Background: The role of plastidic thioredoxins (Trxs) is extensive in chlorophyta, whereas it is unknown in other plants.

Results: Diatom plastidic Trxs participate in the reductive activation of pyrenoidal carbonic anhydrases.

Conclusion: One of the targets of Trxs in diatom plastids is a carbon flow control.

Significance: The first direct evidence for the function of plastidic Trxs in marine diatoms.

Keywords: Carbon Dioxide, Chloroplast, Photosynthesis, Redox Regulation, Thioredoxin, Carbonic Anhydrase, Marine Diatom, Pyrenoid

Abstract

Thioredoxins (Trxs) are important regulators of photosynthetic fixation of CO2 and nitrogen in plant chloroplasts. To date, they have been considered to play a minor role in controlling the Calvin cycle in marine diatoms, aquatic primary producers, although diatoms possess a set of plastidic Trxs. In this study we examined the influences of the redox state and the involvement of Trxs in the enzymatic activities of pyrenoidal carbonic anhydrases, PtCA1 and PtCA2, in the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. The recombinant mature PtCA1 and -2 (mPtCA1 and -2) were completely inactivated following oxidation by 50 μm CuCl2, whereas DTT activated CAs in a concentration-dependent manner. The maximum activity of mPtCAs in the presence of 6 mm reduced DTT increased significantly by addition of 10 μm Trxs from Arabidopsis thaliana (AtTrx-f2 and -m2) and 5 μm Trxs from P. tricornutum (PtTrxF and -M). Analyses of mPtCA activation by Trxs in the presence of DTT revealed that the maximum mPtCA1 activity was enhanced ∼3-fold in the presence of Trx, whereas mPtCA2 was only weakly activated by Trxs, and that PtTrxs activate PtCAs more efficiently compared with AtTrxs. Site-directed mutagenesis of potential disulfide-forming cysteines in mPtCA1 and mPtCA2 resulted in a lack of oxidative inactivation of both mPtCAs. These results reveal the first direct evidence of a target of plastidic Trxs in diatoms, indicating that Trxs may participate in the redox control of inorganic carbon flow in the pyrenoid, a focal point of the CO2-concentrating mechanism.

Introduction

Redox regulation plays an important role in a number of biological processes such as photosynthetic-carbon reduction via the Calvin cycle, nitrogen metabolism, fatty acid biosynthesis, carbohydrate storage and translation. Present in all living cells (1), the thioredoxin (Trx)2 family is a major protein disulfide reducing system. Chloroplasts of algae and land plants generally possess the ferredoxin (Fd)/Trx system (2). Enzymes like the ferredoxin-thioredoxin reductase play a central role in this system by transferring electrons from the photosynthetic transport chain to Trxs. Trxs are small proteins, which possess two cysteine residues that are capable of forming intramolecular disulfide bonds within a conserved WC(G/P)PC motif. The two cysteines in this motif can be reversibly reduced in the light by ferredoxin-thioredoxin reductase and oxidized by reducing target enzymes, thus modulating their enzymatic activities (3). Plant genomes contain numerous Trx genes. For example, at least 20 Trx isoforms have been identified in Arabidopsis thaliana (4). Trx isoforms can be grouped into seven subfamilies denoted Trx f, h, m, o, x, y, and z based on their primary structures (5, 6). Trxs f, m, x, y, and z are localized in the chloroplast, whereas Trx o is located in the mitochondrion (5, 7, 8). Trx h can be found in multiple cell compartments: cytosol, nucleus, ER, and mitochondria (8).

Affinity chromatography using the mutated Trx as an immobilized ligand has revealed the presence of more than 300 Trx-interacting proteins, including numerous chloroplastic factors of unknown function in land plants and green algae (9–11). A chloroplastic β-carbonic anhydrase (CA) is also known to be activated by reduction by Trx and/or glutaredoxin (12, 13) in the chloroplast of higher plants (10, 14, 15). These results strongly suggest that redox regulation via Trxs in the plant plastid processes involves an unexpectedly high number of target enzymes. In contrast, little is known about redox regulation in the plastids of chromalveolates, a large supergroup including major primary producers in aquatic environments. For instance, in diatoms eight genes have been found to encode a set of Trxs in the genome of Phaeodactylum tricornutum, and at least three Trx candidates (f, m, and y) are located in the chloroplast, together with an ferredoxin-thioredoxin reductase gene (16) (supplemental Fig. S1 shows a sequence comparison of two of the diatom plastid Trxs, f and m to those of A. thaliana). In diatoms, the regulatory properties of several key enzymes in the Calvin cycle have been investigated in relationship to redox state, but none of them appear to be regulated by Trxs. An exception, the reductive activation of fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase has been confirmed in the stromal extracts of diatom plastids (17). Furthermore, it was found that the activity of chloroplastic phosphoglycerate kinase from P. tricornutum is dependent on the redox state (18). Taken together, this evidence strongly suggests that the Calvin cycle in diatoms (and most probably the closely related algae among the chromalveolate supergroup) is largely independent of redox regulation by Trxs. It is thus likely that chloroplastic Trx systems in diatoms and in other chromophytic algae have undergone a unique functional specialization. However, the main targets of redox controls by Trxs in the chloroplast of diatoms remain poorly understood.

Marine diatoms are known to be responsible for about one-fifth of global primary production, playing a crucial role in the global cycle of inorganic elements (19, 20). To overcome difficulties in acquiring CO2 in the alkaline and saline marine environment, diatoms possess CO2-concentrating mechanisms (CCM), which probably includes active uptake systems for HCO3− and CO2 (21–24). It has also been suggested that C4 metabolism additionally participates in the CCM of the marine diatom, Thalassiosira weissflogii (25), although the general occurrence of such hybrid-type CCM in diatoms is yet to be clarified. CCMs in marine diatoms are controlled by environmental CO2 concentrations (26, 27), strongly suggesting the importance of activity control of CCM in response to the availability of CO2.

Intracellular CAs are known to play an important role in the flux control of inorganic carbon in the process of CCMs in cyanobacteria (28, 29) and the alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (30, 31). In particular, the occurrence of internal CA close to the CO2 fixation enzyme, ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco), and/or the interior of the thylakoid has been suggested to be essential for the growth of cyanobacteria and green algae under CO2 limiting conditions (30–32). Genomes of the marine diatoms Thalassiosira pseudonana and P. tricornutum (33–34) contain at least 13 and 9 putative CA sequences, respectively (35), and two β-type CAs in P. tricornutum are so far identified as CAs (36, 37). Δ- and ζ-type CAs in T. pseudonana revealed very similar primary sequences in the active sites compared with δ- and ζ-CAs identified in the marine diatom T. weissflogii (38, 39). β-CAs in P. tricornutum denoted as PtCA1 and -2, have been found to be localized to the pyrenoid of P. tricornutum (35) and the transcription of their genes, ptca1 and ptca2, are known to be repressed by elevated CO2, presumably via a process mediated by cytosolic cAMP concentrations as a second messenger (26). The localization of these CAs at the pyrenoid and the fact that they are up-regulated under limited CO2 concentrations strongly suggests the function of PtCA1 and -2 as components involved in the last step of flow controls of inorganic carbon toward CO2 fixation by Rubisco in the pyrenoid, under CO2 limitation (26, 40).

The activity of PtCAs are thus an interesting pre-reaction of the Calvin cycle in the plastids of marine diatoms and their post-translational control in response to the physiological state of the plastid is a key process that may directly affect oceanic primary production. As an initial attempt to elucidate the targets of the Trx system in diatom chloroplasts, in the present study, we have examined the regulatory mechanisms of activity of pyrenoidal PtCA1 and -2 in the marine diatom P. tricornutum.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression and Purification of Mature PtCA1 and -2

Previously determined mature sequences of PtCA1 (GenBankTM accession number AAL07493, 47 to 283 amino acid relative to the initial methionine) (37) and the putative mature region of PtCA2 (GenBank accession number BAD67442, 42 to 274 amino acids relative to the initial methionine), which was estimated from the nucleotide sequence of PtCA1, were used in this study. cDNA fragments encoding mature PtCA1 (mPtCA1) and mature PtCA2 (mPtCA2) were amplified by PCR using PrimeStar (Takara, Japan) with a forward and reverse primer set, mPtCA1FwNdeI (5′-GGAATTCCATATGGCTGGCGG-3′) and ptca1(-taa)RvXhoI (5′-CCGCTCGAGGGCAGGGATCTTGGC-3′) for mptca1 and PtCA2-NdeI-FW (5′-GGAATTCCATATGGCGGCCAAAGGCGGCTACGAT-3′) and PtCA2(-TAG)-XhoI-RV (5′-CCGCTCGAGCATGGGGACCTTGGC-3′) for mptca2, which are attached at their 5′ termini to the NdeI and XhoI sites, respectively. These fragments were digested with NdeI and XhoI and ligated into the NdeI and XhoI sites of the pET21a expression vector (Novagen, Germany). The resulting expression vector containing mptca1 (pET21a-mPtCA1:His6) was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) and the vector containing mptca2 (pET21a-mPtCA2:His6) was transformed into E. coli KRX (Promega). Transformed E. coli cells were cultured at 37 °C until A600 of 0.6 was reached. Expression of mPtCA1 and mPtCA2 was initiated by the addition of 1 mm isopropyl 1-thio-d-galactopyranoside (Wako) and 0.1% d-rhamnose (Wako), and the induction treatments were continued for the next 20 h at 20 °C. E. coli cells in 1000 ml of culture were then harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 10 min and the cell pellet was resuspended in binding buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 500 mm NaCl, 5 mm imidazole). Cells were disrupted by high pressure homogenizer, EmulsiFlex-C5 (AVESTIN, Canada) at 15,000 p.s.i. at 4 °C for 15 min. The cell lysate was centrifuged at 30,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C and the supernatant was then applied to a Ni-SepharoseTM 6 Fast Flow (GE Healthcare) column (ϕ10 × 40 mm), which was pre-equilibrated with binding buffer. The column was washed with binding buffer until the absorbance at 280 nm (A280) of nonadsorbed fractions became less than 0.05, followed by the addition of washing buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 500 mm NaCl, 50 mm imidazole) until the A280 of the fraction became less than 0.02. The His tag fusion protein was then eluted with elution buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 500 mm NaCl, 500 mm imidazole). The protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad) using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard. Purity of eluted protein was assessed by SDS-PAGE (supplemental Fig. S2).

