Abstract

The virulence and pathogenesis mechanisms of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) strains depend on a newly described group of phenol-soluble modulin (PSM) peptides (the PSMα peptides) with cytolytic activity. These toxins are α-helical peptides with a formyl group at the N terminus, and they activate neutrophils through formyl peptide receptor 2 (FPR2), a function closely correlated to the capacity of staphylococcal species to cause invasive infections. The effects of two synthetic PSMα peptides were investigated, and we show that they utilize FPR2 and promote neutrophils to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) which in turn trigger inactivation of the peptides. Independently of FPR2, the PSMα peptides also downregulate the neutrophil response to other stimuli and exert a cytolytic effect to which apoptotic neutrophils are more sensitive than viable cells. The novel immunomodulatory functions of the PSMα peptides were sensitive to ROS generated by the neutrophil myeloperoxidase (MPO)-H2O2 system, suggesting a role for this enzyme system in counteracting bacterial virulence.

INTRODUCTION

The virulence and pathogenesis mechanisms of Staphylococcus aureus are generally regarded as very complex, and this is particularly true for virulent hypervariable global community-associated methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CA-MRSA) strains (25, 27, 38, 44, 49). In recent years, there has, however, been a dramatic rise in the incidence of severe infections in otherwise healthy individuals (25). The danger associated with CA-MRSA stems from the combination of antibiotic resistance and high virulence. The hypervariability of defined genetic elements is used as an epidemiological marker for CA-MRSA (30), and the basis for the severity of the infections is currently unfolding more clearly. Accordingly, significant efforts toward understanding the precise role of different factors/toxins generated by these bacterial strains have been made.

The recent description of a new group of phenol-soluble modulin (PSM) peptides (the PSMα peptides) (50) identifies a mechanism by which the innate immune system senses peptide toxins generated by CA-MRSA strains (28). Results in murine disease models further support the involvement of these cytolytic toxin peptides in the pathogenesis of CA-MRSA bacteria (38, 50). The PSM toxins are a family of peptides with cytotoxic activity toward neutrophils, the key effector cells in the antimicrobial innate immune defense system (28). They all have in common that they are α-helical peptides with a high degree of amphipathicity and that they are usually secreted from the bacteria without removal (deformylation) of the formyl group at the N-terminal methionyl. All PSMα peptides investigated have the same basic function, and they promote virulence through effects on discrete neutrophil functions (i.e., chemotaxis) and by being cytotoxic at higher concentrations (17, 28, 38, 43).

N-formylated peptides constitute a unique hallmark of bacterial as well as mitochondrial metabolism (41, 42), and all professional phagocytes express a pattern recognition receptor for which an N-formylated methionyl group is a critical determinant of ligand binding (23, 51). Formyl peptide receptor 1 (FPR1) is the best characterized of the neutrophil G-protein-coupled chemoattractant receptors, a group also comprising the C5a receptor, the leukotriene B4 (LTB4) receptor, the platelet-activating factor (PAF) receptor, as well as a second member of the FPR family, FPR2 (35). The two neutrophil FPRs are structurally very similar, but they bind and are activated by different agonists (23). FPR2 hardly recognizes the classic formylated bacterial peptides sensed by FPR1 (23, 51), but the formylated cytotoxic PSMα peptides are specific for FPR2 rather than for FPR1 (28). The precise biological roles of FPR2 are not completely understood, but the identification of both exogenous and endogenous ligands involved in inflammation strongly indicates a pivotal role of this receptor in regulating inflammatory defense reactions (51). It should be noticed that the release of PSMα peptides as well as their ability to activate FPR2 is a function closely correlated to the capacity of staphylococcal species to cause invasive infections (43), suggesting a complex interplay between the microbe and the innate immune system. The dual function of the PSMα peptides, on the one hand being cytotoxic through membrane-perturbing activities and on the other hand having immunoregulatory functions through direct binding to FPR2, is a character also shared by some other host defense/bacterial virulence peptides: LL-37, the human cationic antimicrobial peptide belonging to the cathelicidin family (4), and the cecropin-like peptide Hp2-20, a virulence-promoting peptide from Helicobacter pylori. LL-37 and Hp2-20 also contain the same type of amphipathic α-helical structure that can permeate membranes and ultimately kill not only host cells but also microorganisms (1, 2). In addition, almost all earlier described FPR2 agonists also activate the neutrophil NADPH oxidase to produce and release reactive oxygen species (ROS) that directly or indirectly take part in the resolution of inflammatory reactions (5, 6, 23). It is also interesting to note that the cationic host defense peptide LL-37 selectively permeabilizes the plasma membrane of apoptotic neutrophils (2, 52).

In this study, we have investigated the immunomodulatory effects of two PSMα peptides, PSMα2 and PSMα3. Both peptides activate human neutrophils to produce ROS, and FPR2 is the receptor used. The PSMα peptides simultaneously, but independently of FPR2, transfer neutrophils to a suppressed state characterized by a diminished response to other stimuli that induce ROS production. The PSMα peptides also display cytotoxicity against apoptotic neutrophils, and this effect was independent of FPR2. We also show that the PSMα peptides triggered their own inactivation, a process involving H2O2 released from neutrophils and the granule enzyme myeloperoxidase (MPO).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

The chemoattractant N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLF), EGTA, isoluminol, superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and H2O2 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and the horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was from Roche Diagnostics (Bromma, Sweden). The fluorescence-labeled fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated formylated hexapeptide (fNLPNTL) was from Molecular Probes, and the chemoattractant WKYMVM was synthesized and purified by high-performance liquid chromatography by Alta Bioscience (University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom). PSMα2 (fMGIIAGIIKVIKSLIEQFTGK) and PSMα3 (fMEFVAKLFKFFKDLLGKFLGNN) in their N-formylated forms were synthesized by American Peptide Company (Sunnyvale, CA). All peptide stocks were made in dimethyl sulfoxide, and further dilutions were made in Krebs-Ringer phosphate buffer containing glucose (10 mM), Ca2+ (1 mM), and Mg2+ (1.2 mM) (KRG; pH 7.3). MPO was obtained from Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany). WRWWWW (WRW4) was from Genscript Corporation (Scotch Plains, NJ), and cyclosporine H was kindly provided by Novartis Pharma (Basel, Switzerland). Ficoll-Paque was obtained from Amersham Biosciences. The FPR2-specific gelsolin-derived inhibitory peptide PBP10 (gelsolin residues 160 to 169 [21]) was synthesized by CASLO Laboratory (Lyngby, Denmark). CD95 (fatty acid synthase [FAS]) monoclonal antibody (functional grade) was from Nordic BioSite (Täby, Sweden). Annexin V–5(6)-carboxyfluorescein-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (FLUOS) was from Roche Diagnostics (Mannheim, Germany), and ToPro3 dye was from Invitrogen, Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). RPMI 1640, fetal calf serum (FCS), PEST, and G418 were from PAA Laboratories GmbH, Austria.

