Abstract

Ixodes scapularis ticks transmit many pathogens, including Borrelia burgdorferi, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, and Babesia microti. Vaccines directed against arthropod proteins injected into the host during tick engorgement could prevent numerous infectious diseases. Salp14, a salivary anticoagulant, poses a key target for such intervention. Salp14 is the prototypic member of a family of potential I. scapularis anticoagulants, expressed and secreted in tick saliva during tick feeding. RNA interference was used to assess the role of Salp14 in tick feeding. Salp14 and its paralogs were silenced, as demonstrated by the reduction of mRNA and protein specific for these antigens. Tick salivary glands lacking Salp14 had reduced anticoagulant activity, as revealed by a 60–80% reduction of anti-factor Xa activity. Silencing the expression of salp14 and its paralogs also reduced the ability of I. scapularis to feed, as demonstrated by a 50–70% decline in the engorgement weights. Because ticks have several anticoagulants, it is likely that the expression of multiple anticoagulants in I. scapularis saliva would have to be ablated simultaneously to abolish tick feeding. These studies demonstrate that RNA interference can silence I. scapularis genes and disrupt their physiologic function in vivo, and they identify vaccine candidates that can alter vector engorgement.

Ixodes ticks are obligate ectoparasites distributed worldwide, and they are vectors of human pathogens (1). Ixodes scapularis can harbor multiple pathogens, including Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease agent (2); Anaplasma phagocytophila, the causative agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (3); Babesia microti; and tick-borne encephalitis virus (4, 5). Coinfection and cotransmission of more than one pathogen have been reported (6).

Unlike most hematophagous arthropods that engorge rapidly, ixodid ticks usually take 4–10 days to feed to repletion (7). Ticks are pool feeders that tear their way into the dermis by cementing their hypostome into the skin of a mammalian host, and they suck the blood and fluids that are drained into the resulting wound (8). Components of tick saliva establish and regulate engorgement and facilitate pathogen transmission (9, 10). These molecules promote tick attachment and microbial infectivity by modulating host immune responses and hemostasis, among other functions (9). The generation of immunity against these antigens may alter tick engorgement. Components of I. scapularis saliva, therefore, have potential as vaccines.

Tick salivary proteins with antihemostatic activities maintain the blood meal in a fluid state. Ixolaris, an inhibitor of the factor X–tissue factor VIIIa complex (11), and Salp14, an inhibitor of factor Xa (12), represent two of the prototypic anticoagulants that have been identified in I. scapularis saliva. Proteins that modulate various host immune responses have been characterized also from ixodid tick saliva (13–16). Establishing the physiological relevance of these proteins has relied on conventional protein immunization techniques. Typically, this effort requires the generation of recombinant proteins that can effectively induce neutralizing antibodies against the native salivary protein. Often, recombinant proteins do not mimic the antigenic epitopes of native proteins entirely. Compounding the problem is the observation that the transcriptome of I. scapularis is composed of structural and functional paralogs of many genes (17). Therefore, despite aggressive research, bridging the gap between genomics and functional proteomics remains a tedious task and has hampered the development of vaccines targeting the tick vector.

Posttranscriptional gene silencing by RNA interference (RNAi) provides a powerful alternative to traditional genetics and, thus, has revolutionized the analysis of gene function in nonmodel organisms (18–20). RNAi is mediated by long double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) or small interfering RNAs (siRNAs). Introduction of dsRNA or siRNA into a cell triggers the destruction of the cognate mRNA (21). In a recent report, Aljamali et al. (22) have shown the feasibility of RNAi to abrogate the expression of a histamine-binding protein in the tick Amblyomma americanum. We report here the usefulness of RNAi for examining the physiological role of Salp14, an anticoagulant identified in I. scapularis (12). Salp9pac, a structural paralog of Salp14, was identified also in the salivary gland extracts of I. scapularis nymphs and adults (12). Recombinant Salp14 (rSalp14) showed anticoagulant activity, whereas rSap9pac did not show any anticoagulant activity (12). It is now evident that at least 30 additional paralogs of Salp14 are present in I. scapularis nymphs (E.F., unpublished data) and adults (17). The Salp14 paralogs may exemplify a parsimonious strategy adopted by the tick to target different components of the coagulation cascade or serve other functions. We show that dsRNA-mediated interference disrupts the expression of the majority of the structural paralogs of the Salp14 family, and we begin to address the physiological significance of the Salp14 family.

Materials and Methods

Ticks and Tick-Immune Sera. I. scapularis nymphs were obtained from a tick colony at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station (New Haven, CT). Nymphs were fed to repletion on pathogen-free C3H/HeN mice and allowed to molt to adults. All feeding experiments involved placing 15 adult female I. scapularis on each ear of either naïve or tick-immune New Zealand White rabbits. Ears were secured with cotton socks, and a restraining collar was placed around the neck of each rabbit. Adult I. scapularis males were placed with females at a 1:1 ratio to ensure mating and feeding. To obtain tick-immune rabbits, three New Zealand White rabbits (Charles River Breeding Laboratories) were sensitized to ticks by three infestations with 30–40 adult ticks per animal, with a resting period of 21 days between challenges. To obtain tick-immune rabbit sera, the animals were killed 4 weeks after the final challenge and blood was collected by cardiac puncture (23).

