Abstract

A substantial proportion of patients with lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B virus (HBV) show suboptimal virologic response during rescue combination treatment with lamivudine plus adefovir. In this randomized active-control trial, 90 patients with serum HBV DNA levels of >2,000 IU/ml after at least 24 weeks of treatment with lamivudine-plus-adefovir therapy for lamivudine-resistant HBV were randomized to combination treatment with entecavir plus adefovir (ETV+ADV, n = 45) or continuation of lamivudine plus adefovir (LAM+ADV, n = 45) for 52 weeks. At baseline, patients' mean serum HBV DNA level was 4.60 log10 IU/ml (standard deviation [SD], 1.03). All 90 patients completed 52 weeks of treatment. At week 52, the proportion of patients with serum HBV DNA levels of <60 IU/ml, the primary endpoint, was significantly higher in the ETV+ADV group than in the LAM+ADV group (n = 13, 29%, versus n = 2, 4%, respectively; P = 0.004). The mean reduction in serum HBV DNA levels from baseline was significantly greater in the ETV+ADV group than in the LAM+ADV group (−2.2 log10 IU/ml versus −0.6 log10 IU/ml, respectively; P < 0.001). At week 52, additional mutations causing resistance to adefovir or entecavir were analyzed in all patients with detectable HBV DNA by restriction fragment mass polymorphism assays and detected in none of the ETV+ADV group but in 15% of patients in the LAM+ADV group (P = 0.018). Safety and adverse event profiles were similar in the two groups. In conclusion, entecavir-plus-adefovir combination therapy provides superior virologic response and favorable resistance profiles, compared with the continuing lamivudine-plus-adefovir combination, in patients with lamivudine-resistant HBV who fail to respond to lamivudine-plus-adefovir combination therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Ahigh hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA concentration in serum in patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is an independent risk factor for disease progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (8, 14). Reducing HBV DNA to very low or undetectable levels has been linked with reduced risks of disease progression (7, 10, 20, 38), whereas a persistently inadequate or suboptimal virologic response during nucleoside/nucleotide analogue (NA) therapy is a strong risk factor for the emergence of viral resistance and breakthrough, which may lead to disease progression and clinical deterioration (16, 20, 41). Thus, antiviral therapy should aim to suppress HBV replication as completely and rapidly as possible (11, 19, 22).

With the availability of potent NAs, such as entecavir (ETV) and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), suppression of serum HBV DNA to undetectable levels by PCR assays became achievable in most NA treatment-naïve patients without the development of drug-resistant HBV mutants (6, 34). Until recently, however, many patients commenced antiviral treatment with less potent NAs prior to the availability of ETV or TDF, such as lamivudine (LAM), which also has a low genetic barrier to resistance. In patients resistant to LAM, add-on combination therapy with LAM and adefovir (ADV) has resulted in lower rates of virologic breakthrough and additional development of genotypic resistance than has switching to ADV or ETV monotherapy (18, 27) and has been recommended as one of the treatment options (11, 19, 22). Unfortunately, a substantial proportion of patients treated with LAM-plus-ADV combination therapy show a suboptimal virologic response, especially when combination therapy is started at a time of high viral load or after the emergence of mutations causing resistance to both ADV and LAM (13, 18, 27).

For patients who fail to respond to both LAM and ADV, the efficacy of either ETV or TDF monotherapy has been suggested to be inferior in comparison to that in treatment-naïve patients (23, 33, 39), which emphasizes the need for exploration of adequate combination therapy in treatment of multidrug-refractory CHB.

The combination of ETV, a nucleoside analogue, and ADV or TDF, nucleotide analogues, should be a promising rescue treatment for CHB patients with LAM resistance (21, 25). In some countries and for some patients, TDF is not available because of licensing, cost, or tolerability. ETV and ADV have some antiviral efficacy against LAM-resistant HBV with complementary resistance profiles (24, 31). A study in healthy volunteers showed no evidence of a pharmacokinetic interaction between ETV and ADV, allowing both to be safely administered without the need for dose adjustment of either (3). An in vitro study showed modest synergy between these two agents (9). Furthermore, we and others retrospectively demonstrated that this combination treatment was effective in CHB patients with various degrees of resistance (21, 30). Therefore, in this randomized active-control trial, we compared the efficacy of switching to ETV plus ADV with the continuation of LAM plus ADV in patients with LAM-resistant HBV who show a suboptimal response to ongoing treatment with LAM plus ADV.

(This study was presented in part at the 62nd Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, 7 November 2011.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects.

Patients eligible for this study were men and women, aged 16 to 75 years, positive for serum hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg) for at least 6 months and positive or negative for hepatitis B virus e antigen (HBeAg). Inclusion criteria were confirmed mutations in the HBV polymerase gene that confer resistance to LAM (rtM204V/I and/or rtL180M) and a serum HBV DNA concentration of >2,000 IU/ml after combination treatment with LAM (100 mg/day) plus ADV (10 mg/day) for at least 6 months that was ongoing at the time of randomization. Patients were expected to have well-preserved liver function (Child-Pugh-Turcotte score, ≤6) and no history of ascites, variceal bleeding, or encephalopathy.

