INTRODUCTION

Kawasaki disease (KD) is typically a self-limiting condition that is a common cause of pediatric vasculitis (1) and the leading cause of pediatric acquired heart disease (2). The disease most frequently occurs in children aged between 6 months and 5 years (3) and is often associated with coronary artery aneurysms (4). Indeed, findings from an epidemiologic survey conducted in Japan revealed that only 1% of KD cases occurred in children aged ≥9 years (5).

There is currently no laboratory test for diagnosing KD. Rather, diagnosis is performed with reference to established clinical criteria (6). Unfortunately, atypical manifestations of KD appear to be on the rise (1), decreasing the likelihood of timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Herein, we report an unusual case of KD: a 10-year-old boy who presented with acute exudative tonsillitis and bilateral cervical lymphadenitis.

CASE DESCRIPTION

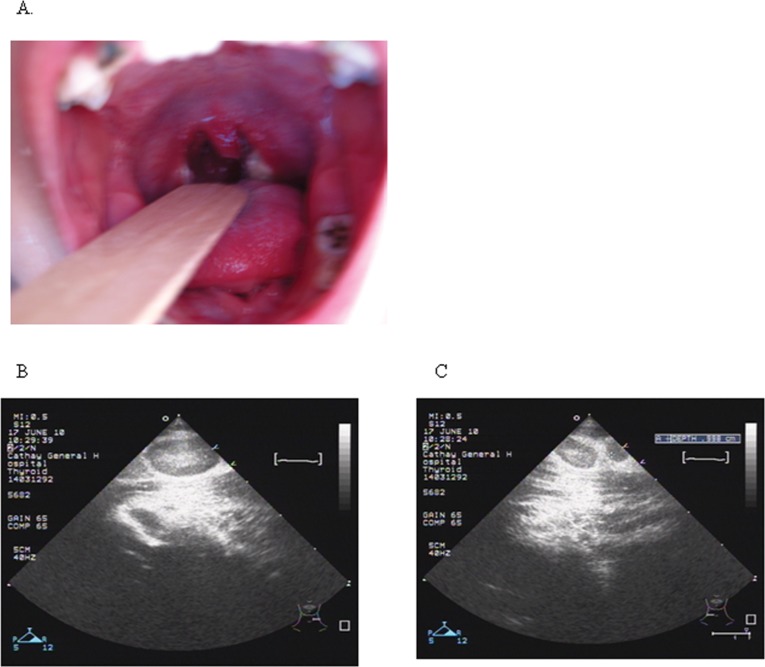

A 10-year-old boy presented with a 4-day history of fever, sore throat, and neck pain. The boy had taken oral medication (acetaminophen, 500 mg QID) before presentation without effect. A physical examination revealed inflamed tonsils with a yellowish purulent coating (Figure 1A) and bilateral neck masses of approximately 5×3 cm2. The neck masses were firm and movable, tender upon palpation, and associated with neck stiffness. There were no other abnormal physical examination findings. Non-specific complaints included cough, rhinorrhea, and abdominal cramping and pain with nausea and vomiting. Blood testing revealed the following: hemoglobin, 14.6 g/dL; white blood cell (WBC) count, 13,720/mm3, with neutrophil predominance (84.3%); platelet count, 197,000/mm3; and C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration, 9.4 mg/dL. Soft-tissue neck films showed no evidence of retropharyngeal abscess or masses, whereas a neck ultrasound revealed bilateral hypoechoic masses suggestive of cervical lymphadenitis (Figure 1B, C). Acute exudative tonsillitis with cervical lymphadenitis was suspected, and treatment with intravenous benzyl penicillin (10×104 U/kg IV Q6H) was initiated.

Figure 1.

The clinical presentation of a 10-year-old boy before treatment. Bilateral injected tonsils with a yellowish purulent coating (A). Ultrasound images of the bilateral neck masses suggested cervical lymphadenitis (B, C).

