Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus is a leading cause of severe endophthalmitis, which often results in vision loss in some patients. Previously, we showed that Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) ligand pretreatment prevented the development of staphylococcal endophthalmitis in mice and suggested that microglia might be involved in this protective effect (Kumar A, Singh CN, Glybina IV, Mahmoud TH, Yu FS. J. Infect. Dis. 201:255–263, 2010). The aim of the present study was to understand how microglial innate response is modulated by TLR2 ligand pretreatment. Here, we demonstrate that S. aureus infection increased the CD11b+ CD45+ microglial/macrophage population in the C57BL/6 mouse retina. Using cultured primary retinal microglia and a murine microglial cell line (BV-2), we found that these cells express TLR2 and that its expression is increased upon stimulation with bacteria or an exclusive TLR2 ligand, Pam3Cys. Furthermore, challenge of primary retinal microglia with S. aureus and its cell wall components peptidoglycan (PGN) and lipoteichoic acid (LTA) induced the secretion of proinflammatory mediators (tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α] and MIP-2). This innate response was attenuated by a function-blocking anti-TLR2 antibody or by small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown of TLR2. In order to assess the modulation of the innate response, microglia were pretreated with a low dose (0.1 or 1 μg/ml) of Pam3Cys and then challenged with live S. aureus. Our data showed that S. aureus-induced production of proinflammatory mediators is dramatically reduced in pretreated microglia. Importantly, microglia pretreated with the TLR2 agonist phagocytosed significantly more bacteria than unstimulated cells. Together, our data suggest that TLR2 plays an important role in retinal microglial innate response to S. aureus, and its sensitization inhibits inflammatory response while enhancing phagocytic activity.

INTRODUCTION

Bacterial endophthalmitis is a rare but extremely serious complication of intraocular surgeries frequently leading to blindness and visual disability. While the pathogenesis of bacterial endophthalmitis is not fully understood, it starts with the introduction of bacteria into the posterior segment of the eye either during ocular surgeries or by penetrating eye injuries (5), and occasionally via hematogenous spread of the organism to the eye (44). Once the bacteria are in the vitreous cavity, they rapidly proliferate and initiate an inflammatory response, resulting in the breakdown of the blood-ocular barrier (42) and increased inflammatory cell recruitment (6). The mechanisms of pathogen recognition and initiation of innate defense in this disease are not well understood but are presumed to involve retinal glial cells. Among the potential retinal glial cells involved in antimicrobial defense are microglia, which represent the resident mononuclear phagocyte population present in the central nervous system (CNS) (9). These cells share many phenotypic and functional characteristics with macrophages (60) and are uniquely poised to provide the first line of defense against invading pathogens, even prior to leukocyte infiltration. In order to accomplish this task, microglia express a vast repertoire of microbial pattern recognition receptors, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and phagocytic receptors, which collectively function to detect and eliminate invading microbes (25, 53). In addition, microglial activation elicits a broad range of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines that are involved in the recruitment and subsequent activation of peripheral immune cells infiltrating the injured or infected CNS or the retina (1, 13, 35, 51).

Although the production of proinflammatory cytokines is important for mediating the initial host defense against invading pathogens, an excessive inflammatory response can be detrimental to the host. Thus, TLR-mediated inflammation is a double-edged sword that must be precisely regulated (11). One of the unique features of TLR signaling is the development of tolerance by initial priming with a small amount of the ligand (3). The priming event leads to the suppression and redirection of the subsequent response to stimulation with a secondary TLR ligand. Such tolerance is associated with impaired NF-κB cell signaling and suppressed proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine production (30, 39). Thus, ligand-induced tolerance may represent a negative feedback mechanism invoked to induce inflammation resolution and restore homeostasis after TLR activation (28). Preconditioning of animals to TLR ligands such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (32, 50, 56), bacterial lipoproteins (7, 16, 34), and flagellin (27, 28, 58) has been shown to provide protection against infection and sepsis in animal models. The retina is extremely sensitive to inflammation-mediated damage (60). Thus, it is of paramount importance to identify ways to enhance the innate defenses in the retina while reducing or avoiding inflammation-induced pathology during infection. Along these lines, we have shown that exogenous administration of TLR ligands in small doses before bacterial inoculation, at least for TLR2, provides protection against bacterial endophthalmitis (29).

Since TLR2 was implicated as a major receptor for recognition of S. aureus, and microglia were found to express TLR2, we postulated that preconditioning may alter the innate response of microglia. We tested this hypothesis by comparing the innate response to S. aureus challenge of microglia preconditioned with TLR2 ligand to that of microglia without preconditioning. Our data showed that microglia are activated in response to S. aureus challenge in vivo, and TLR2 ligand pretreatment diminished their inflammatory response to S. aureus in vitro. Interestingly, TLR2 ligand enhanced the phagocytic activity of retinal microglia. Thus, modulating the retinal innate response via TLR signaling could provide new approaches for reducing the incidence of bacterial endophthalmitis without causing retinal damage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strain and reagents.

Staphylococcus aureus (RN 6390) was maintained in tryptic soy broth (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Before infection, bacteria were cultured in tryptic soy broth overnight, and the optical density (OD) was adjusted to 0.5 using a spectrophotometer. For the in vivo experiment, S. aureus expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) (AL 1743) was used. The bacterial lipopeptide Pam3Cys-Ser-(Lys)4 hydrochloride (Pam3Cys), a synthetic lipopeptide that acts as a TLR2 agonist, was purchased from Invivogen, (San Diego, CA). Monoclonal antibody (MAb) against phospho-p38 MAPK (catalogue no. 9211; 43 kDa), anti-p38 antibody (catalogue no. 9212; 43 kDa), anti-phospho-IκB-α antibody (catalogue no. 9246; 40 kDa), anti-IκB-α antibody (catalogue no. 9242; 39 kDa), anti-TLR2 antibody (catalogue no. 2229; 95 kDa), and Hsp-90 antibody (catalogue no. 4874; 90 kDa) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Phenol-extracted, purified S. aureus lipoteichoic acid (LTA) was kindly provided by Siegfried Morath (University of Konstanz, Constance, Germany). S. aureus peptidoglycan (PGN) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and this preparation has been shown to contain <0.0025 ng/mg endotoxin while being insensitive to polymyxin B (binding to and inhibiting LPS) (31).

Cell culture.

Mouse primary retinal microglia were isolated from the eyes of 2- to 3-day-old C57BL/6 mouse pups. Animals were euthanized and their eyes enucleated. The globes were dissected and rinsed with Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS), transferred into 2% dispase, and placed in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C for 1 h. Dispase activity was neutralized by washing the globes with low-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (HyClone, South Logan, UT) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serium (FBS) (BioAbchem, Ladson, SC). The anterior segment and vitreous were excised, and the retinal pigment epithelium layer was removed. The retinas were transferred into DMEM containing 10% FBS and triturated several times with a pipette. The dissociated cells were transferred into 75-cm2 flasks and left to grow at 37°C. After the mixed culture had grown confluent, microglia were detached by mechanical shaking. The detached cells, comprising 90% microglia, were then cultured in 100-mm dishes at low density. Each microglial cell divided over the next 3 weeks to form individual colonies of adherent cells. Individual cell clusters, comprising solely microglia, were trypsinized inside a colony cylinder and cultured in a new 75-cm2 flask. Microglia were identified by their branching morphology and positive Iba-1 staining. The purity of microglia in this resulting culture exceeded 98%. Both primary and brain-derived BV-2 microglia (kindly provided by David Thomas, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Wayne State University) were maintained in low-glucose DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS and a penicillin-streptomycin cocktail (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. Before treatment, cells were cultured in antibiotic-free and serum-free DMEM for 18 h (growth factor starvation). At the time of treatment, the cell culture medium was replaced with fresh antibiotic and serum-free DMEM.

Western blot analysis.

