Abstract

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) is critical in the regulation of vascular function, and can generate both nitric oxide (NO) and superoxide (O2•−), which are key mediators of cellular signalling. In the presence of Ca2+/calmodulin, eNOS produces NO, endothelial-derived relaxing factor, from L-arginine (L-Arg) by means of electron transfer from NADPH through a flavin containing reductase domain to oxygen bound at the haem of an oxygenase domain, which also contains binding sites for tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) and L-Arg1–3. In the absence of BH4, NO synthesis is abrogated and instead O2•− is generated4–7. While NOS dysfunction occurs in diseases with redox stress, BH4 repletion only partly restores NOS activity and NOS-dependent vasodilation7. This suggests that there is an as yet unidentified redox-regulated mechanism controlling NOS function. Protein thiols can undergo S-glutathionylation, a reversible protein modification involved in cellular signalling and adaptation8,9. Under oxidative stress, S-glutathionylation occurs through thiol–disulphide exchange with oxidized glutathione or reaction of oxidant-induced protein thiyl radicals with reduced glutathione10,11. Cysteine residues are critical for the maintenance of eNOS function12,13; we therefore speculated that oxidative stress could alter eNOS activity through S-glutathionylation. Here we show that S-glutathionylation of eNOS reversibly decreases NOS activity with an increase in O2•− generation primarily from the reductase, in which two highly conserved cysteine residues are identified as sites of S-glutathionylation and found to be critical for redox-regulation of eNOS function. We show that eNOS S-glutathionylation in endothelial cells, with loss of NO and gain of O2•− generation, is associated with impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation. In hypertensive vessels, eNOS S-glutathionylation is increased with impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation that is restored by thiol-specific reducing agents, which reverse this S-glutathionylation. Thus, S-glutathionylation of eNOS is a pivotal switch providing redox regulation of cellular signalling, endothelial function and vascular tone.

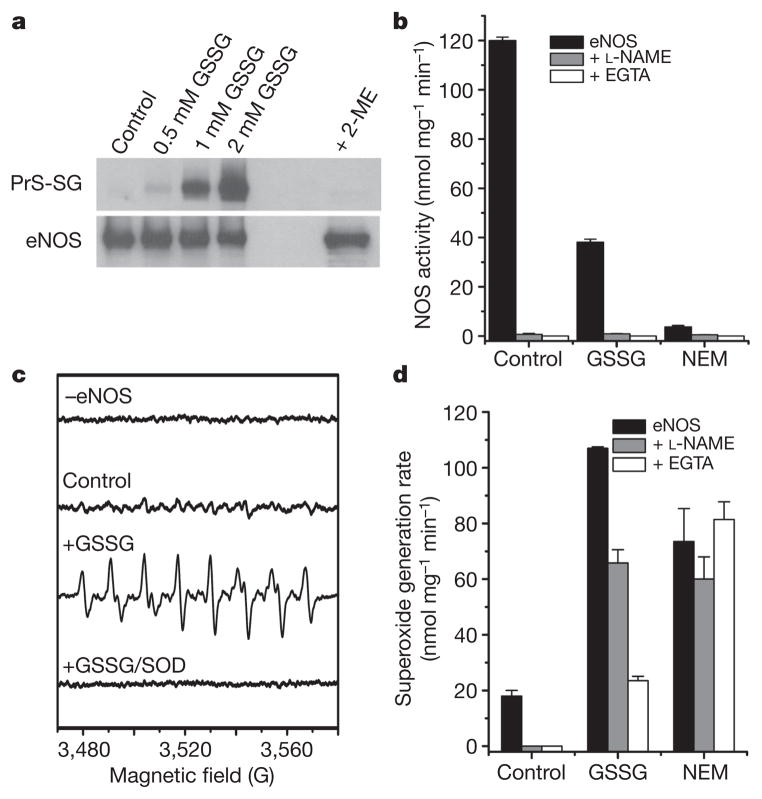

We observed that oxidized glutathione (GSSG) induces dose-dependent S-glutathionylation of human eNOS (heNOS) that was reversed by reducing agents, such as 2-mercaptoethanol or dithiothreitol (DTT) (Fig. 1a). S-Glutathionylation greatly decreased NOS activity (Fig. 1b) in a dose-dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. 1), but this was reversed by DTT with more than 80% recovery. When accessible thiols were alkylated by N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), NOS activity was abolished (more than 95% decrease; Fig. 1b). As expected, the NOS activity of control, S-glutathionylated or S-alkylated heNOS was totally inhibited by the NOS inhibitor L-NG-nitroarginine methyl ester (L-NAME). In contrast to the marked (more than 70%) loss of NOS activity with S-glutathionylation, only a 56% decrease in NADPH consumption was seen that was only partly inhibited by L-NAME or the Ca2+ chelator EGTA (Supplementary Fig. 2). Although thiol-alkylation abolished NOS activity, it decreased NADPH consumption by only about 50%, and this was not inhibited by L-NAME or EGTA. Thus, thiol modification uncouples eNOS with electron leakage from the reductase.

