Abstract

Aims

The US Food and Drug Administration must consider whether to ban the use of menthol in cigarettes. This study examines how current smokers might respond to such a ban on menthol cigarettes.

Design

Convenience sample of adolescent and adult smokers recruited from an online survey panel.

Setting

United States, 2010.

Participants

471 adolescent and adult current cigarette smokers.

Measurements

Respondents were asked a series of questions about how they might react if menthol cigarettes were banned. In addition, participants completed a simulation purchase task to estimate the demand for menthol and nonmenthol cigarettes across a range of prices.

Findings

Overall, 36% respondents said they always or usually smoked menthol cigarettes. When asked how they might respond to a ban on menthol cigarettes, 35% of current menthol smokers said they would stop smoking, and 25% said they would ‘find a way to buy a menthol brand.’ Those who reported they might quit tended to have greater current intentions to quit (OR=4.46), while those who reported they might seek illicit menthol cigarettes were far less likely to report current intentions to quit (OR = 0.06). Estimates for individual demand elasticity for preferred cigarette type were similar for menthol (α = .0051) and nonmenthol (α = .0049) smokers. Demand elasticity and peak consumption were related to usual cigarette type and cigarettes smoked per day, but did not appear to differ by race, gender, or age.

Conclusions

Preliminary evidence suggests that a significant minority of smokers of menthol cigarettes in the US would try to stop smoking altogether if such cigarettes were banned.

Introduction

Cigarettes with menthol flavoring comprise nearly 25% of the cigarettes sold in the US, with a disproportionate share among African Americans, females, and youth.1 Congress required a formal study of menthol’s public health impacts as part of the 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (FSPTCA). While no consistent differential health risk of menthol cigarettes compared to nonmenthol cigarettes is observed,2–5 there is some evidence that individuals who smoke menthol cigarettes, particularly youth and African Americans, have a more difficult time quitting.6–8 Also, there is evidence that menthol cigarettes are more appealing to beginner smokers, many of whom are adolescents, primarily because the menthol masks the harshness of the smoke.9–11 Driven by these data, in March 2011, FDA’s Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee (TPSAC) concluded “removal of menthol cigarettes from the marketplace would benefit public health in the United States”.4

While TPSAC did not explicitly recommend that FDA ban menthol as a cigarette additive, such a move appears to have broad public support. Large majorities of never (83%) and former (71%) smokers, as well as 28% of all current smokers (including 53% of African American smokers) supported a menthol ban in a 2009 national survey.12 In response to a ban, some menthol smokers might quit smoking entirely, others might switch to a non-mentholated cigarette brand or other types of tobacco or nicotine products unaffected by a ban, and still others might seek out illicitly-produced (‘black market’) menthol cigarettes. The 2010 Current Population Survey Tobacco Use Supplement (TUS-CPS) directly asked smokers how they would respond if menthol cigarettes were no longer sold. In response, 39% of menthol smokers said they would quit, 36% said they would switch to nonmenthol cigarettes, and 7% said that they would switch to other tobacco products.13 However, the survey did not pose a question concerning black market products. Warnings that a black market of mentholated cigarettes would likely emerge if the FDA banned menthol have become more prominent.5,14 An econometric analysis commissioned by Lorillard Tobacco concluded that the majority of current menthol users would opt for the black market rather than quit or switch to nonmenthol cigarettes.15 Likewise, in a study by Tauras and colleagues 16 using data from the 2003 and 2006/7 TUS-CPS, smokers did not find menthol and non-menthol cigarettes to be substitutes for one another in an economic sense, based on estimates of cross-price elasticity between menthol/non-menthol status.

Another approach to explore how smokers might be expected to respond to a menthol cigarette ban is to use a purchase simulation task whereby participants are asked to project how many cigarettes they would consume across a range of prices.17–18 The purchase task method has been validated as a means to generate individual demand curves from which indices of consumption and demand can be derived in both adult and adolescent samples.17–20 Recent literature reviews point to such simulation methods as a possible means to investigate the addictive potential of drugs, including tobacco, since individual demand curve characteristics often map onto relative reinforcing efficacy.21–22 Madden and Kalman 23 have used the purchase task to examine the impact of bupropion use on individual demand for cigarettes in a double-blind context. Therefore, this emergent methodology might have utility for studying the potential impact of a policy on future cigarette consumption. A black market for menthol cigarettes implies smokers are willing to incur greater cost (monetary cost, but also opportunity costs such as time in seeking product, expected risks, and potential penalties) to acquire the illicit mentholated product compared to a licit nonmenthol one. In a simulated purchase task, one would expect menthol smokers to exhibit significantly less elastic demand for menthol cigarettes compared to nonmenthol cigarettes.

