Abstract

The role of Th17 cells in cancer patients remains unclear and controversial. In this study, we have analyzed the phenotype of in vitro primed Th17 cells and further characterized their function on the basis of CCR4 and CCR6 expression. We show a novel function for a subset of IL-17 secreting CD4+ T cells, namely CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells. When cultured together, CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells suppressed the lytic function, proliferation and cytokine secretion of both antigen specific and CD3/CD28/CD2 stimulated autologous CD8+ T cells. In contrast, CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ T cells, which also secrete IL-17, did not affect the CD8+ T cells. Suppression of CD8+ T cells by CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells was partially dependent on TGF-β, since neutralization of TGF-β in cocultures reversed their suppressor function. In addition, we also found an increase in the frequency of CCR4+CCR6+, but not CCR4negCCR6+ Th17 cells in peripheral blood of HCC patients. Our study not only underlies the importance of analysis of subsets within Th17 cells to understand their function, but also suggests Th17 cells as yet another immune evasion mechanism in HCC. This has important implications when studying the mechanisms of carcinogenesis as well as designing effective immunotherapy protocols for patients with cancer.

Introduction

Th17 cells are a novel subset of CD4+ helper T cells that play an important role in pathogenesis of several inflammatory and autoimmune diseases (1). These cells secrete IL-17, a cytokine that can recruit and expand neutrophils through secretion of chemokines (2). It has been shown that mice deficient in IL-17 receptor are more susceptible to certain pathogens (3, 4). Recently, conflicting data have been reported on the role of Th17 cells in cancer (5–7). Increased frequencies of Th17 cells have been reported in patients with different types of tumors (8–11) although their exact role in cancer is still not clear.

The precise conditions for human Th17 cell development remain controversial. However, recent studies have demonstrated that TGF-β in combination with IL-1, IL-6 and IL-23 can induce the generation of Th17 cells from CD4+ memory T cells (1). Lack of a specific surface marker for Th17 cells causes difficulties in their isolation for direct ex vivo functional analysis. Human Th17 cells have been shown to express IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-22, IL-26, IFN-γ and their functions have been shown to be pivotal in the context of different autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis (12), asthma (13), rheumatoid arthritis (14), and inflammatory bowel disease (15).

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third-leading cause of death from cancer and the fifth most common malignancy worldwide (16). HCC is often diagnosed at an advanced stage when it is no longer amenable to curative therapies (17). Highly active drug-metabolizing pathways and multidrug resistance transporter proteins in tumor cells further diminish the efficacy of current therapeutic regimens for this cancer type. Alternative approaches are therefore needed to overcome these barriers to successful therapy and immunotherapy represents one possible option (18). A number of different immune suppressor mechanisms and cells have been identified in HCC including CD4+ Tregs, myeloid derived suppressor cells and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and PD-1 expression (19).

We have initially analyzed different cytokines in primary tumors from patients with HCC and observed high concentrations of IL-17 and IL-23 in primary tumor supernatants. Based on these findings, we further analyzed T cell responses and noticed a significantly increased frequency of IL-17 secreting CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood of HCC patients, which led us to investigate the biological function of these cells and particularly their effect on CD8+ T cells. In vitro generated Th17 cells suppressed proliferation and cytokine secretion of CD3/CD28/CD2 stimulated CD8+ T cells in vitro. Further separation of Th17 cells into CCR4negCCR6+ and CCR4+CCR6+ cell populations indicated that only IL-17 secreting CCR4+CCR6+Th17 but not CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ T cells suppressed proliferation and cytokine secretion of CD3/CD28/CD2 or antigen stimulated CD8+ T cells in vitro. Finally, we were able to demonstrate an increase in the frequency of the CCR4+CCR6+Th17 but not of CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ T cell population in patients with HCC. Taken together, all our data suggest that CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells represent another mechanism of immune evasion in HCC patients. These findings might have important implications in designing immunotherapy protocols.

Material and Methods

Patients and Healthy Donors

Blood samples were collected from patients with HCC seen at the Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Endocrinology, Hannover Medical School (Hannover, Germany). HCC was diagnosed according to the guidelines of the European Association for the Study of the Liver. No patient included in this study received a tumor specific therapy (incl. surgery, transarterial chemoembolisation, ablation or chemotherapy) at least 6 weeks prior to analysis of blood samples. Written consent was obtained from all patients before blood and tumor sampling, and the Ethics Committee of Hannover Medical School approved the study protocol. Clinical information on HCC patients is shown as Supplemental data.

Preparation of tumor supernatant

Single-cell suspensions of tumors obtained from surgery were prepared by mechanical dissociation and collagenase/dispase treatment for 45 to 60 minutes at 37°C (Roche Diagnostics). After digestion, the cells were cultured at 37°C overnight. The supernatants were harvested and tested for the indicated cytokines by commercially available ELISA: IL-6 (Immunotools), IL-10 (Immunotools), IL-12p70 (eBiosciences); IL-17A (eBiosciences), IL-23 (eBiosciences), VEGF (PeproTech), TNF-α (Immunotools), IFN-γ (Immunotools), TGF-β (eBiosciences).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry double staining for CD4 (DAKO, Carpinteria CA, cat #M3710, mouse monoclonal Ab, clone, 4B12 at 1:50 titer detected by DAB) and IL-17 (R&D Systems, Cat # AF-317-NA, affinity-purified goat, at 1:50 titer detected with Fast Red) was performed on formalin fixed, paraffin embedded tissue sections using Dako Env+ and Link+AP detection systems. Slides were deparaffinized with graded alcohols, and xylene, then subject to antigen retrieval for 30 minutes in a steamer with pH 9 Citrate retrieval buffer (DAKO) blocked with 1.5% H2O2 for 20 minutes, treated with protein block (Dako) for 20 minutes, then hybridized with the anti-CD4 antibody for 60 minutes at room temperature, followed with secondary antibody reagent (Envision+, Dako) for 20 minutes, and DAB for 10 minutes, then double block (Dako) for 10 minutes, and anti-IL17 antibody for 60 minutes at room temperature, followed by secondary antibody reagent (Link/LSAB+, Dako) for 15 minutes, with the addition of AP polymer for 15 minutes, and detection with Fast Red for 30 minutes. Slides were then dehydrated in graded alcohols, and xylene, and coverslipped. Antigens were detected singularly using the same protocol, as well as appropriate negative controls. Tonsil tissue was used as positive controls. Photomicrographs were with a Zeiss Axioplan 2ie microscope, 40X Plan Aprochromat objective with a color AxioCam HRc camera and Axiovision 4.7 software.