Trx Constructs and Purification of Trxs

Genes for AtTrxs were obtained by RT-PCR with the following oligonucleotide primers: AtTrxm2-NdeI-Fw (5′-GGAATTCCATATGGAAACTACTACCGATATTCA-3′) and AtTrxm2-XhoI-Rv (5′-CCGCTCGAGTCATGGCAAGAACTTGTCGA-3′) for AtTrxm2 (GenBank accession number AEE82333) and AtTrxf2-NdeI-Fw (5′-GGATTCCATATGGAAACAGTGAATGTCACTG-3′) and AtTrxf2-XhoI-Rv (5′-CCGCTCGAGTCAGCCTGACCTTGCTGCTT-3′) for AtTrxf2 (GenBank accession number AED92288). In the case of AtTrxf2, the His6 tag was fused at the C terminus. Total RNA isolated from A. thaliana (41) was used as a template. The amplified DNA fragments were cloned into NdeI and XhoI sites of pET23a (Novagen). These expression vectors were transformed into E. coli strain BL21(DE3), and transformed cells were cultured at 37 °C until the A600 reached 0.7. Expression was induced by the addition of 1 mm isopropyl 1-thio-d-galactopyranoside, followed by a further culture at 25 °C for 16 h. All purification procedures were performed at 4 °C. Overexpressed AtTrx-m2 was purified as follows. E. coli cells were suspended in buffer A (25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, with 0.5 mm DTT to prevent undesired disulfide bond formation) and disrupted by sonication. The disrupted cells were centrifuged at 125,000 × g for 30 min, and the supernatant (crude extract) was applied into a DEAE-TOYOPERAL 650M column (Tosoh), which was pre-equilibrated with buffer A. Proteins were eluted with a 0–300 mm linear gradient of NaCl in buffer A. The peak fractions containing AtTrx-m2 were collected and ammonium sulfate was added to a final concentration of 30% (w/v). This protein sample was applied for the Butyl-TOYOPEARL 650M column (Tosoh) and eluted with a 30 to 0% inverse ammonium sulfate gradient.

AtTrx-f2 expressed in E. coli was purified as follows. The crude extract was obtained as described above and applied to a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid column that was pre-equilibrated with 25 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). After washing with 50 mm imidazole in Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), the proteins were eluted with 200 mm imidazole in 25 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). The eluted protein sample was supplemented in DTT and ammonium sulfate to final concentrations of 0.5 mm and 30% (w/v), respectively, and applied to a Butyl-TOYOPEARL column. Protein was then eluted with a 30–0% inverse ammonium sulfate linear gradient in buffer A. The purified Trxs were ultrafiltrated to remove ammonium sulfate using Amicon Ultra-15 (cut-off molecular weight, 5,000; Millipore) prior to biochemical analysis.

cDNA fragments encoding PtTrxF (JGI Protein ID 46280) and PtTrxM (JGI Protein ID 51357) were amplified by PCR using a cDNA library of P. tricornutum as a template (primers Pt_trxf-Fw, 5′-AAAGTACATATGCCGCCTTTGACCTTGTC-3′, Pt_trxf-Rv, 5′-CATCGTCGCCCGGGATCCTAAC-3′, Pt_trxm-Fw, 5′-CCACGGCATATGATGGCAGTTG, Pt_trxm-Rv, 5′-CCGCCGACTCGAGAGCACC-3′). The ptTrxF fragment was digested with NdeI and BamHI and ligated into the NdeI and BamHI sites of pET28a (Novagen). The ptTrxM fragment was digested with NdeI and XhoI and ligated into the NdeI and XhoI sites of pET28a. The vector containing the ptTrxF gene was transformed into E. coli KRX and that containing the ptTrxM gene was transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3). Transformed E. coli cells were cultured at 37 °C until an A600 of 0.6 was reached. Expressions of PtTrxF and PtTrxM were initiated, respectively, by the addition of 0.1% d-rhamnose and 1 mm isopropyl 1-thio-d-galactopyranoside, and induction treatments were continued for the next 4 h at 37 °C. Purification of expressed PtTrxs was carried out as described in the purification of PtCAs.

Measurement of CA Activity

CA activity was measured by a potentiometric method as described by Wilbur and Anderson (42) with some modifications. 20 μl of CA solution was added to 1.48 ml of 20 mm barbital buffer (pH 8.4) in a water-jacketed acrylic chamber maintained at 2 °C. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 0.5 ml of ice-cold CO2-saturated water and the time required for the pH to drop from 8.3 to 8.0 was determined. The activity of CA was calculated as Wilbur-Anderson units (WAU) according to Equation 1,

where T0 and T are the time required for the pH drop in the absence and presence of CA, respectively.

Oxidation and Reduction of Recombinant mPtCAs

Given that the initial redox state of recombinant mPtCAs purified from E. coli was not clear, the protein was once oxidized by incubation with 50 μm CuCl2 in Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) for 1 h at 20 °C. CuCl2 was then removed by dialysis with 1000 volumes of 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) by using dialysis membrane 8/25 three times (Sanko Junyaku, Japan). For in vitro reduction, 5 μm mPtCA1 or -2 was incubated for 1 h at 20 °C with 6 mm DTT in Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) in the absence or presence of 10 μm AtTrxs or 5 μm PtTrxs. In some experiments, 5 μm of the purified mPtCAs protein was activated by reduction with 5 μm PtTrxF and 6 mm DTT in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) for 1 h at 20 °C, and the protein was degassed by aspiration for 15 min. Degassed mPtCAs was re-aerated for 5 min by pure N2 (0% O2), atmospheric air (21% O2), 49% O2 or pure O2 (100%) at 20 °C, and then incubated for 1 h at 20 °C. The degassed mPtCAs was alternatively treated with 100 μm H2O2, 2 mm oxidized glutathione (GSSG), or 500 μm dehydroascorbate for 1 h at 20 °C. After these redox treatments, mPtCAs were subjected to measurement of CA activity and SDS-PAGE.

Site-directed Mutagenesis of Cys Residues in mPtCA1 and mPtCA2

Mutations to Cys-105 or -166 into Ser residue were introduced to mptca1 by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis using primers mPtCA1-C105S-Fw (5′-CCCGCACGTTATCGTCTCTGGTCACTATGAATG-3′) and mPtCA1-C105S-Rv (5′-CATTCATAGTGACCAGAGACGATAACGTGCGGG-3′) for C105S and mPtCA1-C166S-Fw (5′-GAACGTGATCGAACAGTCCGTAAACCTGTACAAG-3′) and mPtCA1-C166S-Rv (5′-CTTGTACAGGTTTACGGACTGTTCGATCACGTTC-3′) for C166S mutations. Cys/Ser mutations to Cys-102 or -163 in mptca2 were done using primers PtCA2-C102S-Fw (5′-CAACGTAATCCTGTCTGGACACTACGAATG-3′) and PtCA2-C102S-Rv (5′-CATTCGTAGTGTCCAGACAGGATTACGTTG-3′) for C102S and PtCA2-C163S-Fw (5′-GAACGTCATTGAACAATCCGTCAACCTCTT-3′) and PtCA2-C163S-Rv (5′-AAGAGGTTGACGGATTGTTCAATGACGTTC-3′) for C163S mutations. The resulting site-directed constructs for mPtCA1 and -2 were packaged into a pET21a vector. Mutated PtCAs were synthesized in E. coli and purified as described above.

Analyses of PtCAs Activity under Different Reducing Conditions

5 μm Oxidized mPtCA1 or -2 was incubated for 1 h at 20 °C with 0.01–30 mm DTT in Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) in the absence or presence of adequate concentrations of Trxs, or with 0.25 to 20 μm Trxs in the absence or presence of adequate concentrations of DTT. Concentrations of DTT and Trxs are indicated in each experimental result. After reducing treatment, CA activity was measured by a potentiometric method as described above.

Apparent Molecular Weight Analysis of Reduced and Oxidized Forms of PtCAs

The apparent molecular weight of wild-type and mutated mPtCAs for the reduced or oxidized forms was determined by reducing and nonreducing SDS-PAGE using a 12% polyacrylamide gel (43), which was then followed by Western blot analysis using anti-PtCAs rabbit antiserum. Calculated apparent molecular masses of purified mPtCA1 and mPtCA2 are 27.5 and 26.9 kDa, respectively (supplemental Fig. S2). Samples for reducing SDS-PAGE were mixed with an equal volume of sample buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 10% glycerol, 2% SDS, 0.1% bromophenol blue, and 5% 2-mercaptoethanol) and incubated for 5 min at 96 °C. Samples for nonreducing SDS-PAGE were mixed with an equal volume of the sample buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 10% glycerol, 2% SDS and 0.1% bromophenol blue) and incubated for 15 min at 37 °C. Following SDS-PAGE, protein was blotted onto PVDF membrane (Immobilon-P, Millipore, MA), blocked in 1% BSA, and a Western blot was performed with anti-PtCAs rabbit antiserum diluted 5,000 times with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.2). The location of the anti-PtCA1 antibody was visualized by chemiluminescent reaction with a secondary antibody coupled with horseradish peroxidase (anti-rabbit IgG HRP, Promega, WI), hydrogen peroxide, and luminol using ImmobilonTM Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore).

