled DD and analyzed after 3 or 6 hours. The white columns represent the percentages of the DD positive NK cells and R-Tregs/A-Tregs and the black columns represent the percentages of the cells with internalized toxin.

Next we compared NK cells and Tregs for their ability to internalize DD. Monkey PBMCs (2 × 106) were cultured with 5 nM of DD for 3 or 6 hours. The presence of intracellular Alexa-647-labeled DD in Tregs and NK cells was determined by imaging with a ImageStreamX® Imaging Flow Cytometer using a quantitative morphology based feature (Representative figures are shown in Supplemental Fig. 3A-C). The percentages of R-Tregs/A-Tregs bound to DD were 62.9%/97.4% at 3 hours and 72.5%/99.1% at 6 hours. Among these cells, DD-internalized R-Tregs/A-Tregs accounted for 89%/83% and 94%/85% of the cells at 3 hours and 6 hours respectively (Fig. 3B). On the other hand, the proportions of NK cells having taken up DD were 33.4% at 3 hours and 36.4% at 6 hours (Fig. 3B). Among these, 80% and 76% cells displayed intracellular DD at 3 and 6 hours, respectively. Therefore, while NK cells were more susceptible than Tregs to DD-mediated cytotoxicity, they exhibited a lower ability to bind and internalize DD.

Influence of IL-15 on DD-mediated depletion of NK cells and Tregs

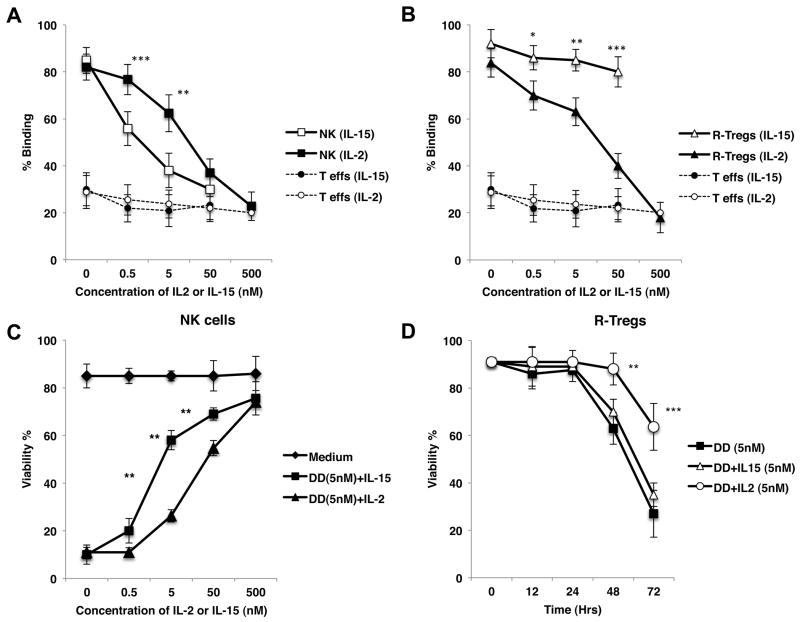

IL-15 is essential to the differentiation and homeostasis of NK cells and has been used to expand NK cells and enhance their functions (22–24). At the same time, IL-15 is known to compete with IL-2 through IL-2/15R β chain, since IL-15R shares β and γ subunits with IL-2R. Alternatively, IL-15 does not bind to IL-2Rα (25–27). Based upon these considerations, we hypothesized that IL-15 could competitively suppress the lethal effect of DD on NK cells but not on Tregs. First, we compared the ability of IL-15 to compete with DD for binding to NK cells and Tregs. Purified NK cells or R-Tregs were cultured with Alexa647-labeled DD for 24 hours in the presence of either IL-2 or IL-15. As expected, DD binding to both NK cells and Tregs was inhibited in the presence of its “natural competitor”, IL-2. Alternatively, IL-15 efficiently blocked the binding of DD to NK cells but not Tregs (Fig. 4A,B). It is noteworthy that IL-15 was more efficient in blocking DD binding than IL-2 itself, a result suggesting that IL-15 displays a higher affinity for IL-2Rβ-γ heterodimer than its natural ligand, IL-2. These results prompted us to investigate whether IL-15 could differentially alter the cytotoxic effects of DD on NK cells and Tregs. Purified monkey NK cells or Tregs were exposed to DD for 24 hours in the presence of either IL-15 or IL-2. As shown in Figs. 4C, and 4D, IL-15 effectively prevented DD-mediated NK cell death in a dose-dependent fashion. In fact, IL-15 inhibited DD-induced lethality more efficiently than IL-2 itself (** P<0.005) (Fig. 4C). In striking contrast, IL-15 had no effect on DD-mediated death of Tregs (Fig. 4D). Finally, we evaluated whether IL-15 could selectively block DD-mediated killing of NK cells but not Tregs in a mixed cell population. PBMCs (2 × 105 cells) were cultured with labeled DD for 24 hours in the presence of different doses of IL-15 or IL-2 cytokines. NK cells, R-Tregs and A-Tregs were evaluated for their viability and binding to DD. Similar to that observed with isolated cell subsets, IL-15 bound preferentially to NK cells and averted their death while it had no effects on Tregs (Supplemental Fig. 4A–D).