Compound 43, an earlier described FPR1 agonist (21a), was a generous gift from Amgen (Thousand Oaks, CA).

Expression of formyl peptide receptors in HL-60 cells.

The procedures used to obtain stable expression of FPR1 and FPR2 in undifferentiated HL-60 cells have been previously described (14). To prevent possible autodifferentiation due to the accumulation of differentiation factors in the culture medium, cells were passed twice a week before they reached a density of 2 × 106 cells/ml. At each passage, an aliquot of the cell culture was centrifuged, the supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellet was resuspended in fresh medium RPMI 1640 containing FCS (10%), PEST (1%), and G418 (1 mg/ml).

Isolation of human neutrophils from peripheral blood.

Blood neutrophils were isolated from buffy coats from healthy volunteers as described by Boyum et al. (3). After dextran sedimentation at 1 × g and hypotonic lysis of the remaining erythrocytes, the neutrophils obtained by centrifugation in a Ficoll-Paque gradient were washed twice in KRG. The cells were resuspended in KRG (1 × 107/ml) and stored on ice until use.

Measurement of superoxide anion production.

The production of superoxide anion by the neutrophil NADPH oxidase was measured by isoluminol/luminol-amplified chemiluminescence (CL) in a six-channel Biolumat LB 9505 apparatus (Berthold Co., Wildbad, Germany) as described earlier (15, 16). In short, 2 × 105/ml neutrophils were mixed (in a total volume of 900 μl) with HRP (4 U) and isoluminol (6 × 10−5 M) in KRG that had been preincubated at 37°C, after which the stimulus (100 μl) was added. The isoluminol/HRP technique detects the release of superoxide and is independent of H2O2 (15, 16). Intracellular ROS were measured with luminol in the presence of SOD and catalase. The light emission was recorded continuously. When required, the specific receptor inhibitors were included in the CL mixture for 5 min at 37°C before stimulation. By a direct comparison of the SOD-inhibitable reduction of cytochrome c and SOD-inhibitable CL, 7.2 × 107 counts were found to correspond to the production of 1 nmol of superoxide (a millimolar extinction coefficient for cytochrome c of 21.1 was used).

Determination of changes in cytosolic calcium.

Cells were resuspended at a density of 2 × 107 cells/ml in KRG containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and loaded with 2 μM fura-2-acetoxymethyl ester (Fura 2-AM; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 30 min at room temperature. The cells were then washed and resuspended in KRG at a density of 2 × 107 cells/ml. The amount of cells used in the assay was 2 × 106 cells/measuring cuvette. Calcium measurements were carried out with a Perkin Elmer fluorescence spectrophotometer (LS50) with excitation wavelengths of 340 and 380 nm and an emission wavelength of 509 nm. The transient rise in intracellular calcium is presented as a ratio of fluorescence changes (340 nm/380 nm) (26).

Treatment of peptides with the MPO-H2O2 enzyme system.

Peptide agonist fMLF (10−6 M), WKYMVM (10−6 M), or PSMα2 or PSMα3 (2 × 10−6 M) diluted in KRG was incubated with MPO (1 μg/ml) at 37°C for 5 min before the addition of H2O2 (final concentration, 10 μM), and the samples were incubated for another 10 min at ambient temperature. Control peptides were incubated under the same conditions but without any additive. The activity of the peptides was determined through their potential to trigger or inhibit the ROS release or induce cytotoxicity in neutrophils. We cannot completely rule out the possibility that treated and untreated peptides differed in their propensity to stick to the tube walls, but in order to minimize this risk, some of the peptide inactivation experiments were performed in Eppendorf tubes specially designed for low protein binding (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany). The type of plastic tubes used did not have any impact on the results obtained.

Assessment of PSMα peptide-induced cytotoxicity.

Freshly isolated neutrophils were washed twice and resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% PEST to a density of 5 × 106 cells/ml. Cells (200 μl) were added to polypropylene tubes and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 20 h to allow a part of the neutrophil population to spontaneously go into apoptosis (2, 7). The mixed neutrophil population was washed and resuspended in 100 μl annexin V binding buffer (10 mM HEPES, 140 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4) with addition of annexin V-FLUOS (2 μl). Samples were stained with annexin V-FLUOS in the dark for 5 min at ambient temperature, after which ToPro3 was added and the staining was continued for another 5 min. Interaction of cells with PSMα peptides was carried out on ice or at 37°C before examination on an Accuri C6 flow cytometer (Accuri, United Kingdom).

Morphological changes in neutrophils induced by the PSMα peptides were inspected by light microscopy (magnification, ×40) of cytospin preparations after Giemsa/May-Grünwald staining. Release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was assayed with a kit from Roche Diagnostics (Mannheim, Germany) according to the description by the manufacturer. Cytotoxicity of PSMα peptides on bacterial membranes was assessed with an inhibition zone assay as previously described (22).

Determinations of receptor exposure by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis.

To determine the effect of PSMα2 on ligand binding to FPR1, an FITC-conjugated formylated hexapeptide (FITC-fNLPNTL; final concentration, 10−9 M) was added to neutrophils on ice. The PSMα peptides were added to neutrophils in the absence or presence of nonlabeled fMLF (10−7 M). The cells were then incubated at 4°C for 30 min, and no washing was performed after labeling. Specific binding was calculated by subtracting the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for unspecific binding (with unlabeled probe) from the MFI for total binding (without unlabeled probe) for each sample using an Accuri C6 flow cytometer, and results are given in fluorescence units (FlU).

Statistical analysis.

One-way analysis of variance with Dunnett's multiple-comparison test or two-tailed, unpaired Student's t test was used for statistical analysis. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistical significant.

RESULTS

PSMα peptides trigger a rise of intracellular Ca2+ in primary human neutrophils and in FPR2-expressing HL-60 cells.