This study examines how a sample of current smokers might respond to a ban on menthol cigarettes. Specifically, we sought to determine: 1) what proportion of current menthol smokers would be likely to quit versus seek out black market menthol cigarettes; and 2) how demand elasticity differs for menthol and nonmenthol cigarettes, depending on one’s current use of menthol or nonmenthol cigarettes. Our intention was not to provide population estimates, but to provide useful information to guide future research on this topic.

Methods

Participants for this study participated in a larger web-based survey that examined perceptions of novel smokeless tobacco products and packaging (Bansal-Travers et. al., in preparation). In brief, participants were recruited from a consumer panel through Global Market Insite, Inc. (GMI), which has a panel reach of more than 2.8 million individuals in the U.S., with all panelists prescreened and providing a physical address and a unique working email address to reduce fraud. The panel is 69% female, 26% have a HS education or less, and 36% have an income less than $46K (approximately the median US income). Additional information on the GMI panel is available online (http://www.gmi-mr.com). Participants in the GMI panel were invited to participate in the surveys by e-mail. The survey sample was split between smokers and nonsmokers in the following age ranges: 200 14–17 year olds, 200 18–21 year olds, 200 22–25 year olds and 400 26–65 year old (current smokers only). This study concentrated on adolescents and young adults because virtually all tobacco product experimentation and uptake occurs before age 25, and tobacco industry marketing documents emphasize the critical importance of this age group.24 One thousand individuals completed the web-based survey in July 2010 and received compensation of 3 USD. Of these, 471 self-identified current cigarette smokers (defined as having smoked at least 1 cigarette in the last 30 days) were invited to complete additional items related to menthol cigarettes. The Roswell Park Cancer Institute Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol; parental consent was obtained prior to youth participation.

Responses to menthol ban

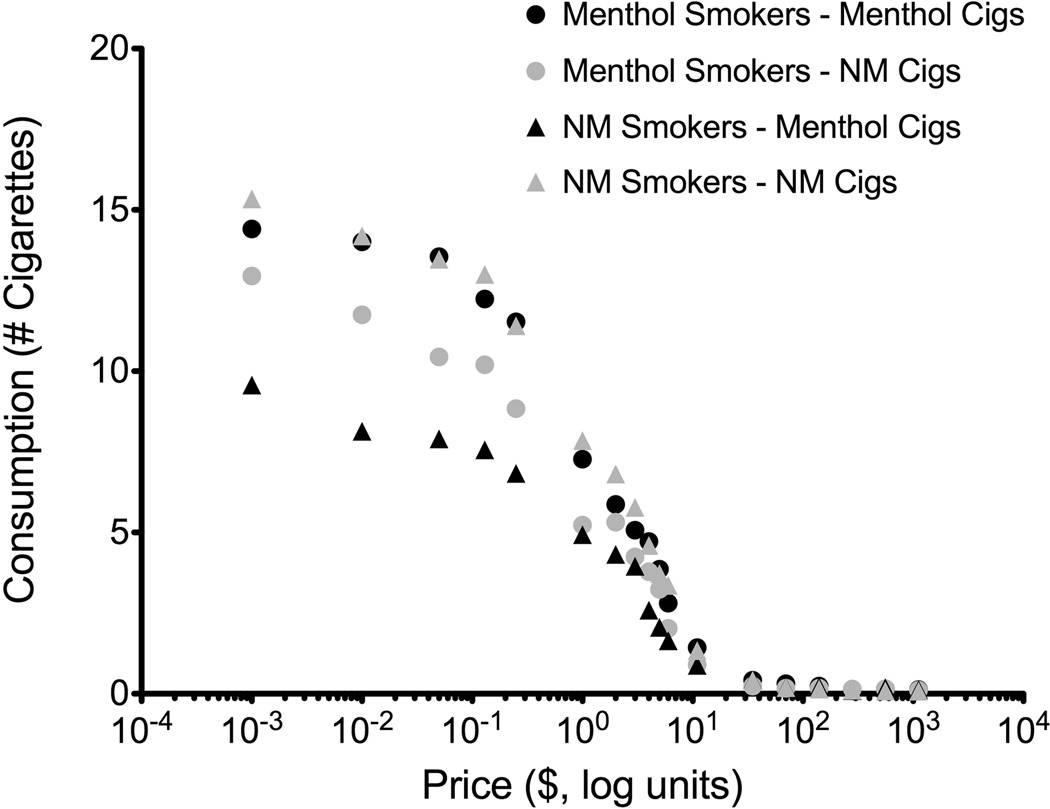

After completing the perception questions, smokers were asked to select one or more of the listed responses (developed by the investigators) that could describe their likely reaction(s) to the following scenario: “The US Food and Drug Administration is considering whether Menthol should be allowed in cigarettes. Please indicate below what best indicates how you would react: If menthol were removed from cigarettes…” Listed response options are provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Percentage of current menthol smokers (N=170) nominating emotional and behavioral reactions to a potential ban on menthol in cigarettes.