Figure 4. Influence of IL-15 on DD-mediated depletion of NK cells and Tregs.

A and B: Isolated monkey NK cells and R-Tregs were exposed to 5nM DD labeled with Alexa-647 in the presence of various concentrations of either IL-15 or IL-2. IL-15 was more effective than IL-2 in preventing DD from binding to NK (A), while IL-2 more efficiently blocked binding of DD to R-Tregs (B). As a comparison, the bindings of DD to Teffs in both conditions are also shown. These analyses were performed at 24 hours. C: IL-15 was more effective than IL-2 in preventing isolated NK cell death induced by DD at 24 hours. Prevention of cell death occurred in a dose-dependent fashion. D: Whereas addition of 5nM IL-2 prevented the cell death of purified R-Tregs exposed to DD, 5nM IL-15 did not prevent cell death of R-Tregs. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.001. Each experiment was performed at least three times using two different animals.

IL-15 prevents in vivo DD-mediated depletion of NK cells but not of Tregs

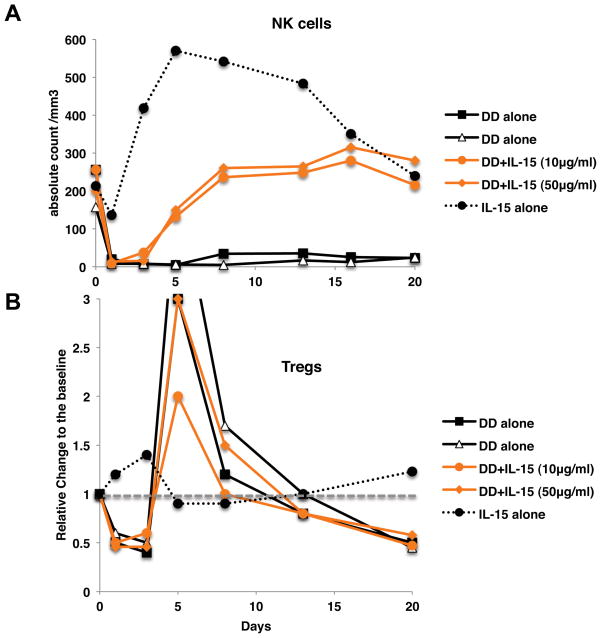

To investigate the in vivo effects of IL-15, two monkeys were injected intravenously with DD (8 μg/Kg) along with IL-15 (10 or 50 μg/Kg). Two control animals were treated with IL-15 alone. As previously reported, IL-15 induced a massive leukocyte extravasation resulting in peripheral blood lymphopenia during the first few days post-injection (28). Remarkably, IL-15 treatment resulted in a rapid and complete recovery of NK cells after DD treatment (Fig. 5A). In contrast, IL-15 didn’t affect in vivo depletion of Tregs induced by DD (Fig. 5B). These observations suggest that IL-15 might be a useful therapeutic agent to protect selectively NK cells from elimination in subjects being treated with DD.

Figure 5. IL-15 prevents DD-mediated in vivo depletion of NK cells but not of Tregs.

8 μg/kg of DD was co-administered with IL-15 of 10 μg/kg or 50 μg/kg on day 0. Two animals were treated by 10 μg/kg of IL-15 alone. A: Rapid and complete recovery of NK cells was observed by co-administration of IL-15, B: In contrast to NK cells, no effects on Tregs were observed by adding IL-15.

