Abstract

This article describes the results of the Interventions to Safeguard Safety breakout session of the 2011 Academic Emergency Medicine (AEM) consensus conference entitled “Interventions to Assure Quality in the Crowded Emergency Department.” Using a multistep nominal group technique, experts in emergency department (ED) crowding, patient safety, and systems engineering defined knowledge gaps and priority research questions related to the maintenance of safety in the crowded ED. Consensus was reached for seven research priorities related to interventions to maintain safety in the setting of a crowded ED. Included among these are: 1) How do routine corrective processes and compensating mechanism change during crowding? 2) What metrics should be used to determine ED safety? 3) How can checklists ensure safer care and what factors contribute to their success or failure? 4) What constitutes safe staffing levels / ratios? 5) How can we align emergency medicine (EM)-specific patient safety issues with national patient safety issues? 6) How can we develop metrics and skills to recognize when an ED is getting close to catastrophic overload conditions? and 7) What can EM learn from experts and modeling from fields outside of medicine to develop innovative solutions? These priorities have the potential to inform future clinical and human factors research and extramural funding decisions related to this important topic.

The 2001 Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) landmark publication, “Crossing the Quality Chasm,” called for reform of the American health care system to ensure that all Americans receive quality care and defined six domains of quality: safety, patient-centeredness, timeliness, efficiency, effectiveness, and equity.1 Emergency department (ED) closures, limited access to primary care, and population expansion within the United States are well documented, with subsequent increases in ED visits and increasing ED lengths of stay.2,3 Over the past decade, multiple studies have shown an association between ED crowding and the negative effect on quality of emergency care. The majority of these studies demonstrate associations with delays in the timeliness of care.4–7 However, a growing body of literature also demonstrates the negative effect that crowding has on the other quality domains, including patient-centeredness and effectiveness.8–12

The definition of ED crowding, the study of its contributing factors, and its quantification have undergone a great deal of scrutiny and refinement over the past decade. The input, throughput, output model postulated by Asplin et al.13 now serves as the predominant paradigm for discussing crowding. Emergency medicine (EM) researchers and an increasing number of policy-makers now agree that ED crowding results from a complex interplay of multiple factors and is primarily related to overall hospital crowding.11,13–17

Similarly, the definition of patient safety has evolved over time. The IOM states that health care should be safe and defines safe care as the avoidance of injuries to patients from the care that is intended to help them.1 However, harm can occur without errors, and errors can occur without harm. Thus, since 2001, the concept of safety has expanded from this overly simplified definition of the absence of harm to a broader concept that includes examining what goes right, how to replicate those positive solutions (positive deviance), and evaluating and utilizing resilience of the systems.18

To date, a paucity of data exists to chronicle the effect of crowding on patient safety in the ED setting. Fewer studies still have evaluated the efficacy of interventions aimed at mitigating the effect of crowding in the ED on patient safety beyond using alternate sites for treating or boarding patients.19,20

The ultimate solution to mitigate the effect of ED crowding on safety is to eliminate crowding. Until that time, interventions to ensure the delivery of quality care during crowding must be identified, developed, and implemented. As we move further away from achieving the goal of eradicating crowding, there is an evolving and growing interest in mitigating the effect of ED crowding on quality of care. Academic Emergency Medicine (AEM), the journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM), convened a consensus conference entitled “Interventions to Assure Quality in the Crowded Emergency Department” in conjunction with its 2011 SAEM annual meeting. This article describes the results of the “Interventions to Safeguard Safety” breakout session of the consensus conference. The objective of this session was to gather expert opinion to define knowledge gaps and priority research questions related to interventions designed to mitigate the effect of ED crowding on safety. This article summarizes the consensus-based recommendations made by this group and should help inform future research and funding in these areas.

