Abstract

We compared the resistomes within polluted and unpolluted rivers, focusing on extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) genes, in particular blaCTX-M. Twelve rivers from a Portuguese hydrographic basin were sampled. Physicochemical and microbiological parameters of water quality were determined, and the results showed that 9 rivers were classified as unpolluted (UP) and that 3 were classified as polluted (P). Of the 225 cefotaxime-resistant strains isolated, 39 were identified as ESBL-producing strains, with 18 carrying a blaCTX-M gene (15 from P and 3 from UP rivers). Analysis of CTX-M nucleotide sequences showed that 17 isolates produced CTX-M from group 1 (CTX-M-1, -3, -15, and -32) and 1 CTX-M that belonged to group 9 (CTX-M-14). A genetic environment study revealed the presence of different genetic elements previously described for clinical strains. ISEcp1 was found in the upstream regions of all isolates examined. Culture-independent blaCTX-M-like libraries were comprised of 16 CTX-M gene variants, with 14 types in the P library and 4 types in UP library, varying from 68% to 99% similarity between them. Besides the much lower level of diversity among CTX-M-like genes from UP sites, the majority were similar to chromosomal ESBLs such as blaRAHN-1. The results demonstrate that the occurrence and diversity of blaCTX-M genes are clearly different between polluted and unpolluted lotic ecosystems; these findings favor the hypothesis that natural environments are reservoirs of resistant bacteria and resistance genes, where anthropogenic-driven selective pressures may be contributing to the persistence and dissemination of genes usually relevant in clinical environments.

INTRODUCTION

Antibiotics are widely used not only to treat human and animal infections but also in farms and aquacultures as food additives to promote animal growth and prevent diseases. Consequently, antibiotics are released in large amounts into natural ecosystems, where they can impact the structure and activity of environmental microbial populations (22, 23). Undoubtedly, the occurrence and dissemination of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) are recognized worldwide as a major public health concern. Efforts for the prevention of the spread of ARGs and ARB focused on clinical and human community levels, being centered especially on infection control and the restriction of antibiotic use (34). However, considering growing evidence that ARGs and pathogenic ARB are no longer restricted to clinical settings, it is quite clear that research activities need to be expanded to include nonpathogenic environmental microorganisms that could be potential sources for these ARGs (22, 23, 36, 38).

Aquatic systems can be highly impacted by human activities, receiving contaminants and bacteria from different sources and thus encouraging the promiscuous exchange and mixture of genes and genetic platforms. Consequently, these systems may promote the spread of ARB and ARGs and even the emergence of novel resistance mechanisms and pathogens (2, 3, 38). Considering the frequent detection of ARGs and ARB in aquatic systems and that their dissemination constitutes a serious public health problem, it was suggested previously that ARGs should be considered emerging environmental contaminants (23, 29).

Beta-lactam antibiotics are the most broadly used antibacterial agents. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) mediate resistance to broad-spectrum beta-lactams such as cefotaxime (CTX) and ceftazidime and are widely disseminated among Gram-negative bacteria. Since first reported in 1983 (19), the occurrence of infections caused by ESBL-producing bacteria has been constantly rising and constitutes a serious threat to human health. CTX-M genes have rapidly become the most common ESBL genes, mainly because of the genetic platforms responsible for their mobilization and dissemination (insertion sequences, integrons, transposons, and plasmids). Particularly common in the genomic environment of these genes are insertion sequences such as ISEcp1, IS26, and ISCR1 (4, 5, 8). CTX-M-15 and CTX-M-14 are the most prevalent enzymes, with over 110 CTX-M-like ESBLs described so far, found mostly in the Enterobacteriaceae but also, for example, in Aeromonas spp., Pseudomonas spp., and Acinetobacter spp. (6, 8, 25, 35). Interestingly, the CTX-M-like ESBLs are thought to have evolved from chromosomal genes of the nonclinical genus Kluyvera (28). Few studies have addressed the links between pollution and the dispersal of ARB and ARGs in natural environments. It is of major importance to understand how anthropogenic activities are modulating the resistance gene pool in order to anticipate future impacts on and consequences for the environment and public health. Also, ARGs, and specifically those most frequently found in association with pathogenic bacteria, such as CTX-M genes, may be key indicators of water quality and may be used to trace the dissemination of multiresistance in aquatic environments.

In this study, our goal was to compare the cefotaxime resistomes within polluted (P) and unpolluted (UP) lotic (flowing water) ecosystems. Specific goals were (i) to compare the occurrence and phylogenetic diversity of cefotaxime-resistant (CTXr) bacteria and ESBL producers, (ii) to detect and characterize the ESBL genes responsible for the resistance phenotype, and (iii) to compare the diversity of CTX-M-like genes using culture-dependent and culture-independent approaches.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection and water quality assessment.

