Abstract

Thermococcus kodakarensis (T. kodakarensis) has emerged as a premier model system for studies of archaeal biochemistry, genetics, and hyperthermophily. This prominence is derived largely from the natural competence of T. kodakarensis and the comprehensive, rapid, and facile techniques available for manipulation of the T. kodakarensis genome. These genetic capacities are complemented by robust planktonic growth, simple selections, and screens, defined in vitro transcription and translation systems, replicative expression plasmids, in vivo reporter constructs, and an ever-expanding knowledge of the regulatory mechanisms underlying T. kodakarensis metabolism. Here we review the existing techniques for genetic and biochemical manipulation of T. kodakarensis. We also introduce a universal platform to generate the first comprehensive deletion and epitope/affinity tagged archaeal strain libraries.

Keywords: genetics, recombination, hyperthermophilic, archaea, Thermococcales, transcription

Introduction

Archaea are prevalent in many extreme environments but are also found in vast numbers in mesophilic marine and terrestrial environments where they contribute substantially to carbon, phosphorous, sulfur, and nitrogen cycles (Jarrell et al., 2011, references cited therein). Their importance in these global cycles is newly appreciated and demands a more complete understanding of archaeal encoded biochemistries and metabolic pathways. Advances have been limited due in large part to the difficulties associated with cultivating many archaea in the laboratory and the severe bottleneck resultant from the lack of genetic systems for most archaea. The dearth of genetic resources not only restricts our understanding of archaea in their natural environments, but also constrains the utility of this Domain for biomedical, biochemical, and industrial applications. This knowledge gap is perhaps most poignant for the hyperthermophilic archaea wherein the commercial utility of thermostable enzymes has been long recognized (Fujiwara et al., 1998; Hashimoto et al., 2001; Imanaka et al., 2001; Izumi et al., 2001; Hotta et al., 2002; Imanaka and Atomi, 2002; Cho et al., 2007; Griffiths et al., 2007; Blumer-Schuette et al., 2008; De Stefano et al., 2008; Bae et al., 2009; Kelly et al., 2009; Gaidamaviciute et al., 2010).

Within just the past decade, the recalcitrance of the archaea has dramatically declined due to advances in genetic techniques for select model organisms, and our understanding of archaeal physiology has resultantly exponentially increased (Tumbula and Whitman, 1999; Rother and Metcalf, 2005; Albers and Driessen, 2008; Santangelo et al., 2010; Leigh et al., 2011; Lipscomb et al., 2011). Essentially all barriers have been removed, and arguably the most complete set of genetic techniques has been developed for the globally abundant Thermococcales (Endoh et al., 2008; Santangelo and Reeve, 2010b; Bridger et al., 2011; Farkas et al., 2011; Takemasa et al., 2011). The model organism Thermococcus kodakarensis (T. kodakarensis; formally Pyrococcus kodakaraensis or T. kodakaraensis; Morikawa et al., 1994; Atomi et al., 2004b), for which the most complete suite of genetic techniques is available, is the subject of this review.

New avenues, based on advances in T. kodakarensis genetics, permit direct characterization of innumerable archaeal enzymes and their chemistries (Atomi et al., 2001, 2004a; Shiraki et al., 2003; Fukuda et al., 2004, 2008; Rashid et al., 2004; Sato et al., 2004, 2007; Imanaka et al., 2006; Murakami et al., 2006; Orita et al., 2006; Kanai et al., 2007, 2010, 2011; Danno et al., 2008; Fujiwara et al., 2008; Louvel et al., 2009; Yokooji et al., 2009; Borges et al., 2010; Kobori et al., 2010; Morimoto et al., 2010; Matsubara et al., 2011), provide industrially relevant alternative biofuel platforms(Kanai et al., 2005, 2011; Chou et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2010; Atomi et al., 2011; Santangelo et al., 2011; Bae et al., 2012; Davidova et al., 2012), unlock the largely untapped reservoir of archaeal encoded natural products (Atomi, 2005; Kim and Peeples, 2006; Littlechild, 2011; Matsumi et al., 2011; Sato and Atomi, 2011), and offer the opportunity to dissect eukaryotic-like information processing systems composed of minimal components (Yamamoto et al., 2003; Santangelo and Reeve, 2006, 2010a; Kanai et al., 2007; Santangelo et al., 2007, 2008a, 2009; Hirata et al., 2008; Dev et al., 2009; Yamaji et al., 2009; Fujikane et al., 2010; Li et al., 2010, 2011; Ishino et al., 2011; Nunoura et al., 2011; Pan et al., 2011; Santangelo and Artsimovitch, 2011).

Thermococcus kodakarensis is a marine, anaerobic, heterotrophic, hyperthermophilic (85°C), planktonic euryarchaeon, and thrives in medium supplemented with peptides, starch, or chitin, using S° or H+ as a terminal electron acceptor, generating H2S or H2, respectively. T. kodakarensis grows rapidly (doubling rate ∼40 min in rich media) to high cell densities and produces defined colonies on solid media, allowing overnight selections reliant on prototrophic markers (i.e., tryptophan, arginine, uracil, or agmatine) or antibiotic resistance (i.e., mevinolin, simvastatin) on defined or rich plates. Counter-selective procedures have been developed that facilitate repetitive modification of T. kodakarensis’ small 2.08 Mb genome (52% GC; Fukui et al., 2005) that readily incorporates exogenous DNA via homologous recombination with high efficiency (Sato et al., 2003). T. kodakarensis is naturally competent, requires no special techniques for transformation, accepts linear and circular DNAs, and via homologous recombination through short sequences of complementarity yields transformants at a frequency of ∼1 in 107 cells plated (∼100 transformants/109 cells/μg of transforming DNA). T. kodakarensis can support maintenance of autonomously replicating plasmids that provide ectopic expression platforms (Santangelo et al., 2008b), and a strong knowledge base of transcription regulation allows selective expression of native or introduced genes.

This multitude of selective markers and genetic techniques allow for essentially limitless genomic alterations including gene deletion, gene insertion, gene modification (allelic modifications as well as addition of affinity and epitope tags), promoter exchange, reporter gene expression, and any combination therein. Simple preservation techniques permit long-term frozen strain storage and the pace of strain construction is now limited only by molecular biology considerations. Here we briefly review existing genetic techniques available for T. kodakarensis and present a universally applicable platform and strategy developed to generate the first comprehensive archaeal strain collections.