Patients were excluded if they had previous or current HCC; had received prior treatment with an antiviral agent other than LAM and/or ADV; were coinfected with hepatitis C, hepatitis D, or human immunodeficiency virus; had a serum creatinine concentration of >1.5 mg/dl; were receiving concurrent systemic corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive agents; had a history of alcohol or substance abuse; were pregnant, breastfeeding, or planning to become pregnant; or had other concurrent liver diseases, prior organ transplantation, or a history of malignancy within 3 years.

Study design.

This was a randomized, active-control, open-label, single-center, parallel trial. All eligible patients were enrolled in this study in Asan Medical Center, Seoul, South Korea, between November 2009 and July 2010. Patients were randomized to treatment with ETV (1 mg/day orally) plus ADV (10 mg/day orally) (ETV+ADV group) or to continuation on LAM (100 mg/day orally) plus ADV (10 mg/day orally) (LAM+ADV group) for 52 weeks. There was no interruption in treatment with LAM plus ADV before randomization. Patients were screened within 4 weeks before randomization to determine study eligibility. Eligible patients were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 treatment groups according to simple randomization procedures using a block size of 6 generated by an independent statistician. After the research nurse had obtained the patient's consent, she telephoned the statistician, who was independent of the recruitment process, for allocation consignment. Randomized patients were evaluated at baseline and at weeks 4, 12, 24, 36, and 52. At each visit, patients were evaluated for compliance with study medication (checked with returned pill count) and adverse events. Hematology, biochemistry, and prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (INR) were assessed. HBV DNA level was measured at baseline and at weeks 12, 24, 36, and 52, using a real-time PCR assay (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL) with a linear dynamic detection range of 15 to 1 × 109 IU/ml. Restriction fragment mass polymorphism (RFMP) assays of the HBV genome were performed to detect ADV resistance mutations at baseline and at week 52 and ETV resistance mutations at week 52, as described previously (12). Because over 98% of South Korean patients with CHB have HBV genotype C (1), HBV genotype was not determined. HBeAg and anti-HBe were assessed at baseline and at week 52, using commercially available enzyme immunoassays (Abbott Laboratories). The upper limit of normal (ULN) alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was defined as 30 IU/liter for men and 19 IU/liter for women.

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and in accordance with good clinical practice and local regulatory requirements. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. This study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01023217 (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01023217).

Study endpoints.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of patients in each treatment group who achieved virologic response (serum HBV DNA concentration of <60 IU/ml) at week 52. We favored the use of this level of HBV DNA for the comparability of the results with other studies (15). Secondary efficacy endpoints were changes in serum HBV DNA concentrations over time, the proportion of patients with normal ALT, HBeAg loss, and resistance mutations to ADV and ETV at week 52.

Statistical analysis.

The planned sample size of 45 patients per group had an 85% power to demonstrate the superiority of ETV plus ADV compared with LAM plus ADV for the primary endpoint (HBV DNA level of <60 IU/ml at week 52), with a two-sided 5% significance level, assuming a 33% success rate for the LAM+ADV group (13, 40) and a 65% success rate for the ETV+ADV group (21, 30) and taking into account a dropout rate of up to 5%. This sample size would also provide 100% power to demonstrate a between-group difference in mean HBV DNA concentrations at week 52 of 1.0 log10 IU/ml, assuming a within-group standard deviation (SD) of 1.0 log10 IU/ml and a two-sided significance level of 5%.

The primary analysis set for efficacy and safety analyses was defined as all randomized patients who received at least 1 dose of study medication. Patients who discontinued the study prior to week 52 were considered failures for all antiviral endpoints after the time of discontinuation.

Between-group comparisons of continuous variables were determined using independent t tests, and categorized variables were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL), and R version 2.13.2 (http://cran.r-project.org/). A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of patients.

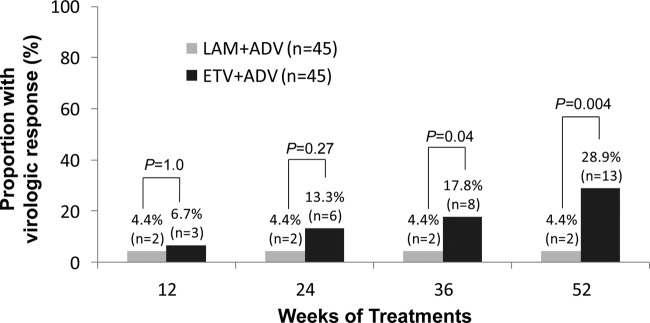

Ninety-three patients were screened from November 2009 to July 2010, and 90 were randomized (45 in each group). All patients completed 52 weeks of treatment, and no patient was lost to follow-up during 52 weeks of treatment after randomization; thus, data from all 90 patients randomized were available for the intention-to-treat analysis (Fig. 1). Participants attended clinic visits at the time of screening at Asan Medical Center, Seoul, South Korea.

Fig 1.

Flow diagram of a randomized trial comparing a switch to an entecavir (ETV)-plus-adefovir (ADV) combination with continuation of lamivudine (LAM)-plus-ADV combination therapy in LAM-resistant chronic hepatitis B patients with suboptimal response to LAM-plus-ADV combination therapy.