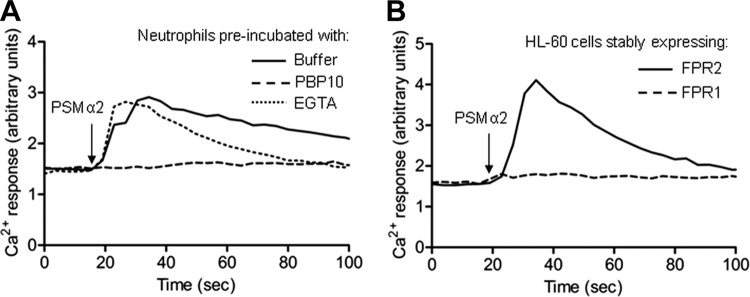

It was recently shown that PSMα peptides derived from CA-MRSA in their formylated form are high-affinity agonists for FPR2 in human neutrophils, as determined through the effect of FLIPr, an FPR2-specific antagonist (40) that completely abrogated the Ca2+ influx induced by PSMα peptides in these cells (28). In agreement with earlier published data, we confirmed the receptor preference for PSMα peptides among FPRs using a unique selective FPR2 inhibitor, PBP10, acting on the cytosolic parts of the receptor (19, 21). The transient rise in intracellular Ca2+ induced in neutrophils by PSMα2 or PSMα3 was inhibited by PBP10 (shown for PSMα2 in Fig. 1A), whereas the FPR1-specific antagonist cyclosporine H (46) was without any effect (data not shown). The receptor preference for FPR2 was further confirmed using HL-60 cells stably expressing either FPR1 or FPR2. Stimulation of cells overexpressing FPR2 with either PSMα2 (Fig. 1B) or PSMα3 (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material) induced a robust transient increase in intracellular Ca2+ with an equal potency, and the kinetics were indistinguishable from those induced by the specific FPR2 agonist WKYMVM (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material). When higher concentrations (>100 nM) were used, the PSMα peptides induced a response with somewhat different kinetics: a rapid rise in intracellular Ca2+ was induced, but this was not followed by a decline to basal levels (data not shown). No transient Ca2+ was observed when FPR1-overexpressing cells were used (Fig. 1B), further demonstrating that FPR2 is the preferred receptor for PSMα peptides.

Fig 1.

PSMα2 induces a transient change in cytosolic calcium in human neutrophils and FPR2-overexpressing HL-60 cells. (A) Fura-2-labeled primary human neutrophils were incubated without any additive (buffer control), with the specific FPR2 inhibitor PBP10 (1 μM), or with EGTA (2.5 mM). The PSMα2 peptide (1 nM) was added (arrow), and the concentration of free cytosolic Ca2+ was monitored by the Fura-2 fluorescence. Traces of representative calcium responses are shown, and the experiments have been performed at least three times. Abscissa, time of study (seconds); ordinate, fluorescence (arbitrary units). (B) Ca2+ response induced by the PSMα2 peptide (5 nM) in transfected HL-60 cells overexpressing either FPR1 or FPR2. Traces of representative calcium responses are shown, and the experiments have been performed at least three times.

Removal of extracellular Ca2+ by EGTA had negligible effects on the rise of cytosolic free Ca2+ in human neutrophils induced by either PSMα2 or PSMα3 (shown for PSMα2 in Fig. 1A), suggesting that PSMα peptides primarily trigger a release of Ca2+ from the intracellular storage organelles. This finding is in agreement with our earlier findings when using other FPR2 agonists demonstrating that FPR2 triggers a classic intracellular Ca2+ response identical to that triggered by FPR1 (19, 26).

In summary, these data confirm that formylated PSMα peptides derived from CA-MRSA are indeed specific agonists for FPR2 in human neutrophils and trigger the same type of calcium response as other FPR2 agonists.

PSMα peptides trigger FPR2-dependent release of superoxide anion from human neutrophils.

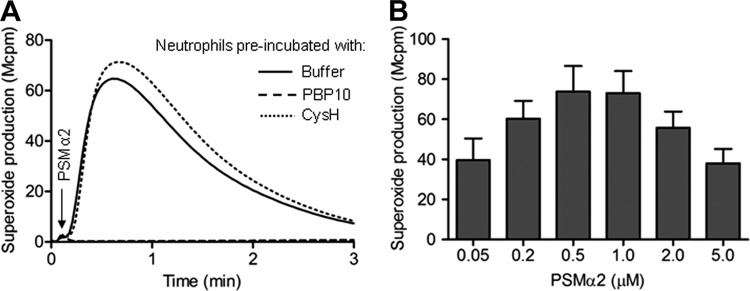

Nanomolar concentrations of PSMα peptides have been shown to trigger proinflammatory neutrophil responses such as chemotaxis and secretion of the chemokine interleukin-8 (28). To further explore the proinflammatory effects of the PSMα peptides in relation to neutrophils, we measured and characterized the oxidase activity induced by the peptides. The NADPH oxidase was assembled, and neutrophils were produced and released superoxide anions when triggered with either of the two PSMα peptides. The magnitude and kinetics of the responses were very similar to those induced by fMLF (an FPR1 agonist) or WKYMVM (another FPR2 agonist; shown for PSMα2 in Fig. 2A). No superoxide production was induced by PSMα peptides in the presence of the selective FPR2 inhibitor PBP10 (Fig. 2A), suggesting that FPR2 is also the preferred receptor for activation of the oxidase. This suggestion gains support from the fact that the response was also inhibited when PBP10 was replaced by another FPR2 antagonist, WRW4 (46) (data not shown), but not by the FPR1-specific antagonist cyclosporine H (Fig. 2A). The amounts of superoxide secreted increased dose dependently over a concentration range of the PSMα2 peptides of up to 0.5 μM (Fig. 2B). Increasing peptide concentrations further resulted in decreased superoxide production (Fig. 2B). Similar results were obtained with PSMα3 (data not shown).

Fig 2.

The PSMα2 peptide triggers superoxide production from human neutrophils. (A) Primary human neutrophils were left without any additive (buffer control) or incubated together with the FPR1-specific antagonist cyclosporine H (CysH; 1 μM) or the FPR2-specific inhibitor PBP10 (1 μM) for 5 min at 37°C. The PSMα2 peptide (100 nM) was added (arrow) to cells, and the release of superoxide anions was recorded continuously. A representative experiment out of more than five is shown. (B) Dose-dependent superoxide production induced by the PSMα2 peptide is also shown, and the data presented represent mean peak values + SEM (n = 3).

