Abstract

CD23+CD21highCD1dhigh B cells (Bin cells) accumulate in the LNs draining inflamed joints of the TNFα transgenic (TNFtg) mouse model of rheumatoid arthritis, and are primarily involved in the significant histological and functional LN alterations that accompany disease exacerbation in this strain. Here we investigate the origin and function of Bin cells. We show that adoptively transferred GFP+ sorted mature follicular B (FoB) cells home preferentially to inflamed LNs of TNFtg mice where they rapidly differentiate into Bin cells, with a close correlation with the endogenous Bin fraction. Bin cells are also induced in wild-type (WT) LNs after immunization with T-dependent antigens, and display a germinal center phenotype at higher rates compared to FoB cells. Furthermore, we show that Bin cells can capture and process antigen immune complexes in a CD21-dependent manner more efficiently than FoB cells, and express higher levels of MHCII and costimulatory antigens CD80 and CD86. We propose that Bin cells are a previously unrecognized inflammation-induced B cell population with increased antigen capture and activation potential, which may facilitate normal immune responses but may contribute to autoimmunity when chronic inflammation causes their accumulation and persistence in affected LNs.

Keywords: B-cells, Inflammation, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Lymph nodes, Immune complexes

Introduction

The involvement of B cells in the pathogenesis of several autoimmune disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus and autoimmune diabetes is well established (1–2); reviewed in (3). Although autoantibody production is still broadly considered to be primary effector mechanism of B cells in these diseases, recent research has highlighted other key B cell pathogenetic processes contributing to the establishment and maintenance of autoimmune states, including antigen presentation, T cell costimulation, and secretion of cytokines (4–8). Sifting through this multiplicity of potential effects by B cells to identify the key mechanisms in each specific condition is daunting, but essential for a full understanding of disease pathogenesis and the design of targeted therapies.

RA is one of the first autoimmune diseases in which B cell involvement was postulated based on autoantibody production, only to later fall in disfavor because of a lack of direct correlation between autoantibodies and pathogenesis (9–11). However, the recent success of B cell depletion therapy in RA patients refractory to other therapies has rekindled interest in the role of B cells in this disease (12–14). The observation that clinical improvement in patients does not always correspond with the reduction in serum autoantibody levels has focused the attention on the possibility of antibody-independent pathogenic function(s) for B cells in RA (15–16).

The process of inflammation is intrinsically tied to autoimmune manifestations through recruitment and differentiation of effector cells, mediation of tissue necrosis and destruction by cytolytic and proteolytic enzymes, induction of tissue swelling and pain (17–19). More interestingly from an immunological perspective, inflammation has also been linked to the onset of autoimmunity by causing alterations in T cell (and possibly B cell) subset balance, affecting central and peripheral tolerance mechanisms, and directly inducing the differentiation of tertiary lymphoid structures at target organs, such as the pancreas β-islets or the rheumatoid synovium, via the process of lymphoid neogenesis (20–23). B cells can be active participants in inflammatory processes: in addition to causing autoantibody/immune complex deposition and autoantibody-mediated cell death, they can be primary effectors of lymphoid neogenesis (23–25), can capture and transport immune complexes (ICs) to facilitate responses within lymphoid organs (26), and secrete both pro-inflammatory and regulatory cytokines (27–30).

On the other side, B cells themselves can be profoundly affected by environmental changes during inflammation (31–32). In particular, inflammatory cytokines have been shown to induce significant, specific changes in B lymphopoiesis as well as peripheral differentiation, which in turn may affect the tolerance vs. autoimmunity balance. For instance, chronic inflammation can induce IL-2-mediated apoptosis in marginal zone B cells, altering antigen trafficking and immune complex clearance in the spleen, IFN-α has been shown to provide an initial trigger for the differentiation of pro-inflammatory B effector-1 cells, reduced production of bone marrow CXCL12 during inflammation results in mobilization of immature B cells to the spleen and B cell activating factor (BAFF) can directly alter peripheral tolerance checkpoints for autoreactive B cells in RA (33–36). These and other findings have led in recent years to the emergence of a new appreciation of the influence of the inflammatory microenvironment on B cell development, differentiation, mobilization and survival (37).

The human TNF-α transgenic (TNFtg) mouse strain Tg3647 carries a single human TNF transgene copy and develops a slowly progressing inflammatory joint disease very similar to RA (38–39). In this model, a chronic and progressive inflammatory-erosive joint disease generally starts with ankle swelling, and advances to the knee and forelimbs over time (38–39). By using non-invasive small animal imaging techniques, the progression of the disease from ankle to the knee and the onset of arthritic flare have been shown to be accompanied by significant changes in the size, fluid content and draining function of the adjoining LNs. Moreover, both disease and the associated LN changes are reversible upon anti-TNF treatment (40–41). With further histological and flow cytometric analysis, we demonstrated that B cells are involved in the observed structural alterations of the affected TNFtg popliteal and iliac LNs (PLNs and ILNs) from the earliest stages of disease (42–43). A unique B cell subset (B cells in inflamed nodes, or Bin cells) characterized by a CD23+ CD21high CD1dhigh surface phenotype was found to dramatically accumulate specifically in the LNs draining TNFtg inflamed joints, and to be primarily involved in the histological disruption of the affected LNs (42–43). We also showed that B cell depletion ameliorates disease in TNFtg mice, highlighting a previously unrecognized role of B cells in this model (42).

The Bin population phenotype does not correspond to any of the main mature B cell subsets in the mouse periphery, but shares similarities with some immature spleen subsets (44), as well as with B cells with regulatory functions (B-regs or B-10 cells) observed in several autoimmune models (45–48). The functional significance of high levels of CD21 (complement receptor 2, involved in immune complex capture, but also a receptor for CD23 and possibly other surface and secreted molecules) and/or of CD1d (involved in presentation of glycolipid antigens) (49) on these cell types is still unclear. However, it is known that engagement of CD21 on B cells can lower the threshold of B cell activation (50–52); reviewed in (53), and high expression of CD1d on a subset of B cells is linked to their regulatory function (47, 54).

Given the evidence linking Bin cells to the structural/functional alterations in TNFtg LNs, and to disease pathogenesis and progression in this model, it is important to identify their origin and functional characteristics. Here we describe the results of further experiments aimed at addressing these questions, which show that Bin cells can directly differentiate locally from mature conventional follicular B (FoB) cells within inflamed LNs, and that they display an enhanced ability to capture and process antigen via CD21 and to exhibit a germinal center phenotype during T cell–dependent immune responses. This suggests a new link between the inflammatory microenvironment and B cell function in peripheral lymphoid organs, with general relevance to immune responses in normal and autoimmune conditions.

Materials and Methods

Mice

All experimental procedures involving mice were performed under approval of the University of Rochester Committee on Animal Resources, and according to all applicable federal and state regulations. All the mice used in this study were in the C57BL/6 genetic background. The 3647 line of human TNF-α transgenic (TNFtg) mice (38) was originally obtained from Dr. George Kollias (Institute of Immunology, Alexander Fleming Biomedical Sciences Research Center, Vari, Greece) and maintained by breeding with WT C57BL/6 mice. For all the adoptive transfer and immunization experiments TNFtg mice and age-matched WT littermates were used. Transgenic mice with an enhanced GFP (EGFP) cDNA under the control of a chicken beta-actin promoter (55) were maintained by breeding to WT mice. CD45.1 congenic mice were obtained from Jackson laboratory and maintained by sibling inbreeding. OT-II mice (56) were used as source of OVA peptide-specific CD4+ T cells.

Flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions were prepared from lymphoid organs by mechanical disruption, and stained with a mixture of fluorochrome-conjugated anti-mouse monoclonal antibodies: B220 (RA3-6B2), IgM (11/41), CD80 (16-10A1), GL7 (GL7), PD-1 (J43), CD62L (MEL-14), CD44 (IM7), CD11b (M1/70), CD11c (N418), CD45.1 (A20), CD45.2 (104) from eBioscience, CD19 (6D5), CD21/35 (7E9), CD23 (B3B4), CD4 (GK1.5), CD86 (GL-1) from Biolegend and CD21/35 (7G6), CD1d (B3B4), I-A/I-E (M5/114.15.2), CD95 (JO2), CXCR5 (2G8) from BD Pharmingen, followed by PE-Texas Red streptavidin (Invitrogen) staining if biotin-conjugated antibody was included in the staining panel. All the samples were stained for dead cell exclusion using Live/Dead fixable violet dead cell stain kit (Invitrogen). Samples were run on a 12-color LSRII cytometer (Becton Dickinson Pharmingen) and analyzed by FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR). Bin cells were defined as CD19+ or B220+, CD23+CD21high and confirmed to be CD1dhigh on separate gating. Gates for these markers were defined for every experiment based on their distribution on parallel samples of spleen B cell subsets (CD23+ CD21low FoB vs CD23lowCD21highCD1dhigh marginal zone B cells).

