Background: The kynurenine pathway catalyzes tryptophan catabolism in mammals.

Results: The rate-limiting indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and two other enzymes of the host kynurenine pathway are required for an efficient development of the apicomplexan parasite E. falciformis in mouse.

Conclusion: A previously unanticipated pro-parasite function of host tryptophan catabolism is revealed.

Significance: An intracellular pathogen subverts the host defense (IFNγ, IDO1) for progression of natural life cycle.

Keywords: Microbiology; Mouse; Parasite Metabolism; Parasitology; Tryptophan; Apicomplexan Parasite; Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase; Kynurenine Pathway; Tryptophan Catabolism; Xanthurenic Acid

Abstract

The obligate intracellular apicomplexan parasites, e.g. Toxoplasma gondii and Plasmodium species, induce an IFNγ-driven induction of host indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), the first and rate-limiting enzyme of tryptophan catabolism in the kynurenine pathway. Induction of IDO1 supposedly depletes cellular levels of tryptophan in host cells, which is proposed to inhibit the in vitro growth of auxotrophic pathogens. In vivo function of IDO during infections, however, is not clear, let alone controversial. We show that Eimeria falciformis, an apicomplexan parasite infecting the mouse caecum, induces IDO1 in the epithelial cells of the organ, and the enzyme expression coincides with the parasite development. The absence or inhibition of IDO1/2 and of two downstream enzymes in infected animals is detrimental to the Eimeria growth. The reduced parasite yield is not due to a lack of an immunosuppressive effect of IDO1 in the parasitized IDO1−/− or inhibitor-treated mice because they did not show an accentuated Th1 and IFNγ response. Noticeably, the parasite development is entirely rescued by xanthurenic acid, a by-product of tryptophan catabolism inducing exflagellation in male gametes of Plasmodium in the mosquito mid-gut. Our data demonstrate a conceptual subversion of the host defense (IFNγ, IDO) by an intracellular pathogen for progression of its natural life cycle. Besides, we show utility of E. falciformis, a monoxenous parasite of a well appreciated host, i.e. mouse, to identify in vivo factors underlying the parasite-host interactions.

Introduction

Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1)2 is the first and the rate-limiting enzyme of tryptophan degradation via the kynurenine pathway in mammals. Other enzymes of the pathway include kynurenine aminotransferase and kynurenine 3-hydroxylase (supplemental Fig. S1A). Over the last three decades, the tryptophan catabolism has gained an increasing attention because the ensuing depletion of the essential amino acid and the accumulation of downstream products can influence multiple and disparate biological processes such as antimicrobial effect, immunosuppression, cellular transformation, and neuromodulation (1–3). IDO1 is expressed ubiquitously in a variety of tissues (4) and is induced by IFNγ in several cells (5, 6).

IDO1 was first reported to play a defensive role against the parasite Toxoplasma gondii, supposedly by depleting intracellular tryptophan in IFNγ-treated host cells (7). Likewise, an induction of IDO1 in IFNγ-treated host cells was detrimental to bacteria, Chlamydia (8), and Streptococci (9). An elevated in vitro expression of the enzyme also inhibited the replication of genital herpes simplex virus 2 (10) and cytomegalovirus (11). Moreover, the growth inhibition of T. gondii and Chlamydia psittaci could be reversed by exogenous tryptophan (12). Together these reports postulated IDO1 contributing to the host defense by depleting the subcellular tryptophan available to susceptible microbes.

In addition, IDO1 is believed to be an important immunoregulatory enzyme. The biochemical inhibition of IDO in pregnant mice causes rejection of the developing fetus, indicating the importance of this enzyme in pregnancy-associated immunotolerance (13). The immunosuppressive role of IDO1 is thought to be mediated by inhibition of the T-cell proliferation as a consequence of tryptophan starvation (5, 6, 14) and/or due to an elevated apoptosis inflicted by kynurenine metabolites (15–17). Besides, blocking of IDO exerted no apparent effect on the mouse immune response in a toxoplasmosis model, whereas an increase in IFNγ and a decrease in IL-10 level were observed in Leishmania-infected animals (18). It is thus debatable whether an induced expression of IDO is required for the host resistance against the pathogens and/or for antiproliferative effects to counteract an escalated immune response.

Eimeria species belong to the apicomplexan phylum, which comprises obligate intracellular parasites such as Toxoplasma and Plasmodium. Individual Eimeria species infect an exclusive tissue and host cell type and complete their life cycle within a single organism, offering a particular advantage for in vivo and site-specific parasite-host interactions. This study uses Eimeria falciformis, a murine parasite, and demonstrates a previously unanticipated subversion of the host IDO1 and tryptophan catabolism by this parasite.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemical and Biological Reagents

The IDO1 knock-out mice (Balb/c strain) were a kind donation by Muriel Moser (Institut de Biologie et de Médecine Moléculaires, Université Libre de Bruxelles). The parental control Balb/c and NMRI mice were purchased from the Charles River Laboratories (Sulzfeld, Germany). Animal procedures were performed according to the German Animal Protection Laws as directed and approved by the overseeing authority Landesamt fuer Gesundheit und Soziales (Berlin, Germany). E. falciformis oocysts were procured from Bayer.

Propagation of E. falciformis

The natural life cycle of E. falciformis was maintained by continuous passages of the parasite oocysts in female NMRI mice. Oocysts in the animal feces were washed in water, sterilized and floated with NaOCl, and quantified using a McMaster counting chamber (19). The purified oocysts were stored in potassium dichromate at 4 °C and for the experiments were used within 3 months of collection. The 8–12-week-old animals were orally infected with 100 μl of PBS containing the indicated amount of oocysts. Infected mice were kept on grids in separate cages, and oocyst yield was evaluated by collecting feces on a daily basis. Individual fecal samples were dissolved in water and diluted in saturated sodium chloride for counting. All of the animals were weighed every day to monitor their weight loss during the course of infection.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

The female NMRI animals infected with 1500 oocysts were sacrificed on day 1 to day 8 during infection, and their caeca were collected. The parasitized caecal tissues were fixed with 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde and 2.0% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in 100 mm cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) for 4 h at room temperature and for an additional 12 h at 4 °C. Tissues were rinsed with 100 mm cacodylate buffer three times for 15 min and postfixed for 4 h with 2% (v/v) osmium tetroxide and 3% (w/v) potassium hexacyanoferrate (II) on ice. The samples were rinsed once with 100 mm cacodylate buffer for 30 min and then washed with 5 mm maleate buffer three times for 15 min. Tissue samples were stained en bloc with 0.5% (w/v) uranyl acetate, washed again with 5 mm maleate buffer (three times for 15 min), dehydrated in an increasing series of ethanol and propylene oxide, and embedded in Spurr resin. Thin sectioning was performed with a Reichert Ultra Cut, and sections (70–90 nm) were counterstained with 4% (w/v) uranyl acetate followed by lead citrate. All of the samples were imaged on a transmission electron microscope equipped with a wide angle CCD camera (Zeiss EM 900; TRS Systems, Moorenweis, Germany).

Immunohistochemical and Western Blot Analyses

The caeca of infected or uninfected female Balb/c mice were removed, carefully washed, and stored in 4% PFA/PBS for immunohistochemical staining. The tissues embedded in paraffin were cut into 2-μm sections. The samples were treated with xylene, rehydrated in descending ethanol concentrations, and then washed with water. Antigen retrieval was achieved by boiling in citric buffer solution (pH 6.0) in a pressure cooker. The slides were rinsed in water and washed with TBS, and the primary antibody (rat anti-mouse clone mIDO-48; Biolegend) was added (1:200, 30 min). After washing, the sections were incubated with the secondary antibody (biotinylated rabbit anti-rat, 1:200, 30 min, Dako). Streptavidin-conjugated alkaline phosphatase solution was applied (30 min) onto the sections, which were visualized by Fast RED (Dako). The slides were rinsed in water and then counterstained with hematoxylin. The images were acquired using a LEICA DMIL microscope and LEICA DFC 480 camera and processed with LEICA Application Suite (v2.8.1).

