Abstract

At this time, compared with mainstream (Caucasian) youth, cultural minority adolescents experience more severe substance-related consequences and are less likely to receive treatment. While several empirically supported interventions (ESIs), such as motivational interviewing (MI), have been evaluated with mainstream adolescents, fewer published studies have investigated the fit and efficacy of these interventions with cultural minority adolescents. Additionally, many empirical evaluations of ESIs have not explicitly attended to issues of culture, race, and socioeconomic background in their analyses. As a result, there is some question about the external validity of ESIs, particularly in disadvantaged cultural minority populations. This review seeks to take a step towards filling this gap, by addressing how to improve the fit and efficacy of ESIs like MI with cultural minority youth. Specifically, this review presents the existing literature on MI with cultural minority groups (adult and adolescent), proposes two approaches for evaluating and adapting this (or other) behavioral interventions, and elucidates the rationale, strengths, and potential liabilities of each tailoring approach.

Keywords: substance abuse, treatment, cultural minority, adolescents

1. Introduction

1.1 Health disparities

Similar to the current composition of some states (e.g., New Mexico), the United States is quickly on its way to becoming a minority majority country, where racial/ethnic (cultural) minority groups will be predominant, and current “mainstream” groups (e.g., Caucasian) will be less prominent. During the next 15 years, it is projected that there will be great gains in the population by Asian Americans, Hispanic Americans, African Americans, and American Indian/Alaska Natives (AIAN) (Campbell, 1996). And, it is estimated that each of these cultures will comprise a significant proportion of the nation. For example, the percentage of Hispanic Americans alone is estimated to rise from 16.3% to 25% of the total population (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, & Lee, 2006).

Despite the major presence of cultural minority groups within the U.S., significant health disparities still exist (Carter-Pokras & Baquet, 2002), particularly in the treatment of addiction (Lowman & Le Fauve, 2003; Russo, Purohit, Foudin, & Salin, 2004). To this end, the manifestation and treatment of addiction is not equitable across cultural groups. Rather, studies have found that cultural minorities bear a substantially greater burden of substance-related consequences (Caetano, 2003; Galea & Vlahov, 2002; Nina Mulia, Ye, Greenfield, & Zemore, 2009; Mulia, Ye, Zemore, & Greenfield, 2008). Among adults, this has taken the form of greater levels of substance-related morbidity and mortality, including cancer, cirrhosis, arrests for driving under the influence (DUI), and intimate partner violence (Trujillo, Castañeda, Martínez, & Gonzalez, 2006). And, among adolescents, studies have indicated that despite equivalent (if not lower) rates of substance use among cultural minority youth (Feldstein Ewing, Venner, Mead, & Bryan, 2011), cultural minority adolescents evidence substantially greater levels of substance-related problems, including drinking and driving, riding with a drinking driver, experiencing violence (physical fighting and relationship violence), and sexual risk behavior (CDC, 2010; Hellerstedt, Peterson-Hickey, Rhodes, & Garwick, 2006; S. Walker, Treno, Grube, & Light, 2003).

Several factors may contribute to these differences in substance use and related consequences. For example, differences in patterns of consumption might lead to some of the observed differences in consequences (e.g., Arroyo, Miller, & Tonigan, 2003). Additionally, among cultural minority adolescents, greater rates of poverty, higher visibility of and exposure to substances, perceived ease of obtaining substances, and higher levels of community policing in the youths’ community may also play a role (Wallace, 1999). Furthermore, there may also be a differential pattern of treatment and referral between cultural minority and mainstream Caucasian youth, whereby cultural minority youth may be “referred” to justice settings, rather than being referred to treatment (e.g., Aarons, Brown, Garland, & Hough, 2004; Feldstein, Venner, & May, 2006). Moreover, at this time, cultural minority adolescents are less likely than Caucasian youth to receive substance abuse interventions (e.g., Garland et al., 2005; Wallace, 1999; P. Wu, Hoven, Tiet, Kovalenko, & Wicks, 2002), and evidence lower levels of treatment engagement and completion (Alegria, Carson, Goncalves, & Keefe, 2011). Most critically, most examinations of adolescent substance abuse treatment efficacy and related factors have been limited to mainstream, Caucasian youth; at this time, there is great need to improve our understanding of treatment with cultural minority youth in order to improve intervention efficacy (Austin, Hospital, Wagner, & Morris, 2010).

1.2 The promise of motivational interviewing (MI)

As cultural minority youth may be less likely to successfully engage in, receive, or complete substance abuse interventions, innovative approaches are needed to reach these high-need and underserved youth. One approach that has demonstrated promise is motivational interviewing (MI; W. R. Miller & Rollnick, 2002). The brevity and transportability of this intervention has made it ideal for articulation to settings where hard-to-reach youth may emerge, such as juvenile justice settings, medical settings, and schools (e.g., D’Amico, Miles, Stern, & Meredith, 2008; Feldstein & Ginsburg, 2006; Martin & Copeland, 2008; McCambridge, Slym, & Strang, 2008; Peterson, Baer, Wells, Ginzler, & Garrett, 2006; Spirito et al., 2004; Stein et al., 2011; D. D. Walker, Roffman, Stephens, Wakana, & Berghuis, 2006). Not only is this brief (1-2 session), empathic, and strength-based intervention highly transportable, it also highly effective across a number of substance use and health risk behaviors (e.g., Hettema, Steele, & Miller, 2005; Lundahl, Kunz, Brownell, Tollefson, & Burke, 2010). Moreover, it is particularly good at facilitating therapeutic alliance with wary recipients, such as non-treatment-seeking, substance abusing youth (D’Amico et al., 2008; McCambridge et al., 2008; Peterson et al., 2006). Additionally, qualitative studies have suggested that the approach of MI resonates with this age group, with high percentages of youth reporting that they liked the MI interventions and would recommend it to a friend (D’Amico, Osilla, & Hunter, 2010; Martin & Copeland, 2008; Stern, Meredith, Gholson, Gore, & D’Amico, 2007). This is likely due to the non-judgmental, empathic, and collaborative approach of MI (e.g., W. R. Miller, Villanueva, Tonigan, & Cuzmar, 2007), whereby adolescents’ own values, opinions, and arguments for change are the most valued and reflected part of the therapeutic discussion.

