Abstract

Previous research in India indicates that there is little communication within marriage about sex. Lack of communication about safe sexual behaviours may increase couples’ vulnerability to HIV. This study explores couple level sexual communication and socio-cultural norms that influence couples’ communication about sex and its implications for HIV prevention. Data derive from in-depth interviews at two points in time with 10 couples. Secondary qualitative analyses of the interviews were conducted using inductive and deductive coding techniques. Half of the couples described improved communication about sex and HIV and AIDS after participation in the clinical trial and/or acceptability study, as well as increased sexual activity, improved relationships by alleviating doubts about their partner’s fidelity and forgiving their partners. The findings show that creating safe spaces for couples where they can ask frank questions about HIV and AIDS, sex and sexuality potentially can improve couples’ communication about sex and reduce their risk for HIV infection.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, India, couples, sexual communication, microbicide

Introduction

Marriage is an important risk factor for HIV for women worldwide (Hirsch et al. 2007; Phinney 2008; Smith 2007; Wardlow 2007). There are 2.47 million Indian adults (aged 15 and older) living with HIV, 39% of whom are women (National AIDS Control Organization 2008). Most Indian women are infected with HIV by husbands who engage in sexual relationships outside of marriage (Gangakhedkar et al. 1997; Ghosh, Wadhwa, and Kalipeni 2009; SriKrishnan et al. 2007). Mutual monogamy of married partners is not guaranteed and social and gender norms about sex and faithfulness are unequally applied, usually to the detriment of women (Daniel, Masilamani, and Rahman 2008; George 1998; George and Jaswal 1995). Condom use, a potentially protective factor from HIV for married women, is low within marriage due to socio-cultural norms that it implies infidelity or lack of trust (Severy et al. 2005; Tolley et al. 2006). Additionally, the desire to bear children, particularly for younger married couples, makes condom use or abstinence from sexual activity unattractive (Daniel, Masilamani, and Rahman 2008).

HIV, AIDS and sexual communication

Communication about sex between heterosexual partners consistently predicts safer sexual behaviours, including those that reduce risk of HIV infection, such as HIV and STI testing and condom use (Bandura 1990; Becker 1996; Maharaj and Cleland 2005; Montgomery et al. 2008). Several studies in the USA demonstrate that discussion of safer sex with a partner is associated with safer sexual practices (Catania et al. 1994; Edgar et al. 1992; Freimuth et al. 1992). A meta-analysis showed that discussion of condom use was the strongest correlate with actual condom use compared to other psychosocial predictors (Sheeran, Abraham, and Orbell 1999). Other studies showed that the nature of the communication was important, with discussions about sexual history predicting condom use (Rickman et al. 1994) and about HIV and AIDS also predicting condom use (DiClemente 1991). Another study found that individuals who are trained in sexual communication skills are also more likely to enact safer sexual behaviours (Kalichman, Rompa, and Coley 1996). These findings elucidate the importance of sexual communication as a critical component of HIV-risk reduction for heterosexual couples.

Whether heterosexual couples communicate about sex, and subsequently enact behaviours that reduce their risk for HIV, is influenced not only by individual level attributes of each member of the dyad, but also by environmental and socio-cultural contexts in which the dyad lives. These contexts may inhibit or facilitate discussions about sex, HIV risk, condom use, HIV testing and other reproductive health issues. For example, maintaining a relationship with a partner may supersede concerns over risk of HIV infection, particularly in contexts where women are dependent on men for basic necessities for themselves and their children. Women may be loath to discuss their previous sexual relationships for fear of losing their current partner (Cline, Johnson, and Freeman 1992; Perlmutter and Michal-Johnson 1989). Even if women are motivated to discuss sex with their partners and negotiate condom use, they are not always able to enact these behaviours due to power differentials in the relationship (Carovano 1991; Garcia-Moreno and Rodrigues 1992). Where men have power over women, sex may not be a choice for women but, rather, an obligation. The discussion of sex in and of itself is highly stigmatised in some contexts and is considered a taboo topic, particularly for unmarried women. Women in some settings are considered promiscuous or unfaithful for simply raising the issue. HIV and AIDS are also highly stigmatised in many settings and discussions about it among married couples incite suspicions of infidelity (Hirsch et al. 2007; Phinney 2008; Smith 2007; Wardlow 2007).

Previous research of married couples in India demonstrates that there is very little communication within marriage about sexual and reproductive health (George 1998; Lambert and Wood 2005; Sivaram et al. 2005). A study in the slums of Chennai with married men and women showed that married men discussed sex with close friends but rarely with their wives and that married women were unlikely to discuss sex with their husbands and often acquiesced to their husbands’ demands for sex (Sivaram et al. 2005). Married women did negotiate condom use with their husbands where they perceived a risk (e.g. they thought their husband had other partners). However, another study of wives of STI patients in Pune found that they did not understand the risk of STI/HIV infection from their spouses (Mawar et al. 1997). Perceived risk is a necessary precursor to preventive behaviours, such as condom use, and where women perceive no or little risk for HIV infection from their husbands, they are unlikely to discuss sex and use condoms (Gerrard, Gibbons, and Bushman 1996). This lack of understanding of risk and absence of communication about safe sexual behaviours may increase couples’ vulnerability to HIVand other sexually transmitted diseases. However, little research focuses specifically on sexual communication related to HIV risk and protective behaviours among married couples.