The two treatment groups were well balanced for baseline characteristics (Table 1). Twenty-seven (30%) patients had cirrhosis with well-preserved liver function. Overall, 80 (88.9%) patients were HBeAg positive. The median serum HBV DNA concentration of study patients was 4.51 log10 IU/ml. The median duration of LAM-plus-ADV treatment prior to randomization was 15 months. At baseline, all patients had LAM resistance mutations, including 64 (71.1%) with rtM204V/I plus rtL180M, 25 (27.8%) with rtM204V/I (25, 27.8%), and 1 (1.1%) with rtA181T plus rtL180M. Nineteen (21.1%) also had ADV resistance mutations, including 11 (12.2%) with rtA181V/T plus rtN236T and 8 (8.9%) with rtA181V/T.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study patientsa

| Characteristic | Value for patient group (n) |

P valuec | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (90) | ETV+ADV (45) | LAM+ADV (45) | ||

| Age, mean ± SD (yr) | 46.9 ± 11.5 | 44.9 ± 11.4 | 48.8 ± 11.4 | 0.10 |

| Male gender, no. (%) | 67 (74.4) | 33 (73.3) | 34 (75.6) | 0.81 |

| Serum ALT, median (IQR) (IU/liter) | 29 (21-46) | 28 (19-40) | 33 (25-47) | 0.40 |

| Serum total bilirubin, median (IQR) (mg/dl) | 1.0 (0.7-1.2) | 0.9 (0.7-1.2) | 1.0 (0.8-1.25) | 0.07 |

| Serum albumin, median (IQR) (g/dl) | 4.3 (4.1-4.4) | 4.3 (4.1-4.4) | 4.3 (4.2-4.5) | 0.61 |

| Serum creatinine, median (IQR) (mg/dl) | 0.9 (0.8-1.0) | 0.9 (0.8-1.0) | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) | 0.10 |

| INR, median (IQR) | 1.01 (0.98-1.06) | 1.01 (0.98-1.05) | 1.02 (0.98-1.07) | 0.36 |

| Cirrhosis,b no. (%) | 27 (30.0) | 14 (31.1) | 13 (28.9) | 0.82 |

| HBeAg positivity, no. (%) | 80 (88.9) | 39 (86.7) | 41 (91.1) | 0.50 |

| Serum HBV DNA, median (IQR) (log10 IU/ml) | 4.51 (3.74-5.19) | 4.40 (3.59-5.18) | 4.60 (3.93-5.25) | 0.72 |

| Prior LAM+ADV therapy, median (IQR) (mo) | 15 (6-39) | 12 (7-39) | 17 (6-37) | 0.22 |

| LAM resistance mutation, no. (%) | 90 (100) | 45 (100) | 45 (100) | 0.64 |

| rtM204V/I + rtL180M | 64 (71.1) | 31 | 33 | |

| rtM204V/I | 25 (27.8) | 14 | 11 | |

| rtA181T + rtL180M | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 1 | |

| ADV resistance mutation, no. (%) | 19 (21.1) | 7 (15.6) | 12 (26.7) | 0.36 |

| rtA181T,V + rtN236T | 3 (3.3) | 0 | 3 | |

| rtA181T + rtN236T | 5 (5.6) | 2 | 3 | |

| rtA181V + rtN236T | 3 (3.3) | 3 | 0 | |

| rtA181T | 5 (5.6) | 1 | 4 | |

| rtA181V | 3 (3.3) | 1 | 2 | |

Abbreviations: ETV+ADV, entecavir (1 mg/day)-and-adefovir (10 mg/day) combination therapy group; LAM+ADV, lamivudine (100 mg/day)-and-adefovir (10 mg/day) combination therapy group; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; INR, international normalized ratio; IQR, interquartile range.

Cirrhosis was diagnosed by the identification of liver surface nodularity with splenomegaly on ultrasonography.

P value for difference between the ETV+ADV and LAM+ADV groups.

Virologic response.