While MI holds promise for use with cultural minority youth, few studies have explicitly evaluated the “fit” of MI across cultural groups. This is concerning, as there are also many aspects of MI that may work less well for cultural minority youth. For example, in contrast to the egalitarian approach of MI, where the therapist is expected to be “on the same level” as their clients, some cultural groups may wish to receive help from someone who is an expert (e.g., Lopez Viets, 2007) and may be more comfortable with, and/or even desire client-therapist power differentials (e.g., Hays, 2009; S. T. Miller, Marolen, & Beech, 2010). Furthermore, some cultural groups may prefer for other family members (parents, grandparents) to be actively involved in therapy, rather than having their child attend an adolescent-only individual-level or group-level intervention (e.g., Lopez Viets, 2007).

Even though the potential fit of MI with cultural minority youth has not been fully examined, MI has been widely-disseminated across settings where cultural minority youth predominate, and further, has been actively promoted as an intervention for use with cultural minority youth (Kirk, Scott, & Daniels, 2005). As there are aspects of MI that appear to be a good fit with cultural minority youth, but also aspects that make it potentially less efficacious, it is critical to specifically determine how to evaluate (and improve) the efficacy of interventions like MI with cultural minority youth. This review seeks to take a step towards filling this gap, by addressing how to improve the fit and efficacy of empirically supported interventions (ESIs) like MI with cultural minority youth. Specifically, this review seeks to present the existing literature on MI with cultural minority groups (adult and adolescent), propose two approaches for evaluating and adapting this (or other) behavioral intervention approaches, and elucidate the rationale, strengths, and potential liabilities of each approach.

2. Motivational interviewing (MI) with cultural minority groups

2.1 Findings with adults

Studies have indicated the impact and efficacy of brief interventions in reducing substance abuse (W. R. Miller & Wilbourne, 2002). One of the most popular and widely-disseminated brief interventions is MI. Across large scale meta-analyses with predominantly adult samples, MI has evidenced a greater effect size across cultural minority groups as compared with Caucasian populations (d = 0.79 vs. 0.26, respectively; Hettema et al., 2005). Moreover, those who have incorporated MI or related aspects into health behavior prevention/intervention efforts with predominantly cultural minority samples have found generally promising outcomes, with a handful of exceptions. Specifically, in the adult AIAN community, MI has been found to help reduce drinking behavior (d = 0.43; May et al., 2008), and related health risk behavior (d = 0.81; Foley et al., 2005). And, when directly compared with other treatments, MI has resulted in better outcomes among AIAN adults (d = 0.34 - 0.76; Villanueva, Tonigan, & Miller, 2007; Woodall, Delaney, Kunitz, Westerberg, & Zhao, 2007). Similarly, among the adult Asian American community, MI-based interventions have resulted in greater substance use reductions (tobacco quit rates 67% for MI versus 32% for control; D. Wu et al., 2009). And, among Hispanic American adults, MI-based interventions have facilitated substance use reductions (OR = 0.55, 95% CI = 0.18 - 0.91; Robles et al., 2004), as well as improvements in related health behavior (d = 0.25; Patterson et al., 2008).

Despite these positive outcomes, there have also been areas where MI has been less effective. Among African American adults, while MI has successfully catalyzed improvements in health behavior across some investigations [(e.g., 59% for MI versus 43% for controls for medication adherence; Holstad, DiIorio, Kelly, Resnicow, & Sharma, 2010); (d = 2.7 for improvements in fruit and vegetable intake; Resnicow et al., 2005)], others have not found positive outcomes with MI (e.g., Ahluwalia et al., 2006). Moreover, in a qualitative study using focus-group methodology, MI was evaluated as a potential counseling strategy to be used within a physical activity promotion program. Following their viewing of an example physician-patient consult (from a MI training DVD), rural African American women with type II diabetes reported that MI represented a good communication approach, but was too patient-centered for their comfort (S. T. Miller et al., 2010). Subsequently, the authors underscored the importance of attending to cultural group needs, and tailoring MI accordingly (e.g. to rural clinical settings and patient communication preferences).

In sum, while there is indication that MI has great potential for use with cultural minority adults across a range of substance use and related health risk behavior, the results are equivocal. It is likely that the observed differences in outcomes are influenced by the diversity that exists both within and across cultural minority groups (W. R. Miller et al., 2007). Thus, these data highlight the importance of examining the fit of this intervention to specific cultural minority groups to improve its efficacy.

2.2 Findings with youth

While fewer studies have explicitly explored the fit of MI with cultural minority youth (e.g., Gil, Wagner, & Tubman, 2004; Gilder et al., 2011), several well-conducted studies have found promising outcomes with predominantly cultural minority youth across a number of substance use and related health behaviors (e.g., D’Amico et al., 2008; Gil et al., 2004; Schmiege, Broaddus, Levin, & Bryan, 2009; Walton et al., 2010). For example, with a predominantly Hispanic adolescent sample, D’Amico and colleagues (2008) found that an MI intervention led to reductions in binge drinking episodes (d = .22), frequency of alcohol use (d = .80), frequency of marijuana use (d = .84), and affiliation with substance using peers (d’s = .37 and .66, for alcohol-using and marijuana-using, respectively). Similarly, following a motivationally-based intervention, Gil and colleagues’ (2004) sample of predominantly high-risk, African American and Hispanic youth (juvenile offenders), decreased their frequency of marijuana use from 83 - 90% to 40 - 49% of days per month, and their frequency of alcohol use from 2/3rds to 1/3rd of days per month. Additionally, with a sizeable sample of Hispanic and African American youth, Schmiege and colleagues (2009) demonstrated that adding an MI component targeting alcohol use to a sexual risk prevention program reduced the likelihood of having sex while drinking (d =.13, d = .40 when compared with sex risk without alcohol and information control conditions, respectively). In Walton and colleagues’ evaluation of MI with a substantial sample of urban African American youth (2010), the authors found 32.2% reductions in alcohol-related consequences at the 6-month follow up (OR = 0.56). And, in a qualitative assessment with AIAN youth, Gilder and colleagues (2011) found that both tribal youth and their elders believed that an MI-based intervention incorporating family members, would be acceptable within the community as an approach to reduce underage alcohol use. Similarly, in a preliminary analysis of an ongoing research protocol evaluating MI across a sample of Hispanic American and Caucasian youth (Feldstein Ewing, 2011), Hispanic American youth who received an MI intervention targeting reducing substance use, reported liking the MI intervention (n = 68; M = 4.5 on a scale of 1-5) and stated that they would recommend it to a friend (M = 4.46 on a scale of 1-5). In terms of other adolescent health behaviors, with predominantly African American samples, MI-based interventions have improved depression and readiness to change, but not self-efficacy, among HIV positive youth (Naar-King, Parsons, Murphy, Kolmodin, & Harris, 2010) as well as treatment compliance with an asthma-medication regimen (Riekert, Borrelli, Bilderback, & Rand, 2011).