MALDI-TOF Peptide-mapping Analysis

To determine the disulfide partner cysteines, reduced or oxidized proteins were alkylated with 50 mm iodoacetamide in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) at room temperature for 1 h in the dark. Carboxyamidomethylated proteins were digested with trypsin in 50 mm NH4HCO3 at 37 °C overnight, using an enzyme/substrate ratio of 1:100 (w/w). MALDI mass spectra were recorded using a UltraFLEX MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, MA). Peptide mixtures were loaded on the MALDI target, using 3,5-dimethoxy-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (Tokyo Chemical Industry Co.) as matrix. Internal mass calibration was performed with Peptide calibration standard (Bruker Daltonics). Spectra were acquired in linear mode, elaborated using FlexAnalysis (Bruker Daltonics).

Sequence Alignment of PtCAs with β-CAs from Other Origins

Full sequences of different β-CAs were compared by using the ClustalW2 program (44) with the slow setting. PtCA1 and PtCA2 were compared with the identified or putative β-CA sequences from Ectocarpus siliculosus (GenBank accession number CBN77745), Phytophthora infestans (GenBank accession number EEY58070), Soridaria macrospora (GenBank accession number CAT00781), Aspergillus clavatus (GenBank accession number EAW12033), Flavobacteria bacterium (GenBank accession number EAS18913), Neisseria mucosa (GenBank accession number EFC87000), E. coli (Swiss-Prot accession number P61517), Coccomyxa (GenBank accession number AAC33484), chloroplastic form of A. thaliana (Swiss-Prot accession number P27140), and chloroplastic form of spinach (Swiss-Prot accession number P16016).

Modeling of Three-dimensional Structure of PtCAs

Tertiary structures of mPtCA1 and mPtCA2 were predicted by LOOPP (45) and visualized by Chimera. Based on sequence similarity, LOOPP identified closely related homologous proteins and extracted their structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) data base. Then, using each of the top five identified structures as templates, LOOPP generated five structural models for PtCAs. Predictions were made with 60–268 amino acids and 52–272 amino acids relative to the first N-terminal residues of mPtCA1 and mPtCA2, respectively. In the present study, the model was constructed based on the β-CA structure of E. coli (PDB code 1I6P).

Phylogenetic Analysis of β-CAs

For construction of phylogenetics trees of β-CAs, PtCA1 and PtCA2 were aligned with the β-CAs from bacteria, fungi, and stramenopiles using ClustalW2 as described above. Maximum likelihood analysis was done at PhyML (46); phylogenetic calculation was initiated with a neighbor-joining tree (BIONJ) was computed by the program PhyML. The fast algorithm performing Nearest Neighbor Interchanges was used to improve a reasonable starting tree topology. The amino acid replacement matrix LG was selected with four substitution rate categories. Bootstrap analyses with 100 replicates were performed. The resulting tree was imported into FigTree version 1.3.1.

RESULTS

Redox Sensitivity of Recombinant mPtCA1 and mPtCA2

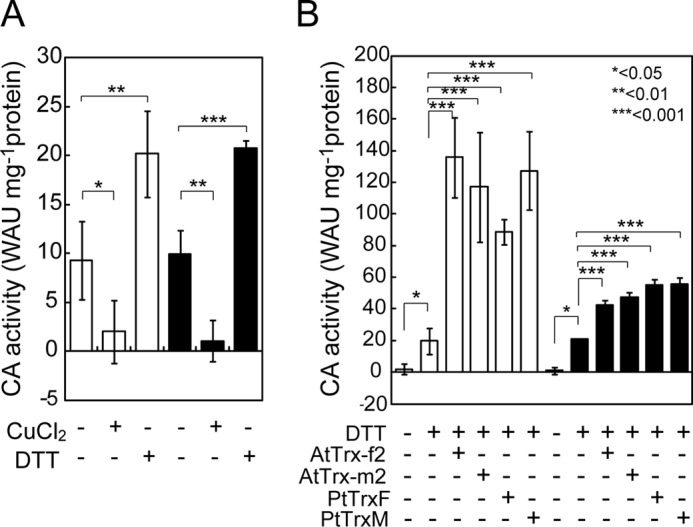

We first examined whether or not the enzymatic activity of recombinant His6 fusion of mPtCAs is affected by changes in the redox state. Recombinant mPtCA1 purified from E. coli (supplemental Fig. S2) exhibited CA activity of about 10 WAU mg−1 of protein (Fig. 1A). The CA activity was efficiently suppressed by a 1-h treatment with 50 μm CuCl2 and increased to about 20 WAU mg−1 of protein by a 1-h treatment with 6 mm DTT (Fig. 1A), but was not activated by treatment with Trx in the absence of DTT (supplemental Fig. S3A). The recombinant mPtCA1 protein seemed to be partially oxidized during purification. The same tendency was also observed in redox controls of recombinant mPtCA2 (Fig. 1A). Upon reduction of oxidized mPtCA1 by incubation with 6 mm DTT for 1 h, enzyme activity was restored to about 20 WAU mg−1 of protein (Fig. 1B), an equal level to the previous DTT-treated mPtCA1 (Fig. 1A), indicating that mPtCA1 could be reversibly inactivated and activated depending on the redox state. Co-incubation of 10 μm AtTrx-f2 or AtTrx-m2, or 5 μm PtTrxF or PtTrxM with 6 mm DTT in the reducing treatment revealed drastic stimulations (up to 6–7-fold) of mPtCA1 activity (120–140 WAU mg−1 of protein) compared with DTT treatment alone (Fig. 1B). CA activity reached a maximum after 15 min of reduction (supplemental Fig. S3B). In contrast to mPtCA1, stimulation of mPtCA2 activity by the addition of 10 μm AtTrx-f2 or AtTrx-m2, or 5 μm PtTrxF or PtTrxM in the presence of 6 mm DTT was only about 2-fold compared with DTT alone (Fig. 1B). The nontagged form of PtCA1 showed little difference in the profile of the redox control of CA activity from that observed in the His-tagged form of mPtCA1 (supplemental Fig. S3, C and D), indicating the irrelevance of C-terminal His6 to CA activity and its redox control. The His-tagged forms of PtCA were therefore used in subsequent experiments.

FIGURE 1.

Redox sensitivity of recombinant mPtCA1 (open bar) and mPtCA2 (closed bar). A, activities of purified recombinant PtCAs treated with 50 μm CuCl2 or 6 mm DTT for 1 h at 20 °C. B, PtCAs oxidized by 50 μm CuCl2 were reduced by 6 mm DTT in the absence or presence of different types of Trxs for 1 h at 20 °C. 10 μm AtTrx-f2/-m2 and 5 μm PtTrxF/M were used. Values are mean ± S.D. of three duplicates. Statistical significance was determined by t test (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001).