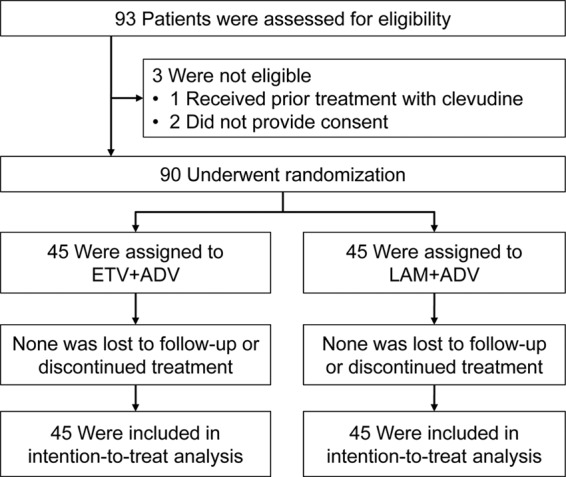

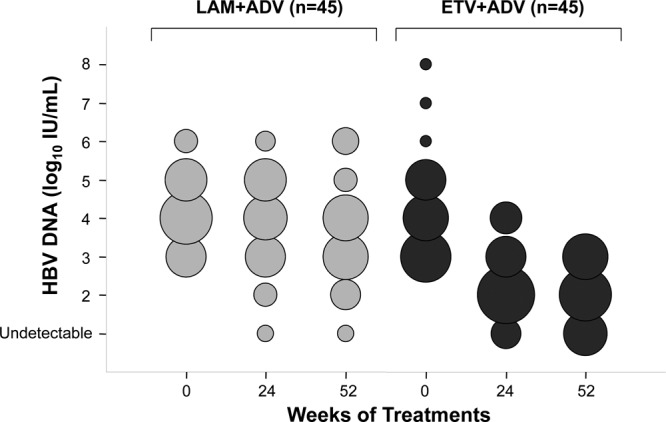

HBV DNA concentrations in the ETV+ADV group declined continuously during treatment, whereas viral loads in the LAM+ADV group remained distributed over a wide range throughout treatment (Fig. 2). The number of patients who achieved virologic response (serum HBV DNA concentration of <60 IU/ml) gradually increased in the ETV+ADV group during treatment with 13 (28.9%) patients at week 52 (Fig. 3). In contrast, only 2 patients (4.4%) in the LAM+ADV group showed a virologic response from week 12 to week 52. The primary efficacy endpoint, the proportion of patients who achieved HBV DNA concentrations of <60 IU/ml at week 52, differed significantly between the two groups (28.9% versus 4.4%, respectively; P = 0.004) (Table 2 and Fig. 3).

Fig 2.

Distribution of patients according to serum HBV DNA concentrations through week 52 by study visit and treatment group. The diameters of the circles are proportional to the numbers of patients with specified HBV DNA concentrations; the numbers represented by the circles in each column total 45. The log HBV DNA concentrations indicated on the y axis reflect all observations within that exponent.

Fig 3.

Proportion of patients with virologic response (serum HBV DNA concentration of <60 IU/ml) by study visit and treatment group.

Table 2.

Virologic, biochemical, and serologic responses and genotypic resistance surveillance at week 52a

| Endpoint | Value for patient group (n) |

Differenced (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETV+ADV (45) | LAM+ADV (45) | |||

| Serum HBV DNA concn of <60 IU/ml, no. (%) | 13 (28.9) | 2 (4.4) | 24.5 (10.01 to 39.70) | 0.004 |

| Reductions in HBV DNA, mean ± SD (log10 IU/ml) | 2.24 ± 1.30 | 0.64 ± 0.83 | 1.61 (1.15 to 2.06) | <0.001 |

| Residual HBV DNA level, mean ± SD (log10 IU/ml) | 2.32 ± 1.23 | 4.00 ± 1.40 | −1.68 (−1.13 to −2.24) | <0.001 |

| Normal ALT,b no. (%) | 26 (57.8) | 20 (44.4) | 13.4 (−7.26 to 32.84) | 0.292 |

| HBeAg loss, no. (%) | 2/39 (5.1) | 0/41 (0) | 5.1 (−3.66 to 16.88) | 0.235 |

| Resistance mutation to ADV or ETV,c no. (%) | 3 (6.7) | 15 (33.3) | −26.6 (−42.4 to −10.9) | 0.003 |

| Retention of baseline ADV mutations, no. positive/total no. (%) | 1/7 (14.3) | 10/12 (83.3) | −69.0 (−89.2 to −23.7) | 0.006 |

| rtA181T,V + rtN236T, no. | 0 | 1 | ||

| rtA181T + rtN236T, no. | 0 | 5 | ||

| rtA181V + rtN236T, no. | 1 | 0 | ||

| rtA181T, no. | 0 | 2 | ||

| rtA181V, no. | 0 | 2 | ||

| Additional emergence of ADV mutations, no. positive/total no. (%) | 0/38 (0) | 5/33 (15.2) | −15.2 (−30.9 to −5.24) | 0.018 |

| rtA181T + rtN236T, no. | 0 | 1 | ||

| rtA181V + rtN236T, no. | 0 | 2 | ||

| rtA181T, no. | 0 | 1 | ||

| rtN236T, no. | 0 | 1 | ||

| Retention of baseline ETV mutations, no. (%) | 2 (4.4) | NA | NA | |

| rtT184A, no. | 1 | |||

| rtM250L, no. | 1 | |||

| Additional emergence of ETV mutations, no. | 0 | NA | NA | |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; CI, confidence interval.

The upper limit of normal ALT was defined as 30 IU/liter for men and 19 IU/liter for women.

Detection of resistance mutations by restriction fragment mass polymorphism analysis.

The difference estimate was calculated for the ETV+ADV group compared with the LAM+ADV group.