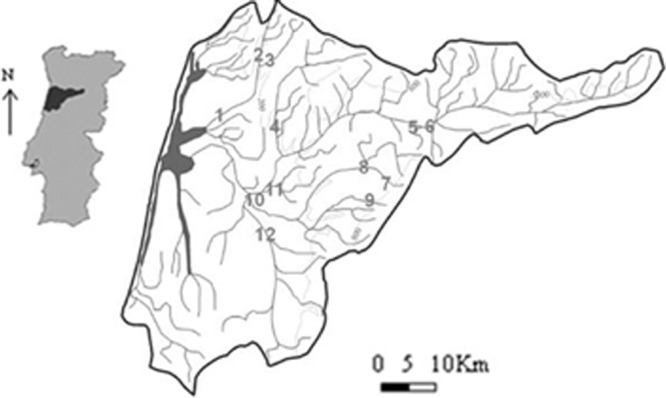

Water samples were collected at 12 sites from 11 rivers integrated in the Vouga River basin, located in central Portugal (Fig. 1). Table S1 in the supplemental material indicates the global positioning system (GPS) coordinates of all sampling locations. Throughout the basin, these water bodies are exposed to different anthropogenic impacts from agricultural, industrial, and domestic origins, which results in different levels of superficial water quality from unpolluted to extremely polluted sites (11). Sampling sites were selected in order to include putative unpolluted to extremely polluted sites. Water was collected into sterile bottles (7 liters) from 50 cm below the water surface and kept on ice for transportation. To infer the water quality, physical, chemical, and microbiological parameters were determined according to Portuguese laws (10), which included pH, color, smell, dissolved oxygen, conductivity, temperature, nitrates, chlorides, phosphates, ammonium, chemical oxygen demand, biological oxygen demand, total and fecal coliforms, and fecal streptococci. Surface water quality classification was assigned according to regulations given by the National Institute of Water (www.inag.pt), which sorts water quality into 5 categories from unpolluted to extremely polluted water in accordance with parameters established by Portuguese law.

Fig 1.

Map of the Vouga River basin (central Portugal) with the location of the 12 sampling sites under study (sites 1, 2, and 12 are polluted, and sites 3 to 9 are unpolluted).

Enumeration and selection of cefotaxime-resistant bacteria.

Water samples were filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size cellulose ester filters (Pall Life Sciences, MI), and the membranes were placed onto MacConkey agar plates supplemented with 8 μg/ml of cefotaxime to select for cefotaxime-resistant isolates. Also, to determine the proportion of cefotaxime-resistant bacteria among the total bacterial population, plates with no antibiotic supplement were used. Plates were then incubated at 37°C for 16 h. Colony counting was done in triplicate. Individual cefotaxime-resistant colonies were purified and stored in 20% glycerol at −80°C.

Molecular typing and identification of cefotaxime-resistant isolates.

Genomic DNA was isolated as previously described (17). BOX-PCR was used to type all isolates as previously described (32). PCR products were loaded onto 1.5% agarose gels for electrophoresis. The banding patterns were analyzed with GelCompar software (Applied Maths, Belgium). Similarity matrices were calculated with the Dice coefficient. Cluster analysis of similarity matrices was performed by the unweighted-pair group method using arithmetic averages (UPGMA). Isolates displaying different BOX profiles were identified by 16S rRNA gene sequencing analysis with primers and PCR conditions as previously described (17). PCR products were purified with the Jetquick PCR purification spin kit (Genomed, Löhne, Germany) and used as the template in the sequencing reactions. Online similarity searches were performed with the BLAST software at the National Center for Biotechnology Information website.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing and ESBL detection.

Antimicrobial resistance patterns against the following 16 antibiotics from 6 classes were determined by the agar disc diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar: beta-lactams (penicillins; monobactams; carbapenems; and narrow-spectrum, extended-spectrum, and “fourth-generation” cephalosporins), quinolones, aminoglycosides, phenicols, tetracyclines, and the combination sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. Discs containing the following antibacterial agents were used: amoxicillin (10 μg), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (20 μg/10 μg), ampicillin (10 μg), aztreonam (30 μg), cefepime (30 μg), cefotaxime (30 μg), ceftazidime (30 μg), cephalothin (30 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), chloramphenicol (30 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), imipenem (10 μg), kanamycin (30 μg), nalidixic acid (30 μg), sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (25 μg), and tetracycline (30 μg) (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom). After 24 h of incubation at 37°C, organisms were classified as sensitive, intermediate, or resistant according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines (7). The detection of ESBL production was carried out by a double-disc synergy test (DDST) (18) and a clavulanic acid combination disc method, based on comparing the inhibition zones of cefpodoxime (10 μg) and cefpodoxime-plus-clavulanate (10 μg/1 μg) discs (Oxoid, United Kingdom). Statistical analysis was performed by a two-sample t test with a critical P value set at 0.05.

ESBL and integrase gene screening.

PCR screening was performed for ESBL genes encoding SHV, TEM, OXA, CTX-M (groups 1, 2, 8/25, and 9), GES, VEB, and PER, with primer sets and PCR conditions described elsewhere previously (9, 16). Integrase screening was performed for the intI1, intI2, and intI3 genes (9, 16, 24). Genomic DNA of positive-control strains was used (16, 24). Each experiment included a PCR mixture containing water instead of DNA as a negative control. Amplicons were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide.

Diversity and genetic environment of blaCTX-M genes.

Sequencing was done for the blaCTX-M gene fragments amplified from the bacterial isolates. The presence of ISEcp1, IS26, IS5, orf477, IS903, and orf503 in the genetic environment of blaCTX-M was searched for by PCR (12, 13, 31).

Construction of blaCTX-M gene libraries.

