Summary

P-values are useful statistical measures of evidence against a null hypothesis. In contrast to other statistical estimates, however, their sample-to-sample variability is usually not considered or estimated, and therefore not fully appreciated. Via a systematic study of log-scale p-value standard errors, bootstrap prediction bounds, and reproducibility probabilities for future replicate p-values, we show that p-values exhibit surprisingly large variability in typical data situations. In addition to providing context to discussions about the failure of statistical results to replicate, our findings shed light on the relative value of exact p-values vis-a-vis approximate p-values, and indicate that the use of *, **, and *** to denote levels .05, .01, and .001 of statistical significance in subject-matter journals is about the right level of precision for reporting p-values when judged by widely accepted rules for rounding statistical estimates.

Key words and phrases: log p-value, measure of evidence, prediction interval, reproducibility probability

1 Introduction

Good statistical practice demands reporting some measure of variability or reliability for important statistical estimates. For example, if a population mean μ is estimated by a sample mean Y̅ using an independent and identically distributed (iid) sample Y1, …, Yn, common practice is to report a standard error or a confidence interval for μ, or their Bayesian equivalents. However, the variability of a p-value is typically not assessed or reported in routine data analysis, even when it is the primary statistical estimate.

More generally, statisticians are quick to emphasize that statistics have sampling distributions and that it is important to interpret those statistics in view of their sampling variation. However, the caveat about interpretation is often overlooked when the statistic is a p-value. With any statistic, ignoring variability can have undesirable consequences. In the case of the p-value, the main problem is that too much stock may be placed in a finding that is deemed statistically significant by a p-value < .05. In this paper we systematically study p-value variability with an eye toward developing a better appreciation of its magnitude and potential impacts, especially those related to the profusion of scientific results that fail to reproduce upon replication.

Under alternative hypotheses, p-values are less variable than they are under null hypotheses, where for continuous cases the Uniform(0,1) standard deviation 12−1/2 = 0.29 applies. However, under alternatives their standard deviations are typically large fractions of their mean values, and thus p-values are inherently imprecise. Papers such as Goodman (1992) and Gelman and Stern (2006) address this variability, yet the subject deserves more attention because p-values play such an important role in practice. Ignoring variability in p-values is potentially misleading just as ignoring the standard error of a mean can be misleading.

The science of Statistics has recently come under attack for its purported role in the failure of statistical findings to hold up under the litmus test of replication. In Odds Are, It’s Wrong: Science fails to face the shortcomings of statistics, Siegfried (2010) highlights Science’s love affair with p-values and argues that their shortcomings, and the shortcomings of Statistics more generally, are responsible for the profusion of faulty scientific claims. Pantula et al. (2010) responded on behalf of the American Statistical Association and the International Statistical Institute, pointing out that Siegfried’s failure to distinguish between the limitations of statistical science and the misuse of statistical methods results in erroneous conclusions about the role of statistics in the profusion of false scientific claims. Lack of replication in studies and related statistical issues have been highlighted recently in interesting presentations by Young (2008), who points to multiple testing, multiple methodologies (trying many different methods of analysis), and bias as particular problems. In fact, results fail to replicate for a number of reasons. In order to correctly assess their impacts, it is necessary to understand the role of p-value variability itself.

We study three approaches to quantifying p-value variability. First, we consider the statistician’s general purpose measure of variability, the standard deviation and its estimate, the standard error. We show that −log10(p-value) standard deviations are such that for a wide range of observed significance levels, only the magnitude of −log10(p-value) is reliably determined. That is, writing the p-value as x · 10−k, where 1 ≤ x < 10 and k = 1, 2, 3, … is the magnitude so that −log10(p-value) = −log10(x) + k, the standard deviation of −log10(p-value) is so large relative to its value that only the magnitude k is reliably determined as a measure of evidence. This phenomenon is manifest in standard errors derived from both the bootstrap and from asymptotic approximations based on the results of Lambert and Hall (1982). Second, using results from Mojirsheibani and Tibshirani (1996), we argue that bootstrap prediction intervals and bounds for the p-value from an independent replication of the original experiment, herein denoted by pnew, are soberingly wide. Third and finally, estimates of P(pnew ≤ .05), introduced by Goodman (1992), and called reproducibility probabilities by Shao and Chow (2002) and De Martini (2008), are studied revealing that significance, as judged by p-value ≤ .05, is often likely not to replicate. As explained more fully later in this section, bootstrap sampling used in this article is not resampling under a null hypothesis, but rather resampling that preserves the true sampling characteristics, whether they be null or nonnull. 1

We open with a simple example illustrating each of these three approaches to assessing p-value uncertainty. Then we study each approach in greater detail in following sections.

Miller (1986, p. 65) gives data from a study comparing partial thromboplastin times for patients whose blood clots were dissolved (R=recanalized) and for those whose clots were not dissolved (NR):

R: 41, 86, 90, 74, 146, 57, 62, 78, 55, 105, 46, 94, 26, 101, 72, 119, 88

NR: 34, 23, 36, 25, 35, 23, 87, 48

Relevant summary descriptive statistics are Y̅1 = 78.82352941176471, s1 = 30.09409263899987, Y̅2 = 38.87500000000000, s2 = 21.18919873088982. If you think that reporting these statistics to fourteen decimal places is excessive, then you tacitly agree with a basic premise of this paper—it is silly to retain all these decimals because analysis of these statistics’ standard errors reveals their imprecision. For example, standard errors of the two means are , respectively, with corresponding normal-approximation 95% confidence intervals (64, 93) and (24, 54). From these sample means, not even the first digits of the population means are well determined. However, since the data are integer-valued, most people would be comfortable reporting Y̅1 = 79 and Y̅2 = 39. See Ehrenberg (1977) and Wainer (1997) for basic numeracy guidelines. Certainly extra digits are useful for further calculations, but they are misleading when making decisions.