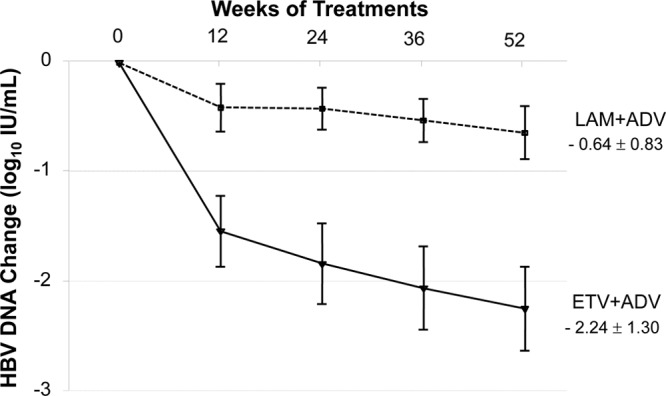

The mean reduction of serum HBV DNA concentrations from baseline to week 52 was significantly greater in the ETV+ADV than in the LAM+ADV group (−2.24 log10 IU/ml versus −0.64 log10 IU/ml, respectively; P < 0.001) (Table 2 and Fig. 4). Patients in the ETV+ADV group experienced an initial rapid reduction in viral load, of 1.5 log10 IU/ml at 12 weeks, with an additional steady reduction between weeks 12 and 52. The between-group differences in HBV DNA changes were significant from week 12 through week 52 (P < 0.05). The residual mean HBV DNA concentrations at week 52 were significantly lower in the ETV+ADV than in the LAM+ADV group (2.32 log10 IU/ml versus 4.00 log10 IU/ml, respectively; P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Fig 4.

Mean change in serum HBV DNA levels from baseline over 52 weeks by study visit and treatment group. The error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

The number of patients with virologic nonresponse, defined as a <1-log10-IU/ml reduction in HBV DNA concentration from baseline at week 24, was significantly lower in the ETV+ADV than in the LAM+ADV group (10 [22.2%] versus 39 [86.7%], respectively; P < 0.001). Medication compliance was evaluated by checking returned pill count at each visit, and noncompliance was suspected in none of the patients. Virologic breakthrough (≥1-log10-IU/ml increase in serum HBV DNA from nadir during therapy) was observed in 1 patient in the LAM+ADV group who had ADV resistance mutations (rtA181V/T plus rtN236T) at baseline but in none of the patients in the ETV+ADV group.

In univariate and multivariate analyses, only baseline HBV DNA concentration (P < 0.01) and treatment with ETV+ADV (P < 0.01) were significant predictors of virologic response. The presence of ADV resistance mutations at baseline was not significantly associated with virologic response at week 52 (P = 0.91).

Biochemical and serologic responses.

The proportions of patients with normal serum ALT concentrations at week 52 did not differ significantly between the ETV+ADV and LAM+ADV groups (57.8% versus 44.4%, respectively; P = 0.292) (Table 2). Among patients who were HBeAg positive at baseline, 5.1% (2/39) in the ETV+ADV group and 0% (0/41) in the LAM+ADV group became HBeAg negative at week 52 (P = 0.235; Table 2). No patient achieved HBeAg seroconversion at week 52.

Resistance surveillance.

Paired baseline and week 52 samples from all study patients with detectable serum HBV DNA were genotypically analyzed for ADV resistance mutations (Table 2). Among those with one or more ADV resistance mutations at baseline, 14.3% (1/7) in the ETV+ADV group and 83.3% (10/12) in the LAM+ADV group retained these mutations at week 52 (P = 0.006). Among those who did not have ADV resistance mutations at baseline, none (0/38) in the ETV+ADV group but 15.2% (5/33) in the LAM+ADV group additionally developed ADV resistance substitutions at week 52 (P = 0.018). Four of these five patients in the LAM+ADV group showed virologic nonresponse at week 24 and inadequate virologic response at week 52.

Genotypic ETV resistance mutations were analyzed in all patients in the ETV+ADV group at week 52 and were found in 2 (4.4%) patients (Table 2). Genotypic analysis of paired baseline samples of these patients showed that, despite being ETV naïve, they harbored the same ETV resistance mutations in the baseline viral population. These results were confirmed by sequencing analysis as well as the RFMP method. Each of these patients showed virologic nonresponse at week 24 and inadequate virologic response at week 52, respectively.

Overall, the number of patients with detectable ADV or ETV resistance mutations at week 52 was significantly lower in the ETV+ADV than in the LAM+ADV group (3 [6.7%] versus 15 [33.3%], respectively; P = 0.003) (Table 2).

Safety.

Adverse events were similar in the two groups (Table 3). There were 2 serious adverse events in each group. One patient in the ETV+ADV group experienced sudden left-sided sensorineural hearing loss, which resolved with systemic corticosteroid therapy on continued ETV-plus-ADV treatment. Another patient in the ETV+ADV group received surgical treatment of a papillary thyroid carcinoma, which had been diagnosed before enrollment in the study but was not reported by the patient at screening. One patient in the LAM+ADV group received surgical treatment for an intervertebral disc herniation, and a second patient experienced a rib fracture. All adverse events and serious adverse events were considered unrelated to the study medication. No patient required dose interruption or discontinuation of treatment due to an adverse event. No patient experienced ALT flare (>10× upper limit of normal [ULN]), an increase in serum creatinine concentration of ≥0.5 mg/dl, or a serum phosphorus level of <1.5 mg/dl during the treatment period.

Table 3.