Cigarette Purchase Task

Participants completed two iterations of the Cigarette Purchase Task (CPT).18 In the first iteration, participants were asked about the purchase of menthol cigarettes and in the second iteration participants were asked about the purchase of non-menthol cigarettes. The order of iterations (either menthol or non-menthol) was randomized across participants. The purchase task for menthol cigarettes asked participants to imagine a typical day and then report how many MENTHOL cigarettes they would consume if they cost various amounts of money. Participants were told to assume that they had the same income/savings that they had now and NO ACCESS to any cigarettes or nicotine products other than those offered at these prices. In addition, participants were told to assume that they would consume all cigarettes purchased within a day with no stockpiling. Participants were then asked, “How many cigarettes would you smoke if they were [PRICE]?” Participants were asked to respond honestly by entering the number of cigarettes they would smoke if they cost particular dollar amounts ranging from $0 to $1120 per cigarette.18

The exponential demand equation,25 expressed as logQ = logQ0 + k(e−αPs − 1), where α is the rate of change in demand (elasticity), Q0 is peak consumption (at price 0), Ps is price (normalized to Q0), and k is a constant (1.825 in this case, based on best fit to sample average consumption), was applied to CPT data. This equation expresses consumption as an exponentially declining function of price, and has been validated across different appetitive behaviors.24,18,23,20 Hursh and Silberberg 25 propose α as a measure of ‘essential value’; it is also analogous to demand elasticity. In the exponential demand equation, cigarette price is normalized to the cost of obtaining the peak level of consumption, which serves to make elasticity independent of peak consumption. Consistent with other publications, the first zero consumption value was recoded as 0.001 for purposes of logarithmic transformation; subsequent 0 values were ignored.17 Exponential demand equations were fit using Prism 5 curve fitting software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA).

Statistical analyses

Analyses were conducted using SPSS 16.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL). Simple descriptive statistics and crosstabulations with chi-square were used to characterize the sample. Differences in perceptions by menthol status were assessed using ANOVA. Factors associated with quitting and seeking contraband if menthol were to be banned were assessed using logistic regression. Demand curve characteristics by menthol status and hypothetical product type were assessed using generalized estimating equations (gamma distribution, log link function, unstructured correlation matrix, maximum likelihood estimation).

Results

Sample demographics

Of the 471 current smokers, 18.9% only smoked Menthols, 17.2% usually smoked Menthols, 8.1% smoked half Menthol, half non-menthol, 20.6% usually smoked nonmenthol, and 31.4% smoked only nonmenthol. For analysis, we considered the first two categories as ‘Menthol smokers’ (i.e., always or usually smoke menthol; N=170), while the remainder were classified as ‘nonmenthol smokers’ (N=283). Eighteen participants (3.8%) gave no answer to this determining question and were excluded from further analyses. Table 1 shows demographic comparisons of the menthol and nonmenthol smoker groups. As anticipated, Hispanics, and African Americans were significantly more likely to report smoking menthols. Menthol smokers were also more likely to report smoking fewer cigarettes per day. Distributions of menthol smokers on sex and race were similar to the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.26 We also examined indicators of quitting behaviors, such as quit attempts in the past year and plans to quit in the future. Menthol smokers were no different from nonmenthol smokers in reporting no 24-hour quit attempts in the last year (35.1% vs. 35.7%, χ2 (2) = 1.692, p = 0.429). Similarly, menthol and nonmenthol smokers did not differ in plans to quit smoking in the next 30 days (19.9% vs. 24.1%) or in the next 6 months (48.4% vs 42.9%) [χ2 (2) = 1.531, p = 0.465]. These findings are consistent with menthol smokers quit intentions and behaviors in the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Survey.27

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of menthol and nonmenthol smokers

| Menthol | Non Menthol | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 170 | N = 283 | χ2, p | ||

| Age (years) | 14–17 | 10.0 | 7.4 | χ2 (2) = 1.127 |

| 18–25 | 55.3 | 54.8 | P = 0.569 | |

| ≥ 26 | 34.7 | 37.8 | ||

| Sex | Male | 41.2 | 53.4 | χ2 (1) = 6.306 |

| Female | 58.8 | 46.6 | P = 0.012 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | NH White | 63.5 | 76.7 | χ2 (3) = 12.873 |

| NH Black | 9.4 | 3.2 | P = 0.005 | |

| Hispanic | 17.6 | 11.7 | ||

| Others | 9.4 | 8.5 | ||

| Cigs per day | ≤ 5 | 50.0 | 39.9 | χ2 (3) = 5.166 |

| 6–10 | 21.2 | 21.9 | P = 0.160 | |

| 11–20 | 21.8 | 29.0 | ||

| ≥ 21 | 7.1 | 9.2 |

Responses to Menthol Ban

Figure 1 illustrates menthol smokers’ endorsement of various presented options for dealing with the removal of menthol cigarettes from the market. More than 40% of menthol smokers endorsed emotional reactions, reporting they would be angry and/or miss their old brands, and these were the most frequently endorsed reactions. However, only 20% of menthol smokers said they would not consider using a cigarette that did not contain menthol. Over 35% of smokers indicated that a ban on menthol might prompt them to quit smoking. Approximately 25% of menthol smokers indicated they might seek out menthol cigarettes, implying they might consider black market purchases. Some smokers noted that they might seek out menthol in other tobacco products such as cigars (12%) or smokeless tobacco (18%). Ten percent indicated they might try to add menthol to cigarettes themselves.

