Abstract

The interaction between colistin and tigecycline against eight well-characterized NDM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae strains was studied. Time-kill methodology was employed using a 4-by-4 exposure matrix with pharmacokinetically achievable free drug peak, trough, and average 24-h serum concentrations. Colistin sulfate and methanesulfonate alone showed good early bactericidal activity, often with subsequent regrowth. Tigecycline alone had poor activity. Addition of tigecycline to colistin does not produce increased bacterial killing; instead, it may cause antagonism at lower concentrations.

TEXT

New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase 1 (NDM-1)-producing Enterobacteriaceae strains are being reported all over the world (10, 11, 13). The chemotherapeutic options for treating NDM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae infection are limited (5). Colistin and tigecycline (TGC) are both agents for which many strains still have MICs below the clinical breakpoint. Tigecycline and colistin act on bacterial cells by different mechanisms: tigecycline by inhibition of protein synthesis and colistin on the outer cell membrane. Also, tigecycline is bacteriostatic by nature, whereas colistin is bactericidal. Therefore, there is a potential scope for both antagonism and synergy. Also, there are compelling reasons why clinicians may choose to use these drugs in combination, especially given the recent controversies regarding the efficacy and safety of tigecycline monotherapy (1, 14).

We studied the bactericidal activities of tigecycline (TGC), colistin sulfate (CS), and colistin methanesulfonate (CMS) alone as well as in various combinations against NDM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae.

The bactericidal activities of TGC, CS, and CMS were assessed using time-kill methodology (12). For each antimicrobial agent, we used pharmacokinetically achievable free drug serum concentrations. We used the following concentrations (mg/liter) reflecting peak (Cmax), 24-h average (Css), and trough (Cmin) concentrations: 0.17, 0.04, and 0.025, respectively, for TGC (4); 0.29, 0.16, and 0.1, respectively, for CS (3, 9); and 8.5, 2.7, and 2.1, respectively, for CMS (2, 6, 7). A 4-by-4 drug exposure matrix of TGC with CS and CMS was used along with an antibiotic-free growth control (GC).

Eight well-characterized strains of NDM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae (2 of Escherichia coli, 2 of Klebsiella oxytoca, and 4 of Klebsiella pneumoniae) stored at −70°C were selected for the study. The MICs for all the isolates were measured by the gradient strip method using the Etest (bioMérieux). The tigecycline MICs of the two E. coli strains were 0.25 and 0.38 mg/liter, and both K. oxytoca strains had MICs of 0.25 mg/liter. Of the four K. pneumoniae strains, two had a tigecycline MIC of 0.38 mg/liter and the remaining two strains had MICs of 1.5 and 3.0 mg/liter. The colistin MIC of both E. coli strains was 0.38 mg/liter, and the MICs of the two K. oxytoca strains were 0.094 and 0.125 mg/liter. Two out of the four K. pneumoniae strains had a colistin MIC of 0.38 mg/liter, and the remaining two strains had MICs of 0.125 and 0.094 mg/liter.

Overnight cultures of isolates were inoculated into Muller-Hinton broth containing the antimicrobials to yield a final inoculum of 106 CFU/ml. The broths were sampled neat, diluted by 103, and plated onto nutrient agar by using a spiral plater (Don Whitley Scientific, Yorkshire, United Kingdom) at 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24-hour time points. Viable counts were read manually after overnight incubation at 37°C.

Time-kill curves (TKC) were drawn by plotting log10 CFU/ml against time (h) using the software package GraphPad Prism 4.0 (San Diego, CA). A total of 256 (8 × 32) TKC were recorded in the study. Area-under-bacterial-kill curves (AUBKC) were calculated (8) and compared between different antimicrobial agents and their combinations by a paired-sample t test (SPSS version 18; Chicago, IL).