Summary of safety

| Characteristic | Value for patient group (n) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ETV+ADV (45) | LAM+ADV (45) | ||

| Any adverse event, no. (%) | 23 (51.1) | 22 (48.9) | 0.83 |

| Serious adverse event, no. (%) | 2 (4.4) | 2 (4.4) | 1.00 |

| Dose reduction of study medication, no. | 0 | 0 | |

| Discontinuation of study medication, no. | 0 | 0 | |

| ALT flarea | 0 | 0 | |

| Increase in serum creatinineb | 0 | 0 | |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) at wk 52, median (range) | 0.9 (0.6-1.5) | 0.9 (0.6-1.3) | 0.29 |

| Serum phosphorus (mg/dl) at wk 52, median (range) | 3.4 (1.6-4.6) | 3.3 (2.1-4.4) | 0.40 |

| Serum lactic acid (mmol/liter) at wk 52, median (range) | 1.3 (0.4-4.0) | 1.2 (0.5-2.7) | 0.63 |

ALT of >10× ULN.

Value of ≥0.5 mg/dl above baseline.

DISCUSSION

The results of this trial clearly show that treatment for 52 weeks with the combination of ETV plus ADV significantly suppressed HBV replication and was not associated with the development of additional resistance mutations in patients with LAM-resistant HBV who showed suboptimal responses to LAM-plus-ADV combination therapy. In contrast, continuation of the combination of LAM plus ADV provided little antiviral benefit and increased the rate of emergence of additional resistance mutations to ADV.

The combination of LAM plus ADV has been recommended as one of the treatment options for patients resistant to LAM (11, 19, 22). Compared with ADV monotherapy, this combination therapy may reduce the development of resistance mutations to ADV (18, 27). However, because continued LAM has no effect on virologic response in patients with LAM-resistant HBV, the combination of LAM plus ADV does not result in increased antiviral efficacy compared with ADV monotherapy (24, 27). Since ADV has modest potency in suppressing HBV DNA replication (11), a substantial proportion of patients show inadequate or suboptimal virologic response during treatment with LAM plus ADV (17, 27). Response to LAM plus ADV was especially reduced in patients with high viral load and mutations causing resistance to both drugs (e.g., rtA181V/T with or without rtN236T) at the initiation of treatment (4, 13, 17).

ETV monotherapy has also been assessed in patients with antiviral drug-resistant HBV. In patients with LAM-refractory CHB, treatment with ETV at 1.0 mg for 48 weeks was associated with virologic, histologic, serologic, and biochemical improvements (5, 31). ETV has also proven to be effective in suppressing ADV resistance mutations in vitro (13, 26). Since LAM-resistant HBV has partial resistance to ETV, however, its likelihood of achieving a virologic response is lower in patients with LAM-resistant HBV than in LAM-naïve patients (5, 31). The efficacy of ETV is further decreased in ADV-refractory CHB patients with preexisting LAM resistance (29, 33). In addition, genotypic resistance to ETV emerged frequently during long-term treatment of patients with LAM resistance (31, 37). These findings indicate that ETV monotherapy is not optimal for the treatment of LAM-refractory HBV and emphasize the importance of appropriate combination therapies in patients with multidrug-resistant or -refractory HBV.

Ideally, each NA used in combination regimens to treat drug-resistant CHB should have antiviral efficacy as monotherapy and different mechanisms of action without cross-resistance profiles. Although each was not optimally effective as monotherapy, ETV and ADV have demonstrated efficacy in patients with LAM-resistant HBV (24, 31) and have complementary resistance profiles (26), explaining our finding that the combination of ETV plus ADV resulted in a higher rate of virologic response in patients with LAM-resistant HBV who failed LAM plus ADV.

Importantly, we found that continuing the combination of LAM plus ADV with suboptimal response offers little antiviral benefit to patients with LAM-resistant HBV and promotes the emergence of multidrug-resistant strains of HBV. As much as 87% of patients who continued on LAM plus ADV demonstrated virologic nonresponse at week 24, and about 78% showed inadequate virologic responses at week 52. Furthermore, 15% (5/33) of the patients without ADV resistance mutations at baseline developed resistance mutations to ADV at week 52, which was associated with virologic nonresponse on continued LAM plus ADV in most of those patients. These findings indicate that, even with an add-on combination therapeutic strategy, multidrug-resistant strains of HBV may arise if complete viral suppression is not achieved rapidly. The efficacy of any subsequent rescue therapy would further decrease as the number of genotypic resistance mutations increases (21). Thus, rescue therapy should be implemented as early as possible for patients with LAM-resistant HBV who show a suboptimal response with LAM plus ADV, before these patients develop mutations causing resistance to multiple drugs.

The HBeAg loss rate in this trial was quite low, 5% in the ETV+ADV group, suggesting that this heavily pretreated population is particularly refractory to serologic response. Although the mechanism is unclear, HBeAg seroconversion has been reported to be less common in patients with LAM-resistant mutations than in those with wild-type HBV, regardless of the rescue therapy (5, 24, 32).