Our interest is in testing the difference of means, and the relevant summary statistics are Y̅D = 40, with pooled-variance standard error s = 10, and normal-approximation 95% confidence interval (19, 61). Despite the large variability in the estimated difference of means, there is evidence that the means differ, and this is reflected in both the exact two-sided Wilcoxon Rank Sum test p-value=0.001443266, and the normal-approximation (without continuity correction) p-value=0.002446738. Although one p-value is exact and the other is approximate, both are reported with unwarranted precision. Nonparametric bootstrap standard errors for these two p-values are both approximately 0.04, suggesting that the observed difference between the two p-values is small relative to the variability in either one.2 However, because the distribution of the p-value is highly skewed, it is preferable to work on the log scale.

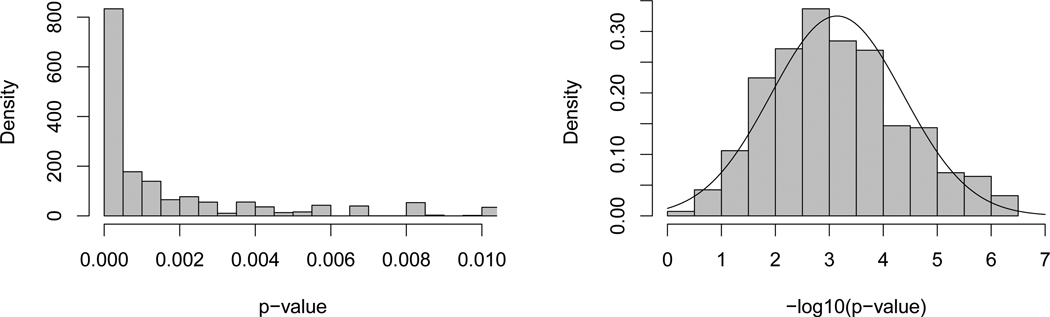

Converting to base 10 logarithms (natural logarithms are denoted by log rather than ln), we have −log10(0.0014) = 2.9 for the exact p-value with bootstrap standard error 1.2, and −log10(0.0024) = 2.6 for the normal approximation p-value with bootstrap standard error 0.8. These standard errors suggest rounding both −log10 values to 3 and back transforming to 0.001 on the p-value scale. Figure 1 illustrates the −log10 transformation to normality with histograms of the bootstrap sample p-values and their −log10 transformation.

Figure 1.

Histograms of nonparametric bootstrap p-values for Wilcoxon Rank Sum example (left panel) and −log10 transformed p-values with approximating normal density overlaid (right panel).

These two p-values allow us to illustrate our previous claim that often only the magnitude of a p-value is well determined. The exact p-value is 0.0014 = x × 10−k where −log10(x) = −0.15 and k = 3. Thus only k is “large” relative to the bootstrap standard error 1.2. For the normal approximation p-value, the corresponding breakdown is 0.0024 = x × 10−k where −log10(x) = −0.38 and k = 3, with bootstrap standard error 0.8.

The nonparametric bootstrap was used to calculate the standard errors reported above and the values used to compose Figure 1. Keep in mind that in these applications of the bootstrap, the target estimate is a p-value, i.e., a p-value is computed for each bootstrap sample. We are using the bootstrap to assess the sampling variability of the p-value, not the sampling variability of the p-value under a null-hypothesis assumption as is more commonly done. Thus the bootstrap sampling used here preserves the non-null property of the data. Specifically for this example, a single bootstrap p-value was obtained by randomly selecting 17 values with replacement from the 17 values in the R sample, then independently drawing 8 values with replacement from the 8 values in the NR sample. Next the exact Wilcoxon Rank Sum test p-value was calculated using the R package exactRankTests and function wilcox.exact (Hothorn and Hornik, 2006). This process was repeated to obtain a total of B = 9999 bootstrap p-values that were used in Figure 1. The bootstrap standard errors for the p-value and log10(p-value) were obtained by calculating the sample standard deviation of the respective B = 9999 bootstrap values.

The analysis of p-value and log10(p-value) standard errors for the Miller data illustrates the generally observed phenomenon that the large variability of the p-values implies that only the magnitude of the p-value is accurate enough to be reliably reported. This observation runs counter to the current emphasis on reporting exact p-values, but it roughly coincides with use of *, **, and *** to denote levels of statistical significance often found in subject-matter journals.

Complementing the assessment of variability for the Miller data based on the analysis of p-value and log10(p-value) standard errors are the two inferential techniques defined in terms of pnew. Recall that pnew is a new p-value obtained from a hypothetical independent replication of the experiment.

A nonparametric upper prediction bound for pnew. Just as prediction bounds for a new response variable provide an indication of the range of likely values, prediction bounds for pnew provide a range of likely values for replicate p-values. For the Miller data, using the Mojirsheibani and Tibshirani (1996) bootstrap methodology, the 90% bounds are 0.11 for both the exact and approximate p-values. The interpretation is that in repeated repetitions of the whole process, the original experiment and an independent replication, on average 90% of the pnew will be below the 90% bound. Of course, from exchangeability of the original p-value and pnew, the p-value itself is a 50% bound; i.e., we can expect 50% of the independent replication p-values to be below and 50% above the observed p-value.