Genetic Techniques Allowing Modification of the T. kodakarensis Genome

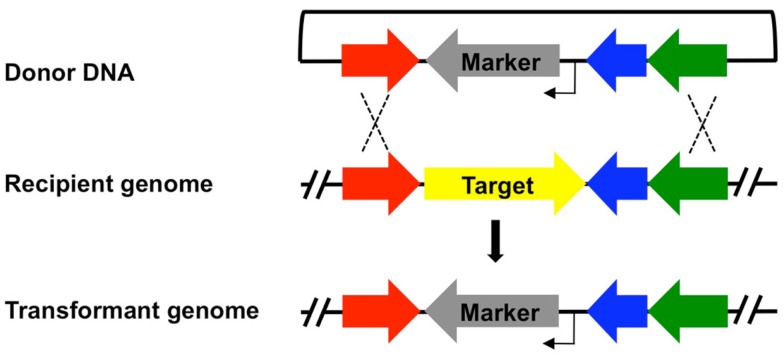

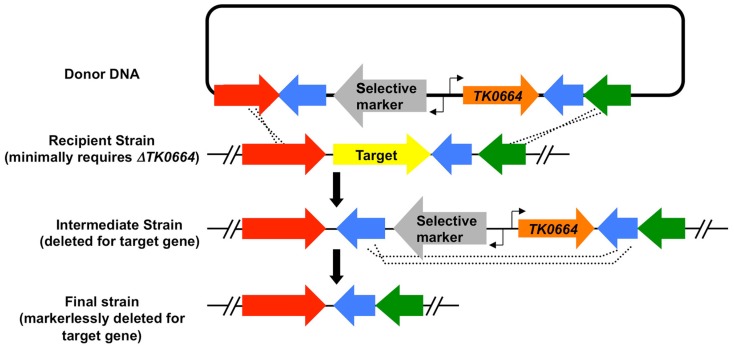

Protocols for T. kodakarensis growth and genetic manipulation, as well as the underlying basis of each selection have recently been reviewed (Santangelo and Reeve, 2010b) and here we instead focus on the advantages and limitations of each technique and selective system. Table 1 provides an overview of the genetic selections available and highlights the utility and limitations of each system. Each selective marker can be deployed as a single expression cassette, allowing the marker to be incorporated into and retained within the genome while coincidently modifying the genome in some manner, for example to generate a strain deleted for a specific gene (Figure 1). With the exception of the uracil-based marker (see below), use of any marker in isolation necessarily eliminates reuse of the same marker for any subsequent modification of the same genome. Individual markers have been employed consecutively to produce strains with multiple modifications, with each modification resulting in an additional marker retained in the genome of the final strain. More often, counter-selective pressures applied to recover the marker through a recombination based excision from the genome, allowing for markerless and repetitive modifications to be made to a single genome. Such counter-selective strategies are available for the uracil and 6-methyl purine (6MP) based markers, but only the uracil marker is functional for both positive- and counter-selection in isolation. The 6MP-based marker provides no useful positive selection, but can be paired with any of the positive selection cassettes to provide a two-gene cassette capable of positive selection into and counter-selective excision from the T. kodakarensis genome (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Selective markers available for modification of Thermococcus kodakarensis.

| Selectable marker | Gene(s) | Gene function | Strain (required genotype) | Advantages | Limitations/disadvantages | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uracil | TK2276 | Orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase | KU216 (ΔpyrF), KUW1 (ΔpyrF, ΔtrpE) | Easily paired with 5-FOA-based counter-selection for markerless modifications | Uracil contamination yields high backgrounds; limited to minimal media; limited host range | Sato et al. (2003, 2005) |

| Tryptophan | TK0254 | Large subunit of anthranilate synthase | KW128 (ΔpyrF; ΔtrpE::pyrF) | Rigid selection requiring no media additions | Limited to minimal media; limited host range | Sato et al. (2005) |

| Arginine/citrulline | PF0207, PF0208 | Argininosuccinate synthase, argininosuccinate lyase | Any strain | No strain restrictions | Limited to minimal media; requires supplementation with citrulline | Santangelo and Reeve (2010b) |

| Agmatine | TK0149 | Pyruvoyl-dependent arginine decarboxylase | TS559 (ΔpyrF; ΔtrpE::pyrF, ΔTK0664, ΔTK0149) | Provides selective pressure in rich media | Limited host range | Santangelo and Reeve (2010b) |

| Simvastatin/mevinolin | PF1848 | HMG-CoA reductase | Any strain | Provides selective pressure in rich media; no strain restrictions | Spontaneous Sim/Mev resistance provides a high background | Matsumi et al. (2007), Santangelo et al. (2007) |

| 6-methyl purine | TK0664 | Hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl-transferase | TS517 (ΔpyrF; ΔtrpE::pyrF, ΔTK0664) | Provides counter-selective pressure | Provides no positive selection; counter-selection requires minimal media | Santangelo et al. (2011) |

Figure 1.

Integration of a selection cassette into the Thermococcus kodakarensis genome provides a mechanism for genomic modification. A general scheme for integration of a selectable marker cassette (gene providing positive selection, gray; promoter, bent arrow) into the genome of a recipient strain. The resultant genome of the transformant results from two homologous recombination events (dashed lines) between flanking regions contained in both the donor DNA and targeted genomic locus. For simplicity, a single gene replacement of a target locus (yellow) by the selectable marker is shown, although different genomic alterations including allelic exchanges, promoter alterations, and additions of epitopes can similarly be introduced using the same technique. Each marker in Table 1, with the exception of 6MP, can be employed to generate strains that retain the marker at or near the modified locus.

Figure 2.

Markerless-modification of the Thermococcus kodakarensis genome via sequential positive selection and subsequent counter-selection. Donor DNA, a hypothetical target locus in the recipient genome, the resultant intermediate, and final genomes are shown. The scheme diagrammed generates an intermediate strain wherein both the selectable (gray) and counter-selectable marker (TK0664; orange) are flanked by a direct repeat (cyan), and the intermediate strain is deleted for the target gene. Alternative donor DNAs can result in intermediate strains that retain the target gene, necessitating excision of the selectable markers in addition to the target gene to via recombination between direct repeats to generate the desired final markerless-deletion strain. The same protocol can be used with the uracil (pyrF) cassette that will serve as both the positive and counter-selective marker. Any combination of a positive selection cassette (Table 1) and TK0664-based 6MP counter-selection can be employed in a two-gene mechanism to introduce markerless modifications to the T. kodakarensis genome.

Regardless of the modification, all genetic manipulations are directed to specific loci through homology between the donor DNA and the T. kodakarensis chromosome, and recombination is efficient with ∼200 or more base pairs (bp) of sequence homology (Figures 1 and 2). Smaller regions of complementarity are also functional, but constraints of this manner are atypical of most transformations. Donor DNAs are most commonly circular DNAs that cannot autonomously replicate in T. kodakarensis, although linear DNA is also suitable for transformation. Expression cassettes containing a single selectable marker are most commonly flanked by sequences with homology to the locus of choice and transformants resultant from double-homologous recombination into the T. kodakarensis genome are identified via diagnostic PCRs. Recombination of an entire circular donor DNA molecule into the genome via only a single homologous crossover does result in transformants that survive selective pressures, but under most circumstances such transformants are non-desirable and easily identified via diagnostic PCRs.

Prototrophic Selections

Arginine/citrulline-based selection

In contrast to several members of the Thermococcales, T. kodakarensis is an arginine auxotroph (Fukui et al., 2005). Introduction and expression of two genes from P. furiosus, PF0207 and PF0208 that encode argininosuccinate synthase and argininosuccinate lyase respectively, to the T. kodakarensis genome, or on a replicative plasmid (see below), were shown to provide any T. kodakarensis strain the capacity to combine citrulline and aspartate to form arginine, and thus provide arginine prototrophy. T. kodakarensis makes abundant aspartate, but cultures must be supplemented with citrulline for introduction of the exogenous P. furiosus genes to confer arginine prototrophy; citrulline supplementation in the absence of PF0207/PF0208 expression is insufficient to impart arginine prototrophy.

Arginine/citrulline-based selections are rigid, with no spontaneous arginine-prototrophic colony formation. Initial selection is limited to growth on minimal media (19 amino acids plus citrulline), but once confirmed, strains can be passage and plated on rich media without concern for retention of the marker; spontaneous excision has not been reported for any marker employed for T. kodakarensis genetic manipulations. The greatest advantage of arginine/citrulline-based selections is the lack of any genotypic strain requirements. This flexibility is unmatched by the other available prototrophic markers, and although the arginine/citrulline-based selection has only recently been developed, it is compatible with all other selections. The only potential disadvantage is the necessity to supplement defined media with citrulline, however addition is not of significant concern based on cost, availability, or stability, nor is addition of citrulline necessary for growth in rich media.

