Abstract

Although FDG PET is increasingly used for the staging of many types of sarcoma, little has been written regarding the FDG PET imaging characteristics of solitary fibrous tumor. We report a patient undergoing FDG PET/CT surveillance for squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue who was incidentally found to have two soft tissue masses in the retroperitoneum and pancreatic tail. Due to their low degree of FDG avidity, they were followed conservatively for approximately one year as they gradually increased in size. Technetium-99m sulfur colloid SPECT helped confirm that the pancreatic tail mass was not a splenule, after which both lesions were surgically resected and found to be extrathoracic solitary fibrous tumors without malignant features. These findings suggest that, as with other low-grade sarcomas, benign extrathoracic solitary fibrous tumors exhibit relatively little glycolytic metabolism in vivo.

Keywords: Solitary Fibrous Tumor, SFT, Sarcoma, FDG, PET/CT, Tc-99m, SPECT

CASE REPORT

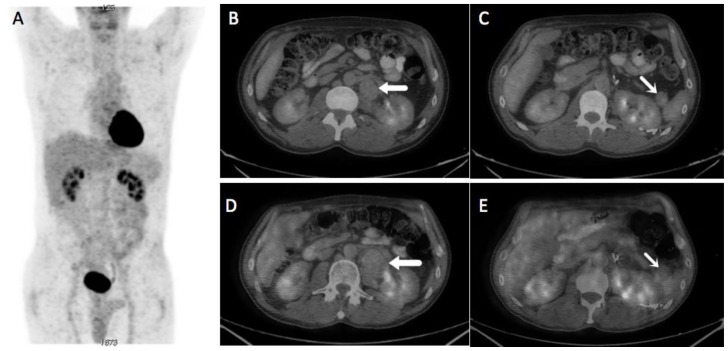

A 57-year-old male with a remote history of diaphragmatic leiomyosarcoma resected 22 years previously presented with an HPV-associated squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue, which was treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy and radiation. He underwent a PET/CT for restaging of his squamous cell carcinoma at which time two masses were found in the tail of the pancreas and retroperitoneum. (Figure 1A, B, C) These masses were followed conservatively for approximately 1 year while the patient underwent further treatment for SCC, and the pancreatic and retroperitoneal masses grew to 3.1 × 2.6 cm and 4.3 × 3.1 cm respectively. The initial SUV lean body maximum of the pancreatic and retroperitoneal masses was 1.7 and 1.5, respectively, which was similar to blood pool activity.

Figure 1.

A 57-year-old male with multifocal solitary fibrous tumors of the retroperitoneum and pancreas

A) Whole body MIP images from an FDG PET/CT performed for restaging of squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. No areas of abnormally high FDG uptake are apparent. B, C) Axial fusion images at L1-L2 from the same scan show a periaortic retroperitoneal mass (thin arrow) and a smaller mass within the pancreatic tail (thick arrow), both exhibiting only blood pool FDG uptake. D, E) Axial fusion images from a follow-up FDG PET/CT performed 11 months later demonstrate significantly size increase of the retroperitoneal mass measuring 4.3 × 3.1 cm (from 30 mL to 78 mL) as well as a more subtle size increase in the smaller pancreatic tail mass measuring 3.1 × 2.6 cm (from 12 mL to 22 mL).

(Protocol: Whole body MIP images from PET/CT, Axial fusion images from PET/CT, 120 kVp, 2.5 mm slice thickness, 120 mL Omnipaque 350, venous phase acquisition, 18 mCi F-18 FDG was injected and imaging was performed at 60 minutes. Protocol: Axial fusion images from PET/CT, CT information is as above. 12.7 mCi was injected and the patient was imaged at 55 minutes.)