In this paper we examine how married couples communicate about sex within the context of a microbicide clinical trial and concurrently conducted acceptability study. Through secondary analysis of in-depth interviews we describe couple-level sexual communication patterns and identify socio-cultural norms that influence couples’ communication about sex. We further examine whether or how participation in a clinical trial and/or acceptability study affected couples’ sexual communication patterns.

Methods

Sample

The data for this analysis derive from repeated, in-depth interviews with a subset of couples participating in a prospective study to examine the acceptability and sustained use of vaginal microbicides in Pune, India. The prospective acceptability study was conducted in parallel to a multi-site, randomised, controlled trial (HIV Prevention Trials Network/HPTN 059) to assess the extended safety and acceptability of Tenofovir 1% gel as an HIV prevention product (Tolley 2006). The objectives and study requirements of the clinical trial have been described elsewhere (Tolley 2006). Pune was selected as the study site because the National AIDS Research Institute (NARI) of India is located there and the institute is equipped to conduct clinical trials and socio-behavioural research. Pune, located in the state of Maharashtra, has a much higher HIV prevalence (2.9%) compared to all of India (0.3%) and is therefore an important site for HIV and AIDS research (National AIDS Control Organization 2008).

The acceptability study identified psychosocial predictors of sustained microbicide use in Pune. Two cohorts of women were enrolled: 100 participants of the HPTN 059 trial and 100 women drawn from the same communities who were unable or unwilling to participate in the clinical trial. In addition, 109 partners (53 husbands of clinical trial participants and 56 of non-trial participants) were enrolled. Acceptability study participants took part in structured interviews at baseline, 2, 4 and 6 months. To understand more in-depth topics related to microbicide acceptability and experiences participating in the clinical trial, women enrolled in the studies were approached by acceptability study staff to also participate in in-depth interviews and were recruited until reaching 20 women. In addition, 10 husbands of women were recruited to understand the couple dynamics of using microbicides and the experience of participation in the clinical trial. Recruitment of husbands proved not to be difficult in this setting and many husbands appreciated the opportunity to take part in the study. Qualitative interviews were conducted at approximately three and five months after enrolment, five married couples participated in the clinical trial and acceptability study, the other five in the acceptability study only.

In-depth interviews with the 10 married couples were conducted in Marathi or Hindi, with women and men separately, by same gender interviewers using interview guides. Interviewers held master’s degrees in social science and were trained in several multiple day sessions covering the following topics: interviewing techniques and probing, data collection, data analysis and how to discuss sex and sexuality in an interview setting. Interviews explored themes of couple harmony, household decision-making, couple sexual intimacy and communication, microbicide effect on sexual intimacy, STI/HIV risk, condom versus microbicide use, trial participation and microbicide acceptability. Interview guides were pre-tested and questions adjusted for clarity and content. Interviewers were trained in interviewing skills and interviews were periodically reviewed by study principal investigators for quality of data. The interviews were tape recorded, transcribed and translated into English in preparation for analysis. Interviews lasted one to two hours. All participants gave informed consent and Institutional Review Boards of Family Health International and the Indian National AIDS Research Institute approved the study.

Analysis

The unit of analysis for the interviews is the couple. Although men and women were interviewed separately and a total of 40 individual interviews were conducted, interviews were read as couple units. Deductive qualitative analysis focused on couple sexual intimacy and communication (Berg 2004), with attention to different gendered perspectives regarding the salient themes. Interview transcripts were uploaded into the qualitative software package NVivo, Version 8 (QSR International 2008). A codebook was created using deductive themes derived from the interview guide as well as inductive themes emergent from the data (Berg 2004). Codes were created by the first author after reading all transcripts and then discussed and revised with input from the second author. Matrices were created by the first author to compare couples based on theme-related characteristics.

Findings

Demographic characteristics

The average age of female participants in the in-depth interviews was 33.6 years (range 26-44) and for male participants was 39.4 years (range 29-50). In all-but-one of the couples, the husband was older than the wife by four or more years. One woman had completed primary school only, three women had completed 5-9 years of schooling compared to six men, three women had completed 10 years of schooling, whereas no men were in this category, and four men and three women had completed more than 10 years of education. Three couples were in the same education category, in four couples the wife had more education than the husband and in three couples the husband was more educated than the wife. Most couples were Hindu (80%) and 20% were Buddhist. In all ten couples both partners were the same religion. The average number of living children per couple was 2.2 (range-1-4) and the average monthly household income was 6650 Rupees (US $127.61). The range of household income varied greatly, from 3400 Rupees (US $65.24) to 20000 Rupees (US $383.80).