Tryptophan-based selection

Only specific strains of T. kodakarensis are amenable to tryptophan-based selection, although these strains are widely available and selections based on tryptophan have been employed in the most diverse T. kodakarensis strain constructions (Sato et al., 2003, 2005; Imanaka et al., 2006). Most reported tryptophan auxotrophic strains are non-reverting as the result of an insertion in TK0254 (trpE), encoding the large subunit of anthranilate synthase. Tryptophan selection, like arginine/citrulline-based selections is rigid, and no spontaneous tryptophan-prototrophic colonies have been recovered in the absence of donor DNA. Initial selections are still limited to defined media, but in contrast to arginine/citrulline-based selections, the tryptophan-based selection does not require medium supplementation. Integration of the trpE cassette is similarly stable and does not require selective pressure once established, allowing growth of confirmed strains in rich media without concern for loss of the marker.

Agmatine-based selection

Polyamines serve as essential counter-ions in all Domains and are typically derived from the precursor agmatine (Morimoto et al., 2010). Agmatine is decarboxylated arginine, and although T. kodakarensis is an arginine auxotroph, it does encode a pyruvoyl-dependent arginine decarboxylase (TK0149; Fukuda et al., 2008). Deletion or inactivation of TK0149 results in the agmatine-dependent growth, allowing selections in specific strains wherein TK0149 was previously deleted (Santangelo and Reeve, 2010b). The major advantage of agmatine-based selections, despite their limited host range, is that agmatine auxotrophy is lethal even in rich media, thus initial selections to agmatine prototrophy can be performed on rich media. This pronounced difference from uracil-, arginine/citrulline-, or tryptophan-based prototrophic selections provides a means for selection of transformants overnight in contrast to the 3–4 days typically required for colony formation on defined media.

Agmatine-based selections are as rigid as those for tryptophan or arginine/citrulline, but do require strains deleted for TK0149 as well as supplementation of these strains with agmatine prior to transformation. These concerns are minor as agmatine is inexpensive and widely available. The selective pressure provided by the agmatine-marker is particularly useful for retention of replicative plasmids in rich media (see below).

Uracil-based selection and 5-FOA-based counter-selection

The first reported selections (Sato et al., 2003, 2005) that were established into useful genetic techniques were based on spontaneous resistance to 5-fluoro-orotic acid (5-FOAR), a cytotoxic pyrimidine analog. 5-FOAR strains were isolated and shown to contain mutations disrupting the sequence of, or limiting the expression of TK2138 or TK2276 (pyrE or pyrF, respectively), consistent with the conserved roles of pyrE and pyrF in pyrimidine metabolism (Sato et al., 2003). Strains containing non-reverting mutations of pyrF serve as the host for donor DNAs that introduce targeted gene disruptions at remote loci while restoring pyrF expression, and thus uracil prototrophy, from this same location.

Uracil-dependent techniques are limited to defined media, and while uracil auxotrophy/prototrophy is still used to isolate transformants, many media components contain trace or greater amounts of uracil that routinely complicate isolation of mutants using this method. The technology is retained in large part due to its simplicity, and perhaps more importantly, the ability to counter-select against pyrF function, allowing repetitive manipulation of the genome via an initial selection and sequent counter-selection (pop-in/pop-out) mechanism (Figure 2). By integrating a pyrF cassette while at the same time introducing duplicate sequences flanking pyrF, researchers can develop so-called intermediate strains with the desired phenotype. Exposure of this intermediate strain to 5-FOA most commonly results in 5-FOAR colonies resultant from recombination between the direct repeats flanking pyrF, and thus excision of the marker from the chromosome while the desired modification is retained in the genome. The excision event produces restored uracil auxotrophy, allowing reuse of the uracil marker to generate a second, third, fourth, etc., genomic alteration. Proper planning allows for exquisite precision during initial integration and subsequent excision, permitting markerless deletions, or alternative genomic modifications.

Antibiotic-Based Selections

Few antibiotics/antimicrobials have demonstrated efficacy against archaea, and of those, only a few are stable enough at high temperature to be employed for use with hyperthermophiles. Antibiotic selections remain highly desirable as they are typically robust, effective on many media, and provide continued selective pressure when transformants are transferred to liquid media. A class of statins, developed to inhibit cholesterol biosynthesis and typified by simvastatin (Sim) and mevinolin (Mev), is effective in the low μM range at limiting T. kodakarensis growth (Matsumi et al., 2007; Santangelo et al., 2008a). Archaeal strains spontaneously resistant to Sim/Mev (Sim/MevR) were shown to have mutations that mapped to the locus encoding 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMG-CoA reductase), and these mutations generally lead to overexpression of HMG-CoA reductase (Lam and Doolittle, 1992). It was hypothesized and subsequently shown that increased expression of, rather than modifications to, HMG-CoA reductase provided a level of resistance to Sim/Mev. Selections based on the introduction of an additional and highly expressed copy of HMG-CoA reductase, provided to generally increase the in vivo levels of HMG-CoA reductase soon followed, with the HMG-CoA reductase from P. furiosus employed to limit unwanted recombination between the native T. kodakarensis HMG-CoA reductase and the introduced copy of HMG-CoA reductase.

Selections based on Sim/MevR are advantageous in that they are not limited to a select genotype and provide selective pressure in all media allowing rapid selection on rich media. However, Sim/Mev-based selections are disreputably weak and are cost prohibitive on a large scale. Spontaneous Sim/MevR colonies are readily recovered, and this incidence presents real and significant challenges when working with slow growing strains that may be overwhelmed in liquid culture by spontaneous Sim/MevR cells. Plasmid maintenance based on Sim/MevR is possible, with the noted caveats of spontaneous resistance.

Two-Gene Selection/Counter-Selection Modification of the T. kodakarensis Chromosome

The uracil-based selection and 5-FOA-based counter-selection are advantageous for generating strains with markerless modifications to the T. kodakarensis chromosome and for repeated manipulation of the same chromosome at multiple loci, but is hamstrung by the lack of rigidity in generating uracil free media. The uracil contamination of most commercially available medium components is sufficient to support weak growth of ΔpyrF strains over the course of several days.

To circumvent these concerns, a more rigid selection/counter-selection procedure was developed based on the sensitivity of all T. kodakarensis strains to the cytotoxic compound 6-methyl purine (6MP). T. kodakarensis encodes a complete purine biosynthetic pathway, but like many organisms also encodes a purine-scavenging pathway to recycle purines and nucleotides from the environment. 6MP is a nucleotide base analog that, once imported and converted to a modified nucleotide- or deoxynucleotide-triphosphate and incorporated into macromolecules, overwhelms DNA repair pathways and inhibits the information processing machinery. Spontaneous 6MPR T. kodakarensis strains were isolated, and the mutations resulting in 6MPR were mapped. All mutations were at the TK0664 locus, and it was subsequently shown that inactivation or deletion of TK0664, encoding a hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyltransferase, conferred 6MPR.

A 6MP-based counter-selection against TK0664 was established, but required pairing with an initial prototrophic or antibiotic-based positive selection to generate initial transformants. Combining any of the selection cassettes with a cassette encoding TK0664 provides a two-gene based selection/counter-selection procedure (Figure 2) that functionally mimics the single pyrF-based uracil prototrophy selection, 5-FOA counter-selection protocol. The limitations of this two-gene system include the necessity to introduce two expression cassettes during initial strain construction, the reasonable expense of 6MP, the very limited host range, and the requirement of a different host strain for each gene pair. These complications are largely outweighed by the efficiency of the system compared to the uracil-based selection/counter-selection, but are still laborious.