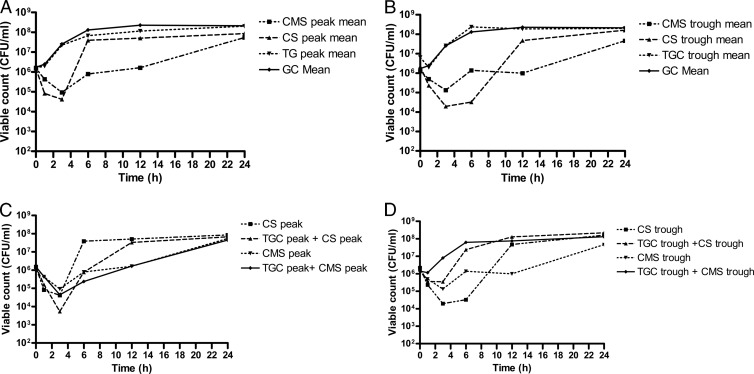

The mean TKC of individual antimicrobial agents and their combinations at different concentrations are shown in Fig. 1A to D.

Fig 1.

Antibacterial activities of tigecycline, colistin sulfate, and colistin methanesulfonate against NDM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae at free peak concentrations of individual drugs (A), free trough concentrations of individual drugs (B), combinations of peak concentrations (C), and combinations of trough concentrations (D).

AUBKC for TGC showed a modest but significant inhibitory effect only at Cmax of 180 ± 13.33, compared with the GC value of 191 ± 4.4 (P < 0.008; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.3 to 18.1). In contrast, both CMS and CS showed better antimicrobial activity at all concentrations (Table 1). CMS produced better killing at all concentrations (Cmax, Css, and Cmin) than did CS (88 ± 39.8, 115 ± 42.4, and 111 ± 38.7 versus 121 ± 41.4, 122 ± 35.6, and 134 ± 33.6, respectively), and this was statistically significant at Cmax (P < 0.001; 95% CI, 18.38 to 49.8). Also, both CS and CMS showed bactericidal activity with a mean log drop in viable counts of 3.3 ± 1.2 and 3.4 ± 1.4 at 3 h and 2.4 ± 2.1 and 3.3 ± 1.6 at 6 h, respectively, at peak concentrations. The bactericidal effect was inversely proportional to the colistin MIC (data not shown).

Table 1.

AUBKC for both individual drugs and combinations of tigecycline, colistin sulfate, and colistin methanesulfonate

| Second drug and concn (mg/liter) | AUBKC (0-24 h) (log CFU/ml/h) (mean ± SD) for TGC at concn (mg/liter): |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.025 | 0.04 | 0.17 | |

| Colistin sulfate | ||||

| 0 | 191 ± 4.4 | 189 ± 6.1 | 188 ± 7.5 | 180 ± 13.3 |

| 0.10 | 134 ± 33.6 | 164 ± 20.2 | 155 ± 24.1 | 126 ± 41.9 |

| 0.16 | 122 ± 35.6 | 150 ± 25.8 | 142 ± 28 | 128 ± 44.7 |

| 0.29 | 121 ± 41.4 | 136 ± 30.8 | 114 ± 45.5 | 107 ± 38 |

| Colistin methanesulfonate | ||||

| 0 | 191 ± 4.8 | 191 ± 6.4 | 189 ± 6.8 | 181 ± 14.3 |

| 2.1 | 111 ± 38.7 | 135 ± 40.7 | 138 ± 36.4 | 114 ± 41.2 |

| 2.7 | 115 ± 42.4 | 133 ± 34.7 | 127 ± 44 | 124 ± 49.9 |

| 8.5 | 88 ± 39.8 | 104 ± 54.3 | 101 ± 58.1 | 93 ± 39.3 |

Based on AUBKC data, combinations of peak concentrations of TGC and CS yielded an additive effect compared to CS (peak) on its own, but this was not statistically significant (P = 0.11; 95% CI, −4.5 to 33.9). However, both average (Css) and trough-level (Cmin) combinations of TGC with CS showed an antagonistic effect, and this was statistically significant (P < 0.05; 95% CI, −41.9 to −0.15 and −61.2 to −0.08, respectively). Combinations of TGC with CMS produced higher AUBKC (i.e., less killing) at all combinations, but this was not statistically significant at any of the concentrations (Table 1).