Th17 cell culture in vitro

CD4+ memory T cells were isolated from freshly obtained PBMC using Memory CD4+ T Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The enriched CD4+ memory T cells were cultured in human T cell medium (RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% human serum). CD4+ memory T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28/CD2 beads (Miltenyi Biotech) for 7 days in the presence of recombinant IL-1β (10 ng/ml), IL-6 (40 ng/ml), IL-23 (50 ng/ml), neutralizing anti-IL-4 (0.5 mg/ml) and anti-IFN-γ (5 mg/ml) (R&D Systems).

Cell isolation and sorting

Human PBMC were isolated from freshly obtained healthy donor blood by ficoll density gradient centrifugation (Biochrom AG). CD8+ T cells were sorted from the autologous PBMC as CD3+CD8+ cells. The purity of the cells was > 95% after sorting. CD4+IL-17+ were isolated from Th17 cell cultures using stimulation and staining reagents from the IL-17-Secretion Assay-Detection Kit (Miltenyi Biotec). In brief, in vitro cultured Th17 cells were stimulated with Cytostim. After 4 hours cells were first labeled with IL-17 catch reagent followed by another 45 minute incubation period at 37°C. Finally, cells were stained with an IL-17 detection antibody together with anti-CD4 (and anti-CCR4 and anti-CCR6 antibodies where indicated). CCR4+CCR6+Th17 and CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ T cells were sorted as CCR4+CCR6+ and CCR4negCCR6+ cells from CD4+IL-17+ population using a BD FACS Aria cell sorter system (Becton Dickinson). CD4+IL-17− cells were sorted in parallel as controls. For analysis of the effect of Th17 cells on antigen-specific T cell responses, CCR4+CCR6+ and CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ T cells were sorted from 7 days in vitro cultured CD4+ memory T cells using BD FACS Aria cell sorting system (Becton Dickinson).

Flow Cytometry Analysis

FACS acquisition was performed on LSR-II and results were analyzed with FlowJo Version 9.3.1.2 software (TreeStar Inc). FACS staining was done with the following antibodies: anti-CD4 (Miltenyi Biotech); anti-IL-17 (eBiosciences); anti-CD45RA, anti-CD45RO (Immunotools,); anti-CCR4, anti-CCR5, anti-CCR6, anti-IL23-receptor (R&D Systems); anti-CXCR3, anti-CD161, anti-IFN-γ and anti-Foxp3 (BD Biosciences). Anti-TGF-β (Biolegend) was used to stain membrane bound TGF-β. Isotype-matched antibody controls were used as indicated. For intracellular cytokine analysis, PBMC were stimulated with PMA/ionomycin in the presence of GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences) and intracellular cytokine staining was performed according to the manufacturers’ instruction.

Coculture assays

Sorted CD3+CD8+ T cells were cocultured with γ-irradiated autologous CCR4+CCR6+Th17, CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ or CD4+IL-17negT cells at different ratio in the presence of CD3/CD28/CD2 beads. Supernatants were collected after 48 hours and IFN-γ secretion was tested by IFN-γ ELISA (e-Biosciences). 72 hours after co-culture 3-H labeled thymidine was added and cells were incubated for additional 16 hours. CD8+ T cell proliferation was determined by measuring 3-H incorporation after 16 hours. IFN-γ secretion was tested by IFN-γ ELISA (e-Biosciences). For analysis of antigen-specific T cell responses, M1 peptide specific T cells were generated as previously described (20). Antigen-specific lysis was determined at an effector to target ratio of 5:1 in a standard 4-hour 51-Cr release assay in the presence or absence of autologous CCR4+CCR6+CD4+ and CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ T cells. In some experiments, indicated concentrations of anti-TGF-β (R&D System) were used to neutralize TGF-β, the corresponding isotype control was also used as indicated.

Statistical analysis

All the statistical analyses were based on two-tailed Student’s t test. All p values less than 0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