Replicative Expression Vectors

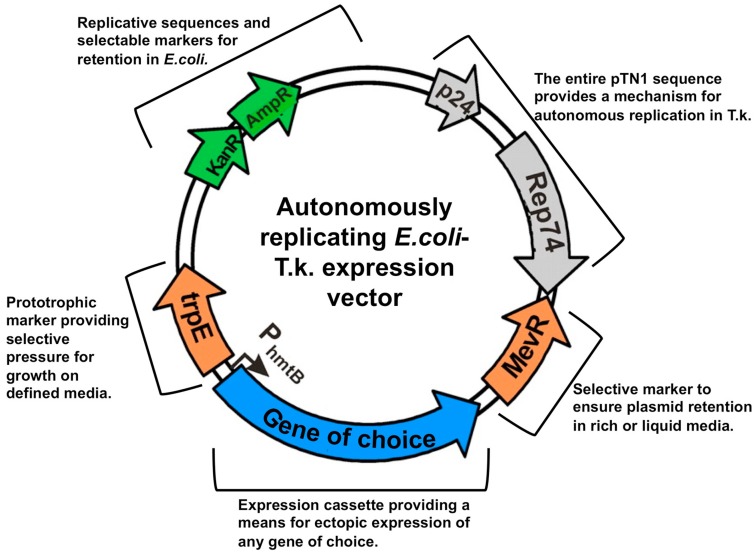

Thermococcus kodakarensis does not naturally contain any extrachromosomal elements, but T. kodakarensis does support replication of plasmids derived from other Thermococcales. T. nautilus was shown to contain three distinct plasmids (Soler et al., 2007), and the smallest of these, pTN1, was converted into an E. coli-T. kodakarensis shuttle vector (Figure 3; Santangelo et al., 2008b). Variants of this vector carrying most combinations of selective markers are available, and necessarily retain at least one marker (Sim/Mev or agmatine) that exerts selective pressure in rich media.

Figure 3.

Replicative vectors provide platforms for exogenous and ectopic expression in Thermococcus kodakarensis. T.k-E. coli shuttle vectors are the result of merging the entire Thermococcus nautilus-derived pTN1 sequence with a common E. coli plasmid (pCR2.1-Topo; Invitrogen). The marker additions provide the means to select T. kodakarensis transformants on any media, and the expression cassette provides a mechanism to ectopically express any gene of choice in T. kodakarensis.

When these vectors are used to express essential genes, the chromosomal locus for the same gene can be modified or deleted, and viability may then be dependent on retention of the plasmid. Replicative vectors also permit protein expression under native conditions, at controlled levels, and allow T. kodakarensis to serve as a host of exogenous gene expression (Santangelo et al., 2008b, 2010; Takemasa et al., 2011). The latter may impart novel capacities to T. kodakarensis, or fulfill industrial needs for thermostable protein expression. These shuttle vectors can be easily modified in E. coli to introduce sequences encoding epitopes and affinity tags that facilitate downstream purification of the encoded products. Finally, collections of plasmids, for example, a plasmid library containing randomly mutagenized variants of a gene, can be quickly produced in E. coli and the efficiency of T. kodakarensis transformation supports introduction of this library for use in screens and selections.

A Universal Platform for Construction of Comprehensive Strain Collections

The existing genetic techniques for T. kodakarensis were recently combined into a universally applicable strategy to generate the first comprehensive strain libraries for any archaeon. Two T. kodakarensis strain libraries, one wherein each non-essential gene is individually deleted, and a second wherein each protein-encoding gene is modified to encode an epitope and affinity tagged isoform, are under construction. We outline some details of the streamlined procedure for construction of the library vectors and associated strains (Figures 4–6). This platform can be adapted to generate any T. kodakarensis strain of choice and provides an alternative to the often laborious molecular biology manipulations that are required to generate standard vectors for integration into, and subsequent excision from, the T. kodakarensis genome. The use of single crossover integrations provides for the possibility of excision of the plasmid to restore the TS559 genome without modification, as would be necessary when targeting an essential gene. Continued recovery of only the restored TS559 genome provides a statistical measure that can be applied to determine essentiality of individual genes.

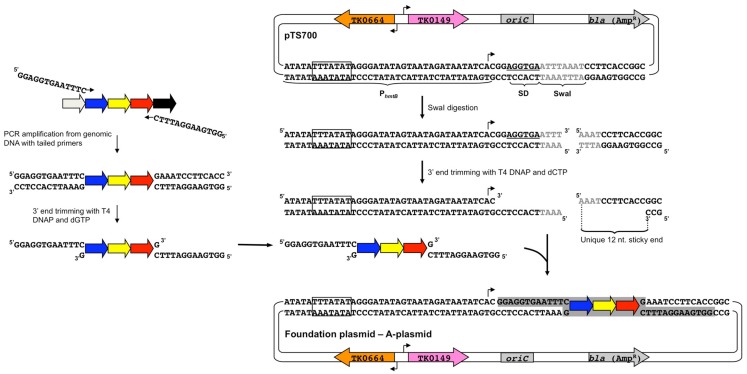

Figure 4.

Construction of foundation plasmids by a ligation-independent technique. (Left) Each target gene as well as ∼500–700 bp of both upstream and downstream adjacent DNA is amplified from T. kodakarensis chromosomal DNA with a pair of primers that introduce unique 13 bp terminal extensions to the amplicon. Incubation of the purified amplicon with T4 DNA polymerase (DNAP) and only dGTP leads to a 3′-5′ exonuclease recession of the 3′ ends to produce non-complementary 12-nt sticky ends. (Right) pTS700 is linearized through a unique SwaI site, producing 3′ ends that are similarly recessed with T4 DNAP and dCTP to yield sticky ends complementary to the sticky ends of each amplicon permitting directional cloning of the amplicon in a ligase-independent reaction. Amplicons for each T. kodakarensis gene, regardless of gene orientation, gene length, or sequence can be cloned in an identical manner to yield foundation plasmids (A-plasmids). The TATA-box of PhmtB is boxed and the site of transcription initiation marked with a bent arrow; the Shine–Dalgarno sequence (SD) is underlined; the SwaI recognition sequence is shown in gray; the selectable and counter-selectable expression cassettes, TK0149 and TK0664, are shown in pink and orange, respectively; the plasmid origin of replication (oriC) and E. coli resistance cassette (bla) are shown in gray. The color scheme is conserved in Figures 4–7.

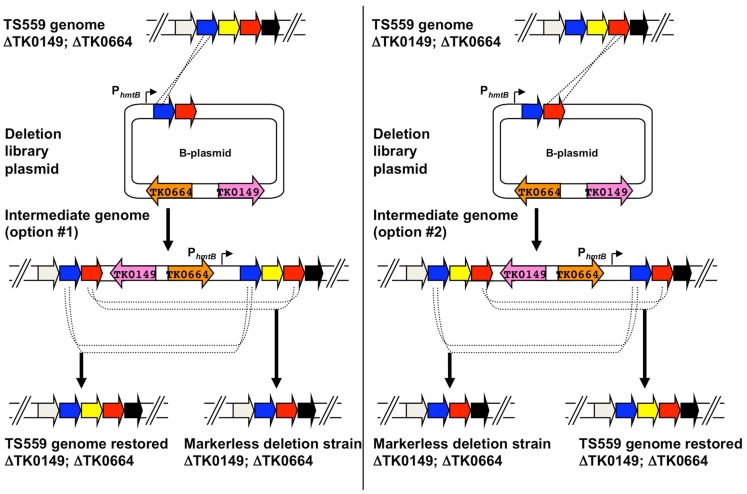

Figure 6.

Use of deletion plasmids (B-plasmids) to generate markerless knockouts in the genome of Thermococcus kodakarensis. A hypothetical region of the genome of T. kodakarensis strain TS559 is shown at top, with the left and right panels depicting the two possible integration events yielding agmatine-prototrophic intermediate strains from the diagramed B-plasmid. Both intermediate strains #1 and #2 contain direct repeats flanking the target locus, and dependent on recombination responsible for excision upon counter-selection with 6MP, either the original TS559 genome can be restored or the desired deletion genome generated.