Adoptive transfer experiments

Single cell suspensions were generated from WT EGFP-transgenic mouse spleens, and after hypotonic red blood cell lysis, cells were stained with anti-B220, anti-CD23 and anti-CD21/35. GFP+ FoB cells (CD23+CD21low) were sorted using a Becton Dickinson FACSAria cell sorter. 9–12 × 106 GFP+ FoB cells were transferred into 4–6 month-old WT or TNFtg male recipients via tail vain injection. 20 or 72 h after transfer, single cell suspensions of peripheral lymphoid organs were stained for flow cytometry analysis.

In vivo proliferation analysis

CD19+ cells were purified from spleen of CD45.1+ mice by positive selection by MACS (Milteny Biotec). The purified B cells were labeled with 1.25μM CFSE (Cell Trace CFSE, Molecular Probes). 18–20×106 CFSE-loaded CD45.1+ CD19+B cells were transferred by tail vein injection into CD45.2WT or TNFtg recipients. 72 h later, the cells from lymphoid tissues were harvested and live cells were analyzed for expression of CD19 and CD45.1 and the proliferation of CD19+CD45.1+ B cells was measured based on CFSE dilution. CFSE-loaded cells were tested for proliferation in parallel by in vitro stimulation with 20μg/ml LPS in complete RPMI medium, 10% fetal bovine serum.

Immunizations

WT and TNFtg mice (3–4 mo of age) were immunized in one footpad with 25μg of chicken OVA (Sigma Aldrich) in CFA (Sigma Aldrich), 20μl final volume. 50μl of a 50:50 (vol/vol) solution of 0.5mg/ml FITC in acetone/dibutylphthalate (25μg FITC total) was applied by painting to the immunized footpad skin at d 13 after immunization. On d 14 the animals were sacrificed, PLN cells were harvested and stained for analysis by flow ctyometry.

For detection of antigen capture by B cells (15h immunization experiments), FITC-OVA conjugate (Molecular Probes) was mixed in CFA and 20μl of emulsion containing 50μg of antigen conjugate was injected into one footpad of each animal, the draining LN cells were harvested 15h later and stained for flow cytometry analysis.

For detection of antigen processing by B cells, DQ-OVA (Molecular Probes) was mixed with CFA and 20μl of emulsion containing 50μg of OVA was injected into one footpad of each animal. 20h after immunization draining LN cells were harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry. Cells harboring processed DQ-OVA (Ex/Em: 505/515nm) were detected by fluorescence in the FITC channel. In all experiments, PLNs from the contralateral unimmunized leg were used as paired controls.

Hyper-immune serum preparation

Hyper-immune serum against OVA was prepared by immunizing C57Bl/6 mice with 50μg of OVA three times at 2-week intervals (57). Alum (Imject Alum, Pierce) was used as adjuvant in primary i.p. immunization and IFA (Sigma Aldrich) was used for secondary and tertiary subcutaneous immunization. Ten d after the last immunization, sera were collected, pooled and used for preparation of ICs.

In vitro immune complex preparation and cell loading

Insoluble ICs were prepared in U bottom 96-well plate by incubation of FITC-OVA with the pooled hyperimmune serum at 37°C for 2h (57), followed by two washes in RPMI medium (Invitrogen) and centrifugation at 1000g, 4°C for 10min, to eliminate unbound materials. Inactivation of serum complement in control experiments was carried out by incubation at 56°C for 1h prior to use in IC preparation. Total PLN cells were harvested from TNFtg mice and left untreated or pre-treated with 10μg/ml of CD21-blocking antibody (anti-CD21/35, Clone 7G6, BD Pharmingen)(50) or isotype control (Clone A95-1, BD Pharmingen) for 1h. 0.5×106 cells were added to the generated ICs in 96 well plates and incubated for 30 min, extensively washed and stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies to B220, CD3, CD23 and CD21/35 (Clone 7E9, not competing with the 7G6 clone epitope) for flow cytometry analysis.

Adjuvant-mediated Bin induction

A 50:50 (vol/vol) of Alum, IFA in PBS or 10μg of CPG (ODN 2006: 5-TCG TCG TTT TGT CGT TTT GTC GTT –3) in PBS were prepared and 20–25μl volume of each preparation was used for foot-pad injection. The same volume of PBS was injected into contralateral footpads as control. On day 10 after injection, PLN cells were harvested for flow cytometry analysis.

ELISA

Immulon 1B 96-well plates (Thermo Labsystems) were coated with 5μg/ml OVA and blocked with 3% BSA. Serum samples were diluted in 0.1% BSA and transferred to the plate in duplicates. Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Southern Biotech) and Sigma 104 phosphatase substrate (Sigma) were used to detect anti-OVA IgG. IFN-γ in B: T co- culture supernatants, was measured using AN-18 mouse IFN-γ ELISA kit (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Th1 polarization

Total lymph node cells were harvested from OT-II mice and cultured with 1μg/ml OVA323-339 peptide (InvivoGen) and 0.1ng/ml IL-12p70)(PEPROTECH) to activate and polarize naïve CD4 T cell toward Th1. Cells were checked daily to prevent over growth. IL-7 (1ng/ml) (PEPROTECH) was added to the culture from day 4 to day 7 and resting cells on day 14 were used for co-culture experiments.

B: T Co-culture assay

Sorted FoB (CD23+CD1dlo) or Bin cells (CD23+CD1dhi)were co-cultured with resting Th1 polarized OT-II T cells (1:10) in 50μl/well in triplicates with or without 5 μg/ml OVA323-339. After 36 h, the culture supernatants were harvested and IFN-γ secretion was measured by ELISA.

Statistical analysis

Linear regression using Pearson’s coefficient was used to analyze the correlation between exogenous Bin (GFP+) and endogenous Bin cells in adoptive transfer experiments. Non-parametric two-tailed Mann-Whitney test for unpaired comparisons and two-tailed Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test for paired variable groups were used. ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-test was used for multiple group comparisons. Graphs were generated with Graph Pad Prism 5 or Microsoft Excel.

Results

B cells are preferentially recruited to TNFtg inflamed LNs and quantitatively acquire a Bin phenotype

Accumulation of Bin cells in large numbers in inflamed LNs of TNFtg mice could be due to the migration of a specific B cell subset/lineage, or their in situ differentiation from precursor cells of a different phenotype, including conventional CD23+CD21low FoB cells, or transitional/marginal zone precursor cells with a CD23+CD21high phenotype. To test the hypothesis that Bin cells may differentiate from conventional FoB cells, GFP+ CD23+ CD21low B cells were sorted by FACS from the spleen of non-TNFtg GFP-transgenic mice (supplementary Fig. S1A) and adoptively transferred into WT and TNFtg recipients. 72h later, single cell suspensions were generated from spleens, PLNs, MLNs, pooled ALN and BLNs of recipients, and the resident cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. A higher fraction of GFP+ B cells were consistently recovered from inflamed LNs (PLNs, ALNs+BLNs) compared to their WT counterparts and TNFtg non-inflamed sites (Fig1. A)

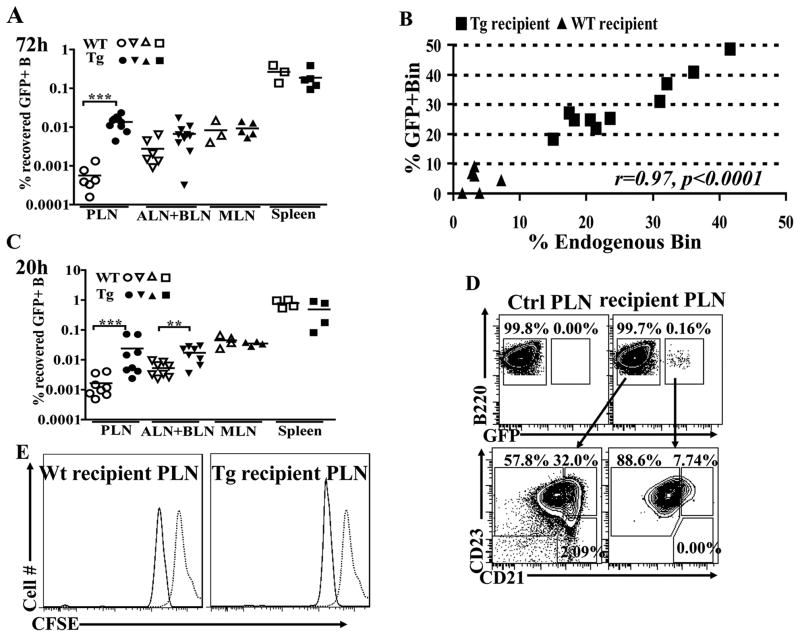

Figure 1. Homing and Bin differentiation of adoptively transferred FoB cells with no detectable proliferation.