Socio-cultural norms influencing couples’ sexual communication

Couples described direct and indirect patterns to verbally or non-verbally communicate sexual desire. Most often, couples communicated their desire for sex indirectly through touch, gestures and code words. Three of ten couples only communicated non-verbally, with both partners reporting this type of sexual communication. One couple described this:

No, we don’t tell each other. We understand each other’s expressions. We understand the gestures or nature of each other. (couple 69, Anu, wife, age 30)

There is no need to express feelings … because when we sleep together, all these things happen automatically … sometimes she takes initiative or sometimes I take initiative … she does not speak … (couple 69, Ravi, husband, age 28)

Most often, verbal communication about sex was indirect, usually because of the presence of other family members in the household and lack of privacy. It was considered inappropriate to discuss sex in front of family members or children, therefore couples employed different strategies to communicate sexual desire. One husband explained: ‘We can’t talk openly. Only verbal signs. … We have our own code-words’ (couple 67, Sanjay, age 40). Seven of the ten couples shared their bedrooms with their children or extended family members, necessitating non-verbal and indirect communication. Parents feared unduly influencing their children and described waiting to have sex until the children were asleep or sending children to relative’s homes so that the couple could have sex. Six couples used a combination of non-verbal communication or indirect verbal communication, whereas both partners in only one couple reported direct verbal communication about sex. Among all couples, there was agreement about their sexual communication styles.

Gender differences in sexual communication styles were evident in the couples’ interviews. Men and women reported that men could ask women for sex verbally, but women tended to express sexual desire non-verbally. One woman admitted: ‘I never expressed my sexual desire orally till today [in the interview]’ (couple 44, Lakshmi, wife, age 28). For three couples, the husband verbally asked for sex and the wife responded non-verbally:

In privacy he speaks freely about sexual relations. … My husband touches me and says … I won’t be able to tell what he says after that … I can’t. I can’t utter those words from my mouth. (couple 101, Daya, wife, age 42)

… she tells indirectly … she expresses her wish by touch or there is a change in communication … I get hints from that. (couple 101, Manoj, husband, age 50)

Control over sexual timing and the ability to refuse sex emerged as another important dimension of couples’ sexual communication. When one partner expresses a desire to have sex, it appears that a process of negotiation follows. Only one couple described this as a joint decision in which either party could refuse or accept. They explained:

When he desires to have sex, we have sex, and when he is too tired, he can tell me that he does not want to have sex … if I desire to have sex, we have sex, and if I don’t desire, I reject sex. (couple 35, Kavita, wife, age 26)

Desires are very important. I feel if [the] wife is not wishing to [have] sex then [the] husband should not force [it] on her. If [the] husband is not willing then [the] wife should not trouble him. (couple 35, Raj, husband, age 34)

In four of the ten couples, the wife believed that she could not refuse sex. Women felt obligated to have sex with their husbands, even when they didn’t desire sex:

At the time, I say ‘No’, but I have to follow his wishes. (couple 30, Aarti, wife, age 44)

… I try to convince her. … In the evening even if she doesn’t allow me to touch her I force her softly. No one, either a man or a woman, can control sexual desire. (couple 30, Rajesh, husband, age 42)

Not only wives feel obligated to have sex when their husbands desire, but several husbands also feel obliged to have sex if their wife desires. Men described the need to fulfil their wives’ desires and keep them happy:

If she expresses her desire in this way then I must have sex. Though I don’t have desire to have sex, I must be ready … because I have to keep my wife happy. (couple 44, Rajeev, husband, age 35)

Four husbands expected their wives to be sexually available when they desired sex; other husbands believed it was important that both the husband and wife agree to sex. One husband said that: ‘Males should keep sexual relationship[s] according to the response of the ladies’ (couple 69, Ravi, husband, age 28) and another said:

Wish … it is very important. Suppose one of them is not willing [for sex] and [the] other wants it then it’s kind of using [the] other’s body … isn’t it?’ (couple 34, Kavish, husband, age 37)

Husbands took indirect verbal cues or non-verbal gestures from their wives indicating that they did or did not wish to have sex.

When a wife refuses sex, it can lead to further sexual vulnerability; however, men are not held to the same standard. Six women and two men stated that when a woman refuses sex, the husband believes that she is unfaithful. This theme was mentioned by both the husband and wife in only one couple. They explained:

Suppose when the husband goes close to her for sexual relations, she gets irritated and she can’t allow him to come close … then he understands that she keeps outside sexual relations. (couple 44, Rajeev, husband, age 35)

Interviewer: What might lead a man to worry that his wife is not faithful?

Participant: When she refuses [to have sex].

Interviewer: What does he think?