Emergence of HBV mutants resistant to ADV or ETV and safety are the major concerns during long-term treatment with the combination of ETV plus ADV. Two patients in our ETV+ADV group harbored ETV resistance mutations at week 52 without virologic breakthrough. However, an analysis of paired baseline serum samples of these patients unexpectedly identified isolates with the same substitutions associated with ETV resistance at baseline. Since these patients had never been exposed to ETV prior to entering this trial, these findings indicate that LAM therapy selected for ETV resistance substitutions prior to ETV therapy. These findings are consistent with previous reports, which showed that about 6% of patients with LAM resistance also harbored ETV resistance mutations at baseline (36, 37). Interestingly, we observed no additional emergence and a marked reduction in detectable ADV resistance mutations during ETV-plus-ADV therapy. This may be due to ADV-resistant HBV mutants being susceptible to ETV, as shown both in vitro and in vivo (26, 28, 33). Overall, no additional genotypic resistance mutations to ADV or ETV developed during ETV-plus-ADV combination therapy for up to 52 weeks. The combination of ADV with either ETV or LAM was generally well tolerated during the 52-week treatment period. No patient required dose reduction or discontinuation due to an adverse event. There was no significant change in serum creatinine and serum phosphorus concentrations.

This study has some limitations. First, this was an open-label study without placebo control or blinding. Although objective endpoints (virological and biochemical) were used and drug adherence was ascertained, the lack of blinding might have affected the extra attention of the study patients or the investigators in reporting adverse events. Second, ETV resistance might develop several years later in the background of LAM resistance. In this regard, the duration of this study (52 weeks) was relatively short. Thus, longer duration of follow-up assessment is planned. Last, although our study demonstrated that treatment with ETV plus ADV significantly suppressed HBV replication in LAM-resistant CHB patients who failed LAM plus ADV, the efficacy of ETV plus ADV was not sufficient to achieve virologic response in all patients. This is likely due to the relatively low antiviral potency of ADV, suggesting that ADV should be replaced by another drug with a similar resistance profile but a higher potency against LAM-resistant mutants. TDF is much more potent than ADV and effective for LAM-resistant HBV strains but has controversial efficacy for patients with prior ADV failure or ADV-resistant HBV as monotherapy (2, 23, 35, 39). Thus, TDF would be a promising candidate for combination with ETV in patients with multidrug-resistant HBV (25).

In summary, this randomized trial demonstrated that 52 weeks of treatment with ETV plus ADV resulted in a significantly higher rate of virologic response, a significantly greater reduction in serum HBV DNA concentration, a significantly lower rate of inadequate virologic response, no occurrence of additional resistance mutations, and safety profiles similar to those of the continuation of LAM plus ADV in patients with LAM-resistant HBV who failed treatment with LAM plus ADV. In contrast, the continuation of LAM plus ADV provided little antiviral benefit to these patients and increased the rate of emergence of additional ADV resistance mutations.

In conclusion, these results suggest that CHB patients with LAM-resistant HBV and a suboptimal response to LAM-plus-ADV therapy should be switched as soon as possible to antiviral agents with higher potency, and the combination of ETV plus ADV would be a viable option for patients who are not able to use TDF for any reason.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Seungbong Han and Sung-Eun Choi for their excellent help in statistical analyses. We are indebted to Heung-Bum Oh and Sun-Young Ko and GeneMatrix Inc. for their help in tests for HBV resistance mutations.

Y.-S. Lim was responsible for the concept and design of the study; the acquisition, analysis, and the interpretation of the data; and the drafting of the manuscript. J.-Y. Lee was involved in the acquisition of the data and administrative and technical support. D. Lee, J. H. Shim, H. C. Lee, and Y. S. Lee helped with the acquisition of the data and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. D. J. Suh supervised the study and provided critical revision of the manuscript.

Y.-S.L. has received grant support from GlaxoSmithKline and Bristol-Myers Squibb, consulting fees from Roche, and lecture fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Merck Sharp & Dohme. J.H.S., H.C.L., Y.S.L., and D.J.S. have received consulting fees and lecture fees from GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, and Merck Sharp & Dohme. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose relevant to the manuscript.