Immunoblot analysis of tissue homogenates was performed using polyclonal rabbit anti-IDO and rabbit anti-β-tubulin primary antibodies (Genscript) and horseradish peroxidase-labeled anti-rabbit secondary antibody (GE Healthcare). The caeca of uninfected or infected female NMRI mice were removed, washed, and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total proteins were prepared in a lysis buffer containing 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.2), 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mm PMSF, and protease-inhibitor mixture (Sigma-Aldrich). The samples were homogenized and centrifuged (5 min, 4 °C, 12000 rpm), and the protein amount in the supernatant was determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce). 30 μg of total tissue protein was separated on a 12% SDS-PAGE and blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Applichem). Unspecific binding was blocked by overnight incubation in 5% skim milk powder in TBS containing 0.2% Tween 20 (TBS-T). The primary antibody (1:1000) was applied in blocking solution for 2 h at room temperature, followed by three washes in TBS-T and addition of the secondary antibody (1:3000, 45 min at room temperature). The samples were subjected to three washes in TBS-T, and the protein bands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare). The same blots were used to monitor anti-β-tubulin expression (protein loading) using the immunoblot recycling kit (Alpha Diagnostic). Protein expression was quantified by densitometric method using Adobe Photoshop suite.

Isolation of Epithelial Cells and RNA Analysis

Infected or uninfected caeca were isolated, washed in calcium- and magnesium-free Hanks' balanced salt solution, opened longitudinally, and cut into 5 mm pieces. To isolate epithelial cells, the tissues were transferred into tubes and incubated in Hanks' balanced salt solution and DTT (1 mm) for 30 min and 37 °C with gentle shaking. The supernatants were discarded. The samples were suspended in Hanks' balanced salt solution and EDTA (1 mm), and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C with vigorous shaking every 10 min. Subsequent supernatants were passed through a 70-μm cell strainer (BD Bioscience) into fresh tubes and centrifuged (1500 rpm, 5 min). The pellets were resuspended in 1 ml of TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and stored at −80 °C.

Total RNA was isolated using the PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen). 100 ng of RNA was either reverse transcribed into first strand cDNA (SuperScript III first strand synthesis SuperMix for quantitative RT-PCR; Invitrogen) for standard PCR (1.5 mm MgCl2, 0.2 mm dNTP, 1 μm primers, 1.25 units of GoTaq DNA polymerase) or subjected to quantitative real time PCR (SuperScript III Platinum SYBR Green One-Step quantitative RT-PCR kit with ROX) (primers in supplemental Table S1). Primers for the mouse 18 S rRNA (Mm18S-F/R) and IDO1 transcript (MmIDO1-F/R) were designed based on the NCBI accession numbers NR_003278 and NM_008324.1, respectively. The E. falciformis 18 S rRNA (Ef18S-F/R) primers were designed using the entry AF080614.1, and the gametocyte-specific primers (EfGam56-F/R and EfGam82-F/R) were based on the ongoing genome-sequencing project (kindly made available by Simone Spork (Humboldt University, Berlin) and Christoph Dieterich (Max-Delbrück Center, Berlin)).

Antigen Preparation, Cell Proliferation, and IFNγ Assays

Purified oocysts were digested with 0.4% pepsin (pH 3, 37 °C, 1 h; Sigma-Aldrich). The oocyst pellet was mixed with 0.5-mm glass beads (Sartorius) in a 1:1 ratio, and briefly vortexed to release free sporocysts. To excyst the sporozoites, DMEM containing 0.25% trypsin, 0.75% sodium tauroglycocholate, glutamine (20 mm), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and penicillin (100 units/ml) was added, and the sample was incubated at 37 °C up to 2 h. The free sporozoites were column-purified by DE-52 anion exchange chromatography (20) and adjusted to 2 × 106 parasites/ml in DMEM. The parasite antigen was prepared by three freeze-thaw cycles and stored at −80 °C.

To perform cell proliferation and IFNγ assays, spleens and intestinal mesenteric lymph nodes were extracted, and single cell suspension was prepared by passaging the tissue through a 70-μm strainer. Cell number was adjusted to 3.5 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI supplemented with fetal calf serum (10%), l-glutamine (20 mm), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and penicillin (100 units/ml). 3.5 × 105 cells were incubated in the presence of sporozoite antigen (equivalent to 1.17 × 105 parasites/well) at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 48 h. Supernatants were collected for IFNγ detection, and the cells were pulsed with 1 μCi/well of methyl-[3H]thymidine (GE Healthcare) for 20 h at 37 °C. Incorporation of [3H]thymidine was measured by liquid scintillation counting. The IFNγ levels in the supernatants were measured using the mouse ELISA Ready-SET-Go kit (eBioscience).

Pharmacological Inhibition of Kynurenine Pathway

(S)-4-(Ethylsulfonyl) benzoylalanine hydrochloride (Enzo Life Sciences) inhibits kynurenine aminotransferase II (KAT-II) (21), and Ro61-8048 (Tocris Bioscience) is a competitive inhibitor of kynurenine 3-hydroxylase (22). 100 mm stock solutions in PBS were prepared for both inhibitors. The animals infected with E. falciformis were treated once daily with 1 mm of Ro61-8048 or (S)-4-(ethylsulfonyl) benzoylalanine diluted in PBS. Inhibitors were applied via oral tube. To inhibit indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, the mice were given 1-methyl-dl-tryptophan (5 mg/ml of l-1-MT and 2 mg/ml of d-1-MT; Sigma Aldrich) in drinking water supplemented with artificial sweetener, which was changed every 2 days. All of the treatments started 2 days prior to infection and continued until the end of the experiments.

Data and Statistical Analysis

All of the graphs represent the means ± S.E. of at least three independent experiments with five or six individual mice unless specified otherwise. The two-tailed nonparametric Mann-Whitney test was used for determination of the statistical significance. The p values below 0.05 were considered as significant.

RESULTS

E. falciformis Has a Stringently Regulated Life Cycle in Its Natural Host

We first examined a nonlethal natural infection of the inbred and outbred mice via oral inoculation of the purified oocysts of E. falciformis. The NMRI mice were infected with increasing numbers of oocysts (10–500), and the kinetics of oocyst shedding into animal feces was determined. Irrespective of the inoculums, the first batch of oocyst was detectable on day 7 of infection that continued until day 12, indicating a stringently synchronized development of the parasite (Fig. 1A). The total oocyst output increased at higher doses and correlated with increments in infection inoculums (Fig. 1B). The animals receiving 10 oocysts discharged a total of 1.7 × 106, and a 10-fold higher dose yielded a 3-fold increase in the oocysts (5.3 × 106). A further increment of the initial dose to 500 oocysts resulted in yet another nonlinear enhancement in the oocyst yield (7.5 × 106), indicating a saturated infection (Fig. 1B). Compared with the outbred NMRI animals, the inbred Balb/c strain receiving equivalent inoculums yielded a similar kinetics of oocyst shedding (supplemental Fig. S2A). Both strains produced their first batch of oocysts on day 7, and the peak days were not influenced at low and high doses (Fig. 1A and supplemental Fig. S2A), confirming identical prepatent and patent periods regardless of the animal breeding or inoculums.