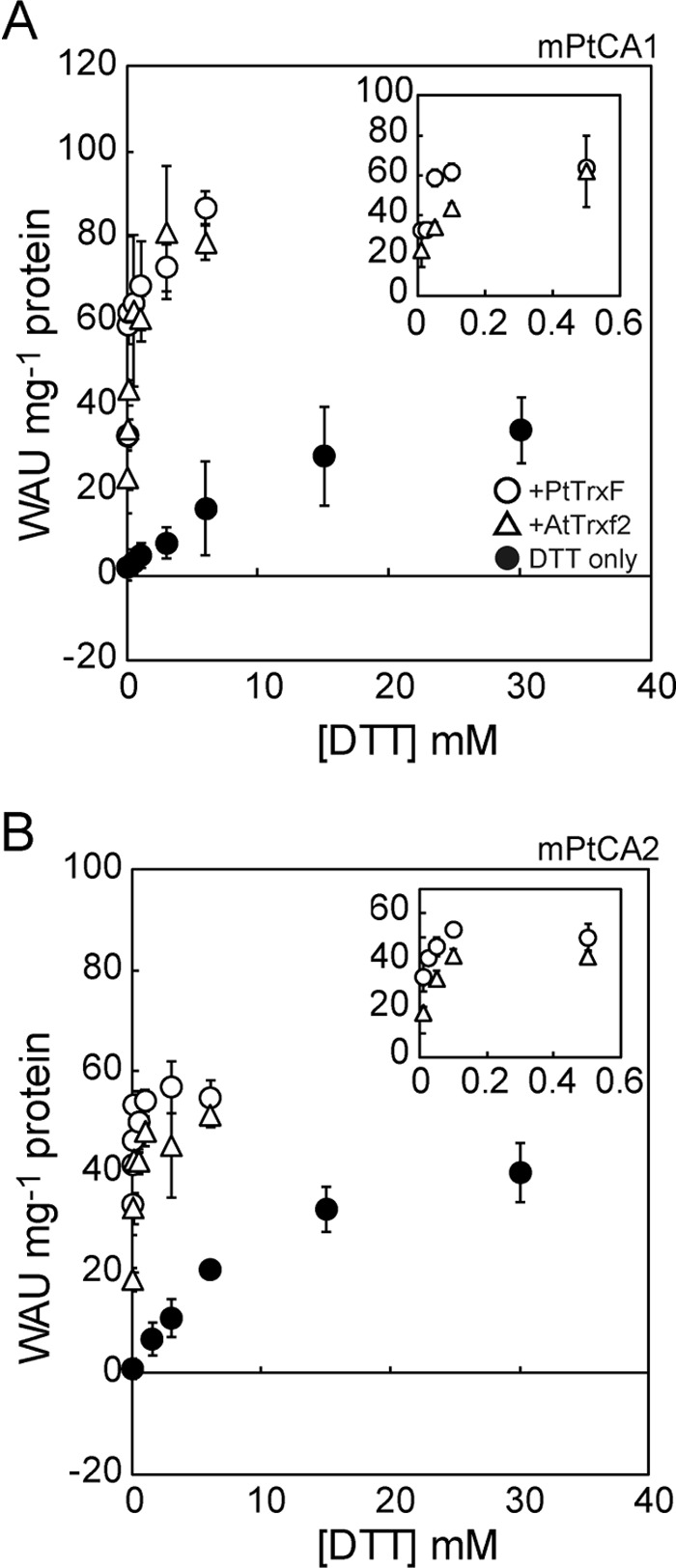

DTT-dependent Activation of mPtCAs

To analyze the biochemical characteristics of interaction between oxidized mPtCAs and DTT in the absence or presence of Trx, mPtCAs were initially oxidized by 50 μm CuCl2 for 1 h and then incubated with various concentrations of DTT in the absence or presence of 10 μm AtTrxs or 5 μm PtTrxs. The activity of mPtCA1 was increased as a function of DTT concentration and was saturated at concentrations of 20–30 mm DTT (Fig. 2A). The maximum activity of mPtCA1 was greatly increased by addition of AtTrx-f2 or PtTrxF and the concentration of DTT required to reactivate PtCA1 in the presence of Trxs decreased by an order of magnitude compared with DTT treatment alone, presumably because Trx mediated transfer of the electrochemical potential from DTT to mPtCA1 very efficiently (Fig. 2A). Comparable results were also observed with AtTrx-m2 and PtTrxM (supplemental Fig. S4). Similarly to mPtCA1, mPtCA2 was activated by DTT in a concentration-dependent manner with saturation at about 20–30 mm DTT (Fig. 2B). The efficiency of activation of mPtCA2 by DTT in the presence of Trx was also greatly improved by an order of magnitude compared with DTT treatment alone (Fig. 2B and supplemental Fig. S4). However, in contrast to mPtCA1, Trxs did not significantly stimulate the maximum mPtCA2 activity (Fig. 2B and supplemental Fig. S4). Half-saturation concentrations of DTT (S0.5[DTT]) of mPtCA1 and -2 were calculated, respectively, to be 10.8 and 8.6 mm in the absence of Trxs, but decreased, respectively, to 56.3 and 16.9 μm in the presence of 10 μm AtTrx-f2, 49.5 and 44.6 μm with 10 μm AtTrx-m2, 14.2 and 6.5 μm with 5 μm PtTrxF, and 14.0 and 14.4 μm with 5 μm PtTrxM (Table 1). These data reveal that PtCAs are reduced by Trxs efficiently and that PtTrxs are more efficient than AtTrxs in the process. The maximum activity (WAUmax) of mPtCA1 was increased to about 100 WAU mg−1 of protein in the presence of all Trxs, whereas those in mPtCA2 were relatively stable at around 50 WAU mg−1 of protein (Fig. 2 and Table 1). The level of WAUmax was apparently independent of the type of Trxs.

FIGURE 2.

Kinetics of DTT-dependent activation of mPtCAs. A, 5 μm mPtCA1 was initially oxidized by 50 μm CuCl2 and then incubated with various concentrations of DTT for 1 h at 20 °C. CA activity was plotted as a function of DTT concentration in the absence (closed circle) or presence of AtTrx-f2 (open triangle) or PtTrxF (open circle). B, the same experiment as A was performed on mPtCA2. Insets, DTT-dependent activation of mPtCAs in the presence of Trxs at [DTT] of less than 0.5 mm. Values are mean ± S.D. of three duplicates.

TABLE 1.

Half-saturation constant (S0.5) of mPtCA1 and mPtCA2 for DTT, and maximum CA activities at saturated DTT

| S0.5 | WAUmax | |

|---|---|---|

| WAU mg−1protein | ||

| mPtCA1 | ||

| TT | 10.79 ± 5.00 (mm) | 48.6 ± 7.8 |

| DTT (+10 μm AtTrx-f2) | 56.3 (μm) | 71.5 |

| DTT (+10 μm AtTrx-m2) | 49.5 (μm) | 72.7 |

| DTT (+5 μm PtTrxF) | 14.2 (μm) | 72.5 |

| DTT (+5 μm PtTrxM) | 14.01 ± 6.36 (μm) | 69.8 ± 7.2 |

| mPtCA2 | ||

| DTT | 8.58 ± 2.78 (mm) | 47.4 ± 6.5 |

| DTT (+10 μm AtTrx-f2) | 16.9 (μm) | 49.0 |

| DTT (+10 μm AtTrx-m2) | 44.6 (μm) | 44.9 |

| DTT (+5 μm PtTrxF) | 6.5 (μm) | 54.5 |

| DTT (+5 μm PtTrxM) | 14.42 ± 0.34 (μm) | 56.7 ± 2.3 |

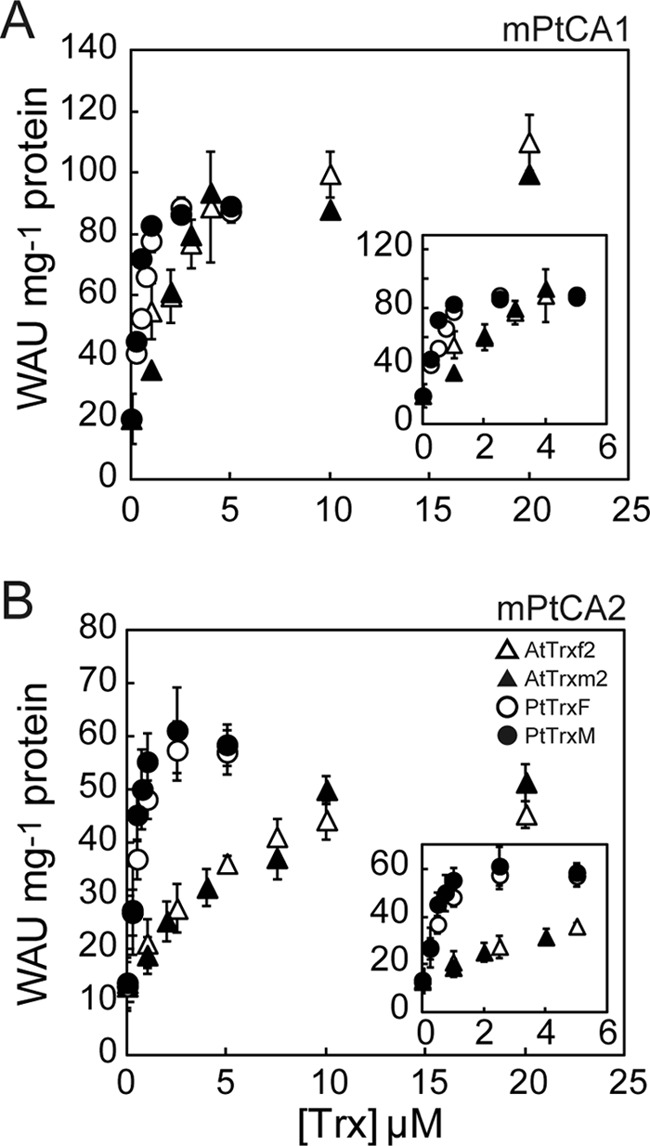

Comparison of Efficiency of Trx-dependent Activation of mPtCAs

The data in Fig. 2 indicate that a concentration of 3 mm DTT is sufficient to reduce PtCAs in the presence of Trx. In the presence of 6 mm DTT, mPtCA1 activity increased steeply with increasing concentrations of AtTrx-f2, with an apparent saturation curve, and reached saturation at about 10 μm AtTrx-f2 (Fig. 3A). The maximum CA activity was also significantly increased compared with DTT treatment alone and reached 126 WAU mg−1 of protein (Fig. 3A and Table 2). The same tendency of the stimulation profile of AtTrx-m2 to that of AtTrx-f2 was observed in the presence of 6 mm DTT (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, stimulation by PtTrxF and PtTrxM showed significantly higher efficiency to mPtCA1 compared with AtTrxs and the activity reached saturation at about 2 μm PtTrxs (Fig. 3A). The maximum CA activity reached 98–117 WAU mg−1 of protein (Fig. 3A and Table 2), about 2.5-fold that with DTT alone (Fig. 2A and Table 1). S0.5[Trx] values were calculated to be 2.1 and 1.98 μm for AtTrx-f2 and -m2, respectively, whereas those for PtTrxF and PtTrxM were 0.34 and 0.44 μm, revealing a 7-fold higher efficiency in transferring the electrochemical potential than that of AtTrxs (Table 2).

FIGURE 3.

Trx-dependent activation of mPtCAs. 5 μm mPtCA1 (A) and mPtCA2 (B) were initially oxidized by 50 μm CuCl2 and then incubated with various concentrations of AtTrx-f2 (open triangle), AtTrx-m2 (closed triangle), PtTrxF (open circle), or PtTrxM (closed circle) in the presence of 6 mm DTT for 1 h at 20 °C. CA activity was plotted as a function of Trx concentrations. Insets, Trx-dependent activation of mPtCAs at [Trxs] of less than 5 μm. Values are mean ± S.D. of three duplicates.

TABLE 2.

Half-saturation constant (S0.5) of mPtCA1 and mPtCA2 for thioredoxins, and maximum CA activities at saturated Trxs in the presence of 6 mm DTT

| S0.5 | WAUmax | |

|---|---|---|

| μm | WAU mg−1protein | |

| PtCA1 | ||

| AtTrx-f2 | 2.10 ± 1.12 | 125.7 ± 34.1 |

| AtTrx-m2 | 1.98 ± 0.44 | 129.7 ± 11.9 |

| PtTrxF | 0.34 ± 0.12 | 97. 7 ± 4.3 |

| PtTrxM | 0.44 ± 0.17 | 117.4 ± 33.6 |

| PtCA2 | ||

| AtTrx-f2 | 1.23 ± 0.25 | 56.3 ± 7.8 |

| AtTrx-m2 | 1.33 ± 0.57 | 49.7 ± 3.6 |

| PtTrxF | 0.32 ± 0.05 | 62.4 ± 1.5 |

| PtTrxM | 0.47 ± 0.15 | 70.4 ± 5.0 |

mPtCA2 activity also increased with the increasing concentration of Trxs, following an apparent rectangular hyperbola function (Fig. 3B). But unlike mPtCA1, there was little increase in the maximum activities with all tested Trxs, and mPtCA2 activity under sufficient concentrations of Trxs and DTT was maintained at 50–70 WAU mg−1 of protein (Fig. 3B and Table 2). In contrast, S0.5[Trx] values of AtTrx-f2, AtTrx-m2, PtTrxF, and PtTrxM with mPtCA2 were equivalent to those observed in mPtCA1, respectively (1.23, 1.33, 0.32, and 0.47 μm, see Table 2). Again, significant differences in stimulation of affinity between Trxs from A. thaliana and those from P. tricornutum were demonstrated and endogenous Trxs were found to possess ∼3.5 times higher activation efficiency for mPtCA2 than that of AtTrxs. These parameters are summarized in Table 2.