Figure 1. S-glutathionylation of heNOS occurs and inhibits NOS activity.

a, Immunoblotting of heNOS S-glutathionylation. Top: immunoblotting of protein S-glutathionylation (PrS-SG) with anti-GSH antibody. Control non-S-glutathionylated heNOS (1 μg in 20 μl) or heNOS S-glutathionylated by 0.5, 1 or 2 mM GSSG at room temperature (23 °C) for 1 h. Treatment with 2-mercaptoethanol (ME) after S-glutathionylation with 2 mM GSSG reversed the S-glutathionylation. Bottom: immunoblotting with anti-eNOS antibody. b, Effect of S-glutathionylation and S-alkylation on heNOS activity. NOS activity was measured from control, S-glutathionylated (2 mM GSSG for 20 min) or alkylated (1 mM NEM for 20 min) heNOS. NOS activity of treated or untreated heNOS was fully inhibited by L-NAME (1 mM) or EGTA (1 mM). c, d, Effects of S-glutathionylation on O2•− generation from heNOS. O2•− generation was measured from control, S-glutathionylated (as in b) or alkylated (as in b) BH4-bound heNOS by EPR spin trapping with 25 mM 5-diethoxyphosphoryl-5-methyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DEPMPO). c, Spin-trapping showed no signal in the absence of heNOS and only trace signal from control enzyme; S-glutathionylation triggered a marked increase in O2•− generation with a O2•−-adduct spectrum that was quenched by Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD) (200 U ml−1). d, Effect of L-NAME (1 mM) and EGTA (1 mM) on O2•− generation from control, S-glutathionylated and alkylated BH4-bound heNOS. Results in b and d are shown as means and s.e.m. (n = 3–5).

Because electron leakage could trigger O2•− generation, electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spin trapping was performed to demonstrate this S-glutathionylation-dependent O2•− generation from heNOS. S-Glutathionylation greatly increased O2•− generation (more than five-fold) with a prominent O2•−-adduct signal that was quenched by Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase (Fig. 1c). The NOS inhibitor L-NAME, which blocks O2•− generation from the oxygenase, only partly blocked this O2•− generation (Fig. 1d), and it was also incompletely blocked by EGTA. S-Alkylation of heNOS increased O2•− generation (about four-fold), and this was not blocked by L-NAME or EGTA. In contrast, the low-level O2•− production from control heNOS was fully quenched by L-NAME or EGTA. Thus, S-glutathionylation and S-alkylation uncouple heNOS, greatly increasing O2•− generation, and the partial or complete lack of inhibition by L-NAME suggests that the observed O2•− is largely derived from the reductase domain.

To investigate the mechanism of S-glutathionylation-induced heNOS uncoupling, we sought to determine the specific residues modified. We therefore subjected S-glutathionylated heNOS to proteolytic digestion and liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) analysis. Peptides with a mass difference of 305 Da, representing one glutathione moiety, were detected by LC–MS and their primary sequence was determined by MS/MS. We identified two glutathionylated cysteine residues within the reductase domain, namely Cys 689 and Cys 908, from both trypsin and chymotrypsin digestions (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). Using molecular modelling to predict the three-dimensional structure of the heNOS reductase domain (Supplementary Fig. 4), we found that Cys 689 and Cys 908 are located on the domain surface surrounded by several positively charged residues, and thus would probably be deprotonated at physiological pH, making them good candidates for S-glutathionylation.

S-Glutathionylation results in the formation of a mixed disulphide bond between the reactive Cys-thiol and reduced glutathione (GSH), a tripeptide consisting of glycine, cysteine and glutamate. The addition of this bulky negatively charged group can alter protein structure and function in a similar manner to the addition of a phosphate14,15. Our molecular modelling reveals that both Cys 689 and Cys 908 are located at the interface of the FAD-binding and FMN-binding domains. Modification of these residues would therefore disrupt FAD–FMN alignment, interrupting electron transfer between the flavins and enhancing their solvent accessibility16 (Supplementary Fig. 4), so that O2 could gain access and accept an electron from the reduced flavin, with the formation of O2•−.

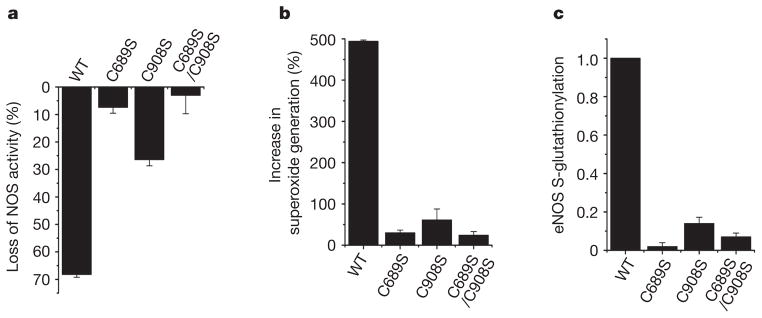

Mutagenesis of Cys 689 or Cys 908 to Ser was used to test the importance of these residues on the redox regulation of eNOS. Whereas wild-type (WT) heNOS is S-glutathionylated by GSSG with a roughly 70% loss of NOS activity, Cys→Ser mutants resist glutathionylation, with no loss of NOS activity in the double mutant and only modest loss in the single mutants (Fig. 2a–c). These mutants also resist GSSG-induced eNOS uncoupling with O2•− generation. Thus, both Cys 689 and Cys 908 are critical for the redox regulation of eNOS.

Figure 2. Cysteine mutants (C689S, C908S and C689S/C908S) of heNOS resist S-glutathionylation and secondary uncoupling.

WT heNOS and heNOS C689S, C908S and C689S/C908S mutants were treated with 2 mM GSSG. a, Percentage loss of NOS activity after treatment of heNOS with GSSG. b, Percentage increase in O2•− generation after treatment of heNOS with GSSG. c, Ratio of relative eNOS S-glutathionylation to eNOS protein. The relative intensity of eNOS S-glutathionylation/eNOS protein was normalized to the wild-type value. The Cys→Ser mutants maintained a NOS activity similar to that of the wild type (120 ± 12 n mol min−1 mg−1). Results are shown as means and s.e.m. (n =3).