While several studies have demonstrated MI’s potential with cultural minority youth, few have explicitly evaluated the role of race, ethnicity, or culture in outcomes. This area deserves attention, as preliminary evidence suggests that cultural factors may influence treatment response in MI-based interventions (e.g., level of ethnic mistrust, cultural orientation, ethnic pride; Gil et al., 2004). More research is necessary to highlight factors that may differentially influence outcomes by cultural group, in order to identify culturally-relevant variables that may be important to include in the adaptation of this intervention.

Furthermore, the wide range of effect sizes observed among the adolescent studies is reflective of the broader youth MI literature, whereby lower effects sizes have been observed across youth as compared with adult studies (ES for MI among adults = .25 vs. ES for MI among adolescents = .16; Burke et al., 2003; Jensen et al., 2011). These findings indicate that there are several areas where both the developmental, as well as the cultural fit of MI could be improved. However, few published studies have provided guidance as to how to effectively tailor empirically supported interventions (ESIs) like MI (e.g., Interian, Martinez, Rios, Krejci, & Guarnaccia, 2010), particularly with this age group. Thus to address this area of need, we provide two compelling approaches for evaluating the cultural fit of MI among adolescents, and adapting it accordingly.

3. Improving the Fit of Motivational Interviewing with Cultural Minority Youth: Adapt and Evaluate vs. Evaluate and Adapt

3.1 Adapt and Evaluate

Studies have increasingly addressed the importance of tailoring empirically supported interventions (ESIs) to cultural minority groups, particularly in adolescent treatment (e.g., Bernal, 2006; Bernal & Sharron-del-Rio, 2001; Domenech-Rodriguez, Baumann, & Schwartz, 2011; Lau, 2006). Along these lines, these researchers have suggested that ESIs offer great potential, but need refinement before implementation with different cultural minority groups (e.g., Huey & Polo, 2008; Marlatt et al., 2003; W. R. Miller et al., 2007; Venner, Feldstein, & Tafoya, 2007). One way to improve the fit of ESIs is to adapt the intervention to ensure that it has greater cultural congruence prior to administration (e.g., Bernal, 2006; Domenech-Rodriguez et al., 2011). In this approach, the goal is to retain the active ingredients of the intervention. In the example of MI, that might include aspects such as reflective listening, accurate empathy, development of discrepancy, and support of self-efficacy while delivering the intervention in a culturally congruent way (e.g., in a way that is consistent with the language, customs, attitudes, behavior, and cultural context; Interian et al., 2010). Consonant with recent efforts to involve community members in steps towards improving health equity, this approach is grounded in the community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach (Castro, Barrera, & Martinez, 2004); subsequently, community-based participation is central to this strategy. Incorporating CBPRs with adolescents has been an area gaining increasing attention (e.g., Corbie-Smith et al., 2010; Cross et al., 2011; Shetgiri et al., 2009), and provides an important way to inform and guide tailored treatment development.

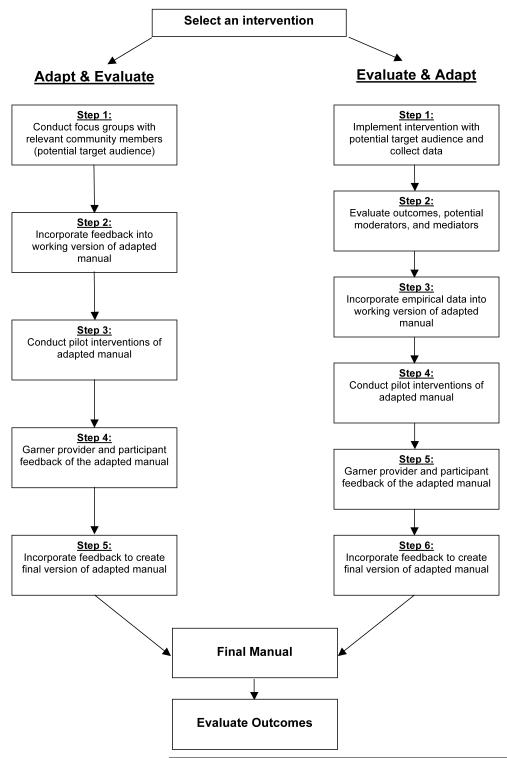

Proposed strategies for Adapt and Evaluate

Following critical work in this field (e.g., Interian et al., 2010), this proposed approach is comprised of five steps (see Figure 1). Step 1 requires organizing one to two focus groups with community members who represent the targeted cultural community of adolescents (e.g., high-risk, Hispanic American youth ages 14-18). Once the focus group has been gathered, we recommend presenting the key clinical approaches, as well as an active example of the intervention (a brief demonstration of an MI session) to determine the groups’ perspectives on the cultural congruence and acceptability of the key clinical strategies and to elucidate areas that require modification. For example, to adapt MI with Hispanic American youth, we would recommend creating two independent focus groups (e.g., four to six members in each group, with girls in one group, and boys in a second), which would be conducted by two senior staff members. Within the focus group, example stem questions might include: “How would you feel about meeting with a counselor about your substance use with your parents? Without your parents? How might your parents feel about you talking to a counselor? What about talking to a counselor without them present?” “How comfortable might you feel talking with a counselor about your thoughts and feelings, with you doing most of the talking?” “Let’s have you watch an example conversation between a counselor and a person struggling with changing their marijuana use.” “Now that you’ve seen that conversation, tell me - what things did the counselor do that you liked? What did the counselor do that you liked less? What aspects about the conversation made you more comfortable? Less comfortable?”