Generation of dsRNA. Fed-adult salivary gland cDNA was prepared as described for fed nymphs (12) and used as template to amplify DNA encoding the full-length salp14 (450 bp; GenBank accession no. AF 209921), full-length salp9pac (410 bp; GenBank accession no. AF 515779) and a partial fragment encoding I. scapularis actin (520 bp; GenBank accession no. AF 426178). Gene-specific primers containing BglII and KpnI restriction sites were used in the PCRs. The primer sequences are as follows: salp14, 5′-GAAGATCTTCATGGGGTTGACCGAACC-3′ and 5′-CGGTACCGCATAAGTTTTTCTCCTG-3′; salp9pac, 5′-GAAGATCTTCATGGGGTTGACTGAG-3′ and 5′-CGGTACCGTATCTTTATTAAG-3′; and actin, 5′-GAAGATCTTGAGAAGATGACCCAG-3′ and 5′-CGGTACCGTTGCCGATGGTGATCACC-3′. The resultant amplicons were purified and cloned into the BglII–KpnI sites of the L4440 double T7 Script II vector (21). dsRNA complementary to the DNA insert was synthesized by in vitro transcription using the Megascript RNAi kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). The dsRNA was purified and quantified spectroscopically. We injected ≈0.5 μl of dsRNA (1 × 1010 molecules per μl) (corresponding to salp14 and salp9pac dsRNA, individually or in combination) or actin dsRNA into the ventral torso of the idiosoma, away from the anal opening of adult I. scapularis females. The injections were carried out by using 10-μl microdispensers (Drummond Scientific, Broomall, PA) drawn to fine-point needles by using a micropipette puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA). The needles were loaded onto a micromanipulator (Narishige, Tokyo) connected to a Nanojet microinjector (Drummond Scientific). Control ticks were injected with 0.5 1 μl of injection buffer (10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5/1 mM EDTA). At least 15 ticks were used in each group. The ticks were allowed to rest for 1 day before placement with uninjected male ticks on the ears of New Zealand White rabbits. Female ticks that fell off on repletion or those that remained attached after 6 days were collected and weighed on a digital balance.

Northern Blot Analysis to Confirm Gene Silencing. Salivary glands were isolated from groups of mock-injected and dsRNA-injected ticks, and total RNA was isolated as described (12). The RNA was spectroscopically quantified, and ≈1 μg was electrophoresed and transferred to Hybond-N membranes (Amersham Biosciences) according to standard protocols (24). DNA fragments corresponding to full-length salp14 and salp9pac were labeled with fluorescein-dUTP by using the Gene Images Random-Prime DNA-labeling module, and hybridization was carried out according to the manufacturer's protocols (Amersham Biosciences). The blots were probed with labeled salp14 and salp9pac individually or in combination. Hybridization was detected by using the Gene Images CDP Star detection module (Amersham Biosciences). Also, the blots were hybridized separately with a fluorescein-labeled dUTP DNA fragment corresponding to full-length salp25D (GenBank accession no. AF 209911).

Western Blot Analysis to Confirm Gene Silencing. Salivary glands were isolated from groups of six to eight experimental and six to eight mock-injected ticks. The tissues were suspended in sterile PBS (10 μl of PBS per salivary gland tissue) and homogenized. Total protein was quantified by using the Bradford method. Equal amounts of salivary gland protein (1 μg) from mock-injected and dsRNA-injected ticks were electrophoresed on an SDS/12% polyacrylamide gel and processed for immunoblotting. The immunoblots were incubated separately with polyclonal antibodies generated against the rSalp14 containing an N-terminal maltose-binding protein (MBP) fusion tag (12) and polyclonal anti-actin antibody (Sigma–Aldrich). Bound antibodies were detected by using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-guinea pig or goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Sigma–Aldrich). The immunoblots were developed by using a Western Lightening chemiluminescence kit (Perkin–Elmer). As a positive control, the blots were also probed with polyclonal guinea pig antibody to another recombinant salivary protein, MBP-conjugated Salp25D (23).

Confocal Microscopy. Salivary glands of mock-injected and experimental ticks (10–12 ticks per group, n = 4 experiments) were dissected in PBS, placed on sialylated slides (PGC Scientific, Gaithersburg, MD), washed in PBS, and fixed in acetone (10 min at 4°C) as described (25). Salivary gland samples were blocked in PBS/10% FCS/0.5% Tween 20 before antibody incubations. Because rMBP-conjugated Salp14 antisera resulted in a high background in confocal microscopy, we used a Drosophila expression system (Invitrogen) to generate a recombinant protein referred to as rDES-Salp14, which was purified according to the manufacturer's instructions. Polyclonal antibodies directed against purified rDES-Salp14 were generated in guinea pigs by using standard regimens, as described for rMBP-conjugated Salp14 (12). Anti-rDES-Salp14 antibodies reacted with native Salp14, as observed by immunoblot analysis of I. scapularis salivary gland extracts (Fig. 3). Primary antibodies to rMBP-conjugated Salp25D (23) and rDES-Salp14 generated in guinea pig were incubated with the fixed salivary glands for 1 h at room temperature at a 1:100 dilution in blocking buffer. Normal guinea pig serum served as a control. Antibody binding was detected by using tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC)-conjugated anti-guinea pig antibody (Sigma–Aldrich) at 1:200 dilution in PBS/10% FCS. Salivary glands were counterstained with 10 μM To-PRO-3 iodide, a nuclear stain (Molecular Probes), for 3 min at room temperature, washed briefly with PBS/0.5% Tween 20, mounted in glycerol, and imaged by using a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope with multitracking to eliminate bleed-through between fluorescent channels.