We performed multivariate analyses (Table 2) on two responses: ‘Try to Quit’ and ‘Find a Way’ (taken as a proxy for seeking black market menthol cigarettes). Those who said they would try to quit smoking were those contemplating a quit attempt, either in the next 30 days or in the next 6 months. Participants 18–25 years old were significantly less likely to say they would try to quit smoking in response to a menthol ban. Conversely, those who said they would seek out black market cigarettes were far less likely to be African-American or intending to quit smoking, particularly in the next 30 days.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of correlates of self-reported contemplation of quitting smoking and seeking out contraband menthol if menthol cigarettes were banned (among menthol smokers).

| "I would try to quit smoking" | "I would find a way to buy a menthol brand" |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | OR | 95% CI | % | OR | 95% CI | |

| SEX | ||||||

| Male | 35.7 | 0.87 | 0.41, 1.83 | 21.4 | 0.47 | 0.19, 1.15 |

| Female | 37.0 | REF | 26.0 | REF | ||

| AGE | ||||||

| 14–17 | 41.2 | 0.35 | 0.09, 1.30 | 23.5 | 3.72 | 0.74, 18.78 |

| 18–25 | 26.6 | 0.25 | 0.10, 0.59 | 25.5 | 2.13 | 0.82, 5.56 |

| 26+ | 50.8 | REF | 22.0 | REF | ||

| RACE | ||||||

| NH White | 35.2 | REF | 31.5 | REF | ||

| NH Black | 43.8 | 1.14 | 0.33, 3.94 | 6.2 | 0.11 | 0.01, 0.98 |

| Hispanic | 40.0 | 1.26 | 0.46, 3.46 | 6.7 | 0.22 | 0.04, 1.07 |

| Other | 31.2 | 0.92 | 0.26, 3.31 | 25.0 | 0.83 | 0.21, 3.32 |

| QUIT INTENTION | ||||||

| 30 days | 53.1 | 4.47 | 1.52, 13.14 | 3.1 | 0.06 | 0.01, 0.52 |

| 6 months | 44.9 | 4.05 | 1.63, 10.08 | 29.5 | 0.81 | 0.34, 1.94 |

| None | 17.6 | REF | 31.4 | REF | ||

| CPD | ||||||

| 0–5 | 36.5 | 4.37 | 0.83, 23.13 | 15.3 | 0.37 | 0.08, 1.63 |

| _6–10 | 50.0 | 4.83 | 0.89, 26.13 | 22.2 | 0.95 | 0.21, 4.42 |

| _11–20 | 27.0 | 1.86 | 0.35, 9.96 | 40.5 | 1.74 | 0.40, 7.48 |

| 21+ | 25.0 | REF | 41.7 | REF | ||

Cigarette Purchase Task

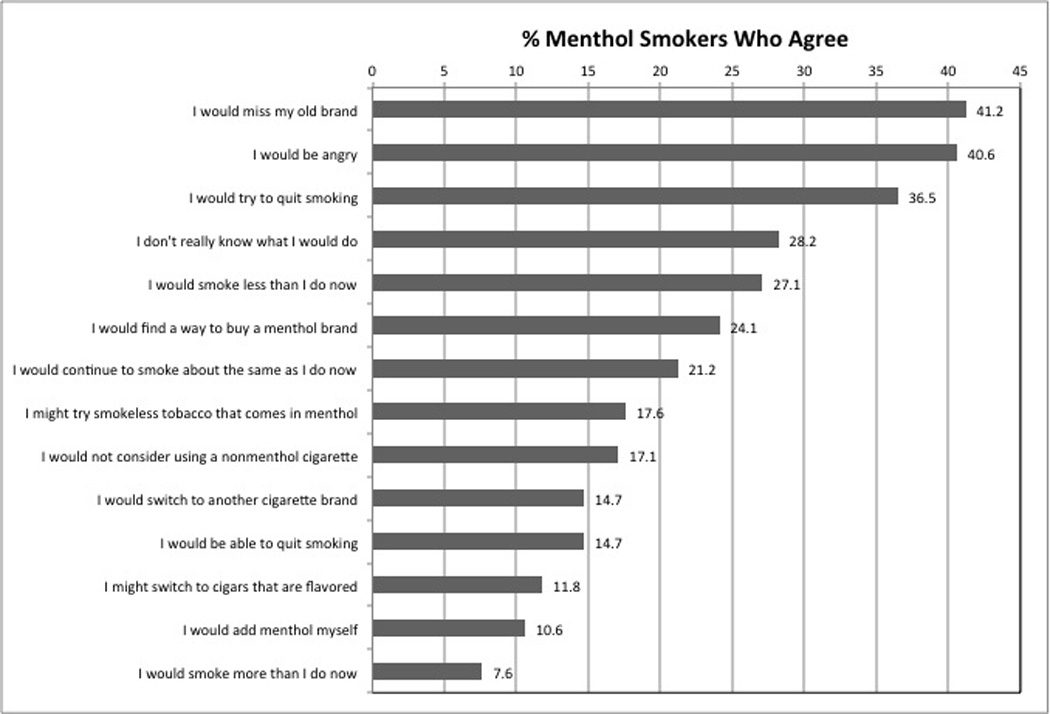

Demand curves fit to group mean menthol and nonmenthol smoker responses to CPT items are illustrated in Figure 2, with curve characteristics shown in Table 3. On average, smokers had lower α values (i.e. less elasticity) for their currently preferred products, which is consistent with the notion that their preferred cigarettes are relatively more reinforcing. The demand elasticity for nonmenthol cigarettes in menthol smokers was approximately 50% greater than the demand elasticity for nonmenthol cigarettes in nonmenthol smokers, whereas the demand elasticity of menthol cigarettes in nonmenthol smokers was approximately 70% greater than the demand elasticity of menthol cigarettes in menthol smokers.

Figure 2.

Sample average consumption of menthol and nonmenthol cigarettes as a function of price (in log $) among menthol and nonmenthol smokers in simulated purchase tasks.