DEFINING THE RESEARCH AGENDA

The AEM consensus conference targeted EM researchers, medical directors, department chairs, hospital administrators, and policy-makers with interests in crowding. We used a modified nominal group technique to develop a set of agreed-upon knowledge gaps and priority research questions for future investigations related to interventions designed to maintain patient safety in the crowded ED. This technique uses a highly structured meeting facilitated by an expert on the topic and consists of multiple rounds (usually two) in which the panelists rate, discuss, and rerate a series of items.21 Due to time constraints at the consensus conference, we applied this technique in stages, prior to and during the conference. A preconference working group was formed to develop a preliminary set of eight priority research questions or knowledge gaps to be presented at the safety breakout session of the AEM consensus conference. The preliminary research agenda was presented to the breakout session attendees who were encouraged to develop additional questions. From this all-inclusive list, breakout session attendees voted to establish a final set of six to eight priority research questions or knowledge gaps.

PRECONFERENCE SAFETY WORKING GROUP

Participants

Experts in ED crowding, patient safety, and systems engineering were invited to participate in the preconference working group. Potential participants were identified by the conference chairs through prior publication in these arenas, recommendations from the SAEM Crowding Interest Group, and direct contact of specific patient safety and systems engineering specialists, to obtain an 11-member group representative of key stakeholders (listed in the footnotes).

Assessment of Current Knowledge

The preconference working group addressed the following open-ended questions through several rounds of communications via e-mail and conference calls: 1) what are the current knowledge gaps related to interventions aimed to safeguard safety in the crowded ED? and 2) what are the highest priority research questions related this issue?

Knowledge Gaps Identified by the Preconference Working Group

The working group recognized early in this process that while there is a growing body of literature documenting the harmful effects of crowding, there is a paucity of data assessing its effects on patient safety or interventions to mitigate potential deterioration of patient safety. Furthermore, it is unlikely that many interventions designed to maintain safe conditions would apply only during crowded times. Thus, the working group’s efforts focused on identifying knowledge gaps and prioritizing interventions that were likely to be most beneficial during crowded periods. The working group categorized these into basic knowledge, theoretical knowledge, and applied knowledge as follows:

-

Basic knowledge

Fundamental research on how people recognize problems, negotiate tradeoffs among competing goals, and work around constraints. Understanding these processes should ultimately lead to interventions that make those constraints, problems, and conflicts (and their consequences) more visible and salient and help to better support frontline workers in these situations.

Rather than using metrics that involve errors or adverse events (which are terminal events after a long network of causal influences, and are difficult to count since an improved culture is likely to result in increased reporting), identification of metrics that indicate how close to the boundary of failure the system is might ultimately be more useful.

Introducing a broader definition of translational research may provide novel means of investigation. Translational research is most commonly assumed to equate to bench to bedside translation, but within the positivist, deductive, verification, and validation areas of scientific activity. Including translation from nonpositivist, inductive, interpretative forms of science, such as the safety sciences, may ultimately provide valuable insight.

-

Theoretical knowledge

Characteristics of EDs where crowding does not affect patient safety (positive deviance analyses).

-

Applied knowledge

Applied knowledge includes applying well-established information from “book to bedside” and formally testing theoretical work. Some examples might include:

-

Technology

Trigger methodology / information technology alerts to notify staff of patient deterioration, designed to minimize alarm fatigue.

Wireless wrist bands that monitor vital signs.

-

Staffing

Protocols that match staffing to acuity and patient volume levels or have on-call staff for high demand periods.

Experiences with physician-in-triage and / or nurse greeters (an experienced RN who serves to minimize the hazard of delays caused by prolonged door-to-triage time intervals, to expedite rapid electrocardiograms, etc.) prior to formal triage.

Physician / nursing staffing levels (and flexibility in times of crowding).

Additional laboratory and / or radiology personnel when needed.

-

Protocols / guidelines / checklists

Nurse reassessment of patients in waiting room.

Full capacity / surge protocols during high demand periods.

Procedure checklists to ensure procedures are safely completed.

Medication reconciliation.

Moving admitted patients from ED hallway beds to hallway beds on the inpatient units.

Methodology for handling radiology discrepancies (so those pulmonary nodules from the overread do not get lost in the shuffle, etc.).

-

Communication

Interventions and tools to ensure safe transitions, such as from ED to hospital, ED to home, ED to long-term care facility, and emergency medical services to the ED.

Standardized communication tools and strategies to minimize communication failures, such as checklists, situation–background–assessment–recommendation, read-back, etc.

-

Patient flow

Interventions to reduce boarding and inpatient management of boarders.

Strategies for moving ED patients out of hallway beds to placement in ward hallway beds.