Based on the “classical” interpretive criteria for synergy or antagonism in TKC plots (i.e., the combination is >2 log more active at 24 h of incubation than the most active compound), there was no evidence of synergy between TGC and CS or CMS. Instead, there was a general trend toward antagonism, especially at lower concentrations.

The results of this study show that the addition of TGC to either CS or CMS did not produce any bactericidal benefit in terms of increasing killing at the concentrations tested, based on both AUBKC and >2-log-kill difference criteria. Instead, there was some evidence of decreased killing in the combinations at lower drug concentrations. As far as we are aware, this study is the first to look at interactions of TGC and CS/CMS against NDM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae.

These findings have potentially important therapeutic implications in the management of patients with infections caused by NDM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Tigecycline and colistin are currently the two most commonly used antibiotics in the treatment of this rapidly spreading global problem. There are compelling reasons to use them in combination: first, to prevent emergence of secondary resistance on monotherapy, especially in the treatment of complex or difficult infections; second, in the hope that combination therapy may have superior clinical activity; and finally, the recent concerns regarding the efficacy of tigecycline monotherapy.

There are a few limitations for this study. First, this work was conducted in vitro, and there are no clinical studies or case reports to support these findings. However, it is unlikely that robust clinical data on the therapies for NDM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae infection will be available for many years. Second, the rate of in vitro conversion of prodrug CMS to active colistin component is highly unpredictable. Third, we did not measure the colistin levels in the growth medium due to the lack of a validated liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS)-based colistin assay in our laboratory.

In conclusion, addition of tigecycline to colistin does not produce increased bacterial killing; instead, it may cause antagonism at lower concentrations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Sharon Tomaselli and Donna Nicholls for their assistance in carrying out laboratory experiments and T. R. Walsh for providing some of the bacterial strains.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 5 March 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Cai Y, Wang R, Liang B, Bai N, Liu Y. 2011. Effectiveness and safety of tigecycline for the treatment of infectious disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:1162–1172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dollery C. 1999. Therapeutic drugs, 2nd ed, C326 Churchill Livingstone, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dudhani RV, et al. 2010. Elucidation of the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic determinant of colistin activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in murine thigh and lung infection models. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:1117–1124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grayson LM, et al. 2010. Kucers' the use of antibiotics: a clinical review of antibacterial, antifungal and antiviral drugs, 6th ed, p 885, Table 69.2 Hodder Arnold, London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kumarasamy KK, et al. 2010. Emergence of a new antibiotic resistance mechanism in India, Pakistan, and the UK: a molecular, biological, and epidemiological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 10:597–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li J, Turnidge J, Milne R, Nation RL, Coulthard K. 2001. In vitro pharmacodynamic properties of colistin and colistin methanesulfonate against Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:781–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li J, et al. 2003. Steady-state pharmacokinetics of intravenous colistin methanesulphonate in patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:987–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. MacGowan A, Bowker K. 2002. Developments in PK/PD: optimising efficacy and prevention of resistance. A critical review of PK/PD in in vitro models. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 19:291–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Markou N, et al. 2008. Colistin serum concentrations after intravenous administration in critically ill patients with serious multidrug-resistant, gram-negative bacilli infections: a prospective, open-label, uncontrolled study. Clin. Ther. 30:143–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Poirel L, Lagrutta E, Taylor P, Pham J, Nordmann P. 2010. Emergence of metallo-β-lactamase NDM-1-producing multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli in Australia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:4914–4916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Poirel L, Revathi G, Bernabeu S, Nordmann P. 2011. Detection of NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Kenya. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:934–936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rynn C, Wootton M, Bowker KE, Alan Holt H, Reeves DS. 1999. In vitro assessment of colistin's antipseudomonal antimicrobial interactions with other antibiotics. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 5:32–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Solé M, et al. 2011. First description of an Escherichia coli strain producing NDM-1 carbapenemase in Spain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:4402–4404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yahav D, Lador A, Paul M, Leibovici L. 2011. Efficacy and safety of tigecycline: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:1963–1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]