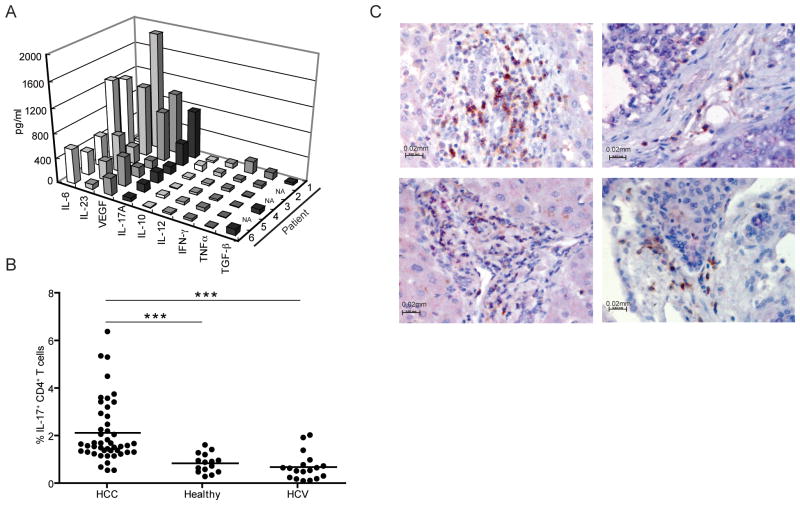

Supernatants from HCC tumor samples contain IL-17, IL-23, IL-6 and VEGF

Cytokines, which can induce both systemic and local immune suppression, can be secreted by tumors and tumor surrounding cells. We analyzed fresh viable tumor samples from 6 random HCC patients. No differences in the ratio of immune versus stroma cells were observed in the tissues analyzed. We tested HCC tumor supernatants for VEGF, TNF-α, TGF-β, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, IL-17A and IL-23. The predominant cytokines detected in the majority of HCC tumor supernatants were IL-17A, IL-23, IL-6 and VEGF (Figure 1A). This prompted us to look for IL-17 secreting CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood of HCC patients and healthy controls stimulated with PMA/ionomycin. The frequency of IL-17+CD4+ T cells was significantly increased in peripheral blood of HCC patients as compared to healthy donors and HCV patients (Figure 1B). Immunohistochemical analysis was performed to examine tumor infiltrating CD4+ T cells and revealed that the majority of CD4+ T cells co-expressed IL-17 with no preference for a specific location (intra/peritumoral) (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Evaluation of different cytokines and IL-17 secreting CD4+ T cells in HCC patients.

A- Tumor supernatant from HCC samples contains significant amounts of IL-17, IL-23, IL-6 and VEGF. Single-cell suspensions of tumors were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Supernatants were harvested and tested for different cytokines by ELISA.

B- Frequency of IL-17 secreting CD4+ T cells is increased in the peripheral blood of HCC patients. PBMC from healthy donors (n = 15), HCC (n = 46) or HCV (n=18) patients, were analyzed for IL-17 secreting CD4+ T cells. ***p<0.001.

C- CD4+ T cells in HCC co-express IL-17. Immunohistochemical detection of CD4 (brown-DAB) and IL-17 (red-Fast Red) in different HCC samples was performed. Scale bar equals 20 μm. Shown are the results of 4/5 different tumors analyzed.

IL-17 producing CD4+ T cells suppress CD8+ T cell function

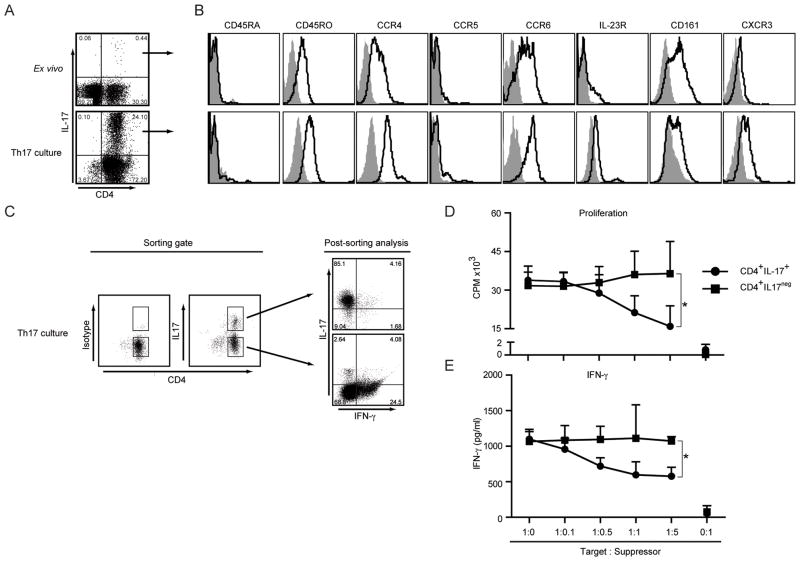

In order to obtain enough cells for functional experiments, sorted CD4+ memory T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28/CD2 beads in the presence of IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-23 cytokines, anti-IL-4 and anti-IFN-γ antibodies. As shown in Figure 2A, IL-17 secreting CD4+ T cells were expanded to more than 24% upon in vitro culture. Next the phenotype of in vitro primed and ex vivo isolated IL-17+CD4+ T cells were compared (Figure 2B). Both group of cells were CD45RA− and CD45RO+, expressed CCR4, CCR6, low levels of IL-23 receptor and CXCR3. They also expressed CD161, which has been suggested as an additional marker for Th17 cells (21, 22). In order to examine the possible function of these cells, we next isolated IL-17+ CD4+ T cells from in vitro cultures (Figure 2C) and co-incubated them with CD3/CD28/CD2 stimulated autologous CD8+ T cells at different cell ratios.

Figure 2. Isolation, Expansion and Characterization of CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells.

A- Frequency of IL-17 secreting CD4+ T cells in ex vivo PBMCs or in vitro cultured CD4+ memory T cells. Cells were stimulated with PMA/Ionomycin and stained for CD4 and intracellular IL-17. Result shown is representative of 6 independent experiments.

B- Characterization of CD4+IL-17+ T cells. FACS analysis of ex vivo isolated (top) and in vitro primed Th17 cells (bottom) for different surface markers (black lines) and isotype controls (filled histograms). Shown are representative histograms of 4 independent experiments.

C- Sorting of Th17 cells based on CD4 and IL-17 expression and post sorting analysis. In vitro primed Th17 cells were stimulated and sorted as described in Materials and Methods. CD4+IL-17+ and CD4+IL−17− cells were collected as shown. The sorted cell populations were restimulated with PMA/Ionomycin to determine IL-17 and IFN-γ secretion in parallel. Shown is representative dot plot of 3 independent experiments.

D and E- Sorted CD4+IL-17+Th17 or CD4+IL17neg T cells were γ-irradiated and co-cultured with autologous CD3+CD8+ T cells as described in Materials and Methods. Proliferation (D) and IFN-γ secretion (E) of CD8+ T cells are shown as the cumulative result of 3 independent experiments. *p<0.05.