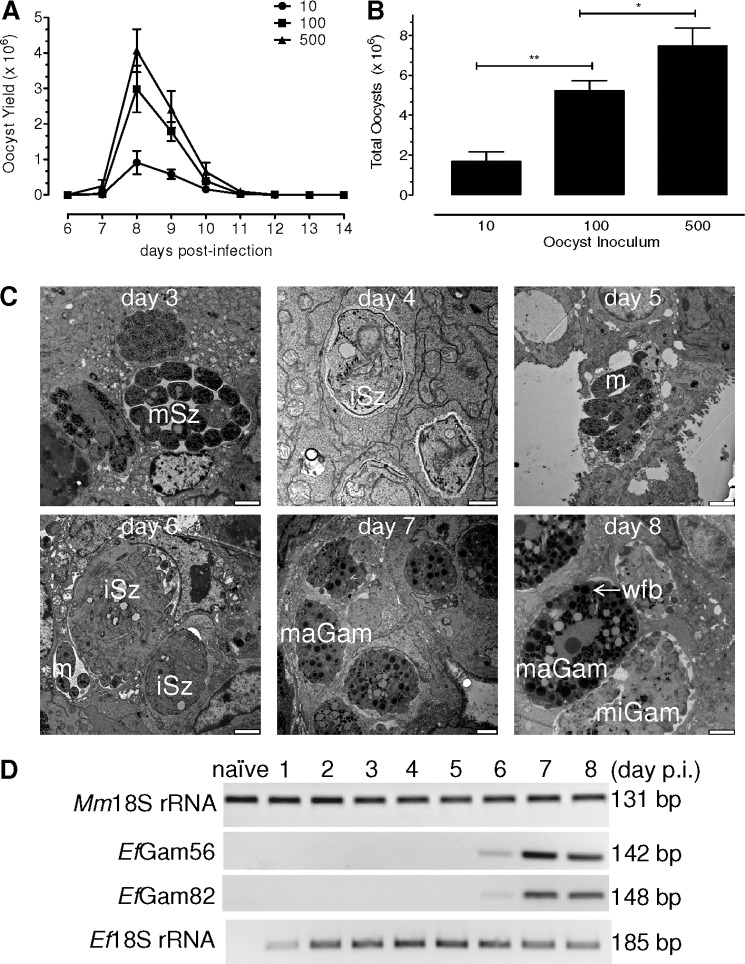

FIGURE 1.

Life cycle of E. falciformis in its natural host, the mouse. A, NMRI mice were infected with indicated amounts of oocysts. The parasite yield was evaluated from day 6 until day 14 postinfection. B, total shed oocyst in response to varying inoculums. C, NMRI mice infected with 1500 oocysts were dissected from day 3 to day 8 of infection, and parasitized caeca tissue samples were subjected to transmission electron microscopy. Only the representative images are shown in the panel. Bars, days 3 and 5–8, 2.5 μm; day 4, 1 μm. D, PCR detection of parasite growth and transition to sexual development. Total RNA was isolated from the parasitized NMRI animals infected with 50 oocysts and subjected to standard PCR for indicated transcripts. The Ef18S and Mm18S rRNA was detectable throughout the course of infection. EfGam56 and EfGam82 were first detectable on day 6 postinfection. The bars represent the means ± S.E. of two independent assays each with three to five animals. iSz, immature schizont; mSz, mature schizont; m, merozoite; maGam, macrogametocyte; miGam, microgametocyte; wfb, wall-forming body.

The parasitized animals were weighed every day to assess the infection-associated pathology, deduced by loss in their body weight (supplemental Fig. S2, B and C). Infection at all doses resulted in a modest reduction of weight from day 7 to day 10 of infection in two strains, which was subsequently followed by a recovery on day 11 and onwards. Neither NMRI (supplemental Fig. S2B) nor Balb/c (supplemental Fig. S2C) infected with 10 oocysts showed a loss of more than 6% of the weight when compared with day 5. Interestingly, a considerably higher dose of 500 oocysts was well tolerated, and animals did not lose more than 10–15% of their body weight. In brief, these results reveal that E. falciformis completes its natural life cycle in a 1-week period, irrespective of the inoculums or strains. These data confirmed the suitability of both mouse strains for further assays using considerably variable inoculums of E. falciformis.

Asexual and Sexual Development of E. falciformis in Mouse Caecum

We next performed transmission electron microscopy to investigate in vivo progression of E. falciformis in NMRI mice (Fig. 1C). The animals were infected with a dose of 1500 oocysts for an easier identification of the parasitized sections in infected caeca. As summarized below, E. falciformis exhibited asexual and sexual stages within the 1 week of its life cycle. Infection on days 3 and 4 revealed immature and mature schizonts in the parasitized epithelial cells of the caecum, which indicated the progression of asexual development (Fig. 1C, day 3 and day 4). The nuclei within the immature schizonts on day 6 represent developing merozoites, which were released following the host cell rupture and detectable in axenic or intracellular form (Fig. 1C, day 5). Imaging of early development was not feasible in infected sections collected on days 1 and 2. The onset of parasite growth, however, was quite evident on these days as deduced by 18 S ribosomal RNA (Fig. 1D). The ratio of host and parasite RNA increased over 7 days and then declined on day 8, indicating a constant increase in parasite burden followed by completion of its life cycle (supplemental Fig. S1B).

An immature macrogamont and a mature macrogamont with a central nucleus and wall forming bodies were observed on days 7 and 8, which marked the initiation and succession of sexual development (Fig. 1C, day 7 and day 8). Fig. 1C (day 8) shows a microgamont with microgametes adjacent to a macrogamont. The transition to sexual phase on day 6 was confirmed by detection of EfGam56 and EfGam82 transcripts identified between days 6 and 8 (Fig. 1D). The homologs of EfGam56 and EfGam82 proteins are expressed in a macrogamont-specific manner in the avian species of Eimeria (23). Taken together, we show the entire natural development of E. falciformis in mouse, which consists of distinct asexual and sexual stages in the epithelial cells of host caecum.

E. falciformis Induces Expression of Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in Mouse Caecum Epithelia

To examine the expression of IDO1 during in vivo development of E. falciformis, the naïve control and parasite-infected mice were sacrificed, and samples were isolated for quantitative PCR (Fig. 2A) and Western blot (Fig. 2B). Compared with uninfected control, the IDO1 transcript was up-regulated by 64-fold on the first day of infection, and amplified by more than 250-fold on day 3. The relative amount of IDO1 mRNA increased further up to 400-fold on day 5 and subsequently decreased to about 230-fold during the late infection (day 7). In accord with quantitative PCR, immunoblot analysis of uninfected and infected caeca revealed a similar outcome (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, IDO1 protein as a 46-kDa band was first detectable on day 2 of infection, which then persisted throughout the parasite life cycle. The observed lag in protein expression suggests a post-transcriptional regulation of IDO1. The enzyme expression reached a maximum on day 5 and then declined until day 7, as quantified by immunoblot performed on samples from three independent in vivo infections (Fig. 2C). In brief, we show that E. falciformis infection of mouse results in the induced expression of host IDO1 in the parasitized caecum.

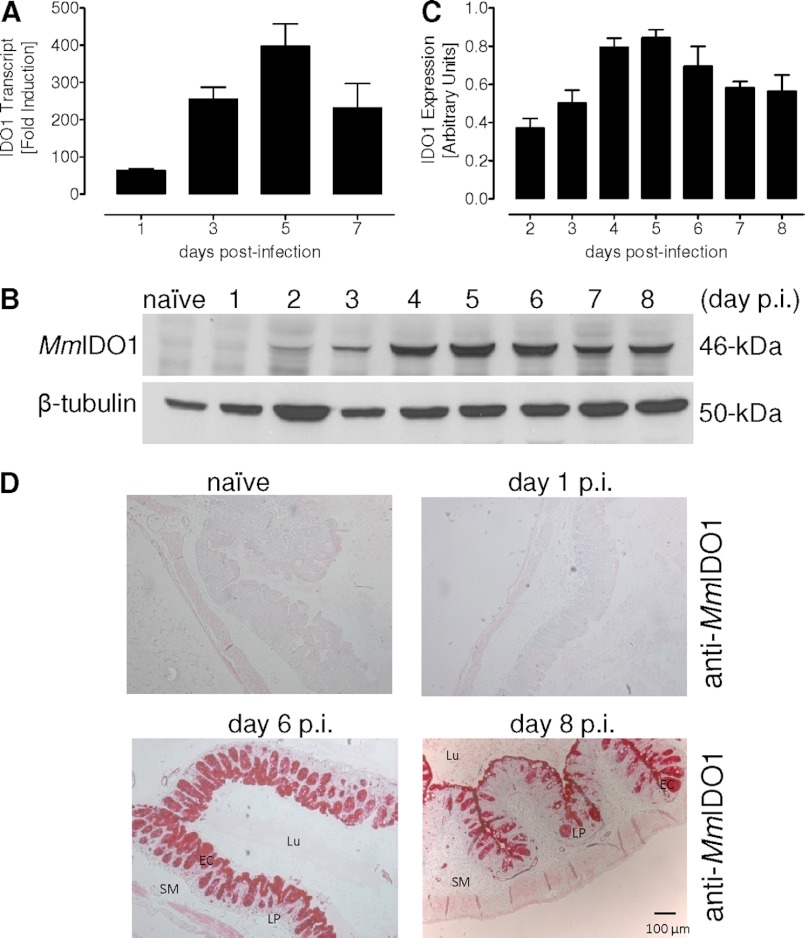

FIGURE 2.