A. The indicated peripheral lymphoid organs (PLNs, pooled ALNs+ BLNs, MLNs, and spleen) were harvested from WT (open symbols) and TNFtg (filled symbols) recipients 72h after adoptive transfer of sorted normal GFP+ FoB cells, and the fractions and numbers of total B cells were enumerated by flow cytometry. The percentage of total transferred GFP+ B cells recovered from the different lymphoid organs is shown. B. Quantitative correlation between the fraction of endogenous (GFP−) Bin and exogenous GFP+ Bin cells in PLNs of TNFtg (squares) or WT (triangles) hosts at 72 h after transfer. A very strong and significant correlation (Pearson’s correlation coefficient r=0.97, p<0.0001) is observed. C. Recovery percentages of total transferred GFP+ FoB cells after 20 h, analyzed as in panel A. A significantly higher fraction of transferred B cells are recovered from inflamed LNs (PLNs and, to a lesser extent, ALNs+BLNs) of TNFtg animals already at 20 h. D. Top: GFP+ transferred B cells (live/IgM+B220+gated) in one representative plot from a non-recipient (Ctrl PLN) and representative TNFtg recipient PLN after 20h transfer to show GFP gating strategy. Bottom: B cells in GFP− (left panel) and GFP+ (right panel) gates in the recipient TNFtg PLN shown above were analyzed for Bin and FoB cell distribution. Note the appearance of Bin-phenotype cells in the GFP+ subset as early as 20h. E. CFSE-labeled, CD45.1+CD19+ cells transferred to WT and TNFtg recipients (CD45.2+) and 72h later, proliferation was assessed based on CFSE dilution of live /CD45.1+ CD19+ gated cells in PLNs. Minor fluorescent loss in the overall population is observed in ex vivo samples, 72h after transfer (solid line), compared to the freshly stained cells at time 0 (dotted line), but no proliferation was detected. Panels A–C show combined results of 2 independent experiments for each time point. WT (n=3) and TNFtg (n=5) in A–B and WT and TNFtg (n=4) in C–E. Panel E, histogram representative of 2 independent experiments.**p<0.01, *** p<0.001, two-tailed Mann-Whitney test.

Analysis of the recovered GFP+ fractions in individual recipients showed that a significant fraction of transferred GFP+ cells in TNFtg PLNs had acquired a Bin phenotype. Strikingly, there was a highly significant correlation (r= 0.97, p<0.0001) between the fraction of GFP+ exogenous Bin cells and that of the host endogenous Bin cells in the same recipients’ PLNs (Fig. 1B). Although the fraction of GFP+ Bin varied by organ, a similar correlation with endogenous Bins was found in other inflamed LNs (ALNs+BLNs, r=0.9, p<0.01, Fig. S1B), and to a lesser extent in the spleen (r=0.8, p=0.02, Fig. S1C), while the correlation was near but did not reach the significance threshold for MLNs (r=0.7, p=0.06, Fig. S1D). Similar results were obtained after transfer of total CD19+ WT LN cells into TNFtg or WT recipients, regardless of the initial fraction of Bin-like cells (data not shown). Thus, Bin cells can differentiate locally from mature FoB cells within a pro-inflammatory LN microenvironment, rather than being a distinct subset migrating into inflamed nodes, and their phenotype induction is the result of local signals acting quantitatively on the B resident cells.

In addition to the differentiation of Bin cell, another notable change observed in TNFtg PLNs is the massive accumulation of B cell numbers as disease progresses (42). This could be due to local proliferation, preferential homing or retention of B cells in the affected nodes, or a combination thereof. As noticed above (Fig. 1A), a higher fraction of the transferred GFP+ B cells were recovered from inflamed LNs in TNFtg mice compared to other sites or to WT recipients at 72h after adoptive transfer. This paralleled the accumulation of endogenous B cells in inflamed LNs. As trafficking studies have shown that the average time of permanence of B cells within a LN is about 24 hours after entrance (58), a new set of adoptive transfer experiments were performed over a shorter time (20h) to distinguish between preferential migration/recruitment into the inflamed nodes and cell retention. In this shorter adoptive transfer period, only the first wave of immigrant B cells would be expected to be detectable in each examined LN. The results showed that a significantly higher number of transferred GFP+ FoB cell enter the TNFtg LNs compared to WT LNs already at 20h, suggesting that preferential homing is a primary mechanism for B cell accumulation in the inflamed nodes (Fig1. C), consistent with previous results on inflammation-mediated lymphocyte recruitment to LNs (59). Interestingly, a significant fraction of the transferred cells was shown to already display a Bin phenotype at this earlier time point after their entrance into the inflamed LNs (4.2 ±6.0% GFP+ Bin in WT vs. 8.3±1.8% GFP+Bin in Tg PLNs, p=0.02,) (Fig. 1D).

To rule out a contribution of proliferation in the local accumulation of B cells in the inflamed nodes of TNFtg mice, magnetically purified CD19+ splenic B cells from CD45.1+congenic WT mice were loaded with CFSE and transferred into either WT or TNFtg CD45.2+ recipients. 72h later, the CFSE dilution on transferred CD45.1+ B cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. No detectable proliferation of CD45.1+-gated B cells was found in either recipient strain (Fig. 1E)

Taken together, these findings indicate that TNFtg LNs draining arthritic joints are able to recruit higher numbers of recirculating B cells, and that the milieu in the node then quantitatively induces the immigrant B cells to acquire the Bin phenotype in the absence of proliferation. Thus, the massive accumulation of total B and Bin cells responsible for TNFtg structural and functional PLN alterations is a consequence of processes intrinsic to the inflamed nodes.

Bin cells and immune responses in TNFtg and WT LNs

Our previous findings have shown that TNFtg PLNs do not appear to be undergoing antigen-specific immune responses, and that Bin cells within the nodes do not show signs of activation or antigen-dependent clonal expansion (42). We wondered however whether Bin cells would be able to engage in normal immune responses when appropriately challenged, and whether the massive expansion of Bin cells in TNFtg LNs would affect the node’s ability to respond to immunization. To address these questions, TNFtg and WT mice were immunized in one footpad with OVA in CFA, and 2 weeks later the B and T cell subsets in immunized and non-immunized contralateral PLNs were analyzed by flow cytometry.

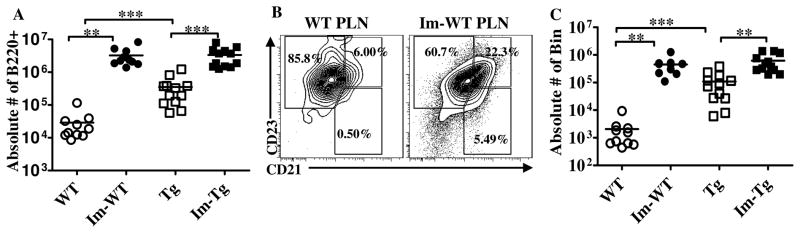

The absolute number of B cells in immunized PLNs of both TNFtg and WT mice increased significantly compared to their unimmunized counterparts (Fig. 2A), as did the relative percentage of B cells within the nodes (18.4±7.5% in unimmunized to 34.2±9% in immunized PLNs, p = 0.002 for WT and 37.1±6.5% to 44±11%, p= 0.0005 for TNFtg PLNs). Unexpectedly, the percentage of Bin in immunized WT PLNs also increased significantly (27±10% vs.7±4% in unimmunized contralateral PLNs, p=0.002,) (Fig. 2B), As a result, despite the dramatic differences in the baseline numbers of Bin cells, 2-week immunized PLNs from both TNFtg and WT harbored similar numbers of CD23+ CD21high CD1dhigh Bin cells (Fig. 2C). This previously unrecognized increase in Bin-like B cells in the immunized LNs of WT mice is consistent with the adoptive transfer findings above, which suggest that environmental cues in the nodes’ inflammatory milieu can induce the Bin phenotype in normal FoB cells. Similarly to adoptively transferred cells, induction of Bin cells after immunization occurs rapidly, with increased Bin cells detectable in immunized WT PLNs already 20h post immunization compared to unimmunized contralateral nodes (from 2.7± 0.9% to 4.2±1.4%, p= 0.03)

Figure 2. B cell numbers and subsets in WT and TNFtg PLNs 2 weeks after footpad immunization.

A. Absolute numbers of live B220+ B cells in immunized (filled symbols) and contralateral unimmunized (open symbols) PLNs of WT (circles) and TNFtg (squares) mice. Im-WT and Im-Tg: immunized PLNs, WT and Tg: unimmunized contralateral PLNs. Although larger numbers of B cells are present in the TNFtg LNs at baseline, after immunization the values in WT and TNFtg equalize. B. Representative flow cytometry plot comparing B cell subsets in unimmunized (left) and immunized (right) PLNs from a WT mouse. Note the increased percentage of Bin after immunization. C. Absolute numbers of CD23+ CD21high CD1dhigh Bin cells in immunized and unimmunized PLNs from WT and TNFtg mice. Combined results of 3 independent experiments, WT(n=10) TNFtg(n=12). **p<0.01, *** p<0.001, Mann-Whitney test for analysis between groups (WT vs. TNFtg), or two-tailed Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test for analysis within a group (WT or TNFtg).