This study was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb, which also provided the study drugs (lamivudine, adefovir, and entecavir). Bristol-Myers Squibb was permitted to review the manuscript and suggest changes but had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The final decision on content was exclusively retained by the authors.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 19 March 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Bae SH, et al. 2005. Hepatitis B virus genotype C prevails among chronic carriers of the virus in Korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 20:816–820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berg T, et al. 2010. Tenofovir is effective alone or with emtricitabine in adefovir-treated patients with chronic-hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology 139:1207–1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bifano M, et al. 2007. Absence of a pharmacokinetic interaction between entecavir and adefovir. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 47:1327–1334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Buti M, et al. 2007. Viral genotype and baseline load predict the response to adefovir treatment in lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B patients. J. Hepatol. 47:366–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chang TT, et al. 2005. A dose-ranging study of the efficacy and tolerability of entecavir in lamivudine-refractory chronic hepatitis B patients. Gastroenterology 129:1198–1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chang TT, et al. 2010. Entecavir treatment for up to 5 years in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 51:422–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chang TT, et al. 2010. Long-term entecavir therapy results in the reversal of fibrosis/cirrhosis and continued histological improvement in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 52:886–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen CJ, et al. 2006. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA 295:65–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Delaney WE, IV, Yang H, Miller MD, Gibbs CS, Xiong S. 2004. Combinations of adefovir with nucleoside analogs produce additive antiviral effects against hepatitis B virus in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3702–3710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Di Marco V, et al. 2004. Clinical outcome of HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B in relation to virological response to lamivudine. Hepatology 40:883–891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. European Association for the Study of the Liver 2009. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B. J. Hepatol 50:227–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Han KH, et al. 2011. Comparison of multiplex restriction fragment mass polymorphism and sequencing analyses for detecting entecavir resistance in chronic hepatitis B. Antivir. Ther. 16:77–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Heo NY, et al. 2010. Lamivudine plus adefovir or entecavir for patients with chronic hepatitis B resistant to lamivudine and adefovir. J. Hepatol. 53:449–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Iloeje UH, et al. 2006. Predicting cirrhosis risk based on the level of circulating hepatitis B viral load. Gastroenterology 130:678–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Keeffe EB, et al. 2007. Report of an international workshop: roadmap for management of patients receiving oral therapy for chronic hepatitis B. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5:890–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lai CL, et al. 2007. Telbivudine versus lamivudine in patients with chronic hepatitis B. N. Engl. J. Med. 357:2576–2588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lampertico P, et al. 2005. Adefovir rapidly suppresses hepatitis B in HBeAg-negative patients developing genotypic resistance to lamivudine. Hepatology 42:1414–1419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lampertico P, et al. 2007. Low resistance to adefovir combined with lamivudine: a 3-year study of 145 lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B patients. Gastroenterology 133:1445–1451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liaw YF, et al. 2008. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2008 update. Hepatol. Int. 2:263–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liaw YF, et al. 2004. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 351:1521–1531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lim YS, et al. 2012. Entecavir plus adefovir combination treatment for chronic hepatitis B patients after failure of nucleoside/nucleotide analogues. Antivir. Ther. 17:53–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lok AS, McMahon BJ. 2009. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology 50:661–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Patterson SJ, et al. 2011. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate rescue therapy following failure of both lamivudine and adefovir dipivoxil in chronic hepatitis B. Gut 60:247–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peters MG, et al. 2004. Adefovir dipivoxil alone or in combination with lamivudine in patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology 126:91–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Petersen J, et al. 2012. Entecavir plus tenofovir combination as rescue therapy in pre-treated chronic hepatitis B patients: an international multicenter cohort study. J. Hepatol. 56:520–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Qi X, Xiong S, Yang H, Miller M, Delaney WE., IV 2007. In vitro susceptibility of adefovir-associated hepatitis B virus polymerase mutations to other antiviral agents. Antivir. Ther. 12:355–362 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rapti I, Dimou E, Mitsoula P, Hadziyannis SJ. 2007. Adding-on versus switching-to adefovir therapy in lamivudine-resistant HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 45:307–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reijnders JG, et al. 2010. Antiviral effect of entecavir in chronic hepatitis B: influence of prior exposure to nucleos(t)ide analogues. J. Hepatol. 52:493–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Reijnders JG, Pas SD, Schutten M, de Man RA, Janssen HL. 2009. Entecavir shows limited efficacy in HBeAg-positive hepatitis B patients with a partial virologic response to adefovir therapy. J. Hepatol. 50:674–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schollmeyer J, et al. 2008. Switching to adefovir plus entecavir is effective and leads to strong viral suppression in HBV mono-infected patients failing sequential or combination therapy with lamivudine and adefovir. Hepatology 48:721A [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sherman M, et al. 2008. Entecavir therapy for lamivudine-refractory chronic hepatitis B: improved virologic, biochemical, and serology outcomes through 96 weeks. Hepatology 48:99–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sherman M, et al. 2006. Entecavir for treatment of lamivudine-refractory, HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology 130:2039–2049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shim JH, et al. 2009. Efficacy of entecavir in patients with chronic hepatitis B resistant to both lamivudine and adefovir or to lamivudine alone. Hepatology 50:1064–1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Snow-Lampart A, et al. 2011. No resistance to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate detected after up to 144 weeks of therapy in patients monoinfected with chronic hepatitis B virus. Hepatology 53:763–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tan J, et al. 2008. Tenofovir monotherapy is effective in hepatitis B patients with antiviral treatment failure to adefovir in the absence of adefovir-resistant mutations. J. Hepatol. 48:391–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tenney DJ, et al. 2007. Two-year assessment of entecavir resistance in lamivudine-refractory hepatitis B virus patients reveals different clinical outcomes depending on the resistance substitutions present. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:902–911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tenney DJ, et al. 2009. Long-term monitoring shows hepatitis B virus resistance to entecavir in nucleoside-naive patients is rare through 5 years of therapy. Hepatology 49:1503–1514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Toy M, Veldhuijzen IK, de Man RA, Richardus JH, Schalm SW. 2009. Potential impact of long-term nucleoside therapy on the mortality and morbidity of active chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 50:743–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. van Bommel F, et al. 2010. Long-term efficacy of tenofovir monotherapy for hepatitis B virus-monoinfected patients after failure of nucleoside/nucleotide analogues. Hepatology 51:73–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vigano M, Lampertico P, Facchetti F, Lunghi G, Colombo M. 2008. Failure of adefovir 20 mg to improve suboptimal response in lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B patients treated with adefovir 10 mg and lamivudine. J. Viral Hepat. 15:922–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yuen MF, et al. 2001. Factors associated with hepatitis B virus DNA breakthrough in patients receiving prolonged lamivudine therapy. Hepatology 34:785–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]