Participant: [The] husband thinks that she must be having [an affair] outside, [because] she is not allowing me to touch her. Many husbands think like this. (couple 44, Lakshmi, wife, age 28)

Most women reported being faithful to their husbands but wanting to refuse sex for other reasons, such as lack of desire; however, they might agree to sex to avoid forced sex or accusations of infidelity. One woman described this:

But let me tell you, I have sexual relations due to fear of quarrelling. If I don’t … he says that I keep outside sexual relations. Otherwise I don’t have [an] interest in keeping sexual relations … (couple 70, Anita, wife, age 36)

Not only were women vulnerable in the context of their marriage, they were also vulnerable in their families and society if they were accused of infidelity. One man described social ostracism or even death as the ultimate punishment for women’s sexual infidelity:

Actually our society is very sensitive about … sexual matters. If any girl keeps outside sexual relations then [she is ostracised] from society. Or father-in-law, mother-in-law, husband, all family members burn [her] or motivate her to suicide. (couple 101, Manoj, husband, age 50)

Men, on the other hand, were not held to the same standard of fidelity within marriage. In fact, suspicion of a wife’s infidelity or inability to satisfy her husband’s sexual needs essentially gave a husband permission to seek sexual relationships outside of marriage. Both men and women endorsed this social norm:

If he does not get a proper sexual response from his wife then he may go for extra-marital affairs. If his sexual desire is not fulfilled by his wife, he may go to some other lady in search of his satisfaction. (couple 35, Raj, husband, age 34)

Means the wife should behave well though her husband does not behave well. Because she is woman and her husband is man. He can do anything. But the woman should be modest. (couple 70, Anita, wife, age 36)

Couples described sexuality as a taboo topic that left many young couples ignorant about sex until they initially experienced it. One wife was fortunate to have a family doctor who explained sex to her before her wedding:

… [she] told [me] everything about sexual contacts. Even though I had completed my college I did not know anything about such things. I heard it for [the] first time. At that time I felt very odd. (couple 69, Anu, wife, age 30)

Other young men and women received no education about sex prior to marriage and were apprehensive as they entered into union. For example, one couple admitted that they had no knowledge about sex until their wedding night:

We both were totally ignorant about sexuality … till our wedding. We had no knowledge about sex. But once you jump into water you learn to swim. (couple 67, Sanjay, husband, age 40)

Half of the male participants expressed that men, in general, could not control their sexual desire and that men always desired sex. One participant explained:

See, we [men] are going to have sexual desire every time. It’s like thirst. We drink water when we are thirsty, same is with sexual desire … same is applicable for sexual hunger. We always desire for sex. (couple 35, Raj, husband, age 34)

Several male participants reported that they personally could not control their sexual desire. The same men said that women can control their sexual desire, that they are better at it, and that they do not face the same dilemmas as men. One man explained:

Males can not control their sexual desire. A female can perhaps control. With males … they don’t get satisfaction till ejaculation. Ladies don’t have to face any such thing. (couple 70, Amar, husband, age 40)

In contrast, no discussion of sexual desire was expressed by women, except when they described their lack of sexual desire and its consequences for their marriage.

Influence of the clinical trial/acceptability study participation on sexual communication

Participation in the microbicide acceptability study and/or clinical trial influenced couples’ sexual communication, even though there was no specific intervention to improve communication. Five couples participating in the clinical trial and/or acceptability study reported improved communication after participation because it allowed them to discuss sexual and reproductive health matters openly, to resolve their doubts about HIV and contraception and to discuss sex with their partner. For some couples, this was the first time they ever openly discussed sex with their partner. One couple that experienced improved communication explained:

We can talk about matters in this interview that we can’t speak in public. And you give a chance to express our own feelings and then we become tension free. Experience means we were not talking about this subject before participating in this study but now we speak. (couple 69, Anu, wife, age 30)

I felt … awkward at [the] beginning. I speak frankly now … (couple 69, Ravi, husband, age 28)

A wife described how participation in the study hastened discussion about HIV, where previously, the couple had no knowledge:

Now we can talk about this subject with each other. Since now we know the reasons for HIV and much more about this subject we can talk with each other. Otherwise earlier we both had no knowledge of this topic … (couple 50, Rekha, wife, age 33)

Many of the couples whose participation in the acceptability study enhanced their sexual communication expressed their appreciation for a space where they could discuss sex openly and resolve doubts or questions they had about sex. Men and women alikedescribed a sense of release or relief after participation in the interviews, as if a mental burden was lifted from their minds. One husband explained:

… the questions which are asked … are about husband and wife’s sexual relations … you discuss it here openly … I liked it. … Most of the time these questions are buried in our minds. Here we can discuss it open-mindedly and also we get answers to our question[s]. Our doubts get resolved. (couple 34, Kavish, husband, age 37)

Two different husbands recognised that discussing sex was important for women, because Indian culture does not allow them to do so:

You talk separately with us. I like it very much because even though a person is educated s/he doesn’t speak openly about her or his sexual relations. Another thing is that women can not speak such things to someone unknown to them because this is Indian culture. So I liked that you talk [with] each couple separately. (couple 67, Sanjay, husband, age 40)

… my wife blushed a little … she is illiterate, inexperienced. We guys can discuss [sex] with each other. But my wife has no friends, so she can’t discuss the matter with anybody. (couple 70, Amar, husband, age 40)

Many couples described a positive effect of participation in the study on their relationship. Increased communication about sex and HIV improved their relationships by alleviating doubts about their partner’s fidelity, increasing sexual activity within the partnership and forgiving their partners. Two couples described this:

In this study we were asked about husband-wife’s relationship. Nobody outside asks like that and also nobody speak[s] like that. … Like how are your relations, so [I] liked this thing. And due to that we learnt about our own relationship. (couple 35, Raj, husband, age 34)

We can speak freely about sexual relations in this interview. We can tell in what way we keep sexual relations. I should discuss with my husband also. How should we keep sexual relations? I can tell him about this issue. (couple 35, Kavita, wife, age 26)

I have noticed that our husband wife relationship is going smoothly now. [We] do not doubt each other. (couple 30, Rajesh, husband, age 42)

I had one experience that we came close to each other. Now there is no tension. I feel that because of this interview study we could come very close to each other … previously I used to keep myself away from him because of his addiction, I did not like this marriage, but I have decided to forget what had happened. Now after the participation I decided to forgive him. (couple 30, Aarti, wife, age 44)

Discussion

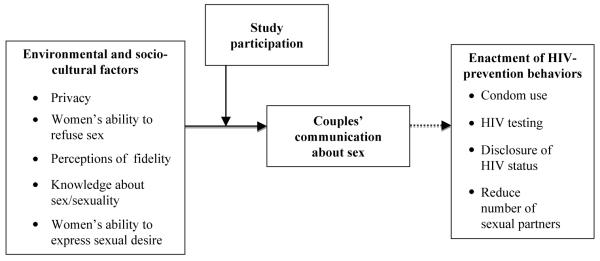

Similar to research findings in other parts of the world, we identified a number of individual, socio-cultural and environmental factors that limited open communication about sexual risk reduction behaviours among married couples in India. Factors included women’s and men’s lack of knowledge about sexuality, sexual power imbalances within relationships and social norms that reinforced these imbalances and physical environments that limited privacy needed to have sex and to discuss sexual matters. The conceptual framework (Figure 1) shows these factors and their influence on couple’s communication. Specifically, privacy, women’s ability to refuse sex, perceptions of fidelity, knowledge about sex and sexuality and women’s abilities to express their sexual desire, along with couples’ participation in the study, influence couples communication. Although we did not measure HIV-prevention behaviours in this study, we hypothesise that couples’ communication in turn influences in the enactment of prevention behaviours, as show in the conceptual framework.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework: sexual communication among married couples in the context of a microbicide clinical trial and acceptability study in Pune, India.

Couples in this study reported that sexuality is a taboo topic, even within marriage. Sexual stereotypes about men and women and misinformation about HIV are perpetuatedby avoiding discussions about sex. Despite the fact that the men and women were highly educated (a majority with 10 or more years of education) many couples had no or very little knowledge about sex and HIV. Women are socialised to repress their sexual desires and prohibited from speaking about them or directly enacting them. Researchers in other settings find that women disconnect from their own sexual desires and subvert their sexuality to conform to social norms (Elliott and Umberson 2008; Koerner and Fitzpatrick 2002; Quina et al. 2000; Rehman and Holtzworth-Munroe 2006). This is reflected by the absence of women’s narratives about sexual desire among the couples, except for when it negatively affects their position in marriage. Even in couples where the wife is more educated than the husband, she still cannot express her sexual desire. The reluctance to discuss sex in marriage is likely associated with lack of understanding of sexuality and is reinforced by social messages that one should not discuss sex.

Women participants were afraid to refuse sex because of the consequences for their marital life and their position in society. A majority of the women and a few men stated that if a woman refuses her husband sex, the husband may assume that the wife is unfaithful or feel justified in fulfilling his sexual needs elsewhere. In a study of 44 couples in Tamil Nadu, India women succumbed to sex because of threats from their husbands to seek partners outside of the marriage (SundariRavindran and Balasubramanian 2004). Similarly, recent research with couples about men’s extramarital sex and HIV risk in Mexico and Vietnam found that if a man is not sexually satisfied by his wife, he may seek partners outside of marriage (Hirsch et al. 2007; Phinney 2008). The acceptance of infidelity within marriage is likely influenced by societal norms about the discussion of sex and gendered differences in desire for sex and the ability to control sexual desire.