Neutrophils are capable of NADPH oxidase assembly in nonphagosomal intracellular membranes, resulting in ROS production within intracellular organelles also in the absence of phagocytosis (5). We have earlier shown that pneumolysin, a toxin released from Streptococcus pneumoniae cells undergoing autolysis, activates the neutrophil NADPH oxidase in intracellular organelles (33). No intracellular ROS production was, however, induced by the PSMα peptides, determined with concentrations of up to 1 mM (data not shown).

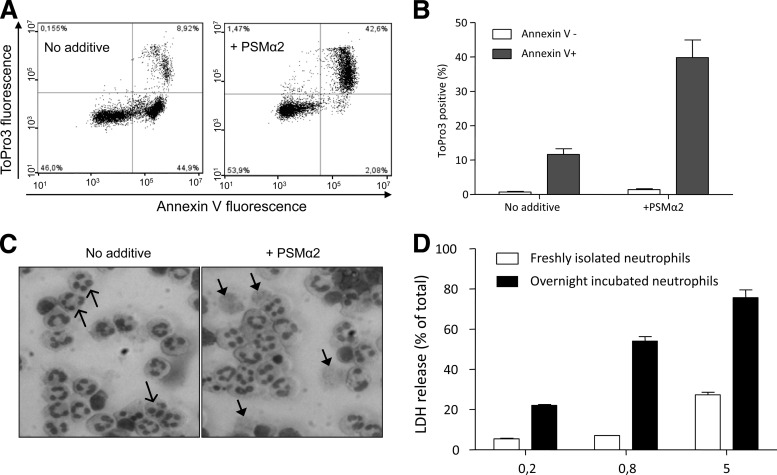

PSMα peptides permeabilize the membranes of apoptotic neutrophils.

The neutrophil plasma membrane has been shown to be permeabilized by PSMα peptides when present in micromolar concentrations, whereas nanomolar concentrations trigger proinflammatory responses such as chemotaxis and superoxide release (28) (see above). Also, LL-37, the earlier mentioned cationic antimicrobial peptide, interacts with the neutrophil plasma membrane but with a profound difference in sensitivity between viable and apoptotic neutrophils (2, 52). Accordingly, we determined the effects of the PSMα peptides on a mixed population of viable and apoptotic cells achieved through incubation of freshly isolated neutrophils overnight. Our standard protocol gives rise to a cell population containing roughly equal numbers of viable (annexin V negative [annexin V−] and ToPro3 negative [ToPro3−]) and apoptotic (annexin V positive [annexin V+] and ToPro3−) neutrophils, as assessed by flow cytometry (Fig. 3A, left). Very few cells (5 to 10%) possess a necrotic phenotype with leaky/permeable cell membranes (annexin V+ and ToPro3+; Fig. 3A, left). The relation between the number of viable cells and the number of apoptotic cells was dramatically changed upon the addition of PSMα2 or PSMα3 to overnight-cultured neutrophils (shown for PSMα2 in Fig. 3A, right). The necrotic phenotype increased significantly after addition of PSMα2, and the increase was peptide concentration dependent (tested at concentrations of up to 1 μM). The cytolytic effect of PSMα peptides on apoptotic neutrophils was fairly rapid and already seen after an interaction time of 5 min (data not shown). Prolonged incubation up to 30 min resulted in a moderately increased permeabilization effect, as determined by the number of cells transferred from the apoptotic to the necrotic gate, and the selectivity was retained as viable cells remained intact. Prolonging the time of interaction at 4°C further did not result in any higher/increased effect (data not shown). The same type of selectivity was obtained when the neutrophil-PSMα2 interaction was allowed to proceed at 37°C, but the number of structurally intact necrotic cells decreased when the incubation time was prolonged (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

Fig 3.

The PSMα2 peptide selectively permeabilizes apoptotic neutrophils. (A) Primary human neutrophils were incubated overnight (about 20 h) to allow approximately 50% of the cells to spontaneously enter apoptosis. Remaining cells are mostly viable (annexin V− and ToPro3−) or apoptotic (annexin V+ and ToPro3−) with only occasional necrotic cells (annexin V+ and ToPro3+), as assessed by flow cytometry (left). The necrotic shift of almost all apoptotic cells induced by PSMα2 (800 nM) during 30 min incubation on ice was determined (right). Representative plots out of at least five independent experiments are shown. (B) PSMα2 (800 nM) shifted the apoptotic population to be necrotic (annexin V+, ToPro3+) but did not affect the viable neutrophils (annexin V−). The figures show mean values from the experiments performed (mean ± SEM, n = 11). (C) Morphological changes in neutrophils induced by the PSMα2 peptide. Light microscopic inspection of cytospin preparations made of neutrophils incubated overnight without any additive showed a mixture of viable and apoptotic cells (left). When these cells were incubated with PSMα2 (800 nM; right), necrotic cells were seen. Apoptotic and necrotic neutrophils are indicated by open and closed arrowheads, respectively. (D) Supernatants from freshly prepared or overnight-incubated neutrophils treated with various concentration of PSMα2 on ice for 30 min were assessed for LDH content. The experiment shown was performed in triplicate, and results are expressed as percent total release obtained in the presence of Triton X-100 (mean ± SEM).

The increase of the necrotic phenotype was achieved primarily at the expense of the apoptotic neutrophil population, as none of the concentrations of peptide tested displayed a cytotoxic effect on the viable (annexin V−) subpopulation of neutrophils (Fig. 3A, right, and summarized in Fig. 3B). This suggests that apoptotic neutrophils are more sensitive to the cytolytic effect of PSMα peptides than viable neutrophils. This was further confirmed by using either a population of freshly isolated neutrophils containing only viable cells (see Fig. S3, top, in the supplemental material) or more homogeneous apoptotic neutrophils following incubation with FAS ligand (see Fig. S3, middle, in the supplemental material). The sensitivity of apoptotic cells and resistance of viable cells to nanomolar concentrations of the PSMα peptides were also confirmed morphologically (Fig. 3C) and through the measurements of LDH release (Fig. 3D), showing a difference in sensitivity to the PSM peptides between a mixed population containing apoptotic/viable neutrophils and one containing only viable cells. With very high peptide concentrations (5 μM), viable cells were also affected (Fig. 3D), which is in agreement with earlier published data (28). The presence of the specific FPR2 inhibitor PBP10 did not reduce the ability of PSMα2 to permeabilize the membranes of apoptotic neutrophils (see Fig. S3, bottom, in the supplemental material), showing that the cytotoxicity is independent of FPR2. The same results were obtained when PSMα2 was replaced by PSMα3 (data not shown).