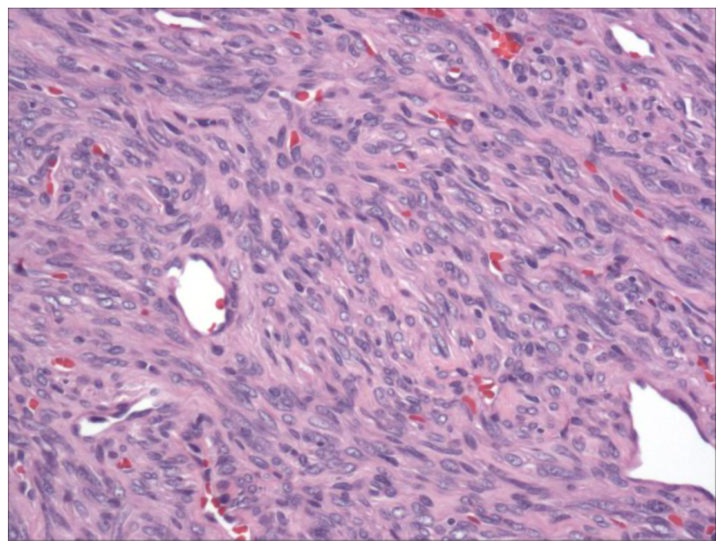

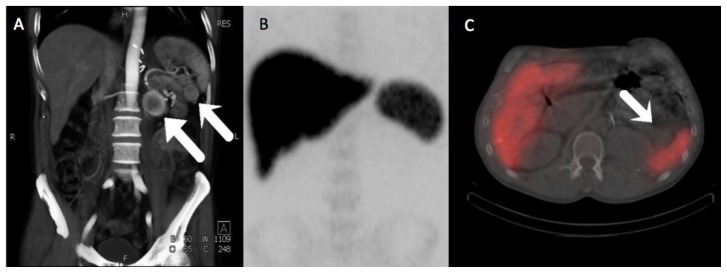

Despite its low degree of avidity, the retroperitoneal mass grew significantly during follow-up (Figure 1D), prompting a biopsy that revealed a spindle cell neoplasm (Figure 2) staining positive for CD34 and BCL-2 and negative for C-KIT, myogenin, AE1/AE3, desmin. A contrast enhanced CT scan (Figure 3A) showed avid peripheral enhancement of the retroperitoneal mass, while the pancreatic tail mass exhibited enhancement similar to that of the adjacent spleen. For purposes of surgical planning, a Tc-99m sulfur colloid SPECT was performed and confirmed that the pancreatic tail mass was not a splenule (Figure 3B, C). The patient then underwent distal pancreatectomy, splenectomy, cholecystectomy, omentectomy, and radical left nephrectomy to attain satisfactory tumor margin clearance with surgical pathology showing that both masses were solitary fibrous tumors (SFT) without malignant features. Quantitative measures of cellular proliferation suggested low-grade neoplasms, with KI-67 indices under 5% and low mitotic indices (1 per high powered field).

Figure 2.

A 57-year-old male with multifocal solitary fibrous tumors of the retroperitoneum and pancreas.

200× magnification of the solitary fibrous tumor using hematoxylin and eosin stain. The tumor displayed a classic “patternless” pattern of hyper- and hypocellular spindle cell areas, with prominent vasculature.

Figure 3.

A 57-year-old male with multifocal solitary fibrous tumors of the retroperitoneum and pancreas.

A) Three dimensional volume-rendered MIP images from a CT angiographic study of the abdomen and pelvis show avid peripheral enhancement of the retroperitoneal mass, whereas the pancreatic tail mass has enhancement that is very similar to spleen. B) Anteroposterior MIP of the abdomen and pelvis from a subsequent Tc-99m sulfur colloid scan, showing normal uptake in the reticuloendothelial system. C) Fusion SPECT/CT image from the Tc-99m sulfur colloid scan shows no significant uptake of radiotracer within the pancreatic tail mass in distinction to the high activity seen within the adjacent spleen, proving the mass is not a splenule.

(Protocol: Splenic CT Protocol, 225 mAs, 120 kV, 0.75 mm slice thickness, 120 mL Omnipaque 350. Protocol: Anteroposterior MIP of the abdomen and pelvis from a subsequent Tc-99m sulfur colloid scan and Fusion SPECT/CT image from the Tc-99m sulfur colloid scan, 5.467 mCi Tc-99m sulfur colloid given IV, Imaging performed at 5 minutes, non-contrast, non-diagnostic CT performed for attenuation correction with 4.5 mm slice thickness.)

DISCUSSION

Solitary fibrous tumors (SFT) are rare spindle cell neoplasms that typically occur in the pleura, mediastinum, and lung[1]. SFTs have been shown to have an age-standardized incidence rate of 1.4 per million, and they typically present in the sixth and seventh decade, affecting both genders equally[2,3]. Although uncommon, SFTs may be found in extrathoracic sites such as the upper respiratory tract and retroperitoneum[4]. On CT SFTs appear as heterogeneously enhancing masses, and on MRI, they may exhibit T1 hypo- or isointensity and heterogeneous T2 hyperintensity[5]. Simple excision is considered curative for benign SFTs and is recommended to prevent malignant transformation and metastasis[6].

Although the utility of FDG PET in the diagnosis and grading of soft-tissue sarcomas is well known[7], little has been written regarding the FDG PET imaging characteristics of SFTs specifically. In one case, a SFT of the pancreas showed no significant FDG uptake[8]. In another case, a parapharyngeal SFT showed heterogeneous uptake of FDG[5]. In this case, we report a patient with two benign extrathoracic SFTs that exhibited low FDG avidity on three PET/CT scans prior to resection.