BV-2 microglia challenged with either Pam3Cys-Ser-(Lys)4 or S. aureus RN6390 were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer [150 mM NaCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1% deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 1% Triton X-100, 50 mM NaF, 100 mm sodium pyrophosphate, and 3.5 mM sodium orthovanadate]. A protease inhibitor cocktail containing aprotinin, pepstatin A, leupeptin, and antipain (1 mg/ml each), and 0.1 M phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the RIPA buffer before use (1 μl/ml). The protein concentration of cell lysates was determined by bicinchoninic assay (MicroBCA; Pierce). Samples were prepared with 30 μg protein and 10 μl SDS sample buffer. Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) in Tris-glycine-SDS buffer (25 mM Tris, 250 mM glycine, and 0.1% SDS) and electroblotted onto 0.45-μm nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). After blocking for 1 h in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST; 20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.05% Tween) containing 5% nonfat milk, the blots were probed with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The membranes were washed three times with TBST (pH 7.6) and incubated in TBST containing 5% nonfat milk with 1:2,000 dilutions of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Bio-Rad) for 60 min at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized with Supersignal chemiluminescent reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Microglial secretion of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and MIP-2 was assessed by ELISA. Cells were plated at 1 × 106 cells/per well in a six-well dish. After growth factor starvation, cells were pretreated with Pam3Cys or left untreated and further challenged with either a high dose of Pam3Cys or S. aureus. At the desired time points, culture medium was harvested, centrifuged, and used for measurement of cytokines. The ELISA was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The amount of cytokines secreted into the cultured medium was measured in nanograms per milliliter (ng/ml). All values are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD).

Conventional and real-time RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from microglia using TRIzol solution (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and 2 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed with a first-strand synthesis system for reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) (SuperScript; Invitrogen). cDNA was further amplified using primers for mouse TNF-α, MIP-2, TLR-1, TLR2, TLR-4, TLR-6, and GAPDH (Table 1). The PCR products and internal control GAPDH were subjected to electrophoresis on 1.2% agarose gels containing ethidium bromide. Stained gels were captured by a digital camera (EDAS 290 system; Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). Quantitative assessment of gene expression was carried out by TaqMan probe-based real-time PCR using predesigned assays (IDT, Coralville, IA) on a StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The data were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

Table 1.

Sequences and product sizes of PCR primers

| Gene product | Primer sequencea | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| TLR1 | F: GTTGTCACTGATGTCTTCAGC | 319 |

| R: CTGTACCTTAGAGAATTCTG | ||

| TLR2 | F: TGCTTTCCTGCTGGAGATTT | 196 |

| R: TGTAACGCAACAGCTCAGG | ||

| TLR4 | F: TTGTCTTCTGCACGAACCTG | 311 |

| R: GGCAACGCAAGGATTTTATT | ||

| TLR6 | F: AGTGCTGCCAAGTTCCGACA | 527 |

| R: AGCAAACACCGAGTATAGCG | ||

| TNF-α | F: GACCCTCACACTCAGATCAT | 307 |

| R: TTGAAGAGAACCTGGGAGTA | ||

| MIP-2 | F: TGTCATGCCTGAAGACCTGCC | 152 |

| R: AACTTTTTGACCGCCCTTGAGAGTGG | ||

| CD11b | F: CAGATCAACAATGTGACCGTATGGG | 497 |

| R: CATCATGTCCTTGTACTGCCGCTTG | ||

| GAPDH | F: TCATTGACCTCAACTACATGGT | 442 |

| R: CTAAGCAGTTGGTGGTGCAG |

The annealing temperature was 55°C for all primers. F, forward; R, reverse.

S. aureus endophthalmitis model.

To experimentally induce bacterial endophthalmitis, eyes from C57BL/6 mice (8 weeks old) were intravitreally injected with 1 μl sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing either 5,000 CFU of S. aureus (strain RN6390 or ALC1743) or PBS alone as a control. The injections were made in the midvitreous of the left eyes using a 34-gauge needle (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). The right eye of each mouse was left untreated or uninfected and served as an internal control. At the desired time points, inoculated eyes were subjected to cryosectioning, histology, or flow cytometry. Mice were treated in compliance with the ARVO statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research, and all procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Wayne State University.

Immunofluorescence staining.

Retinal cryosections were rinsed in PBS and blocked for 1 h in blocking buffer [10% (vol/vol) normal goat serum, 0.3% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 in PBS] at room temperature. The slides were then incubated overnight with Iba-1 (Dako, Denmark), CD11b, or TLR-2 (Santa Cruz, CA) antibodies at 4°C. Following removal of the primary antibodies, the slides were extensively washed and incubated for 1 h in fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated secondary antibodies (FITC–anti-rabbit IgG) at room temperature. After several washing steps in PBS, the slides were mounted in Vectashield antifade mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and visualized using a confocal system (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Immunohistochemistry and GFP tagging.

At desired time points, eyes from mice infected with GFP-expressing S. aureus (ALC 1743) were enucleated. Cryosections were subjected to direct fluorescence microscopy (Olympus) after mounting with Vectashield mounting medium with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). For GFP tagging, eyes were kept overnight in fixative (Excalibur Pathology Inc., Oklahoma City, OK) followed by paraffin embedding. To detect GFP immunoreactivity, sections were deparaffinized and incubated with rabbit anti-GFP antibody (Invitrogen; catalog no. A11122) overnight at 4°C, followed by detection using rabbit ImmPress and a 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AEC) peroxidase substrate (Vector Laboratories). Hematoxylin was used for counterstaining.

Flow cytometry analysis.

For in vitro studies, Pam3Cys- or S. aureus-challenged primary and BV-2 microglia were dispensed into Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged at 100 × g at 4°C for 5 min. Cells were resuspended in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin followed by blocking in 10% serum for 30 min at room temperature. Next, the cells were washed, resuspended in PBS containing anti-TLR2 antibody or isotype-matched IgG (1:100 dilution), and incubated overnight at 4°C. Cells were then washed and incubated for 1 h with the corresponding secondary FITC-conjugated antibody. A FACScan flow cytometer (BD Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA) was used for cytometric analysis.

For in vivo studies, C57BL/6 mice were challenged with S. aureus (RN6390; 5,000 CFU/eye) by intravitreal injections. Uninjected mice or those injected with PBS were used as controls. The retinas were removed from the eyes as described by Skeie et al. (52) and were digested in Accumax (Millipore, Billerica, MA) for 10 min at 37°C. Retinas from two eyes were pooled to obtain a sufficient number of cells. Following digestion, the retinal tissue was passed three or four times through a 23-gauge needle or syringe and filtered through a 40-μm cell strainer (BD Falcon). The cells were incubated with Fc Block (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA) for 30 min, followed by a washing step with PBS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Cells were then incubated with the phycoerythrin (PE)- and Cy5 conjugated CD45, CD11b-FITC, and TLR2-PE MAbs and the respective isotypes (BD Pharmingen) for 30 min in the dark. After a washing step, the cells were acquired on a BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Immunocytometry Systems), and the data were analyzed using FlowJo (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR).

Phagocytosis assay.

Both primary and BV-2 microglia (105 cells per well) were seeded onto 12-well plates in DMEM without antibiotics and allowed to grow at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 1 day followed by Pam3Cys (0.1 μg/ml) challenge for 24 h. One hour prior to the experiments, cells were washed three times with PBS, and 1 ml of DMEM medium containing S. aureus was added at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10:1 to each well. After 1 h of incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, cells were washed three times with PBS, and 1 ml of medium containing gentamicin (200 μg/ml) was added to each well to lyse extracellular and adherent bacteria. The absence of extracellular bacteria was then confirmed by CFU enumeration on agar plates. For enumeration of phagocytosed bacteria, after 2 h, wells were washed three times with PBS, incubated with 500 μl of 0.01% Triton X-100 in PBS to release intracellular bacteria, and then plated on Trypticase soy agar for determination of the CFU.