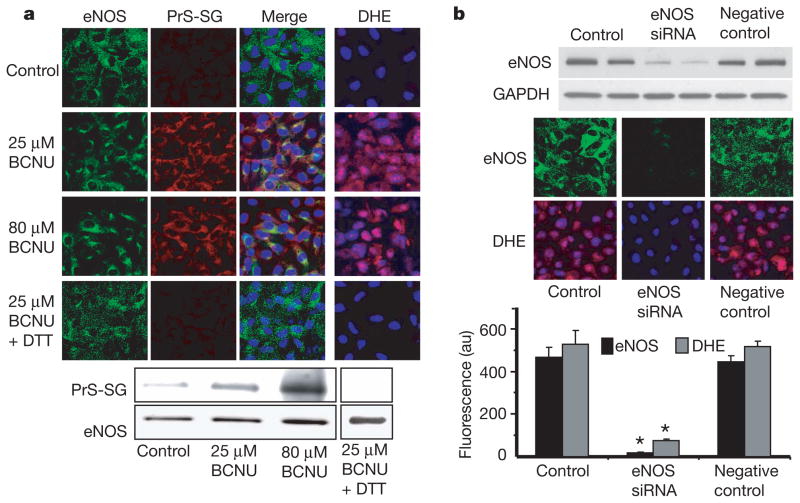

Next we sought to determine the consequences of eNOS S-glutathionylation in endothelial cells. Inhibition of glutathione reductase by 1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea (BCNU) decreases the cellular GSH/GSSG ratio, leading to protein S-glutathionylation17,18. Previous studies of bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs) treated with BCNU reported eNOS inhibition with glutaredoxin or thioredoxin inactivation19,20; however, the molecular mechanism of this process and alterations in eNOS were not investigated. In our current study of BAECs treated with BCNU, confocal microscopy demonstrated marked cellular S-glutathionylation that co-localized with eNOS (Fig. 3a, left columns). Immunoprecipitation of eNOS followed by immunoblotting confirmed that the BCNU-induced increase in GSSG led to eNOS S-glutathionylation (Fig. 3a, bottom). This was further confirmed by mass spectrometry, in which Cys 689 was more than 50% S-glutathionylated (Supplementary Fig. 5). BCNU-treated BAECs showed increased O2•− generation that was blocked by DTT, which reversed the eNOS S-glutathionylation (Fig. 3a, right column, and Supplementary Fig. 6). BCNU also dose-dependently decreased cellular eNOS-derived NO production (Supplementary Fig. 7). Thus, alterations in the cellular GSH/GSSG ratio led to the S-glutathionylation of eNOS, and this resulted in decreased NO and increased O2•− generation. eNOS gene silencing from BAECs abolished BCNU-induced O2•− generation (Fig. 3b). Experiments in COS7 cells transfected with WT or C689A/C908A eNOS confirmed that glutathionylation at Cys 689/Cys 908 is critical for the triggering of BCNU-induced O2•− generation (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Figure 3. Effect of redox stress on eNOS S-glutathionylation and function in endothelial cells.

a, Immunostaining of eNOS (left column, green fluorescence) and S-glutathionylation (second column, red fluorescence) in control BAECs and cells preincubated with BCNU. The third column shows the merged S-glutathionylation/eNOS image along with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining of the nucleus (blue). eNOS staining and S-glutathionylation seem to co-localize. The right-hand column shows O2•− detection with dihydroethidine (DHE), which is oxidized by O2•− to a product with red fluorescence, and the cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Increased O2•− generation was seen in the BCNU-treated cells. Bottom: immunoprecipitation of eNOS from the BCNU-treated cells shows that eNOS S-glutathionylation occurs but is reversed by 1 mM DTT. The upper row shows immunoblotting with anti-GSH antibody; the lower row shows immunoblotting with anti-eNOS antibody. b, Effects of eNOS silencing from BAECs on BCNU-induced O2•− generation. Top: immunoblotting against eNOS to determine the efficiency of eNOS silencing. Middle: confocal microscopy of eNOS (upper row) and O2•− measurements with DHE (lower row). NOS3 short interfering RNA (siRNA) greatly decreases eNOS expression in BAECs (middle column). Bottom: graph of the effect of eNOS silencing on BCNU-induced O2•− generation. Results are shown as means and s.e.m. (n =5). Asterisk, P < 0.001.

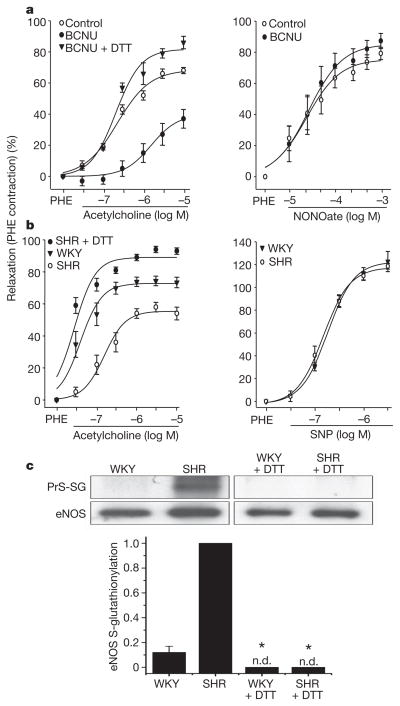

To further determine whether redox stress leading to S-glutathionylation alters endothelial function in vessels, aortic segments were pre-exposed to BCNU and then measurements of endothelium-dependent or endothelium-independent relaxation were performed. In BCNU-exposed vessels, a marked decrease in endothelium-dependent vasodilation was seen (Fig. 4a, left panel), whereas endothelium-independent vasodilation elicited by exogenous NO was unaffected (Fig. 4a, right panel). Furthermore, DTT, which reverses eNOS S-glutathionylation, restored endothelium-dependent vasodilation in BCNU-treated vessels.

