Abstract

Background

The guidelines for resection of gallbladder cancer include a regional lymphadenectomy; yet it is uncommonly performed in practice and inadequately described in the literature. The present study describes the technique of a regional lymphadenectomy for gallbladder cancer, as practiced by the author.

Methods/Technique

After confirming resectability, the duodenum is kocherized. The dissection starts from the posterior aspects of the duodenum and head of the pancreas and extends superiorly to the retroportal area. This is followed by dissection of the common hepatic artery and its branches, the bile duct and the anterior aspect of the portal vein until the hepatic hilum. Resection of the gallbladder with an appropriate liver resection completes the surgery.

Results

This technique was used for a regional lymphadenectomy in 27 patients, of which 14 underwent radical cholecystectomy upfront, and 13 had revisional surgery for incidentally detected gallbladder cancer. The median number of lymph nodes dissected on histopathology was 8 (range 3 to 18). Eleven patients had metastatic lymph nodes on histopathological examination. There was no post-operative mortality. Two patients had a bile leak which resolved with conservative management.

Conclusion

A systematic approach towards a regional lymphadenectomy ensures a consistent nodal harvest in patients undergoing radical resection for gallbladder cancer.

Keywords: radical cholecystectomy, lymphadenectomy, surgical technique, gallbladder cancer, postoperative mortality, nodal harvest

Introduction

Gallbladder cancer is a common malignancy in northern India.1 Only a small percentage of the patients have operable disease and should be treated with radical surgery. Patients who have an operable gallbladder mass or incidentally diagnosed gallbladder cancer post cholecystectomy which invades the muscularis layer or beyond 2 should be considered for radical cholecystectomy or radical revisional surgery, respectively. This surgery should include a regional lymphadenectomy.

The steps for radical surgery for gallbladder cancer can be divided into two parts: resection of gallbladder with a part of the liver, and regional lymph node dissection. While a lot of attention has been paid in the literature regarding the extent of liver resection,3 very little has been discussed in the literature or in practice about the adequacy of lymph node dissection. The aim of the present study was to describe the steps of regional lymph node dissection in gallbladder cancer as practiced by the author.

Surgical technique

Having excluded the presence of distant disease via a laparoscopy followed by a formal laparotomy, the following steps were undertaken.

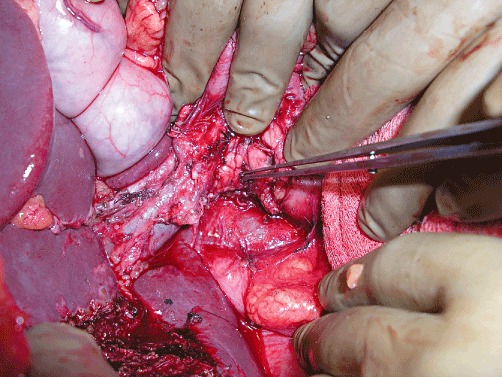

Kocherization of the duodenum and dissection of the lymph nodes behind the pancreatic head and the duodenum (Fig. 1)

Figure 1.

Dissection along the posterior surface of the pancreatic head and the duodenum. Forceps pointing to the exposed pancreatic head; the inferior vena cava can be seen behind. The dissection has proceeded cranially to expose the portal vein from behind

The duodenum is kocherized to expose the inferior vena cava and aorta. Any aortocaval node, if enlarged, is sampled. The lymph node dissection starts by removing the fibro-fatty tissue and nodes behind the head of pancreas and the duodenum and exposing the posterior surface of the pancreatic head. As the dissection proceeds cranially, the portal vein is exposed from behind. This retroportal dissection is continued as cranially as possible towards the hepatic hilum. There is no significant branch of the portal vein posteriorly and this part of the dissection is easily carried out. The superior pancreaticoduodenal vein that drains into the portal vein is usually protected by the uncinate process of the pancreas. In certain situations where this vein terminates into the portal vein at a level above the head of the pancreas, it can be easily identified and preserved. In about 20% of patients, an aberrant or accessory right hepatic artery arises from the superior mesenteric artery and courses along the portal vein. This is carefully identified and preserved if present. Occasionally, some troublesome bleeding can be encountered while removing the lymph nodes behind the pancreas; this is controlled generally by pressure or cauterization.

Exposure of the common hepatic artery (Fig. 2)

Figure 2.