RESULTS

S. aureus infection increases the CD45+ CD11b+ retinal microglia/macrophage population.

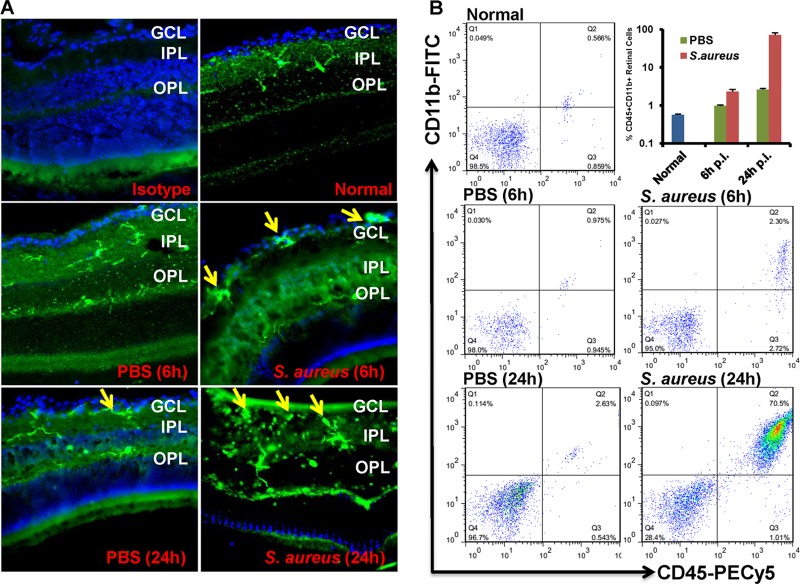

Microglia are the resident macrophage population in the central nervous system (CNS); thus, they are involved in initiating early innate defense against invading pathogens (38). To test if the retinal microglia are activated in response to bacterial infection, as it occurs in the brain, mice were given intravitreal injections of S. aureus (5,000 CFU/eye), and eyes were enucleated at 6 and 24 h postinfection to investigate the distribution of retinal microglia. In the uninjected and PBS-injected control eyes, Iba-1 (microglial marker)-positive cells were mainly present in inner (IPL) and outer (OPL) plexiform layers. In contrast, increased numbers of Iba-1 positive cells were localized in the ganglion cell layer (GCL) in infected eyes (Fig. 1A). To assess the activation and recruitment of retinal microglia, retinas were subjected to flow cytometry analysis. Compared to their relative PBS-injected controls, the proportion of CD45+ CD11b+ retinal cells (microglia/macrophages) was significantly increased in S. aureus-challenged eyes at 6 h (0.9% versus 2.3%) and 24 h (2.6% versus 70%) postinfection (Fig. 1B).

Fig 1.

S. aureus infection increased the proportion of CD45+ CD11b+ retinal microglia/macrophages. (A) C57BL/6 mice were given intravitreal injections of PBS or 5,000 CFU of S. aureus. At the indicated time points, eyes were enucleated and embedded in OCT, and cryosections were stained with rabbit monoclonal anti-Iba-1 antibody. (B) For flow cytometry analysis, pooled single-cell suspensions from two retinas were stained with isotype control or with anti-CD45 and anti-CD11b MAbs. Postacquisition, the cells were size gated to differentiate them from debris. The percentage of dually positive retinal microglia was then determined using a CD45-versus-CD11b dot plot (upper right [Q2] quadrant). The data are representative of duplicate experiments. GCL, ganglion cell layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer.

Retinal microglia express TLR2, and its expression is increased upon activation.

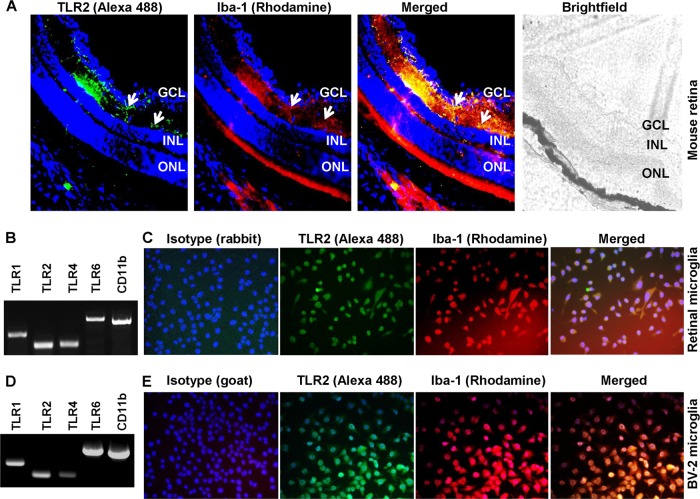

To understand how retinal microglia recognize S. aureus, we assessed the role of TLRs in this process. TLR2 and its coreceptors TLR1 and -6 are known to play an important role in the initiation of the innate response against Gram-positive bacteria, including S. aureus (43, 54), whereas TLR4 is a major receptor implicated in recognizing Gram-negative bacteria (55). To determine whether these receptors are expressed in retinal microglia in vivo, immunostaining was performed on mouse retinal sections. As shown in Fig. 2A, TLR2 expression colocalizes with Iba-1-positive cells, an indication of their microglial source. To further characterize TLR expression, we performed RT-PCR on cultured primary retinal microglia and showed that these cells constitutively express TLR1, -2, -4, and -6 and microglial marker CD11b mRNA (Fig. 2B). To confirm these results, we used the known mouse microglial cell line BV-2, and as reported previously (35, 59), these cells also expressed these TLRs (Fig. 2D). To provide further evidence of TLR expression, we performed immunohistochemistry and showed that TLR2 protein is expressed in Iba-1-positive primary retinal (Fig. 2C) and BV-2 (Fig. 2E) microglial cells.

Fig 2.

Mouse retinal microglia express Toll-like receptor 2. (A) Cryosections (inferior medial) of C57BL/6 mouse retina were stained with specific antibodies to TLR2 (green) and Iba-1 (red), a marker for microglial cells. Immunolabeling of TLR2 was localized to retinal microglia (arrows). (B and D) Total RNA extracted from primary retinal microglia (B) and BV-2 microglia (D) was subjected to RT-PCR analysis of expression of TLR1, -2, -4, and -6 and the microglial marker CD11b. (C and E) Primary retinal (C) and BV-2 (E) microglia were cultured on glass chamber slides and stained with TLR2 and Iba-1antibodies, and colocalization was performed. The specificity of the TLR2 (rabbit anti-mouse TLR2) and Iba-1 (goat anti-mouse Iba-1) antibodies was determined by using respective isotypes. GCL, ganglion cell layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer.