To test whether inflammatory signals alone could induce Bin cell formation, WT mice were injected with either alum, CpG DNA or incomplete Freund’s adjuvant in one footpad and PBS in contralateral footpad. Ten days after injection, the PLNs draining the adjuvant-injected sites were compared to contralateral footpads. Increased frequency and absolute numbers of Bin phenotype cells were found in PLNs draining adjuvant-injected sites (Fig. S2A, B). Together with the finding of Bin cells in TNFtg LNs in the absence of significant B or T cell activation, these observations suggest that Bin cell induction is primarily dependent on inflammation, and not antigenic stimulation.

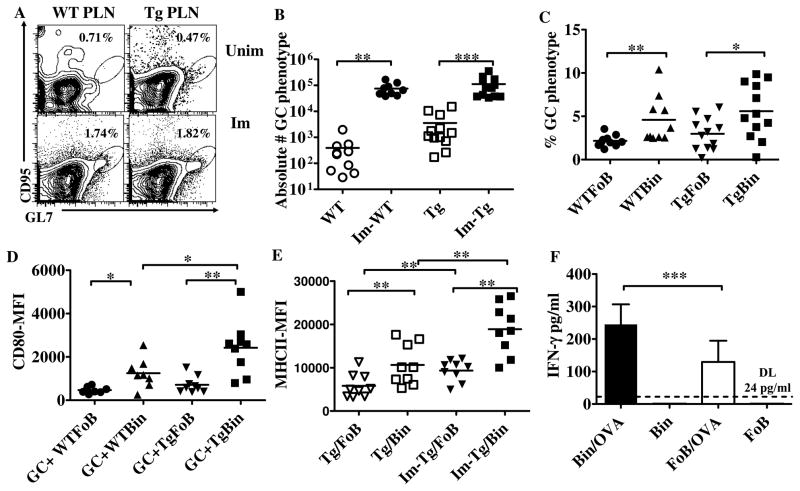

The numbers of germinal center (GC) B cells in 2-week immunized PLNs, based on co-expression of CD95 and the GC-specific marker GL7, was similar in TNFtg and WT mice (Fig. 3A,B). However, when B cells were gated based on their FoB and Bin phenotype and analyzed for GC marker expression, a higher fraction of Bin cells within both WT and TNFtg immunized LNs displayed the GC phenotype compared to the FoB cells in the same node (Fig. 3C). Thus, Bin cells not only can participate actively in T-dependent immune responses, but in fact may be more readily involved in the GC reaction. Analysis of surface markers on GC+ B cell subsets showed that Bin cells stain more intensely with an anti-CD80 antibody compared to their FoB counterparts (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, MHCII expression was higher on Bin cells than FoB cells in both unimmunized and immunized PLNs of TNFtg mice (Fig. 3E). To test whether Bin cells are intrinsically more capable of stimulating T cells, sorted Bin and FoB cells were co-cultured for 36 h with Th1-primed OT-II cells in the presence or absence of OVA peptide, and the supernatants were subjected to ELISA for IFN-γ. T cells stimulated by Bin cells in this manner secreted significantly higher levels of IFN-γ than those stimulated by FoB cells (Fig. 3F). In vivo evaluation of T cell subsets revealed similar percentages and absolute numbers of total CD4+ and follicular helper T cells (TFH), as well as of both CD62Lhigh CD44high central memory and CD62LlowCD44high effector/memory CD4+ T cells in immunized WT and TNFtg PLNs (data not shown). Finally, consistent with the comparable levels of activation observed in TNFtg and WT B cells, serum titers of anti-OVA IgG in WT and TNFtg mice, measured semi-quantitatively using a standard immunized reference serum, were also similar (arbitrary units, 1.8±0.5 in WT vs. 1.0±0.2 in TNFtg, p=0.11).

Figure 3. B cell activation in immunized WT and TNFtg PLNs.

A. Plots show gated live/B220+ B cells from representative unimmunized (top) and immunized PLNs (bottom) of WT (left) and TNFtg (right) mice, plotted for expression of GC markers (CD95, GL7). B. Absolute numbers of CD95+ GL7+ B cells in immunized and unimmunized PLNs of WT and TNFtg mice. Similar numbers are observed after immunization in WT and TNFtg mice. Combined results of 3 independent experiments are shown. C. B cells in immunized WT and TNFtg PLNs were gated for Bin and FoB phenotypes, and the percentage of cells of each subset that are CD95+ GL7+ is shown (combined data from 3 independent experiments). In both WT and TNFtg PLNs on average Bin cells are twice as likely to display a GC phenotype as FoB cells. D. Mean fluorescent intensity of CD80 on the surface of Bin and FoB cells with a GC phenotype in immunized PLNs. In both WT and TNFtg, GC Bin cells express higher levels of CD80 than GC FoBs. E. Mean fluorescent intensity of MHCII on the surface of Bin and FoB cells harvested from unimmunized and immunized PLNs in TNFtg mice. Bin cells express more MHCII on their surface than FoB cells both at baseline and after immunization. Combined results of 2 independent experiments, WT (n=10), TNFtg (n=12) in A–C, WT (n=8), TNFtg (n=9) in D and TNFtg (n=9) in E. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, *** p<0.001, two-tailed Mann-Whitney test for analysis between the groups (WT vs. TNFtg), two-tailed Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test for analysis within a group (WT or TNFtg).

Together, these data indicate that despite significant baseline difference in B cell subsets between WT and TNFtg PLNs, exposure to a foreign antigen elicits similar responses in the two strains, and that in fact the generation of Bin-phenotype cells is a physiological component of responses to inflammation in WT mice as well. Furthermore, the higher rate of acquisition of GC B cell markers and expression of antigen presentation and costimulatory molecules by Bin cells, reflected in their enhanced ability to activate T cells in vitro, strongly suggest that this inducible subset can become more readily involved in GC reactions and humoral immune responses.

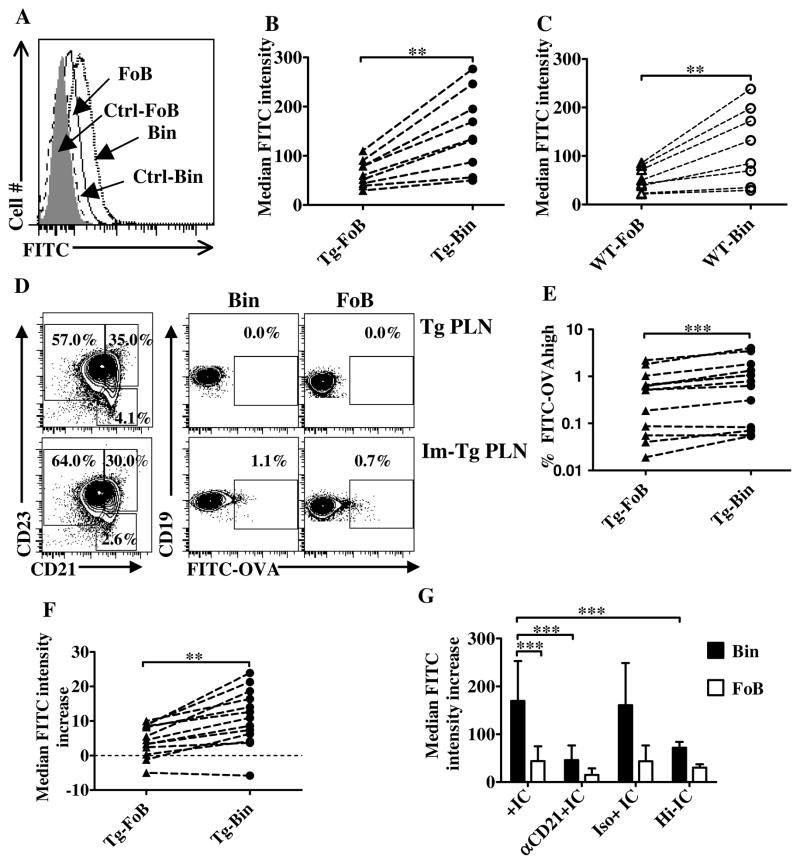

Bin cells capture antigen more efficiently than their FoB counterparts

CD21 binds to CD3d-coated ICs and its engagement has been shown to lower the threshold for B cell activation and enhance antigen presentation function (50, 60–61). Thus, we tested the hypothesis that Bin cells, may be capable of capturing non-cognate ICs, as well as of processing them for presentation. We first used the contact sensitizing agent FITC, which has been shown to concentrate to ICs and to be captured by B cells in draining LNs after skin painting of mice (62). FITC was applied on the immunized footpad of mice 13 d after OVA/CFA immunization, and one d later PLN cells were harvested and analyzed to measure FITC capture by B cell subsets, as detected by FITC median fluorescence intensity (md.f.i.) on Bin vs FoB cells. Median rather than mean fluorescence intensity is a better representation of the population in this case because it is less susceptible to the effects of rare large outlier values from the FITC-high population. Bin cells in immunized TNFtg PLNs showed significantly stronger FITC intensity on their surface (Fig. 4A), with average md.f.i. over 2-fold higher than FoB cells in the same PLN (149±80 on Bin vs. 65± 27 on FoB, p=0.004) (Fig. 4B). Similar results were observed for Bin cells in immunized WT PLNs (120±78 on Bin vs. 52±25 on FoB, p=0.008) (Fig. 4C). The population-wide shift to higher FITC staining by Bin cells indicates that these cells are more capable than FoB cells to capture non-cognate ICs.