Table 3.

Sample average exponential demand model fit, demand elasticity, and peak consumption for menthol and nonmenthol cigarettes, by current type of cigarette used.

| Menthol Cigs | Nonmenthol Cigs | |

|---|---|---|

| Menthol Smoker Average | ||

| R2 (overall model fit) | 0.979 | 0.992 |

| Q0 (maximum consumption) | 11.7 | 10.2 |

| α (demand elasticity) | 0.0051 | 0.0073 |

| Nonmenthol Smoker Average | ||

| R2 (overall model fit) | 0.965 | 0.979 |

| Q0 (maximum consumption) | 9.3 | 10.1 |

| α (demand elasticity) | 0.0083 | 0.0049 |

NOTES:

Parameters derived from exponential demand equation logQ = logQ0 + k(e −αPs − 1), where α is the rate of change in demand (elasticity), Q0 is peak consumption (at price 0), Ps is price (normalized to Q0), and k is a constant (1.825).

Larger values of α indicate more elastic demand

Among menthol smokers, 21% reported they would consume zero nonmenthol cigarettes for free, while 10% reported they would consume zero menthol cigarettes for free. Among nonmenthol smokers, 10% reported they would smoke zero nonmenthol cigarettes for free, compared to 35% reporting they would consume zero menthol cigarettes for free. We next explored variables associated with individual demand elasticity and peak consumption estimates (see Table 4). For purposes of multivariate analyses, we excluded cases with poor model fit (R2 < 0.30) 20,28 as well as individuals with extreme values on each parameter (determined as >3 standard deviations above the sample mean). Participant age, sex, race, and daily cigarette use (coded as <= 10 vs. >10) served as covariates in the model. We noted a statistically significant interaction between whether a smoker preferred menthol or nonmenthol cigarettes and which type of cigarettes were offered on the CPT in terms of demand elasticity. Specifically, among menthol smokers, demand elasticities were greater for nonmenthol compared to menthol cigarettes, while among nonmenthol smokers, demand elasticities were greater for menthol cigarettes than for nonmenthol cigarettes. We saw similar interactions for peak consumption, such that smokers would consume more of their preferred type relative to the opposite type. Self-reported cigarette consumption was significantly associated with both elasticity and peak consumption. Those who smoked 10 or fewer cigarettes per day showed greater demand elasticity and lower peak consumption. Age, sex, and race were generally not significantly associated with demand curve parameters.

Table 4.

Parameter estimates from GEE models of individual-level elasticity (α) and peak consumption (Q0) estimates by menthol status and CPT for menthol and nonmenthol cigarettes, controlling for participant demographics. Bolded values are statistically significant.

