Nonstructural protein 2 from avian infectious bronchitis virus has been overexpressed in E. coli, purified and crystallized. Diffraction data were collected to 2.8 Å resolution.

Keywords: avian infectious bronchitis virus, nonstructural protein 2

Abstract

Avian infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) is a member of the group III coronaviruses, which differ from the other groups of coronaviruses in that they do not encode the essential pathogenic factor nonstructural protein 1 (nsp1) and instead start with nsp2. IBV nsp2 is one of the first replicase proteins to be translated and processed in the viral life cycle; however, it has an entirely unknown function. In order to better understand the structural details and functional mechanism of IBV nsp2, the recombinant protein was cloned, overexpressed in Escherichia coli, purified and crystallized. The crystals diffracted to 2.8 Å resolution and belonged to space group P21, with unit-cell parameters a = 57.0, b = 192.3, c = 105.7 Å, β = 90.8°. Two molecules were found in the asymmetric unit; the Matthews coefficient was 3.9 Å3 Da−1, corresponding to a solvent content of 68.2%.

1. Introduction

Coronaviruses, which belong to the order Nidovirales, possess the largest single-stranded positive-sense RNA genomes (Bartlam et al., 2005 ▶; Zhao & Rao, 2010 ▶). Based on genetic and antigenic analyses, coronaviruses are divided into three major groups. Groups I and II contain mainly mammalian viruses, while group III contains avian viruses, including avian infectious bronchitis virus (González et al., 2003 ▶). In all coronaviruses the replicase gene covers two thirds of the genome. It consists of two large open reading frames (ORFs): ORF1a and ORF1b (Brierley et al., 1989 ▶). The two ORFs are connected by a −1 ribosomal frameshift and encode two replicase polyproteins which are processed into 15 or 16 matured nonstructural proteins to achieve viral genomic replication, assembly and maturation (Graham et al., 2008 ▶; Ma et al., 2010 ▶).

Several coronavirus replicase proteins have been characterized in the past two decades, and the three-dimensional structures that have been determined to date include those of the pathogenic factor nsp1 (Almeida et al., 2007 ▶), the papain-like protease (PL2pro, also known as nsp3; Ratia et al., 2006 ▶), the main protease (Mpro, also known as 3CLpro or nsp5; Yang et al., 2003 ▶, 2006 ▶; Zhao et al., 2008 ▶; Xia & Kang, 2011 ▶; Chen et al., 2010 ▶; Zhang et al., 2010 ▶), nsp7 in a hexadecameric supercomplex with nsp8 (Zhai et al., 2005 ▶) and with a new nsp8 isoform (Li, Zhao et al., 2010 ▶), the single-stranded RNA-binding protein nsp9 (Egloff et al., 2004 ▶), the zinc finger-containing protein nsp10 (Su et al., 2006 ▶), the uridylate-specific endoribonuclease nsp15 (Joseph et al., 2007 ▶; Xu et al., 2006 ▶) and the 2′-O-ribose methyltransferase nsp16 (Chen et al., 2011 ▶; Decroly et al., 2011 ▶).

As one of the first replicase proteins to be translated and processed, the precise mechanism of action of nsp2 is an attractive target for virological studies. Site-directed mutations in either the nsp1/nsp2 or nsp2/nsp3 cleavage sites allowed virus replication, as did mutations in the papain-like proteinase (PLP) domain of nsp3. Moreover, deletion of nsp2 in MHV and SARS-CoV resulted in viable mutant viruses, albeit with a slight attenuation of viral growth and RNA synthesis (Denison et al., 2004 ▶; Graham et al., 2005 ▶; Graham & Denison, 2006 ▶). Although it has been reported that nsp2 is not necessary for coronavirus replication and transcription, its low similarity in sequence and structure implies that it might function in host interplay. When tested by yeast two-hybrid matrix analysis, a large number of interactions between SARS-CoV nsp2 and other viral proteins were discovered in SARS-CoV (Pan et al., 2008 ▶; von Brunn et al., 2007 ▶). Furthermore, expression of MHV nsp2 from alternative locations could not complement the modest growth defects caused by nsp2 deletion, indicating that the timing and/or interactions resulting from expression between nsp1 and nsp3 might be crucial for the function of nsp2 and for optimal replication (Gadlage et al., 2008 ▶). In the work of Marne and coworkers, MHV nsp2 appeared to be more efficiently recruited to the replication–transcription complex (RTC) than other nsps and to be contained in rigid protein–protein interaction networks in the RTC (Hagemeijer et al., 2010 ▶). In addition, prohibitin 1 (PHB1) and PHB2, two proteins involved in mitochondrial biogenesis and intracellular signalling, have been identified to interact with SARS nsp2 in vitro (Cornillez-Ty et al., 2009 ▶). To gain a better understanding of the structural details and functional mechanism of coronavirus nsp2, we have determined the crystal structures of the N-terminal domain of IBV nsp2 (Yang et al., 2009 ▶) and SARS-CoV nsp2 (unpublished work). Here, we report the successful cloning, overexpression, purification and crystallization of IBV nsp2 and the preliminary characterization of selenomethionyl-derivative IBV nsp2 crystals by X-ray analysis.