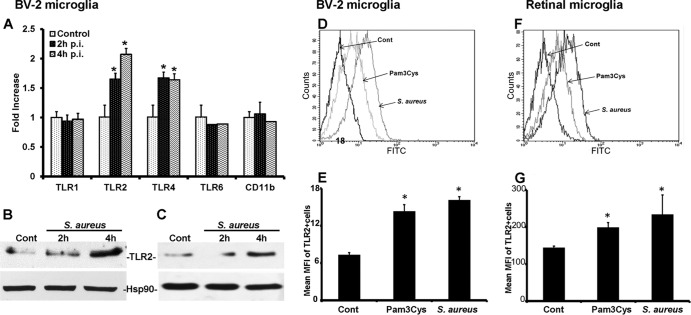

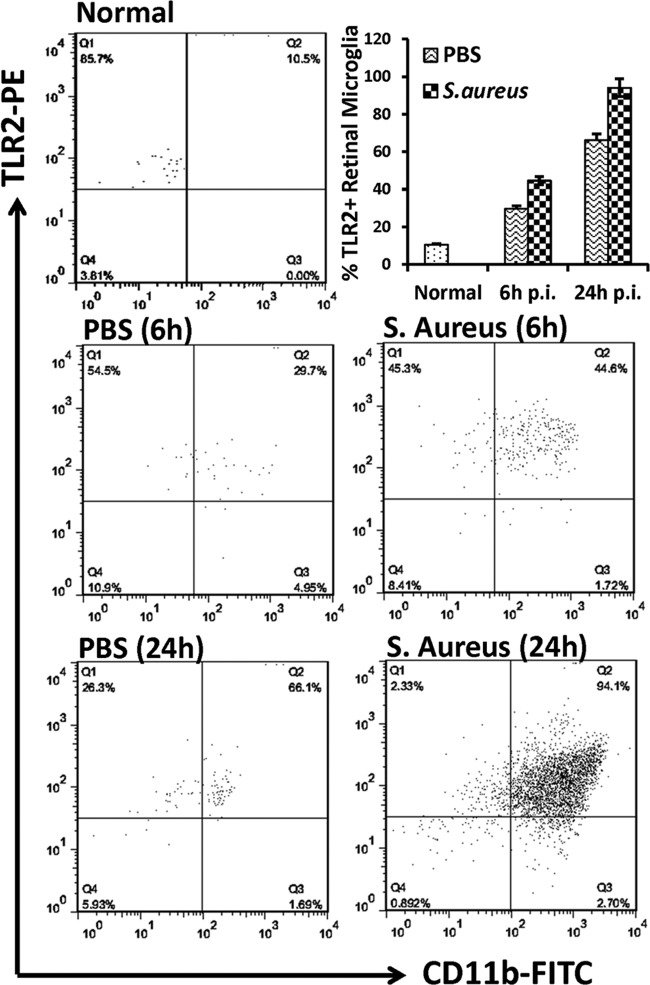

Since both primary retinal and BV-2 microglia were found to express TLRs, we next investigated whether their expression is modulated by S. aureus challenge. The real-time RT-PCR analysis was performed on the BV-2 microglial cell line. Compared to the control (untreated) cells, the expression of TLR2 and -4 mRNA was increased in S. aureus-stimulated cells 4 h postinfection (p.i.) (Fig. 3A), and this difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05). In contrast, the expression levels of TLR1, TLR6, and CD11b did not change significantly. The induced expression of TLR2 at the protein level was confirmed in both BV-2 (Fig. 3B) and primary (Fig. 3C) microglia by Western blotting. To provide further evidence of induced TLR2 expression, we also performed flow cytometry, which showed that both Pam3Cys and S. aureus stimulation augmented TLR2 expression in both BV-2 (Fig. 3D and E) and primary (Fig. 3F and G) retinal microglia. To determine whether, similar to the findings in in vitro studies, TLR2 expression is modulated on retinal microglia in vivo, we performed flow cytometry analysis on the mouse retina. In response to S. aureus infection, increased TLR2 expression was detected on CD45+ CD11b+ cells (Fig. 4).

Fig 3.

S. aureus and Pam3Cys upregulate TLR2 expression in cultured retinal microglia. (A) BV-2 cells were challenged with S. aureus for the indicated times. Real-time RT-PCR analysis was performed for expression of various TLRs and CD11b. The data are presented as fold increase by using a value of 1 for the ratio of the control value to that for the GAPDH sample. (B and C) Induced TLR2 expression in BV-2 (B) and primary (C) microglia was further confirmed by Western blotting of lysates from cells that had been challenged with S. aureus for the indicated times. (D through G) To analyze cell surface expression of TLR2, BV-2 (D and E) or primary retinal (F and G) microglia challenged with Pam3Cys (10 μg/ml) or S. aureus for 6 h were stained for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis, and data are presented as mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of TLR2-positive BV-2 (E) or primary (G) cells. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test, and data for S. aureus- and Pam3Cys-challenged cells were significantly different from those for unstimulated controls (*, P < 0.05).

Fig 4.

S. aureus enhanced TLR2 expression on CD45+ CD11b+ retinal microglia/macrophages in vivo. Eyes of C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with S. aureus (5,000 CFU) by intravitreal injection, and the retinas were isolated 6 h and 24 h p.i. Retinas from PBS-injected or uninjected (normal) eyes were used as controls. Following digestion with Accutase, single-cell suspensions from two retinas were pooled and stained with isotype control or with anti-TLR2, -CD45, and -CD11b MAbs. Postacquisition, CD45+ CD11b+ retinal microglia were evaluated for TLR2 expression on a CD11b-versus-TLR2 dot plot (upper right [Q2] quadrant).

Retinal microglial innate response to S. aureus and its cell wall component is TLR2 dependent.

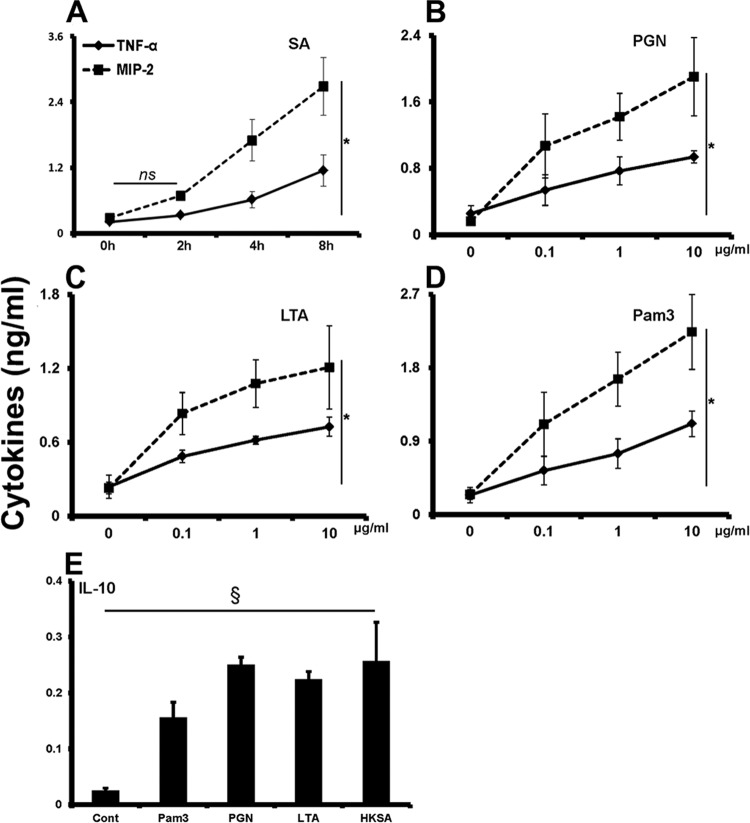

The hallmark of TLR activation is the production of inflammatory mediators (41). Thus, to assess the function of expressed TLRs on retinal microglia, we first tested whether they were responsive to S. aureus challenge. As shown in Fig. 5A, S. aureus challenge induced the production of inflammatory mediators TNF-α and MIP-2 in primary retinal microglia. Moreover, the response is time dependent, as increased levels of cytokines were detected at the 8-h time point. Having observed the secretion of cytokines from S. aureus-infected microglia, we then examined which bacterial cell wall components are responsible for this innate response. To do this, retinal microglial cells were challenged with peptidoglycan (PGN), lipoteichoic acid (LTA), and an exclusive TLR2 ligand, Pam3Cys. Similar to bacterial challenge, PGN (Fig. 5B), LTA (Fig. 5C), and Pam3 (Fig. 5D) challenges induced the production of TNF-α and MIP-2 in a concentration-dependent manner. In addition to secreting proinflammatory mediators, microglia are known to express immunosuppressive cytokines. In this regard, our data showed that 24-h stimulation of retinal microglia by heat-killed S. aureus (HKSA) and its cell wall components induced the secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin 10 (IL-10) (Fig. 5E).

Fig 5.

S. aureus and its cell wall components induce pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine secretion in primary retinal microglia. (A through D) Primary retinal microglia were stimulated with live S. aureus (SA) (A), the cell wall component peptidoglycan (PGN) (B) or lipoteichoic acid (LTA) (C), or an exclusive TLR2 ligand, Pam3Cys (D), for 4 h. At the end of the incubation period, culture supernatants were collected, and MIP-2 or TNF-α level were quantitated by ELISA. (E) The secretion of IL-10 was detected in microglia challenged with a higher (10 μg/ml) concentration of indicated cell wall components or heat-killed S. aureus (HKSA) for 24 h. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way (§, P < 0.05) and two-way (*, P < 0.05) ANOVA, and indicated statistical significances are for comparisons of cytokine secretion in control versus stimulated cells. Data points and bars are means ± SD of triplicate observations, each conducted twice independently. ns, not significant.