An estimate of P(pnew ≤ .05). Such an estimate has been called a reproducibility probability by Shao and Chow (2002) and De Martini (2008). The idea of considering the probability of rejection in a replicate experiment was introduced by Goodman (1992). Using the bias-corrected bootstrap procedure described in Section 4, we obtain 0.84 for estimates of P(pnew ≤ .05) for both the exact and approximate p-values for the Miller data.

There are a number of articles related to the distribution of p-values under an alternative. The most relevant ones to our work are Lambert (1981) and Lambert and Hall (1982) on the asymptotic normality of −log10(p-value) and the sequence of papers on reproducibility probabilities begun by Goodman (1992). Huang et al. (1997) and Donahue (1999) discuss the distribution of p-values under alternatives, and Dempster and Schatzoff (1965), Joiner (1969), and Sackrowitz and Samuel-Cahn (1999) discuss the expected value of the p-value under alternatives. Murdoch et al. (2008) propose teaching p-values in introductory courses using simulation experiments. Their approach emphasizes that p-values are indeed random variables and thus is consonant with our theme.

One point often made is that p-values naturally combine many aspects of a problem into one number and therefore are not fully informative about experimental results. Good statistical practice is to supplement hypothesis testing results with plots of data, point estimates, and confidence or credibility intervals. Our work suggests supplementing p-values with standard errors or with one of the two measures above based on pnew.

Section 2 discusses the asymptotic normality of −log(p-value), and Section 3 gives the related variance estimation. Then Sections 4 and 5 introduce the prediction intervals and reproducibility probability estimates for the p-value of a replicated experiment. We conclude with a short discussion section.

2 Asymptotic Normality of −log(p-value)

For a variety of testing situations for a parameter θ based on a sample of n independent observations, Lambert and Hall (1982) prove that

| (1) |

or equivalently that −log(p-value) is asymptotically normal with asymptotic mean nc(θ) and asymptotic variance nτ2(θ). This asymptotic normality implies that

| (2) |

The value 2c(θ) is called the slope of the test, and a ratio of slopes for two tests is the definition of Bahadur efficiency (Bahadur, 1960). The connections of (1) with Bahadur efficiency are discussed in Lambert and Hall (1982) but are not relevant to our work.

As an illustration of (1), consider samples of size n from a normal distribution with mean μ and variance σ2 = 1 and the hypotheses H0 : μ = 0 vs. Ha : μ > 0. If one assumes that the variance is known and is used to obtain the p-value, then Lambert and Hall (1982, Table 1) give that c(μ) = μ2/2 and τ2(μ) = μ2. A similar result obtains in the unknown variance case where the usual replaces Z: c(μ) = (1/2) log(1+μ2) and τ2(μ) = μ2(1 + μ2)−2(1 + μ2/2) (using the correction in Lambert and Hall, 1983).

Table 1.

Distribution summaries for the t-test p-value and −log10(p-value) for the normal location problem, H0 : μ = 0 versus Ha : μ > 0, σ = 1 unknown.

| p-value | −log10(p-value) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Skew | Kurt | Mean | SD | Skew | Kurt | |

| n = 10, μ = 0.5 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 1.87 | 6.5 | 1.29 | 0.77 | 0.99 | 4.2 |

| n = 10, μ = 1.0 | 0.020 | 0.044 | 5.6 | 49 | 2.39 | 0.91 | 0.58 | 3.5 |

| n = 20, μ = 0.5 | 0.062 | 0.109 | 3.25 | 16.1 | 1.89 | 0.98 | 0.85 | 4.1 |

| n = 20, μ = 1.0 | 0.002 | 0.008 | 14 | 280 | 4.07 | 1.26 | 0.47 | 3.4 |

| n = 50, μ = 0.5 | 0.007 | 0.026 | 8.8 | 110 | 3.51 | 1.41 | 0.60 | 3.4 |

| n = 50, μ = 1.0 | 8e-07 | 1.1e-05 | 50 | 3600 | 8.75 | 1.93 | 0.33 | 3.1 |

Based on 10,000 Monte Carlo samples. Skew and Kurt are the moment ratios, E{X − E(X)}k/ [E{X − E(X)}2]k/2, for k = 3 and k = 4, respectively. Standard errors of entries are in the last decimal displayed or smaller.

The estimated moments in Table 1 shed light on the approximate asymptotic normality of −log10(p-value) for the one-sample t-test. Table entries were obtained via 10,000 Monte Carlo samples for each (n, μ) combination. The p-values themselves are clearly not normally distributed because the third moment ratio Skew and the fourth moment ratio Kurt, given by E{X − E(X)}k / [E{X − E(X)}2]k/2 for k = 3 and k = 4, are not close to the normal distribution values of 0 and 3, respectively. For small n the Skew values for −log10(p-value) are not close to 0, but the trend from n = 10 to n = 50 is down, and similarly the trend in the Kurt values is toward 3.

Under what conditions is the asymptotic normality of −log(p-value) to be expected? Lambert (1981, p. 65) asserts that (1) is true if the test statistic is asymptotically normal under an alternative and if some conditions exist on the tail behavior such as convergence of third moments. Examples where asymptotic normality might not be at first apparent are the goodness-of-fit statistics based on a weighted Cramer-von Mises distance between the empirical distribution function of an iid sample and an estimated true cumulative distribution function Fθ̂ (y),

| (3) |

Under H0 : true cdf = Fθ, (3) has a nonnormal asymptotic distribution, but when H0 is not true, dw(Fn, Fθ̂) is asymptotically normal. Boos (1981) gives the relevant asymptotic normal theory of dw(Fn, Fθ̂) under the alternative, but a firm proof that −log(p-value) is asymptotically normal requires additional results on the tail behavior of the null distribution of dw(Fn, Fθ̂). We use (3) with the Anderson-Darling weight function w(x) = {x(1 − x)}−1 as a check on approximate normality in several simulated examples because the combination of a nonnormal null distribution with a normal nonnull distribution adds breadth to the scope of application of the methods we study.