To further investigate the diversity of the blaCTX-M genes in both polluted and unpolluted environments, environmental DNA from water samples was isolated as previously described (17). DNAs isolated from all polluted sites were mixed, as was also done for unpolluted samples. Hence, two clone libraries of blaCTX-M were constructed by using the TA cloning kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The blaCTX-M gene was amplified by using primers CTX-F and CTX-R (21). Clones were screened by PCR for the presence of fragments with the expected size by using primers targeting the vector. PCR products were purified and sequenced. Similarity searches were performed by using BLAST. A phylogenetic tree was obtained using MEGA, version 5 (33). The Shannon-Weaver index of diversity (H) was calculated for each library by using the formula H = −Σ(ni/N) log(ni/N), where ni is the abundance of each blaCTX-M-like type and N is the sum of the analyzed clones in each library.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

All blaCTX-M gene nucleotide sequences reported in this work have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers JQ397652 to JQ397669 (bacterial strains) and JQ397670 to JQ397721 (clone libraries). Also, 16S rRNA gene sequences are available under accession numbers JQ781502 to JQ781652.

RESULTS

Water quality and occurrence of cefotaxime-resistant bacteria.

From the analysis of all physical, chemical, and microbiological parameters (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) and according to Portuguese law (10) and the surface water quality classification given by the National Institute of Water, of the 12 sites under study, 3 sites were classified as polluted (P) and 9 were classified as unpolluted (UP). All three rivers classified as polluted presented a mixed type of pollution, related mainly to exceptionally high levels of phosphates and total coliforms (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) (10).

The total bacterial count on MacConkey agar in polluted sites was on average 1.9 × 105 CFU/100 ml of riverine water, 8.8% of which grew on MacConkey agar supplemented with cefotaxime (1.7 × 104 CFU/100 ml), and that in pristine rivers was on average 0.68 × 105 CFU/100 ml, 0.6% of which grew on MacConkey agar supplemented with cefotaxime (4.4 × 102 CFU/100 ml).

Molecular typing and identification of bacterial isolates.

Clonal relationships among cefotaxime-resistant isolates (n = 225) were assessed by BOX-PCR, and 151 isolates displaying unique BOX profiles were selected for further analysis (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Among strains isolated from polluted waters (n = 60), 41.7% were identified as Pseudomonas spp. (P. fluorescens, P. nitroreducens, P. plecoglossicida, and P. putida), 35% were affiliated with members of the Enterobacteriaceae, and 21.7% were affiliated with Aeromonas spp. The members of the Enterobacteriaceae were affiliated mostly with Escherichia coli (25%), followed by Enterobacter spp. (8.33%) and only an isolate each of Alcaligenes faecalis and Citrobacter freundii.

Of the unpolluted water isolates (n = 91), 63.7% were Pseudomonas sp. isolates (P. fluorescens, P. nitroreducens, and P. putida); 8.8% and 1.1% were Enterobacteriaceae and Aeromonas sp. (A. media and A. hydrophila) isolates, respectively; and Acinetobacter sp. appeared to be second most abundant genus in these samples, with 26.4% of isolates (all Acinetobacter calcoaceticus). Among members of the Enterobacteriaceae, Enterobacter sp. and Escherichia coli isolates were identified (5.5% and 3.3%, respectively). A 16S rRNA gene phylogenetic tree is presented in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material.

Antimicrobial susceptibility and detection of ESBL producers.

As expected, since isolates were selected in agar plates supplemented with cefotaxime, higher levels of antibiotic resistance were registered for beta-lactams (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). It was determined that 22.5% of the isolates from P and UP samples were resistant to all cephalosporins tested and that 52.3% were resistant to both cefotaxime and ceftazidime. For beta-lactams, higher percentages (although not statistically significant [P > 0.05 by a two-sample t test]) were always observed for isolates from polluted waters. For non-beta-lactam antibiotics, higher levels of resistance to quinolones (in particular, nalidixic acid, with 78.1% resistant isolates), sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, and chloramphenicol (55% and 51%, respectively) were observed. In isolates from polluted environments, resistance to tetracycline (36.7%) and to aminoglycosides (31.7%) was also frequently detected. Besides imipenem (99.3% susceptible strains), gentamicin was the most effective, with only 3.3% resistance among isolates from UP sites and 21.7% resistance among isolates from P sites. The less effective antimicrobial agents were the penicillins, the monobactam aztreonam, and narrow-spectrum and extended-spectrum cephalosporins. Significant differences in resistance frequencies among isolates from polluted and unpolluted waters toward aminoglycosides, quinolones, tetracycline, and the combination sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim were found (P < 0.05 by a two-sample t test). Multiresistance (defined as resistance to 3 or more classes of antibiotics, including beta-lactams) was found in 56.6% and 46.0% of the strains isolated from polluted and unpolluted sites, respectively.

Of the 151 isolates tested, 39 were positive for ESBL production by both methods: 27 isolates from polluted waters (13 Escherichia coli, 8 Aeromonas spp., and 6 Pseudomonas spp.) and 12 isolates from unpolluted sites (7 Pseudomonas spp., 2 Acinetobacter sp., 2 Escherichia coli, and 1 Aeromonas spp.).

Occurrence and diversity of integrase and ESBL genes.