E. falciformis induces indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in the mouse caecum epithelium. A, quantitative PCR of IDO1 transcript in the parasitized and enriched epithelial cells. The fold induction was normalized to the Mm18S rRNA. The bars show the means ± S.E. of three independent experiments. B, immunoblot of the caeca tissue collected on various days of infection. MmIDO1 was detected as a single band of 46-kDa, and β-tubulin (50-kDa) was included as a loading control. C, the tissue homogenates were subjected to anti-MmIDO1 and anti-Mmβtubulin immunoblot analysis (B). Expression of IDO was calculated by densitometric means and normalized to β-tubulin. Three independent blots were used, and the means ± S.E. are shown. D, immunohistochemical staining of IDO in the caecum of naïve and infected (day 1, day 6, and day 8) Balb/c mice. EC, epithelial cell; Lu, lumen; LP, lamina propria; SM, submucosa; p.i., postinfection.

To precisely determine the site of IDO expression within the parasitized host tissue, the caeca of control and infected animals were subjected to immunohistochemical staining. As expected from Fig. 2B, no IDO staining of the naïve tissue was observed. Also, neither epithelial nor cells of the lamina propria appeared stained for IDO protein up to 24 h of infection (Fig. 2D). In contrast, a strong expression of IDO was evident in caecal epithelial cells on days 6 and 8 of infection. An apparent reduction in IDO expression on day 8 (Fig. 2D) corresponds to the protein quantification (Fig. 2C) and is likely a consequence of host cell lysis by the parasite. Collectively, we demonstrate a strong and selective induction of IDO in the epithelial cells of mouse caecum in response to infection with E. falciformis.

Host Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase Is Required for Parasite Development

Induced expression of IDO exerts an antimicrobial effect on susceptible pathogens, likely by depleting the subcellular tryptophan (24). To examine the significance of IDO for in vivo development of E. falciformis, we infected the IDO1−/− (Balb/c) mice and evaluated the entire parasite development as indicated by oocyst formation (Fig. 3). Surprisingly, deficiency of IDO reduced the oocyst yield to nearly half of the control group. Whereas the parental mice produced a total of 6.7 × 106 oocysts, the IDO1−/− group shed only 4 × 106 oocysts corresponding to a significant reduction (p < 0.0001) of 2.7 × 106 oocysts in transgenic animals (Fig. 3A). The kinetics of oocyst shedding remained unaltered in the IDO1−/− group (Fig. 3B), and the decline in yield was confined to the peak days of infection (day 8, p < 0.001; days 9 and 10, p < 0.0001). The growth of E. falciformis was not completely abolished in the absence of IDO1 that might be attributed to the presence of IDO2. This prompted us to inhibit the total IDO activity using a specific and competitive inhibitor (1-MT) (Fig. 3C). Inhibition of enzyme activity by 1-MT treatment of the NMRI mice via the drinking water reduced the oocysts yield to 35% (p < 0.0001) compared with the untreated control. An equivalent phenotype with 55% fewer oocysts (p < 0.001) was obtained when using the Balb/c strain.

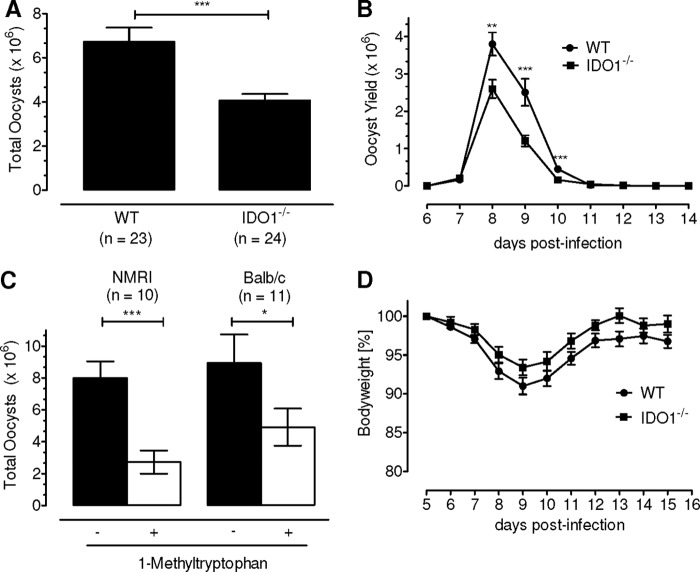

FIGURE 3.

IDO is required for the in vivo development of E. falciformis. A, WT Balb/c and IDO1−/− mice were infected with 50 oocysts, and the parasite development was quantified by counting the number of oocysts shed in feces. B, kinetics of oocyst release from days 6–14 postinfection. The bars show the means ± S.E. of three independent assays each with eight animals/group. C, effect of 1-MT treatment on the in vivo development of E. falciformis. Outbred NMRI or inbred Balb/c animals were infected with 50 oocysts, and the oocyst yield in comparison with untreated controls was determined. The bars represent the means ± S.E. of two independent experiments with five to six animals/group. D, body weight loss in WT Balb/c and IDO1−/− mice from A. *, p ≤ 0.05; **, p ≤ 0.005; ***, p ≤ 0.0005.

The prepatent and patent periods of the parasite growth were not influenced, and the observed effect was due to the decline in oocyst shedding on the peak days of infection in both mouse strains (days 8–10; supplemental Fig. S3, A and B). The body weight loss in the parasite-infected IDO1−/− (Fig. 3D) or drug-treated animals (supplemental Fig. S3, C and D) during the days 7–10 were comparable with respective controls, indicating that the absence of IDO1 or analog inhibition of the total enzyme activity did not affect the morbidity. Taken together, these results suggest that IDO activity is required for an optimal in vivo development of E. falciformis. Notably, this observation contrasts with the reported defensive function of IDO against other pathogens, in vitro.

Parasite-infected IDO1−/− and 1-MT-treated Mice Are Not Impaired in Th1 Immune Response

Induction of IDO activity is also known to have an immunosuppressive effect on T-cell proliferation and on IFNγ production (5, 15, 16, 25). Inhibition or absence of IDO in the parasitized 1-MT-treated or IDO1−/− animals, therefore, has the potential to augment the immune response and reduce the oocysts production. To test this notion, we infected IDO1−/−, 1-MT-treated, and control animals with E. falciformis, and sacrificed them on days 6 and 8, which correspond to a prominent infection and coincide with the induced expression of IDO. The measurement of Th1 cell proliferation and IFNγ responses in the mesenteric lymph nodes of intestine, as well as in the spleen cells, revealed a comparable parasite-specific proliferation in both assay groups compared with the wild type control (supplemental Fig. S4, A and B). In addition, no notable differences in the levels of IFNγ were detectable following E. falciformis infection (supplemental Fig. S4, C and D). Briefly, the parasite-infected IDO1 knock-out and 1-MT-treated animals mount a normal Th1 and IFNγ response against the parasite. Hence, a decline in parasite growth in the IDO-deficient mice is not likely due to an amplified immune response.