As shown in Figure 2D, CD4+IL-17+ cells inhibited the proliferation of autologous CD8+ T cells in a dose dependent manner. There was a 14.2 ± 15.3%, 35.9 ± 8.72% and 51.1 ± 5.82% inhibition of T cell proliferation at CD8: Th17 cell ratios of 1:0.5, 1:1 and 1:5 respectively. In contrast, CD4+ IL-17neg T cells did not suppress the proliferation at any ratio tested. CD4+IL-17+ cells also reduced IFN-γ secretion by autologous CD8+ T cells, which was not observed when CD8+ T cell were co-incubated with CD4+ IL-17neg T cells (Figure 2E).

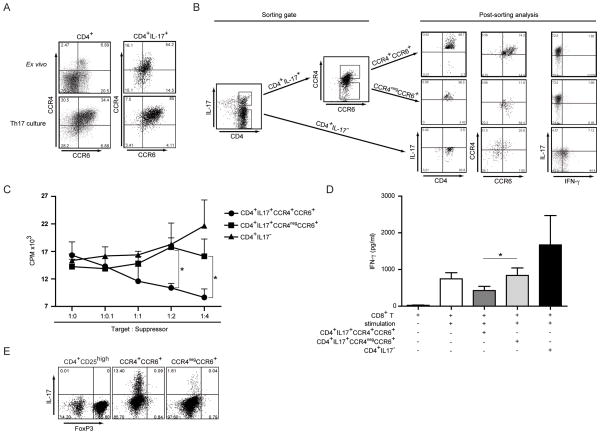

CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells suppress proliferation and IFN-γ production of autologous CD8+ T cells

Two distinct subpopulations of IL-17 producing T cells based on the expression of CCR4 and CCR6 have been recently identified (23). Therefore, we also analyzed the expression of CCR4 and CCR6 simultaneously on CD4+IL-17+ cells directly ex vivo and after in vitro priming. In vitro priming of Th17 cells increased the frequency of CCR4+CCR6+CD4+ T cells from 6.9 to 34.4 % and from 54.2 to 85% when CD4+IL-17+ cells were analyzed (Figure 3A). In parallel, the frequency of CCR4negCCR6+ decreased upon in vitro priming. Based on these findings we decided to sort CCR4+CCR6+Th17 and CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ and CD4+IL-17neg T cells from in vitro primed T cell cultures for our functional studies. For this, in vitro primed Th17 cultures were first stained with a bispecific IL-17+ capture antibody and IL-17+ cells were further separated into CCR4+CCR6+ and CCR4negCCR6+ populations (Figure 3B). Using this sorting strategy we were able to obtain greater than 96% pure T cell populations regarding IL-17 analysis and 74% pure cell populations regarding CCR4/CCR6 staining. Finally, we tested IL-17 and IFN-γ secretion from CCR4negCCR6+ and CCR4+CCR6+Th17 as well as CD4+IL-17neg T cells. While neither CCR4negCCR6+ nor CCR4+CCR6+Th17 stained positive for intracellular IFN-γ, 50 % of CD4+ T cells isolated from IL-17 negative cultures were IFN-γ positive (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. CCR4+CCR6+Th17, but not CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ T cells suppress autologous CD8+ T cell proliferation and cytokine secretion.

A- CCR4 and CCR6 expression on CD4+IL-17+ cells. Parallel CCR4 and CCR6 FACS analysis was performed on CD4+ T cells (left panel) or CD4+IL-17+ cells (right panel) from ex vivo PBMC or Th17 cultured in vitro. Shown are representative dot plots of 4 independent experiments.

B- Sorting of Th17 cells based on CCR4 and CCR6 expression and post sorting analysis. In vitro primed Th17 cells were stimulated and sorted according to CCR4 and CCR6 expression in the CD4+IL-17+ gate as described in Materials and Methods. CD4+IL-17neg cells were used as a control (left panel). Purified cell subpopulations were reanalyzed for CCR4/CCR6 expression and IL-17 expression. Cells were restimulated with PMA/Ionomycin to determine IL-17 and IFN-γ secretion in parallel. Shown is representative dot plot of 3 independent experiments.

C and D- Sorted CCR4+CCR6+Th17, CCR4negCCR6+CD4+ or CD4+IL-17neg T cells were cocultured with autologous CD3+CD8+ T cells as described in Materials and Methods. Proliferation (C) and IFN-γ secretion (D) of CD8+ T cells are shown as the cumulative result of 5 independent experiments. *p<0.05.

E- CCR4+CCR6+Th17 and CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ cells were sorted from in vitro primed Th17 culture, and tested for FoxP3 and IL-17 expression after restimulation with PMA/Ionomycin. CD4+CD25high cells were used as Foxp3 staining control and gates were set on Foxp3high cells. Shown is a representative dot plot of 3 independent experiments.

In order to investigate the potential effects of Th17 cells on CD8+ T cell responses, we co-incubated irradiated CCR4+CCR6+Th17 and CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ T cells at different ratios with CD3/CD28/CD2 stimulated autologous CD8+ T cells and analyzed IFN-γ release as well as proliferation of CD8+ T cells. As shown in Figure 3C, CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells inhibited the proliferation of autologous CD8+ T cells in a dose dependent manner. There was a 26.9 ± 23.5%, 30.9 ± 1.03% and 48.0 ± 15.11% inhibition of T cell proliferation at CD8: Th17 cell ratios of 1:1, 1:2 and 1:4 respectively. In contrast CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ T cells as well as CD4+IL17neg T cells did not suppress the proliferation at any ratio tested. CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells also reduced IFN-γ secretion by autologous CD8+ T cells, which was not observed when CD8+ T cell were co-incubated with CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ T cells or CD4+IL17neg T cells (Figures 3D). This inhibition of CD8+ T cell function was not due to Foxp3+ expression since similar levels of Foxp3 were seen in CCR4+CCR6+Th17 and CCR4negCCR6+Th17 cell subsets. In addition, Foxp3 staining was lower on both Th17 cell subsets than on CD4+CD25high nTregs. Similar findings have been previously described for activated CD4+ T cells without suppressor function (24).