Not only viable neutrophils but also bacteria resisted the cytotoxic effect of the PSMα peptides, suggesting that the selectivity was restricted to apoptotic eukaryotic cells. This conclusion is based on our results obtained using an inhibition zone assay in which no bactericidal effect was observed when either Gram-negative Escherichia coli or Gram-positive S. aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis were grown in agarose plates in the presence of PSMα peptides (shown for PSMα2 in Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). It should be noticed, however, that other PSMs have been shown to be bactericidal (13), suggesting differences depending both on the type of PSM peptide used and on the target bacterium.

Taken together, our data show that PSMα peptides at concentrations that induce proinflammatory activities also display a direct cytolytic effect on apoptotic cells and this effect is independent of FPR2.

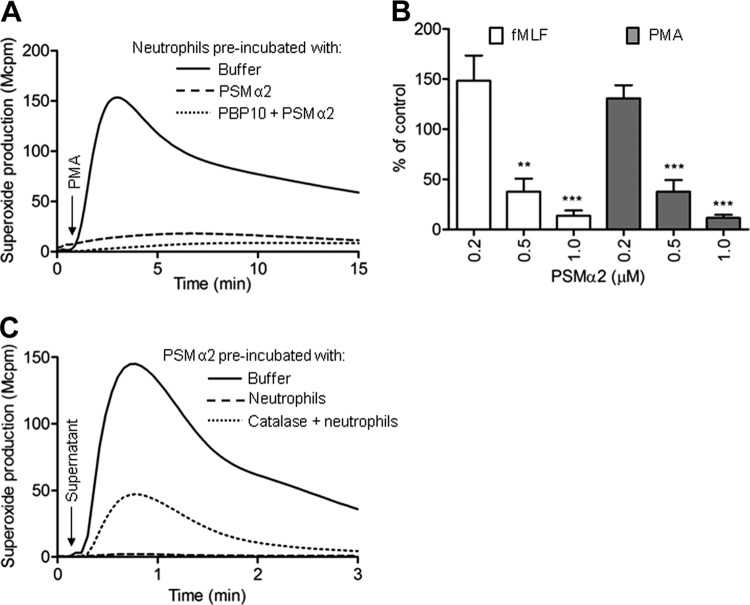

PSMα peptides downregulate the neutrophil response to other stimuli and induce their own inactivation.

We next investigated whether PSMα peptides at nanomolar concentrations could modulate neutrophil responses to other stimuli. PSMα peptides at high nanomolar concentrations transferred the cells to a refractory state with reduced ROS production induced by either the protein kinase C (PKC)-activating phorbol ester phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) (Fig. 4A and B) or fMLF (Fig. 4B). In order to exclude the possibility that the reduced fMLF response after PSM treatment was due to a downregulation of the receptor (FPR1) for this peptide, we measured the surface expression of FPR1 using an FITC-labeled FPR1 agonist and compared the specific binding to human neutrophils before and after PSMα treatment. PSMα treatment resulted in an unchanged (or slightly increased at higher concentrations) background binding, but in increased FPR1-specific binding (specific binding for control cells = 780 FlU, 0.5 μM PSMα = 950 FlU, 1 μM PSMα = 1,010 FlU), suggesting a somewhat increased expression of FPR1 compared to that by control cells. Receptor upregulation due to granule mobilization is likely to explain this observation and could also explain the priming of the response to fMLF when low concentrations of the PSM peptides were used (Fig. 4B).

Fig 4.

Interaction of neutrophils with PSMα2 transfers the cells to a suppressed state and leads to inactivation of the peptides. (A and B) Neutrophils were incubated at 37°C for 10 min with (dotted line) or without (dashed line) PBP10. The PSMα2 peptide was then added and the incubation was continued for an additional 10 min. Control cells (solid line) were incubated for the same time without any additive. The cells were then activated with PMA (5 × 10−8 M; time of addition is indicated by the arrow in panel A) or fMLF (10−7 M), and the production of superoxide was measured. (A) Results of a representative experiment with 1 μM PSMα2 and with PMA as the stimulus. (B) The results for both fMLF and PMA are summarized and given as a percentage of the control (mean + SEM, n = 3; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001)). (C) Neutrophils (106/ml) were incubated at 37°C for 10 min with the PSMα2 peptide (1 μM) in the absence (dashed) or presence (dotted line) of catalase. The cells were then removed by two centrifugation steps, and the remaining cell-free supernatant was used to stimulate a new batch of freshly prepared neutrophils (final peptide concentration, 0.1 μM). For comparison, the activity induced by the control supernatant (solid line; prepared without neutrophils) is also shown. The time point for addition of the supernatants is indicated by an arrow, and the amount of superoxide is given as light emission and expressed in 10−6 cpm (Mcpm).

Our finding that PSM-treated cells produce reduced amounts of ROS in response to PMA could possibly be that cells that have already undergone one burst in respiration produce less ROS when exposed to a second stimulus. We tested this by allowing the PSM peptides to interact with the neutrophils at 15°C or lower temperatures at which the peptide binds its receptor without activation of the oxidase (29). When the cells were then transferred to 37°C and subsequently activated with PMA, the response was reduced in the PSM-treated neutrophils (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). These data suggest that the inhibition induced by the PSMα peptide is not due to consumption of oxidase components. It is also important to notice that the cells with a reduced capacity to generate ROS were not dead and resisted the uptake of viability dye ToPro3 (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material) and the refractory state was also induced in the presence of PBP10 (shown for PMA in Fig. 4A), suggesting that inhibition was independent of direct cytotoxicity as well as of FPR2.