Identification of Critical Cysteines for Redox Control of mPtCAs

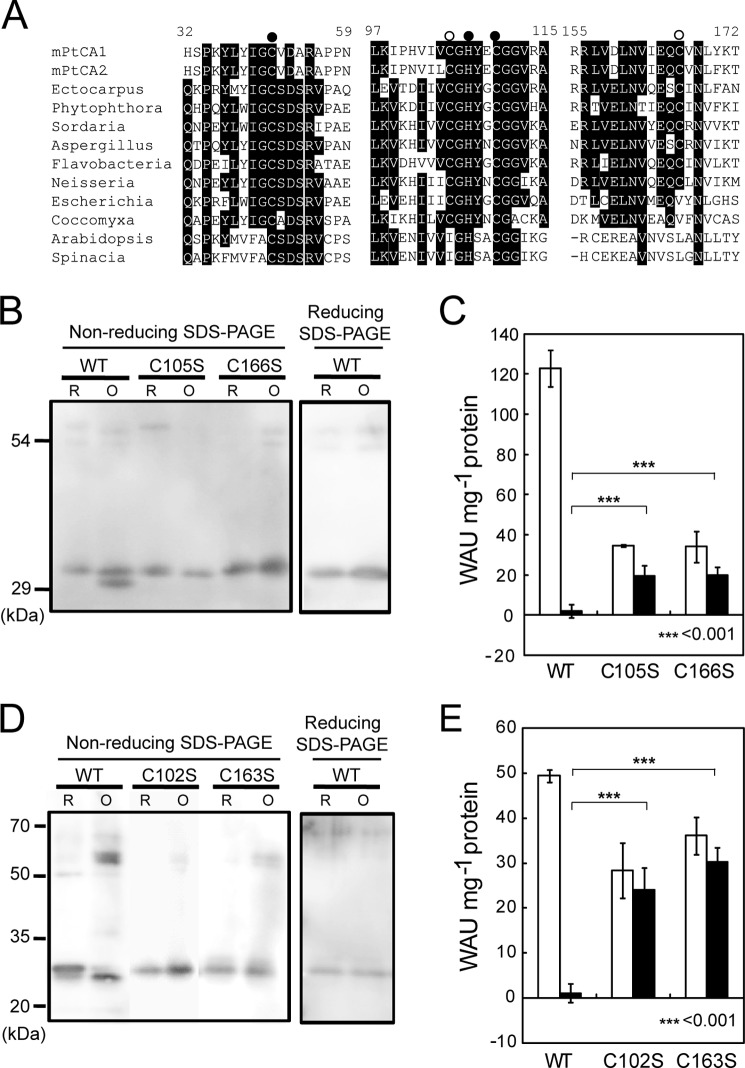

The deduced amino acid sequence of PtCA1 revealed the occurrences of 2 Cys residues at positions 105 and 166, relative to the first N terminus amino acid of mPtCA1 (Fig. 4A, open circles), which probably do not belong to the conserved zinc coordination site (Fig. 4A, closed circles). The analogous allocation of two Cys residues was also observed in mPtCA2, Cys-102 and Cys-163 relative to the putative first N terminus amino acid (Fig. 4A, open circles). Such extra Cys residues besides those in the zinc coordination site are also conserved in β-CAs of some bacteria and fungi but not in higher plants (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Sequence comparison of β-CAs from several origins, molecular weight analysis, and activity of reduced and oxidized forms of wild-type and Cys-substituted mutant of mPtCAs. A, PtCA1 and PtCA2 were compared with β-CAs of several origins. Residues of the putative zinc ligand (closed circle) and the putative disulfide forming cysteine (open circle). B, purified recombinant mPtCA1 (WT) and mutant mPtCA1 (C105S and C166S), after reduction (R) or oxidization (O), were separated by nonreducing or reducing SDS-PAGE. C, activities of the reduced (open bar) and oxidized (closed bar) forms of wild-type and mutant mPtCA1. D and E, the same analysis as A and B was carried out for purified recombinant mPtCA2. Values are mean ± S.D. of three duplicates. Statistical significance was determined by t test (***, p < 0.001).

Alterations of the apparent molecular mass of PtCAs upon oxidation were examined by nonreducing SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis using anti-PtCAs antisera. mPtCA1 after treatment with DTT/Trx appeared as a monomeric band with an apparent molecular mass of about 30 kDa, but upon oxidation by CuCl2, mPtCA migrated significantly faster than the reduced enzyme (Fig. 4B, WT). This alteration of the apparent molecular mass by the redox state of mPtCA1 was not detected in reducing SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4, B and D). To confirm the critical cysteine residues that are targeted by Trxs, we introduced Cys/Ser substitutions to the sites encoding Cys-105 and -166 in mptca1. Gel-migration assays and the measurement of CA activity on the mutated mPtCA1 proteins, mPtCA1(C105S) and mPtCA1(C166S), clearly showed that neither of these mutant proteins revealed a shift in apparent molecular mass upon oxidization (Fig. 4B, C105S and C166S). In close agreement with these results, regulations in the activity of these mutated CAs became largely insensitive to oxidative inactivation by CuCl2 (Fig. 4C). These mutated mPtCA1(C105S and C166S), held in a reduced state by DTT and Trx, showed intermediate activities equivalent to that in wild-type mPtCA1 reduced by DTT alone (about 40 WAU mg−1 of protein) and this level did not decrease significantly by oxidation (Fig. 4C, C105S and C166S), showing a loss of the synergistic stimulation effect caused by Trx and DTT. The same tendency was also observed in alteration of the apparent molecular weight and CA activity in the mPtCA2 wild-type protein and mutants (C102S and C163S) (Fig. 4, D and E). However, the levels of activity in mutants of mPtCA2 were 30–40 WAU mg−1 of protein, which were equivalent to that of wild-type mPtCA2 in a fully reduced state (Fig. 4E). Interestingly, maximum levels of fully reduced mPtCA1(C105S and C166S) were decreased by mutations to the level equivalent to those in mPtCA2 (Fig. 4C).

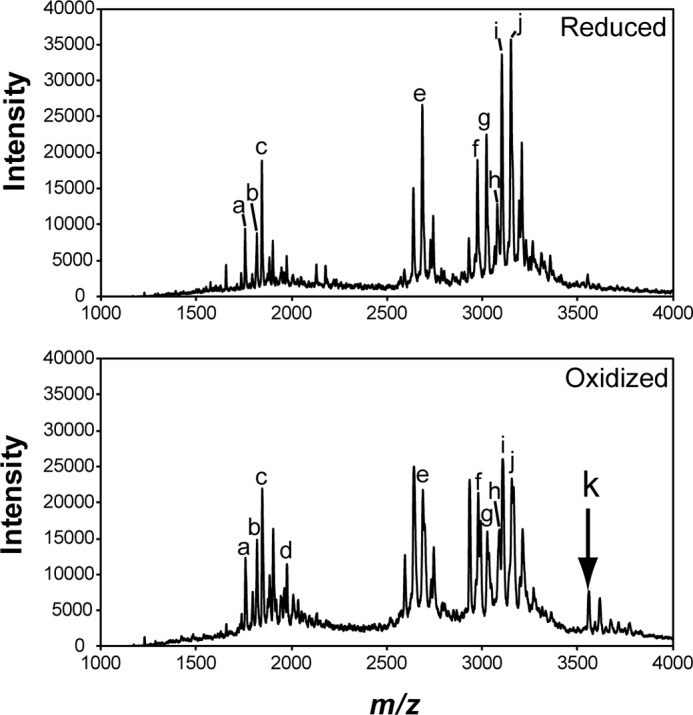

MS Assignment of Modified Cys Residues in mPtCA1

Trypsin-digested fragments of either the reduced or oxidized forms of mPtCA1 were analyzed by mass spectrometry. In the peptide fragments from oxidized PtCA1, one specific signal, which corresponds to the peptides bridged by disulfide between Cys-105 and Cys-166 was repeatedly detected at the spectrum of m/z 3558.5, whereas there was no such peak in the fragments from reduced/alkylated mPtCA1 (Fig. 5). The detailed assignment of peaks detected by mass spectrometry is listed in supplemental Table S1.

FIGURE 5.

MALDI-TOF MS analysis of PtCA1. PtCA1 reduced by DTT (upper diagram) and PtCA1 oxidized by 100% O2 (lower diagram) were alkylated by iodoacetamide and digested by trypsin. The mass spectra of the digested peptide fragments were recorded by MALDI-TOF MS. An arrow indicates the signal corresponding to the disulfide forming fragment of amino acid numbers (100–115) + (158–172). The signals recorded in each spectrum (a–k) were assigned to the corresponding peptide, which is listed in supplemental Table S1. The experiment was repeated three times and a typical data set is shown.