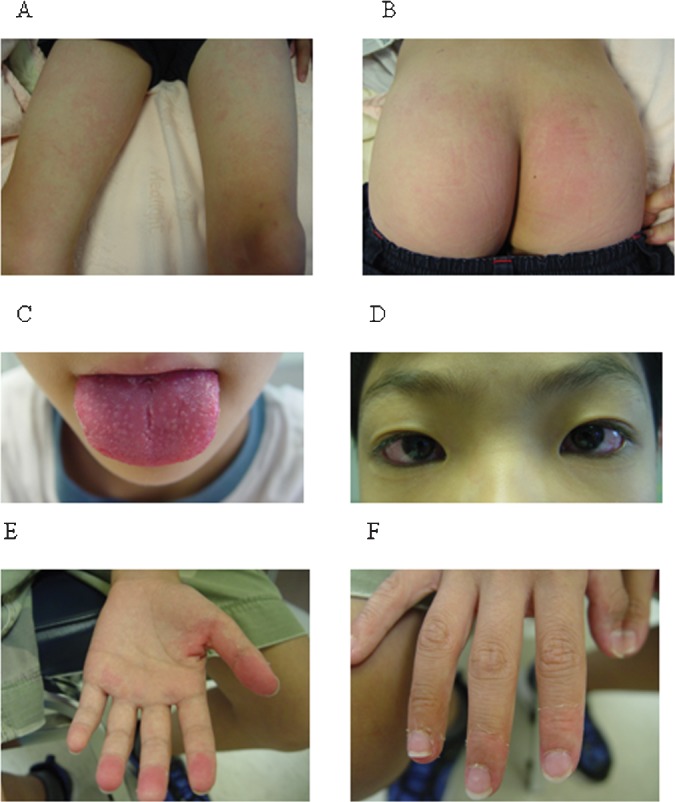

Despite 72 hours of intravenous antibiotic treatment, a persistent high-spiking fever was noted. Three days after admission, the patient developed a rough-textured and sandpaper-like erythematous maculopapular skin rash with pruritus on the lower body (Figure 2A, B). Vesicular and bullous formations were apparent in the axillary region. The skin rash resolved and reappeared intermittently during hospitalization. Four days after admission, the patient developed strawberry tongue and bilateral conjunctivitis (Figure 2C, D). Blood tests performed four and seven days after admission revealed WBC counts of 16,580/mm3 (day 4) and 22,460/mm3 (day 7) and CRP concentrations of 25.7 mg/dL (day 4) and 25.4 mg/dL (day 7). The patient's condition had not improved, and the neck masses remained painful.

Figure 2.

Symptoms during treatment. Maculopapular skin rash with pruritus distributed over the buttocks and lower extremities was apparent 7 days after fever onset (A, B). Strawberry tongue and non-purulent acute conjunctivitis were apparent 8 days after fever onset (C, D). Periungual desquamation of the fingers was apparent 14 days after fever onset (E, F).

Four days after admission, the patient's temperature spiking had not resolved, and he exhibited enlarged cervical nodes and acute exudative tonsillitis. Because the patient had failed to respond to initial therapy with benzyl penicillin within 72 hours, a bacterial-resistant infection was suspected, and the treatment regimen was changed to intravenous amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. The change in medication resulted in a significant improvement of the patient's condition. Seven days after admission, the interval between febrile episodes was prolonged, with lower peak temperatures. Reductions in neck mass size and tenderness were also apparent.

Nine days after admission, the patient's fever had subsided, and all of the other symptoms had resolved. The patient was discharged. Testing before discharge revealed the following: WBC count, 14,410/mm3; platelet count, 508,000/mm3; CRP concentration, 10.7 mg/dL; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 102 mm/h and 112 mm/2 h; and antistreptolysin O and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) antibody titers within normal limits. The throat swab cultures taken at the time of admission were positive for Streptococcus viridans, whereas blood cultures were negative for all organisms.