Another example is one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). For simplicity, consider the case of k = 3 normal samples from populations with possibly different means but the same known variance σ2 and equal sample size n. In this case, the null distribution of is exactly with distribution function 1 − exp(−x/2). Thus, −log(p-value) is T/2, certainly not normally distributed. However, it is not hard to show that for any fixed set of non-identical population means, T/2 is asymptotically normal as n → ∞.

The asymptotic normal results for −log(p-value) discussed above and various simulations like those in Table 1 suggest that the natural log or log10 is a reasonable scale on which to consider the variability of p-values. Asymptotic normality also supports the validity of the bootstrap and jackknife standard errors for −log10(p-value) proposed in the next section.

On a more practical level, the asymptotic normal results for −log10(p-value) supplemented by simulation, allow comparison of the standard deviation of −log10(p-value) to its mean value. We shall see that in typical testing situations, the standard deviation is a large fraction of the mean of −log10(p-value). This large fraction was illustrated in the introduction where p = 0.0014, −log10(0.0014) = 2.9, and the bootstrap standard error of −log10(p-value) is 1.2.

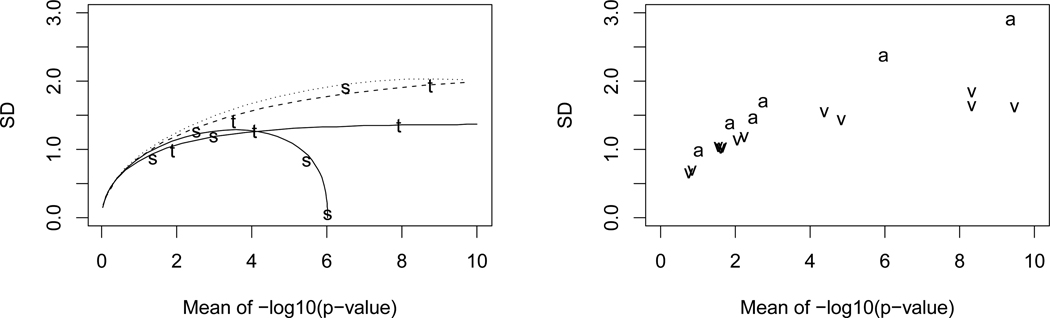

Figure 2 displays plots of Monte Carlo standard deviations versus Monte Carlo means of −log10(p-value) for the t-test (t), the sign test (s), the Anderson-Darling test for normality (a), and the one-way ANOVA F test (υ). For the t-test and sign test, the corresponding approximate theoretical curves obtained from the asymptotic normality formulas are plotted. Specifically, from (1) the asymptotic mean and standard deviation of −log(p-value) are nc(θ) and n1/2τ(θ), respectively. Multiplying by 1/log(10) = 0.4343 converts to base 10 logarithms. Using formulas for nc(θ) and n1/2τ(θ) from Table 1 of Lambert and Hall (1982), the left panel of Figure 2 plots the theoretical asymptotic standard deviation versus the asymptotic mean for the t-test and sign test for normal data over the range of μ = θ where 0.4343{nc(μ)} is in (0,10). The right panel is for the Anderson-Darling and ANOVA tests, but here no asymptotic formulas are available.

Figure 2.

Left: Solid lines are asymptotic standard deviation versus asymptotic mean nc(μ) for t-test (t) and sign test (s) at n = 20 for normal(μ, 1) data. Dashed and dotted lines are for n = 50. Labelled points (t, s) are Monte Carlo (MC) mean and standard deviation pairs of −log10(p-value). Right: MC standard deviations versus MC means of −log10(p-value) for Anderson-Darling test of normal data with exponential and extreme-value alternatives (a), n = 20, 50, 80; and one-way ANOVA (υ) with k = 3, 4, 5, sample size 10 in each group, and various sets of unequal means. MC standard errors of x and y coordinates bounded by .02 in left panel and by .06 in right panel.

The shape of the curve for the sign test at n = 20 is typical of test statistics that have discrete distributions. For the sign test, the descent to zero results from the fact that the one-sided p-value is the probability that a binomial(n, p = 1/2) random variable is greater than or equal to T = the number of sample values that are greater than μ0, the hypothesized null value. The smallest p-value possible occurs when T = n, p-value=P(binomial(n, p = 1/2) ≥ n) = 1/2n. For n = 20, we have −log10(1/220) = 6.0206, which is identical to the theoretical limit of nc(μ)/log(10) as μ → ∞ for the sign test from Table 1 of Lambert and Hall(1982). This value is where the curve for the sign test at n = 20 hits the horizontal axis in Figure 2.

More generally, any permutation test in the one-sample location problem, including all linear signed rank tests like the Wilcoxon signed rank test, will have the same smallest p-value because the p-values are based on the 2n sign changes of the original data, after subtracting μ0.

Similarly, every test statistic with a discrete distribution will have a smallest possible p-value for a given n, say pn,min, and a curve like that of the sign test in Figure 2 dipping back to 0 at −log10(pn,min). As the sample size grows, usually the discreteness is less apparent, and over the range (0,10) the associated curves of standard deviation versus mean of −log10(p-value) are more like the t-test. For example, at n = 50 the sign test curve dips back to 0 at −log10(1/250) = 15.05, but this is not apparent in Figure 2.