The ESBL-producing isolates were further analyzed by PCR screening for ESBLs and integrase genes. For ESBL genes, the most frequently detected gene was blaCTX-M (n = 18), followed by blaTEM (n = 10). For 6 strains, both blaCTX-M and blaTEM were identified. Two blaVEB genes were identified, both from Aeromonas sp. isolates, once in each environment. OXA-1-like genes were detected in 6 strains isolated from polluted sites. No blaGES, blaPER, blaSHV, or blaOXA-2- and blaOXA-10-like genes were identified with the primer sets used in this study.

Among the 39 ESBL-producing isolates, the integrase genes intI1, intI2, and intI3 were screened by PCR. In 22 out of the 39 isolates, the intI1 gene was detected (19 P and 3 UP isolates), affiliated with Escherichia coli (11 P isolates and 1 UP isolate), Pseudomonas sp. (2 P isolates and 1 UP isolate), and Aeromonas sp. (6 P isolates and 1 UP isolate). The intI2 and intI3 genes were not detected.

Diversity and genetic environment of blaCTX-M genes.

Since blaCTX-M was the gene most frequently detected among the 39 ESBL-producing isolates, blaCTX-M genes were further characterized (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of blaCTX-M-producing isolates from polluted and unpolluted samplesa

| Isolate | Phylogenetic affiliation | Sample location | ESBL gene(s) detected by PCR | Antibiotic resistance profileb | intI1 Presence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | A. hydrophila | P | blaTEM, blaCTX-M | AML, AMP, AMC, KF, CTX, FEP, CIP, NA, CN, K, TE | + |

| E2 | A. hydrophila | P | blaTEM, blaCTX-M | AML, AMP, AMC, KF, CTX, FEP, NA, CN, K, TE | + |

| E3 | A. hydrophila | P | blaTEM, blaCTX-M | AML, AMP, AMC, ATM, KF, CTX, FEP, CIP, NA, K, TE | + |

| E4 | E. coli | P | blaCTX-M | AML, AMP, AMC, ATM, KF, CTX, CAZ, FEP, CIP, NA, C, CN, K, TE | − |

| E5 | E. coli | P | blaCTX-M, blaOXA | AML, AMP, AMC, ATM, KF, CTX, CAZ, FEP, CIP, NA, CN, K, SXT, TE | + |

| E6 | E. coli | P | blaTEM, blaCTX-M | AML, AMP, AMC, ATM, KF, CTX, NA, C, TE | + |

| E7 | E. coli | P | blaTEM, blaCTX-M, blaOXA | AML, AMP, AMC, ATM, KF, CTX, CAZ, FEP, CIP, NA, CN, K, SXT, TE | + |

| E8 | E. coli | P | blaCTX-M, blaOXA | AML, AMP, AMC, ATM, KF, CTX, CAZ, FEP, CIP, NA, CN, K, SXT, TE | + |

| E9 | E. coli | P | blaCTX-M | AML, AMP, ATM, KF, CTX, CAZ, FEP, CIP, NA, CN, K, SXT, TE | + |

| E10 | E. coli | P | blaCTX-M | AML, AMP, ATM, KF, CTX, CAZ, FEP, CIP, NA, K, SXT, TE | + |

| E11 | E. coli | P | blaCTX-M | AML, AMP, ATM, KF, CTX, CAZ, FEP, CIP, NA, K, SXT, TE | + |

| E12 | E. coli | P | blaCTX-M, blaOXA | AML, AMP, AMC, ATM, KF, CTX, CAZ, FEP, CIP, NA, CN, K, SXT, TE | + |

| E13 | E. coli | P | blaTEM, blaCTX-M | AML, AMP, AMC, ATM, KF, CTX, CAZ, FEP, SXT | + |

| E14 | E. coli | P | blaCTX-M | AML, AMP, ATM, KF, CTX, FEP, SXT, TE | + |

| E15 | E. coli | P | blaCTX-M | AML, AMP, AMC, ATM, KF, CTX, CAZ, FEP, NA, SXT, TE | + |

| E16 | E. coli | UP | blaCTX-M | AML, AMP, ATM, KF, CTX, CAZ, FEP, CIP, NA, SXT | + |

| E17 | E. coli | UP | blaTEM, blaCTX-M | AML, AMP, AMC, ATM, KF, CTX, CAZ, TE | − |

| E18 | Pseudomonas sp. | UP | blaCTX-M | AML, AMP, AMC, ATM, KF, CTX, NA, C, SXT | + |

Data shown include phylogenetic affiliations, sample origins, ESBL and integrase genes detected, and antimicrobial resistance profiles.

AML, amoxicillin; AMP, ampicillin; AMC, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid; KF, cephalotin; FEP, cefepime; CIP, ciprofloxacin; NA, nalidixic acid; CN, gentamicin; K, kanamycin; TE, tetracycline; ATM, aztreonam; CAZ, ceftazidime; SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; C, chloramphenicol.