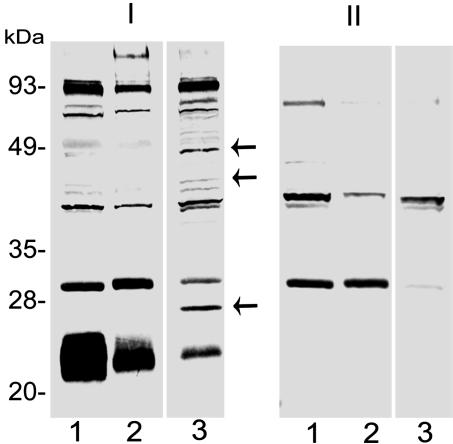

Fig. 3.

Western blot analysis of dsRNA-injected ticks. (A) Untreated adult tick salivary gland extracts (1 μg) separated on an SDS/12% polyacrylamide gel and stained with Coomassie blue (lane 1) or analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-rSalp9pac (lane 2) and anti-rDES-Salp14 (lane 3) antibodies. Lowmolecular-mass protein standards (Bio-Rad) served as markers (lane M). (B) Immunoblotting of protein isolated from the salivary glands of mock-injected (lane 1), actin dsRNA-injected (lane 2), salp14 dsRNA-injected (lane 3), and salp9pac dsRNA-injected (lane 4) ticks probed with anti-rMBP-Salp14 (I) and anti-MBP (II) antibody. (C) Immunoblotting of protein isolated from the salivary glands of mock-injected (lane 1) and salp14/salp9pac dsRNA-injected (lane 2) ticks probed with anti-rMBP-Salp14 (I) and anti-rMBP-Salp25D (II) antibody. (D) Immunoblotting of protein isolated from the salivary glands of mock-injected (lane 1), actin dsRNA-injected (lane 2), salp14 dsRNA-injected (lane 3), and salp9pac dsRNA-injected (lane 4) ticks probed with polyclonal anti-actin antibody.

Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (aPTT) Assay. Salivary gland extracts (2.5 μg) of mock-injected and salp14/9pac dsRNA-injected ticks were assayed for anticoagulant activity in the aPTT assay (26). The salivary gland extracts suspended in a maximum volume of 20 μl were added to 20 μl Alexin HS reagent (Sigma–Aldrich), followed by the addition of 50 μl of normal human plasma, in a 96-well microtiter plate. After incubation for 15 min at 37°C, 20 μl of 50 nM CaCl2 was added to each well and the time to thrombus formation was measured over 3 min at 630 nm by using an MRX hard drive kinetic microplate reader (Dynex Technologies, Chantilly, VA). The clotting time was defined as the time (s) after the addition of CaCl2 at which the rate of increase in OD630 (OD630 per min) reached its maximum value. This value was determined by using the revelation 2.3 computer software program, which was included with the microplate reader. Statistical significance was calculated by using Student's t test.

Factor Xa Inhibition Assay. A single-stage chromogenic factor Xa activity assay (26) was used to measure the inhibitory activity in the salivary gland extracts. Clotting factor Xa (Enzyme Research Laboratories, South Bend, IN) was diluted to 500 pM in 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.5) containing 0.1% BSA and 150 mM NaCl. Duplicate samples of salivary gland extracts from double-stranded salp14/salp9pac RNA-injected or mock-injected ticks (0.5–10 μg of protein) were incubated with 100 μl of factor Xa for 15 min at room temperature in a 96-well microtiter plate. Fifty microliters of 1 mM S-2765 (DiaPharma, West Chester, OH) was added. Substrate hydrolysis was measured at 405 nm over a period of 5 min by using a kinetic microplate reader. Results were expressed as a ratio of substrate hydrolysis in the presence (Vi) or absence (V0) of adult tick salivary gland extract and plotted to evaluate the relative inhibition (26).

Results

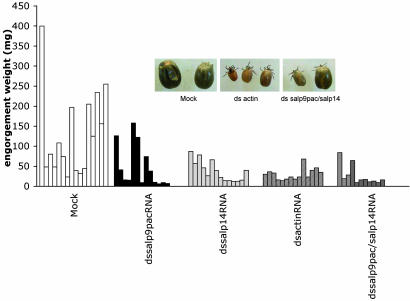

Impact of Gene Silencing on Tick Feeding. Ticks were injected with actin dsRNA or salp14 and salp9pac dsRNA, individually or in combination, as described in Materials and Methods. Ticks were collected after 6 days and evaluated. Aljamali et al. (22) suggested that with prolonged feeding, injected dsRNA might be spit out or diluted by increasing salivary gland mass as feeding progresses, reducing the effect of the treatment. We, therefore, fed the ticks for 6 days. Day 6 was chosen because it is the time when a majority of mock-injected ticks detach or feed to repletion. Adult I. scapularis ticks injected with actin dsRNA fed poorly and were unable to engorge (Fig. 1A). The engorgement weights were significantly lower than those of adult ticks injected with buffer alone. Introduction of salp14/salp9pac dsRNA, either singly or in combination, into I. scapularis adults also resulted in impaired tick feeding, although to a lesser extent than that observed on introduction of actin dsRNA (Fig. 1). Whereas a visible phenotypic change was not obvious in ticks injected with salp14/salp9pac dsRNA, ticks injected with actin dsRNA appeared pale and small in comparison with mock-injected ticks (Fig. 1 Inset).