Although it is possible for p-values to have small standard deviations when the alternative is far from the null, in practice we are most concerned about p-values in the range 0.00001 to 0.10, i.e., (1,5) on the −log10 scale. In this range, Figure 2 illustrates that it is typical for the standard deviation of −log10(p-value) to range from 10% to 50% of its mean value or even higher.

3 Estimating the Variance of −log(p-value)

Nonparametric bootstrap and jackknife methods for estimating the variance of a statistic are fairly well established (e.g., Efron and Tibshirani, 1993, and Shao and Tu, 1996). Here we illustrate by simulation that the bootstrap and jackknife estimate the true variance of −log(p-value) well under an alternative in three examples. For iid one-sample problems, the nonparametric bootstrap draws B iid independent resamples with replacement from the original sample Y1, …, Yn, computes −log(p-value) for each resample, and then computes the sample variance of these B values. In Table 2, B = 999, but smaller values give similar results. The jackknife proceeds by leaving out one Yi at a time, computing −log(p-value), and then multiplying the sample variance of these “leave-1-out” estimators by (n − 1)2/n.

Table 2.

Relative bias and coefficient of variation (CV) of bootstrap and jackknife standard errors of −log10(p-value) for three tests. average of the resampling-based standard errors for −log10(p-value); S=Monte Carlo sample standard deviation of −log10(p-value).

| Null Alternative |

Binomial H0 : π = 1/3 πa = 1/2 |

t-Test H0 : μ = 0 μa = 1/2 |

Anderson-Darling Normal Extreme Value |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV | CV | CV | |||||||

| Bootstrap | 1.00 | 0.36 | 1.06 | 0.25 | 0.94 | 0.36 | |||

| Jackknife | 0.92 | 0.42 | 1.02 | 0.28 | 0.90 | 0.70 | |||

Monte Carlo replication size is 1000. Bootstrap replication size is B = 999. Standard errors for all entries are bounded by 0.04.

Table 2 displays estimated bias and coefficient of variation of the bootstrap and jackknife standard errors for −log10(p-value) for n = 20 in three testing situations: the binomial test of H0 : π = 1/3 versus Ha : π > 1/3 at πa = 1/2, where the Yi are Bernoulli(π); the one-sample t-test of H0 : μ = 0 versus Ha : μ > 0 at μa = 1/2, where the Yi are N(μ, 1); and the Anderson-Darling goodness-of-fit test for normality when the data are actually from the extreme value distribution with distribution function exp(−exp(−y)). All p-values are exact, where the accurate approximation to the exact Anderson-Darling p-values was taken from the R function ad.test in the package nortest (Gross, 2006).

Both bootstrap and jackknife standard errors are relatively unbiased as evidenced by the ratios near one, where is the Monte Carlo average of the resampling-based standard errors for −log10(p-value), and S is the Monte Carlo sample standard deviation of the −log10(p-value) values. The bootstrap, however, appears to have an advantage over the jackknife in terms of variability because the coefficient of variation (CV) of the standard errors is generally lower than that of the jackknife. This coefficient of variation is just the Monte Carlo sample standard deviation of the standard errors divided by the Monte Carlo average of the standard errors. Other alternative hypotheses gave similar results, with larger sample sizes showing improvements. For example, for the Anderson-Darling test with extreme value data at n = 50, the ratios are 0.98 and 0.95, respectively.

4 Bootstrap Prediction Intervals

As noted in the Introduction, metrics for analyzing the repeatability of p-values are often described in terms of a perfectly replicated independent experiment with resulting hypothetical p-value pnew. Exchangeability guarantees that P(pnew < pobs) = P(pobs < pnew) with common value 1/2 when the original experiment p-value, pobs, has a continuous distribution under both H0 and Ha. Thus, in the continuous case pobs is an upper (or lower) 50% prediction bound for pnew. We now explain how to use methods in Mojirsheibani and Tibshirani (1996) to get bootstrap prediction intervals and bounds for pnew.

Consider an iid random sample Y1, …, Yn and an independent replicate iid sample X1, …, Xm from the same population, and a statistic T computed from these samples resulting in TY,n and TX,m, respectively. If n = m, then TY,n and TX,n have identical distributions. Mojirsheibani and Tibshirani (1996) and Mojirsheibani (1998) derived bootstrap prediction intervals from the Y sample that contain TX,m with approximate probability 1 − α. Here we briefly describe their bias-corrected (BC) interval. Mojirsheibani and Tibshirani (1996) actually focused on bias-corrected accelerated (BCa) intervals, but we use the BC intervals for simplicity.

Let be a random resample taken with replacement from the set (Y1, …, Yn), i.e., a nonparametric bootstrap resample, and let be the statistic calculated from the resample. Repeating the process independently B times results in . Let K̂B(·) be the empirical distribution function of these , and let η̂B(α) be the related αth sample quantile. Then, the 1 − α bias-corrected (BC) bootstrap percentile prediction interval for TX,m is

| (4) |

where

Φ is the standard normal distribution function, zα/2 = Φ−1(1−α/2), and ẑ0 = Φ−1(K̂B(TY,n)). Our use of (4) is for T = p-value and for m = n, resulting in the simpler expressions . Similar to the BC confidence interval, the interval in (4) is derived under the assumption that there is a transformation g such that g(TY,n) − g(TX,m) + z0 has an approximately standard normal distribution. This is a reasonable assumption for T = p-value due to (1) and illustrated by Table 1. Consistency of these intervals should hold under weak consistency assumptions for the bootstrap distribution similar to those found in Theorem 4.1 of Shao and Tu (1996).