Forceps pointing to the common hepatic artery. The hepatic artery branches have been dissected. The common bile duct (CBD) is also dissected. The right hepatic artery is seen until it goes behind the common bile duct. The dissection in the triangle formed by the hepatic artery, CBD and the superior surface of the pancreas exposes the anterior surface of the portal vein

The gastrohepatic ligament is divided and the hepatoduodenal ligament is encircled to prepare for the Pringle manoeuver, if necessary. The dissection starts by exposing the superior border of the pancreas and this tissue is swept superiorly. This exposes the common hepatic artery and a lymph node dissection is performed along this artery and is extended to remove the celiac nodes as well. Small branches of the artery may be encountered and are dealt with either using electrocautery or surgical clips. Extending the dissection towards the liver exposes the gastroduodenal branch which is preserved, and the right gastric artery which is divided to facilitate easy retrieval of the lymph nodes in this region. Division of the right gastric artery also aids the exposure and dissection of the anterior surface of the portal vein that is done as a later step.

Dissection along the hepatic artery branches (Fig. 2)

The common hepatic artery is skeletonized and traced towards the liver. In the process, the tissue along the right and left hepatic artery is removed and these branches are skeletonized. The right hepatic artery would generally course posterior to the bile duct and further dissection along this is reserved for the next step. Often, a branch to segment 4 is seen separately; this is dissected and preserved. The left border of the portal vein is also exposed while dissecting the hepatic artery branches. The dissection is continued into the hepatic hilum.

Skeletonization of the common bile duct (Figs 2,3)

Figure 3.

CBD has been retracted anteriorly to dissect the right hepatic artery behind it until the hepatic hilum. Retroportal dissection is also completed

The pericholedochal tissue and nodes are dissected from below upwards so that the bile duct is exposed. If the gallbladder is intact, the cystic artery is divided flush with the right hepatic artery, and the cystic duct is identified and divided flush with the common bile duct. If a revisional surgery is being performed, the cystic duct stump is identified and resected at its junction with the common bile duct. The dissection proceeds cranially until the hepatic hilum; in the process, bifurcation of the right and left hepatic ducts is often exposed. The right hepatic artery is now dissected from behind the bile duct and this dissection proceeds until the hepatic hilum (Fig. 3). If the cystic duct margin is involved grossly or by frozen section, the bile duct is resected and a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy performed at the end of the surgery.

Dissection of the anterior surface of the portal vein (Fig. 2)

Attention is now paid to the triangle formed by the superior border of pancreas below, common bile duct on the right, and hepatic artery–gastroduodenal artery on the left with the artery and duct meeting superiorly at the apex of the triangle. The fibro-fatty tissue and lymph nodes in this triangle are dissected; this exposes the anterior surface of the portal vein. The bile duct is gently retracted to the left and the tissue along the anterior surface of the portal vein is dissected to skeletonize the portal vein until the hepatic hilum. This completes the regional lymphadenectomy for gallbladder cancer.

This is followed by removal of the gallbladder and an appropriate liver resection, tailored to the degree of liver invasion.

Results

Between May 2007 and March 2011, the author has performed radical surgery for gallbladder cancer in 27 patients. There were 18 women and 9 men, with a median age of 52 years (range 32 to 70). A radical cholecystectomy was performed in 14 and revision surgery was performed in 13 patients. A regional lymphadenectomy was performed using the described technique in all of these patients. A wedge resection of the liver was performed in 15 patients, anatomic segment 4b/5 resection in 11 and an extended right hepatectomy in 1 patient. Three patients had a bile duct resection followed by a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy.

There was no post-operative mortality. Two patients developed post-operative bile leak: one had wedge resection of the liver and the other had an extended right hepatectomy with bile duct resection. Both resolved with conservative management. No patient developed a pancreatic fistula.

The median number of lymph nodes dissected on histopathological examination was 8 (range 3 to 18). Two patients who had less than six nodes dissected had both received chemotherapy (6 cycles of cisplatin and 5 fluorouracil, 4 cycles of gemcitabine and oxaliplatin) before undergoing a radical cholecystectomy. Eleven patients had positive nodes on histopathological examination, with a median of 2 positive nodes per patient (range 1 to 5 positive nodes per patient).