Many chemoattractants, including the FPR1-specific agonist fMLF and the FPR2-specific agonist WKYMVM, can trigger their own inactivation upon interaction with human neutrophils (9, 20). This inactivation is mediated through a combined action of H2O2 generated by the neutrophil NADPH oxidase and the granule enzyme MPO (12). The remaining neutrophil-activating capacity in a cell-free supernatant obtained from neutrophils stimulated with PSMα peptides was determined, and reduced activity when tested on a fresh batch of cells reflects inactivation of the peptides. The NADPH-activating capacity of the PSMα peptides was reduced by more than 90% (mean remaining peak activity ± standard deviation [SD], 9% ± 7%; n = 5) following interaction with neutrophils (shown for PSMα2 in Fig. 4C). In agreement with the suggested mechanism of triggering of peptide inactivation by the MPO-H2O2 system, the presence of catalase during the initial interaction partly restored the PSMα activity (Fig. 4C). The fact that some inhibition was also obtained in the presence of catalase could be due to either an alternative (H2O2-independent) mechanism for inactivation of peptides or loss of peptides from supernatants through endocytosis during the initial interaction.

The MPO-H2O2 enzyme system inactivates the immunomodulatory effects of the PSMα peptides.

In peptide inhibition experiments, it is of utmost importance that the same amounts of peptides are compared. In order to obtain these, we used a cell-free inactivation system and compared the potency of MPO-H2O2-treated peptides with that of the same concentration of nontreated peptide solutions. In agreement with the data presented above (Fig. 4C), the neutrophil NADPH-activating capacity of PSMα peptides was largely lost following interaction with MPO and H2O2 (shown for PSMα2 in Fig. 5A), with a remaining activity of about 5% (mean remaining peak activity ± SD, 3% ± 2%; n = 5). For comparison, the activity of an FPR1 agonist, compound 43 (H. Forsman, 2011, no. 52), earlier shown to be MPO-H2O2 insensitive (H. Forsman, 2011, no. 65), was determined in parallel; no activity was lost by incubating compound 43 with MPO and H2O2 (see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material). PSMα peptides treated with either MPO or H2O2 alone displayed full activity in triggering a fresh batch of cells to produce ROS (data not shown), further supporting the inactivation mechanism involving both MPO and H2O2 (12). The cytotoxic effect on apoptotic cells, as well as the suppressive effect on viable neutrophil functions induced by nanomolar concentrations of PSM peptides, was diminished after treating the peptides with MPO and H2O2 (Fig. 5B and C). In summary, we show that the MPO-H2O2 enzyme system inactivates not only the proinflammatory effect of PSMα peptides but also the cytotoxic effect of the peptides on apoptotic neutrophils.

Fig 5.

Inactivation of PSMα2 by the MPO-H2O2 enzyme system. (A) The PSMα2 peptide (200 nM) is inactivated by the MPO-H2O2 system, as shown by the reduced ability of the MPO-H2O2-treated peptide (dashed line) to trigger neutrophil NADPH oxidase activity. For comparison, the response induced by the nontreated peptide (solid line) is shown as a control. (B) The MPO-H2O2 system also inactivates the cytolytic activity of PSMα2. Control (nontreated peptide; light gray bars) or MPO-H2O2-treated PSMα2 (dark gray bars) was added to the mixed (viable/apoptotic) neutrophil population at the indicated peptide concentrations, and the percentage of necrotic versus apoptotic cells was determined by flow cytometry. The results are given as percent necrotic cells of the total number of cells (mean + SEM, n = 4; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). (C) The MPO-H2O2 system reverses the suppressive effect on neutrophils of the PSMα2 peptide. Neutrophils were incubated with buffer, nontreated PSMα2 peptide (1 μM), or peptide that was pretreated with MPO combined with H2O2. After 10 min at 37°C, the neutrophils were stimulated with PMA (50 nM) and the production of superoxide anion was recorded.

DISCUSSION

The new immunomodulatory functions for the cytotoxic PSMα peptides from CA-MRSA are in line with the suggestion that the PSMα peptides are important virulence determinants (50). We now show that the FPR2-specific formylated PSMα peptides activate neutrophils to produce ROS that, together with MPO, have the capacity to destroy the biological activities of the triggering peptides. Microbial toxins have earlier been shown to be inactivated by the MPO-H2O2 system (10, 11), and we now add the PSMα peptides to this group of MPO-H2O2-sensitive microbial virulence molecules. This inhibitory feedback loop puts the role of ROS production in modulation of innate immune reactions in focus, and the PSMs have two distinct functions in relation to the oxidase. On the one hand, the PSMs activate the oxidase and the ROS generated inactivate the peptide (a feedback inhibition phenomenon also seen with other chemoattractants); on the other hand, PSMs inhibit superoxide production induced by other stimuli, and it is clear that the inhibitory effect occurs without any involvement of the receptor FPR2.

The cytotoxic activity of the PSMs, affecting primarily apoptotic neutrophils, is also inhibited by the MPO-H2O2 system. The oxidation of functionally active methionine has been suggested to be the mechanism underlying loss of biological activity for bacterial compounds (10, 11, 20), and methionyl-containing chemoattractants lose biological activity following oxidation of this amino acid by the MPO-H2O2 system (12). The formylated methionyl has been regarded as a key residue for the interaction of microbial peptides with the classic formyl peptide receptor (FPR1) (34, 37), and it is fully logical that chemical alterations in this part of the molecule should affect the receptor-binding characteristics and by that the function of peptides that bind FPR2. With respect to the receptor involved, it is of special interest that the innate immune system senses peptide toxins through FPR2, a receptor earlier described to be primarily a target for new anti-inflammatory strategies (18, 39). The structural basis for PSMα inactivation is not known, but other critical amino acids (besides methionine) represent possible targets for oxidative inactivation. Further studies on the biochemical aspects of MPO-H2O2-mediated inactivation of these toxins should provide new knowledge into the precise structural properties of importance for their effects.

The generation of ROS by the phagocyte NADPH oxidase is a key element of the phagocyte weaponry against pathogens (45), but a growing body of evidence implies that oxygen radicals generated by the NADPH oxidase also have regulatory functions in immunity as well as autoimmunity (24, 36, 47, 48). Our data show that PSMα peptides can modulate the amount of ROS production in both FPR2-dependent and FPR2-indepedent manners. Recognition of PSMα peptides by FPR2 promotes the production of ROS, which in turn abrogate the biological activity of the peptides through oxidation. Additionally, PSMα peptides can interact with neutrophil functions independently of FPR2, possibly by affecting the membrane integrity in a way that prohibits proper assembly of the NADPH oxidase, and thereby downregulate ROS production in response to other proinflammatory stimuli. A functional NADPH oxidase can also be assembled at an internal membrane(s), resulting in superoxide ions being produced within an intracellular compartment (5). Pneumolysin produced from virulent strains of S. pneumoniae activates neutrophils to generate ROS in such a compartment (33) through a receptor-independent process most probably achieved through a direct interaction with cholesterol in the plasma membrane. The PSMα peptides evidently lack the ability to activate the oxidase by such a mechanism but trigger an extracellular release of superoxide anions through binding to FPR2.