The collections are all based on a single T. kodakarensis strain and vector, but the technologies employed are nearly identical to the platforms described above. pTS700 provides the vehicle for introduction of donor DNA complementary to the T. kodakarensis genome and carries the selectable and counter-selectable markers facilitating the most rapid and rigid integration into and excision from the T. kodakarensis genome, but will not autonomously replicate in T. kodakarensis (Figure 4). The host strain, TS559, has the complementary genotype (ΔpyrF; ΔtrpE::pyrF, ΔTK0664, ΔTK0149) for the selectable markers carried on pTS700. The strain libraries so constructed are markerless, and as such the resultant strains are isogenic while importantly permitting continued modification of the strains using the library of vectors so established. The strains are compatible with every replicative vector, further increasing their utility for complex genetic manipulations and their use in selections and screens to isolate strain variants of choice. The use of a single platform provides for economical and rapid construction of the necessary vectors to generate ∼4,600 unique strains.

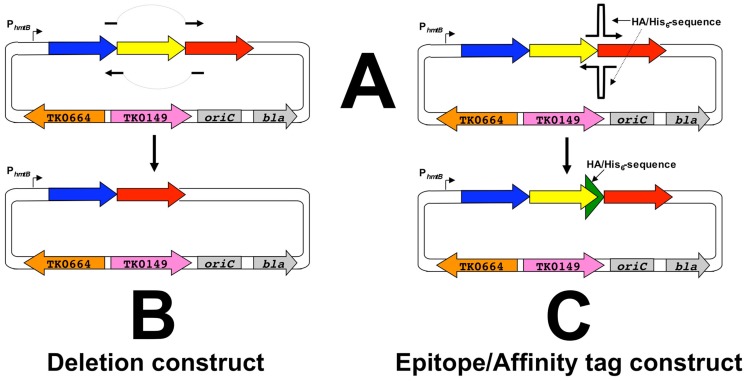

Construction begins with amplification of a target gene (shown in yellow, Figure 4) with ∼500–700 bp of flanking DNA. This amplicon is cloned via a ligation-independent mechanism into pTS700 generating the initial vector termed an “A” plasmid. The ligation-independent mechanism permits all amplicons to be cloned using the same procedure, thus simplifying construction of ∼2,300 A-plasmids, one for each T. kodakarensis protein-encoding gene. Each A-plasmid serves as a foundation plasmid, from which additional vectors of choice can be generated. Two plasmid variants, termed “B-” and “C-plasmids,” are typically generated from the A-plasmid that respectively provide the donor DNAs to generate the deletion and epitope/affinity tagged T. kodakarensis strains for each protein-encoding gene. A-plasmids can undergo additional or combinatorial modifications for construction of more unique strains (i.e., “Q-plasmids” contain modified promoters; “M-plasmids” contain allelic modifications), but for this review we concentrate on construction of the deletion and epitope/affinity tagged libraries.

B-plasmids are constructed in a single-step PCR-based procedure wherein the original target gene (yellow) is deleted from the plasmid, while leaving the flanking DNA that will target integration of the entire B-plasmid to the TS559 genome (Figure 5). Two separate initial integration events are possible for incorporation of the entire B-plasmid to the genome, and each generates an intermediate strain that, when 6MP-based counter-selective pressure is applied, can undergo an internal recombination event to either restore the original genome or produce a strain containing a genome with the desired, targeted deletion (Figure 6). The ratio of WT versus desired deletion recovered 6MPR strains provides a statistical measure identifying essential genes; failure to recover a strain with the desired deletion from a large number of 6MPR final strains implies essentiality.

Figure 5.

Construction of deletion- and affinity-plasmids from the foundation plasmids. A-plasmids serve as templates for PCR (QuikChange; Agilent) wherein essentially the entire plasmid is replicated to generate B,C-plasmids respectively. B-plasmids result from primer pairs that are complementary, both upstream and downstream, of the target gene (yellow), whereas C-plasmids result from primer pairs that introduce 45 additional nucleotides, encoding both a His6 and HA epitope tag, in-frame and immediately prior to the normal stop codon of the target gene. A simplified diagram of the plasmids is used for clarity only and each plasmid retains all the components highlighted in Figure 4. The larger green arrow depicts the sequence encoding the His6-HA tag.

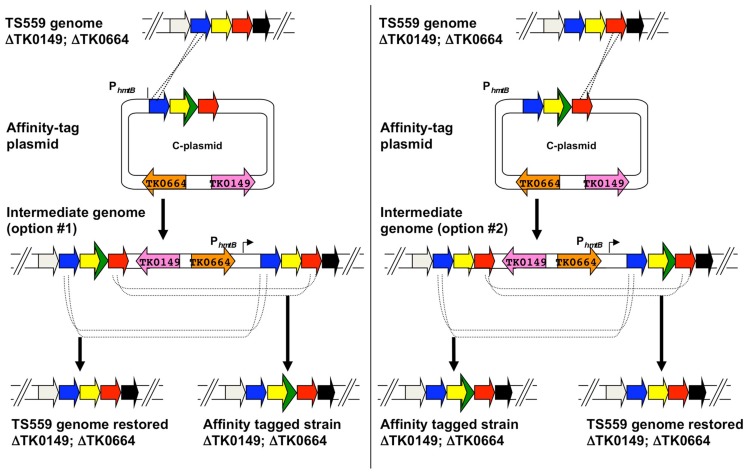

C-plasmids are similar constructed from A-plasmids via a PCR-based procedure that introduces the 45 bp encoding the His6 and 9-amino acid hemagglutinin (HA; YPYDVPDYA) tag to the target gene, whilst retaining the entire original amplicon of the foundation plasmid (Figures 5 and 7). Both the His6 and HA-tags have been used successful to facilitate protein identification and ease protein purification with minimal background. C-plasmids can similarly integrate and excise from the genome to generate the desired tagged strain or restore the TS559 genome.

Figure 7.

Use of epitope/affinity tag plasmids (C-plasmids) to generate markerlessly tagged-strains of Thermococcus kodakarensis. A hypothetical region of the genome of T. kodakarensis strain TS559 is shown at top, with the left and right panels depicting the two possible integration events yielding agmatine-prototrophic intermediate strains from the diagramed C-plasmid. Both intermediate strains #1 and #2 contain direct repeats flanking the target locus, and dependent on recombination responsible for excision upon counter-selection with 6MP, either the original TS559 genome can be restored or the desired tag- and epitope-containing genome generated.

The donor plasmids also contain the constitutively expressed PhmtB promoter immediately upstream of the site wherein the initial amplicon is cloned to generate the A-plasmid. PhmtB provides an expression platform for genes that may become separated from their promoter, as would be common for an integration event that disrupts an operon.

Conclusion

The genetic techniques and tools for T. kodakarensis provide a potent arsenal of mechanisms to precisely and repetitively modify the chromosome, as well as ectopically introduce and express exogenous or modified genes in vivo. The selectable markers and host strains developed to date provide the means for essentially any modification in any strain background. Although not the subject of this review, the developed reporter constructs (Santangelo et al., 2008a, 2010) and in vitro transcription (Santangelo et al., 2007) and translation systems (Endoh et al., 2006, 2007; Yamaji et al., 2009) using T. kodakarensis components provide complementary in vivo and in vitro platforms to dissect regulation of transcription and translation regulatory mechanisms.

The possibility of generating comprehensive strain libraries is now a reality, and a common platform is in place to speed construction of such libraries and provide the community the first comprehensive strain collections with the most isogenic background possible. Furthering their value, the plasmid and strain libraries so constructed retain value for additional strain modification, including strains containing multiple deletions or multiple genes with tagged isoforms. More specific and imaginative variants are quickly feasible through minor modification of the foundation plasmids for each protein-encoding gene; for example, strains with promoter alterations and allelic modifications can now be combined with select deletions, and these modifications can be made in backgrounds wherein other protein-encoding genes are tagged or modified. This depth of genetic flexibility will permit entire pathways to be introduced into, or deleted from, the T. kodakarensis genome, and provides a mechanism to probe biochemical pathways using complementation and screens and selections to isolate mutants with desired phenotypes.