Fourteen days after the onset of fever, the patient presented to our outpatient department with sheet-like desquamation of the hands, feet, and perianal region (Figure 2E and F). Laboratory analyses revealed normocytic, normochromic anemia (hemoglobin 11 g/dL, hematocrit 34.8%) and thrombocytosis with a platelet count of 718,000/mm3. On the same day, echocardiography revealed bilateral coronary artery dilatation with a right coronary artery aneurysm (Figure 3). The diameters of the dilated vessels were as follows: left main coronary artery (LMCA) 5.2 mm; left anterior descending artery 5.5 mm; left circumflex artery 4.4 mm; and right coronary artery (RCA) 6.5 mm. The patient was diagnosed with KD based on the echocardiographic findings and was readmitted. Immediate treatment with intravenous gammaglobulin was initiated (1 g/kg for 2 days), and the patient was subsequently discharged with a prescription for ongoing treatment with aspirin (5 mg/kg/day) and dipyridamole (6 mg/kg/day). Testing before discharge revealed the following: WBC count, 8,540/mm3; neutrophils, 55.5%; platelet count, 270,000/mm3; and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 8 mm/h and 10 mm/2 h. These findings indicated that the inflammation associated with the disease was controlled.

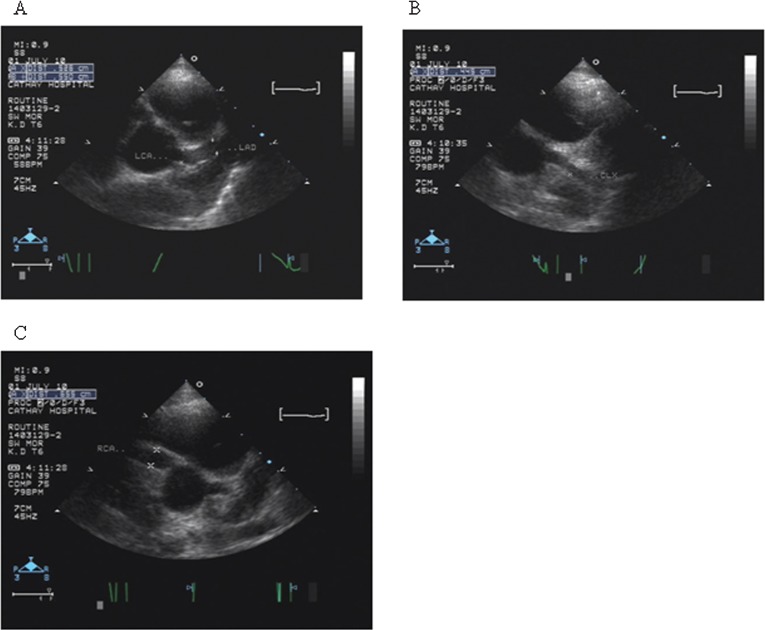

Figure 3.

Echocardiography 20 days after fever onset. A bilateral coronary artery dilatation with a right coronary artery aneurysm is shown: (A) left main coronary artery, 5.2, mm and left anterior descending artery, 5.5 mm; (B) left circumflex artery, 4.4 mm; (C) right coronary artery, 6.5 mm.

Follow-up echocardiography examinations during a 6-month period after discharge revealed diffuse coronary artery dilatation and aneurysms as follows: LMCA 4.8 mm and RCA 6.7 mm (1 month after discharge); LMCA 4.1 mm and RCA 6.2 mm (two months after discharge); and LMCA 3.9 mm and RCA 4.6 mm (six months after discharge).

DISCUSSION

The clinical manifestations of KD can be diverse. Indeed, recent case reports have highlighted atypical cases of KD involving patients presenting with symptoms such as severe shock (7) and pancreatitis (8). A recent case series has also highlighted the existence of KD in adults, indicating that age is not a defining characteristic of the disease (9). It is important that clinicians are made aware of atypical cases to facilitate prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Not all patients with KD have symptoms that meet the classic diagnostic criteria. Children with KD exhibiting fever and fewer than four of the other characteristic symptoms, so-called atypical or incomplete KD, may develop coronary artery aneurysms. In the case described in this paper, a 10-year-old boy presented with fever, acute exudative tonsillitis, and lymphadenopathy. Although fever and lymphadenopathy are well-known symptoms of KD, the patient's age and the lack of other initial symptoms consistent with KD led us to consider other diagnoses, such as group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection or EBV infection, which also cause prolonged fever, lymphadenopathy, and maculopapular skin rash after treatment with antibiotics. To our knowledge, only one other similar case has been described in the literature, which also involved an older child (8 years) who presented with fever, lymphadenopathy, and tonsillitis (10). There have been several other reports describing patients who presented with tonsillar or peritonsillar symptoms in the absence of lymphadenopathy (11-13).