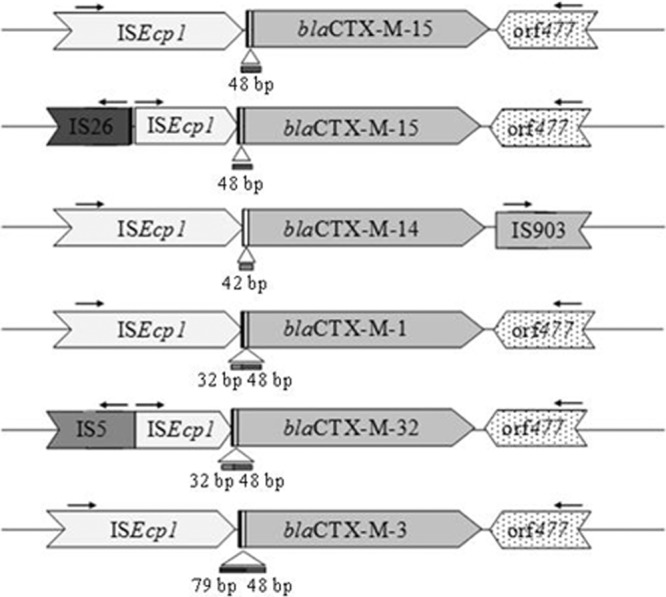

CTX-M genes were detected in 18 isolates (15 P and 3 UP isolates). The nucleotide sequences of the blaCTX-M genes were determined and their genomic environments were inspected by PCR and sequencing. Sequence analysis showed that isolates produced CTX-M from group 1 (CTX-M-1, -3, -15, and -32) and group 9 (CTX-M-14). The CTX-M-1 gene was found in 3 isolates (all from polluted water), the CTX-M-3 gene was found in 3 isolates (all from polluted water), the CTX-M-15 gene was found in 10 isolates (8 P and 2 UP isolates), and the CTX-M-32 gene was detected in only 1 isolate from unpolluted water. For group 9, the CTX-M-14 gene was found in one strain isolated from polluted water. The genetic environment study revealed the presence of 6 different genetic environments with elements previously described for clinical strains. A schematic representation of the different genomic environments found for the 18 isolates is presented in Fig. 2. ISEcp1 was found in the upstream region of all isolates examined in the present study but was disrupted in 8 isolates by IS26 and in 1 isolate by IS5. The distance between ISEcp1 and the start codon of blaCTX-M genes was as previously described (12, 20, 31), varying from 32 bp to 127 bp. All blaCTX-M genes from group 1 presented Orf477 downstream. The only blaCTX-M gene from cluster 9 detected was blaCTX-M-14 (isolate E6), which presented an IS903-like element downstream.

Fig 2.

Schematic representation of the genetic environment of CTX-M genes from the 18 isolates producing CTX-M from group 1 (CTX-M-1, -3, -15, and -32) and group 9 (CTX-M-14). The numbers of isolates from each polluted and unpolluted environment that carry each variant are indicated.

blaCTX-M-like clone libraries from polluted and unpolluted environments.

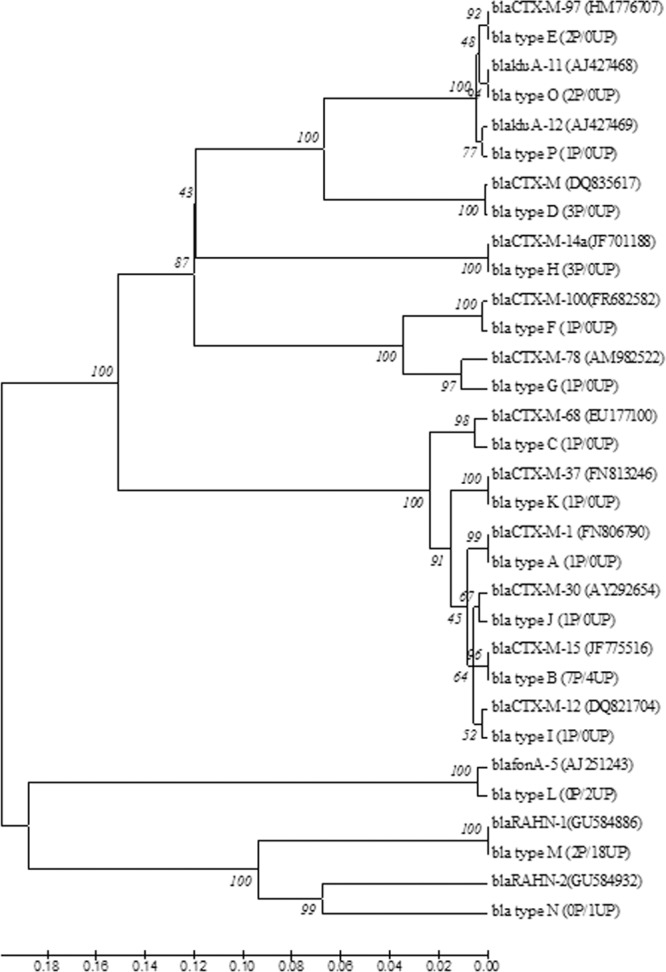

To compare the diversities of blaCTX-M genes in polluted and unpolluted environments, two clone libraries of blaCTX-M-like gene fragments were constructed and analyzed. Gene fragments were amplified by using two environmental DNA pools, each corresponding to P and UP samples, as the template. A total of 52 clones were obtained, and all inserts were sequenced (27 P and 25 UP isolates). Culture-independent blaCTX-M-like gene libraries comprised 16 gene variants (variants A to P): 14 types in the P library (H = 1.04) and 4 types in UP library (H = 0.23), with similarity values ranging from 68% to 99% between them and from 97% to 100% with sequences from the GenBank database. The majority (n = 16) were affiliated with nucleotide sequences of blaCTX-M variants from group 1 (CTX-M-1, -12, -15, -30, -37, -68, and -97), but blaCTX-M variants from group 2 (CTX-M-97) (n = 2), group 9 (CTX-M-14) (n = 3), and group 25 (CTX-M-78 and -100) (n = 2) were also identified.