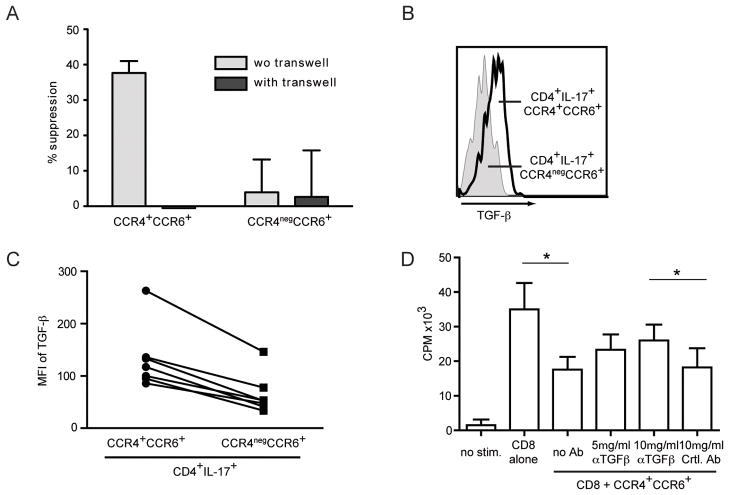

Suppression of CD8+ T cell responses by CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells is partly mediated by TGF-β

In order to understand how CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells suppress CD8+ T cell function, we repeated the co-culture experiment using a 0.4 μm permeable transwell plate. In the presence of transwell, CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells failed to inhibit CD8+ T cell function suggesting that cell-contact was needed (Figure 4A). TGF-β is a cytokine with profound inhibitory function, which can also exert its function when cell membrane bound (25). Therefore, we analyzed surface expression of TGF-β, which was higher on CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells than on CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ cells (Figures 4B and C). Next we co-incubated CD8+ T cells with CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells in the presence of anti-TGF-β and found that CCR4+CCR6+Th17 were less potent in inhibition of CD8+ T cell proliferation (Figure 4D). Similar results were observed for IFN-γ release by CD8+ T cells in the presence of anti-TGF-β (data not shown).

Figure 4. CCR4+CCR6+Th17 suppress autologous CD8+ T cells in a cell contact dependent manner and suppression is partly mediated by membrane bound TGF-β.

A- CCR4+CCR6+Th17 or CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ T cells were cocultured with autologous CD3+CD8+ T cells at a ratio of 5:1 with or without transwell and stimulated as described. IFN-γ secretion of CD8+ T cells was measured. Data shown is the cumulative result of 4 independent experiments (No suppression was seen when CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells and CD8+ T cells were separated by transwell).

B and C- CCR4+CCR6+Th17 and CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+T cells were sorted from in vitro cultured Th17 cells and stained for surface TGF-β. A representative FACS histogram (B) and the cumulative MFI for TGF-β (C) of 7 independent samples are shown.

D- Sorted and γ-irradiated CCR4+CCR6+Th17 were co-cultured with autologous CD3+CD8+ T cells at a ratio of 5:1 as described. TGF-β neutralizing antibody or corresponding isotype control antibody was added at the indicated concentrations. Data shown is the cumulative result of 5 independent experiments. *p<0.05.

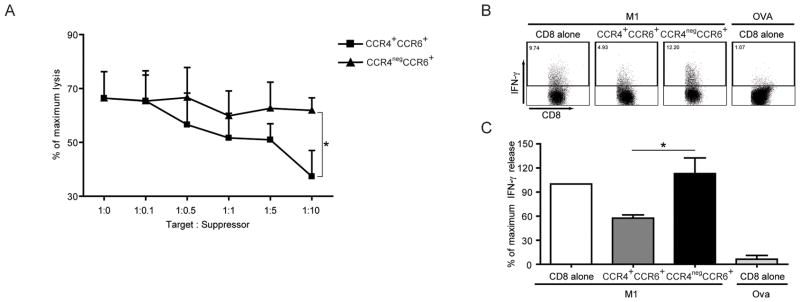

CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells suppress antigen-specific CD8+ T cell responses

Since antigen-specific lysis is one major feature of CD8+ T cells, we wanted to test the effect of CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells on peptide-specific CD8+ T cell responses. An influenza matrix peptide (M1) specific CD8+ T cell line was established as previously described (20) and M1-peptide specific T cells were incubated with γ-irradiated CCR4+CCR6+ or CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ T cells from autologous Th17 in vitro culture. Peptide-specific lysis was analyzed in a standard 4-hour cytotoxicity assay. As shown in Figure 5A, CCR4+CCR6+ but not CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ T cells suppressed antigen-specific lysis by CD8+ T cells in a dose dependent manner. Next, antigen-specific cytokine secretion by CD8+ T cells was analyzed. Again, CCR4+CCR6+Th17 but not CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ T cells suppressed IFN-γ secretion of M1-specific CD8+ T cells (Figures 5B & 5C).

Figure 5. CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells suppress lytic function and IFN-γ secretion of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells.

A- Peptide-specific T cells were cultured in the absence or presence of different ratios of CCR4+CCR6+ Th17 or CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ T cells in different ratios as indicated. After 1 hour, 51Cr labeled and peptide pulsed T2 cells were added at a ratio of 5:1 (E:T) and lysis was determined by standard 51Cr-release assay. Data shown is cumulative results from 4 independent experiments.

B and C- CCR4+CCR6+Th17 or CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+T cells were incubated with peptide stimulated antigen-specific T cells at a ratio of 5:1 and IFN-γ production was analyzed by intracellular staining. Data shown is one representative dot plot (B) and the cumulative results of 5 independent experiments (C). *p<0.05.