SFTs are predominantly thoracic, and most information from extrathoracic SFTs are limited to case reports[9]. Historically, SFTs have been classified as “localized mesothelioma”, “fibrous mesothelioma”, “benign mesothelioma”, and “submesothelial fibromas”, although the findings of extrathoracic SFTs discredit mesothelial origin[10]. SFTs are diagnosed histologically with an immunoprofile of positivity for CD34, Bcl-2, and vimentin and negativity for keratin[11]. Malignant SFTs are typically defined as large (>10cm) tumors, with hemorrhage and necrosis, and > 4 mitoses per 10 hpf[12]. Based on this definition, neither of our patient’s lesions met criteria for malignancy. However, as noted above, resection of all SFTs is standard of care to avoid complications due to mass effect on local structures and malignant degeneration seen in 10 to 30% of SFTs[13].

Although SUVs have acknowledged clinical limitations[14], they generally correlate with increasing tumor grade. Schwarzbach et al. calculated the median SUVs for low-grade, intermediate-grade and high-grade soft tissue sarcomas to be 1.3, 2.7 and 4.5, respectively[15]. In addition, the limited data on FDG PET/CT findings in intra-thoracic SFTs indicate that high-grade malignant lesions exhibit higher FDG uptake than benign lesions[16]. Our patient’s lesions patient had SUVs of less than 2.0 at all time points, which correlated well with low ex vivo measures of cell proliferation at histology. Perhaps most importantly, serial volumetric measurements in our case provide in vivo verification the low-grade phenotype of minimally-FDG avid benign extra-thoracic SFT (Figure 1A through E). The tumor doubling times of our patient’s masses were on the order of one year, whereas aggressive mesenchymal sarcomas typically have doubling times on the order of 41 days[17].

This case also illustrates the utility of sulfur colloid SPECT imaging in patients with suspected soft tissue neoplasms of the pancreas. When encountering pancreatic and retroperitoneal neoplasms a number of different tumors should be considered: SFT, high-grade soft tissue sarcoma, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, lymphoma, nerve sheath tumor, retroperitoneal fibrosis, extramedullary hematopoiesis, and splenule. Extra-thoracic SFTs, for example, tend to be well defined and enhance avidly on CT[16]. As a result, they may be difficult to distinguish from other pancreatic neoplasms on conventional imaging. Our patient’s pancreatic tail mass had a much more subtle size increase than the larger retroperitoneal mass (12 mL increase versus 38 mL increase) and exhibited enhancement characteristics similar to spleen on contrast enhanced CT (Figure 2A). However, surgical pathology later revealed that it was the smaller pancreatic tail mass that was invading vital structures; at the time of resection it involved portions of the spleen, pancreas and left kidney, whereas the retroperitoneal mass merely displaced adjacent organs without involving them. Therefore, the information afforded by sulfur colloid SPECT had major implications for surgical planning and patient outcome, permitting appropriate and confident resection of the pancreatic mass with wide margins despite the fact that it strongly resembled a splenule on other imaging modalities.

In conclusion, we report a case of multifocal SFTs of the retroperitoneum and pancreas with low FDG avidity that correlated well with their low-grade in vivo phenotype and ex vivo histology.

TEACHING POINT

Low-grade sarcomas can progress in an indolent fashion even under active FDG PET surveillance, thus highlighting the importance of careful volumetric assessment of even low avidity soft tissue masses on oncologic surveillance protocols - particularly in patients with a history of sarcoma.

Table 1.

Summary table for solitary fibrous tumor (SFT)

| Etiology | Spindle cell neoplasms that typically occur in the pleura, mediastinum, and lung |

| Incidence | 1.4 per million |

| Gender ratio | Affects males and females equally |

| Age predilection | Sixth and seventh decades of life |

| Risk factors | Unknown |

| Treatment | Excision of tumor |

| Prognosis | Early treatment is considered curative, without excision tumor can undergo malignant transformation and metastases. |

| Findings on imaging | Solitary fibrous tumors appear as heterogeneously enhancing masses. On MRI, they may exhibit T1 hypo- or isointensity and heterogeneous T2 hyperintensity. |

Table 2.

Differential table for solitary fibrous tumor (SFT)

| Diagnosis | CT | MRI T1 | MR T2 | Pattern of contrast enhancement | PET |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solitary Fibrous Tumor (Benign variant) | Isodense to muscle | Hypo- or isointensity | Heterogeneous hyperintensity | Avid enhancement peripherally, heterogeneous enhancement centrally. | Low or no FDG avidity |

| High grade soft tissue sarcoma | Variable density, often with low- density necrotic areas | Variable | Heterogeneous hyperintensity | Variable - Often avid, nodular enhancement, sometimes peripheral | Typically high FDG avidity |

| Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma | Hypodense to pancreas | Iso- to hyperintense to pancreas | Iso- to hyperintense to pancreas | Low-attenuating enhancement | Typically high FDG avidity |