Fig. 1.

Effect of RNAi targeting of Salp14, Salp9pac, and actin on tick feeding. dsRNA complementary to actin, salp14, and salp9pac was injected into the idiosoma of I. scapularis adults, as described in Materials and Methods. The injected ticks (10–15 ticks per experimental group) were allowed to feed, and they were collected after they detached after feeding to repletion. The engorgement weights were recorded and plotted as a series of histograms to assess feeding efficiency. Inset shows that the ticks in the actin dsRNA-injected group appeared pale and were significantly smaller in comparison with other experimental groups.

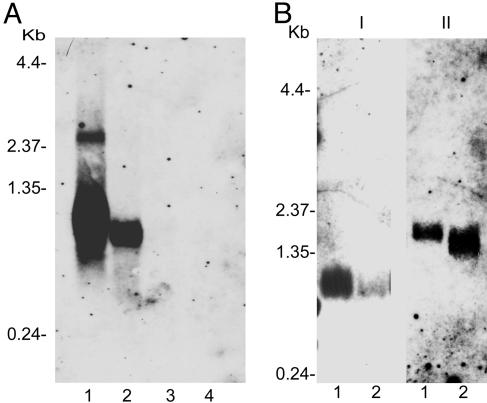

Demonstration of Gene Silencing by Northern Blot Analysis. Total RNA isolated from mock-injected and salp14/9ac dsRNA-injected ticks was analyzed by Northern blotting. The absence or decrease in signal corresponding to salp14 and salp9pac mRNA in the salivary glands of ticks injected with salp14/salp9pac dsRNA, either individually or in combination, indicated the destruction of mRNA corresponding to salp14 and salp9pac (Fig. 2). salp25D mRNA encoding a peroxidase served as a control (Fig. 2B). Equivalent signal for salp25D mRNA in the experimental and mock-injected groups confirmed the sequence-specific targeting of dsRNA-mediated silencing (Fig. 2B). The reason for the shift in the mobility of the mRNA corresponding to salp25D in the experimental group is not clear and could reflect secondary effects on the transcriptome of the tick salivary glands resulting from the disruption of the salp14 family expression. Because there is no obvious sequence homology between salp25D and the salp14 family, we did not expect any direct interaction between the salp14/salp9pac dsRNA and salp25D mRNA.

Fig. 2.

Northern blot analysis of dsRNA-injected ticks. Total RNA was isolated from the salivary glands of mock-injected and experimental ticks, and equal amounts were analyzed by Northern blotting, as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Northern blot analysis of RNA isolated from the salivary glands of mock-injected (lane 1), actin dsRNA-injected (lane 2), salp14 dsRNA-injected (lane 3), and salp9pac dsRNA-injected ticks probed with a fluorescein-labeled salp14 DNA fragment (lane 4). (B) Northern blot analysis of RNA isolated from the salivary glands of mock-injected (lane 1) and salp14/salp9pac dsRNA-injected ticks probed with fluorescein-labeled salp14 DNA fragment (I) and fluorescein-labeled salp25D DNA fragment (II).

Demonstration of Gene Silencing by Western Blot Analysis. Protein extracts of salp14/salp9pac dsRNA-injected and mock-injected tick salivary glands were analyzed by immunoblotting. Antisera raised against rSalp14 crossreacted with rSalp9Pac (12). Salp14 and Salp9pac share 70% identity, and the related structural paralogs share ≈65–89% identity at the protein level (17). We expected that antibodies directed against Salp14 or Salp9pac would crossreact with most members of the family. On immunoblots of adult I. scapularis salivary gland extracts probed with antibodies directed against rSalp9pac or rSalp14, we observed a broad, predominant band between 20 and 28 kDa (Fig. 3A). Electrophoretic separation of tick salivary gland extracts, followed by N-terminal analysis of immunodominant (23) and predominant (17) proteins, demonstrated previously that the Salp14 protein family has a mobility corresponding to ≈26 kDa. salp14 paralogs encode proteins with predicted molecular masses ranging between 9 and 11 kDa (17). Posttranslational modifications presumably contribute to the 20- to 28-kDa molecular mass observed on SDS/PAGE gels. Therefore, immunoblots were probed with anti-rSalp14 antisera to detect and assess the expression of the Salp14 protein family. We observed a significant reduction in the expression of Salp14 and its structural paralogs in salp14/salp9pac dsRNA-injected tick salivary gland extracts (Fig. 3 B and C, I). When a duplicate immunoblot was probed with antisera raised against rSalp25D, equivalent levels of Salp25D protein were detected in the experimental and mock-injected groups (Fig. 3C, II), suggesting that targeted gene silencing had been achieved.