Figure 4. Effect of redox stress on eNOS S-glutathionylation and function in vessels.

a, Endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent vasorelaxation in control and BCNU (80 μM)-treated rat aortic rings. BCNU markedly decreased endothelium-dependent relaxation to acetylcholine (left panel) but not endothelium-independent relaxation by the NO donor NONOate (right panel). DTT (1 mM for 20 min) reversed the BCNU-induced inhibition of relaxation (left panel). Aortic relaxation is plotted as the percentage decrease in phenylephrine (PHE)-induced contraction against agonist concentration on a logarithmic scale. Results are shown as means ± s.e.m.; P < 0.05, BCNU versus control or BCNU + DTT (n =4). b, Endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) and control (WKY) aortic rings. SHR rings showed a marked decrease in relaxation to acetylcholine; however, DTT (as above) re-established the acetylcholine response. Endothelium-independent relaxation (right) was similar for both SHR and WKY rings. Aortic relaxation is expressed as in a. P < 0.05, SHR versus WKY or SHR + DTT (n =4). See also Supplementary Fig. 10. c, eNOS S-glutathionylation of SHR and WKY aortae. Top: WKY and SHR aortae, either untreated or DTT-pretreated as in b, were homogenized. This was followed by immunoprecipitation with anti-eNOS antibody. The immunoprecipitation products were separated by SDS–PAGE followed by immunoblotting against anti-GSH and anti-eNOS antibodies. In SHR aortae, eNOS S-glutathionylation was markedly increased compared with WKY aortae and was abolished by pretreatment with DTT. Bottom: ratio of relative intensity of eNOS S-glutathionylation/eNOS, normalized to SHR aortae. There is only trace eNOS S-glutathionylation in WKY aortae, whereas high levels are seen in SHR aortae. There was no detectable (n.d.) NOS S-glutathionylation in DTT-pretreated WKY or SHR aortae. Asterisk, P < 0.001 versus SHR (n =5).

Oxidant-stress-induced disruption of endothelium-dependent vasodilation is involved in the pathogenesis of hypertension, atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular disease21. Because eNOS S-glutathionylation profoundly impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation, we speculated that there might be an increase in eNOS S-glutathionylation in hypertension. Indeed, in the vessels of spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) rats en face immunohistology showed marked S-glutathionylation with prominent endothelial co-localization with eNOS (Supplementary Fig. 9), whereas control normotensive vessels (from WKY rats) had little S-glutathionylation. Immunoprecipitation of eNOS confirmed these results, showing much higher eNOS S-glutathionylation in vessels from SHR rats in comparison with vessels from WKY rats (Fig. 4c). The marked decrease in endothelium-dependent vasodilation of aortic rings from SHR rats was reversed by thiol-specific reducing agents that concurrently reverse eNOS S-glutathionylation (Fig. 4b, c). Thus, just as in the in vitro and ex vivo settings, eNOS S-glutathionylation occurs in vessels in vivo and increases with oxidative stress, resulting in a loss of endothelium-dependent relaxation, leading to hypertension. Other redox modifications of critical thiols on eNOS or other important regulatory proteins could further contribute to vascular dysfunction and the pathogenesis of hypertension22,23.

There is extensive evidence that thiols potentiate eNOS activity and alleviate oxidant stress24,25. NOS uncoupling induces oxidant stress and has previously been shown to occur with depletion of L-Arg or BH4 and elevation of methylarginine levels4,26–28. Here we show that eNOS possesses specific redox-sensitive thiols that are readily S-glutathionylated in endothelial cells and vessels with marked endothelial dysfunction and hypertension. This oxidative modification switches eNOS from its classical NO synthase function to that of an NADPH-dependent oxidase generating O2•−, which occurs primarily from the reductase domain and, in contrast to other uncoupling mechanisms, is not inhibited by typical NOS inhibitors. Because NO and O2•− have many opposing roles in cell signalling and vascular function29, S-glutathionylation of eNOS will trigger profound changes in cellular and vascular function and will mediate redox-signalling under oxidative stress. This mechanism of eNOS uncoupling could be triggered by other uncoupling processes such as BH4 depletion, but could also further enhance BH4 depletion. Further studies will be needed to elucidate these interactions.

These observations provide a new molecular understanding of how oxidant stress alters endothelial function and vascular tone and how the restoration or supplementation of reducing equivalents can restore endothelial function and normalize vascular tone. Therapeutics with thiol-reducing properties can therefore now be developed and refined as potent drugs for reversing endothelial dysfunction and ameliorating hypertension and other cardiovascular disease. Recently, hydrogen sulphide, a potent reducing agent, has been identified as a critical endogenous signalling molecule conferring potent cardiac protection in diseases with oxidant stress30; however, its mechanism of action is unknown. Our present observations provide a mechanism by which it might confer protection.

S-Glutathionylation thus uncouples eNOS, switching it from NO to O2•− generation. This process is induced by oxidant stress and is reversible. Two highly conserved cysteine residues at the interface between the FMN-binding and FAD-binding domains are S-glutathionylated, leading to uncoupling with O2•− generation. Oxidant stress triggers eNOS S-glutathionylation in endothelial cells and intact vessels. Furthermore, S-glutathionylation is increased in hypertensive vessels, resulting in impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation. In view of the central importance of NO and eNOS-mediated endothelial dysfunction in diseases including heart attack, stroke, diabetes and cancer, identification of this novel redox-signalling pathway provides new insights into therapeutic approaches for the prevention or amelioration of many of the most prevalent diseases afflicting mankind.

METHODS

heNOS purification

heNOS was purified from an Escherichia coli overexpression system in which plasmids expressing heNOS (pCWheNOS or pDEST17heNOS) and calmodulin (pCaM) were co-transformed into BL21(DE3). The detailed expression procedures have been described previously15,31.

Determination of protein and haem content

Protein concentration of purified heNOS was determined by the Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad), with BSA as a standard. The haem content of heNOS was determined by pyridine haemochromogen assay. heNOS (50 μg) was added to a solution containing 0.15 M NaOH and 1.8 M pyridine, and the difference spectrum (reduced minusoxidized bispyridine haem)was recorded and quantified by using Δε 524 mM−1 cm−1 at 556–538 nm. Reduction of the bispyridine haem was achieved by the addition of a few grains of dithionite15,32.