The toolkit for T. kodakarensis genetics is impressive, but still incomplete. Specifically, transduction would further speed strain construction, but is not yet possible. The isolation of the first virus capable of replication in T. kodakarensis (Gorlas et al., 2012) may facilitate development of a transduction method. Replicative expression vectors currently all share the same origin (pTN1-based; Soler et al., 2007), and the development of additional shuttle vectors with complementary origins of replication derived from plasmids newly identified in Thermococcal species (Gonnet et al., 2011; Soler et al., 2011) would permit addition of several plasmids to the cell at once, or allow plasmid shuffle experiments as may be required when analyzing the function of essential genes. Constructs and promoters allowing easily regulated in vivo expression would be a welcome addition, providing a simply mechanism to turn gene expression off and on to monitor the effects of loss or gain of function on phenotype under dynamic conditions. Transformation efficiency should be improved, and insights may be garnered from the recently developed genetic system for the closely related organism P. furiosus wherein transformation efficiency is several orders of magnitude greater than that of T. kodakarensis (Lipscomb et al., 2011). These endeavors, as well as the ability to currently probe the form and function of each T. kodakarensis encoded gene, will undoubtedly continue to add to our knowledge and understanding of archaeal physiology, provide the basis for new technologies and production of commercial-relevant products, and underlie the basic research exploiting the component-simplified information processing machinery shared by archaea and eukaryotes.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by grants GM098176 and GM100329 from the National Institutes of Health to T.J.S.