Figure 1.

Flow chart for two approaches to tailoring interventions

In addition to having someone take notes during the focus group (a research staff member can be positioned back behind the focus group to observe and track the proceedings), we strongly recommend audio-recording these focus groups (contingent upon the requisite community-based and institutional review board permissions) and transcribing the proceedings. While ensuring that all voices are heard is a challenge of focus-group based work (Venner et al., 2007), these procedures offer some steps towards guarding against the quieter voices being lost. Most importantly, these qualitative data are crucial for shaping adaptations to the intervention manual. Step 2 includes incorporating the feedback (generated from the focus groups) into the working version of the adapted intervention manual. In this step, if youth talked about the importance of including parents, then one would include parents in some way as part of the adapted intervention. For example, parents might be included in the orientation/welcoming session, with the second session being youth only. Or, if youth determined that parents are central to their improvement, then one would take steps towards making the MI a more family-based intervention (e.g., Dishion, Nelson, & Kavanagh, 2003; Spirito et al., 2011).

As demonstrated in Venner and colleagues (2007) recent adaptation of MI with AIAN adults, the community-based focus groups identified several facets of MI that were discrepant from AIAN cultures (e.g., absence of spirituality from the approach; the reluctance of participants to give dissenting opinions to treatment providers, as they are people in power). Thus, in Venner and colleagues’ adapted version of their MI manual, they took several steps to address these concerns. For example, they openly included spirituality in the manual (incorporating an MI-based prayer) as well as suggestions for how to actively use spirituality in a session (e.g., opening a session with a prayer), and recommendations for what to avoid (e.g., not asking participants details about their spiritual practices, as they may be sacrosanct). To attend to the issue of participants feeling like they might not be able to openly disagree with providers, the authors incorporated text describing how participants might not feel comfortable providing dissenting opinions (e.g., instead showing their disagreement by not providing behavior change during the follow-up session, or by not showing up for a second session) as well as provided a concrete example of how to conduct the “ask provide ask” tool in a less direct tone.

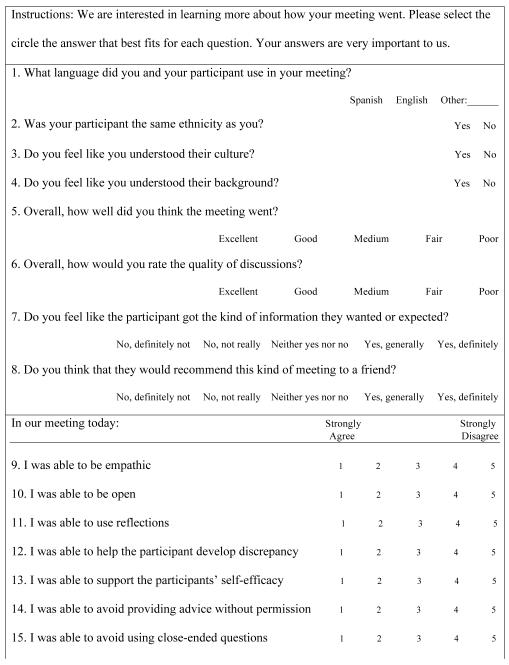

For Step 3, we recommend piloting the adapted intervention with at least five adolescent participants (for individual interventions) and with at least two adolescent groups (for group interventions) who represent the range of the targeted audience (e.g., younger youth as well as older youth, both genders). In Step 4, we recommend gathering the requisite data from the pilot testing in several ways. First, we recommend that the counselor take detailed notes about what went well and not so well regarding the intervention (stems might include “What went well in our meeting today”, “What went less well in our meeting today”, “What might have improved today’s meeting”), as well as complete an assessment of their experiences (see example provided on Table 1), and an assessment of working alliance (such as the Working Alliance Inventory; Horvath & Greenberg, 1989). Gathering these data are necessary, particularly for youth of cultures where there is a high reverence to adults and professionals, and/or for youth who are from cultures where candor is less accepted.

Table 1. Counselor Measure: Assessment of the Intervention (Subjective Report).