Figure 4. Enhanced non-cognate immune complex capture by Bin cells.

A. Representative plot of FITC capture by B cell subsets one d after FITC application on 2-week immunized footpad. Histograms show FITC intensity on the surface of Bin (dotted line) and FoB (solid line) cells harvested from an immunized TNFtg PLN compared to the same subsets from an untreated PLN control (Ctrl), Ctrl-FoB (shaded) and Ctrl-Bin (dashed line). B, C. Pairwise comparison of median FITC fluorescence intensity on gated FoB and Bin cells in individual immunized TNFtg (B) and WT PLNs (C). Combined results of 2 independent experiments are shown. WT (n=8), TNFtg (n=9) in B–C. D. Representative plots of FITC-OVA capture by B cell subsets in a TNFtg PLN 20h after immunization. B cells (live/CD19+ gated) from both unimmunized (top) and immunized (bottom) PLNs were analyzed for FITC intensity on their surface. Left panels, Bin/FoB fractions and gating strategy. Bin (center panels) and FoBs (right panels) were plotted for FITC-OVA binding, and the gate for FITC-high cells is shown. E. Percentage of FITC-OVA-high bearing cells in immunized TNFtg PLNs. F. Increase in median intensity of FITC fluorescence (vs. unimmunized contralateral PLN cells) on the surface of FoB and Bin cells harvested from individual TNFtg PLNs 20h after immunization. Combined results of 3 independent experiments (n=13) in E–F. G. TNFtg PLN cells were left untreated or pre-treated with a CD21-blocking antibody or its isotype control, loaded or not loaded with in vitro-generated FITC-OVA ICs or Hi-IC for 30min, and analyzed by flow cytometry for B cell markers. The graph shows the median fluorescent intensity of FITC on FoBs (empty bars) or Bin (filled bars) subsets in the different conditions as indicated. Bin cells stain more brightly than FoBs with FITC-labeled ICs, and a major decrease in FITC intensity, down to or close to baseline, is observed following pre-treatment with a CD21-blocking antibody. Data show md.f.i numbers after background (unloaded cell self-fluorescence) subtraction from 8–12 replicate experiments. B,C,E,F: **p<0.01, *** p<0.001, two-tailed Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. G: ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-test.

To confirm these results in a more specific system, we repeated the experiments using FITC-conjugated OVA for footpad immunization in CFA, followed by harvesting PLN cells 15h after immunization, i.e. before any significant expansion of antigen-specific B cells. As depicted in Figure 4D–F, a higher percentage of Bin cells appear bright-positive for FITC compared to FoB cells in the majority of mice tested, with an average increase of 1.7 fold in FITC-high Bin cells percentage over FoB cells (Fig. 4D,E). In addition, the entire population of Bin cells showed a small but significant increase in FITC-OVA binding (Fig. 4F).

To test whether high expression of CD21 on Bin cells was directly responsible for their higher antigen capture potential, TNFtg PLN cells were pre-incubated with either a CD21-blocking antibody (50, 63) or its isotype control, or left untreated, and then incubated with in vitro-generated FITC-OVA ICs or heat-inactivated IC (Hi-IC) for 30′, and analyzed for binding of FITC-labeled ICs. The results showed that Bin cells again stained more brightly with FITC-OVA ICs than FoB cells (Fig. 4G). Pre-incubation with a blocking anti-CD21 antibody, or inactivation of complement prior to IC formation significantly decreased the intensity of FITC on Bin cells (Fig. 4G). These results show that Bin cells IC capture is dependent on CD21 and complement, and that this binding mechanism accounts for most if not all of the difference between Bin cells and FoBs in this respect.

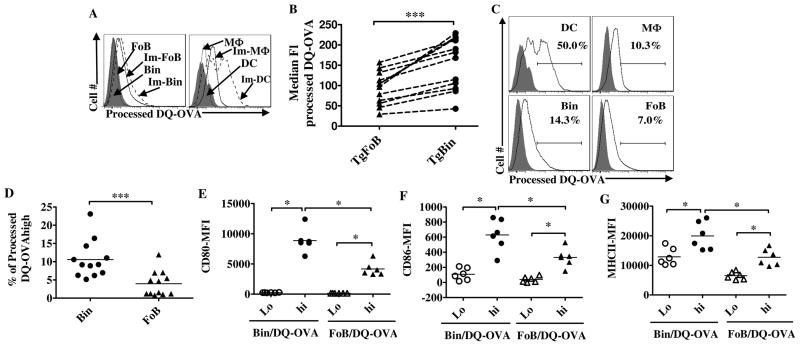

Although IC capture by B cells has been reported in some cases to lead to antigen processing and presentation in vitro (61, 64–67), the extent to which this occurs physiologically remains unclear (68–69). To test whether Bin cells are actually able to process the captured ICs we carried out footpad immunization experiments using the antigen DQ-OVA (Molecular Probes), a BODIPY FL dye-highly conjugated, self-quenched protein which has been used extensively for antigen presentation studies because it fluoresces brightly only after proteolysis in the endolysosomal compartment (69). As shown in Figure 5A, Bin cells from immunized PLNs show a higher intensity of processed DQ-OVA compared to FoB cells, although, not unexpectedly, less than dendritic cells. The entire population of Bin cells showed a small but significant increase in md.f.i. after exposure to antigen compared to FoBs (154±63 on Bin vs.93±40 on FoB, p=0.0005) (Fig. 5B) and a higher percentage of Bin cells in all LNs examined displayed high fluorescent intensity for processed DQ-OVA, in the same gate as high-processing dendritic cells, compared to FoBs (10.5±5% in Bin vs. 4± 3.5% in FoB, p=0.0005) (Fig. 5C,5D). Thus, Bin cells can capture non-cognate antigen via CD21-IC binding, as well as process it at a higher efficiency than FoB cells. Strikingly, DQ-OVA-hi, but not DQ-OVA-lo Bin and FoB cells harvested from immunized mice as early as 20 hrs after immunization showed significant upregulation of CD80, CD86 and MHCII (Fig. 5E–G). And again, Bin cells displayed higher levels of expression of these markers compared to FoB cells (Fig. 5E–G). Combined with the higher fraction of DQ-OVA-processing cells in the Bin compartment, and the evidence described above of Bin cells’ enhanced T costimulatory ability, these results suggest that Bin cells represent the major subset of B cells with CD4+ T cell activation potential in the early stages of the immune response in inflammatory conditions.

Figure 5. Antigen capture and processing by Bin cells.

A. TNFtg mice were footpad-immunized with DQ-OVA in CFA, and 20h later analyzed for processing of antigen (processed DQ-OVA Ex/Em: 505/515nm, FITC channel in LSRII). Representative histogram plots show comparison of FITC intensity between CD19+ FoB and Bin cells (left), and between CD19−B220+CD11C+ MHCIIhigh dendritic cells (DC) and CD19−CD11C−CD11b+ macrophages (Mφ) (right) in unimmunized (dotted and shaded lines) and immunized (solid and dashed lines) PLNs. B. Pair-wise comparison of the median fluorescent intensity of processed DQ-OVA on the surface of B cell subsets from immunized TNFtg PLNs. C. Representative plots showing gating for bright-positive cells for processed DQ-OVA based on DC profiles (top left), shaded histograms are the same cell subset from contralateral PLN. D. Pair-wise comparison of the percentages of antigen presenting cell subsets bright-positive for processed DQ-OVA in immunized TNFtg PLNs. E, Fand G. Intensity of CD80, CD86 and MHCII on DQ-OVA hi and DQ-OVA lo fraction of Bin and FoB cells 20h after immunization as determined by flow cytometry. B and D; combined results from four independent experiments (n=12). E–G; combined results from 2 independent experiments (n=6). *** p<0.001, * p<0.05, two-tailed Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test.

Discussion

The scale, specificity and timing of accumulation of Bin cells in LNs draining arthritic joints of TNFtg mice, their involvement in the histological and functional node alterations that accompany the onset of arthritic flares and the unexpected effectiveness of B cell depletion therapy in this model strongly implicate this new B cell population in the pathogenetic process (42–43). In the studies presented here, we set out therefore to characterize the origin and potential function of Bin cells in TNFtg mice. Our results not only contribute to clarify the picture regarding the original findings in TNFtg mice, but also extend their relevance to the more general and so far incompletely understood effects of inflammation on B cell responses.