References

- Albers S. V., Driessen A. J. (2008). Conditions for gene disruption by homologous recombination of exogenous DNA into the Sulfolobus solfataricus genome. Archaea 2, 145–149 10.1155/2008/948014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atomi H. (2005). Recent progress towards the application of hyperthermophiles and their enzymes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 9, 166–173 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atomi H., Ezaki S., Imanaka T. (2001). Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase from Thermococcus kodakarensis KOD1. Meth. Enzymol. 331, 353–365 10.1016/S0076-6879(01)31070-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atomi H., Matsumi R., Imanaka T. (2004a). Reverse gyrase is not a prerequisite for hyperthermophilic life. J. Bacteriol. 186, 4829–4833 10.1128/JB.186.14.4829-4833.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atomi H., Fukui T., Kanai T., Morikawa M., Imanaka T. (2004b). Description of Thermococcus kodakarensis sp nov, a well studied hyperthermophilic archaeon previously reported as Pyrococcus sp KOD1. Archaea 1, 263–267 10.1155/2004/204953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atomi H., Sato T., Kanai T. (2011). Application of hyperthermophiles and their enzymes. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 22, 618–626 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae H., Kim K. P., Lee J. I., Song J. G., Kil E. J., Kim J. S., Kwon S. T. (2009). Characterization of DNA polymerase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus marinus and its application to PCR. Extremophiles 13, 657–667 10.1007/s00792-009-0248-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae S. S., Kim T. W., Lee H. S., Kwon K. K., Kim Y. J., Kim M. S., Lee J. H., Kang S. G. (2012). H2 production from CO, formate or starch using the hyperthermophilic archaeon, Thermococcus onnurineus. Biotechnol. Lett. 34, 75–79 10.1007/s10529-011-0732-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumer-Schuette S. E., Kataeva I., Westpheling J., Adams M. W., Kelly R. M. (2008). Extremely thermophilic microorganisms for biomass conversion: status and prospects. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 19, 210–217 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges N., Matsumi R., Imanaka T., Atomi H., Santos H. (2010). Thermococcus kodakarensis mutants deficient in di-myo-inositol phosphate use aspartate to cope with heat stress. J. Bacteriol. 192, 191–197 10.1128/JB.01115-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridger S. L., Clarkson S. M., Stirrett K., DeBarry M. B., Lipscomb G. L., Schut G. J., Westpheling J., Scott R. A., Adams M. W. (2011). Deletion strains reveal metabolic roles for key elemental sulfur-responsive proteins in Pyrococcus furiosus. J. Bacteriol. 193, 6498–6504 10.1128/JB.05445-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y., Lee H. S., Kim Y. J., Kang S. G., Kim S. J., Lee J. H. (2007). Characterization of a dUTPase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus onnurineus NA1 and its application in polymerase chain reaction amplification. Mar. Biotechnol. 9, 450–458 10.1007/s10126-006-6057-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou C. J., Jenney F. E., Jr., Adams M. W., Kelly R. M. (2008). Hydrogenesis in hyperthermophilic microorganisms: implications for biofuels. Metab. Eng. 10, 394–404 10.1016/j.ymben.2008.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danno A., Fukuda W., Yoshida M., Aki R., Tanaka T., Kanai T., Imanaka T., Fujiwara S. (2008). Expression profiles and physiological roles of two types of prefoldins from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakarensis. J. Mol. Biol. 382, 298–311 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidova I. A., Duncan K. E., Perez-Ibarra B. M., Suflita J. M. (2012). Involvement of thermophilic archaea in the biocorrosion of oil pipelines. Environ. Microbiol. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02721.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Stefano L., Vitale A., Rea I., Staiano M., Rotiroti L., Labella T., Rendina I., Aurilia V., Rossi M., D’Auria S. (2008). Enzymes and proteins from extremophiles as hyperstable probes in nanotechnology: the use of D-trehalose/D-maltose-binding protein from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus litoralis for sugars monitoring. Extremophiles 12, 69–73 10.1007/s00792-006-0058-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dev K., Santangelo T. J., Rothenburg S., Neculai D., Dey M., Sicheri F., Dever T. E., Reeve J. N., Hinnebusch A. G. (2009). Archaeal aIF2B interacts with eukaryotic translation initiation factors eIF2alpha and eIF2Balpha: implications for aIF2B function and eIF2B regulation. J. Mol. Biol. 392, 701–722 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoh T., Kanai T., Imanaka T. (2007). A highly productive system for cell-free protein synthesis using a lysate of the hyperthermophilic archaeon, Thermococcus kodakarensis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 74, 1153–1161 10.1007/s00253-006-0753-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoh T., Kanai T., Imanaka T. (2008). Effective approaches for the production of heterologous proteins using the Thermococcus kodakarensis-based translation system. J. Biotechnol. 133, 177–182 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2007.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoh T., Kanai T., Sato Y. T., Liu D. V., Yoshikawa K., Atomi H., Imanaka T. (2006). Cell-free protein synthesis at high temperatures using the lysate of a hyperthermophile. J. Biotechnol. 126, 186–195 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2006.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas J., Chung D., DeBarry M., Adams M. W., Westpheling J. (2011). Defining components of the chromosomal origin of replication of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus needed for construction of a stable replicating shuttle vector. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 6343–6349 10.1128/AEM.05057-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikane R., Ishino S., Ishino Y., Forterre P. (2010). Genetic analysis of DNA repair in the hyperthermophilic archaeon, Thermococcus kodakarensis. Genes Genet. Syst. 85, 243–257 10.1266/ggs.85.243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara S., Aki R., Yoshida M., Higashibata H., Imanaka T., Fukuda W. (2008). Expression profiles and physiological roles of two types of molecular chaperonins from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakarensis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 7306–7312 10.1128/AEM.01245-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara S., Takagi M., Imanaka T. (1998). Archaeon Pyrococcus kodakaraensis KOD1: application and evolution. Biotechnol. Annu. Rev. 4, 259–284 10.1016/S1387-2656(08)70073-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda W., Fukui T., Atomi H., Imanaka T. (2004). First characterization of an archaeal GTP-dependent phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakarensis KOD1. J. Bacteriol. 186, 4620–4627 10.1128/JB.186.14.4620-4627.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda W., Morimoto N., Imanaka T., Fujiwara S. (2008). Agmatine is essential for the cell growth of Thermococcus kodakarensis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 287, 113–120 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01303.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui T., Atomi H., Kanai T., Matsumi R., Fujiwara S., Imanaka T. (2005). Complete genome sequence of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakarensis KOD1 and comparison with Pyrococcus genomes. Genome Res. 15, 352–363 10.1101/gr.3003105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaidamaviciute E., Tauraite D., Gagilas J., Lagunavicius A. (2010). Site-directed chemical modification of archaeal Thermococcus litoralis Sh1B DNA polymerase: acquired ability to read through template-strand uracils. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1804, 1385–1393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonnet M., Erauso G., Prieur D., Le Romancer M. (2011). pAMT11, a novel plasmid isolated from a Thermococcus sp strain closely related to the virus-like integrated element TKV1 of the Thermococcus kodakarensis genome. Res. Microbiol. 162, 132–143 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorlas A., Koonin E. V., Bienvenu N., Prieur D., Geslin C. (2012). TPV1, the first virus isolated from the hyperthermophilic genus Thermococcus. Environ. Microbiol. 14, 503–516 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02662.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths K., Nayak S., Park K., Mandelman D., Modrell B., Lee J., Ng B., Gibbs M. D., Bergquist P. L. (2007). New high fidelity polymerases from Thermococcus species. Protein Expr. Purif. 52, 19–30 10.1016/j.pep.2006.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H., Nishioka M., Fujiwara S., Takagi M., Imanaka T., Inoue T., Kai Y. (2001). Crystal structure of DNA polymerase from hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus kodakaraensis KOD1. J. Mol. Biol. 306, 469–477 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata A., Kanai T., Santangelo T. J., Tajiri M., Manabe K., Reeve J. N., Imanaka T., Murakami K. S. (2008). Archaeal RNA polymerase subunits E and F are not required for transcription in vitro, but a Thermococcus kodakarensis mutant lacking subunit F is temperature-sensitive. Mol. Microbiol. 70, 623–633 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06430.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotta Y., Ezaki S., Atomi H., Imanaka T. (2002). Extremely stable and versatile carboxylesterase from a hyperthermophilic archaeon. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 3925–3931 10.1128/AEM.68.8.3925-3931.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imanaka H., Yamatsu A., Fukui T., Atomi H., Imanaka T. (2006). Phosphoenolpyruvate synthase plays an essential role for glycolysis in the modified Embden-Meyerhof pathway in Thermococcus kodakarensis. Mol. Microbiol. 61, 898–909 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05287.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imanaka T., Atomi H. (2002). Catalyzing “hot” reactions: enzymes from hyperthermophilic archaea. Chem. Rec. 2, 149–163 10.1002/tcr.10023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imanaka T., Fukui T., Fujiwara S. (2001). Chitinase from Thermococcus kodakarensis KOD1. Meth. Enzymol. 330, 319–329 10.1016/S0076-6879(01)30385-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishino S., Fujino S., Tomita H., Ogino H., Takao K., Daiyasu H., Kanai T., Atomi H., Ishino Y. (2011). Biochemical and genetical analyses of the three mcm genes from the hyperthermophilic archaeon, Thermococcus kodakarensis. Genes Cells 16, 1176–1189 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2011.01562.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumi M., Fujiwara S., Shiraki K., Takagi M., Fukui K., Imanaka T. (2001). Utilization of immobilized archaeal chaperonin for enzyme stabilization. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 91, 316–318 10.1016/S1389-1723(01)80142-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrell K. F., Walters A. D., Bochiwal C., Borgia J. M., Dickinson T., Chong J. P. (2011). Major players on the microbial stage: why archaea are important. Microbiology 157(Pt 4), 919–936 10.1099/mic.0.047837-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai T., Akerboom J., Takedomi S., van de Werken H. J., Blombach F., van der Oost J., Murakami T., Atomi H., Imanaka T. (2007). A global transcriptional regulator in Thermococcus kodakarensis controls the expression levels of both glycolytic and gluconeogenic enzyme-encoding genes. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 33659–33670 10.1074/jbc.M703424200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai T., Imanaka H., Nakajima A., Uwamori K., Omori Y., Fukui T., Atomi H., Imanaka T. (2005). Continuous hydrogen production by the hyperthermophilic archaeon, Thermococcus kodakarensis KOD1. J. Biotechnol. 116, 271–282 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2004.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai T., Matsuoka R., Beppu H., Nakajima A., Okada Y., Atomi H., Imanaka T. (2011). Distinct physiological roles of the three [NiFe]-hydrogenase orthologs in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakarensis. J. Bacteriol. 193, 3109–3116 10.1128/JB.01072-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai T., Takedomi S., Fujiwara S., Atomi H., Imanaka T. (2010). Identification of the Phr-dependent heat shock regulon in the hyperthermophilic archaeon, Thermococcus kodakarensis. J. Biochem. 147, 361–370 10.1093/jb/mvp177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly R. M., Dijkhuizen L., Leemhuis H. (2009). Starch and alpha-glucan acting enzymes, modulating their properties by directed evolution. J. Biotechnol. 140, 184–193 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2009.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. W., Peeples T. L. (2006). Screening extremophiles for bioconversion potentials. Biotechnol. Prog. 22, 1720–1724 10.1002/bp0601746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. J., Lee H. S., Kim E. S., Bae S. S., Lim J. K., Matsumi R., Lebedinsky A. V., Sokolova T. G., Kozhevnikova D. A., Cha S. S., Kim S. J., Kwon K. K., Imanaka T., Atomi H., Bonch-Osmolovskaya E. A., Lee J. H., Kang S. G. (2010). Formate-driven growth coupled with H(2) production. Nature 467, 352–355 10.1038/nature09370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobori H., Ogino M., Orita I., Nakamura S., Imanaka T., Fukui T. (2010). Characterization of NADH oxidase/NADPH polysulfide oxidoreductase and its unexpected participation in oxygen sensitivity in an anaerobic hyperthermophilic archaeon. J. Bacteriol. 192, 5192–5202 10.1128/JB.00235-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam W. L., Doolittle W. F. (1992). Mevinolin-resistant mutations identify a promoter and the gene for a eukaryote-like 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase in the archaebacterium Haloferax volcanii. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 5829–5834 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh J. A., Albers S. V., Atomi H., Allers T. (2011). Model organisms for genetics in the domain archaea: methanogens, halophiles, Thermococcales and Sulfolobales. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35, 577–608 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00265.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Pan M., Santangelo T. J., Chemnitz W., Yuan W., Edwards J. L., Hurwitz J., Reeve J. N., Kelman Z. (2011). A novel DNA nuclease is stimulated by association with the GINS complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 6114–6123 10.1093/nar/gkr504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Santangelo T. J., Cuboňová L., Reeve J. N., Kelman Z. (2010). Affinity purification of an archaeal DNA replication protein network. MBio 1, e00221-10. 10.1128/mBio.00221-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb G. L., Stirrett K., Schut G. J., Yang F., Jenney F. E., Jr., Scott R. A., Adams M. W., Westpheling J. (2011). Natural competence in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus facilitates genetic manipulation: construction of markerless deletions of genes encoding the two cytoplasmic hydrogenases. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 2232–2238 10.1128/AEM.02624-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlechild J. A. (2011). Thermophilic archaeal enzymes and applications in biocatalysis. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 39, 155–158 10.1042/BST0390155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louvel H., Kanai T., Atomi H., Reeve J. N. (2009). The Fur iron regulator-like protein is cryptic in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakarensis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 295, 117–128 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01594.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara K., Yokooji Y., Atomi H., Imanaka T. (2011). Biochemical and genetic characterization of the three metabolic routes in Thermococcus kodakarensis linking glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate and 3-phosphoglycerate. Mol. Microbiol. 81, 1300–1312 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07762.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumi R., Atomi H., Driessen A. J., van der Oost J. (2011). Isoprenoid biosynthesis in archaea – biochemical and evolutionary implications. Res. Microbiol. 162, 39–52 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumi R., Manabe K., Fukui T., Atomi H., Imanaka T. (2007). Disruption of a sugar transporter gene cluster in a hyperthermophilic archaeon using a host-marker system based on antibiotic resistance. J. Bacteriol. 189, 2683–2691 10.1128/JB.01692-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa M., Izawa Y., Rashid N., Hoaki T., Imanaka T. (1994). Purification and characterization of a thermostable thiol protease from a newly isolated hyperthermophilic Pyrococcus sp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60, 4559–4566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto N., Fukuda W., Nakajima N., Masuda T., Terui Y., Kanai T., Oshima T., Imanaka T., Fujiwara S. (2010). Dual biosynthesis pathway for longer-chain polyamines in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakarensis. J. Bacteriol. 192, 4991–5001 10.1128/JB.00279-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami T., Kanai T., Takata H., Kuriki T., Imanaka T. (2006). A novel branching enzyme of the GH-57 family in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakarensis KOD1. J. Bacteriol. 188, 5915–5924 10.1128/JB.00390-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunoura T., Takaki Y., Kakuta J., Nishi S., Sugahara J., Kazama H., Chee G. J., Hattori M., Kanai A., Atomi H., Takai K., Takami H. (2011). Insights into the evolution of Archaea and eukaryotic protein modifier systems revealed by the genome of a novel archaeal group. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 3204–3223 10.1093/nar/gkq1228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orita I., Sato T., Yurimoto H., Kato N., Atomi H., Imanaka T., Sakai Y. (2006). The ribulose monophosphate pathway substitutes for the missing pentose phosphate pathway in the archaeon Thermococcus kodakarensis. J. Bacteriol. 188, 4698–4704 10.1128/JB.00492-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan M., Santangelo T. J., Li Z., Reeve J. N., Kelman Z. (2011). Thermococcus kodakarensis encodes three MCM homologs but only one is essential. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 9671– 9680 10.1093/nar/gkr624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid N., Kanai T., Atomi H., Imanaka T. (2004). Among multiple phosphomannomutase gene orthologues, only one gene encodes a protein with phosphoglucomutase and phosphomannomutase activities in Thermococcus kodakarensis. J. Bacteriol. 186, 6070–6076 10.1128/JB.186.13.4185-4191.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rother M., Metcalf W. W. (2005). Genetic technologies for Archaea. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8, 745–751 10.1016/j.mib.2005.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo T. J., Artsimovitch I. (2011). Termination and antitermination: RNA polymerase runs a stop sign. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 319–329 10.1038/nrmicro2560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo T. J., Cubonová L., James C. L., Reeve J. N. (2007). TFB1 or TFB2 is sufficient for Thermococcus kodakarensis viability and for basal transcription in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 367, 344–357 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.12.069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo T. J., Cubonová L., Matsumi R., Atomi H., Imanaka T., Reeve J. N. (2008a). Polarity in archaeal operon transcription in Thermococcus kodakarensis. J. Bacteriol. 190, 2244–2248 10.1128/JB.01811-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo T. J., Cubonová L., Reeve J. N. (2008b). Shuttle vector expression in Thermococcus kodakarensis: contributions of cis elements to protein synthesis in a hyperthermophilic archaeon. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 3099–3104 10.1128/AEM.00305-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo T. J., Cubonová L., Reeve J. N. (2010). Thermococcus kodakarensis genetics: TK1827-encoded beta-glycosidase, new positive-selection protocol, and targeted and repetitive deletion technology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 1044–1052 10.1128/AEM.02497-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo T. J., Cubonová L., Reeve J. N. (2011). Deletion of alternative pathways for reductant recycling in Thermococcus kodakarensis increases hydrogen production. Mol. Microbiol. 81, 897–911 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07734.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo T. J., Cubonová L., Skinner K. M., Reeve J. N. (2009). Archaeal intrinsic transcription termination in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 191, 7102–7108 10.1128/JB.00982-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo T. J., Reeve J. N. (2006). Archaeal RNA polymerase is sensitive to intrinsic termination directed by transcribed and remote sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 355, 196–210 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo T. J., Reeve J. N. (2010a). Deletion of switch 3 results in an archaeal RNA polymerase that is defective in transcript elongation. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 23908–23915 10.1074/jbc.M109.094565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo T. J., Reeve J. N. (2010b). “Genetic tools and manipulations of the hyperthermophilic heterotrophic archaeon Thermococcus kodakarensis,” in Extremophiles Handbook, ed. Horikoshi K. (Tokyo: Springer; ), 567–582 [Google Scholar]