|

|

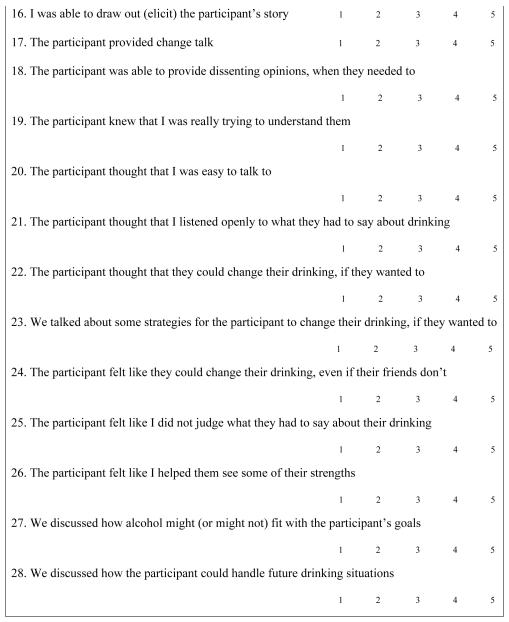

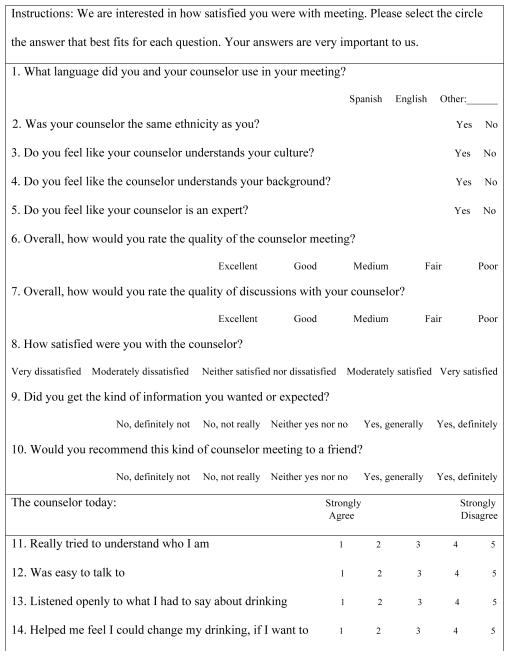

Second, even if youth are less comfortable sharing their opinion, it is important to explicitly check in with the adolescent pilot participants following the administration of the adapted intervention to see how well they liked the intervention and what they would change. In addition to completing a satisfaction measure (see Table 2 for an example), we recommend having a staff member (not the counselor), ask youth, “What things did you like about the meeting that you had with Dr. Hilary?” “What things did you like less well about the meeting with Dr. Hilary?” “What things would you change about your meeting with Dr. Hilary?” “What things do you wish that she had done differently?” While it is ideal for youth to express their opinion, it is also okay if youth only feel comfortable providing limited or fairly topical answers. Step 5 involves incorporating the diligently recorded counselor and participant feedback into the intervention manual; the resulting product is the final manual.

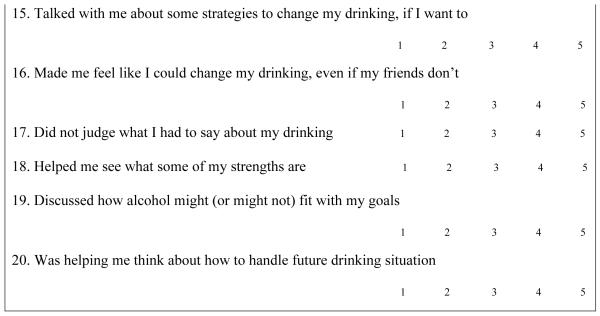

Table 2. Client Satisfaction Measure: Comfort with Intervention (Subjective Report).

|

|

3.2 Evaluate and Adapt

While the efficacy of empirically supported interventions (ESIs) among minority populations has yet to be closely scrutinized (Miranda, Nakamura, & Bernal, 2003), the findings of Hettema, Steele, and Miller (2005) suggest that it is equally possible that MI in its original form may work well (if not better) with cultural minority populations, and the aspects of MI that make it ideal for adolescent work may mean that it is an excellent fit for cultural minority youth. Notably, one compelling consideration is that while MI in its original form might be equally efficacious across cultural groups, the mechanisms of change may be different. For example, the focus on individual-oriented internal cognitions (like motivation for change) may be salient for one cultural group, while community-oriented cognitions (such as the ability to navigate peer influences) may be more salient to another group. Thus, the goal in Evaluate and Adapt is to implement the intervention in its original form, and evaluate the intervention across a number of key constructs (behavior outcome data, potential moderators and mediators) to determine how they fit for a specific cultural group. In contrast to Adapt and Evaluate which relies upon the qualitative feedback of the CBPR, this approach is grounded upon quantitative data; differential (or highly variable) behavior outcomes between or within cultural groups indicate the need to adapt the treatment to improve its efficacy (Lau, 2006), as well as provide guidelines about what facets need to be reinforced or reduced in the adaptation process.

In terms of potential factors to evaluate, we believe that it is most important to evaluate target behavior outcomes, such as quantity and frequency of substance use, and substance related problems, to determine if they differ by cultural group. Additionally, we think it is worthwhile to also evaluate moderators and mediators that might modulate adolescents’ treatment response. For example, we suggest collecting data on both therapists’ experiences with the youth (e.g., Table 1 and a working alliance measure), as well as adolescents’ subjective response to the intervention (e.g., Table 2). Evaluation of whether subjective response (acceptability) differs by cultural group is highly informative. While individual difference factors have not been found to systematically modulate therapeutic outcomes (e.g., Longabaugh et al., 2005; ProjectMatchResearchGroup, 1997), a number of constructs continue to appear salient to MI interventions (e.g., self-efficacy; LaChance, Feldstein Ewing, Bryan, & Hutchison, 2009), and some of these factors (e.g., self-efficacy) appear to differ by culture (e.g., Bryan, Robbins, Ruiz, & O’Neill, 2006; Bryan, Ruiz, & O’Neill, 2003). Thus, investigating how posited active ingredients influence adolescent outcomes and how those patterns of influence compare by culture is important. As emphasized in prior research (Gil et al., 2004; Munoz & Mendelson, 2005), it is also critical to look at cultural-level factors, such as acculturation, ethnic orientation, ethnic pride, discrimination, and religion/spirituality, as well as broader environmental factors (e.g., exposure to trauma, poverty, availability of substances in the community) to determine how these factors may influence youths’ response to the intervention. And, finally, it is important to evaluate how interested and invested cultural groups or subpopulations might be in having empirically-supported interventions. Specifically, some cultural groups of youth and their parents may resist western ESIs due to a fear that the treatment will eradicate methods of traditional and indigenous healing, or because they prefere to use familial or culturally-informed treatment strategies (e.g., Gone, 2009; Koinis-Mitchell et al., 2008). Evaluation of these factors is critical to determine how best to approach adaptation and the necessary factors that might facilitate (or hinder) implementation. This might include evaluating factors such as the need for alliance development with youth, their parents, the community before broaching intervention implementation, or determining whether the adolescent cultural group might prefer a dual-treatment strategy, where indigenous forms of healing would be deliberately integrated with empirically-supported psychosocial interventions (Hwang, 2006).

Proposed strategies for Evaluate and Adapt

The first step of this proposed approach requires implementing the original intervention (e.g., MI) with an identified group of adolescent participants (e.g., with African American and Caucasian youth; See Figure 1). To gather the requisite data to guide the adaptation, it is imperative to measure both basic behavior outcome data (e.g., quantity and frequency of use, substance-related problems) as well as the key constructs of interest (e.g., therapists’ perception of the intervention, adolescents’ perception of the intervention, individual difference factors, cultural factors, environmental factors).