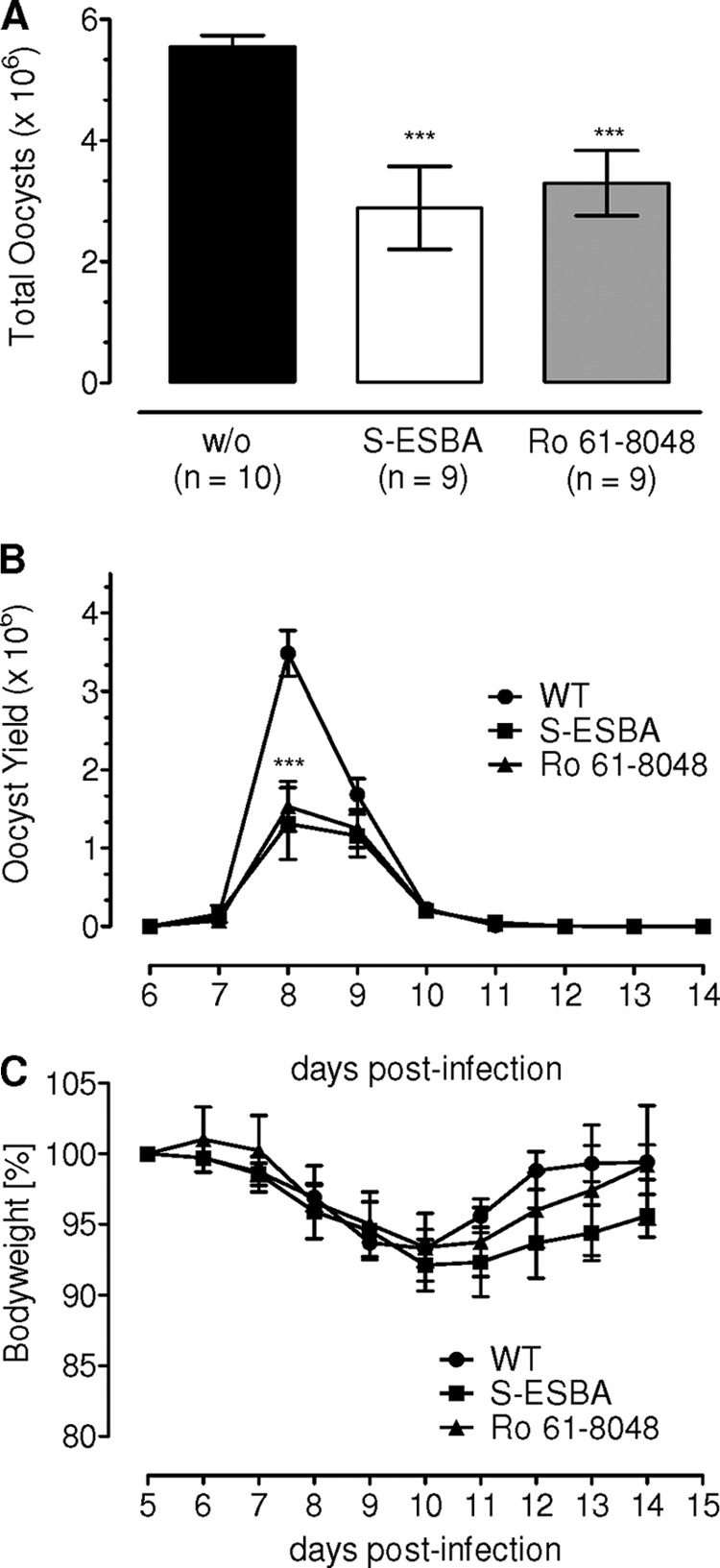

Inhibition of Kynurenine Pathway Enzymes Is Detrimental for Parasite Development

We reasoned whether a downstream metabolite of the tryptophan catabolism via the kynurenine pathway underlies the observed effect on E. falciformis. To test this conjecture, we focused on two enzymes, KAT-II and kynurenine 3-hydroxylase (Kyn-3OH), for which specific inhibitors with proven efficacy in mouse models are available. KAT-II and Kyn-3OH are selectively inhibited by (S)-4-(ethylsulfonyl) benzoylalanine hydrochloride (21) and Ro61-8048 (22), respectively (supplemental Fig. S1A). The mouse can tolerate relatively high doses of (S)-4-(ethylsulfonyl) benzoylalanine hydrochloride (5 mm) (26) and Ro61-8048 (200 mg/kg body weight) (27) via different application routes without apparent signs of mortality and morbidity. We applied them orally at much lower doses ((S)-4-(ethylsulfonyl) benzoylalanine hydrochloride, 1 mm; Ro61-8048, 2 mg/kg) and monitored the oocyst output in comparison with the control carrier-treated animals (Fig. 4A). Notably, as observed for IDO1−/− and for 1-MT-treated mice, the use of S-(S)-4-(ethylsulfonyl) benzoylalanine, as well as of Ro61-8048, reduced the total oocyst yield. Blocking of KAT-II and Kyn-3OH resulted in a decline by 50% (p < 0.0001) and 40% (p < 0.001), respectively, yet again, application of the inhibitors yielded a normal kinetics of oocyst shedding, indicating no apparent influence on the prepatent and patent periods (Fig. 4B). In addition, exposure to the drugs had no effect on morbidity as scored by the loss in body weight of experimental animals compared with respective control groups (Fig. 4C). Consistent with the above findings, we show that perturbation of three distinct enzyme activities along the kynurenine pathway exerts a similar phenotype, strongly suggesting the requirement of a downstream metabolite for an efficient parasite development.

FIGURE 4.

Inhibition of 3-kynurenine hydroxylase and kynurenine aminotransferase impairs the life cycle of E. falciformis. Balb/c mice infected with 50 oocysts were treated with (S)-4-(ethylsulfonyl) benzoylalanine hydrochloride (S-ESBA) or Ro61-8048. Total oocyst yield (A) and output kinetics (B) were quantified in treated and control animals. Body weight of animals (C) was monitored to deduce any signs of morbidity in groups from A. The graphs show the means ± S.E. of two independent experiments each with five mice/group. ***, p ≤ 0.0005.