Thiol modification of heNOS

To induce protein S-glutathionylation in vitro, purified heNOS was incubated for 20 min with the specified GSSG concentration in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4 at room temperature33. To alkylate all accessible thiols on heNOS, the purified heNOS was incubated for 20 min with 1 mM NEM in 50 mM Tris pH 7.4 at room temperature. Thiol modified enzyme preparations were then subjected to further analysis: immunoblotting, NO activity assay, and NO and O2•− measurement4,15,26,34–37. For mass spectrometric identification of sites of S-glutathionylation, heNOS was incubated for 1 h with 2 mM GSSG at room temperature and then subjected to SDS–PAGE separation under non-reducing conditions. The molar ratio of eNOS to GSSG was 1:250 when 2 mM GSSG was used for the reaction.

Measurement of NOS activity

NOS activity was measured by the conversion of L-[14C]arginine to L-[14C]citrulline in a total volume of 200 μl of buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 100 μM L-Arg, 1 μM L-[14C]arginine, 0.5 mM NADPH, 0.5 mM Ca2+, 10 μg ml−1 calmodulin, 10 μM BH4 and 5 μg ml−1 purified eNOS. After incubation for 10 min at 37 °C, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 3 ml of ice-cold stop buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 5.5, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA). L-[14C]Citrulline was separated by passing reaction mixtures through Dowex AG 50W-X8 (Na+ form; Sigma) cation-exchange columns and quantified by liquid scintillation counting34.

Measurement of NADPH consumption

NADPH oxidation28 was followed spectrophotometrically at 340 nm with a Varian Cary 300 UV-Vis spectrophotometer. The reaction mixture (total volume 500 μl) contained 10 μg of CaM, 100 μM L-Arg, 200 μM NADPH, 10 μM BH4 and 500 μM CaCl2 in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4. heNOS (2–5 μg) was used in the NADPH consumption assay. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 10 μl of 10 mM NADPH, and all experiments were run at room temperature. The rate of NADPH oxidation during the first 10 min was followed and the initial rate was calculated from the linear portion and an extinction coefficient of 6.22 mM−1 cm−1.

Measurement of O2•− generation by EPR spin trapping

Spin-trapping measurements of oxygen radical production from heNOS were performed in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 7.4 containing 0.5 mM NADPH, 0.5 mM Ca2+, 10 μg ml−1 calmodulin, 15 μg ml−1 purified heNOS and 25 mM DEPMPO15,37. For these measurements the binding of BH4 to heNOS was reconstituted in advance by incubation of the enzyme with 100 μM BH4 for 3 h; the unbound BH4 was then removed to prevent superoxide scavenging. EPR spectra were recorded in a 50-μl capillary at room temperature with a Bruker EMX spectrometer operating at 9.86 GHz with 100 kHz modulation frequency at room temperature, as described15. Spectra were measured by using the following parameters: centre field 3,510 G; sweep width 140 G; power 20 mW; receiver gain 2 × 105; modulation amplitude 0.5 G; conversion time 41 ms; time constant 328 ms.

SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting

The standard procedures for SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting were followed as described previously15. The reaction mixture was separated on a 4–20% Tris-glycine polyacrylamide gradient gel. Samples were run at room temperature for 1.5 h at 125 V. Protein bands were transferred electrophoretically to a nitrocellulose membrane in 12 mM Tris-HCl, 96 mM glycine, 20% methanol with an Xcell II Blot Module (Invitrogen) with 25 V constant for 90 min. Membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TTBS), with 5% dried milk (Bio-Rad). Membranes were then incubated overnight with anti-glutathione monoclonal antibody (ViroGen) or anti-eNOS polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz) at 4 °C. Membranes were then washed three times in TTBS and incubated for 1 h with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG in TTBS at room temperature. Membranes were again washed three times in TTBS and were then detected with ECL Western Blotting detection reagents (Amersham Biosciences). The signal intensity of blotting was digitized and quantified with ImageJ from the National Institutes of Health.

Mass spectrometry

The protein sample was subjected to SDS–PAGE on a 4–20% gradient polyacrylamide gel. Protein bands on the gel were then stained with Coomassie blue. The band containing S-glutathionylation of heNOS, which was confirmed by immunoblotting against anti-GSH antibody, was cut and digested in-gel with trypsin, chymotrypsin, or trypsin and chymotrypsin before mass spectrometric measurement33.

The S-glutathionylation of heNOS was determined with capillary-liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (Nano-LC–MS/MS), which was performed on a LTQ or LTQ Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo). The detailed parameters used in the MS measurements have been described in our previous study33. Sequence information from MS/MS data was processed with Mascot Distiller software, by using standard data processing parameters. Database searches were performed with the MASCOT (Matrix Science) program.

Modelling

The three-dimensional structure of heNOS reductase domain was predicted by use of the Swiss-Model First Approach Mode38. The input sequence of heNOS starts from Ala 515 to Ser 1177 of heNOS. The lower Blast P(N) limit for template selection was set to 0.00001. The three-dimensional structure of the reductase domain of rat neuronal NOS (PDB ID 1F20) was also used as the self-input template file for the tertiary structure prediction of the heNOS reductase domain. The final model output was a Swiss-PDB viewer project file. PyMOL (DeLano Scientific LLC) was used to construct and view the three-dimensional structure of the heNOS reductase domain.

Site-directed mutagenesis of heNOS

For bacterial expression, the human NOS3 gene was subcloned into pDEST17 vector (Invitrogen). It contains a His tag at the amino terminus of heNOS. The reading frame and heNOS sequence were confirmed by DNA sequencing. QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) was used for heNOS Cys→Ser mutations. Primers for each mutation were as follows: Cys 689→Ser, 5′-GGCGACGAGCTGAGCGGCCAGGAGG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CCTCCTGGCCGCTCAGCTCGTCGCC-3′ (antisense); Cys 908→Ser, 5′-GAAGTGGTTCCGCAGCCCCACGCTGC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GCAGCGTGGGGCTGCGGAACCACTTC-3′ (antisense). The sequence of each heNOS mutant was further confirmed by DNA sequencing. The detailed procedures of protein expression and purification have been described previously15,31.