Once the intervention has been implemented and behavior outcome data have been collected (Step 1), Step 2 requires evaluating the outcomes, the potential moderators, and the potential mediators. Through this step, one might find that MI is less effective with one of the adolescent cultural subgroups (e.g., Befort et al., 2008; S. T. Miller et al., 2010), or that different factors appear to influence behavior outcomes more for one cultural group or another, or even within different cultural groups themselves (e.g., Nagayama Hall, 2001; Tubman, Gil, & Wagner, 2004). Similar to how the qualitative research data were integrated into the revised manual in Adapt and Evaluate, in Step 3 of Evaluate and Adapt, these quantitative data are used to guide the modification of MI to make it more efficacious for the target community of adolescents. Specifically, if self-efficacy appeared to have a greater impact for African American youth, then more MI-consistent exercises designed to foster and support self-efficacy could be included in the adapted manual (e.g., youth version of adjectives of successful changers; success stories; Feldstein & Ginsburg, 2007; Moyers, 2005). Once all of the requisite adaptations have been made to the manual, as with Adapt and Evaluate, we recommend taking the following three steps to ensure that the adapted manual is tenable, feasible, and acceptable to participants, again incorporating any suggestions that they provide into the final manual. Specifically, Steps 4 through 6 include pilot testing the adapted manual with at least 5 adolescent participants (for individual interventions) and at least 2 adolescent groups (for group interventions), using qualitative and quantitative approaches to explicitly check in with the interventionists and pilot participants to determine how acceptable the intervention was (e.g., how well they liked the intervention and if and what they might change), and incorporating their feedback into the final manual.

3.3 How do we know its MI?

Perhaps the most important question across both approaches is whether the intervention has retained its key active ingredients. While adaptations to various MI interventions have been made across cultural subgroups, considerably less attention has been paid to evaluating outcomes of the final manual (or the implemented adaptation) and/or determining the level of fidelity with the parent intervention. While some may argue that dissemination of ESIs like MI might be more important than attentive adherence to intervention integrity (e.g., W. R. Miller et al., 2007), or that the integrity of the treatment may not be important if patients are experiencing positive outcomes, similar to Interian and colleagues (2010), we believe that formal evaluation of the final manual is critical. Specifically, we recommend administering the final manual to the target adolescent audience and collecting empirical outcome data to determine the efficacy of the adapted intervention approach and to ensure that the active ingredients are still present in the adapted approach (e.g., Castro et al., 2004). These data are informative across several levels; they inform whether the adapted intervention is effective with the adolescent subgroup (e.g., if quantity of alcohol use decreased). Additionally, they highlight whether the adapted intervention is still congruent with the original intervention. In MI, we recommend evaluating both subjective as well as objective perception of the active ingredients. In terms of subjective ratings, we recommend client/provider satisfaction measures (e.g., to what degree did therapists believe they were MI-consistent; to what degree did youth observe the presence or absence of MI-consistent behaviors by their therapist; see Tables 1-2). We also recommend collecting objective behavior counts, because therapists’ ratings of their intervention delivery often do not correlate well with independent coder ratings (e.g., Carroll et al., 2002; Madson & Campbell, 2006; W. R. Miller & Mount, 2001). At this time, several objective integrity measures exist to evaluate the presence of MI components and/or practitioners use of MI-consistent behaviors (e.g., MITI, SCOPE; Moyers & Martin, 2006; Moyers, Martin, Houck, Christopher, & Tonigan, 2009; Moyers, Martin, & Manuel, 2005). While some are slightly better equipped for evaluating MI integrity in adaptations of MI (e.g., BECCI; Lane et al., 2005), one liability of adapting an intervention is that it renders evaluations of integrity a bit more difficult. To that end, if the basic tenets of MI are adapted to improve cultural congruence, then it stands to reason that standard behavioral coding instruments might not work as well with an adapted intervention. Notably, at this time, this remains an empirical question. And, while some research groups have taken steps in this direction, measurement approaches to evaluate MI integrity across adapted interventions still warrant attention.

4. Recommendations for addressing multiculturalism

While mental health treatments have been found to be four times more effective when adapted for the cultural context and values of the specific client (Griner & Smith, 2006), additional external factors must be attended to in order to promote best practice within cultural minority youth, as these factors are also likely to have a role in the complex process of treatment engagement and participation. Specifically, recent studies have highlighted the complex panoply of issues that might challenge otherwise effective child and adolescent interventions (Koinis-Mitchell et al., 2010). Specifically, studies have found that acculturative stress, discrimination, level of economic resources relative to the number of family members in their home, neighborhood stress, belief about the efficacy of treatment and comfort with the intervention approach, migration experiences, and ability to navigate the healthcare system may all contribute to variations in behavior outcomes following treatment, particularly for cultural minority youth (Koinis-Mitchell et al., 2010).

One way to promote attention to these multifaceted issues during the development and implementation of treatment is to retain an active awareness of the ADDRESSING framework (Hays, 2008). As posited by Hays, this acronym serves as reminder that culturally competent treatment with youth includes: age and generational issues, developmental disabilities, disabilities acquired later in life, religion and spiritual orientation, ethnic and racial identity, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, indigenous heritage, national origin, and gender (Hays, 2008).

In addition to retaining an active awareness of the ADDRESSING framework, several broader-level recommendations are warranted for work with cultural minority adolescents. Specifically, clinicians might consider initiating conversations about the adolescent’s beliefs about the ADDRESSING indicators. Specifically, adolescents may differentially identify with specific factors (e.g., being female, generational issues, versus disabilities acquired later in life). Providers would therefore benefit from understanding adolescents’ unique and developing perspectives when tailoring interventions (Hwang, 2006). It may also be helpful for adolescents who have divergent beliefs from their families of origin to receive additional support in implementing behavior change strategies at home and in their communities. Moreover, although individual- and group-level work with adolescents focuses on the adolescent, all work with youth necessarily involves collaboration with families. Thus, it is important for therapists to be conscious of (while being careful not to challenge or condemn) acculturative conflict between children, parents and grandparents, as intergenerational conflict may influence the family, as well as the youth’s treatment engagement, and the youth’s ability to catalyze and sustain behavior change (e.g., Zamboanga, Schwartz, Jarvis, & Van Tyne, 2009). Similarly, it is important to be conscious that families are likely to have a history of (or may currently be) experiencing chronic stressors such as poverty or oppression, and that these experiences may influence both participants’ participation in therapy, as well as their likelihood of being successful in behavior change.