2. Cloning

The gene of full-length IBV nsp2 was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from the cDNA of IBV strain M41 with an additional 6×His tag in the 3′-terminus using PrimeSTAR HS DNA polymerase (Takara). The forward PCR primer for IBV nsp2 was 5′-CG GGA TCC ATG GCT TCA AGC CTA AAA CAG GGA GTA TCT CCC AAA CTA AG-3′, containing a BamHI restriction site (bold), and the reverse PCR primer 5′-CCG CTC GAG TTA GTG GTG GTG GTG GTG GTG GCC TGC TTT GCA AAC CAC-3′ was designed with a XhoI restriction site (bold). The PCR conditions were 30 cycles of 30 s at 367 K, 30 s at 328 K and 2 min at 345 K. Digested PCR products were inserted into a BamHI/XhoI-digested pGEX-6p-1 vector (Amersham Biosciences). After transformation into Escherichia coli Top10, positive clones were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The final protein product contained five additional residues (GPLGS) at the N-terminus and a 6×His tag at the C-terminus, with a theoretical molecular mass of 76 180 Da.

3. Protein expression and purification

The recombinant plasmid was transformed into E. coli strain BL21 (DE3) for protein overexpression (Li, Zhang et al., 2010 ▶). Transformed cells were cultured at 310 K in 2×YT medium containing 100 mg l−1 ampicillin. When the OD600 reached 0.6, the culture was cooled to 289 K and supplemented with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). After induction for an additional 20 h at 289 K, the cells were harvested by centrifugation and the pellets were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer containing 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.76 mM KH2PO4 pH 7.4 and disrupted using an ultrahigh-pressure cell disrupter (JNBIO, Guangzhou, People’s Republic of China) at 277 K. The cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 20 000g for 45 min.

The fusion protein was initially purified using glutathione affinity chromatography. The target protein was treated with PreScission protease (Amersham Biosciences) for 16 h to remove the glutathione S-transferase (GST) tag at 189 K. The eluate was subsequently purified by Ni2+–NTA agarose affinity chromatography and eluted using MCAC-500 buffer (metal-chelate affinity chromatography buffer with additional 500 mM imidazole) consisting of 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 10%(v/v) glycerol, 500 mM imidazole. The target protein was further purified by gel filtration on a Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare) in a buffer consisting of 20 mM MES pH 6.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.001% NP-40.

The selenomethionyl (SeMet) derivative of IBV nsp2 was expressed in a minimal medium that inhibits methionine synthesis. The transformed BL21 (DE3) cells were incubated overnight in LB medium at 310 K and harvested at 2200g (10 min, 277 K). The pellet was transferred into 1 l M9 medium (supplemented with 100 mg l−1 ampicillin, 0.4% glucose, 100 mg each of Lys, Phe and Thr and 50 mg each of Ile, Leu, Val and SeMet) at 310 K until the OD600 reached 0.6. After addition of the seven amino-acid supplements again and induction with 0.5 mM IPTG, the cells were grown at 289 K for a further 20 h. The SeMet-labelled protein was purified using the same procedure as was used for the native protein.

4. Crystallization

Freshly prepared IBV nsp2 protein was concentrated to 20 mg ml−1 in a buffer consisting of 20 mM MES pH 6.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.001% NP-40. Initial crystallization conditions were screened at 291 K by the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method using commercially available Hampton Research crystal screening kits (Crystal Screen, Crystal Screen 2, PEG/Ion and SaltRx). Droplets consisting of 1 µl protein solution and 1 µl reservoir solution were equilibrated against 200 µl reservoir solution in 16-well plates.