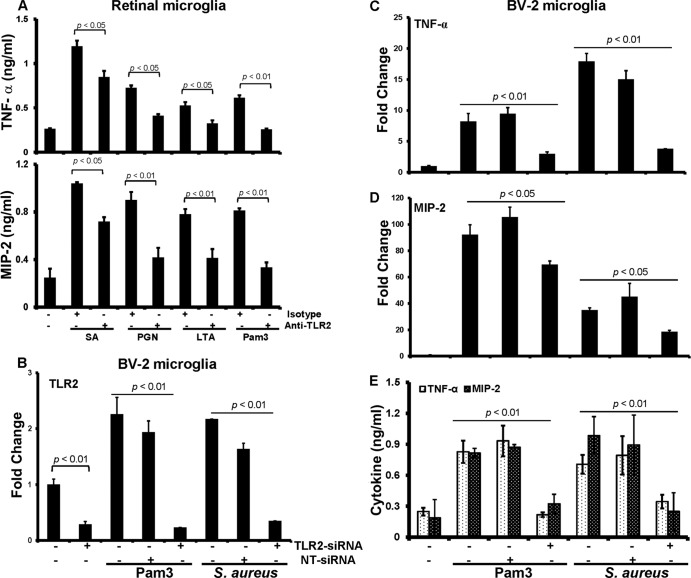

Next, we determined whether TLR2 is required for this response. In the presence of the function-blocking anti-TLR2 Ab, the production of TNF-α was reduced ∼35% in cells challenged with live S. aureus. Similarly, anti-TLR2 antibody treatment attenuated the production of TNF-α in response to PGN (45%) and LTA (50%) challenge, and as expected, the response to Pam3Cys was almost completely blocked (Fig. 6A). A similar inhibition pattern was observed for MIP-2 (Fig. 6A). In addition to antibody-mediated inhibition of TLR2 signaling, we also used the small interfering RNA (siRNA) approach to knock down TLR2 expression. As shown in Fig. 6B, the siRNA treatment led to significant (71%) reduction of TLR2 expression in control BV-2 cells. Most importantly, the expression of TLR2 remained low even upon stimulation with Pam3Cys or S. aureus in siRNA-treated cells compared to scrambled nontargeted siRNA (NT-siRNA)-transfected or nontransfected cells. Consistent with reduced TLR2 expression, siRNA-transfected cells expressed reduced levels of TNF-α (Fig. 6C) and MIP-2 (Fig. 6D) mRNA and protein (Fig. 6E) compared to nontransfected and NT-siRNA controls. Taken together, these findings are in agreement with the facts that S. aureus cell wall components induce an inflammatory response in microglia and that TLR2 plays a role in their recognition.

Fig 6.

S. aureus-induced microglial inflammatory response is attenuated by inhibition of TLR2 signaling. (A) Primary retinal microglia were pretreated for 1 h with isotype (10 μg/ml) or anti-TLR2 (10 μg/ml) antibodies followed by challenge with live S. aureus (SA) or the indicated ligands. After 4 h of stimulation culture supernatants were collected and TNF-αand MIP-2 levels were quantitated by ELISA. (B through E) For siRNA transfection, BV-2 cells were transfected with nontargeted siRNA (NT-siRNA) or TLR2-siRNA for 48 h, followed by challenge with Pam3Cys or S. aureus for 4 h. At the end of incubation of period cells were used for RNA extraction followed by real-time RT-PCR analysis to access the knockdown of the genes for TLR2 (B) and the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α (C) and MIP-2 (D), whereas culture medium was used to assess their secretion by ELISA (E). Data are means ± SD of triplicate cultures and are representative of three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test, and statistical significances for comparisons of cells treated with isotype versus anti-TLR2 antibody and NT-siRNA versus TLR2-siRNA are shown. For multiple-group comparison, one- or two-way ANOVA was used.

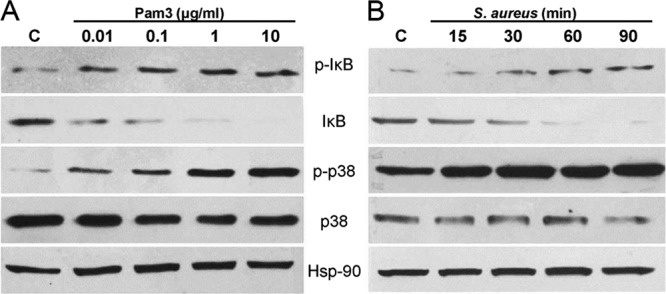

S. aureus and Pam3Cys induce NF-κB and p38 MAPK signaling in microglia.

TLR-mediated production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines is regulated by downstream NF-κB and MAPK signaling. To assess whether these signaling pathways were activated, we first challenged the BV-2 microglia with increasing concentrations of Pam3Cys. This showed that these cells were responsive to Pam3Cys at a concentration as low as 0.01 μg/ml, as detected by Western blot analysis of IκB-α phosphorylation, an indicator of NF-κB activation. Treatment of cells with 1 or 10 μg/ml Pam3Cys resulted in the maximum phosphorylation of IκB-α (Fig. 7A). A similar concentration-dependent trend was observed with the phosphorylation of p38, a member of the MAPK family.

Fig 7.

S. aureus and Pam3cys elicit the activation of NF-κB and p38 MAPK signaling in microglia. BV-2 microglia were stimulated with increasing concentrations of Pam3Cys (A) or live S. aureus (B) for the indicated time points. The cells were lysed for Western blot analysis using antibodies against phospho-IκB-α (p-IκB) and phospho-p38 (p-p38). Antibodies against nonphosphorylated IκB and p38 were used to detect their total levels, and Hsp-90 was used as an equal protein loading control. BV-2 cells challenged with Pam3Cys or SA showed significant activation of NF-κB and p-38 signaling pathways, in a concentration- and time-dependent manner. The data are representative of duplicate experiments.

Time course studies of the microglial response to S. aureus were also performed. Microglial cells stimulated with live S. aureus resulted in IκB-α phosphorylation detectable at 30 min, and levels remained elevated at 90 min poststimulation (Fig. 7B). Accompanying the increase in IκB-α phosphorylation, IκB degradation was observed 30 min poststimulation and was maximized at 90 min. The time course of p38 phosphorylation was similar to that of IκB-α, with maximum activation detected 90 min after stimulation. Thus, these findings demonstrate that TLR2 ligand and S. aureus stimulation of microglia induces phosphorylation of IκBα and p38 MAPK.

TLR2 ligand pretreatment attenuated microglial inflammatory response but enhanced their phagocytic activity for S. aureus.

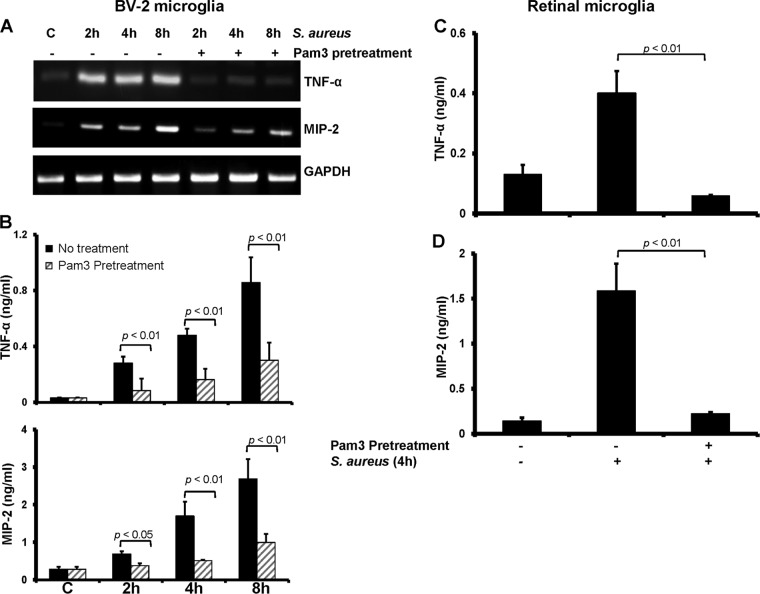

Previously, we demonstrated that intravitreal injections of TLR2 ligand Pam3Cys attenuated the inflammatory response incited by S. aureus infection (29). To determine how TLR2 ligand pretreatment modulates the microglial innate response to S. aureus, we preexposed BV-2 cells with Pam3Cys (0.1 μg/ml) for 24 h and subsequently challenged them with live S. aureus for various times. As shown in Fig. 8A, compared to no treatment, Pam3Cys pretreatment drastically reduced the mRNA expression of TNF-α and MIP-2 in response to S. aureus challenge. Similar to reduced mRNA expression, the secretion of TNF-α and MIP-2 was also significantly decreased by Pam3Cys pretreatment at all time points tested (Fig. 8B). This phenomenon was also observed in primary retinal microglia (Fig. 8C and D).

Fig 8.

Microglial inflammatory response is attenuated by TLR2 ligand pretreatment. BV-2 microglia were pretreated for 24 h with 1 μg/ml of Pam3Cys and then challenged for 2, 4, or 8 h with live S. aureus. Cells were harvested for RNA extraction and RT-PCR analysis of TNF-α and MIP-2 genes (A), whereas culture supernatants were used for quantitation of protein levels by ELISA (B). Similarly, primary retinal microglia were pretreated with a low dose of Pam3 (0.1 μg/ml) for 24 h followed by stimulation with live S. aureus for 4 h. At the end of the incubation period, culture supernatants were collected and levels of TNF-α (C) and MIP-2 (D) were measured by ELISA. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test.