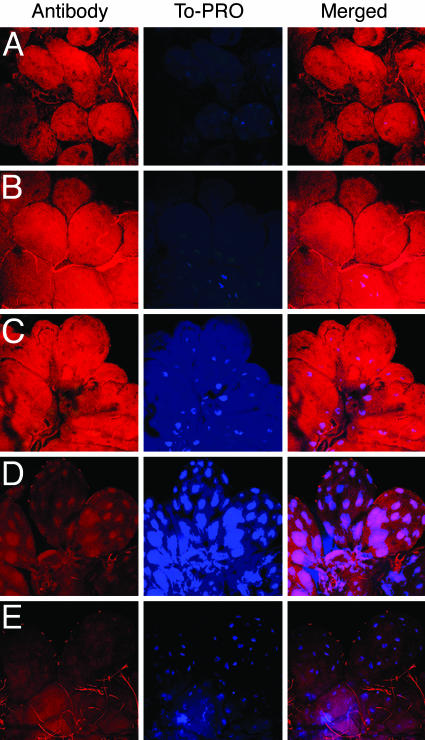

Demonstration of Gene Silencing by Confocal Microscopy. Fixed sections of experimental (salp14/9pac dsRNA) and mock-injected salivary glands were examined for the presence of Salp14 family of proteins by confocal microscopy. The sections represent salivary glands from ticks that had detached or were removed after 6 days of feeding. Both experimental and mock-injected salivary glands reacted equally with guinea pig anti-rSalp25D antibody, as evidenced by the TRITC-conjugated antibody staining of the salivary glands (Fig. 4 A and B). However, the binding of guinea pig anti-rSalp14 antibody to the salivary glands from salp14/9pac dsRNA-injected ticks was reduced, as visualized by the TRITC-conjugated antibody staining (Fig. 4D) in comparison with that observed in mock-injected salivary glands (Fig. 4C). Structural differences indicative of major physiological differences were not apparent within the salivary glands of the mock-injected and dsRNA-injected groups. However, nuclei, visualized by the To-PRO counterstain, were often more prominent in the salivary glands of salp14/9pac dsRNA-injected ticks (Fig. 4D, To-PRO) than in mock-injected salivary glands (Fig. 4 A and C, To-PRO). The reason for the appearance of prominent nuclei in experimental tick salivary glands is unclear.

Fig. 4.

Confocal microscopy of dsRNA and mock-injected tick salivary glands. Salivary glands were isolated from mock-injected and salp14/9pac dsRNA-injected ticks, placed on glass slides, and fixed in acetone. Salivary glands were labeled with normal serum, anti-rSalp14 polyclonal antibody, or anti-rSalp25D polyclonal antibody. Binding was visualized by using TRITC-conjugated secondary antibodies, as described in Materials and Methods. Nuclei were counter-stained with To-PRO-3 iodide. Images were collected by using a ×40 objective. Images are shown both in single (Antibody and To-PRO) and merged fluorescent channels. Salivary glands of mock-injected ticks labeled with antibodies to rSalp25D (A) or rSalp14 (C) showed equivalent labeling, as assessed by the TRITC staining of the salivary acini. Salivary glands of salp14/salp9pac dsRNA-injected ticks showed labeling with anti-rSalp25D antibody (B) that was comparable with that observed in salivary glands of mock-injected ticks (A), as judged by TRITC staining. However, salivary glands of salp14/salp9pac dsRNA-injected ticks failed to label with anti-rSalp14 antibody, as evidenced by a significant decrease in the TRITC staining of the salivary glands (D) when compared with mock-injected ticks (C). naïve guinea pig serum showed little or no binding, as visualized by TRITC staining to salivary glands of mock-injected (E) and dsRNA-injected (data not shown) ticks.

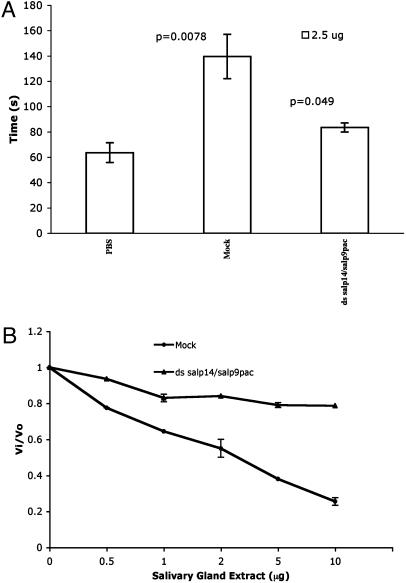

Impact of Gene Silencing on Anticoagulation. The salivary gland extracts of experimental and mock-injected ticks were tested for their ability to prolong the clotting time of normal human plasma in an aPTT assay and to inhibit factor Xa. Inhibition in either assay indicates anticoagulant activity. Salivary gland extracts (2.5 μg) from mock-injected ticks prolonged the clotting time by 77 s. Equivalent amounts of salivary gland extracts from salp14/salp9pac dsRNA-injected ticks prolonged the clotting time only by 20 s. Mock-injected salivary gland extracts (10 μg) inhibited 80% of factor Xa activity, whereas salivary gland extracts lacking Salp14 family inhibited 20–40% of factor Xa activity in different experiments (Fig. 5). Thus, reduced Salp14 family expression decreased the ability of tick salivary gland extracts to inhibit clotting in vitro.

Fig. 5.