Other research has documented Indian women’s and men’s reports of forced or non-consensual sex in the context of marriage which increases vulnerability to HIV infection. In-depth interviews with 19 married migrant couples from Uttar Pradesh living in Mumbai showed that half of the women experienced sexual coercion and violence (Maitra and Schensul 2002). In a study of over 6000 married men from Uttar Pradesh, 22% of men reported sexually abusing their wives and sexual abuse of wives was more common among men with extramarital sexual partners (Martin et al. 1999). Where imbalances of power exist in relationships, women may not have a choice about sex. Although this study did not ask specifically about forced or non-consensual sex, further examination of this topic maybe important because of its implications for HIV prevention. Where women are forced to have sex they are less likely to use a condom and more likely to acquire HIV from an infected partner because of injuries associated with non-consensual sex. Not all men force their wives to have sex and half of the men in the present study sought their wives’ permission to have sex. Furthermore, some men also felt obligated to have sex with their wives when they desire, however, the obligation to have sex was different for men and women. Women submitted to sex to preserve their marital relationship or avoid accusations of infidelity, whereas men felt obligated to have sex to keep their wives happy.

Sexual communication is an important component of HIV prevention and a necessary pre-cursor for condom use. This study found few spaces where couples were able to discuss sex openly. Publicly, sex is an extremely sensitive topic and a proper woman and wife is not expected to discuss sex with her husband (Gage 1998; Sivaram et al. 2005). Even where sex is sanctioned (e.g. within marriage), couples face limited opportunities for privacy because of shared bedrooms or of elders’ influence over access to privacy (Daniel et al. 2008; Lambert and Wood 2005). Among the couples, lack of privacy is a barrier to sexual communication, as are social and cultural taboos regarding discussion of sex within marriage, particularly for women. The inability to discuss sex potentially increases couples’ vulnerability for HIV infection.

Some investigators have suggested that participation in clinical or behavioural research is akin to an intervention (Minnis and Padian 2005; Severy et al. 2005). Indeed, half of the couples in this study described enhanced communication about sex and HIV and AIDS after participation in the study. Two couples specifically mentioned discussing HIV and AIDS with their partners. During in-depth interviews, couples reported increased communication about sex and HIV and AIDS, improved relationships by alleviating doubts about their partner’s fidelity, increased sexual activity in the partnership and forgiving their partners. Similar changes occurred among 120 women participating in another microbicide trial in South Africa. Women in that study reported increased partner involvement in sexual decision making, increased use of male condoms and that they were empowered to negotiate sex (Guest et al. 2007). Likewise, women enrolled in microbicide clinical trials in South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia and Uganda felt empowered through increased knowledge about HIV-prevention methods and created spaces to discuss sex with their partners, which in turn improved trust in their relationships (Montgomery et al. 2008). Because this study is based on secondary analyses of interviews with couples and the interviews were not intended to be an intervention, the findings should be interpreted with caution. However, the couples did express that the simple act of discussing sex and ways to prevent HIV motivated them to broach the subject with their spouses.

Finding ways to improve couples’ sexual communication patterns may be the key to HIV prevention efforts. For example, several studies find that a woman’s ability to refuse sex is a necessary prerequisite for negotiation with a husband of other reproductive health issues, such as contraceptive use (Becker 1996; Blanc and Wolff 2001). Furthermore, where communication about sex is acceptable and partners are able to effectively communicate, couples are more likely to enact preventive behaviours, such as condom or other contraceptive use or HIV testing (George 1998; Montgomery et al. 2008; Severy et al. 2005). The lack of direct, verbal communication among couples in this study limits their ability to discuss important reproductive goals, such as childbearing, contraceptive use and HIV prevention.

Our qualitative study is limited by its size and context. The sample is purposive and was recruited through a clinical trial network and, therefore, women and men participating in this study may be different from other men and women from Pune. Because theinterviews are qualitative and are based on a small sample recruited within a microbicide trial and acceptability study, they are not intended to be representative of the population of Pune. This sample is likely more educated, has a higher income and may be more educated about health issues in general because of their willingness to participate in the studies. However, the findings from this particular context and setting are useful for understanding couples’ sexual communication, even if they cannot be generalised to other populations and cultures.

Conclusion

The findings from this study are important because they elucidate several ways that interventions can increase communication about sex among married couples. The created spaces to talk about sexuality openly and ask frank questions about sexual and reproductive health were novel to the couples and they appreciated the opportunity to discuss these issues. Several couples reported that the interviews prompted them to talk about sex with one another and, for some of them, this was the first time they had ever discussed sex, even though they had been married for several years. Although couples were interviewed separately, they reported discussing HIV and sex with one another afterwards. The findings suggest that culturally appropriate interventions might target men and women separately, to impart similar information about reproductive health and ways to facilitate sexual communication within the couple.