Discussion

Individual IL-2R subunits are expressed on various lymphoid cell populations while co-expression of CD25 (IL-2Rα), CD122 (IL-2Rβ) and CD132 (IL-2Rγ) subunits that form the high affinity IL-2R, is essentially confined to CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs and a few activated “conventional” T effector cells. Based upon this principle, the IL-2/DT fusion protein was expected to preferentially bind to and delete Tregs while sparing other leukocytes. Actually, our study shows that DD has multiple and distinctive effects on various leukocyte subsets in monkeys. This study confirms that DD treatment does mediate a partial (50–60%) and prolonged depletion of primate Tregs in vivo. However, our observations also show that this phenomenon is rather more complex than initially anticipated in that: 1) DD elicited an early expansion of Tregs displaying an activated phenotype (A-Tregs) and, 2) DD-mediated Treg depletion is restricted to resting Tregs (R-Tregs). The observation that many DD-exposed Tregs initially become activated before dying after 12–36 hours is reminiscent of another study in which T cells cultured with IL-2-DT first displayed elevated levels of cytoplasmic mRNA coding for IL-2R, c-myc and γIFN followed by a reduction of these mRNA levels by 20 hours (29). Following activation/expansion, it is likely that these A-Tregs ultimately succumb due to the effects of the diphteria toxin or via apoptosis caused by absence of continuous exposure to exogenous IL-2 (30). Conversely, while our in vitro assays clearly show that some R-Tregs are killed via DD exposure, R-Treg reduction due to conversion to A-Tregs cannot be ruled out in this study.

In addition to its effects on Tregs, DD treatment triggered some, although partial and short-lasting, depletion of effector T lymphocytes. Most importantly, exposure of monkey PBMCs both in vitro and in vivo caused a profound and durable elimination of NK cells. The phenotypic definition of macaque NK cells has been established (20, 31, 32) and we defined cynomolgus monkey NK cells as CD16+CD8+NKG2A+CD3- in this study. Although a recent study identified the presence of minor CD8α-NK cell subpopulation among CD8-CD16+CD3-CD20-CD14-cells in rhesus monkeys (33), they are presumed to comprise only <5–10% of total NK cells. Since CD16+CD3-CD20-CD14-CD8-population also contains substantial number of myeloid dendritic cells, we did not include CD8-NK cells in our analyses. Nevertheless, this observation might seem surprising since only 10% of NK cells express the IL-2Rα subunit while the vast majority of these cells display IL-2Rβ-γ heterodimers (34). However, it is noteworthy that previous studies by Re et al. have shown that cells expressing the intermediate affinity IL-2Rβ-γ could bind DD quite efficiently (18). Despite this, no NK cell depletion was observed in studies using the IL-2 diphtheria toxin of previous generation, DAB486-IL-2, at doses ranging from 1–10nM (35). Subsequent reengineering of this agent has led to the development of DAB389-IL-2 (DD), which has a higher Ka (association constant) and longer half-life than the original compound (36) and has been currently used clinically. Nevertheless, to our knowledge, no effect of DD on human or non-human primate NK cells has been reported so far (3, 4, 9). Our study shows unambiguously that DD delivered at doses ranging from 0.5 nM to 5 nM eliminates completely and durably NK cells in monkeys, an observation which has important implications for the design of anti-tumor therapies using this and future IL-2R-based immunotoxins. It remains unclear why DD treatment results in a complete depletion of NK cells while a significant number of Tregs are apparently not eliminated. Our results have shown that this phenomenon is not the result of differences in DD binding or internalization among these cell subsets. Therefore, it is likely that DD mediates different intracellular signals to NK and Treg cells or that these two cell types display different sensitivity toward diphtheria toxin. Additionally, the rapid homeostatic expansion of Tregs known to occur after leukopenia may account for the recovery of some Tregs. It is also conceivable that DD may convert Tregs to other subpopulations that are more resistant to cytotoxic effects of DD. Further studies are required to test these hypotheses.

Of potential importance to future DD clinical trials, we observed that IL-15 bound preferentially to IL-2R on NK cells and protected them from elimination by DD while it did not impact the depletion of Tregs in monkeys. This protective effect by IL-15 is presumably the result of competition between DD and IL-15. However, it is also possible that activation of NK cells via IL-15 confers additional resistance against DD. IL-15 cytokine is actually essential to the regulation of NK cell homeostasis and differentiation. Likewise, Administration of IL-15 or IL-15/IL-15Rα complexes has been shown to augment immunity against tumors and virus by potentiating NK and CD8+ T cell responses in mice (37–42). Similar expansion/activation of NK cells has also been reported in non-human primates treated with IL-15 with limited effects on CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs (28, 43, 44). Together with our results, this shows that in vivo IL-15 administration activates selectively NK cells through their IL-2R without affecting Tregs.