Effect of dsRNA-mediated interference of Salp14 family expression on anticoagulation. (A) aPTT assay. The ability of salivary gland extracts from mockinjected and experimental ticks to alter the coagulation time of human plasma was examined in an aPTT assay, as described in Materials and Methods. Whereas salivary gland extracts of mock-injected ticks prolonged the coagulation time of human plasma by 77 s, salivary gland extracts of experimental ticks prolonged the coagulation time of human plasma by 20 s compared with control. Human plasma incubated with PBS served as a control. Statistical significance was calculated by using Student's t test and is indicated above the mock and experimental groups. (B) Chromogenic assay of factor Xa inhibition. Factor Xa-mediated cleavage of chromogenic substrate (500 pM enzyme/1 mM substrate) was measured in the presence of increasing concentrations of salivary gland extracts (0.5–10 μg) from mock-injected and salp14/salp9pac dsRNA-injected ticks. The ratio of velocities of substrate cleavage in the presence (Vi) and absence (V0) of salivary gland extracts is plotted to show the relative inhibition.

Global Impact of Silencing the Salp14 Family. RNAi is a robust technique targeting mRNAs with sequences complementary to the introduced dsRNA (27). However, it is likely that silencing the expression of the Salp14 family may lead to secondary effects on the tick salivary gland transcriptome. Therefore, an immunoblot of experimental and mock-injected adult ticks was probed with tick-immune rabbit sera to test this notion. Whereas antigens corresponding to the Salp14 family were reduced in the experimental group, antigens corresponding to ≈25 and 45 kDa were markedly increased in the experimental group (Fig. 6). We also observed an ≈40-kDa antigen induced in the experimental group, albeit to a lesser extent than the 25- and 45-kDa antigens. Whether these changes reflect the ability of the tick to compensate for the loss of function(s) provided by the Salp14 family will have to be addressed.

Fig. 6.

Disruption of Salp14 family expression and potential secondary effects on the salivary gland proteome. Immunoblotting of protein isolated from the salivary glands of mock-injected (lane 1), actin dsRNA-injected (lane 2), and salp14/salp9pac dsRNA-injected (lane 3) ticks probed with rabbit tick-immune (I) and naïve (II) serum. Arrows indicate proteins that are induced on disruption of Salp14 family expression.

Discussion

The development of tick vector-based vaccines has the potential of targeting multiple infectious diseases transmitted by I. scapularis. Targeting salivary antigens is one approach to thwart tick feeding effectively and block pathogen transmission. Characterizations of tick salivary antigens have, therefore, been based on their ability to (i) induce skin hypersensitivity reaction on tick-resistant animals, (ii) react with anti-tick immune serum, (iii) modulate host immune responses, and (iv) thwart host hemostatic mechanisms (28). Although these approaches have identified several tick salivary proteins (11, 14, 16, 23, 28–31), an effective vaccine against I. scapularis ticks remains elusive. Recently, random sequencing of clones from an adult I. scapularis salivary gland cDNA library identified ≈100 I. scapularis genes (17). Determining the physiological relevance of these gene products, identifying the appropriate vaccine targets, and establishing their vaccine potential remain major obstacles in tick vaccine development. In this article, we demonstrate the usefulness of RNAi to circumvent these problems and enable rapid target discovery and validation.

When dsRNA complementary to the tick actin gene was introduced into the tick hemolymph, the ability of the ticks to engorge was reduced dramatically (Fig. 1). Actin is an important structural protein required for exoskeleton rearrangement during tick engorgement (32). As expected, silencing the expression of actin (Fig. 3D) impaired tick feeding (Fig. 1) by a global attenuation of tick activity unrelated to specific function associated with engorgement. This phenotype of actin dsRNA-injected ticks illustrates the usefulness of RNAi for silencing genes in I. scapularis ticks and assessing their functional significance.

Salp14, a protein identified in the saliva of I. scapularis ticks, was selected for the RNAi study because (i) Salp14 inhibits factor Xa, a protease in the coagulation cascade (12), presumably enabling the tick to thwart host hemostasis during feeding; (ii) Salp14 appears to be a member of a large family of structural paralogs both in I. scapularis nymphs (E.F., unpublished data) and I. scapularis adults (17); and (iii) the Salp14 family includes immunodominant antigens recognized by tick-immune rabbit and guinea pig sera (12). It was reasonable to presume that the Salp14 family may be important for tick feeding and may also be involved in eliciting tick immunity in vertebrate hosts.