Apparently, the PSMα peptides are capable of distinguishing between membranes with different compositions, and apoptotic neutrophils are more susceptible to membrane attacks from PSMα peptides than viable neutrophils. It should be noticed that the necrotic cells are very fragile, and when the experiments are performed at 37°C, they eventually lose their cellular integrity and by that are missed in subsequent FACS analysis. The apparent (but false) enrichment of viable cells is, thus, not due to a resurrection of necrotic cells (8). The process of secondary necrosis induces an uncontrolled release of potentially harmful neutrophil constituents. During the acute inflammatory phase of an infection, neutrophils are the predominant infiltrating cell type, and proper resolution of acute inflammation involves elimination of these cells after induction of apoptosis. That the PSMα peptides primarily target apoptotic neutrophils suggests a novel strategy whereby CA-MRSA could inhibit the resolution of inflammation.

During in vitro incubation, human neutrophils gradually change the composition of their membranes during apoptosis, and the differences relate both to the expression of various surface proteins and to their phospholipid compositions (31, 32). In vitro culture enables easy access to mixed-cell samples containing both viable and apoptotic cells; when added to such mixed-cell populations, the PSMα peptides selectively induced permeabilization primarily of apoptotic neutrophils, leaving the viable cells intact. This is not a unique property of the PSM peptides, but far from all amphipathic peptides show the same pattern of receptor-independent and selective permeabilization of apoptotic cells (2). We have earlier shown that neither the cationicity nor the α-helical structure of the peptide is sufficient for selective lysis of apoptotic cells and that there is no direct role for the increased exposure of anionic phosphatidylserine on the surface of apoptotic cells (2). An alternative explanation would be that the peptides interact similarly with apoptotic and viable membranes but that viable cells contain a variety of repair systems (not present or functional in apoptotic cells) able to rapidly restore the integrity of their membranes.

Our study corroborates the findings that formylated PSMα peptides from CA-MRSA bind and activate FPR2 and that this interaction leads to production and release of ROS from primary human neutrophils. Simultaneously with stimulating ROS release from neutrophils, the PSMα peptides also transferred cells to a viable but dysfunctional state where their responses to other ROS-releasing stimuli were potently suppressed. This inhibition of ROS production was, however, completely independent of FPR2. In addition, we show that the PSMα peptides displayed cytotoxic action against apoptotic neutrophils, again independently of FPR2, and the integrity of the neutrophils was rapidly destroyed. Furthermore, our report also shows that the ROS released from viable neutrophils react with the PSMα peptides and abolish their biological activities in a negative-feedback manner. These data add to the complexity by which CA-MRSA interacts with the innate immune system and could, hopefully, contribute to deciphering of the virulence of this emerging bacterial threat.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Swedish Medical Research Council, the King Gustaf the V 80-Year Foundation, the Swedish Society of Medicine, the IngaLill and Arne Lundberg foundation, and the Swedish Government under the ALF agreement.