Table 3 displays results on the prediction intervals for the binomial test of H0 : π = 1/3 versus Ha : π > 1/3 at specific alternatives πa = 1/2 and πa = 2/3 and for the Anderson-Darling test for normality versus the extreme value and exponential distributions. In each situation of Table 3, 1000 Monte Carlo training samples were generated as well as a corresponding independent test sample. For the binomial case, a “sample” is actually a single Y distributed as binomial(n, πa). For each training sample, the intervals were computed and assessed as to whether they contain the p-value of the corresponding test sample. All computations were carried out in R (R Development Core Team, 2009).

Table 3.

Empirical coverages and average lengths of bootstrap prediction intervals for p-values from the binomial test of H0 : π = 1/3 versus Ha : π > 1/3 at πa = 1/2 and πa = 2/3 and for the Anderson-Darling test for normality.

| Binomial Test of H0 : π = 1/3 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| πa = 1/2 | πa = 2/3 | |||||||

| Lower 90% |

Upper 90% |

Interval 80% |

Average Length |

Lower 90% |

Upper 90% |

Interval 80% |

Average Length |

|

| n = 20 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.85 | 3.00 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.87 | 4.47 |

| n = 50 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.81 | 4.04 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.84 | 7.11 |

| Anderson-Darling Test for H0 : Normal Data | ||||||||

| Alternative = Extreme Value | Alternative = Exponential | |||||||

| n = 20 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.58 | 2.20 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.73 | 4.05 |

| n = 50 | 0.79 | 0.87 | 0.66 | 3.91 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.75 | 7.53 |

| n = 100 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.74 | 6.06 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.74 | 11.1 |

Monte Carlo replication size is 1000. Bootstrap estimates are based on binomial(n, π̂) or on B = 999 (Anderson-Darling Test). Standard errors for coverage accuracy are bounded by 0.016. Average length is on the base-10 logarithm scale; standard errors are a fraction of the last decimal given. “Lower” and “Upper” refer to estimated coverage probabilities for intervals of the form (L,1] and [0,U), respectively.

For binomial sampling, excellent coverage is obtained for n as small as 20. Because of the discreteness, the endpoints of the intervals were purposely constructed from the binomial(n, π̂ = Y/n) (equivalent to B = ∞ resamples) to contain at least probability 1 − α. This apparently translated into slightly higher than nominal coverage. The average interval lengths are on the log10 scale because interval lengths on the two sides of the p-value are not comparable.

For the Anderson-Darling goodness-of-fit test of normality versus the extreme value distribution in Table 3, the coverages are not very good for small sample sizes but are reasonable for n = 100. For the exponential alternative, the coverages are reasonable for n = 20, but the improvement is very minor for larger sample sizes up to n = 100. The convergence to normality of the Anderson-Darling statistic under an alternative is very slow and that is likely driving the slow convergence of the coverage of the prediction intervals.

5 Reproducibility Probability

In the previous section we gave prediction bounds for pnew from a perfect independent replication of the original experiment. Goodman (1992) defined the Reproducibility Probability as the estimated probability that pnew ≤ α in the context of a level-α test, i.e., a statistically significant result in the replicated experiment. To illustrate with a simple example, consider Y1, …, Yn iid is known. Then for testing H0 : μ = μ0 versus Ha : μ > μ0 using , the power function at an alternative μa is

If μa is the true value of μ in the original experiment producing Y1, …, Yn, then power(μa) is P(pnew ≤ α) for an exact replicate data set. The maximum likelihood estimate of this power is power(Y̅). Although Goodman (1992) defined the Reproducibility Probability (RP) as the estimated probability, we prefer to define RP to be the population parameter, RP = P(pnew ≤ α), and reserve to denote its estimator. (De Martini, 2008, makes a similar distinction.) Thus in the simple example, RP = power(μa), and

| (5) |

where Zobs is the observed value of Z for the original data and pobs the associated p-value. For a two-sided alternative, Ha : μ ≠ μ0, we have |Zobs| = −Φ−1(pobs/2) and

| (6) |

Goodman’s (1992) original definition of RP (our ) ignores the second of the two terms in (6), which is usually negligible. We note that (5) and (6) are working approximations for any test statistic that is approximately normal under both H0 and Ha.

In the one-sample normal mean problem, suppose now that is unknown. Then the power function at an alternative μa > μ0 is

where Ft,n−1,ncp is the distribution function of a non-central t with non-centrality parameter and n − 1 degrees of freedom. Similarly, Ft,n−1 is the distribution function of a central t. Then substituting for ncp, where . For the two-sided test, an R implementation of as a function of the p-value (pv) is

| (7) |

Shao and Chow (2002) discussed in the context of clinical trials using two-sample t-tests. We present an extension to the one-way ANOVA is the usual pooled variance estimate. In this case, the noncentrality parameter of the noncentral F is estimated by (k − 1)Fobs.