Besides the much lower level of diversity among UP CTX-M-like genes, the majority were similar to chromosomal ESBLs such as blaRAHN-1, blaRAHN-2, and blaFONA-5 (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

Dendrogram tree of blaCTX-M gene sequence types A to P identified from the polluted (P) and unpolluted (UP) genomic libraries. The numbers in parentheses show the number of times that the sequence was found in the library. The branch numbers refer to the percent confidences, as estimated by a bootstrap analysis with 1,000 replications.

DISCUSSION

Lotic ecosystems are threatened daily by anthropogenic actions that compromise the quality of water and, as a consequence, its sustainable use.

Considering aquatic systems as reactors for diverse biological interactions that have important genetic implications, the study of the aquatic antibiotic resistome (which includes ARGs and pathogenic and nonpathogenic ARBs) is important, as it may indicate the extent of the alteration of water ecosystems by anthropogenic activities. Several previous studies reported the presence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria from several aquatic environments but focused on pathogenic organisms or those directly related to an environmental threat, such as hospital sewage discharges (1, 3, 36).

In this study, two groups of rivers (polluted and unpolluted), which are part of the same Portuguese lotic ecosystem, were inspected for the presence of cefotaxime-resistant Gram-negative bacteria, in order to understand how human action is modulating the environmental resistome, in particular the cefotaxime resistome.

As expected, high levels of resistance against other beta-lactams among CTXr isolates, frequently conferred by the same resistance mechanism, were found in this study (16), with a higher level of occurrence among strains from P environments. ESBL production was detected in Pseudomonas sp., Acinetobacter sp., Escherichia coli, and Aeromonas sp. isolates and was found more frequently among isolates from polluted sites. Recently, in several environmental studies, members of the same genera have been identified as ESBL producers, enforcing their relevance and importance for resistance monitoring (14, 15, 27). We investigated the presence of different ESBL genes and found blaCTX-M genes to be the most prevalent, followed by blaTEM genes. The majority of the isolated CTX-M-producing strains were affiliated with E. coli but also with Aeromonas hydrophila (3 isolates producing blaCTX-M-3) and Pseudomonas sp. (1 isolate producing blaCTX-M-15). Few studies have reported the presence of blaCTX-M genes in Pseudomonas spp. and Aeromonas spp. A previous study reported the presence of blaCTX-M-27 genes in 2 Aeromonas sp. strains isolated in river sediment (21). Also, Aeromonas sp. isolates producing blaCTX-M-3 and blaCTX-M-15 were detected previously in clinical settings and were directly implicated in human infections (37). As far as we know, this is the first work to report environmental Aeromonas sp. isolates producing blaCTX-M-3 genes. Also, for Pseudomonas spp., reports of CTX-M-producing isolates have been rare. In fact, the majority of those studies referred to clinical Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates, which were reported to produce CTX-M-1, -2, -15, and 43 (26). Also, 2 spinach saprophyte strains recently identified as P. putida and 1 strain identified as Pseudomonas teessidea were referred to as CTX-M-15-producing strains (30).

To detect any potential genetic platforms able to mobilize the blaCTX-M genes, we also analyzed the genomic environment of the 18 blaCTX-M genes detected. Different insertion sequence elements were found. An ISEcp1 element upstream of the bla gene was detected in all strains. Other IS elements (IS5 and IS26) were found but were disrupting the ISEcp1 element. The organization of IS26 and the end of ISEcp1 has been found mostly in clinical Enterobacteriaceae isolates but was also described for an E. coli blaCTX-M-1-producing strain isolated from fecal droppings of seagulls (12, 27, 31). On the other hand, the organization of IS5 and the end of ISEcp1 was found upstream of the blaCTX-M-32 gene in environmental and clinical E. coli isolates (13, 27). The presence of an ISEcp1 element upstream of blaCTX-M-1, blaCTX-M-3, blaCTX-M-14, and blaCTX-M-15 in clinical isolates was also reported previously (12, 20, 31). Downstream of the bla genes in the CTX-M-1 group, the Orf477 sequence was present in all strains. Another insertion sequence, IS903, was found downstream of the blaCTX-M-14 gene from CTX-M group 9, as described previously for clinical Enterobacteriaceae isolates (12, 20, 31). The common phenotype of multiresistance among ESBL-producing isolates is a result of the presence of other genes normally carried on the same plasmid carrying ESBL genes. This gene panoply contributes to the maintenance of ESBL-producing bacterial communities, even with a low concentration of beta-lactams (8). As reported in this work, it is of particular concern that 88.9% of the CTX-M-producing isolates are multiresistant (93.3% P and 66.6% UP isolates). Among CTX-M producers isolated from polluted waters, resistance to quinolones, aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, and the combination sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim was highly prevalent. Due to their ability to capture and incorporate gene cassettes from the environment, integrons have an important role in the spread of multidrug resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. In this work, class 1 integrons were detected in 56.4% of ESBL-producing isolates (48.7% in P and 7.7% in UP sites).