We declare that no conflict of interest exists.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 19 March 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Betten A, et al. 2001. A proinflammatory peptide from Helicobacter pylori activates monocytes to induce lymphocyte dysfunction and apoptosis. J. Clin. Invest. 108:1221–1228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bjorstad A, et al. 2009. The host defense peptide LL-37 selectively permeabilizes apoptotic leukocytes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:1027–1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boyum A, Lovhaug D, Tresland L, Nordlie EM. 1991. Separation of leucocytes: improved cell purity by fine adjustments of gradient medium density and osmolality. Scand. J. Immunol. 34:697–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burton MF, Steel PG. 2009. The chemistry and biology of LL-37. Nat. Prod. Rep. 26:1572–1584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bylund J, Brown KL, Movitz C, Dahlgren C, Karlsson A. 2010. Intracellular generation of superoxide by the phagocyte NADPH oxidase: how, where, and what for? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 49:1834–1845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bylund J, et al. 2001. Proinflammatory activity of a cecropin-like antibacterial peptide from Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1700–1704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Christenson K, Bjorkman L, Tangemo C, Bylund J. 2008. Serum amyloid A inhibits apoptosis of human neutrophils via a P2X7-sensitive pathway independent of formyl peptide receptor-like 1. J. Leukoc. Biol. 83:139–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Christenson K, Thoren FB, Bylund J. 2012. Analyzing cell death events in cultured leukocytes. Methods Mol. Biol. 844:65–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clark RA. 1982. Chemotactic factors trigger their own oxidative inactivation by human neutrophils. J. Immunol. 129:2725–2728 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clark RA. 1986. Oxidative inactivation of pneumolysin by the myeloperoxidase system and stimulated human neutrophils. J. Immunol. 136:4617–4622 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Clark RA, Leidal KG, Taichman NS. 1986. Oxidative inactivation of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans leukotoxin by the neutrophil myeloperoxidase system. Infect. Immun. 53:252–256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clark RA, Szot S. 1982. Chemotactic factor inactivation by stimulated human neutrophils mediated by myeloperoxidase-catalyzed methionine oxidation. J. Immunol. 128:1507–1513 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cogen AL, et al. 2010. Selective antimicrobial action is provided by phenol-soluble modulins derived from Staphylococcus epidermidis, a normal resident of the skin. J. Invest. Dermatol. 130:192–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dahlgren C, et al. 2000. The synthetic chemoattractant Trp-Lys-Tyr-Met-Val-DMet activates neutrophils preferentially through the lipoxin A(4) receptor. Blood 95:1810–1818 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dahlgren C, Karlsson A. 1999. Respiratory burst in human neutrophils. J. Immunol. Methods 232:3–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dahlgren C, Karlsson A, Bylund J. 2007. Measurement of respiratory burst products generated by professional phagocytes. Methods Mol. Biol. 412:349–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Deleo FR, Otto M, Kreiswirth BN, Chambers HF. 2010. Community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 375:1557–1568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dufton N, Perretti M. 2010. Therapeutic anti-inflammatory potential of formyl-peptide receptor agonists. Pharmacol. Ther. 127:175–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Forsman H, Dahlgren C. 2010. The FPR2-induced rise in cytosolic calcium in human neutrophils relies on an emptying of intracellular calcium stores and is inhibited by a gelsolin-derived PIP2-binding peptide. BMC Cell Biol. 11:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Forsman H, et al. 2008. The beta-galactoside binding immunomodulatory lectin galectin-3 reverses the desensitized state induced in neutrophils by the chemotactic peptide f-Met-Leu-Phe: role of reactive oxygen species generated by the NADPH-oxidase and inactivation of the agonist. Glycobiology 18:905–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fu H, et al. 2004. The two neutrophil members of the formylpeptide receptor family activate the NADPH-oxidase through signals that differ in sensitivity to a gelsolin derived phosphoinositide-binding peptide. BMC Cell Biol. 5:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21a. Forsman H, Onnheim K, Andreasson E, Dahlgren C. 2011. What formyl peptide receptors, if any, are triggered by compound 43 and lipoxin A4?. Scand. J. Immunol. 74:227–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fu H, Bjorstad A, Dahlgren C, Bylund J. 2004. A bactericidal cecropin-A peptide with a stabilized alpha-helical structure possess an increased killing capacity but no proinflammatory activity. Inflammation 28:337–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fu H, et al. 2006. Ligand recognition and activation of formyl peptide receptors in neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 79:247–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gelderman KA, et al. 2007. Macrophages suppress T cell responses and arthritis development in mice by producing reactive oxygen species. J. Clin. Invest. 117:3020–3028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Graves SF, Kobayashi SD, DeLeo FR. 2010. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus immune evasion and virulence. J. Mol. Med. (Berl.) 88:109–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Karlsson J, et al. 2009. The FPR2-specific ligand MMK-1 activates the neutrophil NADPH-oxidase, but triggers no unique pathway for opening of plasma membrane calcium channels. Cell Calcium 45:431–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kobayashi SD, DeLeo FR. 2009. An update on community-associated MRSA virulence. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 9:545–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kretschmer D, et al. 2010. Human formyl peptide receptor 2 senses highly pathogenic Staphylococcus aureus. Cell Host Microbe 7:463–473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu L, et al. 1998. Desensitization of formyl peptide receptors is abolished in calcium ionophore-primed neutrophils: an association of the ligand-receptor complex to the cytoskeleton is not required for a rapid termination of the NADPH-oxidase response. J. Immunol. 160:2463–2468 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Makgotlho PE, et al. 2009. Molecular identification and genotyping of MRSA isolates. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 57:104–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Martin SJ, et al. 1995. p34cdc2 and apoptosis. Science 269:106–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Martin SJ, et al. 1995. Early redistribution of plasma membrane phosphatidylserine is a general feature of apoptosis regardless of the initiating stimulus: inhibition by overexpression of Bcl-2 and Abl. J. Exp. Med. 182:1545–1556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Martner A, Dahlgren C, Paton JC, Wold AE. 2008. Pneumolysin released during Streptococcus pneumoniae autolysis is a potent activator of intracellular oxygen radical production in neutrophils. Infect. Immun. 76:4079–4087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Miettinen HM, et al. 1997. The ligand binding site of the formyl peptide receptor maps in the transmembrane region. J. Immunol. 159:4045–4054 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Migeotte I, Communi D, Parmentier M. 2006. Formyl peptide receptors: a promiscuous subfamily of G protein-coupled receptors controlling immune responses. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 17:501–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mossberg N, et al. 2007. Oxygen radical production and severity of the Guillain-Barre syndrome. J. Neuroimmunol. 192:186–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Movitz C, Brive L, Hellstrand K, Rabiet MJ, Dahlgren C. 2010. The annexin I sequence gln(9)-ala(10)-trp(11)-phe(12) is a core structure for interaction with the formyl peptide receptor 1. J. Biol. Chem. 285:14338–14345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Otto M. 2010. Basis of virulence in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 64:143–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Perretti M, D'Acquisto F. 2009. Annexin A1 and glucocorticoids as effectors of the resolution of inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9:62–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Prat C, et al. 2009. A homolog of formyl peptide receptor-like 1 (FPRL1) inhibitor from Staphylococcus aureus (FPRL1 inhibitory protein) that inhibits FPRL1 and FPR. J. Immunol. 183:6569–6578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rabiet MJ, Huet E, Boulay F. 2005. Human mitochondria-derived N-formylated peptides are novel agonists equally active on FPR and FPRL1, while Listeria monocytogenes-derived peptides preferentially activate FPR. Eur. J. Immunol. 35:2486–2495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rabiet MJ, Huet E, Boulay F. 2007. The N-formyl peptide receptors and the anaphylatoxin C5a receptors: an overview. Biochimie 89:1089–1106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rautenberg M, Joo HS, Otto M, Peschel A. 2011. Neutrophil responses to staphylococcal pathogens and commensals via the formyl peptide receptor 2 relates to phenol-soluble modulin release and virulence. FASEB J. 25:1254–1263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schlievert PM, Strandberg KL, Lin YC, Peterson ML, Leung DY. 2010. Secreted virulence factor comparison between methicillin-resistant and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, and its relevance to atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 125:39–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Segal BH, Veys P, Malech H, Cowan MJ. 2011. Chronic granulomatous disease: lessons from a rare disorder. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 17:S123–S131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stenfeldt AL, et al. 2007. Cyclosporin H, Boc-MLF and Boc-FLFLF are antagonists that preferentially inhibit activity triggered through the formyl peptide receptor. Inflammation 30:224–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Thoren FB, Romero AI, Hellstrand K. 2006. Oxygen radicals induce poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-dependent cell death in cytotoxic lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 176:7301–7307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Thoren FB, Romero AI, Hermodsson S, Hellstrand K. 2007. The CD16-/CD56bright subset of NK cells is resistant to oxidant-induced cell death. J. Immunol. 179:781–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tristan A, et al. 2007. Virulence determinants in community and hospital meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Hosp. Infect. 65(Suppl. 2):105–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wang R, et al. 2007. Identification of novel cytolytic peptides as key virulence determinants for community-associated MRSA. Nat. Med. 13:1510–1514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ye RD, et al. 2009. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXIII. Nomenclature for the formyl peptide receptor (FPR) family. Pharmacol. Rev. 61:119–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhang Z, Cherryholmes G, Shively JE. 2008. Neutrophil secondary necrosis is induced by LL-37 derived from cathelicidin. J. Leukoc. Biol. 84:780–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.