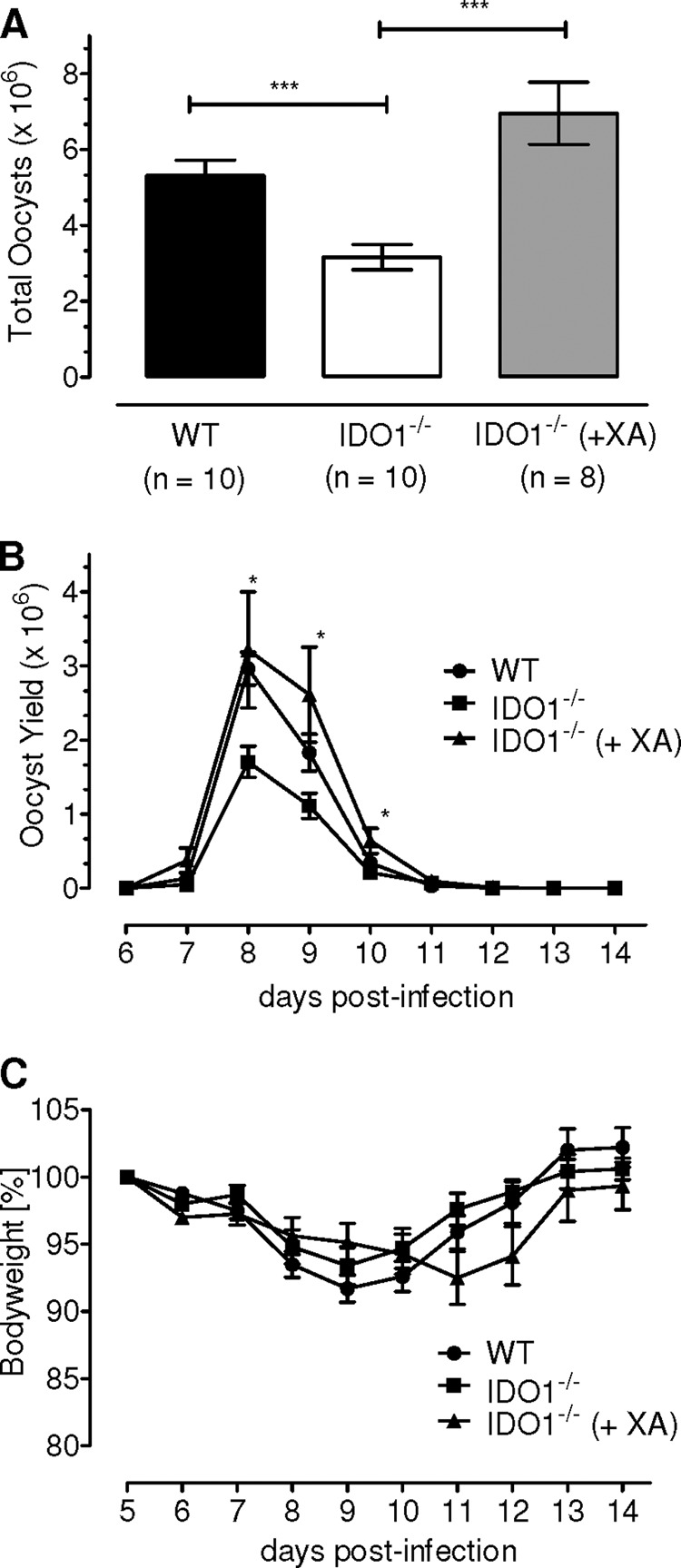

Xanthurenic Acid Can Restore Decline of Oocyst Yield in IDO1−/− Mice

Xanthurenic acid (XA) is an end metabolite of the tryptophan catabolism (supplemental Fig. S1A). The urinary amount of XA is increased 3-fold in response to induction of IDO in mouse (4). Moreover, sequential catalysis by IDO, Kyn-3OH, and KAT-II, whose inhibition is detrimental to E. falciformis growth, merges in synthesis of XA. Therefore, we questioned whether XA is required by the parasite, and its exogenous application can counteract for the IDO deficiency. To assess the notion, the metabolite was administered to the parasite-infected IDO1−/− animals, and the oocysts were enumerated. As expected, the absence of IDO1 reduced the amount of oocyst to nearly half compared with wild type control (Fig. 5A), and the treatment with XA completely rescued the oocyst decline in transgenic animals (p < 0.0001). In fact, the XA-treated animals yielded a 32% higher oocyst count (7 × 106) compared with untreated wild type (5.3 × 106), which, however, did not meet statistical significance. Fig. 5B shows that the course of infection was not affected in response to the metabolite exposure as judged by a natural kinetics of oocyst release. Also, XA did not influence the infection-associated pathology (Fig. 5C), which further signified a specific and positive effect on the parasite development. In brief, these results demonstrate that XA, a by-product of tryptophan degradation, is indeed required for an optimal progression of E. falciformis in mouse.

FIGURE 5.

Xanthurenic acid can completely restore the impaired parasite development in IDO1−/− mice. Total parasite yield (A), as well as the kinetics of oocyst shedding (B), was measured in the indicated groups. Body weight of animals (C) was monitored to deduce any signs of morbidity in groups from A. The bars show the means ± S.E. of two independent experiments with five animals/group. *, p ≤ 0.05; ***, p ≤ 0.0005.

To gain further insight into the action of XA on E. falciformis development, we infected IDO1−/−, XA-treated transgenic, and parental animals and performed quantitative PCR of caecum-derived RNA samples. As shown above (Fig. 1D and supplemental Fig. S1B), Ef18S rRNA was used to score asexual growth from days 3 to 5, and the presence of EfGam82 and EfGam56 (d6–8) indicated the macrogametocyte development (Fig. 6). Specific amplification of individual expressed sequence tags and their expected sizes was confirmed by gel electrophoresis (Fig. 6A). Next, we compared the abundance of each transcript among the three parasitized mice samples (Fig. 6, B–D). No apparent and significant change was observed in relative abundance of Ef18S rRNA (Fig. 6B), EfGam82 (Fig. 6C), and EfGam56 (Fig. 6D) expressed sequence tags in the IDO1−/−-derived caeca samples, when compared with the parental samples and also irrespective of the XA treatment. These results show that the aforementioned effect of host IDO and XA on the parasite life cycle is not mediated via their action on asexual or macrogametocyte development.

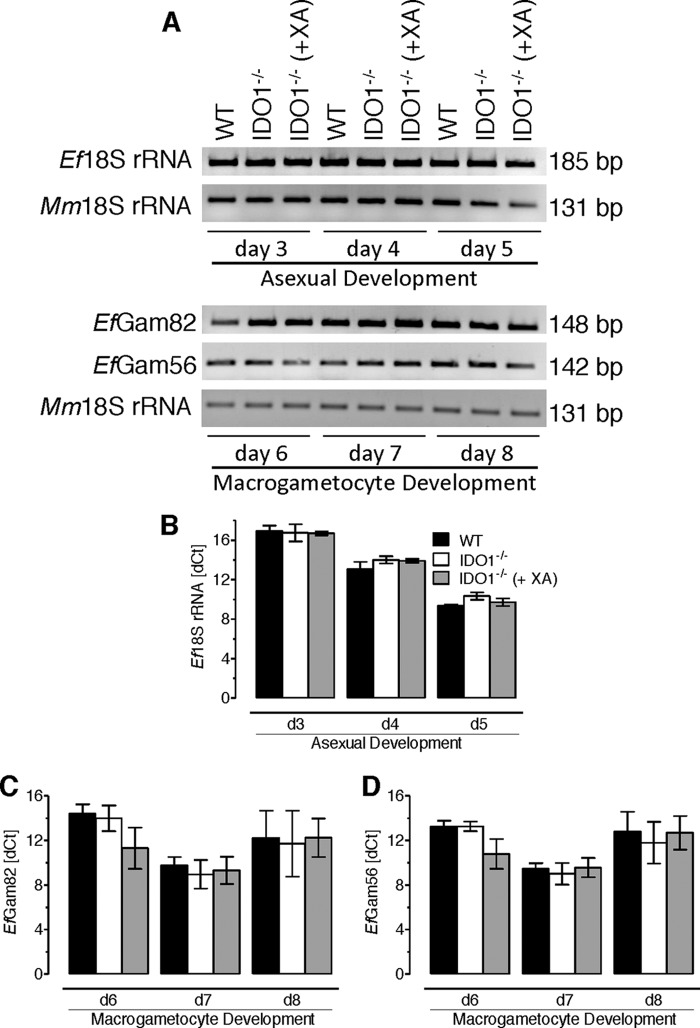

FIGURE 6.

Asexual and macrogametocyte development of E. falciformis are not influenced in IDO1−/− mice. The animals were infected with 1500 oocysts and treated with XA, as indicated. Total RNA derived from the parasitized caeca was subjected to quantitative PCR as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A, specific detection of the indicated parasite (Ef18S rRNA, EfGam82, and EfGam56) and host (Mm18S rRNA) expressed sequence tags by quantitative PCR followed by gel electrophoresis. B–D, to evaluate the abundance (dCt) of individual transcripts, Ef18S rRNA (B), EfGam82 (C), and EfGam56 (D) in each animal group, their Ct values were normalized to respective host samples (Mm18S rRNA). The error bars represent the means ± S.E. of two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

E. falciformis shows a strict tropism for epithelial cells in the mouse caecum, i.e., the parasite is host-, tissue-, and cell-specific. These features, along with its nonpathogenic nature for humans and a short life cycle, make this parasite a decent model for investigating localized host responses at the site of infection as also shown recently by Stange et al. (28). The parasite development in mouse, a well established model host, offers a particular advantage for identifying host determinants governing the parasite interactions. This work shows that induction of IDO1 is co-opted by E. falciformis for an efficient progression of its natural life cycle, demonstrating an unanticipated and conceptual exploitation of a key immune (IFNγ signaling) and a biochemical (kynurenine) pathway by an apicomplexan parasite.

Three enzymes can initiate the kynurenine pathway, degrading most of the cellular tryptophan into various metabolites collectively termed as kynurenines. IDO1 is constitutively expressed (4, 29, 30) and induced in a variety of cell types, e.g. dendritic cells, macrophages, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts (1, 5, 31, 32). The second enzyme, tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase, is expressed mainly in the liver, induced by the amino acid itself and regulates tryptophan homeostasis (33). Finally, IDO2, sharing ∼43% homology with IDO1, is present mainly in kidney, epididymis, testis, and liver (34). Unlike IDO1, IDO2 is not inducible by IFNγ and expressed despite the absence of cytokine in IFNγ-knock-out mice (34). Its function during infection is questionable. IFNγ, required for limiting parasitic infections including of Eimeria species (35–37), is a potent inducer of IDO1 (38–40). In line, expression of IDO1 is undetectable in the caeca of IFNγR knock-out mice parasitized with E. falciformis (not shown). In wild type mice, IDO1 expression is restricted to the caecum epithelium, probably because of strict tropism of E. falciformis for these host cells, and exerts a previously unanticipated beneficial effect on the in vivo parasite development.