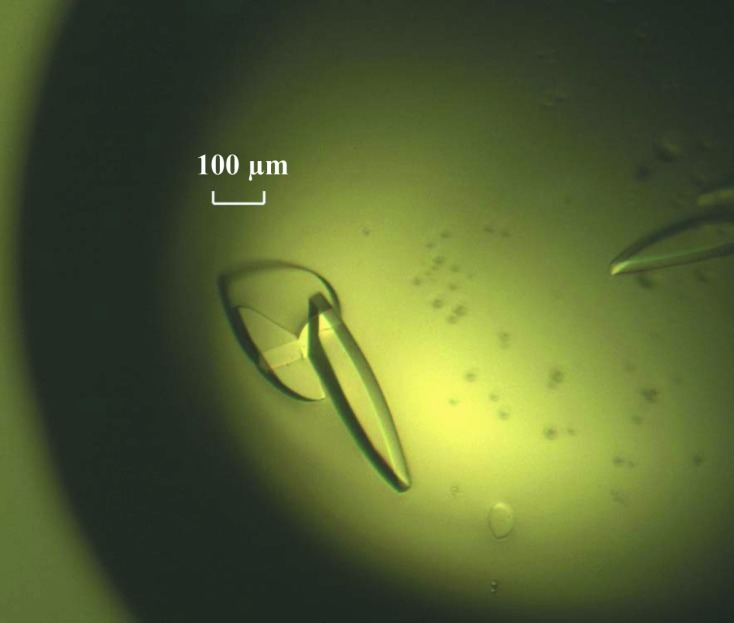

After 6 d, plate-shaped crystals of various sizes appeared under several conditions from Crystal Screen 2. All of these initial crystals showed poor diffraction. Further crystal optimization was performed by carefully adjusting the concentration of precipitant, the crystallization temperature and the buffer pH value as well as by using Additive Screen and Detergent Screen from Hampton Research. Eventually, large single crystals with good diffraction quality were found in a condition consisting of 9% PEG 4000 and 100 mM MES pH 6.5 supplemented with proline (0.2 µl) and urea (0.2 µl) at 277 K within one week (dimensions of 300 × 100 × 50 µm; Fig. 1 ▶). Native and SeMet-derivative crystals of IBV nsp2 protein grew in the same conditions. Because the crystals of IBV nsp2 were fragile in the cryoprotectant and the heavy protein precipitant in the droplet was hard to properly remove, extensive numbers of crystals were carefully selected for data collection.

Figure 1.

Single crystals of native IBV nsp2.