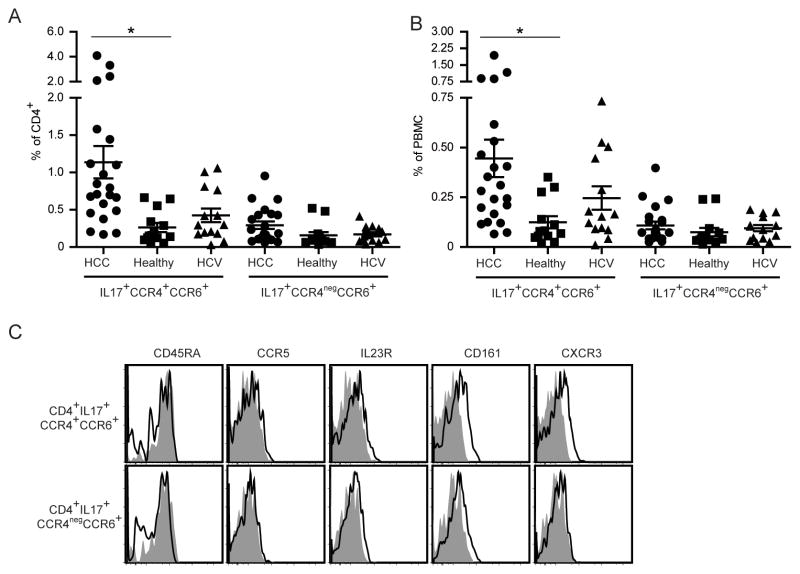

CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells analysis in peripheral blood of HCC patients

Our studies so far clearly indicated that only CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells but not CCR4negCCR6+IL-17+ CD4+ T cells suppress the function of CD8+ T cells. So we analyzed the frequency of both CCR4+CCR6+IL-17+CD4+ and CCR4negCCR6+IL-17+ CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood of patients with HCC, healthy controls and chronic HCV infection. The highest frequency of CCR4+CCR6+IL-17+ CD4+ T cells was detected in peripheral blood from patients with HCC (0.45 ± 0.09 % in PBMC and 1.14 ± 0.22 % in CD4+ T cells) followed by patients with chronic HCV infection (0.25 ± 0.06 % in PBMC and 0.42 ± 0.09 % in CD4+ T cells), who were used as a tumor-free patient control with chronic liver disease (Figures 6A and B). Next we examined the phenotype of CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells from patients with HCC and compared them with CCR4negCCR6+ IL-17+ CD4+ T cells. Relative CXCR3 and CD161 MFI values were slightly higher on CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells compared to CCR4negCCR6+ IL-17+ CD4+ T cells (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. Increased frequency of CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells in peripheral blood from patients with HCC.

A and B- Frequency of CCR4+CCR6+Th17 and CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ T cells. PBMC from HCC patients (n = 22), healthy donors (n = 13) and non-tumor chronic HCV infected patients (n = 14) were analyzed. The frequency of CCR4+CCR6+ and CCR4negCCR6+ cells within the CD4+ Foxp3neg (A) and within the Foxp3neg PBMC gate (B) is shown. *p<0.05.

C- CCR4+CCR6+Th17 and CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ T cells from HCC patients were stained for CD45RA, CCR5, IL23R, CD161 and CXCR3. Shown are representative dot plots of 8 different donors.

Discussion

Th17 cells are a novel subset of T helper cells that play a major role in tissue inflammation, protection against pathogens and autoimmune diseases. IL-17 elicits the production of a variety of pro-inflammatory cytokines including GM-CSF, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-23, which is also important for the differentiation, expansion and survival of Th17 cells (1). In this study, we have examined a subset of Th17 cells in more detail and demonstrate that CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells impair the function of CD8+ T cells. CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells but not CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ T cells inhibit the lytic function, cytokine secretion and proliferation of autologous antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. Interestingly, analysis of CD4+ T cells and Th17 related/dependent cytokines revealed an increase of Th17 subset in peripheral blood from patients with HCC as well as increased levels of IL-17 and IL-23 in primary tumors suggesting a novel immune evasion mechanism in this patient population.

Immune responses have been shown to be of pivotal importance for the outcome of patients with HCC. We have previously demonstrated that significant gene expression changes occur in the liver microenvironment of patients with HCC and accompanying venous metastases. Mainly inflammation/immune responses contributed to this expression signature (27). Recently, high neutrophil infiltration of HCC has been shown to be a powerful predictor of disease progression and poor overall survival after tumor resection (28). Finally, increased intra-tumoral IL-17 producing cells have been found to correlate with poor survival in HCC patients (10). However none of these studies has been able to demonstrate a mechanistic link as to how Th17 cells potentially contribute to a worse outcome. Therefore, we decided to analyze Th17 cells in HCC patients in more detail with the aim to elucidate their possible function.

Th17 cells have recently been the focus of numerous studies, but only limited information is available on their role in cancer (5). The majority of studies have been performed in murine tumor models (6, 7, 29, 30). Several studies have investigated Th17 cells in cancer patients, however, the function of these cells remains to be shown (8, 9, 11). Animal studies have revealed contradictory and puzzling data as to the role of Th17 cells in tumor immunity. In some studies a beneficial effect of Th17 cells was shown (8, 31, 32), while others have reported opposite results (6, 33). Recently it has been suggested that depending on the setting, the TGF-β/IL-6/IL-23 and IL-17 axis might or might not trigger tumor progression (34).

Previously, different human CD4+IL-17+ T cell subpopulations have been described (23, 35). CCR4+CCR6+ CD4+ T cells are a more homogenous population secreting mainly IL-17 and expressing the Th17 specific transcription factor RORc-2, whereas CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ T cells express mainly IFN-γ and low amounts of IL-17. This population is also referred in other studies as Th1/Th17 cells (23, 36). We decided to examine both IL-17 producing cell populations in parallel. Only the individual/separate functional analysis of CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells and CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ T cells enabled us to unmask the novel function of Th17 cells.