In vivo blocking of IDO increases the burden of parasites such as T. gondii (18) and Trypanosoma cruzi (41) and of fungi (Candida albicans (42)) in mice, which seems consistent with its antimicrobial role in vitro. In contrast, inhibition or deficiency of enzyme during other parasitic (Leishmania donovani (18) and Trichuris muris (43)) and bacterial (Citrobacter rodentium (44)) infections reduced the pathogen burden in animals. Moreover, 1-MT, a competitive inhibitor of IDO, had none (herpes simplex virus 1) to a negative (BM5) influence on the virus replication in mice (18, 45), which occasionally differs with in vitro findings (46). Likewise, IDO1 as a positive determinant of Eimeria growth does not reconcile with canonical antimicrobial function, notwithstanding a potential depletion of tryptophan in the infected host cell. It must be noted that a fair comparison of different models is not feasible even within a parasite phylum (i.e., Apicomplexans) because of dissimilar setups, let alone with other pathogens as mentioned elsewhere. Typically, however, the in vivo function of IDO1 during infection with intracellular pathogens appears to be rather pathogen- and/or stage-specific.

Induction of IDO was shown to inhibit T-cell proliferation by a cell cycle arrest, anergy, and/or apoptotic events (5, 6, 14). The Eimeria-infected IDO1 knock-out mice, however, display a normal Th1 and IFNγ response, precluding their effects on the parasite growth in the transgenic animals. Instead, we show that a downstream metabolite of tryptophan degradation, XA, underlies the parasite development. XA is produced from 3-hydroxykynurenine as a by-product of detoxification process (47, 48). Importantly, it is known as a gametocyte-activating factor for Plasmodium that facilitates sexual development by promoting exflagellation of the male gametes in the mid-gut of mosquito (49). The restoration of the parasite growth in IDO1 knock-out mouse shows that host-derived xanthurenic acid is also required for an efficient progression of Eimeria, which is produced by the action of host IDO1 and associated enzymes of the kynurenine route. Accordingly, the development of Plasmodium species is impaired in the mosquito mutant (kh− Aedes aegypti), which lacks kynurenine 3-hydroxylase (50). Our data do not support the prospect that the asexual growth and macrogametocyte development of E. falciformis are influenced by IDO1 and XA. Therefore, we suggest that the effect of XA on E. falciformis development in mouse is similar to Plasmodium in mosquito host, i.e., on the maturation of male gametes. Exploitation of tryptophan catabolism by both apicomplexan parasites in their respective host appears to be evolutionarily conserved, despite a switch of two- to/from one-host life cycles. Whether Plasmodium species induce the only counterpart of mammalian IDO (i.e., tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase) in mosquito to co-opt the tryptophan catabolism remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

We thank Grit Meusel and Gabriele Drescher (Humboldt University, Berlin) for research assistance in parasite quantification and electron microscopy, respectively. We also thank Christoph Loddenkemper and Simone Spieckermann (Charité Medical School, Berlin) for contributions to immunohistochemical work.

This work was supported by fellowship and research grants from the Helmholtz Foundation to MS and from German Research Foundation (to N. G. and R. L.).

This article contains supplemental Table S1 and Figs. S1–S4.