This study reveals that simple discussions about sexuality and HIV prevention with couples can stimulate further discussion in the couple. Creating socially and culturally acceptable safe spaces for couples where men and women are able to ask frank questions about HIV and AIDS, sex and sexuality can potentially improve couples’ communication about sex. Couples interventions addressing the ability to refuse sex in marriage, gender stereotypes about sex and sexuality and suspicions of infidelity within marriage could serve to improve married Indian couples’ communication about sex and, consequently, reduce their risk for HIV infection and help them meet their reproductive goals.

Resumen.

Los estudios previos en la India indican que hay poca comunicación sobre las relaciones sexuales en el matrimonio. La falta de comunicación sobre conductas sexuales seguras podría hacer aumentar la vulnerabilidad de las parejas frente al VIH. En este estudio analizamos cuál es el nivel de comunicación sobre el sexo de las parejas, qué normas socioculturales influyen en las parejas para que hablen sobre las relaciones sexuales y qué repercusiones tiene esto en la prevención del virus del sida. Los datos proceden de entrevistas exhaustivas en dos momentos concretos con 10 parejas. Mediante técnicas de codificación inductiva y deductiva se hicieron análisis cualitativos secundarios de las entrevistas. La mitad de las parejas describieron que hablaban más del sexo, el VIH, y el sida después de haber participado en el ensayo clínico y/o estudio de aceptabilidad. También había aumentado su actividad sexual, las relaciones habían mejorado de modo que se mitigaban las dudas sobre la fidelidad de la pareja, y había más capacidad de perdonar a sus parejas. Los resultados muestran que si se crean espacios seguros donde las parejas puedan plantear preguntas directas sobre el VIH y el sida, el sexo y la sexualidad, se podría mejorar en gran medida la comunicación entre las parejas para hablar del sexo y reducir así el riesgo de infección del VIH.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ward Cates, President of Research, and Kathleen MacQueen of Family Health International for their review of the manuscript. Additionally, we would like to thank Lisa Pearce at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for her comments and review of the manuscript.

References

- Bandura A. Perceived self-efficacy in the exercise of control over AIDS infection. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1990;13:9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Becker S. Couples and reproductive health: A review of couple studies. Studies in Family Planning. 1996;27:291–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg BL. Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. Pearson Education; Boston: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Blanc AK, Wolff B. Gender and decision-making over condom use in two districts in Uganda. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2001;5:15–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carovano K. More than mothers and whores: Redefining the AIDS prevention needs of women. International Journal of Health Services. 1991;21:131–42. doi: 10.2190/VD7T-371M-5G9P-QNBU. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, Coates TJ, Golden E, Dolcini M, Margaret M, Peterson J, Kegeles S, Siegel D, Fullilove D, Thompson M. Correlates of condom use among Black, Hispanic, andWhite heterosexuals in San Francisco: The AMEN longitudinal survey. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1994;6:12–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline RW, Johnson SL, Freeman KE. Talk among sexual partners about AIDS: Interpersonal communication for risk reduction or risk enhancement? Health Communication. 1992;4:39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel EE, Masilamani R, Rahman M. The effect of community-based reproductive health communication interventions on contraceptive use among young married couples in Bihar, India. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2008;34:189–97. doi: 10.1363/ifpp.34.189.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ. Predictors of HIV-preventive sexual behaviour in a high-risk adolescent population: The influence of peer norms and sexual communication on incarcerated adolescents’ consistent use of condoms. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1991;12:385–90. doi: 10.1016/0197-0070(91)90052-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar T, Freimuth VS, McDonald SL, Hammond DA, Fink EL. Strategic sexual communication: Condom use resistance and response. Health Communication. 1992;4:83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott S, Umberson D. The performance of desire: Gender and sexual negotiation in long-term marriages. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:391–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00489.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freimuth VS, Hammond SL, Edgar T, MacDonald DA, Fink EL. Factors explaining intent, discussion and use of condoms in first time sexual encounters. Health Education Research. 1992;7:203–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gage AJ. Sexual activity and contraceptive use: The components of the decision-making process. Studies in Family Planning. 1998;29:154–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangakhedkar R, Bentley M, Divekar A, Gadkari D, Mehendale S, Shepherd M, Bollinger RC, Quinn TC. Spread of HIV infection in married monogamous women in India. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278:2090–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Moreno C, Rodrigues LC. Safer sex and women in Africa. Lancet. 1992;340:57–8. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92475-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George A. Differential perspectives of men and women in Mumbai, India on sexual relations and negotiations within marriage. Reproductive Health Matters. 1998;6:87–96. [Google Scholar]