For mammalian expression, the human NOS3 gene was subcloned into pcDNA-DEST40 gateway vector (pc40heNOS) (Invitrogen). It contains the V5 epitope and a His tag at the carboxy terminus of heNOS. The reading frame and heNOS sequence were confirmed by DNA sequencing. QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) was used for heNOS Cys→Ala mutations. Primers for each mutation were as follows: Cys 689→Ala, 5′-GGCGACGAGCTGGCCGGCCAG GAGG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CCTCCTGGCCGGCCAGCTCGTCGCC-3′ (antisense); Cys 908→Ala, 5′-GAAGTGGTTCCGCGCCCCCACGCTGCTG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CAGCAGCGTGGGGGCGCGGAACCACTTC-3′ (antisense). The sequence of the heNOS double mutant (C689A/C908A) from pc40heNOS was further confirmed by DNA sequencing. For mammalian expression, COS-7 was used for heNOS overexpression for cellular assays, because there is no eNOS in COS-7, as reported previously39.

Fluorescence and immunofluorescence microscopy

BAECs cultured on 22-mm2 sterile coverslips (Harvard Apparatus) in 35-mm sterile dishes at a density of 104 cells per dish were subjected to treatment with BCNU for 4 h. BCNU, an inhibitor of glutathione reductase, has been shown to alter cellular redox environment, leading to an increased GSSG/GSH ratio. The increase in oxidized GSH leads to increased cellular S-glutathiolation. At the end of the experiment, cells attached to coverslips were washed with PBS, fixed for 10 min with 3.7% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized for 5 min with 0.25% Triton X-100 in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.01% Tween 20 (TBST), washed three times, and then blocked for 30 min with 1% BSA in TBST. Permeabilization is required to provide access for the antibody to the antigen throughout the cell. Permeabilization and washing is also critical for the detection of protein-bound GSH adducts, because it clears the free GSH that would otherwise bind the antibody. For detection of S-glutathionylation and eNOS, the fixed and permeabilized cells were incubated at room temperature for 1 h with mouse anti-GSH and rabbit anti-eNOS primary antibodies at a dilution of 1:2,000 in TBST containing 1% BSA, followed by secondary anti-mouse Alexa fluor-568 and anti-rabbit Alexa fluor-488-conjugated antibody (1:1,000 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. The coverslips with cells were then mounted on a glass slide with Fluoromount G mounting medium and viewed with a Olympus FluoView-1000 confocal microscope at × 60 magnification, and data were captured digitally and analysed.

To detect O2•− generation from S-glutathionylated eNOS in BAECs, cells were then incubated with the O2•− indicator 10 μM DHE to detect O2•− in live cells. DHE fluoresces when oxidized by O2•−. Nuclei were stained with blue-fluorescent DAPI (1 μM) for 10 min in the incubator. After incubation, cells were washed with PBS and mounted; images were captured and analysed at × 60 magnification by confocal fluorescence microscopy, and overlaid with LSM software15.

En face sections

After surgery the aortae from WKY and SHR rats were cleaned and washed with ice-cold PBS. A slit was made longitudinally and the opened aortae were fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 3 h at room temperature. The fixed aortae were washed for 2–3 h in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer and then incubated overnight with 2.3 M sucrose gradients titrated for 10 min each with 5% sucrose in cacodylate buffer (2:1, 1:1, 1:2 and 1:3) and 2.3 M sucrose at 4 °C. The samples were then mounted in OCT medium and frozen in liquid nitrogen40. Tissues were cryosectioned en face from anterior to posterior and the sections were probed for eNOS and PrS-SG. The sections were permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 for 10 min and washed, followed by immunostaining for eNOS/PrS-SG as described above. High-magnification images were obtained and analysed with an Olympus FluoView-1000 confocal microscope at ×100 original magnification.

EPR spin-trapping measurement of NO production

Spin-trapping measurements of NO from BAECs were performed with a Bruker EMX spectrometer with Fe-N-methyl-D-glucamine dithiocarbamate (Fe-MGD) as the spin trap35,36. Spin-trapping experiments were performed on cells grown in six-well plates (106 cells per well). Before EPR spin-trapping measurements, control cells or cells treated with BCNU were washed twice with PBS (without CaCl2 or MgCl2). Next, 0.8 ml of PBS containing glucose (1 g l−1), CaCl2, MgCl2, the NO spin-trap Fe-MGD (0.5 mM Fe2+, 5.0 mM MGD) and calcium ionophore (1 μM) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for 20 min at 37 °C in a humidified environment containing 5% CO2/95% O2. After incubation, the medium from each well was removed, and the trapped NO in the supernatants was quantified by EPR. Spectra recorded from these cellular preparations were obtained with the following parameters: microwave power 20 mW; modulation amplitude 4.0 G; modulation frequency 100 kHz.

Aortic preparations and functional measurements

Aortae were excised from anaesthetized and heparinized rats, placed in ice-cold buffer, cleaned of loosely adhering fat and connective tissue and cut into rings 5 mm in length for measurements of vascular tone as described previously, with minor modification41.