RNAi is target-specific, inducing the silencing of genes by destroying only the mRNAs complementary to the introduced dsRNA (21). However, RNAi can also trigger the destruction of mRNAs that contain significant stretches of sequence identity (33), i.e., off-target silencing. salp14 and salp9pac mRNA share 86% identity at the nucleotide level. The transcriptome of I. scapularis adults (17) and nymphs (E.F., unpublished data) appears to encode at least 30 paralogs of Salp14. The physiological significance and temporal expression patterns of these paralogs require further investigation. Because the mRNAs encoding the structural paralogs share 80–94% identity at the nucleotide level (17), off-target silencing of Salp14 and Salp9pac paralogs is expected. Consistent with this notion, introduction of dsRNA corresponding to the full-length salp14 and salp9pac genes, alone or in combination, resulted in a significant decrease in the expression of the paralogous family, as evidenced by Northern and Western blot analyses of salivary gland extracts. Injection of salp14 and salp9pac dsRNA individually appears to trigger the destruction of the salp14 family more effectively (Fig. 2A) than injection with a combination of salp14/salp9pac dsRNA (Fig. 2B). This result is in contrast to the observations made by immunoblot analysis of Salp14 family protein expression (Fig. 3 B and C). We believe that the differences observed between the mRNA and protein expression levels (Figs. 2 and 3) result from experimental variation and biological diversity in the tick population. It is conceivable that RNAi targeting is not uniform in each microinjected tick. The Northern and Western blot analyses were conducted on pools of salivary gland extracts from five or six ticks. Salp14 protein and mRNA levels may correlate better when it is technically possible to perform analyses on individual tick salivary gland extracts. However, the results presented do not detract from the conclusion that RNAi targeting significantly reduces the expression of the Salp14 family at the mRNA and protein levels. Based on the current understanding of the mechanism of RNAi, both single and combination injections should target the salp14 family equally. We therefore do not observe a significant synergistic effect on dual injection. The use of siRNA unique and specific to salp14 or salp9pac will be required to observe the synergistic effect of dual injections

Silencing the expression of the Salp14 family resulted in a 60–80% reduction in the ability of the salivary gland extracts to inhibit factor Xa (Fig. 5). It was evident that the Salp14 family provides a physiological function important for feeding. Depleting this family of antigens reduced tick engorgement. Salp14 paralogs may also aid the tick in digesting the bloodmeal. A bifunctional role for anticoagulants in feeding and in bloodmeal digestion has been described in tsetse flies. Lester and Lloyd (34) showed that tsetse flies with salivary glands removed fed without difficulty but later died with clots found throughout the alimentary canal. A thrombin inhibitor is present in the salivary glands and midguts of tsetse flies (35), implicating an important role for anticoagulants represented in the midguts of blood-feeding arthropods. Transcripts representing Salp9pac have been observed in the midguts of I. scapularis nymphs (12). It is conceivable that interfering with the expression of the Salp14/Salp9pac paralogs in the tick midgut may impact feeding also. Future experiments could possibly assess the ability of dsRNA injected into the hemolymph of I. scapularis to target midgut mRNAs.

Disrupting the expression of the Salp14 family may induce the expression of other anticoagulants or functional paralogs in the tick salivary gland repertoire to compensate for the loss of function provided by the Salp14 family. The observation that feeding was not abolished in the experimental ticks underscores this hypothesis. Random sequencing of cDNA clones from an I. scapularis salivary gland library suggests the presence of functional and structural redundancy in the tick salivary gland transcriptome (17). Western blot analysis of the salivary gland extracts from mock-injected and salp14 dsRNA-injected ticks by using tick-immune rabbit sera indicated a change in the antigenic profile on Salp14 silencing. These changes might represent the up-regulation of other anticoagulants, such as Ixolaris (11), to compensate for the loss of Salp14 family function. The ≈25-kDa antigen that is induced in the salivary gland extracts of salp14/salp9pac dsRNA-injected ticks (Fig. 6) could potentially represent Ixolaris, a 24-kDa anticoagulant identified from an adult I. scapularis salivary gland cDNA library (17). However, antibodies directed against Ixolaris or N-terminal analysis of this protein band would be required to ascertain the identity of the 25-kDa antigen. Simultaneous ablation of Ixolaris and Salp14 family might effectively thwart tick feeding. Gene-expression profiling in conjunction with gene silencing should enable identification of the “fall-back” strategies of the tick. This understanding is crucial to the design of an appropriate coctail vaccine to disable the tick effectively and block pathogen transmission.

B. burgdorferi transmission from infected ticks was not assessed in this study. We anticipate that the 50–70% overall reduction in feeding efficiency may not be sufficient to abolish pathogen transmission. A 50% reduction in engorgement weight should result in a reduction in the pathogen burden in the vertebrate host. However, this estimation is based on the simplistic assumption that feeding rate determines the efficiency of pathogen transmission. This assumption does not take into account the role of vector–pathogen interactions that play a crucial role in pathogen growth in the vector and transmission. We anticipate that abrogation of these interactions may have an impact on transmission without necessarily affecting the rate of tick feeding. It has not been determined whether the Salp14 family is involved in crucial interactions with B. burgdorferi. Future experiments could be conducted on I. scapularis nymphs to assess the impact of Salp14 ablation on pathogen transmission.

The results described here extend the usefulness of the RNAi strategy to determine the in vivo physiological significance of I. scapularis salivary genes and allow rapid discovery of tickvaccine targets. The dsRNA-mediated RNAi approach has enabled the targeted disruption of the Salp14 family as a whole. Elucidating the significance of the individual members of the Salp14 family will require the design and use of siRNA molecules (36, 37). This strategy may provide insights into the evolutionary and biological significance of the redundancy in the tick transcriptome (17). In vivo gene silencing of I. scapularis genes by RNAi also opens the door to an exciting approach for examining vector–pathogen interactions that are crucial for pathogen colonization, growth, and transmission.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Raymond Koski for constructive criticisms and meaningful discussions; Hu Youjia and Lorenza Beati for guidance during microinjections; and Michael Vasil, Lisa Harrison, and Hannah Gould for technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. E.F. is the recipient of the Clinical Scientist Award in Translational Research from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

Abbreviations: aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; dsRNA, double-stranded RNA; MBP, maltose-binding protein; rx, recombinant x; RNAi, RNA interference; TRITC, tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate.