5. Discussion

5.1 Clinical Implications

While many well-intentioned practitioners aim to improve their treatment of cultural minority adolescents, it is difficult to do so without a guiding strategy. At the moment, there is a paucity of literature guiding the use of empirically supported interventions (ESIs) for cultural minority populations (Nagayama Hall, 2001), particularly with youth. And, at this time, many empirical evaluations of ESIs have not explicitly attended to issues of culture, race, and socioeconomic background in their analyses (Duran, Wallerstein, & Miller, 2007). As a result, there is some question about the external validity of ESIs, particularly in disadvantaged cultural minority populations (Duran et al., 2007). Similarly, arguments have been made that a cultural prescriptive approach (e.g., always emphasizing family when working with Hispanic Americans, being careful not to look Native American patients in the eye when treating AIAN clients), although often well-intended, fail to account for the heterogeneity that exists within adolescent cultural groups (W. R. Miller et al., 2007). One way to carefully attend to the needs of diverse cultural groups, particularly with high risk and/or substance abusing youth who may display great ranges in cultural affiliation depending on acculturation, geography, socioeconomic background, and community (Wallace, 1999), is to carefully tailor ESIs, such as MI, to both the cultural and developmental community of youth with whom one works.

While many ESIs’s, including MI, may have foundational approaches (e.g., client-centeredness) that may be consistent across adolescent cultural groups (W. R. Miller et al., 2007), to be truly culturally-sensitive, an adaptation must be specific and responsive to the heterogeneity within an adolescent cultural group (e.g., Cuban Americans vs. Puerto Ricans; Plains Indians vs. Pueblo Indians; North Africans vs. West Africans). Thus, while certain parts of the adaptation might be fundamentally and universally delivered across adolescent cultural groups (e.g., focus on client-centeredness, emphasis on adolescent’s autonomy) (W. R. Miller et al., 2007), as found within S. T. Miller’s recent work (2010), other aspects might need to be more specifically adapted to the needs of the different subpopulation (e.g., tailoring for more prescriptive vs. deductive therapist approaches). Determining how finely to slice adaptation is a critical question. Answering this question involves balancing the effectiveness of the available intervention approach (how well does the intervention work as is? what is the current efficacy?), the benefits of improving adherence (would a further adaptation significantly improve outcomes?), and the amount of time required to adapt the intervention to the cultural subgroup.

Equally important is the issue of treatment delivery. While some large-scale studies have found that matching patients and providers across a number of variables (including ethnicity) did not directly influence treatment outcomes (for better or for worse, e.g., Cabral & Smith, 2011; Suarez-Morales et al., 2010), other adolescent and adult studies have found improved outcomes with matched ethnicity (e.g., Field & Caetano, 2010; Flicker, Waldron, Turner, Brody, & Hops, 2008). A more complicated and compelling question is how to assess cultural knowledge, competence, and congruence both within patients and providers of the same ethnicity, as well as for clinicians providing care across cultural lines. While only a handful of studies have begun to explore these questions (e.g., Nagayama Hall, 2001; Rogers & Lopez, 2002; Sue, Arredondo, & McDavis, 1992), additional studies are clearly needed to evaluate how these factors may influence provider treatment delivery and adolescent treatment outcomes.

5.2 Conclusions and Future Directions

It is our hope that this review will provide practical and feasible guidelines for those aiming to improve their practice with cultural minority youth and adolescents. With its roots in CBPR, the strength of Adapt and Evaluate strongly benefits from the active involvement of the community of interest from the outset. From the beginning, the adolescent and caregiver community has a hand in structuring the foundation of the revised manual and approach, likely increasing the community’s interest and investment in both using and disseminating the final manual (Venner et al., 2007). However, community involvement also requires special considerations. Due to a strained history, community members can be reluctant to work with researchers, meaning that researchers must be careful and attentive in establishing new relationships with cultural communities (Ahmed, Beck, Maurana, & Newton, 2004). Once the research process is underway, care must be taken to balance community objectives with methodological rigor (O’Toole, Felix Aaron, Chin, Horowitz, & Tyson, 2003). And, while approaches exist to effectively tap client satisfaction (subjective report), objective reports (evaluations of integrity) may still need empirical evaluation prior to use. Thus, in Adapt and Evaluate, the challenge rests in ensuring that the active ingredients of the ESI exist after the adaptation (Castro et al., 2004; Interian et al., 2010; Nagayama Hall, 2001). Notably, evaluating outcome data from the final manual is key (Interian et al., 2010).

In contrast, Evaluate and Adapt’s strength lies in its evaluation. Specifically, the original intervention administered could (and should) be subjectively and objectively evaluated using existing empirically supported instruments. And, this approach yields a wealth of quantitative data that highlight both behavioral outcomes, as well as key mechanisms of this approach. However, this quantitative strength is complicated by the nature of design. For example, measurements are limited to the active ingredients that the research group theorizes to be important. Subsequently, it is possible to miss a potentially salient, and culturally-relevant mechanism that may be driving outcomes within the ESI, or that may influence implementation. The onus lies upon the design team to select a range of factors for evaluation, determining reliable and valid instruments to assess them. Finally, while the original intervention can be evaluated for fidelity, similar to Adapt and Evaluate, once the manual has been adapted, evaluating integrity of the final manual is critical.

Summary and Limitations

This review presents two separate approaches for tailoring interventions for cultural minority youth. While these two approaches are presented as independent strategies, there is likely to be a much more iterative and sophisticated relationship between the two. Research teams may choose to begin with Adapt and Evaluate, then choose to move into Evaluate and Adapt to continue to shape their intervention. (Or vice versa).