- IDO

- indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase

- 1-MT

- 1-methyltryptophan

- KAT-II

- kynurenine aminotransferase II

- Kyn-3OH

- kynurenine 3-hydroxylase

- Ro61-8048

- 3,4-dimethoxy-N-[4-(3-nitrophenyl)-2-thiazolyl]benzenesulfonamide

- XA

- xanthurenic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1. Taylor M. W., Feng G. S. (1991) Relationship between interferon-γ, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, and tryptophan catabolism. FASEB J. 5, 2516–2522 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mellor A. L., Munn D. H. (2004) IDO expression by dendritic cells. Tolerance and tryptophan catabolism. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4, 762–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stone T. W., Darlington L. G. (2002) Endogenous kynurenines as targets for drug discovery and development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 1, 609–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Takikawa O., Yoshida R., Kido R., Hayaishi O. (1986) Tryptophan degradation in mice initiated by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 3648–3653 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Munn D. H., Shafizadeh E., Attwood J. T., Bondarev I., Pashine A., Mellor A. L. (1999) Inhibition of T cell proliferation by macrophage tryptophan catabolism. J. Exp. Med. 189, 1363–1372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hwu P., Du M. X., Lapointe R., Do M., Taylor M. W., Young H. A. (2000) Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase production by human dendritic cells results in the inhibition of T cell proliferation. J. Immunol. 164, 3596–3599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pfefferkorn E. R. (1984) Interferon γ blocks the growth of Toxoplasma gondii in human fibroblasts by inducing the host cells to degrade tryptophan. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 81, 908–912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Byrne G. I., Lehmann L. K., Landry G. J. (1986) Induction of tryptophan catabolism is the mechanism for γ-interferon-mediated inhibition of intracellular Chlamydia psittaci replication in T24 cells. Infect. Immun. 53, 347–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. MacKenzie C. R., Hucke C., Müller D., Seidel K., Takikawa O., Däubener W. (1999) Growth inhibition of multiresistant enterococci by interferon-γ-activated human uro-epithelial cells. J. Med. Microbiol. 48, 935–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Adams O., Besken K., Oberdörfer C., MacKenzie C. R., Rüssing D., Däubener W. (2004) Inhibition of human herpes simplex virus type 2 by interferon γ and tumor necrosis factor alpha is mediated by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Microbes Infect. 6, 806–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bodaghi B., Goureau O., Zipeto D., Laurent L., Virelizier J. L., Michelson S. (1999) Role of IFN-γ-induced indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and inducible nitric oxide synthase in the replication of human cytomegalovirus in retinal pigment epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 162, 957–964 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thomas S. M., Garrity L. F., Brandt C. R., Schobert C. S., Feng G. S., Taylor M. W., Carlin J. M., Byrne G. I. (1993) IFN-γ-mediated antimicrobial response. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-deficient mutant host cells no longer inhibit intracellular Chlamydia spp. or Toxoplasma growth. J. Immunol. 150, 5529–5534 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Munn D. H., Zhou M., Attwood J. T., Bondarev I., Conway S. J., Marshall B., Brown C., Mellor A. L. (1998) Prevention of allogeneic fetal rejection by tryptophan catabolism. Science 281, 1191–1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mellor A. L., Keskin D. B., Johnson T., Chandler P., Munn D. H. (2002) Cells expressing indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase inhibit T cell responses. J. Immunol. 168, 3771–3776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fallarino F., Grohmann U., Vacca C., Bianchi R., Orabona C., Spreca A., Fioretti M. C., Puccetti P. (2002) T cell apoptosis by tryptophan catabolism. Cell Death Differ. 9, 1069–1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Frumento G., Rotondo R., Tonetti M., Damonte G., Benatti U., Ferrara G. B. (2002) Tryptophan-derived catabolites are responsible for inhibition of T and natural killer cell proliferation induced by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. J. Exp. Med. 196, 459–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Terness P., Bauer T. M., Röse L., Dufter C., Watzlik A., Simon H., Opelz G. (2002) Inhibition of allogeneic T cell proliferation by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-expressing dendritic cells. Mediation of suppression by tryptophan metabolites. J. Exp. Med. 196, 447–457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Divanovic S., Sawtell N. M., Trompette A., Warning J. I., Dias A., Cooper A. M., Yap G. S., Arditi M., Shimada K., Duhadaway J. B., Prendergast G. C., Basaraba R. J., Mellor A. L., Munn D. H., Aliberti J., Karp C. L. (2012) Opposing biological functions of tryptophan catabolizing enzymes during intracellular infection. J. Infect. Dis. 205, 152–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stockdale P. G., Stockdale M. J., Rickard M. D., Mitchell G. F. (1985) Mouse strain variation and effects of oocyst dose in infection of mice with Eimeria falciformis, a coccidian parasite of the large intestine. Int. J. Parasitol. 15, 447–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schmatz D. M., Crane M. S., Murray P. K. (1984) Purification of Eimeria sporozoites by DE-52 anion exchange chromatography. J. Protozool. 31, 181–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pellicciari R., Rizzo R. C., Costantino G., Marinozzi M., Amori L., Guidetti P., Wu H. Q., Schwarcz R. (2006) Modulators of the kynurenine pathway of tryptophan metabolism. Synthesis and preliminary biological evaluation of (S)-4-(ethylsulfonyl)benzoylalanine, a potent and selective kynurenine aminotransferase II (KAT II) inhibitor. Chem. Med. Chem. 1, 528–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Röver S., Cesura A. M., Huguenin P., Kettler R., Szente A. (1997) Synthesis and biochemical evaluation of N-(4-phenylthiazol-2-yl)benzenesulfonamides as high-affinity inhibitors of kynurenine 3-hydroxylase. J. Med. Chem. 40, 4378–4385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Belli S. I., Ferguson D. J., Katrib M., Slapetova I., Mai K., Slapeta J., Flowers S. A., Miska K. B., Tomley F. M., Shirley M. W., Wallach M. G., Smith N. C. (2009) Conservation of proteins involved in oocyst wall formation in Eimeria maxima, Eimeria tenella and Eimeria acervulina. Int. J. Parasitol. 39, 1063–1070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carlin J. M., Ozaki Y., Byrne G. I., Brown R. R., Borden E. C. (1989) Interferons and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Role in antimicrobial and antitumor effects. Experientia. 45, 535–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mellor A. L., Chandler P., Baban B., Hansen A. M., Marshall B., Pihkala J., Waldmann H., Cobbold S., Adams E., Munn D. H. (2004) Specific subsets of murine dendritic cells acquire potent T cell regulatory functions following CTLA4-mediated induction of indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase. Int. Immunol. 16, 1391–1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zmarowski A., Wu H. Q., Brooks J. M., Potter M. C., Pellicciari R., Schwarcz R., Bruno J. P. (2009) Astrocyte-derived kynurenic acid modulates basal and evoked cortical acetylcholine release. Eur. J. Neurosci. 29, 529–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Miu J., Ball H. J., Mellor A. L., Hunt N. H. (2009) Effect of indoleamine dioxygenase-1 deficiency and kynurenine pathway inhibition on murine cerebral malaria. Int. J. Parasitol. 39, 363–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stange J., Hepworth M. R., Rausch S., Zajic L., Kühl A. A., Uyttenhove C., Renauld J. C., Hartmann S., Lucius R. (2012) IL-22 mediates host defense against an intestinal intracellular parasite in the absence of IFN-γ at the cost of Th17-driven immunopathology. J. Immunol. 188, 2410–2418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shimizu T., Nomiyama S., Hirata F., Hayaishi O. (1978) Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Purification and some properties. J. Biol. Chem. 253, 4700–4706 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yoshida R., Nukiwa T., Watanabe Y., Fujiwara M., Hirata F., Hayaishi O. (1980) Regulation of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activity in the small intestine and the epididymis of mice. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 203, 343–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Grohmann U., Bianchi R., Belladonna M. L., Silla S., Fallarino F., Fioretti M. C., Puccetti P. (2000) IFN-γ inhibits presentation of a tumor/self peptide by CD8 α-dendritic cells via potentiation of the CD8α+ subset. J. Immunol. 165, 1357–1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fallarino F., Vacca C., Orabona C., Belladonna M. L., Bianchi R., Marshall B., Keskin D. B., Mellor A. L., Fioretti M. C., Grohmann U., Puccetti P. (2002) Functional expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase by murine CD8 α(+) dendritic cells. Int. Immunol. 14, 65–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Salter M., Pogson C. I. (1985) The role of tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase in the hormonal control of tryptophan metabolism in isolated rat liver cells. Effects of glucocorticoids and experimental diabetes. Biochem. J. 229, 499–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ball H. J., Sanchez-Perez A., Weiser S., Austin C. J., Astelbauer F., Miu J., McQuillan J. A., Stocker R., Jermiin L. S., Hunt N. H. (2007) Characterization of an indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-like protein found in humans and mice. Gene 396, 203–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shi Y. F., Mahrt J. L., Mogil R. J. (1989) Kinetics of murine delayed-type hypersensitivity response to Eimeria falciformis (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae). Infect. Immun. 57, 146–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rose M. E., Hesketh P., Wakelin D. (1992) Immune control of murine coccidiosis. CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes contribute differentially in resistance to primary and secondary infections. Parasitology. 105, 349–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rose M. E., Wakelin D., Hesketh P. (1991) Interferon-γ-mediated effects upon immunity to coccidial infections in the mouse. Parasite Immunol. 13, 63–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Silva N. M., Rodrigues C. V., Santoro M. M., Reis L. F., Alvarez-Leite J. I., Gazzinelli R. T. (2002) Expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, tryptophan degradation, and kynurenine formation during in vivo infection with Toxoplasma gondii. Induction by endogenous γ interferon and requirement of interferon regulatory factor 1. Infect. Immun. 70, 859–868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fujigaki S., Saito K., Takemura M., Maekawa N., Yamada Y., Wada H., Seishima M. (2002) l-tryptophan-l-kynurenine pathway metabolism accelerated by Toxoplasma gondii infection is abolished in γ interferon-gene-deficient mice. Cross-regulation between inducible nitric oxide synthase and indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase. Infect. Immun. 70, 779–786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rottenberg M. E., Gigliotti Rothfuchs A., Gigliotti D., Ceausu M., Une C., Levitsky V., Wigzell H. (2000) Regulation and role of IFN-γ in the innate resistance to infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae. J. Immunol. 164, 4812–4818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Knubel C. P., Martínez F. F., Fretes R. E., Díaz Lujan C., Theumer M. G., Cervi L., Motrán C. C. (2010) Indoleamine 2,3-dioxigenase (IDO) is critical for host resistance against Trypanosoma cruzi. FASEB J. 24, 2689–2701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bozza S., Fallarino F., Pitzurra L., Zelante T., Montagnoli C., Bellocchio S., Mosci P., Vacca C., Puccetti P., Romani L. (2005) A crucial role for tryptophan catabolism at the host/Candida albicans interface. J. Immunol. 174, 2910–2918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bell L. V., Else K. J. (2011) Regulation of colonic epithelial cell turnover by IDO contributes to the innate susceptibility of SCID mice to Trichuris muris infection. Parasite Immunol. 33, 244–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Harrington L., Srikanth C. V., Antony R., Rhee S. J., Mellor A. L., Shi H. N., Cherayil B. J. (2008) Deficiency of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase enhances commensal-induced antibody responses and protects against Citrobacter rodentium-induced colitis. Infect. Immun. 76, 3045–3053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hoshi M., Saito K., Hara A., Taguchi A., Ohtaki H., Tanaka R., Fujigaki H., Osawa Y., Takemura M., Matsunami H., Ito H., Seishima M. (2010) The absence of IDO upregulates type I IFN production, resulting in suppression of viral replication in the retrovirus-infected mouse. J. Immunol. 185, 3305–3312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Adams O., Besken K., Oberdörfer C., MacKenzie C. R., Takikawa O., Däubener W. (2004) Role of indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase in α/β and γ interferon-mediated antiviral effects against herpes simplex virus infections. J. Virol. 78, 2632–2636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Okuda S., Nishiyama N., Saito H., Katsuki H. (1996) Hydrogen peroxide-mediated neuronal cell death induced by an endogenous neurotoxin, 3-hydroxykynurenine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 12553–12558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wei H., Leeds P., Chen R. W., Wei W., Leng Y., Bredesen D. E., Chuang D. M. (2000) Neuronal apoptosis induced by pharmacological concentrations of 3-hydroxykynurenine. Characterization and protection by dantrolene and Bcl-2 overexpression. J. Neurochem. 75, 81–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Billker O., Lindo V., Panico M., Etienne A. E., Paxton T., Dell A., Rogers M., Sinden R. E., Morris H. R. (1998) Identification of xanthurenic acid as the putative inducer of malaria development in the mosquito. Nature 392, 289–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Arai M., Billker O., Morris H. R., Panico M., Delcroix M., Dixon D., Ley S. V., Sinden R. E. (2001) Both mosquito-derived xanthurenic acid and a host blood-derived factor regulate gametogenesis of Plasmodium in the midgut of the mosquito. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 116, 17–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]