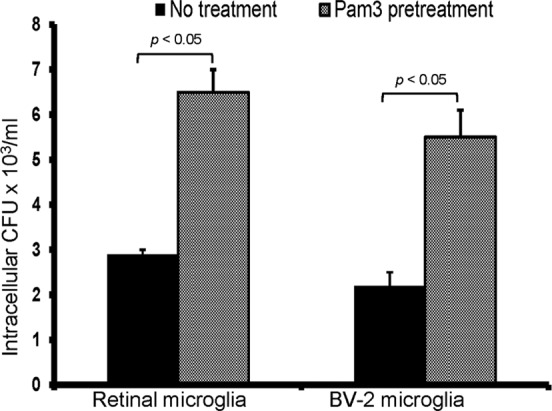

In addition to producing inflammatory mediators to alert the immune system, the other key function of microglia is to phagocytose the invading pathogens and dying cells. The results presented above indicate that the microglial inflammatory response is attenuated by TLR2 ligand pretreatment; therefore, we next tested its effect on microglial phagocytic activity. Prestimulation of both BV-2 and primary microglia with Pam3Cys significantly enhanced their phagocytic activity, as evidenced by the increased number of intracellular bacteria in pretreated versus untreated cells (Fig. 9).

Fig 9.

TLR2 activation increases the phagocytic activity of retinal microglia for S. aureus. To assess the effect of TLR2 activation, BV-2 and primary retinal microglia were either left untreated or pretreated with Pam3Cys (0.1 μg/ml) for 24 h followed by a 1-h challenge with S. aureus as described in Materials and Methods. After stimulation, cells were washed and kept in fresh medium containing gentamicin (200 μg/ml) for 2 h followed by cell lysis. The release of intracellular bacteria was quantitated by plate count. Statistical analysis was performed by using the Student t test.

S. aureus invasion in endophthalmitis.

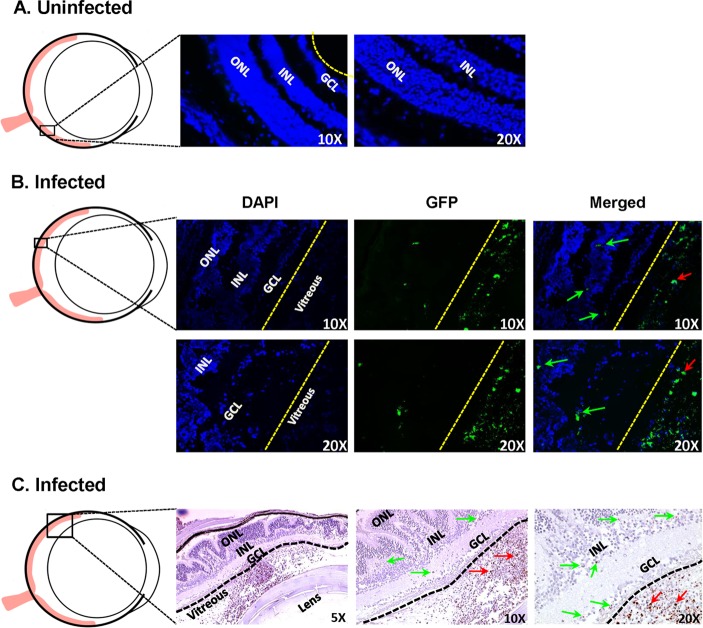

Our data showed an increased infiltration of CD45+ CD11b+ microglia/macrophages in infected eyes (Fig. 1); therefore, the residential microglia may need direct interaction to phagocytose the invading pathogens. To test whether S. aureus can invade the retina, we used GFP-expressing S. aureus and examined the eyes at different time points. In control (uninfected) eyes, no GFP fluorescence was detected in the retina (Fig. 10A). In contrast, GFP fluorescence was detected in retinal GCL and INL, and significantly higher GFP fluorescence was observed in the vitreous of infected eyes, indicating inoculated and/or proliferating bacteria (Fig. 10B). This increased fluorescence was more noticeable 24 h postinjection. Infected eyes examined at 24 h and later showed increased disorganization of retinal structures due to massive infiltration. Consequently, the presence of staphylococci in the retina was ascertained by using GFP tagging in paraffin-fixed sections. Similar to direct GFP fluorescence in cryosections, GFP immunoreactivity was detected in retinal layers and vitreous of infected eyes (Fig. 10C).

Fig 10.

Presence of S. aureus in retinal tissue. Mice were given intravitreal injections of PBS (uninfected) (A) or 5,000 CFU of GFP-expressing S. aureus (B and C). After 36 h, enucleated eyes were either embedded in OCT or fixed in paraffin. Cryosections were subjected to direct GFP fluorescence imaging (A and B), whereas paraffin-embedded sections were incubated with rabbit anti-GFP antibody followed by detection with rabbit ImmPress and AEC peroxidase substrate (Vector labs), and hematoxylin was used for counterstaining (C). Green and red arrows show GFP positivity in retinal layers and the vitreous cavities, respectively, of infected eyes (n = 3). GCL, ganglion cell layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer.

DISCUSSION

The innate immune system of the retina, like that of the brain, consists of microglia, astrocytes, and the perivascular macrophages, which line the blood vessels (60). Thus, these cells potentially mediate the initial innate response, which combats invading pathogens, and eventually recruit peripheral neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes to the retina. In contrast to numerous studies of microglia in brain tissue (1, 26), few reports are available on retinal microglial activation, particularly in bacterial endophthalmitis. In this study, using a C57BL/6 mouse model of bacterial endophthalmitis, we demonstrated that S. aureus induces the activation of retinal microglia. Additionally, we investigated the role of TLR2 (a key receptor implicated in recognizing Gram-positive bacteria) in retinal microglial activation. We showed that these cells express TLR2 and that its expression is increased by bacterial challenge. Furthermore, S. aureus and its cell wall components (PGN and LTA) mediated the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, and this response is inhibited by pretreatment of retinal microglia with TLR2-neutralizing antibody or siRNA transfection. Finally, we tested how microglial innate response is modulated by TLR2 ligand pretreatment and showed that while pretreatment dampened the inflammatory response to S. aureus challenge, it dramatically enhanced microglial phagocytic activity. Thus, we propose that modulation of TLR signaling may be utilized as a novel approach for anti-inflammatory therapy.

Microglia perform several key functions, including monitoring the tissue environment for pathogens, maintaining tissue homeostasis, phagocytosing dead cells, and responding rapidly to perturbations in the local environment (12). Normally, retinal microglia reside in the inner and outer plexiform layers of the retina, but under pathogenic conditions, they undergo a variety of structural changes based on their location and roles (22).This level of plasticity allows them to respond to tissue injury and stress in an extremely short time without causing an immunological imbalance (17). We hypothesized that in infectious endophthalmitis, retinal microglia will be the first responders to invading pathogens. Our data demonstrated that S. aureus infection significantly increased the number of retinal microglia and also altered their distribution. Furthermore, using cultured microglia of retinal origin, we showed that these cells recognize and respond to S. aureus by secreting various inflammatory mediators, which in turn may recruit immune cells to the retina. Hence, our findings suggest that microglia play an important role in initiating early innate responses to bacterial endophthalmitis.

The mechanisms that trigger retinal microglial activation in bacterial endophthalmitis are generally unknown. However, based on bacterial meningitis (18, 36) and brain abscess (24) studies, it can be postulated that Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are likely to be involved. Several studies recently demonstrated TLR2 expression on brain microglia (14, 57, 62); however, the functional significance of this receptor in the context of retinal microglial recognition of Gram-positive bacteria remained to be directly demonstrated. Thus, in this study we examined the expression of TLRs in retinal microglia and demonstrated that these cells express TLRs (TLR2 and -4) both in vivo and in vitro. In addition, exposure of retinal microglia to Pam3Cys or S. aureus led to a significant induction of TLR2 expression. Interestingly, increased expression of TLR4 mRNA was also detected in S. aureus-challenged microglia, suggesting potential interplay between TLR2 and -4, which needs further investigation. The augmented TLR levels following microglial exposure to ligands could facilitate their efficient pathogen recognition ability and rapid initiation of the innate immune response.