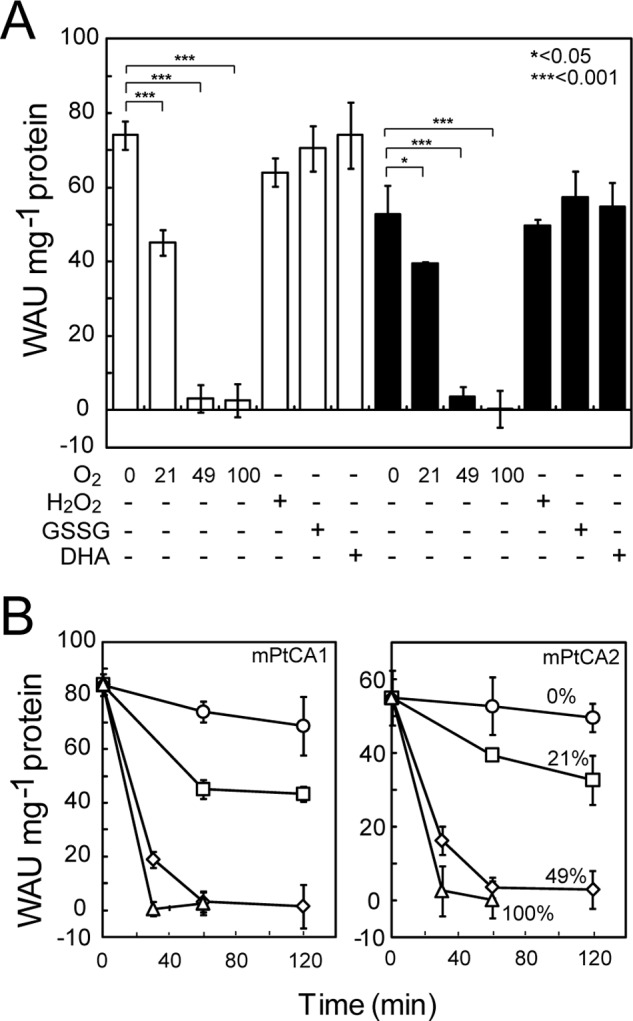

Oxidation of mPtCAs by Candidates of Chloroplastic Oxidants

To investigate putative oxidation factors that may be involved in inactivation of PtCAs in the pyrenoid, oxidation of mPtCA1 was examined by various possible chloroplastic oxidants. Fully reduced mPtCA1 and mPtCA2 showed activity of about 80 and 55 WAU mg−1 of protein, respectively, and these levels were not altered by treatment with gaseous nitrogen (Fig. 6A, 0% O2). However, aeration with atmospheric concentrations of O2 (21%) resulted in partial inactivation to about 60–75% of the maximum activity, and 49 or 100% O2 fully inactivated mPtCAs within 1 h (Fig. 6A). Treatments with 100 μm H2O2 resulted in weak inactivation of mPtCA1, whereas 2 mm GSSG and 500 μm dehydroascorbate showed little inactivation effect to mPtCA1 (Fig. 6A, white bars). These three treatments did not cause inactivation of mPtCA2 (Fig. 6A, black bars). Higher concentrations of these oxidants did not inactivate either mPtCA1 or mPtCA2 (supplemental Fig. S5A). The time course oxidative inactivations of both mPtCA1 and -2 in the presence of PtTrxF were monitored with different concentrations of oxygen, 21, 49, and 100%. In atmospheric levels of O2 (21%), the initial drop of activity was evident for the first 60 min but mPtCAs were not fully inactivated by 21% O2 over 2 h of treatment (Fig. 6B). On the other hand, CA activities decreased significantly to 25–30% of the original activity within the initial 30 min, and were fully inactivated within 1 h in the presence of 49% O2 (Fig. 6B). Pure O2 almost completely inactivated both PtCAs within 30 min (Fig. 6B). These inactivation profiles were also very similar in the absence of PtTrxF with 21 and 49% O2 (supplemental Fig. S5B).

FIGURE 6.

Effect of various chloroplastic oxidants on the activity of mPtCAs. A, fully reduced mPtCA1 and mPtCA2 were treated with 0% O2, 21% O2, 49% O2, 100% O2, 100 μm H2O2, 2 mm GSSG, or 500 μm dehydroascorbate (DHA) prior to measurement of CA activity. Open and closed bars, respectively, indicate results for mPtCA1 and mPtCA2. Values are mean ± S.D. of three duplicates. Statistical significance was determined by t test (*, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001). B, fully reduced mPtCA1 and mPtCA2 were aerated by nitrogen (circle), 21% O2 (square), 49% O2 (diamond), and 100% O2 (triangle) for 30, 60, and 120 min prior to measurement of CA activity. Values are mean ± S.D. of three duplicates.

DISCUSSION

Green algae and higher plants possess a large number of different types of Trxs as well as several isoenzyme copies. In diatoms like P. tricornutum and T. pseudonana most of the thioredoxin types have been identified (Trx m, Trx f, Trx y, Trx o, Trx h), however, the number of isoenzymes is considerably reduced, suggesting that redundant duplication of Trx genes in the green lineage occurred after separation of the red and green lineages (16) (supplemental Fig. S6). This may further account for the possible specialization of Trx function in diatoms, particularly in the case of light-dependent regulation in the plastid. Here some enzymes known to be involved in the Calvin cycle and the pentose phosphate pathway in green algae and land plants, like phosphoribulokinase and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, are not redox regulated (17, 47). Furthermore, Rubisco activase and sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase, targets of Trxs in higher plants, are not present in the diatom plastid (48). It has therefore been proposed that the role of Trxs in controlling the Calvin cycle and the related carbon metabolism in diatoms may be very limited. However, the regulatory mechanisms of many chloroplast processes besides the Calvin cycle remain to be characterized in diatoms, and the role of plastid Trxs in diatoms is as yet unknown. In the present study, a cell-free assay system for the redox regulation of recombinant mPtCA1 and -2 was established, and oxidation by CuCl2 treatment was shown not to affect the capacity of reactivation of mPtCAs. At high concentrations, DTT showed strong efficacy in reactivating the oxidized mPtCAs. Moreover, it became obvious that Trx and DTT synergistically activate PtCAs. These results clearly indicate that the Trxs tested in the present study mediate the transfer of the electrochemical potential of DTT to PtCAs.

The source of this reducing potential in vivo may be ferredoxin in the pyrenoid where both PtCA1 and -2 are localized (35). The concentration of ferredoxin in the illuminated chloroplasts of higher plants is estimated to be 28–750 μm. In the in vitro system described here, several μm DTT were required to fully activate mPtCAs in the presence of Trxs, which is much lower than estimated for potential reductants in higher plant chloroplasts. This suggests that Trx targets, including PtCAs in diatom plastids, may be readily reduced in the light. Other more common chloroplastic reductants may also be involved in PtCA activation. The genome of P. tricornutum contains at least two glutaredoxins that are predicted to be localized in the chloroplast. However, unlike stromal β-CA in Arabidopsis, which has been shown to be activated by glutaredoxin (13), it is not obvious so far whether or not regulatory cysteines of PtCAs possess appropriate redox potentials to accept the electrochemical potential through the glutathione/glutaredoxin system.

Interestingly, Trx mediated the efficient reduction and also stimulated the maximum capacity of PtCA1, but little stimulation of the maximum capacity of PtCA2 by Trx was observed (Fig. 2). These properties were not significantly different when different Trx types were employed. It is thus probable that chloroplast Trxs in general stimulate maximum capacity and/or reduction efficiency in PtCAs. Differences in the mode of redox control between PtCA1 and -2 also suggests different roles for PtCA1 and -2 during possible changes in redox conditions in the pyrenoid of marine diatoms.

Plots of CA activities against concentrations of each Trx under 6 mm DTT (Fig. 3) clearly showed that there is no significant difference in activation capacity of PtCA1 among Trxs tested in this study; in all cases, maximum PtCA1 activity reached about 100–125 WAU mg−1 of the purified mPtCA1 protein (Table 2). In contrast, half-saturation concentrations of DTT and Trxs vary depending on the origin of Trxs. It is noteworthy that a clear species-dependent preference of Trx in activation of mPtCA1 and -2 was observed (Tables 1 and 2). However, the structural details of this observation are yet to be elucidated.