Discussion

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend hepatic resection and a lymphadenectomy for gallbladder cancer.4 A regional lymphadenectomy is a neglected part of the surgical procedure performed for gallbladder cancer. In an analysis of 2955 patients with gallbladder cancer who underwent cancer-directed surgery in the United States of America between 1991 and 2005, only 96 patients (3%) had 3 or more lymph nodes dissected to qualify for an adequate lymphadenectomy. Significantly, among the patients who underwent a lymphadenectomy, 47% had nodal metastasis. In that study, liver resection and a lymphadenectomy (3 or more nodes) were independent predictors of survival on multivariate analysis.5 In another study on 4614 patients with gallbladder cancer from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry, the authors observed that a radical resection alone (without lymph node evaluation) did not provide any benefit over a cholecystectomy alone.6

As per the American Joint Committee on Cancer suggestion, several authors have considered dissection of at least three lymph nodes to qualify as a lymphadenectomy.5 In an analysis of lymph node excision data from the SEER database on gallbladder cancer, it was shown that patients with one to four nodes excised had a survival benefit over those with no lymph node excised, and patients with five or more nodes excised had a survival advantage over patients with one to four nodes excised.7 Only 28.2% of patients had 1 to 4 nodes excised, and 3.6% had 5 or more lymph nodes excised in this analysis. A single institution study from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center involving 122 patients undergoing radical surgery for gallbladder cancer showed that survival of patients classified as N0 based on a total lymph node count (TLNC) less than 6 was significantly worse than that of N0 patients based on TLNC of 6 or more. Although the median TLNC in that study was 3 (range 0 to 20), the authors concluded that resection and histological evaluation of at least 6 lymph nodes improves risk stratification after surgery for gallbladder cancer.8 In contrast, the median lymph node dissected in the present study was 8 (range 3 to 18). Only two out of 27 patients had less than 6 nodes dissected; both received chemotherapy before a radical cholecystectomy.

There has been some debate about the extent of lymph node dissection required for gallbladder cancer. Many consider dissection of the cystic, pericholedochal and hepatoduodenal nodes to be sufficient. However, the study of recurrence patterns after curative surgery indicates that the lymphadenectomy should also include retroportal, posterior pancreatoduodenal, common hepatic and right celiac nodes.9 Some authors would include the aortocaval nodes; however, most consider the aortocaval nodal metastasis as a distant spread.10

In conclusion, a regional lymphadenectomy is an integral part of surgery for gallbladder cancer. With careful attention to the technique, an adequate number of nodes to allow accurate staging can be retrieved with minimal morbidity.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Nandakumar A, Gupta PC, Gangadharan P, Visweswara RN, Parkin DM. Geographic pathology revisited: development of an atlas of cancer in India. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:740–754. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abramson MA, Pandharipande P, Ruan D, Gold JS, Whang EE. Radical resection for T1b gallbladder cancer: a decision analysis. HPB (Oxford) 2009;11:656–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2009.00108.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dixon E, Vollmer CM, Jr, Sahajpal A, Cattral M, Grant D, Doig C, et al. An aggressive surgical approach leads to improved survival in patients with gallbladder cancer: a 12 year study at a North American center. Ann Surg. 2005;241:385–394. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000154118.07704.ef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN guidelines) 2011. Practical guidelines in oncology. Hepatobiliary cancers. Version 1. Available at: http://www.nccn.org.

- 5.Mayo SC, Shore AD, Nathan H, Edil B, Wolfgang CL, Hirose K, et al. National trends in the management and survival of surgically managed gallbladder adenocarcinoma over 15 years: a population-based analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1578–1591. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jensen EH, Abraham A, Jarosek S, Habermann EB, Al-Refaie WB, Vickers SA, et al. Lymph node evaluation is associated with improved survival after surgery for early stage gallbladder cancer. Surgery. 2009;146:706–713. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Downing SR, Cadogan KA, Ortega G, Oyetubji TA, Siram SM, Chang DC, et al. Early-stage gallbladder cancer in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Result database: effect of extended surgical resection. Arch Surg. 2011;146:734–738. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ito H, Ito K, D'Angelica M, Gonen M, Klimstra D, Allen P, et al. Accurate staging for gallbladder cancer: implications for surgical therapy and pathological assessment. Ann Surg. 2011;254:320–325. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822238d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noie T, Kubota K, Abe H, Kimura W, Harihara Y, Takayama T, et al. Proposal on the extent of lymph node dissection for gallbladder carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:2122–2127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reid KM, Ramos-De la Medina A, Donohue JH. Diagnosis and surgical management of gallbladder cancer: a review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:671–681. doi: 10.1007/s11605-006-0075-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]