The differentiation of Bin cells from adoptively transferred normal FoB cells clearly indicates that Bin cells are neither a distinct lineage, nor belong to the transitional/precursors subsets found in the mouse spleen with which they share some phenotypic features. Consistent with previous studies demonstrating the recruitment of non-dividing naïve lymphocytes into inflamed lymph nodes (59), we also showed that normal FoB cells are preferentially recruited to the LN draining arthritic joints in TNFtg mice, where they rapidly complete their phenotypic transition to Bin cells. Together with our observation that Bin cells are induced in draining LNs by adjuvant-only injections, these data suggest that in TNFtg mice the pro-inflammatory LN microenvironment is primarily responsible for both B cell accumulation from the circulating pool and for the generation of Bin cells. What specific signals mediate this phenotypic transition remain to be determined, but the close correlation between the fraction of endogenous Bin cells with the rate of differentiation of adoptively transferred FoB cells into Bins clearly indicates that the effect is microenvironmental, specific and quantitative.

The heretofore unnoticed appearance of Bin phenotype cells after immunization or adjuvant injection in normal LNs is consistent with the inducing factor(s) not being restricted to arthritis, but representing more general inflammatory signals present in reactive LNs. The relationship between inflammation and B cell function has been the focus of significant interest because of its implications for normal immune responses, the onset and amplification of autoimmune states, and the design of novel immune modulators and adjuvants (32, 35, 70). Inflammatory signals can have significant effects on B cell development and have been shown to affect peripheral B cell homeostasis by modulating BCR repertoire and selection/tolerance (33–34, 36). In addition, B cells can have active roles in regulating inflammatory states by their ability to secrete pro- or anti-inflammatory cytokines, and to influence T cell subset differentiation (7, 29, 48, 71–74).

Less well characterized are the direct effects of inflammation on B lymphocyte activation. Our results show that the inflammation-inducible Bin state corresponds to a heightened ability by B cells to capture and process ICs and to display GC and costimulatory markers. Although we cannot discriminate at this stage between increased Bin cell entrance into GCs, vs. higher proliferation, survival or persistence in the compartment, our findings indicate that these cells participate in the GC reaction more actively than FoBs. Also, together with the IC capture data, these observations point to a specific role of CD21 in this process.

CD21 expression on B cells has been shown to play a critical role in antibody responses to T-dependent antigens (50, 75) and to provide a cognate antigen-independent signal required for GC B cell survival (76). C3d (the C component ligand for CD21) can function as a molecular adjuvant, and its attachment to a foreign antigen is 100-fold more effective than CFA in lowering the threshold for activation of an adaptive immune response, and this augmentation is CD21-dependent (60).

RA patients also display significant alterations of both peripheral blood and lymphoid organ B cell subset composition which are reversible by anti-inflammatory therapy (77–78), although it is unknown at this stage whether any human Bin-equivalent population exists. However, a subset of RA patients have been reported to harbor a population of anergic, autoreactive CD21neg/low B cells, which suggests that CD21 downregulation may contribute to tolerance in some situations (79). Paradoxically, however, excess CD21 ligation can also inhibit B cell activation by depleting key kinases from the BCR complex (80), and absence of CD21 exacerbates autoimmunity in lpr mice (81), suggestive of a regulatory role during activation. CD21 has also been implicated in the shuttling of antigen, from dendritic cells and macrophages to follicular dendritic cells in the follicles, and by B cells both in the spleen and in LNs (26, 82–83); reviewed in (84). This antigen transport activity has been shown to be crucial for the development of effective functional humoral responses as well (76, 84). Thus, CD21 plays multi-faceted and context-dependent roles during B cell activation.

Bin cells share some phenotype similarities with B cell populations with regulatory functions (B10 and B-reg cells) identified in various inflammation and autoimmunity models (45–48, 54, 72, 74, 85–86, 87 ). Although we have been unable so far to detect significant secretion of IL10 or other cytokines by Bin cells in vitro (42), it is interesting to speculate that Bin cells, arising early during inflammation, may represent the originating population for these regulatory subsets, thus explaining their phenotypic features.

Our data suggest that upregulation of CD21 as part of the Bin phenotype by both normal and TNFtg B cells results in enhanced antigen capture and processing potential, and may contribute to T cell stimulation and to increased Bin cell involvement in the GC reaction. We would hypothesize therefore that Bin differentiation may be part of the physiological response to inflammation, aiming to generate an expanded local cohort of B cells poised for efficient activation. Furthermore, increased antigen processing ability and expression of costimulatory molecules already within one day of immunization is suggestive of non-cognate antigen presentation, and thus that Bin differentiation might also support an early wave of priming and activation of antigen-specific T cells before cognate B cell clones become sufficiently expanded.

Non-cognate antigen uptake and presentation by B cells has been previously demonstrated in a number of experimental systems, but their physiological relevance is unclear and the issue remains theoretically controversial (61, 64–67). Although our data are intriguingly consistent with this possibility, a formal test of the hypothesis will require detailed analyses of the dynamics and timing of Bin differentiation, antigen capture and processing, triggering, and activation, their effects on T cell activation in the context of normal immune responses, together with a genetic dissection of the role of CD21 and BCR specificity and complement in the process. If confirmed, this may provide new insights into effective mechanisms to enhance the immune response, e.g. to vaccination.

The picture differs in chronic inflammation, as is the case of the TNFtg mice, where Bin differentiation may on the other hand play a pathogenetic role. The persistent presence of a large pool of B cells poised for activation and potentially capable of non-cognate antigen presentation may lead to an increased risk of tolerance breakdown, and may contribute to the established correlation between local chronic inflammation and subsequent development of autoimmunity (17–19). Even when antigen-specific autoimmunity is not apparent, as is the case of TNFtg mice (though the issue may warrant revisiting in light of these and our previous findings, particularly in older animals), Bin cells may display aberrant behavior upon specific triggering, such as mobilization from the follicles, sinusoidal space invasion and LN histological and functional disruption, that in themselves may contribute to disease exacerbation by interfering with other homeostatic processes (e.g. lymphatic drainage) (42–43). In these instances, specific inhibition of the signals involved in Bin differentiation or their later mobilization within the LN may provide the basis for new therapeutic strategies to locally prevent or control arthritis progression and flare without the undesirable effects of systemic immunosuppression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. Jen Anolik, Edith Lord, Andrea Sant, Jim Miller, Alexandra Livingstone, Deborah Fowell and Lianping Xing and their labs for advice, protocols and reagents; to the University of Rochester Flow Cytometry Core facility and the Center for Vaccine Biology and Immunology cell sorting facility for expert technical support. This work was supported by NIH grants AI78907, AR54041 and AR61307.

Abbreviations

- LN

lymph node

- ALN

axillary LN

- Bin

B cells in inflamed nodes

- BLN

brachial LN

- FoB

follicular B cells

- GC

germinal center

- IC

immune complex

- md.f.i

median fluorescence intensity

- MLN

mesenteric LN

- PLN

popliteal LN

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- TFH

T follicular helper

- TNFtg

TNFα-transgenic

- WT

wild-type

- Hi-IC

Immune complex containing heat inactivated serum

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH grants RO1 AR056702 and P01 AI078907. FA is supported by NIH grant R25GM064133 “Resource in Education in Microbiology and Immunology”.