- Sato T., Atomi H. (2011). Novel metabolic pathways in Archaea. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 14, 307–314 10.1016/j.mib.2011.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T., Atomi H., Imanaka T. (2007). Archaeal type III RuBisCOs function in a pathway for AMP metabolism. Science 315, 1003–1006 10.1126/science.1135999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T., Fukui T., Atomi H., Imanaka T. (2003). Targeted gene disruption by homologous recombination in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakarensis KOD1. J. Bacteriol. 185, 210–220 10.1128/JB.185.1.210-220.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T., Fukui T., Atomi H., Imanaka T. (2005). Improved and versatile transformation system allowing multiple genetic manipulations of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakarensis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 3889–3899 10.1128/AEM.71.8.4372-4379.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T., Imanaka H., Rashid N., Fukui T., Atomi H., Imanaka T. (2004). Genetic evidence identifying the true gluconeogenic fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase in Thermococcus kodakarensis and other hyperthermophiles. J. Bacteriol. 186, 5799–5807 10.1128/JB.186.17.5799-5807.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiraki K., Tsuji M., Hashimoto Y., Fujimoto K., Fujiwara S., Takagi M., Imanaka T. (2003). Genetic, enzymatic, and structural analyses of phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase from Thermococcus kodakarensis KOD1. J. Biochem. 134, 567–574 10.1093/jb/mvg175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soler N., Gaudin M., Marguet E., Forterre P. (2011). Plasmids, viruses and virus-like membrane vesicles from Thermococcales. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 39, 36–44 10.1042/BST0390036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soler N., Justome A., Quevillon-Cheruel S., Lorieux F., Le Cam E., Marguet E., Forterre P. (2007). The rolling-circle plasmid pTN1 from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus nautilus. Mol. Microbiol. 66, 357–370 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05912.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemasa R., Yokooji Y., Yamatsu A., Atomi H., Imanaka T. (2011). Thermococcus kodakarensis as a host for gene expression and protein secretion. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 2392–2398 10.1128/AEM.01005-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumbula D. L., Whitman W. B. (1999). Genetics of Methanococcus: possibilities for functional genomics in archaea. Mol. Microbiol. 33, 1–7 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01463.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji K., Kanai T., Nomura S. M., Akiyoshi K., Negishi M., Chen Y., Atomi H., Yoshikawa K., Imanaka T. (2009). Protein synthesis in giant liposomes using the in vitro translation system of Thermococcus kodakarensis. IEEE Trans. Nanobioscience 8, 325–331 10.1109/TNB.2009.2035278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T., Matsuda T., Sakamoto N., Matsumura H., Inoue T., Morikawa M., Kanaya S., Kai Y. (2003). Crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of TBP-interacting protein from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakaraensis strain KOD1. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 59, 372–374 10.1107/S090744490202142X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokooji Y., Tomita H., Atomi H., Imanaka T. (2009). Pantoate kinase and phosphopantothenate synthetase, two novel enzymes necessary for CoA biosynthesis in the archaea. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 28137–28145 10.1074/jbc.M109.009696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]