| Lymphoma | Typically isodense to muscle | Hypo- or isointensity | Variable | Typically homogenous moderate to avid enhancement | Typically high FDG avidity |

| Nerve sheath tumor | Hypodense to muscle. | Isointense | Hyperintense | Typically avid contrast enhancement. | Typically moderate to high FDG avidity |

| Retroperitoneal fibrosis | Ill-defined soft tissue density surrounding aorta | Hypointensity | Variable | Avid enhancement acutely to non- enhancement chronically | Variable |

| Extramedullary hematopoiesis | Lobulated iso- or hypodense mass | Isointense to muscle | Hyperintense to muscle | Variable enhancement | Low to moderate FDG avidity |

| Splenule* | Isodense to spleen | Isointense to spleen | Isointense to spleen | Similar to spleen | Low to moderate FDG avidity |

ABBREVIATIONS

- CT

computed tomography

- F-18

fluorine-18

- FDG

fludeoxyglucose

- hpf

high powered field

- MIP

maximum intensity projection

- PET

positron emission tomography

- SCC

squamous cell carcinoma

- SFT

solitary fibrous tumor

- SPECT

single-photon emission computed tomography

- SUV

standard uptake value

- Tc-99m

technetium-99m

REFERENCES

- 1.Ali SZ, Hoon V, Hoda S, Heelan R, Zakowski MF. Solitary fibrous tumor. A cytologic-histologic study with clinical, radiologic, and immunohistochemical correlations. Cancer (Cancer Cytopathol) 1997 Apr 25;81(2):116–121. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970425)81:2<116::aid-cncr5>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thorgeirsson T, Isaksson HJ, Hardardottir H, Alfredsson H, Gudbjartsson T. Solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura: an estimation of population incidence. Chest. 2010 Apr;137(4):1005–1006. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Perrot M, Fischer S, Bründler M, Sekine Y, Keshavjee S. Solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002 Jul;74(1):285–293. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03374-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takizawa I, Saito T, Kitamura Y, et al. Primary solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) in the retroperitoneum. Urol Oncol. 2008 May-Jun;26(3):254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wakisaka N, Kondo S, Murono S, Minato H, Furukawa M, Yoshizaki T. A solitary fibrous tumor arising in the parapharyngeal space, with MRI and FDG-PET findings. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2009 Jun;36(3):367–371. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.England DM, Hochholzer L, McCarthy MJ. Localized benign and malignant fibrous tumors of the pleura. A clinicopathologic review of 223 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989 Aug;13(8):640–658. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198908000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ioannidis J, Lau J. 18F-FDG PET for the diagnosis and grading of soft-tissue sarcoma: a meta-analysis. J Nucl Med. 2003 May;44(5):717–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugawara Y, Sakai S, Aono S, et al. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pancreas. Jpn J Radiol. 2010 Jul;28(6):479–482. doi: 10.1007/s11604-010-0453-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vossough A, Torigian DA, Zhang PJ, Siegelman ES, Banner MP. Extrathoracic solitary fibrous tumor of the pelvic peritoneum with central malignant degeneration on CT and MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2005 Nov;22(5):684–686. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crotty TB, Myers JL, Katzenstein AL, Tazelaar HD, Swensen SJ, Churg A. Localized malignant mesothelioma. A clinicopathologic and flow cytometric study. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994 Apr;18(4):357–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanau CA, Miettinen M. Solitary fibrous tumor: histological and immunohistochemical spectrum of benign and malignant variants presenting at different sites. Hum Pathol. 1995 Apr;26(4):440–449. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(95)90147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson LA. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura. Cancer Control. 2006 Oct;13(4):264–269. doi: 10.1177/107327480601300403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park CK, Lee DH, Park JY, Park SH, Kwon KY. Multiple recurrent malignant solitary fibrous tumors: long-term follow-up of 24 years. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011 Apr;91(4):1285–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.08.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lucignani G, Paganelli G, Bombardieri E. The use of standardized uptake values for assessing FDG uptake with PET in oncology: a clinical perspective. Nucl Med Commun. 2004 Jul;25(7):651–656. doi: 10.1097/01.mnm.0000134329.30912.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwarzbach MH, Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss A, Willeke F, et al. Clinical value of [18-F]] fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging in soft tissue sarcomas. Ann Surg. 2000 Mar;231(3):380–386. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200003000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohler M, Clarenbach CF, Kestenholz P, et al. Diagnosis, treatment and long-term outcome of solitary fibrous tumours of the pleura. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007 Sep;32(3):403–408. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malaise EP, Chavaudra N, Tubiana M. The relationship between growth rate, labeling index and histological type of human solid tumors. Eur J Cancer. 1973 Apr;9(4):305–312. doi: 10.1016/0014-2964(73)90099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]