Abstract

Acetone carboxylase (Acx) is a key enzyme involved in the biodegradation of acetone by bacteria. Except for the Helicobacteraceae family, genome analyses revealed that bacteria that possess an Acx, such as Cupriavidus metallidurans strain CH34, are associated with soil. The Acx of CH34 forms the heterohexameric complex α2β2γ2 and can carboxylate only acetone and 2-butanone in an ATP-dependent reaction to acetoacetate and 3-keto-2-methylbutyrate, respectively.

TEXT

Acetone is a toxic compound found in air, water, and soil, both naturally as a pollutant (5, 17) and also as a result of being produced by mammals and bacteria (8, 11, 12, 23). Acetone can also be degraded by various bacteria using a CO2-dependent pathway including acetone carboxylase as a key enzyme, a property of increasing interest for bioremediation purposes (1–3, 6, 7, 9, 10, 15, 16, 18–22). Acetone carboxylase (Acx) is a member of a protein family that also contains acetophenone carboxylase and ATP-dependent hydantoinases/oxoprolinases. While the members of this family share several similar characteristics, they differ with respect to the substrates, the products of ATP hydrolysis, and structural properties (16).

Genome analyses revealed a lot of bacterial species that possess the acetone carboxylase and thus are potentially able to detoxify acetone (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Most of these bacteria, such as Cupriavidus metallidurans, were found in soil or in contact with soil (e.g., by plant symbiosis) and belong to Proteobacteria and especially Betaproteobacteria. In the Alphaproteobacteria class, the Rhizobiales and the Rhodobacterales orders were found to contain an Acx. In the Deltaproteobacteria class, only one species (Geobacter uraniireducens Rf4), up to now, was discovered to contain an Acx, which had around 30% amino acid (aa) sequence identity with the CH34 Acx depending on the subunit. The only pathogenic species that possess the enzyme are those belonging to the Helicobacteraceae family (Epsilonproteobacteria) which are found in the mammalian stomach (4).

In general, similar gene organizations for the Acx operon were found, with three genes, acxA, acxB, and acxC, encoding the three acetone carboxylase subunits (β, α, and γ subunits, respectively) and one regulator, acxR, which was identified as a σ54- or σ70-specific transcriptional regulator and can be divergently transcribed (19). The only known paralogous enzyme with similar biochemical function is acetophenone carboxylase from Aromatoleum aromaticum (16). This enzyme consists of a hetero-octamer of four subunits whose corresponding genes apcABCDE are clustered as an operon. Acetone carboxylase does not contain a paralogue of ApcE.

Acetone carboxylase induction in Cupriavidus metallidurans.

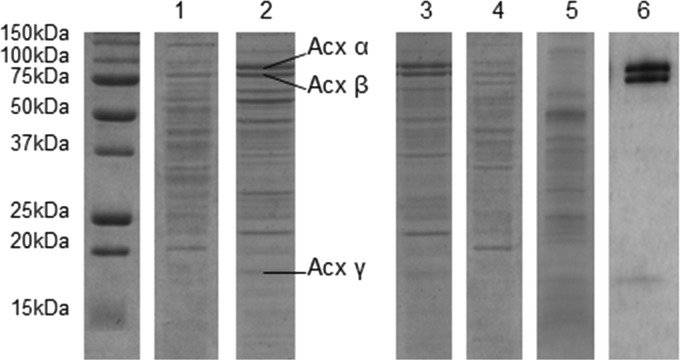

A recent study focused on acetone metabolism in C. metallidurans CH34, a betaproteobacterium found in industrial biotopes highly contaminated with metals (14), showing an overexpression of the acetone carboxylase when grown in spaceflight conditions (13). As observed in Rhodobacter capsulatus and Xanthobacter autotrophicus, the C. metallidurans Acx subunits were induced at a high level (19% ± 4% of the total proteins) when acetone was present in the culture (Fig. 1) (19, 20). An acxR knockout mutant was constructed in this study. This mutant, in which no acetone carboxylase was produced (Fig. 1), was unable to grow with acetone or isopropanol. High expression of this enzyme may compensate for a low turnover number for catalysis, allowing a reasonable rate of acetone carboxylation to support growth with a relatively low doubling time (4 to 20 h for X. autotrophicus, R. capsulatus, and C. metallidurans CH34) (19).

Fig 1.

Acetone carboxylase expression. SDS-PAGE of protein extracts (10 μg) from CH34 grown in the presence of 9 mM gluconate (1), 25 mM acetone (2), 25 mM isopropanol (3), and 25 mM n-propanol (4). (5) Protein extract (10 μg) from the acxR knockout mutant cultivated in the presence of acetone 25 mM. (6) Purified acetone carboxylase (5 μg). Molecular mass is indicated on the left.

Acetone carboxylase purification and characterization.

The partial characterization of acetone carboxylase was conducted in X. autotrophicus strain Py2, Rhodococcus rhodochrous strain B276, R. capsulatus strain B10, Alicycliphilus denitrificans strain K601, two species of Paracoccus, and very recently Aromatoleum aromaticum, showing high structural similarities (1, 6, 7, 15, 16, 18–20).