| α | Q0 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | p | B | SE | p | |

| Intercept | −2.47 | 0.47 | <.001 | 2.64 | 0.12 | <.001 |

| Menthol Smoker | 0.55 | 0.30 | 0.066 | −0.06 | 0.08 | 0.493 |

| Nonmenthol Smoker | REF | REF | ||||

| Menthol CPT | 0.41 | 0.21 | 0.046 | −0.13 | 0.04 | 0.002 |

| Nonmenthol CPT | REF | REF | ||||

| Smoker * CPT | −0.81 | 0.25 | 0.001 | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.001 |

| Age 14–17 | −0.60 | 0.52 | 0.24 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.824 |

| Age 18–25 | −0.09 | 0.36 | 0.795 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.147 |

| Age 26+ | REF | REF | ||||

| NH White | 0.06 | 0.40 | 0.891 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.107 |

| NH Black | −0.46 | 0.63 | 0.464 | 0.23 | 0.34 | 0.514 |

| Other | REF | REF | ||||

| Male | −0.40 | 0.34 | 0.240 | −0.01 | 0.08 | 0.892 |

| Female | REF | REF | ||||

| CPD 0–10 | 1.40 | 0.31 | <.001 | −0.75 | 0.08 | <.001 |

| CPD 11+ | REF | REF |

NOTE:

Cases with poor model fit to exponential demand (R2 < 0.30) or with elasticity or peak consumption estimates > 3SD above sample mean were excluded from analysis.

Parameters derived from exponential demand equation logQ = logQ0 + k(e−αPs − 1), where α is the rate of change in demand (elasticity), Q0 is peak consumption (at price 0), Ps is price (normalized to Q0), and k is a constant (1.825).

Larger values of α indicate more elastic demand

Finally, we explored whether those who might seek contraband differed on elasticity and peak consumption. Mann-Whitney U-tests among menthol smokers showed higher peak consumption (median 13.2 vs 7.9; p<.001) and lower demand elasticity (median 0.016 vs 0.060; p=.025) among those who might seek black market menthol cigarettes.

Discussion

The results from this study provided a mixed picture with regard to potential effects of an FDA ban on menthol as a characterizing flavor in cigarettes on smoker behaviors. Self-report measures indicated more than one-third of current menthol smokers would try to quit smoking if menthol were banned, consistent with findings from a large national survey.13 Likelihood of trying to quit in response to a menthol ban was associated with current intention to quit smoking, so a possible outcome of a menthol ban could be to facilitate quitting among those already intending to stop. Furthermore, if the cigarettes they prefer are no longer easily obtained, this may prevent at least some relapse to smoking among those who quit. Levy and colleagues 29 modeled a scenario based on 2003 CPS-TUS data wherein 30% of menthol smokers quit (similar to the current study’s finding on intentions) and showed an overall reduction in smoking prevalence of nearly 10% by 2050, averting over 600,000 deaths.

We found that the demand elasticity of cigarettes (α) was comparable between menthol and nonmenthol smokers for their preferred cigarette type. At the individual level, we did find CPT-task by menthol status interactions with respect to the demand elasticity. We saw that menthol cigarettes were not a perfect substitute for nonmenthol cigarettes in nonmenthol smokers -- menthol cigarettes were associated with greater demand elasticity and lower peak consumption as compared to nonmenthol cigarettes. That is, menthol smokers were somewhat more accepting of nonmenthol cigarettes than were nonmenthol smokers of menthol cigarettes. This suggests that menthol smokers who do not quit may be open to using nonmenthol brands, consistent with respondents’ self-nominated likely responses.

With regard to the potential for the emergence of a black market in menthol cigarettes, one-fourth of current menthol smokers reported they would ‘find a way’ to obtain menthol cigarettes. These individuals had far lower intent to quit and were more likely to smoke 10 or more cigarettes per day, and also showed lower demand elasticity (lower α) for menthol cigarettes, indicating that the sensitivity of these participants to increases in the price of menthol cigarettes was lower. Together these data suggest that the relative reinforcing efficacy of menthol cigarettes in these participants was greater as compared to menthol smokers who reported that they were unlikely to seek out illicit products. One could interpret this to mean there is a ‘hard core’ of menthol smokers who find menthol cigarettes particularly reinforcing and may seek them out even at higher cost, effort, or risk. Evidence from international surveys suggests that smokers who seek out low and untaxed sources of cigarettes have higher dependence, lower intention to quit, and ready access to sources of product.30 A key determinant of the viability of a black market will be access to illicitly produced or imported menthol cigarettes. Laws such as the Prevent All Cigarette Trafficking Act (PACT Act) and agreements among state governments, common couriers, and credit card issuers have reduced the domestic distribution of untaxed cigarettes, and these mechanisms would presumably also depress illicit menthol cigarette distribution.31 Interventions and communications supporting smoking cessation directed toward individuals suspected of making up the “hard core” on menthol smokers, combined with swift and consistent law enforcement efforts, could also help mitigate black market development following a ban on menthol cigarettes.