In brief, aortic rings were mounted horizontally and connected to an isometric force transducer in organ chambers (Multi Wire Myograph, Model 610M; DMT) filled with 5 ml of Krebs–Henseleit (K-H) buffer (37 °C, pH 7.4) consisting of 118 mM NaCl, 4.6 mM KCl, 1.2 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM NaH2PO4, 24 mM NaHCO3, 18 mM glucose, 10 μM indomethacin and 4.6 mM HEPES bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2. The aortic segments were allowed to equilibrate for 60 min with an initial tension of 1 g. The stability of each ring was checked by the successive administration of 4 M KCl. Preparations were then washed three times with drug-free oxygenated K-H buffer and allowed to relax fully for 15 min before the experimental protocol began. Then the aortic rings were contracted with pheny-lephrine (10 μM) and, after stable contraction, the vasorelaxant effects of cumulative addition of acetylcholine, NONOate or sodium nitroprusside (SNP) were determined by measuring the tension and expressing this as the percentage relaxation with respect to the maximal phenylephrine contraction. To induce S-glutathionylation, rings were pretreated with 80 μM BCNU during the 60 min equilibration period, and to reverse S-glutathionylation the rings were treated with 1 mM DTT for 20 min. Similarly, to reverse the intrinsic S-glutathionylation present, SHR or WKY aortae or aortic rings were treated with 1 mM DTT for 20 min at 37 °C. For immunoprecipitation studies measuring the effect of DTT in reversing eNOS glutathionylation in aortae, DTT was added to the bioassay blood vessels, taking care to employ exactly the same conditions with the same duration of incubation and concentration of DTT as in the experiments measuring endothelial function. We then washed out the DTT and immunoprecipitated eNOS from the vessel homogenates.

For the BCNU studies, male Sprague–Dawley rats (Harlan) were used. Male SHR and WKY rats were supplied by Harlan or Charles River.

NOS3 gene silencing in bovine aortic endothelial cells

NOS3 gene silencing from BAECs was used to confirm eNOS S-glutathionylation induced by BCNU contributing to increased cellular superoxide generation. The sequence of NOS3 siRNA was based on a previous study42. The sense siRNA strand of eNOS is 5′-GA GUUACAAGAUCCGCUUCTT-3′ and the antisense siRNA is 3′-TTCUCAAUGUUCUAGGCGAAG-5′. These siRNAs were custom synthesized by Invitrogen. BLOCK-iT transfection kit (Invitrogen) was used to deliver NOS3 siRNAs to BAECs. Scrambled siRNA was used as a negative control. After 48 h, eNOS immunoblotting was used to determine the eNOS knockdown efficiency. The same set of BAECs was further treated with 80 μM BCNU for 4 h, and confocal microscopy with DHE was used to determine BCNU-induced superoxide generation.

Homogenization of cells and tissues

Cells or tissues were homogenized in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 500 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM NEM, and protease inhibitors) with a tissue grinder. After homogenization, cell or tissue debris was removed by centrifugation at 4 °C for 1 h. The supernatant was further used for immunoblotting analysis or immunoprecipitation assay.

Immunoprecipitation assay

Supernatant of cell or tissue lysate was used for the immunoprecipitation assay. Agarose-conjugated anti-eNOS (Santa Cruz) antibody was first incubated overnight with cell or tissue lysate at 4 °C. After incubation, eNOS immunoprecipitation product was washed three times with cold PBS buffer. 1 × SDS loading buffer was used to elute eNOS for immunoblotting analysis of eNOS glutathionylation.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as means and s.e.m. All experiments were repeated at least three times. Microsoft Excel and Origin were used for data analysis. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis, with P < 0.05 being considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Zhang and K. Green-Church for support with mass spectrometric analysis. This work was supported by R01 grants HL63744, HL65608, HL38324 (J.L.Z.), HL83237 (Y.-R.C.) and HL103846 (C.-A.C.) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Author Contributions C.-A.C., the primary author, performed most of the experiments and data analysis with assistance from T.-Y.W., S.V. and L.J.D. L.R. and T.-Y.W. performed the vessel studies. S.V. performed the confocal microscopy and immunohistology work. C.H. performed molecular modelling and protein expression and purification. Y.-R.C. provided mass spectrometry expertise and guidance. M.A.H.T. coordinated physiology experiments and data analysis. J.L.Z. envisioned, directed, guided and fully supported all of the work and prepared the final manuscript with input from all the authors. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Author Information Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints. The authors declare no competing financial interests. Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of this article at www.nature.com/nature.