5. X-ray diffraction analysis

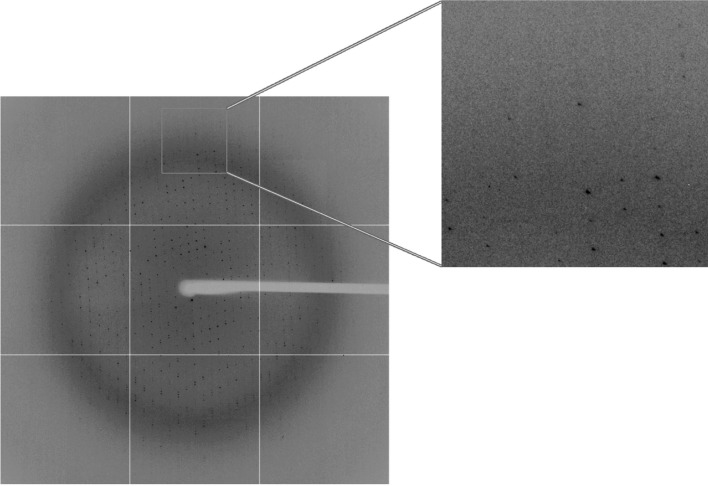

Single crystals of SeMet-labelled IBV nsp2 were transferred into reservoir solution supplemented with 20%(v/v) glycerol, dehydrated by soaking them in mother liquor supplemented with 20%(v/v) glycerol three times (each for 30 s) as previously suggested (Zuo et al., 2007 ▶) and then flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen at 100 K. All X-ray diffraction data sets were collected on beamline BL17A at the Photon Factory, Japan using an ADSC Q270 CCD detector. Because the native crystals did not diffract beyond 3.0 Å resolution, a data set was not collected from these crystals. The crystals belonged to space group P21, with unit-cell parameters a = 57.0, b = 192.3, c = 105.7 Å, β = 90.8° (Fig. 2 ▶). Assuming that there are two molecules in the asymmetric unit gives a Matthews coefficient of 3.87 Å3 Da−1 with a solvent content of 68.2% (Matthews, 1968 ▶). All data were processed with the HKL-2000 program suite (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997 ▶). The final statistics of data collection and processing are summarized in Table 1 ▶.

Figure 2.

A typical diffraction pattern of an IBV nsp2 crystal. The diffraction image was collected on beamline 17A at the Photon Factory, Tsukuba, Japan using an ADSC Q270 CCD detector.

Table 1. Data-collection and processing statistics for SeMet-derivative IBV nsp2.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Unit-cell parameters | |

| a (Å) | 57.0 |

| b (Å) | 192.3 |

| c (Å) | 105.7 |

| β (°) | 90.8 |

| Space group | P21 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9798 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.0–2.8 (2.85–2.80) |

| Total No. of reflections | 419446 (21249) |

| No. of unique reflections | 55476 (2796) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.2 (98.9) |

| Average I/σ(I) | 12.9 (6.5) |

| Rmerge† (%) | 9.5 (51.8) |

R

merge =

, where 〈I(hkl)〉 is the mean of the observations I

i(hkl) of reflection hkl.

, where 〈I(hkl)〉 is the mean of the observations I

i(hkl) of reflection hkl.

Heavy-atom searches and initial phasing were performed using SHELX (Sheldrick, 2008 ▶) and PHENIX (Adams et al., 2002 ▶). 14 heavy atoms were found by both SHELX and PHENIX with occupancies of over 70%. The selenomethionine sites were localized and interpretable maps were obtained. Density-modification procedures were performed using RESOLVE and DM (Terwilliger, 2000 ▶) in CCP4. The final figure of merit (FOM) was over 60%, suggesting that correct phasing had been obtained. Model building and refinement are under way.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Photon Factory in Japan for their assistance with data collection and technical assistance. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant Nos. 31100208 and 31000332), the Ministry of Science and Technology 973 Project and the National Major Project.

References

- Adams, P. D., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Hung, L.-W., Ioerger, T. R., McCoy, A. J., Moriarty, N. W., Read, R. J., Sacchettini, J. C., Sauter, N. K. & Terwilliger, T. C. (2002). Acta Cryst. D58, 1948–1954. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Almeida, M. S., Johnson, M. A., Herrmann, T., Geralt, M. & Wüthrich, K. (2007). J. Virol. 81, 3151–3161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bartlam, M., Yang, H. & Rao, Z. (2005). Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 15, 664–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brierley, I., Digard, P. & Inglis, S. C. (1989). Cell, 57, 537–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brunn, A. von, Teepe, C., Simpson, J. C., Pepperkok, R., Friedel, C. C., Zimmer, R., Roberts, R., Baric, R. & Haas, J. (2007). PLoS One, 2, e459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chen, S., Jonas, F., Shen, C. & Hilgenfeld, R. (2010). Protein Cell, 1, 59–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y., Su, C., Ke, M., Jin, X., Xu, L., Zhang, Z., Wu, A., Sun, Y., Yang, Z., Tien, P., Ahola, T., Liang, Y., Liu, X. & Guo, D. (2011). PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cornillez-Ty, C. T., Liao, L., Yates, J. R. III, Kuhn, P. & Buchmeier, M. J. (2009). J. Virol. 83, 10314–10318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Decroly, E., Debarnot, C., Ferron, F., Bouvet, M., Coutard, B., Imbert, I., Gluais, L., Papageorgiou, N., Sharff, A., Bricogne, G., Ortiz-Lombardia, M., Lescar, J. & Canard, B. (2011). PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Denison, M. R., Yount, B., Brockway, S. M., Graham, R. L., Sims, A. C., Lu, X. & Baric, R. S. (2004). J. Virol. 78, 5957–5965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Egloff, M.-P., Ferron, F., Campanacci, V., Longhi, S., Rancurel, C., Dutartre, H., Snijder, E. J., Gorbalenya, A. E., Cambillau, C. & Canard, B. (2004). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 101, 3792–3796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gadlage, M. J., Graham, R. L. & Denison, M. R. (2008). J. Virol. 82, 11964–11969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- González, J. M., Gomez-Puertas, P., Cavanagh, D., Gorbalenya, A. E. & Enjuanes, L. (2003). Arch. Virol. 148, 2207–2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Graham, R. L. & Denison, M. R. (2006). J. Virol. 80, 11610–11620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Graham, R. L., Sims, A. C., Brockway, S. M., Baric, R. S. & Denison, M. R. (2005). J. Virol. 79, 13399–13411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Graham, R. L., Sparks, J. S., Eckerle, L. D., Sims, A. C. & Denison, M. R. (2008). Virus Res. 133, 88–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hagemeijer, M. C., Verheije, M. H., Ulasli, M., Shaltiël, I. A., de Vries, L. A., Reggiori, F., Rottier, P. J. & de Haan, C. A. (2010). J. Virol. 84, 2134–2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Joseph, J. S., Saikatendu, K. S., Subramanian, V., Neuman, B. W., Buchmeier, M. J., Stevens, R. C. & Kuhn, P. (2007). J. Virol. 81, 6700–6708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.-J., Zhang, K., Zhai, Y.-J., Zhou, Q.-J., Geng, Y.-Q. & Sun, F. (2010). Acta Biophys. Sin. 26, 37–48.