These findings should be interpreted in light of the limitations of this study. The sample size was relatively small, drew from a commercial internet panel, and was not designed specifically to recruit menthol and nonmenthol smokers. Therefore, these findings might not be broadly generalizable. Overall, 79% of the US population were Internet users in 2010, 68.7% had Internet access at home, with over 81 million fixed internet subscriptions in 2009.32 However, these numbers belie demographic differences; African Americans (66%) and Latinos (62%) are less likely to use the Internet than Whites (77%), and those over 65 (40%) or without a high school diploma (38%) are far less likely to use the Internet.33 We did not formally assess nicotine dependence in this sample, nor did we investigate whether participants had always used their current brand. We also used a single item to assess potential for pursuing contraband product, embedded in a broader list of responses; other approaches to assessing contraband may yield different estimates. However, an important strength of the study is the inclusion of adolescent and young adult smokers, who are of particular interest to regulators charged with examining how different regulatory policies will impact population health. Another strength of this study is our use of the validated purchase task simulation, which allows for an estimation of individual demand elasticity for menthol and nonmenthol cigarettes, and could be applied to study impacts of other policies that affect demand for cigarettes. Future research should apply these approaches to a broader, population representative sample of smokers. These studies should also explore the potential for a black market in more depth, using items that could probe interest in pursuing illicit product more directly, such as how much time and effort one would devote or risk one would accrue to access menthol cigarettes.

In conclusion, we find that among menthol smokers, a greater number of smokers would quit smoking in response to a ban on menthol cigarettes than would seek out alternative sources of menthol. Menthol smokers showed similar demand elasticities for menthol and nonmenthol cigarettes, suggesting that nonmenthol cigarettes would substitute for menthol cigarettes for many current menthol smokers. However, nearly 25% of menthol smokers reported that they would seek out menthol cigarettes, potentially illicitly, and these individuals appeared to be more dependent smokers who had lower demand elasticity for menthol cigarettes. Therefore, should a menthol ban be implemented, increased support for directed anti-contraband communications, cessation interventions, and swift and consistent law enforcement activities to deter contraband should be prioritized.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Kaila Norton and Nicole McDermott for assistance with data analysis.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (P50CA111236). The funder had no role in the design or analysis of the study, nor in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest:

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health. RJO has served as a consultant to the Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee (Tobacco Constituents Subcommittee) of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). RJO (via a subcontract from Research Triangle Institute) reviewed confidential and trade secret documents on menthol cigarettes submitted by tobacco manufacturers pursuant to an FDA request and presented this information in closed session to TPSAC (10 Feb 2011); this information was not used in any way in the current manuscript. KMC has served as a paid consultant to Pfizer Pharmaceutical and received funding from NABI Biopharmaceutical for research investigating a nicotine vaccine for smoking cessation, and has testified as an expert witness for plaintiffs in cases against tobacco manufacturers. LPC is a current employee of Jazz Pharmaceuticals and holds stock options in the company, and in the past has consulted for Dan’s Plan, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, KemPharm, and UCB Pharma. MBT has no tobacco, alcohol, pharmaceutical, or gaming affiliations to report.

References

- 1.Lawrence D, Rose A, Fagan P, Moolchan ET, Gibson JT, Backinger CL. National pattern and correlates of mentholated cigarette use in the United States. Addiction. 2010 Dec;105(Suppl 1):13–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffman AC. The health effects of menthol cigarettes as compared to non-menthol cigarettes. Tob Induc Dis. 2011 May 23;9(Suppl 1):S7. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-9-S1-S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heck JD. A review and assessment of menthol employed as a cigarette flavoring ingredient. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010 Jan;48(Suppl 2):S1–S38. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee. [Accessed 18 April 2011];Menthol Cigarettes and Public Health: Review of the Scientific Evidence and Recommendations. 2011 Mar 18; Available at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/UCM247689.pdf, Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/63dhHPspi.

- 5.Heck JD, Hamm LA, Jr, Lauterbach JH. [Accessed 18 April 2011];The Industry Menthol Report - Menthol Cigarettes: No disproportionate impact on public health. 2011 Mar 23; Available at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/UCM249320.pdf, Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/63dghRH1B.

- 6.Foulds J, Hooper MW, Pletcher MJ, Okuyemi KS. Do smokers of menthol cigarettes find it harder to quit smoking? Nicotine Tob Res. 2010 Dec;12(Suppl 2):S102–S109. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trinidad DR, Pérez-Stable EJ, Messer K, White MM, Pierce JP. Menthol cigarettes and smoking cessation among racial/ethnic groups in the United States. Addiction. 2010 Dec;105(Suppl 1):84–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stahre M, Okuyemi KS, Joseph AM, Fu SS. Racial/ethnic differences in menthol cigarette smoking, population quit ratios and utilization of evidence-based tobacco cessation treatments. Addiction. 2010 Dec;105(Suppl 1):75–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahijevych K, Garrett BE. The role of menthol in cigarettes as a reinforcer of smoking behavior. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010 Dec;12(Suppl 2):S110–S116. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hersey JC, Nonnemaker JM, Homsi G. Menthol cigarettes contribute to the appeal and addiction potential of smoking for youth. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010 Dec;12(Suppl 2):S136–S146. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gardiner P, Clark PI. Menthol cigarettes: moving toward a broader definition of harm. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010 Dec;12(Suppl 2):S85–S93. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winickoff JP, McMillen RC, Vallone DM, Pearson JL, Tanski SE, Dempsey JH, Healton C, Klein JD, Abrams D. US attitudes about banning menthol in cigarettes: Results from a nationally representative survey. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(7):1234–1236. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartman AM. What Menthol Smokers Report They Would Do If Menthol Cigarettes Were No Longer Sold. Presentation to Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee, Food and Drug Administration. 2011 Jan 10–11; Available at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/UCM240176.pdf Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/63dgWDpXw.