-

Resource management

Streamlining processes for obtaining critical resources (blood products, labs, specimen labeling, etc.).

-

Dissemination of knowledge

Encouraging hospitals, medical centers, and emergency medicine groups to disseminate and share their experiences with developing surge plans (both the pros and the cons, what was learned in the process, successes and failures, etc.).

-

Other / miscellaneous

Interventions to facilitate correct diagnoses.

Interventions to reduce cognitive overload and prevent errors.

Quality improvement / process improvement strategies to avoid unwarranted medication administration or interventions not in compliance with certain guidelines, such as the use of intravenous antihypertensive medications in asymptomatic hypertension (i.e., best practices built into electronic medical records).

Interventions to reduce ED violence (patient vs. patient / provider / family members / visitors).

-

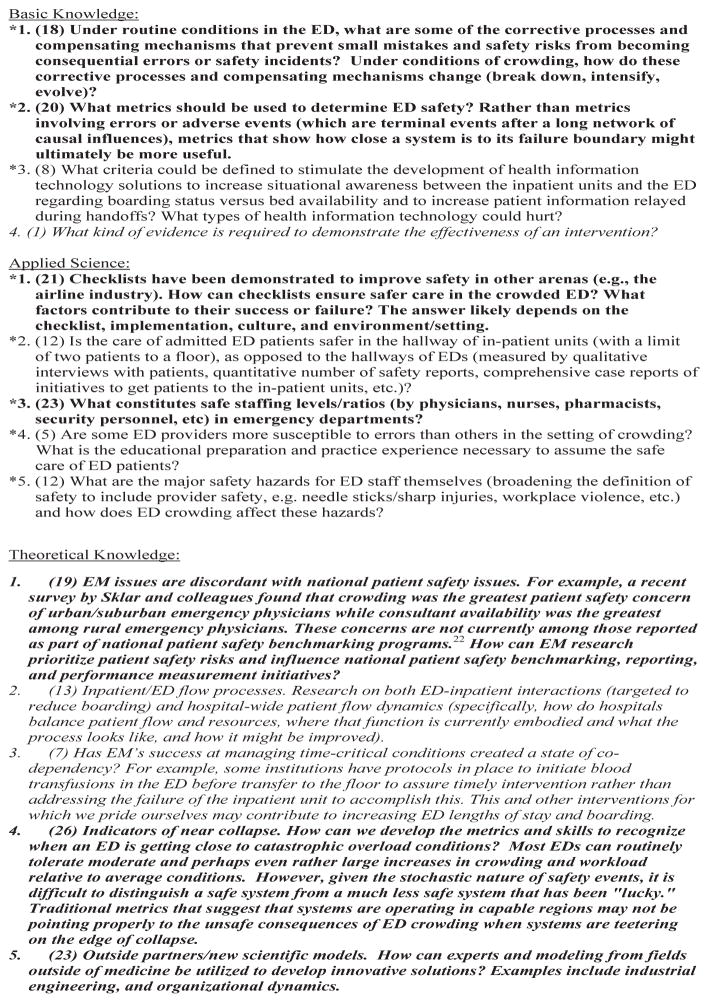

From this list, members of the preconference working group identified eight priority knowledge gaps and research questions (Figure 1, asterisks).

Figure 1.

Complete list of proposed knowledge gaps and research questions developed by the preconference work group and those generated during the breakout session of the consensus conference (those in italics). Consensus conference breakout session participants’ votes are in parentheses before the subject / topic. The top seven vote getters (bold) represent the consensus-derived priority knowledge gaps and research questions.

RESULTS FROM THE CONSENSUS CONFERENCE

Data Collection

The eight priority knowledge gaps and research questions generated by the preconference working group were presented to the 36 attendees of the 1-hour “Interventions to Safeguard Safety” breakout session at the 2011 AEM consensus conference. Of the 36 attendees, five were members of the preconference working group. This allowed those in attendance to engage in an interactive feedback session to clarify each knowledge gap and priority research question and to express their understanding of the logic and relative importance of each item. All proposed knowledge gaps and priority research questions were reviewed and participants were encouraged to provide additional knowledge gaps or priority research questions not previously described.