TLR2 is capable of recognizing a wide array of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), including peptidoglycan (PGN), bacterial lipoproteins, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and yeast zymosan (20, 61). To investigate which cell wall components of S. aureus are responsible for the activation of the retinal microglia, we exposed the cells to purified staphylococcal PGN and LTA. Our data showed that these cell wall components induced a strong inflammatory response in retinal microglia. Furthermore, we evaluated the importance of TLR2 signaling in mediating the innate microglial response to S. aureus and its cell wall components by blocking TLR2. The results demonstrate that TLR2 is essential for PGN and LTA recognition in primary retinal microglia, whereas other receptors might also be involved in signaling proinflammatory mediator production in response to live S. aureus (Fig. 5). One candidate group of receptors could be nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs), and specifically NOD2, which has been shown to regulate the innate immune response against bacterial pathogens in a TLR-independent manner (4). Moreover, studies have reported the expression of NOD2 in ocular tissues (47) and its role in uveitis (48, 49). The canonical TLR signaling cascade after pathogen recognition leads to the activation of NF-κB and the subsequent production of proinflammatory mediators (23). In this study, we showed that S. aureus challenge of microglia stimulates the NF-κB and MAPK signal transduction cascade via elevated levels of phosphorylated IκB and p38 MAPK, indicative of their involvement in inflammatory responses.

The early innate response incited by infection plays an important role in bacterial clearance (19); however, its dysregulation can lead to bystander damage to neurons, a phenomenon referred to as inflammatory neurodegeneration (2). Indeed, an excessive immune response is thought to be largely responsible for neuronal death in both Gram-positive bacterial meningitis and brain abscesses (15, 37). Therefore, an optimal treatment approach for inflammation-sensitive tissue, such as the retina, may include recruiting enough activated inflammatory cells to allow complete bacterial clearance while minimizing secondary host-mediated damage. One way to achieve this is through immunomodulation therapies that permit fine-tuning of the intraocular inflammatory response. Working on this idea, we recently demonstrated that intravitreal injection of TLR2 ligand prior to bacterial inoculation prevented the development of staphylococcal endophthalmitis. This protective effect was attributed to reduced inflammatory response and enhanced bacterial clearance (29). In the previous study, microglia were implicated as playing an important role in TLR2-mediated protective effects, but in the present study, using in vitro approaches, we specifically investigated the modulation of retinal microglial innate responses by TLR2 ligand pretreatment. An important mechanism regulating TLR signaling pathways is the development of tolerance, characterized by a transient period of hyporesponsiveness leading to impaired inflammatory response on subsequent TLR ligand challenge (40). This negative feedback mechanism is important for protecting the host against tissue damage and lethality caused by excessive inflammation (8). In relation to this, we explored ways to modulate the TLR2-mediated inflammatory response, and we found that pretreating microglia with a low dose of Pam3Cys attenuated the expression and production of proinflammatory cytokines. Thus, the muting of TLR2-mediated signaling pathways appears sufficient to attenuate the inflammatory response of microglia to Gram-positive bacteria such as S. aureus, and targeting TLR2 with Pam3Cys may be a useful pharmacologic approach to the modulation of inflammation associated with endophthalmitis.

In addition to producing inflammatory mediators, another key characteristic of microglia is their ability to phagocytose the invading pathogen (21). Reactive microglia develop a phagocytic phenotype, engulfing and killing microbes and presenting antigens to recruit other cells to the site of infection, thereby initiating an adaptive immune response (57). Since TLR2 ligand pretreatment influenced retinal microglial inflammatory response, we reasoned that pretreatment would stimulate microglia and might increase their phagocytic activity toward bacteria. Our data showed that pretreatment of both retinal and BV-2 microglial cells through TLR2 increases their ability to phagocytose S. aureus. This is consistent with recent studies in which brain microglia were found to have increased phagocytic activity following TLR2 (46), TLR3 (46), TLR4, and TLR9 ligand prestimulation (45). These studies highlighted the importance of phagocytic activity of microglia in protecting the brain from invasive (e.g., pneumococcal) bacterial infections, especially in patients with an impaired immune system. In our endophthalmitis model, the bacterium is injected in the vitreous cavity. To ascertain whether S. aureus can invade the retina, we used GFP-expressing bacteria and GFP-specific immunostaining. To this end, our data showed the presence of staphylococci within retinal layers. However, it should be noted that similar to previous studies (5, 33), our study showed that the majority of the staphylococci remained in the vitreous cavity. Although we were able to demonstrate the presence of bacteria in the inner retina, we observed that their number increased substantially after 24 to 48 h postinfection in parallel to the disorganization of retinal structures and massive recruitment of inflammatory cells. Based on our recent preliminary data (not published), we hypothesized that the internal limiting membrane (ILM) may play a role in providing a mechanical barrier to S. aureus invasion in the retina. In addition to postoperative causing endophthalmitis, Gram-positive bacteria, including S. aureus (44), have the potential to spread via the hematogenous route. This could lead to the development of endogenous endophthalmitis, where direct contact of the pathogen with retinal cells is very likely. Thus, enhanced phagocytic activity of retinal microglia via TLR activation may also exert protective effects in immunocompromised individuals, who are highly susceptible to developing endogenous endophthalmitis (10).

In summary, we have shown that retinal microglia express TLR2, and by preconditioning with TLR2 ligand Pam3Cys, their inflammatory response is muted, whereas their phagocytic activity is increased significantly. This implicates TLR2 as an important mediator in the modulation of retinal microglial innate response to S. aureus. Understanding this and other mechanisms of protection induced via preconditioning will further our ability to initiate and complement these pathways to minimize the retinal damage associated with endophthalmitis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant RO1 EY19888 (to A.K.), by the Alliance for Vision Research (to A.K.), and by an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness (to the Department of Ophthalmology). A.K. is also the recipient of the William & Mary Greve special scholar award from RPB.