References

- 1.Estrada-Pena, A. & Jongejan, F. (1999) Exp. Appl. Acarol. 23, 685–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbour, A. G. & Fish, D. (1993) Science 260, 1610–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Telford, S. R., III, Dawson, J. E., Katavolos, P., Warner, C. K., Kolbert, C. P. & Persing, D. H. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 6209–6214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mather, T. N., Telford, S. R., III, Moore, S. I. & Spielman, A. (1990) Exp. Parasitol. 70, 55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Telford, S. R., III, Armstrong, P. M., Katavolos, P., Foppa, I., Garcia, A. S., Wilson, M. L. & Spielman, A. (1997) Emerg. Infect. Dis. 3, 165–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levin, M. L. & Fish, D. (2000) Infect. Immun. 68, 2183–2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nuttall, P. A. (1998) Parasitology 116, Suppl., S65–S72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sonenshine, D. E. (1991) Biology of Ticks (Oxford Univ. Press, New York).

- 9.Nuttall, P. A. (1999) Zentralbl. Bakteriol. 289, 492–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ribeiro, J. M. & Francischetti, I. M. (2003) Annu. Rev. Entomol. 48, 73–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Francischetti, I. M., Valenzuela, J. G., Andersen, J. F., Mather, T. N. & Ribeiro, J. M. (2002) Blood 99, 3602–3612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narasimhan, S., Koski, R. A., Beaulieu, B., Anderson, J. F., Ramamoorthi, N., Kantor, F., Cappello, M. & Fikrig, E. (2002) Insect Mol. Biol. 11, 641–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anguita, J., Ramamoorthi, N., Hovius, J. W., Das, S., Thomas, V., Persinski, R., Conze, D., Askenase, P. W., Rincon, M., Kantor, F. S. & Fikrig, E. (2002) Immunity 16, 849–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gillespie, R. D., Dolan, M. C., Piesman, J. & Titus, R. G. (2001) J. Immunol. 166, 4319–4326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillespie, R. D., Mbow, M. L. & Titus, R. G. (2000) Parasite Immunol. (Oxf.) 22, 319–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sangamnatdej, S., Paesen, G. C., Slovak, M. & Nuttall, P. A. (2002) Insect Mol. Biol. 11, 79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valenzuela, J. G., Francischetti, I. M., Pham, V. M., Garfield, M. K., Mather, T. N. & Ribeiro, J. M. (2002) J. Exp. Biol. 205, 2843–2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ullu, E., Djikeng, A., Shi, H. & Tschudi, C. (2002) Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London B 357, 65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grishok, A. & Mello, C. C. (2002) Adv. Genet. 46, 339–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grishok, A., Pasquinelli, A. E., Conte, D., Li, N., Parrish, S., Ha, I., Baillie, D. L., Fire, A., Ruvkun, G. & Mello, C. C. (2001) Cell 106, 23–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fire, A., Xu, S., Montgomery, M. K., Kostas, S. A., Driver, S. E. & Mello, C. C. (1998) Nature 391, 806–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aljamali, M. N., Bior, A. D., Sauer, J. R. & Essenberg, R. C. (2003) Insect Mol. Biol. 12, 299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Das, S., Banerjee, G., DePonte, K., Marcantonio, N., Kantor, F. S. & Fikrig, E. (2001) J. Infect. Dis. 184, 1056–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E. F. & Maniatis, T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Plainview, NY), 2nd Ed.

- 25.Pal, U., Montgomery, R. R., Lusitani, D., Voet, P., Weynants, V., Malawista, S. E., Lobet, Y. & Fikrig, E. (2001) J. Immunol. 166, 7398–7403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrison, L. M., Nerlinger, A., Bungiro, R. D., Cordova, J. L., Kuzmic, P. & Cappello, M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 6223–6229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parrish, S., Fleenor, J., Xu, S., Mello, C. & Fire, A. (2000) Mol. Cell 6, 1077–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mulenga, A., Sugimoto, C. & Onuma, M. (2000) Microbes Infect. 2, 1353–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wikel, S. K. (1988) Vet. Parasitol. 29, 235–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valenzuela, J. G., Charlab, R., Mather, T. N. & Ribeiro, J. M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 18717–18723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang, H. & Nuttall, P. A. (1999) Cell. Mol. Life. Sci. 56, 286–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sauer, J. R. & Hair, J. A. (1986) Morphology, Physiology, and Behavioral Biology of Ticks (Halsted Press, New York).

- 33.Jackson, A. L., Bartz, S. R., Schelter, J., Kobayashi, S. V., Burchard, J., Mao, M., Li, B., Cavet, G. & Linsley, P. S. (2003) Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 635–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lester, H. & Lloyd, L. (1926) Bull. Entomol. Res. 19, 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cappello, M., Li, S., Chen, X., Li, C. B., Harrison, L., Narasimhan, S., Beard, C. B. & Aksoy, S. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 14290–14295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sohail, M., Doran, G., Riedemann, J., Macaulay, V. & Southern, E. M. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scherr, M., Morgan, M. A. & Eder, M. (2003) Curr. Med. Chem. 10, 245–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]