An inclusive list of knowledge gaps and research questions generated by the preconference working group and refined during the safety breakout session was divided into the same three categories (basic, applied, and theoretical knowledge). Breakout session attendees were asked to vote for up to eight priority knowledge gaps and / or research questions. Voting was anonymous and completed prior to the end of the breakout session. The votes were tallied and those receiving the highest counts represent the consensus-based recommendations (Figure 1).

Consensus-based Recommendations for Research Priorities

Basic Knowledge

Under routine conditions in the ED, what are some of the corrective processes and compensating mechanisms that prevent small mistakes and safety risks from becoming consequential errors or safety incidents? Under conditions of crowding, how do these corrective processes and compensating mechanisms change (break down, intensify, evolve)?

What metrics should be used to determine ED safety? Rather than metrics involving errors or adverse events (which are terminal events after a long network of causal influences and are difficult to count since an improved culture is likely to result in increased reporting), metrics that show how close a system is to its failure boundary might ultimately be more useful.

Applied Knowledge

Checklists have been demonstrated to improve safety in other arenas (e.g., the airline industry). How can checklists ensure safer care in the crowded ED? What factors contribute to their success or failure? The answer likely depends on the checklist, implementation, culture, and environment or setting.

What constitutes safe staffing levels or ratios (by physicians, nurses, pharmacists, security personnel, etc.) in EDs?

Theoretical Knowledge

Emergent patient safety issues are discordant with national patient safety issues. For example, a recent survey by Sklar and colleagues22 found that crowding was the greatest patient safety concern of urban / suburban emergency physicians, while consultant availability was the greatest among rural emergency physicians. These concerns are not currently among those reported as part of national patient safety benchmarking programs. How can EM research prioritize patient safety risks and influence national patient safety benchmarking, reporting, and performance measurement initiatives?

Indicators of near collapse: How can we develop the metrics and skills to recognize when an ED is getting close to catastrophic overload conditions? Most EDs can routinely tolerate moderate and perhaps even rather large increases in crowding and workload relative to average conditions. However, given the stochastic nature of safety events, it is difficult to distinguish a safe system from a much less safe system that has been “lucky.” Traditional metrics that suggest that systems are operating in capable regions may not be pointing properly to the unsafe consequences of ED crowding when systems are teetering on the edge of collapse.

Outside partners and new scientific models: How can experts in modeling from fields outside of medicine be utilized to develop innovative solutions? Examples include industrial engineering and organizational dynamics.

DISCUSSION

The consensus-based recommendations address knowledge gaps at multiple system levels, from the larger ED-inpatient system to individual provider-level interactions. These recommendations also address both basic and applied research directions.

These consensus-based recommendations have several potential limitations. First, although attempts were made to include representatives from key stakeholders, participation may have been biased. While the preconference working group was formed to provide a foundation upon which to build at the consensus conference, it is possible that introduction of the knowledge gaps and research questions posed by this group precluded introduction of additional noteworthy issues, given the time limitation of the discussion at the in-person meeting. The SAEM group is composed of leaders in academic EM, resulting in a lack of representation of nonacademic ED settings. There is a potential for introducing a bias toward recommendations that may only be appropriate for one of the two types of practice settings, given their inherent differences. Additionally, conference attendees were primarily individual investigators who do not represent funding agencies. It is unknown whether the identified priority research questions align with the priorities of potential funding agencies.

CONCLUSIONS

Using a consensus approach, we developed a set of priorities for future research related to interventions to safeguard safety in the crowded ED. These priorities have the potential to improve future clinical and human factors research and extramural funding in this domain.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this conference was made possible (in part) by 1R13HS020139-01 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The views expressed in written conference materials or publications and by speakers and moderators do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. This issue of Academic Emergency Medicine is funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Footnotes

Preconference working group members: Jameel Abualenain, Karen Cosby, Rollin J. (Terry) Fairbanks, Christopher Fee, Kendall Hall, Gail Lenehan, Brad Morrison, Kevin O’Connor, Robert Stephens, Robert Wears, and Barbara Youngberg.