References

- 1.Bouaziz JD, Yanaba K, Venturi GM, Wang Y, Tisch RM, Poe JC, Tedder TF. Therapeutic B cell depletion impairs adaptive and autoreactive CD4+ T cell activation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20878–20883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709205105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu CY, Rodriguez-Pinto D, Du W, Ahuja A, Henegariu O, Wong FS, Shlomchik MJ, Wen L. Treatment with CD20-specific antibody prevents and reverses autoimmune diabetes in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3857–3867. doi: 10.1172/JCI32405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Neill SK, Glant TT, Finnegan A. The role of B cells in animal models of rheumatoid arthritis. Front Biosci. 2007;12:1722–1736. doi: 10.2741/2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serreze DV, Fleming SA, Chapman HD, Richard SD, Leiter EH, Tisch RM. B lymphocytes are critical antigen-presenting cells for the initiation of T cell-mediated autoimmune diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 1998;161:3912–3918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan OT, Hannum LG, Haberman AM, Madaio MP, Shlomchik MJ. A novel mouse with B cells but lacking serum antibody reveals an antibody-independent role for B cells in murine lupus. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1639–1648. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.10.1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krzysiek R, Lefevre EA, Zou W, Foussat A, Bernard J, Portier A, Galanaud P, Richard Y. Antigen receptor engagement selectively induces macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha (MIP-1 alpha) and MIP-1 beta chemokine production in human B cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:4455–4463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris DP, Haynes L, Sayles PC, Duso DK, Eaton SM, Lepak NM, Johnson LL, Swain SL, Lund FE. Reciprocal regulation of polarized cytokine production by effector B and T cells. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:475–482. doi: 10.1038/82717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lund FE. Cytokine-producing B lymphocytes-key regulators of immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:332–338. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cambridge G, Leandro MJ, Edwards JC, Ehrenstein MR, Salden M, Bodman-Smith M, Webster AD. Serologic changes following B lymphocyte depletion therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2146–2154. doi: 10.1002/art.11181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Papadopoulos NG, Tsiaousis GZ, Pavlitou-Tsiontsi A, Giannakou A, Galanopoulou VK. Does the presence of anti-CCP autoantibodies and their serum levels influence the severity and activity in rheumatoid arthritis patients? Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2008;34:11–15. doi: 10.1007/s12016-007-8018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mandik-Nayak L, Ridge N, Fields M, Park AY, Erikson J. Role of B cells in systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:639–645. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kramm H, Hansen KE, Gowing E, Bridges A. Successful therapy of rheumatoid arthritis with rituximab: renewed interest in the role of B cells in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2004;10:28–32. doi: 10.1097/01.rhu.0000111316.59676.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen SB, Emery P, Greenwald MW, Dougados M, Furie RA, Genovese MC, Keystone EC, Loveless JE, Burmester GR, Cravets MW, Hessey EW, Shaw T, Totoritis MC. Rituximab for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: Results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial evaluating primary efficacy and safety at twenty-four weeks. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2793–2806. doi: 10.1002/art.22025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keystone E, Emery P, Peterfy CG, Tak PP, Cohen S, Genovese MC, Dougados M, Burmester GR, Greenwald M, Kvien TK, Williams S, Hagerty D, Cravets MW, Shaw T. Rituximab inhibits structural joint damage in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitor therapies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:216–221. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.085787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leandro MJ, de la Torre I. Translational Mini-Review Series on B Cell-Directed Therapies: The pathogenic role of B cells in autoantibody-associated autoimmune diseases--lessons from B cell-depletion therapy. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;157:191–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03978.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Townsend MJ, Monroe JG, Chan AC. B-cell targeted therapies in human autoimmune diseases: an updated perspective. Immunol Rev. 2010;237:264–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flavell RA. The relationship of inflammation and initiation of autoimmune disease: role of TNF super family members. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2002;266:1–9. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-04700-2_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munoz LE, Janko C, Schulze C, Schorn C, Sarter K, Schett G, Herrmann M. Autoimmunity and chronic inflammation - two clearance-related steps in the etiopathogenesis of SLE. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;10:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neurath MF, Finotto S. IL-6 signaling in autoimmunity, chronic inflammation and inflammation-associated cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2011;22:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kratz A, Campos-Neto A, Hanson MS, Ruddle NH. Chronic inflammation caused by lymphotoxin is lymphoid neogenesis. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1461–1472. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Satoh M, Richards HB, Shaheen VM, Yoshida H, Shaw M, Naim JO, Wooley PH, Reeves WH. Widespread susceptibility among inbred mouse strains to the induction of lupus autoantibodies by pristane. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;121:399–405. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calvani N, Caricchio R, Tucci M, Sobel ES, Silvestris F, Tartaglia P, Richards HB. Induction of apoptosis by the hydrocarbon oil pristane: implications for pristane-induced lupus. J Immunol. 2005;175:4777–4782. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young CL, Adamson TC, 3rd, Vaughan JH, Fox RI. Immunohistologic characterization of synovial membrane lymphocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:32–39. doi: 10.1002/art.1780270106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schroder AE, Greiner A, Seyfert C, Berek C. Differentiation of B cells in the nonlymphoid tissue of the synovial membrane of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:221–225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gregorio A, Gambini C, Gerloni V, Parafioriti A, Sormani MP, Gregorio S, De Marco G, Rossi F, Martini A, Gattorno M. Lymphoid neogenesis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis correlates with ANA positivity and plasma cells infiltration. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:308–313. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferguson AR, Youd ME, Corley RB. Marginal zone B cells transport and deposit IgM-containing immune complexes onto follicular dendritic cells. Int Immunol. 2004;16:1411–1422. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelly-Scumpia KM, Scumpia PO, Weinstein JS, Delano MJ, Cuenca AG, Nacionales DC, Wynn JL, Lee PY, Kumagai Y, Efron PA, Akira S, Wasserfall C, Atkinson MA, Moldawer LL. B cells enhance early innate immune responses during bacterial sepsis. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1673–1682. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gavanescu I, Benoist C, Mathis D. B cells are required for Aire-deficient mice to develop multi-organ autoinflammation: A therapeutic approach for APECED patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13009–13014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806874105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lund FE, Randall TD. Effector and regulatory B cells: modulators of CD4(+) T cell immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:236–247. doi: 10.1038/nri2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anolik JH, Looney RJ, Lund FE, Randall TD, Sanz I. Insights into the heterogeneity of human B cells: diverse functions, roles in autoimmunity, and use as therapeutic targets. Immunol Res. 2009;45:144–158. doi: 10.1007/s12026-009-8096-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagaoka H, Gonzalez-Aseguinolaza G, Tsuji M, Nussenzweig MC. Immunization and infection change the number of recombination activating gene (RAG)-expressing B cells in the periphery by altering immature lymphocyte production. J Exp Med. 2000;191:2113–2120. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.12.2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ueda Y, Kondo M, Kelsoe G. Inflammation and the reciprocal production of granulocytes and lymphocytes in bone marrow. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1771–1780. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tortola L, Yadava K, Bachmann MF, Muller C, Kisielow J, Kopf M. IL-21 induces death of marginal zone B cells during chronic inflammation. Blood. 2010;116:5200–5207. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-284547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Goer de Herve MG, Durali D, Dembele B, Giuliani M, Tran TA, Azzarone B, Eid P, Tardieu M, Delfraissy JF, Taoufik Y. Interferon-alpha triggers B cell effector 1 (Be1) commitment. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ueda Y, Yang K, Foster SJ, Kondo M, Kelsoe G. Inflammation controls B lymphopoiesis by regulating chemokine CXCL12 expression. J Exp Med. 2004;199:47–58. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meyer-Bahlburg A, Andrews SF, Yu KO, Porcelli SA, Rawlings DJ. Characterization of a late transitional B cell population highly sensitive to BAFF-mediated homeostatic proliferation. J Exp Med. 2008;205:155–168. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cain D, Kondo M, Chen H, Kelsoe G. Effects of acute and chronic inflammation on B-cell development and differentiation. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:266–277. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keffer J, Probert L, Cazlaris H, Georgopoulos S, Kaslaris E, Kioussis D, Kollias G. Transgenic mice expressing human tumour necrosis factor: a predictive genetic model of arthritis. EMBO J. 1991;10:4025–4031. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04978.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li P, Schwarz EM. The TNF-alpha transgenic mouse model of inflammatory arthritis. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2003;25:19–33. doi: 10.1007/s00281-003-0125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Proulx ST, Kwok E, You Z, Beck CA, Shealy DJ, Ritchlin CT, Boyce BF, Xing L, Schwarz EM. MRI and quantification of draining lymph node function in inflammatory arthritis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1117:106–123. doi: 10.1196/annals.1402.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Proulx ST, Kwok E, You Z, Papuga MO, Beck CA, Shealy DJ, Ritchlin CT, Awad HA, Boyce BF, Xing L, Schwarz EM. Longitudinal assessment of synovial, lymph node, and bone volumes in inflammatory arthritis in mice by in vivo magnetic resonance imaging and microfocal computed tomography. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:4024–4037. doi: 10.1002/art.23128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li J, Kuzin I, Moshkani S, Proulx ST, Xing L, Skrombolas D, Dunn R, Sanz I, Schwarz EM, Bottaro A. Expanded CD23(+)/CD21(hi) B cells in inflamed lymph nodes are associated with the onset of inflammatory-erosive arthritis in TNF-transgenic mice and are targets of anti-CD20 therapy. J Immunol. 