Based on our in vitro results demonstrating that only CCR4+CCR6+ but not CCR4negCCR6+ Th17 cells suppressed CD8+ T cell responses we analyzed both subpopulations in peripheral blood from patients with HCC. Interestingly we observed an increase in frequency of CCR4+CCR6+, but not CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ Th17 cells in peripheral blood of HCC patients. Albeit it was not possible to test the function of CCR4+CCR6+ Th17 cells in vitro due to their low frequency in peripheral blood, it should be noted that CCR4+CCR6+CD127−CD25low CD4+ T cells from HCC patients, which contain approximately 15% IL-17+ cells, were more potent suppressors of autologous CD8+ T cells than CCR4negCCR6+ CD4+ T cells (data not shown).

Interestingly, a different mechanism of Th17 mediated immune suppression has recently been described in a murine model of encephalomyelitis infection (38). In this study, murine Th17 cells up-regulated anti-apoptotic molecules in infected cells thereby protecting them from lytic activity of cytotoxic T cells. In contrast, the inhibition mediated through human CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells was a direct, cell-to-cell contact mediated event, which neutralized effector CD8+ T cell function. We tested a number of different cytokine blocking antibodies (data not shown), however, only neutralization of TGF-β partially reversed the suppressor function of CCR4+CCR6+Th17 cells on CD8+ T cells. TGF-β, which can be produced by both lymphoid and non-lymphoid cells, is known to have direct and T cell mediated effects on tumor growth. While it can directly affect tumor growth, metastasis and angiogenesis, it has been shown that in patients with melanoma, antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell effector function in vitro is inhibited by the addition of TGF-β (39). Furthermore CD4+ regulatory T cells also suppress tumor-specific CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity via a TGF-β dependent mechanism (40), which makes this cytokine an interesting target for cancer immunotherapy.