Analysis of only the cultivable fraction of Gram-negative bacteria in MacConkey agar plates might underestimate the diversity of blaCTX-M gene variants present in the lotic ecosystem under study. To overcome this methodological aspect, a culture-independent approach was applied to further analyze the diversity of blaCTX-M genes in both environments. For this, two clone libraries of blaCTX-M gene fragments amplified from polluted and unpolluted environmental DNA were constructed and analyzed. In the P library, the variety of CTX-M-like genes was much greater than that in the UP library. This is probably related to the greater anthropogenic selective pressures posed by the release of antibiotics and/or antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Also, other studies showed previously that other contaminants can also contribute to the persistence of antibiotic resistance in the environment, like, for example, heavy metals and disinfectants (22, 23). Within the P library, similarities with blaCTX-M genes from 4 clusters and also with chromosomal variants referred to as ancestors of clusters CTX-M-1 and CTX-M-2 were found. Interestingly, the majority of the blaCTX-M-like sequences found in unpolluted DNA were similar to those of chromosomal class A ESBLs that were described previously for Rahnella spp. (blaRAHN-1 and blaRAHN-2) and Serratia fonticola (blaFONA-5). In a previous study, a blaCTX-M library cloned from urban river sediment DNA also presented a high level of diversity of blaCTX-M sequences, with 13 variants being found (21). Overall, the results presented here show clear differences in polluted and unpolluted environments. While we found at most 4 variants in unpolluted rivers, with the majority being related to ancestor chromosomally located genes, up to 14 variants were found in polluted waters (from 4 out of 5 clusters identified so far for CTX-M enzymes).

A shift in the distribution of different ESBLs has recently occurred in European clinical settings, with a dramatic increase in CTX-M enzymes over TEM and SHV variants. More than 110 CTX-M variants have been described so far. Due to the high level of homology with chromosomal beta-lactamases from different Kluyvera species, these variants are now recognized as CTX-M ancestors, such as KLUA-1 from K. ascorbata and KLUG-1 from K. georgiana (5). However, the diversity that we found at polluted sites cannot be attributed to the presence of bacteria carrying ancestral CTX-M genes. As for clinics, our results suggest that CTX-M gene dominance is correlated to selective pressures imposed by human activities.

These findings sustain our hypothesis that anthropogenic activities might modulate the environmental resistance gene pool and promote antibiotic resistance dissemination. Also, we have shown that ESBL genes are a form of environmental pollution resulting either from the intake of ARGs or ARB from human activities or from the selection of resistant environmental bacteria by subtherapeutic antibiotic doses released into the environment. In our study, ESBL genes were found in genera not included in routine evaluations of water quality, associated with the genetic platforms needed for their mobilization and transfer. Thus, we suggest that data on the occurrence and diversity of ESBL genes, and specifically CTX-M genes, can be used to assess ecosystem health and antibiotic resistance evolution. However, more studies of other geographical locations are needed to validate this application. These genes are also good candidates to be used as pollution indicators. To further confirm this potential, source-tracking approaches must be conducted to link the presence of CTX-M genes to specific sources of contamination.

Conclusions.

The work here presented showed that the occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of CTXr bacteria are markedly different between polluted and unpolluted lotic ecosystems; the same happens with the occurrence and diversity of clinically relevant ESBL genes. Our results validate the hypothesis that anthropogenic impacts on water environments are modulators of the resistance gene pool and promote the dissemination of antibiotic resistance.

In addition, this work suggests that blaCTX-M-like genes may constitute indicators of pollution by antibiotics, which is useful for the study of the dispersal of antibiotic resistance in aquatic environments.

We also conclude that the dissemination of resistance to broad-range antibiotics such as cefotaxime may be at an earlier stage in pristine environments, providing the opportunity for continuing studies of the impact of anthropogenic-driven dissemination and evolution.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was financed by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) through grants SFRH/BD/43468/2008 (M.T.) and SFRH/BPD/63487/2009 (I.H.).

We thank Juliana Nina and Susana Araújo for their assistance in sample collection.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 6 April 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Allen HK, et al. 2010. Call of the wild: antibiotic resistance genes in natural environments. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8:251–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ash RJ, Mauck B, Morgan M. 2002. Antibiotic resistance of Gram-negative bacteria in rivers, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:713–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baquero F, Martinez JL, Cantón R. 2008. Antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in water environments. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 19:260–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bush K, Fisher JF. 2011. Epidemiological expansion, structural studies, and clinical challenges of new beta-lactamases from Gram-negative bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 65:455–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cantón R, Coque TM. 2006. The CTX-M beta-lactamase pandemic. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:466–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen H, et al. 2010. The profile of antibiotics resistance and integrons of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing thermotolerant coliforms isolated from the Yangtze River basin in Chongqing. Environ. Pollut. 158:2459–2464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. CLSI 2010. Performance standard for antimicrobial susceptibility testing—approved standard M100-S20. CLSI, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 8. Coque TM, Baquero F, Canton R. 2008. Increasing prevalence of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Europe. Euro Surveill. 13(48):pii=19051. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=19051 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dallenne C, Da Costa A, Decre D, Favier C, Arlet G. 2010. Development of a set of multiplex PCR assays for the detection of genes encoding important beta-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:490–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reference deleted.