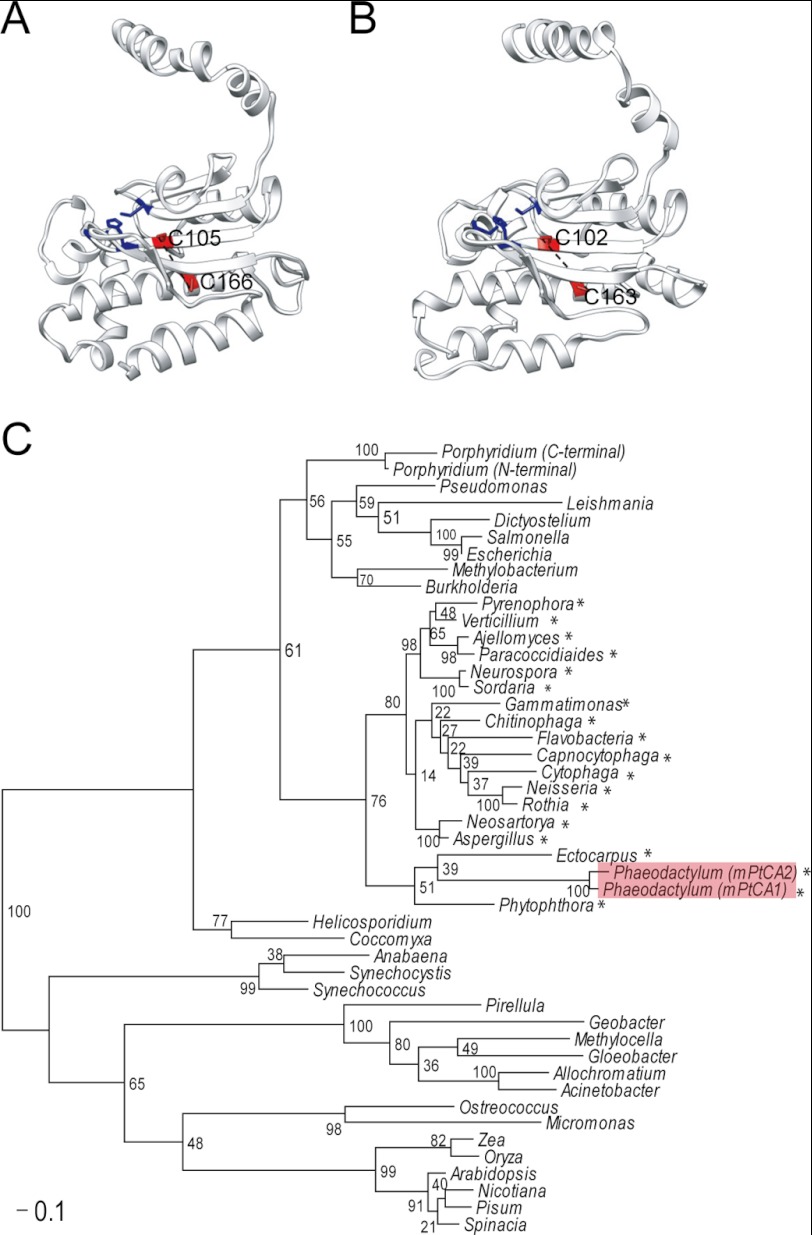

A set of Cys residues responsible for redox control of conformation and activity of PtCAs were successfully characterized in this study (Cys-105 and -166 for PtCA1, and Cys-102 and -163 for PtCA2). The site-directed mutagenesis of these two Cys unequivocally demonstrated that these Cys residues are critical for both oxidized conformation and inactivation of PtCAs (Fig. 4, B–E). Gel-migration assays and mass spectrometry demonstrated the formation of a disulfide bond between two Cys residues in mPtCAs. Predicted models of molecular structures of PtCA1 and -2 indicated that disulfide-forming Cys-105 and -166 in PtCA1, and Cys-102 and -163 in PtCA2 are proximally located at a distance of around 10 Å (Fig. 7, A and B). Although this distance seems to be too great for formation of a disulfide bond, it is probable that the actual distance is closer than that in the predicted model. Alternatively, it is also possible that the tertiary structure surrounding these Cys residues may be flexible and may be perturbed to form a disulfide bond. One of the disulfide bond-forming Cys residues in PtCAs is located in the middle of the zinc coordination site of the CA active center and the other in the fourth helix directly below the active center (Fig. 7, A and B). The formation of disulfide bonds between these two Cys residues by oxidation (Fig. 4) most probably causes a significant constriction of a part of the active center of PtCAs, which may in turn result in a loss of CA activity.

FIGURE 7.

Predicted conformation of activity-modulating disulfide and its phylogenetic distribution among β-CAs. Tertiary structures of mPtCA1 (A) and mPtCA2 (B) were predicted based on the crystallographic structure of β-CA of E. coli. Disulfide-forming Cys residues are shown in red. Zinc chelating sites are show in dark blue. C, phylogenetic tree of 30 β-CA sequences belonging to the clade close to PtCAs. Bootstrap percentages are shown at the nodes of the respective branches. GenBank accession numbers are given after the species names. Asterisks indicate the occurrence of Cys residues homologous to activity modulating Cys pairs in PtCAs.

Interestingly, the atmospheric concentration of molecular oxygen was not sufficient to inactivate mPtCA1 (Fig. 6), whereas a partial pressure of 49% O2 inactivated the enzyme. This result indicates that concentrations slightly above the atmospheric levels are needed to control the activity of PtCAs. Inactivation of PtCAs by O2 occurred in the same way in both the presence and absence of Trx (supplemental Fig. S5). This indicates that PtCA1 and PtCA2 are directly oxidized by molecular oxygen rather than oxidized Trx. Our assumptions to date are that Trxs in the chloroplast of P. tricornutum control the activity of PtCAs in the pyrenoid by balancing the supply of light reducing power and molecular oxygen evolved from the thylakoid lumen in the light. Oxygen and reduced Trxs might be competing in the light for activation/inactivation of PtCAs, strongly suggesting the possible role of this competition as a fine tuning mechanism of CO2 supply, depending on light intensity.

PtCA1 mutants, both C105S and C166S, lost both oxidative inactivation and synergistic activation by Trx and DTT (Fig. 4C). In contrast, as PtCA2 did not show any synergistic activation, the mutation of Cys residues to Ser merely resulted in the absence of inactivation (Fig. 4E). PtCA1 and -2 are paralogous proteins with 76% amino acid similarity. It is thus likely that the key of the synergy effect of activation by DTT and Trx in PtCA1 ascribe to this small percentage (24%) of amino acid sequence that is unique to PtCA1. Molecular mechanisms that result in functional differentiation between PtCAs await further study.

Phylogenetic analysis of β-CAs shows that PtCAs and enzymes from brown algae and oomycetes form a clade distant from land plant β-CAs (Fig. 7C). Chloroplast β-CAs in land plants are regulated by Trxs (12). These β-CAs apparently use different Cys residues for regulation compared with PtCAs (Fig. 4A), strongly suggesting that the mechanism of redox regulation of PtCAs is different from that of land plants. In fact, Cys-267 and Cys-272 in pea chloroplast β-CA are known to be critical for structural integrity at the tetramer-tetramer interface, and for normal catalytic activity (49). β-CAs can be phylogenetically divided into two subgroups: β-CAs in chromists, opisthokonts, and bacteria, and a mixture of enzymes from proteobacteria and higher plants (Fig. 7C). Interestingly, the major difference in these two subgroups is the occurrence of conserved disulfide-forming Cys residues, which are homologous to those in PtCAs (Fig. 7C, asterisks).

The occurrence of these Cys residues appears unlikely to be related to photosynthesis, because in both subgroups of photosynthetic algae, plants as well as heterotrophic bacteria can be found (Fig. 7C), indicative of lateral gene transfers. β-CAs in the photoautotrophs (chlorophyta and rhodophyta) do not possess a set of homologous Cys residues, and, in fact, the activity of Coccomyxa β-CA is known to be independent of redox regulation (50). It is thus unclear what the evolutionary driving force for selecting this particular redox moiety of β-CAs is in the former subgroup.

In the present study, we have demonstrated initial evidence for reductive activation of the pyrenoidal CAs by Trx in microalga. This is also the first direct evidence for a target of plastid Trxs in diatoms, strongly suggesting that the CO2 acquisition system, and not the fixation system, is the target of redox control via Trxs in the diatom plastid. The biochemical architecture and function of the pyrenoid has not been characterized in any pyrenoid-forming chloroplasts. Pyrenoids are believed to be a central part of the CCM, and this study strongly suggests that in the marine diatom P. tricornutum the function of the pyrenoid might be under control of the light-driven reduction mediated by Trx and photosystem-generated oxygen.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nobuko Higashiuchi for technical assistance and Miyabi Inoue for skillful secretarial assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan to Kwansei Gakuin University, Research Center for Environmental Bioscience, and by the Steel Industry Foundation for the Advancement of Environmental Protection Technology (to Y. M.).

This article contains supplemental Table S1 and Figs. S1–S6.

- Trx

- thioredoxin

- Fd

- ferredoxin

- CA

- carbonic anhydrase

- CCM

- CO2-concentrating mechanism

- Rubisco

- ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase

- WAU

- Wilbur-Anderson unit

- PtCA

- P. tricornutum CA.