In summary, our study shows that while DD administration depletes a significant proportion of Tregs, it rapidly and durably eliminates all NK cells in non-human primates. Such depletion of potentially tumoricidal NK cells may explain why DD treatment has been only modestly successful in cancer patients. To address this problem, protocols might be designed to eliminate Tregs while sparing NK cells. Our study shows that this can be achieved in monkeys via co-administration of IL-15 with DD, which maintained Treg depletion while it spared and presumably potentiated NK cells. This suggests that IL-15 co-administration could be considered in future clinical treatments designed to enhance immunity against cancer and microbes by depleting Tregs in patients using IL-2R-based strategies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Amnis (Seattle, WA) for their assistance regarding DD internalization experiments.

Source of Support

This work was supported by grants from the NIAID U19 AI066705 grants, NIH 19 DK080652 and HL018446 and NIH U191066705 and PO1HL18646 and U01AI094374.

Abbreviations

- DD

Denileukin Diftitox

- Tregs

Regulatory T cells

- A-Tregs

activated Tregs

- R-Tregs

resting Tregs

- Teffs

effector T cells

References

- 1.Morse MA, Hobeika AC, Osada T, Serra D, Niedzwiecki D, Lyerly HK, Clay TM. Depletion of human regulatory T cells specifically enhances antigen-specific immune responses to cancer vaccines. Blood. 2008;112:610–618. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-135319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Litzinger MT, Fernando R, Curiel TJ, Grosenbach DW, Schlom J, Palena C. IL-2 immunotoxin denileukin diftitox reduces regulatory T cells and enhances vaccine-mediated T-cell immunity. Blood. 2007;110:3192–3201. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-094615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dannull J, Nair S, Su Z, Boczkowski D, DeBeck C, Yang B, Gilboa E, Vieweg J. Enhancing the immunostimulatory function of dendritic cells by transfection with mRNA encoding OX40 ligand. Blood. 2005;105:3206–3213. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahnke K, Schonfeld K, Fondel S, Ring S, Karakhanova S, Wiedemeyer K, Bedke T, Johnson TS, Storn V, Schallenberg S, Enk AH. Depletion of CD4+CD25+ human regulatory T cells in vivo: kinetics of Treg depletion and alterations in immune functions in vivo and in vitro. International journal of cancer. 2007;120:2723–2733. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salagianni M, Lekka E, Moustaki A, Iliopoulou EG, Baxevanis CN, Papamichail M, Perez SA. NK cell adoptive transfer combined with ontak-mediated regulatory T cell elimination induces effective adaptive antitumor immune responses. Journal of immunology. 2011;186:3327–3335. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dannull J, Su Z, Rizzieri D, Yang BK, Coleman D, Yancey D, Zhang A, Dahm P, Chao N, Gilboa E, Vieweg J. Enhancement of vaccine-mediated antitumor immunity in cancer patients after depletion of regulatory T cells. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2005;115:3623–3633. doi: 10.1172/JCI25947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rasku MA, Clem AL, Telang S, Taft B, Gettings K, Gragg H, Cramer D, Lear SC, McMasters KM, Miller DM, Chesney J. Transient T cell depletion causes regression of melanoma metastases. Journal of translational medicine. 2008;6:12. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-6-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foss F. Clinical experience with denileukin diftitox (ONTAK) Seminars in oncology. 2006;33:S11–16. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2005.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerena-Lewis M, Crawford J, Bonomi P, Maddox AM, Hainsworth J, McCune DE, Shukla R, Zeigler H, Hurtubise P, Chowdhury TR, Fletcher B, Dyehouse K, Ghalie R, Jazieh AR. A Phase II trial of Denileukin Diftitox in patients with previously treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer. American journal of clinical oncology. 2009;32:269–273. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318187dd40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrara JL. Novel strategies for the treatment and diagnosis of graft-versus-host- disease. Best practice & research. 2007;20:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Talpur R, Apisarnthanarax N, Ward S, Duvic M. Treatment of refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma with denileukin diftitox (ONTAK) Leukemia & lymphoma. 2002;43:121–126. doi: 10.1080/10428190210183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dang NH, Fayad L, McLaughlin P, Romaguara JE, Hagemeister F, Goy A, Neelapu S, Samaniego F, Walker PL, Wang M, Rodriguez MA, Tong AT, Pro B. Phase II trial of the combination of denileukin diftitox and rituximab for relapsed/refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. British journal of haematology. 