- Li, S., Zhao, Q., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y., Bartlam, M., Li, X. & Rao, Z. (2010). Protein Cell, 1, 198–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y., Tong, X., Xu, X., Li, X., Lou, Z. & Rao, Z. (2010). Protein Cell, 1, 688–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Matthews, B. W. (1968). J. Mol. Biol. 33, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1997). Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pan, J., Peng, X., Gao, Y., Li, Z., Lu, X., Chen, Y., Ishaq, M., Liu, D., Dediego, M. L., Enjuanes, L. & Guo, D. (2008). PLoS One, 3, e3299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ratia, K., Saikatendu, K. S., Santarsiero, B. D., Barretto, N., Baker, S. C., Stevens, R. C. & Mesecar, A. D. (2006). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 103, 5717–5722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G. M. (2008). Acta Cryst. A64, 112–122. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Su, D., Lou, Z., Sun, F., Zhai, Y., Yang, H., Zhang, R., Joachimiak, A., Zhang, X. C., Bartlam, M. & Rao, Z. (2006). J. Virol. 80, 7902–7908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Terwilliger, T. C. (2000). Acta Cryst. D56, 965–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Xia, B. & Kang, X. (2011). Protein Cell, 2, 282–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Xu, X., Zhai, Y., Sun, F., Lou, Z., Su, D., Xu, Y., Zhang, R., Joachimiak, A., Zhang, X. C., Bartlam, M. & Rao, Z. (2006). J. Virol. 80, 7909–7917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yang, A., Wei, L., Zhao, W., Xu, Y. & Rao, Z. (2009). Acta Cryst. F65, 788–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yang, H., Bartlam, M. & Rao, Z. (2006). Curr. Pharm. Des. 12, 4573–4590. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yang, H., Yang, M., Ding, Y., Liu, Y., Lou, Z., Zhou, Z., Sun, L., Mo, L., Ye, S., Pang, H., Gao, G. F., Anand, K., Bartlam, M., Hilgenfeld, R. & Rao, Z. (2003). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 100, 13190–13195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Y., Sun, F., Li, X., Pang, H., Xu, X., Bartlam, M. & Rao, Z. (2005). Nature Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 980–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S., Zhong, N., Xue, F., Kang, X., Ren, X., Chen, J., Jin, C., Lou, Z. & Xia, B. (2010). Protein Cell, 1, 371–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q., Li, S., Xue, F., Zou, Y., Chen, C., Bartlam, M. & Rao, Z. (2008). J. Virol. 82, 8647–8655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q. & Rao, Z. H. (2010). Acta Biophys. Sin. 26, 14–25.

- Zuo, Y., Zheng, H., Wang, Y., Chruszcz, M., Cymborowski, M., Skarina, T., Savchenko, A., Malhotra, A. & Minor, W. (2007). Structure, 15, 417–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]