REFERENCES

- 1. Meyer Y., Buchanan B. B., Vignols F., Reichheld J. P. (2009) Thioredoxins and glutaredoxins. Unifying elements in redox biology. Annu. Rev. Genet. 43, 335–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Buchanan B. B., Balmer Y. (2005) Redox regulation. A broadening horizon. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 56, 187–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schürmann P., Buchanan B. B. (2008) The ferredoxin/thioredoxin system of oxygenic photosynthesis. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 10, 1235–1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meyer Y., Vignols F., Reichheld J. P. (2002) Classification of plant thioredoxins by sequence similarity and intron position. Methods Enzymol. 347, 394–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Arsova B., Hoja U., Wimmelbacher M., Greiner E., Ustün S., Melzer M., Petersen K., Lein W., Börnke F. (2010) Plastidial thioredoxin Z interacts with two fructokinase-like proteins in a thiol-dependent manner. Evidence for an essential role in chloroplast development in Arabidopsis and Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant Cell 22, 1498–1515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lemaire S. D., Miginiac-Maslow M. (2004) The thioredoxin superfamily in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Photosynth. Res. 82, 203–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Collin V., Lamkemeyer P., Miginiac-Maslow M., Hirasawa M., Knaff D. B., Dietz K. J., Issakidis-Bourguet E. (2004) Characterization of plastidial thioredoxins from Arabidopsis belonging to the new y-type. Plant Physiol. 136, 4088–4095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gelhaye E., Rouhier N., Navrot N., Jacquot J. P. (2005) The plant thioredoxin system. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 62, 24–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Motohashi K., Kondoh A., Stumpp M. T., Hisabori T. (2001) Comprehensive survey of proteins targeted by chloroplast thioredoxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 11224–11229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Balmer Y., Koller A., del Val G., Manieri W., Schürmann P., Buchanan B. B. (2003) Proteomics gives insight into the regulatory function of chloroplast thioredoxins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 370–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lemaire S. D., Guillon B., Le Maréchal P., Keryer E., Miginiac-Maslow M., Decottignies P. (2004) New thioredoxin targets in the unicellular photosynthetic eukaryote Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 7475–7480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Johansson I. M., Forsman C. (1993) Kinetic studies of pea carbonic anhydrase. Eur. J. Biochem. 218, 439–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rouhier N., Villarejo A., Srivastava M., Gelhaye E., Keech O., Droux M., Finkemeier I., Samuelsson G., Dietz K. J., Jacquot J. P., Wingsle G. (2005) Identification of plant glutaredoxin targets. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 7, 919–929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Balmer Y., Koller A., Val G. D., Schürmann P., Buchanan B. B. (2004) Proteomics uncovers proteins interacting electrostatically with thioredoxin in chloroplasts. Photosynth. Res. 79, 275–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marchand C., Le Maréchal P., Meyer Y., Miginiac-Maslow M., Issakidis-Bourguet E., Decottignies P. (2004) New targets of Arabidopsis thioredoxins revealed by proteomic analysis. Proteomics 4, 2696–2706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weber T., Gruber A., Kroth P. G. (2009) The presence and localization of thioredoxins in diatoms, unicellular algae of secondary endosymbiotic origin. Mol. Plant 2, 468–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Michels A. K., Wedel N., Kroth P. G. (2005) Diatom plastids possess a phosphoribulokinase with an altered regulation and no oxidative pentose phosphate pathway. Plant Physiol. 137, 911–920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bosco M. B., Aleanzi M. C., Iglesias A. Á. (2012) Plastidic phosphoglycerate kinase from Phaeodactylum tricornutum. On the critical role of cysteine residues for the enzyme function. Protist 163, 188–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Falkowski P. G. (1997) Evolution of the nitrogen cycle and its influence on the biological sequestration of CO2 in the ocean. Nature 387, 272–275 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Field C. B., Behrenfeld M. J., Randerson J. T., Falkowski P. (1998) Primary production of the biosphere. Integrating terrestrial and oceanic components Science 281, 237–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Colman B., Rotatore C. (1995) Photosynthetic inorganic carbon uptake and accumulation in two marine diatoms. Plant Cell Environ. 18, 919–924 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Johnston A. M., Raven J. A. (1996) Inorganic carbon accumulation by the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Eur. J. Phycol. 31, 285–290 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Matsuda Y., Hara T., Colman B. (2001) Regulation of the induction of bicarbonate uptake by dissolved CO2 in the marine diatom, Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Plant Cell Environ. 24, 611–620 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Trimborn S., Wolf-Gladrow D., Richter K. U., Rost B. (2009) The effect of pCO2 on carbon acquisition and intracellular assimilation in four marine diatoms. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 376, 26–36 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reinfelder J. R., Milligan A. J., Morel F. M. (2004) The role of the C4 pathway in carbon accumulation and fixation in a marine diatom. Plant Physiol. 135, 2106–2111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harada H., Nakajima K., Sakaue K., Matsuda Y. (2006) CO2 sensing at ocean surface mediated by cAMP in a marine diatom. Plant Physiol. 142, 1318–1328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Harada H., Nakatsuma D., Ishida M., Matsuda Y. (2005) Regulation of the expression of intracellular β-carbonic anhydrase in response to CO2 and light in the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Plant Physiol. 139, 1041–1050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fukuzawa H., Suzuki E., Komukai Y., Miyachi S. (1992) A gene homologous to chloroplast carbonic anhydrase (icfA) is essential to photosynthetic carbon dioxide fixation by Synechococcus PCC7942. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 4437–4441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Price G. D., Badger M. R. (1989) Expression of human carbonic anhydrase in the Cyanobacterium synechococcus PCC7942 creates a high CO2-requiring phenotype. Evidence for a central role for carboxysomes in the CO2 concentrating mechanism. Plant Physiol. 91, 505–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Funke R. P., Kovar J. L., Weeks D. P. (1997) Intracellular carbonic anhydrase is essential to photosynthesis in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii at atmospheric levels of CO2. Demonstration via genomic complementation of the high CO2-requiring mutant ca-1. Plant Physiol. 114, 237–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Raven J. A. (1997) CO2-concentrating mechanisms. A direct role for thylakoid lumen acidification? Plant Cell Environ. 20, 147–154 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Van K., Spalding M. H. (1999) Periplasmic carbonic anhydrase structural gene (Cah1) mutant in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol. 120, 757–764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Armbrust E. V., Berges J. A., Bowler C., Green B. R., Martinez D., Putnam N. H., Zhou S., Allen A. E., Apt K. E., Bechner M., Brzezinski M. A., Chaal B. K., Chiovitti A., Davis A. K., Demarest M. S., Detter J. C., Glavina T., Goodstein D., Hadi M. Z., Hellsten U., Hildebrand M., Jenkins B. D., Jurka J., Kapitonov V. V., Kröger N., Lau W. W., Lane T. W., Larimer F. W., Lippmeier J. C., Lucas S., Medina M., Montsant A., Obornik M., Parker M. S., Palenik B., Pazour G. J., Richardson P. M., Rynearson T. A., Saito M. A., Schwartz D. C., Thamatrakoln K., Valentin K., Vardi A., Wilkerson F. P., Rokhsar D. S. (2004) The genome of the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana. Ecology, evolution, and metabolism. Science 306, 79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bowler C., Allen A. E., Badger J. H., Grimwood J., Jabbari K., Kuo A., Maheswari U., Martens C., Maumus F., Otillar R. P., Rayko E., Salamov A., Vandepoele K., Beszteri B., Gruber A., Heijde M., Katinka M., Mock T., Valentin K., Verret F., Berges J. A., Brownlee C., Cadoret J. P., Chiovitti A., Choi C. J., Coesel S., De Martino A., Detter J. C., Durkin C., Falciatore A., Fournet J., Haruta M., Huysman M. J., Jenkins B. D., Jiroutova K., Jorgensen R. E., Joubert Y., Kaplan A., Kröger N., Kroth P. G., La Roche J., Lindquist E., Lommer M., Martin-Jézéquel V., Lopez P. J., Lucas S., Mangogna M., McGinnis K., Medlin L. K., Montsant A., Oudot-Le Secq M. P., Napoli C., Obornik M., Parker M. S., Petit J. L., Porcel B. M., Poulsen N., Robison M., Rychlewski L., Rynearson T. A., Schmutz J., Shapiro H., Siaut M., Stanley M., Sussman M. R., Taylor A. R., Vardi A., von Dassow P., Vyverman W., Willis A., Wyrwicz L. S., Rokhsar D. S., Weissenbach J., Armbrust E. V., Green B. R., Van de Peer Y., Grigoriev I. V. (2008) The Phaeodactylum genome reveals the evolutionary history of diatom genomes. Nature 456, 239–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tachibana M., Allen A. E., Kikutani S., Endo Y., Bowler C., Matsuda Y. (2011) Localization of putative carbonic anhydrases in two marine diatoms, Phaeodactylum tricornutum and Thalassiosira pseudonana. Photosynth. Res. 109, 205–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Harada H., Matsuda Y. (2005) Identification and characterization of a new carbonic anhydrase in the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Can. J. Bot. 83, 909–916 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Satoh D., Hiraoka Y., Colman B., Matsuda Y. (2001) Physiological and molecular biological characterization of intracellular carbonic anhydrase from the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Plant Physiol. 126, 1459–1470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Xu Y., Feng L., Jeffrey P. D., Shi Y., Morel F. M. (2008) Structure and metal exchange in the cadmium carbonic anhydrase of marine diatoms. Nature 452, 56–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cox E. H., McLendon G. L., Morel F. M., Lane T. W., Prince R. C., Pickering I. J., George G. N. (2000) The active site structure of Thalassiosira weissflogii carbonic anhydrase 1. Biochemistry 39, 12128–12130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tanaka Y., Nakatsuma D., Harada H., Ishida M., Matsuda Y. (2005) Localization of soluble β-carbonic anhydrase in the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Sorting to the chloroplast and cluster formation on the girdle lamellae. Plant Physiol. 138, 207–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stumpp M. T., Motohashi K., Hisabori T. (1999) Chloroplast thioredoxin mutants without active-site cysteines facilitate the reduction of the regulatory disulfide bridge on the γ-subunit of chloroplast ATP synthase. Biochem. J. 341, 157–163 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wilbur K. M., Anderson N. G. (1948) Electrometric and colorimetric determination of carbonic anhydrase. J. Biol. Chem. 176, 147–154 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Laemmli U. K. (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Larkin M. A., Blackshields G., Brown N. P., Chenna R., McGettigan P. A., McWilliam H., Valentin F., Wallace I. M., Wilm A., Lopez R., Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Higgins D. G. (2007) Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Vallat B. K., Pillardy J., Elber R. (2008) A template-finding algorithm and a comprehensive benchmark for homology modeling of proteins. Proteins 72, 910–928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Guindon S., Dufayard J. F., Lefort V., Anisimova M., Hordijk W., Gascuel O. (2010) New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 59, 307–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Liaud M. F., Lichtlé C., Apt K., Martin W., Cerff R. (2000) Compartment-specific isoforms of TPI and GAPDH are imported into diatom mitochondria as a fusion protein. Evidence in favor of a mitochondrial origin of the eukaryotic glycolytic pathway. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17, 213–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kroth P. G., Chiovitti A., Gruber A., Martin-Jezequel V., Mock T., Parker M. S., Stanley M. S., Kaplan A., Caron L., Weber T., Maheswari U., Armbrust E. V., Bowler C. (2008) A model for carbohydrate metabolism in the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum deduced from comparative whole genome analysis. PLoS One 3, e1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Björkbacka H., Johansson I. M., Skärfstad E., Forsman C. (1997) The sulfhydryl groups of Cys-269 and Cys-272 are critical for the oligomeric state of chloroplast carbonic anhydrase from Pisum sativum. Biochemistry 36, 4287–4294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hiltonen T., Björkbacka H., Forsman C., Clarke A. K., Samuelsson G. (1998) Intracellular β-carbonic anhydrase of the unicellular green alga Coccomyxa. Cloning of the cdna and characterization of the functional enzyme overexpressed in Escherichia coli. Plant Physiol. 117, 1341–1349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]