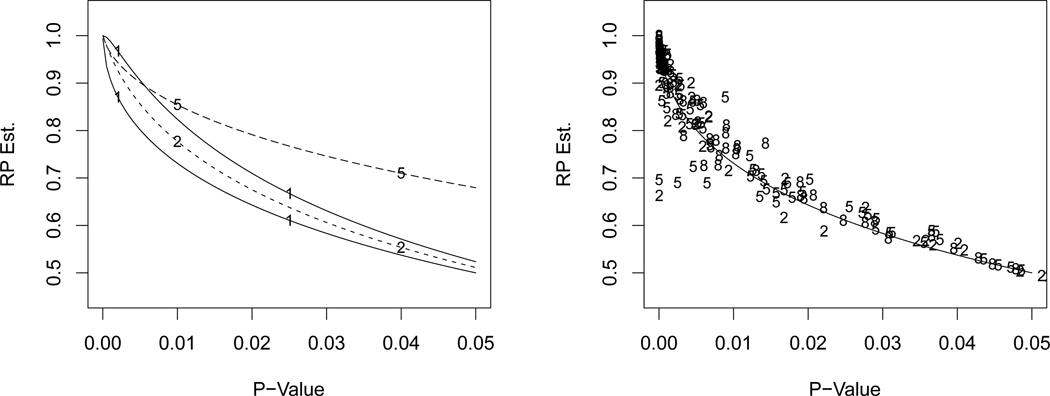

The left panel of Figure 3 plots (6) (lower solid line) and (7) with n = 10 (upper solid line). The left panel of Figure 3 also includes for the one-way ANOVA F for k = 2 and k = 5 and ni = 10 in each sample. The point to notice in this plot is that all the functions are fairly close when the p-value is near 0. As an example, the p-value that corresponds to is 0.0012 for the normal case with known variance (lower solid curve). The k = 2 samples ANOVA has p-value=0.003 corresponding to and k = 5 has p-value=0.0051. Thus, it is estimated that the probability of getting pnew ≤ .05 in an independent replication of an original experiment that has p-value near 0.001 is, approximately, 90% (see also Table 4 below).

Figure 3.

Estimated RP as a function of the two-tailed p-value for α = 0.05. Left panel: One sample normal mean with variance known (lower solid line with 1) and unknown variance with n = 10 (upper solid line with 1); dashed lines marked with 2 and 5 are for the one-way ANOVA F with k = 2 and k = 5 treatments. Right panel: Points are BC bootstrap versus p-value for the Anderson-Darling test of normality versus extreme value data (2 for n = 20, 5 for n = 50, 8 for n = 80) with the normal mean function overlaid.

Table 4.

Reproducibility probability estimates from two-sided tests of a single mean, variance known, equation (6) with α = 0.05.

| p-value | .00001 | .0001 | .001 | .005 | .01 | .02 | .03 | .04 | .05 | .10 |

| from (6) | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.91 | 0.80 | 0.73 | 0.64 | 0.58 | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0.38 |

To further affirm the approximate universality of these results, the right panel of Figure 3 plots bias-corrected bootstrap estimates of RP for the Anderson-Darling test of normality for data generated from an extreme value distribution with labels 2 for n = 20, 5 for n = 50, and 8 for n = 80, and 100 data sets for each sample size (but only results where the p-value is below 0.05 appear on the plot). These bootstrap estimates are simple bias-corrected versions of the obvious bootstrap estimate of RP given by K̂B(0.05),

| (8) |

where as before ẑ0 = Φ−1(K̂B(Tn)), and K̂B is the empirical distribution function of the B resample p-values. We have taken the lower solid curve from the left panel of Figure 3 and overlaid it on the points in the right panel. Even though the Anderson-Darling p-value is based on a non-normal null distribution, its curve is well approximated by RP curves derived under normality.

From the right panel we can also see that there is a fair amount of variability in the RP estimates from sample to sample. For example, all the “2’s” in the right panel were generated from exactly the same testing situation, and thus the sample standard deviation of all of them (ignoring the horizontal axis) approximates the true standard deviation of . In fact, for RP values less than 0.9, the standard deviations of RP estimates in a variety of situations are in the range 0.20 to 0.30. For the parametric estimates like (5) and (6), which are direct functions of the p-value, this high variability is inherited from the high variability of the p-value.

Based on the above results and further simulations not reported here, it appears possible to estimate RP from current data either using the nonparametric BC bootstrap or an estimated parametric power function like power(Y̅) in (5) and (6). However, we have found that the normal mean with variance known function in equation (6) is a reasonable approximation to these estimates in a number of different testing situations, at least when RP is large. Thus, we place some of these values in Table 4, an expanded version of a column of Table 1 of Goodman (1992).

Two other approaches to RP estimation are given in Goodman (1992) and Shao and Chow (2002). One is the Bayesian posterior predictive probability that pnew ≤ α, and the second is a 95% lower bound for RP based on a 95% lower bound for the noncentrality parameter. These are reasonable suggestions that lead to lower curves than the RP estimates given above and suggest even more caution about the reproducibility of results.

6 Discussion

Data analysts (at least most frequentists) typically accept a p-value as a useful measure of evidence against a null hypothesis. But it is likely that most are not sufficiently aware of the inherent variability in p-values except at the null hypothesis where p-values are uniformly distributed for continuous statistics. In typical examples where p-values are in the range 0.00001 to 0.10 and −log10(p-values) are thus in (1,5), the standard deviations of −log10(p-value) are between 10% and 50% of their mean value (see Figure 2). For the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test example in the Introduction, the estimated standard errors were 42% and 31% of the exact p-value and approximate p-value, respectively.

The inherent imprecision of p-values raises the question of whether exact p-values are all that more informative than approximate p-values resulting usually from large-sample approximations, and whether reporting p-values to four decimal places is illusory. It also lends support to the use of the star (*) method for reporting test results common in subject matter journals where essentially magnitudes of p-values are given rather than actual values. (The * method: * means p-value ≤ .05; ** means p-value ≤ .01; *** means p-value ≤ .001.) Finally, more emphasis on the variability of p-values would help eliminate misconceptions related to the phrase exact p-value, which carries a well-defined meaning for trained statisticians, but quite possibly connotes more than it should to subject-matter scientists who are often the producers of statistically-supported science.3

The replicate-experiment prediction intervals and RP estimates are also sobering, generally attenuating the perceived importance of any p-value in the range 0.005 to 0.05. Although either parametric or nonparametric methods can be used for RP estimation, in general (6) gives a useful rough approximation of the reproducibility of experimental statistical significance. Working backwards from (6) or scanning Table 4, we see that to have the estimate of P(pnew ≤ 0.05) at least 90%, we need pobs ≤ 0.001.