CC session participants: James Amsterdam, Dominik Aronsky, Brent Asplin, Chandra Aubin, William Baker, Christopher Beach, John Becher, Russ Braun, Theodore Christopher, Fergal Cummins, Kevin Ferguson, Christina Gindele, Matthew Gratton, Jason Hack, Leon Haley, Jr., Kendall Hall, Peter Hill, Brian Holroyd, Kurt Isenberger, Renaldo Johnson, John Kelly, Richard Martin, Ryan Mutter, Marie-France Petchy, Timothy Reeder, Drew Richardson, Richard Ruddy, Caitlin Schaninger, Jeremiah Schuur, Robert Sherwin, Robert Shesser, Dell Simmons, and David Sklar.

This manuscript represents the consensus findings for the Interventions to Safeguard Safety component of the 2011 Academic Emergency Medicine Consensus Conference entitled “Interventions to Assure Quality in the Crowded Emergency Department (ED)” held in Boston, MA.

This paper does not represent the policy of either the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). The views expressed herein are those of the authors and no official endorsement by AHRQ or DHHS is intended or should be inferred.

The authors have no disclosures or conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.IOM. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the Twenty-first Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang N, Stein J, Hsia RY, Maselli JH, Gonzales R. Trends and characteristics of US emergency department visits, 1997–2007. JAMA. 2010;304:664–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herring A, Wilper A, Himmelstein DU, et al. Increasing length of stay among adult visits to U.S. Emergency departments, 2001–2005. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:609–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fee C, Weber EJ, Maak CA, Bacchetti P. Effect of emergency department crowding on time to antibiotics in patients admitted with community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:501–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pines JM, Hollander JE, Localio AR, Metlay JP. The association between emergency department crowding and hospital performance on antibiotic timing for pneumonia and percutaneous intervention for myocardial infarction. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:873–8. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.03.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pines JM, Hollander JE. Emergency department crowding is associated with poor care for patients with severe pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCarthy ML, Zeger SL, Ding R, et al. Crowding delays treatment and lengthens emergency department length of stay, even among high-acuity patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:492–503. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernstein SL, Aronsky D, Duseja R, et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on clinically oriented outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richardson DB. Increase in patient mortality at 10 days associated with emergency department overcrowding. Med J Aust. 2006;184:213–6. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sprivulis PC, Da Silva JA, Jacobs IG, Frazer AR, Jelinek GA. The association between hospital overcrowding and mortality among patients admitted via Western Australian emergency departments. Med J Aust. 2006;184:208–12. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoot NR, Aronsky D. Systematic review of emergency department crowding: causes, effects, and solutions. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:126–36. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pines JM, Iyer S, Disbot M, Hollander JE, Shofer FS, Datner EM. The effect of emergency department crowding on patient satisfaction for admitted patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:825–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asplin BR, Magid DJ, Rhodes KV, Solberg LI, Lurie N, Camargo CA., Jr A conceptual model of emergency department crowding. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42:173–80. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khare RK, Powell ES, Reinhardt G, Lucenti M. Adding more beds to the emergency department or reducing admitted patient boarding times: which has a more significant influence on emergency department congestion? Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:575–85. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rathlev NK, Chessare J, Olshaker J, et al. Time series analysis of variables associated with daily mean emergency department length of stay. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:265–71. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asaro PV, Lewis LM, Boxerman SB. The impact of input and output factors on emergency department throughput. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:235–42. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.10.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fatovich DM, Nagree Y, Sprivulis P. Access block causes emergency department overcrowding and ambulance diversion in Perth, Western Australia. Emerg Med J. 2005;22:351–4. doi: 10.1136/emj.2004.018002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor SL, Dy S, Foy R, et al. What context features might be important determinants of the effectiveness of patient safety practice interventions? BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:611–7. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.049379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Viccellio A, Santora C, Singer AJ, Thode HC, Jr, Henry MC. The association between transfer of emergency department boarders to inpatient hallways and mortality: a 4-year experience. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:487–91. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scheuermeyer FX, Christenson J, Innes G, Boychuk B, Yu E, Grafstein E. Safety of assessment of patients with potential ischemic chest pain in an emergency department waiting room: a prospective comparative cohort study. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:455–62. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311:376–80. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7001.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sklar DP, Crandall CS, Zola T, Cunningham R. Emergency physician perceptions of patient safety risks. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:336–40. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]