Until today, Th17 cells have been mainly implicated to be important in the context of inflammation. Interestingly inflammation associated cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6 and TGF-β and IL-23 impair the generation of Th1 responses and promote the induction of Th17 cells. Cytokines secreted by Th17 cells such as IL-17, IL-21 and IL-22 will then support their proliferation, activation and maintenance, which according to the findings presented here impair CD8+ T cell function in part by TGF-β expression. Our data suggests that Th-17 cells can down-regulate important mechanisms critical for immune surveillance and antitumor immunity thereby facilitating tumor growth. Therefore, Th17 cells could not only be one of the major players in modulation of immune response, but they could serve as potential targets for immune based therapies in inflammation-induced cancers.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:485–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weaver CT, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, Harrington LE. IL-17 family cytokines and the expanding diversity of effector T cell lineages. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:821–852. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ye P, Rodriguez FH, Kanaly S, Stocking KL, Schurr J, Schwarzenberger P, Oliver P, Huang W, Zhang P, Zhang J, Shellito JE, Bagby GJ, Nelson S, Charrier K, Peschon JJ, Kolls JK. Requirement of interleukin 17 receptor signaling for lung CXC chemokine and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor expression, neutrophil recruitment, and host defense. J Exp Med. 2001;194:519–527. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Z, Zheng M, Bindas J, Schwarzenberger P, Kolls JK. Critical role of IL-17 receptor signaling in acute TNBS-induced colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:382–388. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000218764.06959.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin-Orozco N, Dong C. The IL-17/IL-23 axis of inflammation in cancer: friend or foe? Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;10:543–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang L, Yi T, Kortylewski M, Pardoll DM, Zeng D, Yu H. IL-17 can promote tumor growth through an IL-6-Stat3 signaling pathway. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1457–1464. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kryczek I, Wei S, Szeliga W, Vatan L, Zou W. Endogenous IL-17 contributes to reduced tumor growth and metastasis. Blood. 2009;114:357–359. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-177360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kryczek I, Banerjee M, Cheng P, Vatan L, Szeliga W, Wei S, Huang E, Finlayson E, Simeone D, Welling TH, Chang A, Coukos G, Liu R, Zou W. Phenotype, distribution, generation, and functional and clinical relevance of Th17 cells in the human tumor environments. Blood. 2009;114:1141–1149. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-208249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyahara Y, Odunsi K, Chen W, Peng G, Matsuzaki J, Wang RF. Generation and regulation of human CD4+ IL-17-producing T cells in ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15505–15510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710686105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang JP, Yan J, Xu J, Pang XH, Chen MS, Li L, Wu C, Li SP, Zheng L. Increased intratumoral IL-17-producing cells correlate with poor survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. J Hepatol. 2009;50:980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang B, Rong G, Wei H, Zhang M, Bi J, Ma L, Xue X, Wei G, Liu X, Fang G. The prevalence of Th17 cells in patients with gastric cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;374:533–537. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowes MA, Kikuchi T, Fuentes-Duculan J, Cardinale I, Zaba LC, Haider AS, Bowman EP, Krueger JG. Psoriasis vulgaris lesions contain discrete populations of Th1 and Th17 T cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1207–1211. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barczyk A, Pierzchala W, Sozanska E. Interleukin-17 in sputum correlates with airway hyperresponsiveness to methacholine. Respir Med. 2003;97:726–733. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2003.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirkham BW, Lassere MN, Edmonds JP, Juhasz KM, Bird PA, Lee CS, Shnier R, Portek IJ. Synovial membrane cytokine expression is predictive of joint damage progression in rheumatoid arthritis: a two-year prospective study (the DAMAGE study cohort) Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1122–1131. doi: 10.1002/art.21749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duerr RH, Taylor KD, Brant SR, Rioux JD, Silverberg MS, Daly MJ, Steinhart AH, Abraham C, Regueiro M, Griffiths A, Dassopoulos T, Bitton A, Yang H, Targan S, Datta LW, Kistner EO, Schumm LP, Lee AT, Gregersen PK, Barmada MM, Rotter JI, Nicolae DL, Cho JH. A genome-wide association study identifies IL23R as an inflammatory bowel disease gene. Science. 2006;314:1461–1463. doi: 10.1126/science.1135245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1118–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greten TF, Papendorf F, Bleck JS, Kirchhoff T, Wohlberedt T, Kubicka S, Klempnauer J, Galanski M, Manns MP. Survival rate in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective analysis of 389 patients. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1862–1868. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greten TF, Manns MP, Korangy F. Immunotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2006;45:868–878. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korangy F, Hochst B, Manns MP, Greten TF. Immunotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;4:345–353. doi: 10.1586/egh.10.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Obermann S, Petrykowska S, Manns MP, Korangy F, Greten TF. Peptide-beta2-microglobulin-major histocompatibility complex expressing cells are potent antigen-presenting cells that can generate specific T cells. Immunology. 2007;122:90–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02616.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cosmi L, De Palma R, Santarlasci V, Maggi L, Capone M, Frosali F, Rodolico G, Querci V, Abbate G, Angeli R, Berrino L, Fambrini M, Caproni M, Tonelli F, Lazzeri E, Parronchi P, Liotta F, Maggi E, Romagnani S, Annunziato F. Human interleukin 17-producing cells originate from a CD161+CD4+ T cell precursor. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1903–1916. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleinschek MA, Boniface K, Sadekova S, Grein J, Murphy EE, Turner SP, Raskin L, Desai B, Faubion WA, de Waal Malefyt R, Pierce RH, McClanahan T, Kastelein RA. Circulating and gut-resident human Th17 cells express CD161 and promote intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med. 2009;206:525–534. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Acosta-Rodriguez EV, Rivino L, Geginat J, Jarrossay D, Gattorno M, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F, Napolitani G. Surface phenotype and antigenic specificity of human interleukin 17-producing T helper memory cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:639–646. doi: 10.1038/ni1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allan SE, Crome SQ, Crellin NK, Passerini L, Steiner TS, Bacchetta R, Roncarolo MG, Levings MK. Activation-induced FOXP3 in human T effector cells does not suppress proliferation or cytokine production. Int Immunol. 2007;19:345–354. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoechst B, Gamrekelashvili J, Manns MP, Greten TF, Korangy F. Plasticity of human Th17 cells and iTregs is orchestrated by different subsets of myeloid cells. Blood. 2011;117:6532–6541. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-317321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu W, Putnam AL, Xu-Yu Z, Szot GL, Lee MR, Zhu S, Gottlieb PA, Kapranov P, Gingeras TR, de St Groth BF, Clayberger C, Soper DM, Ziegler SF, Bluestone JA. CD127 expression inversely correlates with FoxP3 and suppressive function of human CD4+ T reg cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1701–1711. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Budhu A, Forgues M, Ye QH, Jia HL, He P, Zanetti KA, Kammula US, Chen Y, Qin LX, Tang ZY, Wang XW. Prediction of venous metastases, recurrence, and prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma based on a unique immune response signature of the liver microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuang DM, Zhao Q, Wu Y, Peng C, Wang J, Xu Z, Yin XY, Zheng L. Peritumoral neutrophils link inflammatory response to disease progression by fostering angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kryczek I, Wei S, Zou L, Altuwaijri S, Szeliga W, Kolls J, Chang A, Zou W. Cutting edge: Th17 and regulatory T cell dynamics and the regulation by IL-2 in the tumor microenvironment. J Immunol. 2007;178:6730–6733. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muranski P, Boni A, Antony PA, Cassard L, Irvine KR, Kaiser A, Paulos CM, Palmer DC, Touloukian CE, Ptak K, Gattinoni L, Wrzesinski C, Hinrichs CS, Kerstann KW, Feigenbaum L, Chan CC, Restifo NP. Tumor-specific Th17-polarized cells eradicate large established melanoma. Blood. 2008;112:362–373. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-120998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benchetrit F, Ciree A, Vives V, Warnier G, Gey A, Sautes-Fridman C, Fossiez F, Haicheur N, Fridman WH, Tartour E. Interleukin-17 inhibits tumor cell growth by means of a T-cell-dependent mechanism. Blood. 2002;99:2114–2121. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hinrichs CS, Kaiser A, Paulos CM, Cassard L, Sanchez-Perez L, Heemskerk B, Wrzesinski C, Borman ZA, Muranski P, Restifo NP. Type 17 CD8+ T cells display enhanced anti-tumor immunity. Blood. 2009 doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-203935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Numasaki M, Watanabe M, Suzuki T, Takahashi H, Nakamura A, McAllister F, Hishinuma T, Goto J, Lotze MT, Kolls JK, Sasaki H. IL-17 enhances the net angiogenic activity and in vivo growth of human non-small cell lung cancer in SCID mice through promoting CXCR-2-dependent angiogenesis. J Immunol. 2005;175:6177–6189. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muranski P, Restifo NP. Does IL-17 promote tumor growth? Blood. 2009;114:231–232. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-215541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Annunziato F, Cosmi L, Santarlasci V, Maggi L, Liotta F, Mazzinghi B, Parente E, Fili L, Ferri S, Frosali F, Giudici F, Romagnani P, Parronchi P, Tonelli F, Maggi E, Romagnani S. Phenotypic and functional features of human Th17 cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1849–1861. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Human Th17 cells in infection and autoimmunity. Microbes Infect. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hirahara K, Liu L, Clark RA, Yamanaka K, Fuhlbrigge RC, Kupper TS. The majority of human peripheral blood CD4+CD25highFoxp3+ regulatory T cells bear functional skin-homing receptors. J Immunol. 2006;177:4488–4494. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hou W, Kang HS, Kim BS. Th17 cells enhance viral persistence and inhibit T cell cytotoxicity in a model of chronic virus infection. J Exp Med. 2009;206:313–328. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahmadzadeh M, Rosenberg SA. TGF-beta 1 attenuates the acquisition and expression of effector function by tumor antigen-specific human memory CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:5215–5223. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen ML, Pittet MJ, Gorelik L, Flavell RA, Weissleder R, von Boehmer H, Khazaie K. Regulatory T cells suppress tumor-specific CD8 T cell cytotoxicity through TGF-{beta} signals in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:419–424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408197102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.