- 14.Levinson B. An inquiry into the nature, causes and impacts of contraband cigarettes. Washington DC: Center for Regulatory Effectiveness; 2011. Jan, Available at http://www.thecre.com/ccsf/wpcontent/uploads/2011/06/AnInquiryIntoContrabandCigarettes.pdf Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/63dhCBaek. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Compass Lexecon. Estimating Consequences of a Ban on the Legal Sale of Menthol Cigarettes. Report submitted to Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee, Food and Drug Administraton. 2011 Jan 19; Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/TobaccoProductsScientificAdvisoryCommittee/UCM243622.pdf Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/63dgCKKzX.

- 16.Tauras JA, Levy D, Chaloupka FJ, Villanti A, Niaura RS, Vallone D, Abrams DB. Menthol and non-menthol smoking: the impact of prices and smoke-free air laws. Addiction. 2010 Dec;105(Suppl 1):115–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs EA, Bickel WK. Modeling drug consumption in the clinic using simulation procedures: demand for heroin and cigarettes in opioid-dependent outpatients. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999 Nov;7(4):412–426. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.4.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacKillop J, Murphy JG, Ray LA, Eisenberg DT, Lisman SA, Lum JK, Wilson DS. Further validation of a cigarette purchase task for assessing the relative reinforcing efficacy of nicotine in college smokers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008 Feb;16(1):57–65. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy JG, MacKillop J, Skidmore JR, Pederson AA. Reliability and validity of a demand curve measure of alcohol reinforcement. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009 Dec;17(6):396–404. doi: 10.1037/a0017684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy JG, MacKillop J, Tidey JW, Brazil LA, Colby SM. Validity of a demand curve measure of nicotine reinforcement with adolescent smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011 Jan 15;113(2–3):207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carter LP, Griffiths RR. Principles of laboratory assessment of drug abuse liability and implications for clinical development. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009 Dec 1;105(Suppl 1):S14–S25. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter LP, Stitzer ML, Henningfield JE, O'Connor RJ, Cummings KM, Hatsukami DK. Abuse liability assessment of tobacco products including potential reduced exposure products. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009 Dec;18(12):3241–3262. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Madden GJ, Kalman D. Effects of bupropion on simulated demand for cigarettes and the subjective effects of smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010 Apr;12(4):416–422. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cummings KM, Morley CP, Horan JK, Steger C, Leavell NR. Marketing to America’s youth: evidence from corporate documents. Tob Control. 2002;11(Suppl 1):I5–I7. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hursh SR, Silberberg A. Economic demand and essential value. Psychol Rev. 2008 Jan;115(1):186–198. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Office of Applied Studies United States Department of Health and Human Services. 2009 Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR29621.v1.

- 27.Hyland A, Fix BV, O’Connor RJ, Hammond D, King B, Fong GT, Cummings KM. Use of menthol cigarettes and nicotine dependence: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Survey. POS4-50; Presented at 17th Annual Meeting of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco; 16–19 February 2011; Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reynolds B, Schiffbauer R. Measuring state changes in human delay discounting: an experiential discounting task Behav Processes. 2004 Nov 30;67(3):343–356. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy DT, Pearson JL, Villanti AC, Blackman K, Vallone DM, Naiura RS, Abrams DB. Modeling the future effects of a menthol ban on smoking prevalence and smoking attributable deaths in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(7):1236–1240. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Licht AS, Hyland AJ, O'Connor RJ, Chaloupka FJ, Borland R, Fong GT, Nargis N, Cummings KM. Socio-economic variation in price minimizing behaviors: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011 Jan;8(1):234–252. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8010234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ribisl KM, Williams RS, Gizlice Z, Herring AH. Effectiveness of state and federal government agreements with major credit card and shipping companies to block illegal Internet cigarette sales. PLoS One. 2011 Feb 14;6(2):e16754. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.International Telecommunication Union. Key 2000–2010 country data. Internet Users http://www.itu.int/ITU-D/ict/statistics/material/excel/2010/InternetUsersPercentage00-10.xls Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/63dguA0Ro.

- 33.Fox S. Health Topics: 80% of internet users look for health information online. Pew Research Center, Pew Internet and American Life Project & California HealthCare Foundation. 2011 Feb 1; http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/2011/PIP_HealthTopics.pdf Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/63dgMsrls.