Full Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

References

- 1.Bredt DS, et al. Cloned and expressed nitric oxide synthase structurally resembles cytochrome P-450 reductase. Nature. 1991;351:714–718. doi: 10.1038/351714a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palmer RM, Ashton DS, Moncada S. Vascular endothelial cells synthesize nitric oxide from L-arginine. Nature. 1988;333:664–666. doi: 10.1038/333664a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rapoport RM, Draznin MB, Murad F. Endothelium-dependent relaxation in rat aorta may be mediated through cyclic GMP-dependent protein phosphorylation. Nature. 1983;306:174–176. doi: 10.1038/306174a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xia Y, Tsai AL, Berka V, Zweier JL. Superoxide generation from endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. A Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent and tetrahydrobiopterin regulatory process. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25804–25808. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vasquez-Vivar J, et al. Superoxide generation by endothelial nitric oxide synthase: the influence of cofactors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9220–9225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stuehr DJ, Santolini J, Wang ZQ, Wei CC, Adak S. Update on mechanism and catalytic regulation in the NO synthases. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:36167–36170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400017200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dumitrescu C, et al. Myocardial ischemia results in tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) oxidation with impaired endothelial function ameliorated by BH4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15081–15086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702986104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giustarini D, Rossi R, Milzani A, Colombo R, Dalle-Donne I. S-glutathionylation: from redox regulation of protein functions to human diseases. J Cell Mol Med. 2004;8:201–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2004.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biswas S, Chida AS, Rahman I. Redox modifications of protein-thiols: emerging roles in cell signaling. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;71:551–564. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ying J, Clavreul N, Sethuraman M, Adachi T, Cohen RA. Thiol oxidation in signaling and response to stress: detection and quantification of physiological and pathophysiological thiol modifications. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:1099–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill BG, Bhatnagar A. Role of glutathiolation in preservation, restoration and regulation of protein function. IUBMB Life. 2007;59:21–26. doi: 10.1080/15216540701196944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hofmann H, Schmidt HH. Thiol dependence of nitric oxide synthase. Biochemistry. 1995;34:13443–13452. doi: 10.1021/bi00041a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harbrecht BG, et al. Glutathione regulates nitric oxide synthase in cultured hepatocytes. Ann Surg. 1997;225:76–87. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199701000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fulton D, et al. Regulation of endothelium-derived nitric oxide production by the protein kinase Akt. Nature. 1999;399:597–601. doi: 10.1038/21218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen CA, Druhan LJ, Varadharaj S, Chen YR, Zweier JL. Phosphorylation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase regulates superoxide generation from the enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:27038–27047. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802269200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcin ED, et al. Structural basis for isozyme-specific regulation of electron transfer in nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:37918–37927. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406204200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caruso RL, Upham BL, Harris C, Trosko JE. Biphasic lindane-induced oxidation of glutathione and inhibition of gap junctions in myometrial cells. Toxicol Sci. 2005;86:417–426. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Qiao M, Mieyal JJ, Asmis LM, Asmis R. Molecular mechanism of glutathione-mediated protection from oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced cell injury in human macrophages: role of glutathione reductase and glutaredoxin. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:775–785. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J, Pan S, Berk BC. Glutaredoxin mediates Akt and eNOS activation by flow in a glutathione reductase-dependent manner. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1283–1288. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.144659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sugiyama T, Michel T. Thiol-metabolizing proteins and endothelial redox state: differential modulation of eNOS and biopterin pathways. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H194–H201. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00767.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muscoli C, et al. On the selectivity of superoxide dismutase mimetics and its importance in pharmacological studies. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;140:445–460. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang A, Xiao H, Samii JM, Vita JA, Keaney JF., Jr Contrasting effects of thiol-modulating agents on endothelial NO bioactivity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C719–C725. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.2.C719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sayed N, Baskaran P, Ma X, van den Akker F, Beuve A. Desensitization of soluble guanylyl cyclase, the NO receptor, by S-nitrosylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:12312–12317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703944104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vita JA, et al. L-2-Oxothiazolidine-4-carboxylicacidreversesendothelialdysfunction in patients with coronary artery disease. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1408–1414. doi: 10.1172/JCI1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kugiyama K, et al. Intracoronary infusion of reduced glutathione improves endothelial vasomotor response to acetylcholine in human coronary circulation. Circulation. 1998;97:2299–2301. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.23.2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xia Y, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Snyder SH, Zweier JL. Nitric oxide synthase generates superoxide and nitric oxide in arginine-depleted cells leading to peroxynitrite-mediated cellular injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6770–6774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cardounel AJ, Xia Y, Zweier JL. Endogenous methylarginines modulate superoxide as well as nitric oxide generation from neuronal nitric-oxide synthase: differences in the effects of monomethyl- and dimethylarginines in the presence and absence of tetrahydrobiopterin. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:7540–7549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410241200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Druhan LJ, et al. Regulation of eNOS-derived superoxide by endogenous methylarginines. Biochemistry. 2008;47:7256–7263. doi: 10.1021/bi702377a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pryor WA, et al. Free radical biology and medicine: it’s a gas, man! Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R491–R511. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00614.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szabo C. Hydrogen sulphide and its therapeutic potential. Nature Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:917–935. doi: 10.1038/nrd2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodriguez-Crespo I, Gerber NC, Ortiz de Montellano PR. Endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. Expression in Escherichia coli, spectroscopic characterization, and role of tetrahydrobiopterin in dimer formation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11462–11467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.19.11462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berka V, Palmer G, Chen PF, Tsai AL. Effects of various imidazole ligands on heme conformation in endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Biochemistry. 1998;37:6136–6144. doi: 10.1021/bi980133l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen CL, et al. Site-specific S-glutathiolation of mitochondrial NADH ubiquinone reductase. Biochemistry. 2007;46:5754–5765. doi: 10.1021/bi602580c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giraldez RR, Panda A, Xia Y, Sanders SP, Zweier JL. Decreased nitric-oxide synthase activity causes impaired endothelium-dependent relaxation in the postischemic heart. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21420–21426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xia Y, Cardounel AJ, Vanin AF, Zweier JL. Electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy with N-methyl-D-glucamine dithiocarbamate iron complexes distinguishes nitric oxide and nitroxyl anion in a redox-dependent manner: applications in identifying nitrogen monoxide products from nitric oxide synthase. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;29:793–797. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vanin AF, Liu X, Samouilov A, Stukan RA, Zweier JL. Redox properties of iron-dithiocarbamates and their nitrosyl derivatives: implications for their use as traps of nitric oxide in biological systems. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1474:365–377. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(00)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roubaud V, Sankarapandi S, Kuppusamy P, Tordo P, Zweier JL. Quantitative measurement of superoxide generation using the spin trap 5-(diethoxyphosphoryl)-5-methyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide. Anal Biochem. 1997;247:404–411. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen CA, Cowan JA. Characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Atm1p: functional studies of an ABC7 type transporter. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1760:1857–1865. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shaul PW, et al. Acylation targets emdothelial nitric-oxide synthase to plasmalemmal caveolae. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6518–6522. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takizawa T, Robinson JM. Ultrathin cryosections: an important tool for immunofluorescence and correlative microscopy. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51:707–714. doi: 10.1177/002215540305100602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alzawahra WF, Talukder MA, Liu X, Samouilov A, Zweier JL. Heme proteins mediate the conversion of nitrite to nitric oxide in the vascular wall. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H499–H508. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00374.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kang-Decker N, et al. Nitric oxide promotes endothelial cell survival signaling through S-nitrosylation and activation of dynamin-2. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:492–501. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.