2007;138:502–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dang NH, Hagemeister FB, Pro B, McLaughlin P, Romaguera JE, Jones D, Samuels B, Samaniego F, Younes A, Wang M, Goy A, Rodriguez MA, Walker PL, Arredondo Y, Tong AT, Fayad L. Phase II study of denileukin diftitox for relapsed/refractory B-Cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4095–4102. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Attia P, Maker AV, Haworth LR, Rogers-Freezer L, Rosenberg SA. Inability of a fusion protein of IL-2 and diphtheria toxin (Denileukin Diftitox, DAB389IL-2, ONTAK) to eliminate regulatory T lymphocytes in patients with melanoma. J Immunother. 2005;28:582–592. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000175468.19742.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnett B, Kryczek I, Cheng P, Zou W, Curiel TJ. Regulatory T cells in ovarian cancer: biology and therapeutic potential. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2005;54:369–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2005.00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knutson KL, Dang Y, Lu H, Lukas J, Almand B, Gad E, Azeke E, Disis ML. IL-2 immunotoxin therapy modulates tumor-associated regulatory T cells and leads to lasting immune-mediated rejection of breast cancers in neu-transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2006;177:84–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiyokawa T, Williams DP, Snider CE, Strom TB, Murphy JR. Protein engineering of diphtheria-toxin-related interleukin-2 fusion toxins to increase cytotoxic potency for high-affinity IL-2-receptor-bearing target cells. Protein engineering. 1991;4:463–468. doi: 10.1093/protein/4.4.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Re GG, Waters C, Poisson L, Willingham MC, Sugamura K, Frankel AE. Interleukin 2 (IL-2) receptor expression and sensitivity to diphteria fusion toxin DAB389IL-2 in cultured hematopoietic cells. Cancer research. 1996;56:2590–2595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foss FM. Interleukin-2 fusion toxin: targeted therapy for cutaneous T cell lymphoma. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2001;941:166–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mavilio D, Benjamin J, Kim D, Lombardo G, Daucher M, Kinter A, Nies-Kraske E, Marcenaro E, Moretta A, Fauci AS. Identification of NKG2A and NKp80 as specific natural killer cell markers in rhesus and pigtailed monkeys. Blood. 2005;106:1718–1725. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyara M, Yoshioka Y, Kitoh A, Shima T, Wing K, Niwa A, Parizot C, Taflin C, Heike T, Valeyre D, Mathian A, Nakahata T, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M, Amoura Z, Gorochov G, Sakaguchi S. Functional delineation and differentiation dynamics of human CD4+ T cells expressing the FoxP3 transcription factor. Immunity. 2009;30:899–911. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meazza R, Azzarone B, Orengo AM, Ferrini S. Role of common-gamma chain cytokines in NK cell development and function: perspectives for immunotherapy. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:861920. doi: 10.1155/2011/861920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moustaki A, Argyropoulos KV, Baxevanis CN, Papamichail M, Perez SA. Effect of the simultaneous administration of glucocorticoids and IL-15 on human NK cell phenotype, proliferation and function. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1067-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jakobisiak M, Golab J, Lasek W. Interleukin 15 as a promising candidate for tumor immunotherapy. Cytokine & growth factor reviews. 2011;22:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giri JG, Kumaki S, Ahdieh M, Friend DJ, Loomis A, Shanebeck K, DuBose R, Cosman D, Park LS, Anderson DM. Identification and cloning of a novel IL-15 binding protein that is structurally related to the alpha chain of the IL-2 receptor. The EMBO journal. 1995;14:3654–3663. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giri JG, Anderson DM, Kumaki S, Park LS, Grabstein KH, Cosman D. IL-15, a novel T cell growth factor that shares activities and receptor components with IL-2. Journal of leukocyte biology. 1995;57:763–766. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.5.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giri JG, Ahdieh M, Eisenman J, Shanebeck K, Grabstein K, Kumaki S, Namen A, Park LS, Cosman D, Anderson D. Utilization of the beta and gamma chains of the IL-2 receptor by the novel cytokine IL-15. The EMBO journal. 1994;13:2822–2830. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06576.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lugli E, Goldman CK, Perera LP, Smedley J, Pung R, Yovandich JL, Creekmore SP, Waldmann TA, Roederer M. Transient and persistent effects of IL-15 on lymphocyte homeostasis in nonhuman primates. Blood. 