We thank Ambrose Cheung (Dartmouth Medical School, Hanover, NH) for providing bacterial strains. We are also thankful to Loubna Hatem and Mallika Gupta for their technical support in immunostaining and tissue sectioning.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 19 March 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Bajramovic JJ. 2011. Regulation of innate immune responses in the central nervous system. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 10:4–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bal-Price A, Brown GC. 2001. Inflammatory neurodegeneration mediated by nitric oxide from activated glia-inhibiting neuronal respiration, causing glutamate release and excitotoxicity. J. Neurosci. 21:6480–6491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Broad A, Kirby JA, Jones DE. 2007. Toll-like receptor interactions: tolerance of MyD88-dependent cytokines but enhancement of MyD88-independent interferon-beta production. Immunology 120:103–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brodsky IE, Monack D. 2009. NLR-mediated control of inflammasome assembly in the host response against bacterial pathogens. Semin. Immunol. 21:199–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Callegan MC, Booth MC, Jett BD, Gilmore MS. 1999. Pathogenesis of gram-positive bacterial endophthalmitis. Infect. Immun. 67:3348–3356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Callegan MC, et al. 2007. Bacterial endophthalmitis: Therapeutic challenges and host-pathogen interactions. Prog. Ret. Eye Res. 26:189–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cario E, Gerken G, Podolsky DK. 2007. Toll-like receptor 2 controls mucosal inflammation by regulating epithelial barrier function. Gastroenterology 132:1359–1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cavaillon JM, Adrie C, Fitting C, Adib-Conquy M. 2003. Endotoxin tolerance: is there a clinical relevance? J. Endotoxin Res. 9:101–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chinnery HR, et al. Accumulation of murine subretinal macrophages: effects of age, pigmentation and CX(3)CR1. Neurobiol. Aging, in press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Connell PP, et al. 2010. Endogenous endophthalmitis: 10-year experience at a tertiary referral centre. Eye (Lond.) 25:66–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Conroy H, Marshall NA, Mills KH. 2008. TLR ligand suppression or enhancement of Treg cells? A double-edged sword in immunity to tumours. Oncogene 27:168–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. David S, Kroner A. 2011. Repertoire of microglial and macrophage responses after spinal cord injury. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12:388–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dominguez-Punaro MDL, et al. 2010. In vitro characterization of the microglial inflammatory response to Streptococcus suis, an important emerging zoonotic agent of meningitis. Infect. Immun. 78:5074–5085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Esen N, Tanga FY, DeLeo JA, Kielian T. 2004. Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) mediates astrocyte activation in response to the Gram-positive bacterium Staphylococcus aureus. J. Neurochem 88:746–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Esen N, Wagoner G, Philips N. 2010. Evaluation of capsular and acapsular strains of S. aureus in an experimental brain abscess model. J. Neuroimmunol. 218:83–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feterowski C, et al. 2005. Attenuated pathogenesis of polymicrobial peritonitis in mice after TLR2 agonist pre-treatment involves ST2 up-regulation. Int. Immunol. 17:1035–1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gehrmann J, Matsumoto Y, Kreutzberg GW. 1995. Microglia: intrinsic immuneffector cell of the brain. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 20:269–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gerber J, Nau R. 2010. Mechanisms of injury in bacterial meningitis. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 23:312–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Giese MJ, et al. 2003. Mitigation of neutrophil infiltration in a rat model of early Staphylococcus aureus endophthalmitis. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 44:3077–3082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guan R, Mariuzza RA. 2007. Peptidoglycan recognition proteins of the innate immune system. Trends Microbiol. 15:127–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hanisch UK, Kettenmann H. 2007. Microglia: active sensor and versatile effector cells in the normal and pathologic brain. Nat. Neurosci. 10:1387–1394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Karlstetter M, Ebert S, Langmann T. 2010. Microglia in the healthy and degenerating retina: insights from novel mouse models. Immunobiology 215:685–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kawai T, Akira S. 2007. Signaling to NF-κB by Toll-like receptors. Trends Mol. Med. 13:460–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kielian T, Esen N, Bearden ED. 2005. Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) is pivotal for recognition of S. aureus peptidoglycan but not intact bacteria by microglia. Glia 49:567–576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Konat GW, Kielian T, Marriott I. 2006. The role of Toll-like receptors in CNS response to microbial challenge. J. Neurochem. 99:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kreutzberg GW. 1996. Microglia: a sensor for pathological events in the CNS. Trends Neurosci. 19:312–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kumar A, Gao N, Standiford TJ, Gallo RL, Yu FS. 2010. Topical flagellin protects the injured corneas from Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Microbes Infect. 12:978–989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kumar A, Hazlett LD, Yu FS. 2008. Flagellin suppresses the inflammatory response and enhances bacterial clearance in a murine model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. Infect. Immun. 76:89–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kumar A, Singh CN, Glybina IV, Mahmoud TH, Yu FS. 2010. Toll-like receptor 2 ligand-induced protection against bacterial endophthalmitis. J. Infect. Dis. 201:255–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kumar A, Yin J, Zhang J, Yu FS. 2007. Modulation of corneal epithelial innate immune response to pseudomonas infection by flagellin pretreatment. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 48:4664–4670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kumar A, Zhang J, Yu FS. 2004. Innate immune response of corneal epithelial cells to Staphylococcus aureus infection: role of peptidoglycan in stimulating proinflammatory cytokine secretion. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 45:3513–3522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lehner MD, et al. 2001. Improved innate immunity of endotoxin-tolerant mice increases resistance to Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection despite attenuated cytokine response. Infect. Immun. 69:463–471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Leid JG, Costerton JW, Shirtliff ME, Gilmore MS, Engelbert M. 2002. Immunology of Staphylococcal biofilm infections in the eye: new tools to study biofilm endophthalmitis. DNA Cell Biol. 21:405–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li CH, Wang JH, Redmond HP. 2006. Bacterial lipoprotein-induced self-tolerance and cross-tolerance to LPS are associated with reduced IRAK-1 expression and MyD88-IRAK complex formation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 79:867–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lin HY, et al. 2011. Peptidoglycan induces interleukin-6 expression through the TLR2 receptor, JNK, c-Jun, and AP-1 pathways in microglia. J. Cell. Physiol. 226:1573–1582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu S, Kielian T. 2009. Microglial activation by Citrobacter koseri is mediated by TLR4- and MyD88-dependent pathways. J. Immunol. 183:5537–5547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu X, Chauhan VS, Young AB, Marriott I. 2010. NOD2 mediates inflammatory responses of primary murine glia to Streptococcus pneumoniae. Glia 58:839–847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mariani MM, Kielian T. 2009. Microglia in infectious diseases of the central nervous system. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 4:448–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Medvedev AE, Kopydlowski KM, Vogel SN. 2000. Inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced signal transduction in endotoxin-tolerized mouse macrophages: dysregulation of cytokine, chemokine, and toll-like receptor 2 and 4 gene expression. J. Immunol. 164:5564–5574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Medvedev AE, Sabroe I, Hasday JD, Vogel SN. 2006. Tolerance to microbial TLR ligands: molecular mechanisms and relevance to disease. J. Endotoxin Res. 12:133–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Miyake K. 2007. Innate immune sensing of pathogens and danger signals by cell surface Toll-like receptors. Semin. Immunol. 19:3–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Moyer AL, Ramadan RT, Novosad BD, Astley R, Callegan MC. 2009. Bacillus cereus-induced permeability of the blood-ocular barrier during experimental endophthalmitis. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50:3783–3793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mullaly SC, Kubes P. 2006. The role of TLR2 in vivo following challenge with Staphylococcus aureus and prototypic ligands. J. Immunol. 177:8154–8163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ness T, Schneider C. 2009. Endogenous endophthalmitis caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Retina 29:831–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ribes S, et al. 2009. Toll-like receptor prestimulation increases phagocytosis of Escherichia coli DH5α and Escherichia coli K1 strains by murine microglial cells. Infect. Immun. 77:557–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ribes S, et al. 2010. Toll-like receptor stimulation enhances phagocytosis and intracellular killing of nonencapsulated and encapsulated Streptococcus pneumoniae by murine microglia. Infect. Immun. 78:865–871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rodriguez-Martinez S, Cancino-Diaz ME, Jimenez-Zamudio L, Garcia-Latorre E, Cancino-Diaz JC. 2005. TLRs and NODs mRNA expression pattern in healthy mouse eye. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 89:904–910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rosenzweig HL, et al. 2009. Nucleotide oligomerization domain-2 (NOD2)-induced uveitis: dependence on IFN-gamma. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 50:1739–1745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rosenzweig HL, et al. 2008. NOD2, the gene responsible for familial granulomatous uveitis, in a mouse model of uveitis. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 49:1518–1524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ruggiero G, Andreana A, Utili R, Galante D. 1980. Enhanced phagocytosis and bactericidal activity of hepatic reticuloendothelial system during endotoxin tolerance. Infect. Immun. 27:798–803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shi XQ, Zekki H, Zhang J. 2011. The role of TLR2 in nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain is essentially mediated through macrophages in peripheral inflammatory response. Glia 59:231–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Skeie JM, Tsang SH, Mahajan VB. 2011. Evisceration of mouse vitreous and retina for proteomic analyses. J. Vis. Exp. 2011:2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Stewart CR, et al. 2010. CD36 ligands promote sterile inflammation through assembly of a Toll-like receptor 4 and 6 heterodimer. Nat. Immunol. 11:155–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Takeuchi O, Hoshino K, Akira S. 2000. Cutting edge: TLR2-deficient and MyD88-deficient mice are highly susceptible to Staphylococcus aureus infection. J. Immunol. 165:5392–5396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Takeuchi O, et al. 1999. Differential roles of TLR2 and TLR4 in recognition of gram-negative and gram-positive bacterial cell wall components. Immunity 11:443–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Varma TK, et al. 2005. Endotoxin priming improves clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in wild-type and interleukin-10 knockout mice. Infect. Immun. 73:7340–7347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vidlak D, Mariani MM, Aldrich A, Liu S, Kielian T. 2011. Roles of Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and superantigens on adaptive immune responses during CNS staphylococcal infection. Brain Behav. Immun. 25:905–914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Vijay-Kumar M, et al. 2006. Flagellin suppresses epithelial apoptosis and limits disease during enteric infection. Am. J. Pathol. 169:1686–1700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Willis LM, Bielinski DF, Fisher DR, Matthan NR, Joseph JA. 2010. Walnut extract inhibits LPS-induced activation of BV-2 microglia via internalization of TLR4: possible involvement of phospholipase D2. Inflammation 33:325–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Xu H, Chen M, Forrester JV. 2009. Para-inflammation in the aging retina. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 28:348–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zahringer U, Lindner B, Inamura S, Heine H, Alexander C. 2008. TLR2 - promiscuous or specific? A critical re-evaluation of a receptor expressing apparent broad specificity. Immunobiology 213:205–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zhang Y, et al. 2011. Essential role of Toll-like receptor 2 in morphine-induced microglia activation in mice. Neurosci. Lett. 489:43–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]