- George A, Jaswal S. Understanding sexuality: An ethnographic study of poor women in Bombay, India. International Centre for Research on Women; Washington, DC: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gerard M, Gibbons FX, Bushman BJ. Relation between perceived vulnerability to HIV and precautionary sexual behaviour. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;119:390–409. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh J, Wadhwa V, Kalipeni E. Vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among women of reproductive age in the slums of Delhi and Hyderabad, India. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68:638–42. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, Johnson L, Burke H, Rain-Taljaard R, Severy L, vonMollendorf C, VanDamme L. Changes in sexual behaviour during a safety and feasibility trial of a microbicide/diaphragm combination: An integrated qualitative and quantitative analysis. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2007;19:310–20. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.4.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JS, Meneses S, Thompson B, Negroni M, Pelcastre B, Del Rio C. The inevitability of infidelity: Sexual reputation, social geographies and marital HIV risk in rural Mexico. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:986–96. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Coley B. Experimental component analysis of a behavioural HIV-AIDS prevention intervention for inner-city women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:687–93. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.4.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerner AF, Fitzpatrick MA. Nonverbal communication and marital adjustment and satisfaction: The role of decoding relationship relevant and relationship irrelevant affect. Communication Monographs. 2002;69:33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert H, Wood K. A comparative analysis of communication about sex, health and sexual health in India and South Africa: Implications for HIV prevention. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2005;7:527–41. doi: 10.1080/13691050500245818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maharaj P, Cleland J. Risk perception and condom use among married or cohabiting couples in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2005;31:24–9. doi: 10.1363/3102405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maitra S, Schensul SL. Reflecting diversity and complexity in marital sexual relationships in a low-income community in Mumbai. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2002;4:133–51. [Google Scholar]

- Martin SL, Kilgallen B, Tsui AO, Maitra K, Singh KK, Kupper LL. Sexual behaviours and reproductive health outcomes: Associations with wife abuse in India. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:1967–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.20.1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawar N, Mehendale SM, Thilakavathi S, Shepherd M, Rodrigues J, Bollinger R, Bentley M. Awareness and knowledge of AIDS and HIV risk among women attending STD clinics in Pune, India. Indian Journal of Medical Research. 1997;106:212–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnis AM, Padian NS. Effectiveness of female controlled barrier methods in preventing sexually transmitted infections and HIV: Current evidence and future research directions. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2005;81:193–200. doi: 10.1136/sti.2003.007153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery CM, Lees S, Stadler J, Morar NS, Ssali A, Mwanza B, Mntambo M, Phillip J, Watts C, Pool R. The role of partnership dynamics in determining the acceptability of condoms and microbicides. AIDS Care. 2008;20:733–40. doi: 10.1080/09540120701693974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National AIDS Control Organization . UNGASS country progress report 2008 India. National AIDS Control Organization; New Delhi: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Perlmutter BS, Michal-Johnson P. The crisis of communicating in relationships: Confronting the threat of AIDS. AIDS Public Policy Journal. 1989;4:10–9. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney HM. Rice is essential but tiresome; you should get some noodles’ : Doi moi and the political economy of men’ s extramarital sexual relations and marital HIV risk in Hanoi, Vietnam. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:650–60. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.111534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International . NVivo 8. Doncaster. QSR International; Australia: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Quina K, Harlow LL, Morokoff PJ, Burkholder G. Sexual communication in relationships: When words speak louder than actions. Sex Roles. 2000;42:523–49. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman US, Holtzworth-Munroe A. A cross-cultural analysis of the demand-withdraw marital interaction: Observing couples from a developing country. Journal of Counselling and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:755–66. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickman RL, Lodico M, DiClemente RJ, Morris R, Baker C, Huscroft S. Sexual communication is associated with condom use by sexually active incarcerated adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1994;15:383–88. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(94)90261-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severy LJ, Tolley E, Woodsong C, Guest G. A framework for examining the sustained acceptability of microbicides. AIDS and Behaviour. 2005;9:121–31. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-1687-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran P, Abraham C, Orbell S. Psychosocial correlates of heterosexual condom use: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125:90–132. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivaram S, Johnson S, Bentley ME, Go VF, Latkin C, Srikrishnan AK, Celentano DD, Solomon S. Sexual health promotion in Chennai, India: Key role of communication among social networks. Health Promotion International. 2005;20:327–33. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dai012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DJ. Modern marriage, men’ s extramarital sex, and HIV risk in southeastern Nigeria. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:997–1005. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SriKrishnan A, Hendriksen E, Vallabhaneni S, Johnson SL, Raminani S. Sexual behaviours of individuals with HIV living in South India: A qualitative study. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2007;19:334–45. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.4.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SundariRavindran T, Balasubramanian P. ‘ Yes’ to abortion but ‘ No’ to sexual rights: The paradoxical reality of married women in rural Tamil Nadu, India. Reproductive Health Matters. 2004;12:88–99. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(04)23133-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolley E. Sustained acceptability of Tenofovir microbicide gel: Male and female perspectives in Pune, India. Family Health International; Durham, NC, USA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tolley EE, Eng E, Kohli R, Bentley ME, Mehendale S, Bunce A, Severy LJ. Examining the context of microbicide acceptability among married women and men in India. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2006;8:351–69. doi: 10.1080/13691050600793071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardlow H. Men’ s extramarital sexuality in rural Papua New Guinea. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:1006–14. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]