2010;116:3238–3248. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-275438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walz G, Zanker B, Brand K, Waters C, Genbauffe F, Zeldis JB, Murphy JR, Strom TB. Sequential effects of interleukin 2-diphtheria toxin fusion protein on T-cell activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1989;86:9485–9488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zorn E, Nelson EA, Mohseni M, Porcheray F, Kim H, Litsa D, Bellucci R, Raderschall E, Canning C, Soiffer RJ, Frank DA, Ritz J. IL-2 regulates FOXP3 expression in human CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells through a STAT-dependent mechanism and induces the expansion of these cells in vivo. Blood. 2006;108:1571–1579. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-004747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shields LE, Sieverkropp AJ, Potter J, Andrews RG. Phenotypic and cytolytic activity of Macaca nemestrina natural killer cells isolated from blood and expanded in vitro. Am J Primatol. 2006;68:753–764. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Webster RL, Johnson RP. Delineation of multiple subpopulations of natural killer cells in rhesus macaques. Immunology. 2005;115:206–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02147.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vargas-Inchaustegui DA, Demberg T, Robert-Guroff M. A CD8alpha(−) subpopulation of macaque circulatory natural killer cells can mediate both antibody-dependent and antibody-independent cytotoxic activities. Immunology. 2011;134:326–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malek TR. The biology of interleukin-2. Annual review of immunology. 2008;26:453–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waters CA, Schimke PA, Snider CE, Itoh K, Smith KA, Nichols JC, Strom TB, Murphy JR. Interleukin 2 receptor-targeted cytotoxicity. Receptor binding requirements for entry of a diphtheria toxin-related interleukin 2 fusion protein into cells. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:785–791. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Foss FM. DAB(389)IL-2 (denileukin diftitox, ONTAK): a new fusion protein technology. Clinical lymphoma. 2000;1(Suppl 1):S27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Epardaud M, Elpek KG, Rubinstein MP, Yonekura AR, Bellemare-Pelletier A, Bronson R, Hamerman JA, Goldrath AW, Turley SJ. Interleukin-15/interleukin-15R alpha complexes promote destruction of established tumors by reviving tumor-resident CD8+ T cells. Cancer research. 2008;68:2972–2983. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsunobuchi H, Nishimura H, Goshima F, Daikoku T, Suzuki H, Nakashima I, Nishiyama Y, Yoshikai Y. A protective role of interleukin-15 in a mouse model for systemic infection with herpes simplex virus. Virology. 2000;275:57–66. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chapoval AI, Fuller JA, Kremlev SG, Kamdar SJ, Evans R. Combination chemotherapy and IL-15 administration induce permanent tumor regression in a mouse lung tumor model: NK and T cell-mediated effects antagonized by B cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:6977–6984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stoklasek TA, Schluns KS, Lefrancois L. Combined IL-15/IL-15Ralpha immunotherapy maximizes IL-15 activity in vivo. J Immunol. 2006;177:6072–6080. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rubinstein MP, Kadima AN, Salem ML, Nguyen CL, Gillanders WE, Cole DJ. Systemic administration of IL-15 augments the antigen-specific primary CD8+ T cell response following vaccination with peptide-pulsed dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:4928–4935. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oh S, Perera LP, Burke DS, Waldmann TA, Berzofsky JA. IL-15/IL-15Ralpha-mediated avidity maturation of memory CD8+ T cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:15154–15159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406649101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berger C, Berger M, Hackman RC, Gough M, Elliott C, Jensen MC, Riddell SR. Safety and immunologic effects of IL-15 administration in nonhuman primates. Blood. 2009;114:2417–2426. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-189266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Waldmann TA, Lugli E, Roederer M, Perera LP, Smedley JV, Macallister RP, Goldman CK, Bryant BR, Decker JM, Fleisher TA, Lane HC, Sneller MC, Kurlander RJ, Kleiner DE, Pletcher JM, Figg WD, Yovandich JL, Creekmore SP. Safety (toxicity), pharmacokinetics, immunogenicity, and impact on elements of the normal immune system of recombinant human IL-15 in rhesus macaques. Blood. 2011;117:4787–4795. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-311456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.