2010;184:6142–6150. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li J, Zhou Q, Wood R, Kuzin I, Bottaro A, Ritchlin C, Xing L, Schwarz E. CD23+/CD21hi B cell translocation and ipsilateral lymph node collapse is associated with asymmetric arthritic flare in TNF-Tg mice. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R138. doi: 10.1186/ar3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Allman D, Pillai S. Peripheral B cell subsets. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Evans JG, Chavez-Rueda KA, Eddaoudi A, Meyer-Bahlburg A, Rawlings DJ, Ehrenstein MR, Mauri C. Novel suppressive function of transitional 2 B cells in experimental arthritis. J Immunol. 2007;178:7868–7878. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mauri C, Gray D, Mushtaq N, Londei M. Prevention of arthritis by interleukin 10-producing B cells. J Exp Med. 2003;197:489–501. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mizoguchi A, Mizoguchi E, Takedatsu H, Blumberg RS, Bhan AK. Chronic intestinal inflammatory condition generates IL-10-producing regulatory B cell subset characterized by CD1d upregulation. Immunity. 2002;16:219–230. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00274-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carter NA, Vasconcellos R, Rosser EC, Tulone C, Munoz-Suano A, Kamanaka M, Ehrenstein MR, Flavell RA, Mauri C. Mice lacking endogenous IL-10-producing regulatory B cells develop exacerbated disease and present with an increased frequency of Th1/Th17 but a decrease in regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2011;186:5569–5579. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brossay L, Jullien D, Cardell S, Sydora BC, Burdin N, Modlin RL, Kronenberg M. Mouse CD1 is mainly expressed on hemopoietic-derived cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:1216–1224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heyman B, Wiersma EJ, Kinoshita T. In vivo inhibition of the antibody response by a complement receptor-specific monoclonal antibody. J Exp Med. 1990;172:665–668. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.2.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cherukuri A, Cheng PC, Sohn HW, Pierce SK. The CD19/CD21 complex functions to prolong B cell antigen receptor signaling from lipid rafts. Immunity. 2001;14:169–179. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lyubchenko T, dal Porto J, Cambier JC, Holers VM. Coligation of the B cell receptor with complement receptor type 2 (CR2/CD21) using its natural ligand C3dg: activation without engagement of an inhibitory signaling pathway. J Immunol. 2005;174:3264–3272. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fearon DT, Carroll MC. Regulation of B lymphocyte responses to foreign and self-antigens by the CD19/CD21 complex. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:393–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mauri C, Ehrenstein MR. The ‘short’ history of regulatory B cells. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Swenson ES, Price JG, Brazelton T, Krause DS. Limitations of green fluorescent protein as a cell lineage marker. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2593–2600. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barnden MJ, Allison J, Heath WR, Carbone FR. Defective TCR expression in transgenic mice constructed using cDNA-based alpha- and beta-chain genes under the control of heterologous regulatory elements. Immunol Cell Biol. 1998;76:34–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.1998.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marusic-Galesic S, Pavelic K, Pokric B. Cellular immune response to the antigen administered as an immune complex. Immunology. 1991;72:526–531. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.von Andrian UH, Mempel TR. Homing and cellular traffic in lymph nodes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:867–878. doi: 10.1038/nri1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Soderberg KA, Payne GW, Sato A, Medzhitov R, Segal SS, Iwasaki A. Innate control of adaptive immunity via remodeling of lymph node feed arteriole. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16315–16320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506190102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dempsey PW, Allison ME, Akkaraju S, Goodnow CC, Fearon DT. C3d of complement as a molecular adjuvant: bridging innate and acquired immunity. Science. 1996;271:348–350. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arvieux J, Yssel H, Colomb MG. Antigen-bound C3b and C4b enhance antigen-presenting cell function in activation of human T-cell clones. Immunology. 1988;65:229–235. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thomas WR, Edwards AJ, Watkins MC, Asherson GL. Distribution of immunogenic cells after painting with the contact sensitizers fluorescein isothiocyanate and oxazolone. Different sensitizers form immunogenic complexes with different cell populations. Immunology. 1980;39:21–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kinoshita T, Takeda J, Hong K, Kozono H, Sakai H, Inoue K. Monoclonal antibodies to mouse complement receptor type 1 (CR1). Their use in a distribution study showing that mouse erythrocytes and platelets are CR1-negative. J Immunol. 1988;140:3066–3072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thornton BP, Vetvicka V, Ross GD. Natural antibody and complement-mediated antigen processing and presentation by B lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1994;152:1727–1737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jacquier-Sarlin MR, Gabert FM, Villiers MB, Colomb MG. Modulation of antigen processing and presentation by covalently linked complement C3b fragment. Immunology. 1995;84:164–170. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boackle SA, Morris MA, Holers VM, Karp DR. Complement opsonization is required for presentation of immune complexes by resting peripheral blood B cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:6537–6543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hess MW, Schwendinger MG, Eskelinen EL, Pfaller K, Pavelka M, Dierich MP, Prodinger WM. Tracing uptake of C3dg-conjugated antigen into B cells via complement receptor type 2 (CR2, CD21) Blood. 2000;95:2617–2623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Byersdorfer CA, Dipaolo RJ, Petzold SJ, Unanue ER. Following immunization antigen becomes concentrated in a limited number of APCs including B cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:6627–6634. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.6627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.de Jong JM, Schuurhuis DH, Ioan-Facsinay A, Welling MM, Camps MG, van der Voort EI, Huizinga TW, Ossendorp F, Verbeek JS, Toes RE. Dendritic cells, but not macrophages or B cells, activate major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted CD4+ T cells upon immune-complex uptake in vivo. Immunology. 2006;119:499–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02464.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liang B, Eaton-Bassiri A, Bugelski PJ. B cells and beyond: therapeutic opportunities targeting inflammation. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2007;6:142–149. doi: 10.2174/187152807781696473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Harris DP, Goodrich S, Gerth AJ, Peng SL, Lund FE. Regulation of IFN-gamma production by B effector 1 cells: essential roles for T-bet and the IFN-gamma receptor. J Immunol. 2005;174:6781–6790. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.DiLillo DJ, Matsushita T, Tedder TF. B10 cells and regulatory B cells balance immune responses during inflammation, autoimmunity, and cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1183:38–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Scapini P, Lamagna C, Hu Y, Lee K, Tang Q, Defranco AL, Lowell CA. B cell-derived IL-10 suppresses inflammatory disease in Lyn-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107913108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Amu S, Saunders SP, Kronenberg M, Mangan NE, Atzberger A, Fallon PG. Regulatory B cells prevent and reverse allergic airway inflammation via FoxP3-positive T regulatory cells in a murine model. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:1114–1124. e1118. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Croix DA, Ahearn JM, Rosengard AM, Han S, Kelsoe G, Ma M, Carroll MC. Antibody response to a T-dependent antigen requires B cell expression of complement receptors. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1857–1864. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fischer MB, Goerg S, Shen L, Prodeus AP, Goodnow CC, Kelsoe G, Carroll MC. Dependence of germinal center B cells on expression of CD21/CD35 for survival. Science. 1998;280:582–585. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5363.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Anolik JH, Ravikumar R, Barnard J, Owen T, Almudevar A, Milner EC, Miller CH, Dutcher PO, Hadley JA, Sanz I. Cutting edge: anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in rheumatoid arthritis inhibits memory B lymphocytes via effects on lymphoid germinal centers and follicular dendritic cell networks. J Immunol. 2008;180:688–692. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Souto-Carneiro MM, Mahadevan V, Takada K, Fritsch-Stork R, Nanki T, Brown M, Fleisher TA, Wilson M, Goldbach-Mansky R, Lipsky PE. Alterations in peripheral blood memory B cells in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis are dependent on the action of tumour necrosis factor. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R84. doi: 10.1186/ar2718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Isnardi I, Ng YS, Menard L, Meyers G, Saadoun D, Srdanovic I, Samuels J, Berman J, Buckner JH, Cunningham-Rundles C, Meffre E. Complement receptor 2/CD21-human naive B cells contain mostly autoreactive unresponsive clones. Blood. 2010;115:5026–5036. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-243071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chakravarty L, Zabel MD, Weis JJ, Weis JH. Depletion of Lyn kinase from the BCR complex and inhibition of B cell activation by excess CD21 ligation. Int Immunol. 2002;14:139–146. doi: 10.1093/intimm/14.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Prodeus AP, Goerg S, Shen LM, Pozdnyakova OO, Chu L, Alicot EM, Goodnow CC, Carroll MC. A critical role for complement in maintenance of self-tolerance. Immunity. 1998;9:721–731. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80669-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Phan TG, Grigorova I, Okada T, Cyster JG. Subcapsular encounter and complement-dependent transport of immune complexes by lymph node B cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:992–1000. doi: 10.1038/ni1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Carrasco YR, Batista FD. B cells acquire particulate antigen in a macrophage-rich area at the boundary between the follicle and the subcapsular sinus of the lymph node. Immunity. 2007;27:160–171. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gonzalez SF, Lukacs-Kornek V, Kuligowski MP, Pitcher LA, Degn SE, Turley SJ, Carroll MC. Complement-dependent transport of antigen into B cell follicles. J Immunol. 2010;185:2659–2664. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yanaba K, Bouaziz JD, Haas KM, Poe JC, Fujimoto M, Tedder TF. A regulatory B cell subset with a unique CD1dhiCD5+ phenotype controls T cell-dependent inflammatory responses. Immunity. 2008;28:639–650. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Matsushita T, Yanaba K, Bouaziz JD, Fujimoto M, Tedder TF. Regulatory B cells inhibit EAE initiation in mice while other B cells promote disease progression. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3420–3430. doi: 10.1172/JCI36030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mizoguchi A, Bhan AK. A case for regulatory B cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:705–710. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.