As noted in the Introduction, recent articles have lamented the lack of reproducibility in statistically-supported scientific findings, with examples in the health sciences particularly troubling. There is no doubt that multiplicity problems and multiple modeling, the high variability of p-values under the null, and publication bias all play a critical role. However, so too does the inherent variability of p-values in non-null situations. For example, suppose that in a sample of journal articles, we find p-values mostly in the range 0.005 to 0.05. Converting to the log scale, averaging, and converting back leads to a typical p-value = 0.016 and an associated noncentrality parameter for normal data that yields a power of 0.67, essentially an average of values from a grid on (0.005, 0.05). This suggests that the probability of non-replication of published studies with p-values in the range 0.005 to 0.05 is roughly 0.33. For comparison, Young (2008) reports estimates of non-reproducibility in non-randomized studies as high as 80% to 90%. Thus, the variability of p-values as presented in this article could account for an important fraction, but not all, of the observed lack of replication in studies reported in the literature.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NSF grant DMS-0906421 and NIH grant P01 CA142538-01. We thank the Editor, Associate Editor, and two referees for thoughtful comments that resulted in substantial improvements to the article’s content and its exposition.

Footnotes

Our interest is in the variability of p-values under all conditions, but especially under nonnull cases where the distribution may be far from Uniform(0, 1). Thus we simply use the bootstrap and jackknife as variance estimation methods.

Although not central to our thesis, the difference between the two p-values, −.001, has bootstrap standard error .002; and the difference between the −log10(p-values), 0.23, has bootstrap standard error 0.45. Thus as statistical estimates there is little to distinguish between the two p-values other than the modifiers “exact” and “approximate.”

That the adjective exact possibly conveys more than it should is evidenced by the persistence of Fisher’s exact test when other more powerful tests are available.

REFERENCES

- Bahadur RR. Stochastic Comparison of Tests. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1960;31:276–295. [Google Scholar]

- Boos DD. Minimum Distance Estimators for Location and Goodness-of-Fit. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1981;76:633–670. [Google Scholar]

- De Martini D. Reproducibility Probability Estimation for Testing Statistical Hypotheses. Statistics and Probability Letters. 2008;78:1056–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Dempster AP, Schatzoff M. Expected Significance Levels as a Sensitivity Index. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1965;60:420–436. [Google Scholar]

- Donahue RMJ. A Note on Information Seldom Reported Via the P Value. The American Statistician. 1999;53:303–306. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. New York: Chapman & Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenberg ASC. Rudiments Of Numeracy. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A-Statistics in Society. 1977;140:277–297. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A, Stern H. The Difference Between “Significant” and “Not Significant” is not Itself Statistically Significant. The American Statistician. 2006;60:328–331. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SN. A Comment of Replication, P-Values and Evidence. Statistics in Medicine. 1992;11:875–879. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780110705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J. Nortest: Tests for Normality. R package version 1.0. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Hung HM, O’Neill RT, Bauer P, Kohne K. The Behavior of the P-Value when the Alternative Hypothesis is True. Biometrics. 1997;53:11–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn T, Hornik K. Exact Rank Tests: Exact Distributions for Rank and Permutation Tests. R Package version 0.8–18. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Joiner BL. The Median Significance Level and Other Small Sample Measures of Test Efficacy. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1969;64:971–985. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert D. Influence Functions for Testing. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1981;76:649–657. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert D, Hall WJ. Asymptotic Lognormality of P-Values (Corr: V11 p348) The Annals of Statistics. 1982;10:44–64. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen RJ, Marx ML. An Introduction to Mathematical Statistics and Its Applications. 3rd. ed. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Miller RG. Beyond ANOVA, Basics of Applied Statistics. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Mojirsheibani M, Tibshirani R. Some Results on Bootstrap Prediction Intervals. The Canadian Journal of Statistics. 1996;24:549–568. [Google Scholar]

- Mojirsheibani M. Iterated Bootstrap Prediction Intervals. Statistica Sinica. 1998;8:489–504. [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch DJ, Tsai Y-L, Adcock J. P-Values are Random Variables. The American Statistician. 2008;62:242–245. [Google Scholar]

- Pantula SG, Teugels J, Stefanski LA. A Statistical Education. Letter to the Editor of Science News. 2010;177 Feedback #10. Published letter, http://www.sciencenews.org/view/generic/id/58594/title/Feedback Unedited letter, http://www.amstat.org/news/pdfs/OddsAreItsWrong.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sackrowitz H, Samuel-Cahn E. P Values as Random Variables—Expected P Values. The American Statistician. 1999;53:326–331. [Google Scholar]

- Shao J, Chow S-C. Reproducibility Probability in Clinical Trials. Statistics in Medicine. 2002;21:1727–1742. doi: 10.1002/sim.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao J, Tu D. The Jackknife and Bootstrap. New York: Springer; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Siegfried T. Odds Are, It’s Wrong: Science fails to face the shortcomings of statistics. Science News. 2010;177:26. http://www.sciencenews.org/view/feature/id/57091/title/Odds_Are,_Its_Wrong. [Google Scholar]

- Wainer H. Improving tabular displays, with NAEP tables as examples and inspirations. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 1997;22:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Young S. Everything is Dangerous: a Controversy. 2008 http://niss.org/sites/default/files/Young_Safety_June_2008.pdf. [Google Scholar]