In this study, the Acx of CH34 was purified according to a two-step procedure consisting of anion DEAE-Sepharose chromatography followed by Sephacryl S300 molecular filtration (18, 19). The native molecular mass of the acetone carboxylase complex was determined by gel filtration and was estimated to be 388 ± 15 kDa, corresponding to an α2β2γ2 configuration (86, 76, and 19 kDa for the α, β, and γ subunits, respectively), as described previously in other bacteria (6, 7, 16, 18, 19). The absorption spectrum of acetone carboxylase between 250 and 350 nm exhibited a maximal peak at 287.2 nm, which is close to the value obtained in X. autotrophicus (281 nm) (18).

Enzymatic activity.

Depending on the species, the properties of Acx enzymes differ with regard to the substrates and cofactors required to support the carboxylation reaction (1, 6, 16, 18–20).

The C. metallidurans enzyme showed poor stability and maximum activity in a pH range of 6.5 to 8.0.

Of all the tested high-energy compounds (ATP, ITP, UTP, or GTP), only Mg-ATP supported acetone carboxylation in CH34, resulting in acetoacetate formation (Fig. 2). Similar results were obtained in X. autotrophicus, A. aromaticum, and R. capsulatus, while in R. rhodochrous, no activity was observed with ATP (6, 16, 19). As observed in these bacteria, the acetone carboxylase reaction in CH34 showed that ATP is hydrolyzed into AMP and 2 inorganic phosphates.

Fig 2.

Comparison of the acetone and acetophenone carboxylases from various species. 1, information obtained from reference 16; 2, information obtained from references 18 and 19; 3, information obtained from reference 19; 4, information obtained from reference 6; 5, information obtained from reference 10. A superscript “a” indicates that the products of the enzymatic reaction were not identified in X. autotrophicus and R. capsulatus; for A. aromaticum, the nature of the product was suggested by the authors but not experimentally identified. A superscript “b” indicates that the product of the enzymatic reaction was not identified. ND, not determined. +, supports the Acx reaction at different levels; −, does not support the Acx reaction.

NH4+ ions have also been shown to increase acetone carboxylase activity (19). Yet tests performed in the presence of NH4Cl (100 mM) showed no significant increase in acetoacetate production by the Acx of CH34. In contrast, as observed in X. autotrophicus, potassium (40 mM) and CO2 (KHCO3) sources stimulated the CH34 acetone carboxylase activity.

The specific activities obtained with the purified enzyme of CH34 were 0.4 to 0.6 U/mg, compared to 0.08 to 0.240 U/mg for the other Acx enzymes (6, 16, 18, 19). Nevertheless, the comparison in terms of activity has to be taken cautiously due to the differences observed with the stability of the purified enzymes.

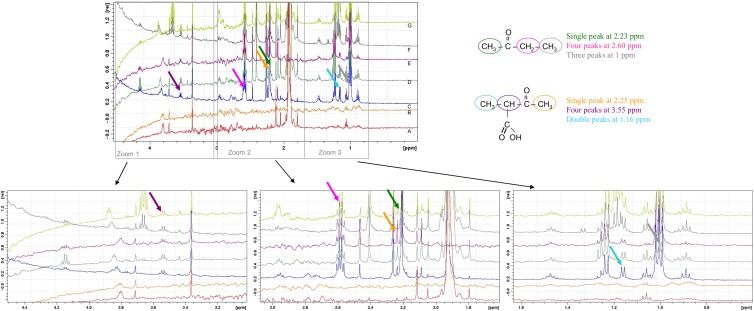

Among all the tested substrates, only acetone and 2-butanone were identified as substrates of the C. metallidurans Acx (Fig. 2). Interestingly, we showed that C. metallidurans CH34 was also able to grow in the presence of 2-butanone as the sole carbon source. Studies in X. autotrophicus and A. aromaticum also revealed that 2-butanone was the only alternative substrate of acetone carboxylase (16, 18). In R. rhodochrous, the acetone carboxylase was found to utilize a wider range of substrates, including 2-butanone, which was consumed at a rate identical to that of acetone, and also 2-pentanone, 3-pentanone, and 2-hexanone, which were degraded at rates that were 70, 40, and 42% of the rate of acetone, respectively (6). Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analyses revealed that carboxylation of 2-butanone by the Acx of CH34 produces 3-keto-2-methylbutyrate (Fig. 3). Recently, Schühle and Heider suggested that the Acx of A. aromaticum carboxylates only methyl groups adjacent to carbonyl and proposed that butanone was transformed to 3-oxopentanoic acid (16). Nevertheless, no experimental characterization of the carboxylated product was realized from butanone by the Acx of A. aromaticum (16).

Fig 3.

Determination by NMR analyses of acetone carboxylase reaction products with 2-butanone as the substrate. (A and B) Enzymatic reactions realized without substrates. (C, D, E, and F) Enzymatic reactions realized in the presence of 81.5 μg of pure Acx with 8 mM, 12 mM, 16 mM, and 24 mM ATP, respectively. (G) Enzymatic reaction realized with 16 mM ATP and 163 μg of pure Acx. ppm, parts per million.