Clinicians need to be aware of the existence of KD and atypical KD and that early treatment is most likely more effective than late treatment. Patients with atypical KD may develop coronary artery damage prior to treatment. Indeed, the atypical presentation of our patient resulted in the delayed diagnosis and initiation of appropriate treatment. Our patient did not meet the classical criteria for the diagnosis of KD until eight days after the onset of fever. Coronary artery aneurysms are relatively common in children with KD who are untreated (14). Our case clearly highlights the importance of early treatment in cases of KD and the need for ongoing echocardiographic monitoring to detect cardiac abnormalities, particularly if the initiation of appropriate treatment has been delayed. Follow-up laboratory testing should also be performed.

Atypical KD is most common in young infants, who are unfortunately at the greatest risk of developing coronary disease. Identifying such cases can be quite challenging, and fatal outcomes have been reported (5). KD should be considered in the differential diagnosis of prolonged fever in infants. Many physicians who are experienced in the diagnosis and treatment of KD at large medical centers have encountered patients in whom prolonged fever was virtually the sole manifestation of KD (15).

In summary, a diagnosis of KD should be considered in children presenting with fever, tonsillitis, and cervical lymphadenopathy, particularly in older children and if empiric antibiotics have proven ineffective. Patients with symptoms suggestive of atypical KD should be referred to a pediatric cardiologist who is experienced in diagnosing this condition.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cimaz R, Sundel R. Atypical and incomplete Kawasaki disease. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2009;23(5):689–97. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Rosa G, Pardeo M, Rigante D. Current recommendations for the pharmacologic therapy in Kawasaki syndrome and management of its cardiovascular complications. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2007;11(5):301–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falcini F, Capannini S, Rigante D. Kawasaki syndrome: an intriguing disease with numerous unsolved dilemmas. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2011;9:17. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-9-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Gerber MA, Gewitz MH, Tani LY, Burns JC, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a statement for health professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart Association. Circulation. 2004;110(17):2747–71. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145143.19711.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yanagawa H, Yashiro M, Nakamura Y, Kawasaki T, Kato H. Epidemiologic pictures of Kawasaki disease in Japan: from the nationwide incidence survey in 1991 and 1992. Pediatrics. 1995;95(4):475–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawasaki T, Kosaki F, Okawa S, Shigematsu I, Yanagawa H. A new infantile acute febrile mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome (MLNS) prevailing in Japan. Pediatrics. 1974;54(3):271–6. Epub 1974/09/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thabet F, Bafaqih H, Al-Mohaimeed S, Al-Hilali M, Al-Sewairi W, Chehab M. Shock: an unusual presentation of Kawasaki disease. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170(7):941–3. doi: 10.1007/s00431-011-1426-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prokic D, Ristic G, Paunovic Z, Pasic S. Pancreatitis and atypical Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2010;8:8. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomard-Mennesson E, Landron C, Dauphin C, Epaulard O, Petit C, Green L, et al. Kawasaki disease in adults: report of 10 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2010;89(3):149–58. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181df193c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hathursinghe HR, Patel S, Uppal HS, Ray J. Acute tonsillitis: an unusual presentation of Kawasaki syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263(4):336–8. doi: 10.1007/s00405-005-1015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korkis JA, Stillwater LB. An unusual otolaryngological problem–mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome (Kawasaki's syndrome) case report. J Otolaryngol. 1985;14(4):257–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rothfield RE, Arriaga MA, Felder H. Peritonsillar abscess in Kawasaki disease. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1990;20(1):73–9. doi: 10.1016/0165-5876(90)90336-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ravi KV, Brooks JR. Peritonsillar abscess - An unusual presentation of Kawasaki disease. J Laryngol Otol. 1997;111(1):73–4. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100136485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suzuki A, Kamiya T, Kuwahara N, Ono Y, Kohata T, Takahashi O, et al. Coronary arterial lesions of Kawasaki disease: cardiac catheterization findings of 1100 cases. Pediatr Cardiol. 1986;7(1):3–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02315475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muise A, Tallett SE, Silverman ED. Are children with Kawasaki disease and prolonged fever at risk for macrophage activation syndrome. Pediatrics. 2003;112(6 Pt 1):e495. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.6.e495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]