- 11. DRA-Centro Direcção Regional do Ambiente-Centro 1998. Plano de bacia hidrográfica do Rio Vouga, 1a fase, análise e diagnóstico da situação de referência, anexos temáticos. DRA-Centro Direcção Regional do Ambiente-Centro, Lisbon, Portugal: http://www.arhcentro.pt/website/OLD_Plan._Bacia_Hidrogr%C3%A1fica/PGH_-_Rio_Vouga.aspx Accessed 7 February 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eckert C, Gautier V, Arlet G. 2006. DNA sequence analysis of the genetic environment of various blaCTX-M genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57:14–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fernandez A, et al. 2007. Interspecies spread of CTX-M-32 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase and the role of the insertion sequence IS1 in down-regulating blaCTX-M gene expression. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 59:841–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Girlich D, Poirel L, Nordmann P. 2011. Diversity of clavulanic acid-inhibited extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in Aeromonas spp. from the Seine River, Paris, France. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:1256–1261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14a. Government of Portugal 1998. Decree-Law no. 236/98, establishing quality standards, criteria, and objectives in order to protect the aquatic environment and improve the quality of waters in keeping with their principal uses. Diário da República, part I-A, 1 August 1998, no 176, p3676–3722 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Guenther S, Ewers C, Wieler LH. 2011. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases producing E. coli in wildlife, yet another form of environmental pollution? Front. Microbiol. 2:246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Henriques I, Moura A, Alves A, Saavedra MJ, Correia A. 2006. Analysing diversity among beta-lactamase encoding genes in aquatic environments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 56:418–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Henriques IS, Almeida A, Cunha A, Correia A. 2004. Molecular sequence analysis of prokaryotic diversity in the middle and outer sections of the Portuguese estuary Ria de Aveiro. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 49:269–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jarlier V, Nicolas MH, Fournier G, Philippon A. 1988. Extended broad-spectrum beta-lactamases conferring transferable resistance to newer beta-lactam agents in Enterobacteriaceae: hospital prevalence and susceptibility patterns. Rev. Infect. Dis. 10:867–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kliebe C, Nies BA, Meyer JF, Tolxdorff-Neutzling RM, Wiedemann B. 1985. Evolution of plasmid-coded resistance to broad-spectrum cephalosporins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 28:302–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lartigue MF, Poirel L, Nordmann P. 2004. Diversity of genetic environment of bla(CTX-M) genes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 234:201–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lu SY, et al. 2010. High diversity of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing bacteria in an urban river sediment habitat. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:5972–5976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Martinez JL. 2009. Environmental pollution by antibiotics and by antibiotic resistance determinants. Environ. Pollut. 157:2893–2902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Martinez JL. 2009. The role of natural environments in the evolution of resistance traits in pathogenic bacteria. Proc. Biol. Sci. 276:2521–2530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moura A, Pereira C, Henriques I, Correia A. 2012. Novel gene cassettes and integrons in antibiotic-resistant bacteria isolated from urban wastewaters. Res. Microbiol. 163:92–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Novais A, et al. 2010. Evolutionary trajectories of beta-lactamase CTX-M-1 cluster enzymes: predicting antibiotic resistance. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000735 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Picao RC, Poirel L, Gales AC, Nordmann P. 2009. Further identification of CTX-M-2 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2225–2226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Poeta P, et al. 2008. Seagulls of the Berlengas natural reserve of Portugal as carriers of fecal Escherichia coli harboring CTX-M and TEM extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:7439–7441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Poirel L, Kampfer P, Nordmann P. 2002. Chromosome-encoded Ambler class A beta-lactamase of Kluyvera georgiana, a probable progenitor of a subgroup of CTX-M extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:4038–4040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pruden A, Pei R, Storteboom H, Carlson KH. 2006. Antibiotic resistance genes as emerging contaminants: studies in northern Colorado. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40:7445–7450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Raphael E, Wong LK, Riley LW. 2011. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase gene sequences in Gram-negative saprophytes on retail organic and nonorganic spinach. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:1601–1607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Saladin M, et al. 2002. Diversity of CTX-M beta-lactamases and their promoter regions from Enterobacteriaceae isolated in three Parisian hospitals. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 209:161–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tacao M, Alves A, Saavedra MJ, Correia A. 2005. BOX-PCR is an adequate tool for typing Aeromonas spp. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 88:173–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tamura K, et al. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28:2731–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Taylor NG, Verner-Jeffreys DW, Baker-Austin C. 2011. Aquatic systems: maintaining, mixing and mobilising antimicrobial resistance? Trends Ecol. Evol. 26:278–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Woodford N, Turton JF, Livermore DM. 2011. Multiresistant Gram-negative bacteria: the role of high-risk clones in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35:736–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wright GD. 2010. Antibiotic resistance in the environment: a link to the clinic? Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 13:589–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ye Y, Xu XH, Li JB. 2010. Emergence of CTX-M-3, TEM-1 and a new plasmid-mediated MOX-4 AmpC in a multiresistant Aeromonas caviae isolate from a patient with pneumonia. J. Med. Microbiol. 59:843–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang XX, Zhang T, Fang HH. 2009. Antibiotic resistance genes in water environment. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 82:397–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.