We propose for C. metallidurans that 3-keto-2-methylbutyrate obtained by carboxylation of butanone was then activated to coenzyme A (CoA) thioester and thiolytically cleaved to propionyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA, as observed in the leucine catabolism pathway.

In conclusion, C. metallidurans CH34 is able to degrade acetone and, besides acetone, only 2-butanone using an ATP-dependent pathway including the Acx enzyme. The corresponding acx genes are located on the second chromosome or chromid.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank C. s'Heeren from the University of Mons for her technical assistance and W. Heylen and R. Van Houdt from SCK•CEN for the acxR knockout mutant construction.

This work was supported by the European Space Agency ESA/ESTEC through the PRODEX program in collaboration with the Belgian Science Policy through the MESSAGE-1 project agreement.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 6 April 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Birks SJ, Kelly DJ. 1997. Assay and properties of acetone carboxylase, a novel enzyme involved in acetone-dependent growth and CO2 fixation in Rhodobacter capsulatus and other photosynthetic and denitrifying bacteria. Microbiology 143:755–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bonnet-Smits EM, Robertson LA, Van Dijken JP, Senior E, Kuenen JG. 1988. Carbon dioxide fixation as the initial step in the metabolism of acetone by Thiosphaera pantotropha. J. Gen. Microbiol. 134:2281–2289 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boyd JM, Ellsworth H, Ensign SA. 2004. Bacterial acetone carboxylase is a manganese-dependent metalloenzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 279:46644–46651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brahmachary P, et al. 2008. The human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori has a potential acetone carboxylase that enhances its ability to colonize mice. BMC Microbiol. 8:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chowdhury BR, Das SK. 2005. Acetone—a toxic chemical. Indian Chem. Eng. B 47:277–279 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clark DD, Ensign SA. 1999. Evidence for an inducible nucleotide-dependent acetone carboxylase in Rhodococcus rhodochrous B276. J. Bacteriol. 181:2752–2758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dullius CH, Chen CY, Schink B. 2011. Nitrate-dependent degradation of acetone by Alicycliphilus and Paracoccus strains and comparison of acetone carboxylase enzymes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:6821–6825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Inui M, et al. 2008. Expression of Clostridium acetobutylicum butanol synthetic genes in Escherichia coli. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 77:1305–1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Janssen PH, Schink B. 1995. Catabolic and anabolic enzyme activities and energetics of acetone metabolism of the sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfococcus biacutus. J. Bacteriol. 177:277–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jobst B, Schühle K, Linne U, Heider J. 2010. ATP-dependent carboxylation of acetophenone by a novel type of carboxylase. J. Bacteriol. 192:1387–1394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kalapos MP. 2003. On the mammalian acetone metabolism: from chemistry to clinical implications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1621:122–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kotani T, Yamamoto T, Yurimoto H, Sakai Y, Kato N. 2003. Propane monooxygenase and NAD+-dependent secondary alcohol dehydrogenase in propane metabolism by Gordonia sp. strain TY-5. J. Bacteriol. 185:7120–7128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Leys N, et al. 2009. The response of Cupriavidus metallidurans CH34 to spaceflight in the international space station. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 96:227–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mergeay M, et al. 1985. Alcaligenes eutrophus CH34 is a facultative chemolithotroph with plasmid-bound resistance to heavy metals. J. Bacteriol. 162:328–334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nocek B, Boyd J, Ensign SA, Peters JW. 2004. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of an acetone carboxylase from Xanthobacter autotrophicus strain Py2. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60:385–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schühle K, Heider J. 2012. Acetone and butanone metabolism of the denitrifying bacterium “Aromatoleum aromaticum” demonstrates novel biochemical properties of an ATP-dependent aliphatic ketone carboxylase. J. Bacteriol. 194:131–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Singh HB, et al. 1994. Acetone in the atmosphere: distribution, sources, and sinks. J. Geophys. Res. 99:1805–1819 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sluis MK, Ensign SA. 1997. Purification and characterization of acetone carboxylase from Xanthobacter strain Py2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:8456–8461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sluis MK, et al. 2002. Biochemical, molecular, and genetic analyses of the acetone carboxylases from Xanthobacter autotrophicus strain Py2 and Rhodobacter capsulatus strain B10. J. Bacteriol. 184:2969–2977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sluis MK, Small FJ, Allen JR, Ensign SA. 1996. Involvement of an ATP-dependent carboxylase in a CO2-dependent pathway of acetone metabolism by Xanthobacter strain Py2. J. Bacteriol. 178:4020–4026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Syldatk C, May O, Altenbuchner J, Mattes R, Siemann M. 1999. Microbial hydantoinases—industrial enzymes from the origin of life? Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 51:293–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Taylor DG, Trudgill PW, Cripps RE, Harris PR. 1980. The microbial metabolism of acetone. J. Gen. Microbiol. 118:159–170 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zheng YN, et al. 2009. Problems with the microbial production of butanol. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 36:1127–1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.