Additionally, the current review addresses how to approach adaptation with several different cultural and developmental groups, working under the presumption that cultural minority adolescents and their families are interested in (and potentially prescribe) to a western medicalized approach to healthcare. Future work is critical to evaluate how to reach families/children of cultural groups who feel that mental health issues are stigmatizing, or that the “establishment” should not be trusted. For example, within these communities developing relationships with community allies (e.g., churches) might form the first step (preceding even Step 1; Figure 1), and it might be important to determine local needs (e.g., monetary incentives, gift cards) to ensure the enrollment of a more representative sample. Additionally, consistent with the history of historical trauma within AIAN and other cultural minority populations, and recent research (Kelly, 2006), future work would benefit from focusing on recommendations for how to conduct the session with the awareness and attention to the potential presence of historical oppression. Following the work of Koinis-Mitchell and colleagues (2010), future studies would also benefit from active attention to and incorporation of group-level considerations, including family, socioeconomic and political factors, including poverty and oppression, when approaching adaptations. Notably, while the focus of the current review is on adapting MI with cultural minority youth, these approaches are highly applicable to other ESIs, as the active ingredients appear to be consistent across interventions (e.g., Imel, Wampold, Miller, & Fleming, 2008; Moyers, Martin, Houck, Christopher, & Tonigan, 2009), age groups (e.g., Baer et al., 2008), and across target behaviors (Hettema et al., 2005). Thus, while these same approaches appear to have great promise for use with adult populations as well, evaluation with adults is an important next step.

Ultimately, we hope for this review to provide a foundation for those working with cultural minority youth to guide the tailoring of their intervention approaches. With the current state of health disparities in substance abuse treatment (Lowman & Le Fauve, 2003; Russo et al., 2004), active and empirical steps towards improving treatment efficacy with cultural minority youth are critical to reducing existing health disparities.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our adolescent participants and community collaborators for their efforts and for the inspiration. This research was facilitated by a grant to the first author (1R01 AA017878-01A2). Pieces of this review were presented as a talk at the 118th American Psychological Association Convention, in San Diego, CA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aarons GA, Brown SA, Garland AF, Hough RL. Racial/ethnic disparity and correlates of substance abuse service utilization and juvenile justice involvement among adolescents with substance use disorders. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2004;3:47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ahluwalia JS, Okuyemi K, Nollen N, Choi WS, Kaur H, Pulvers K, et al. The effects of nicotine gum and counseling among African American light smokers: A 2 × 2 factorial design. Addiction. 2006;101:883–891. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SM, Beck B, Maurana CA, Newton G. Overcoming barriers to effective community-based participatory research in U.S. medical schools. Education for Health. 2004;17:141–151. doi: 10.1080/13576280410001710969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Carson NJ, Goncalves M, Keefe K. Disparities in treatment for substance use disorders and co-occurring disorders for ethnic/racial minority youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo JA, Miller WR, Tonigan JS. The influence of Hispanic ethnicity on long-term outcome in three alcohol-treatment modalities. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:98–104. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin A, Hospital M, Wagner EF, Morris SL. Motivation for reducing substance use among minority adolescents: Targets for intervention. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010;39:399–407. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Beadnell B, Garrett SB, Hartzler B, Wells EA, Peterson PL. Manuscript under editorial review. University of Washington; 2008. Adolescent change language within a brief motivational intervention and substance use outcomes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Befort CA, Nollen N, Ellerbeck EF, Sullivan DK, Thomas JL, Ahluwalia JS. Motivational interviewing fails to improve outcomes of a behavioral weight loss program for obese African American women: A pilot randomized trial. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;31:367–377. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G. Intervention development and cultural adaptation research with diverse families. Family Process. 2006;45:143–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00087.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Sharron-del-Rio MR. Are empirically supported treatments valid for ethnic minorities? Toward an alternative approach for treatment research. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2001;7:328–342. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.7.4.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan A, Robbins RN, Ruiz MS, O’Neill D. Effectiveness of an HIV prevention intervention in prison among African Americans, Hispanics, and Caucasians. Health Education & Behavior. 2006;33:154–177. doi: 10.1177/1090198105277336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan A, Ruiz MS, O’Neill D. HIV-related behaviors among prison inmates: A theory of Planned Behavior Analysis. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2003;33:2565–2586. [Google Scholar]

- Cabral RR, Smith TB. Racial/ethnic matching of clients and therapists in mental health services: A meta-analytic review of preferences, perceptions, and outcomes. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58:537–554. doi: 10.1037/a0025266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R. Alcohol-related health disparities and treatment-related epidemiological findings among Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics in the United States. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:1337–1339. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000080342.05229.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell PR. Population projections for states by age, sex, race and hispanic origin. 1996:1995–2025. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Farentinos C, Ball SA, Crits-Christoph P, Libby B, Morgenstern J, et al. MET meets the real world: Design issues and clinical strategies in the clinical trials network. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;31:67–73. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00255-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter-Pokras O, Baquet C. What is a “health disparity”? Public Health Rep. 2002;117:426–434. doi: 10.1093/phr/117.5.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera M, Jr., Martinez CR., Jr. The cultural adaptation of prevention interventions: Resolving tensions between fidelity and fit. Prevention Science. 2004;5:41–45. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000013980.12412.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC Center for Disease Control and Prevention: Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey. MMWR. 2010;59:SS–142. [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G, Akers A, Blumenthal C, Council B, Wynn M, Muhammad M, et al. Intervention mapping as a participatory approach to developing an HIV prevention intervention in rural African American communities. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2010;22:184–202. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.3.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross TL, Friesen BJ, Jivanjee P, Gowen LK, Bandurraga A, Matthew C, et al. Defining youth success using culturally appropriate community-based participatory research methods. Best Practices in Mental Health: An International Journal. 2011;7:94–114. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico EJ, Miles JNV, Stern SA, Meredith LS. Brief motivational interviewing for teens at risk of substance use consequences: A randomized pilot study in a primary care clinic. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;35:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico EJ, Osilla KC, Hunter SB. Developing a group motivational interviewing intervention for first-time adolescent offenders at-risk for an alcohol or drug use disorder. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2010;28:417–436. doi: 10.1080/07347324.2010.511076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Lee CH. U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, P60-231, Income Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2005. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, D.C.: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Nelson SE, Kavanagh K. The family check-up with high-risk young adolescents: Preventing early-onset substance use by parent monitoring. Behavior Therapy. 2003;34:553–571. [Google Scholar]

- Domenech-Rodriguez MM, Baumann AA, Schwartz AL. Cultural adaptation of an evidence based intervention: From theory to practice in a Latino/a community context. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;47:170–186. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9371-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran BG, Wallerstein N, Miller WR. New approaches to alcohol interventions among American Indian and Latino communities: The experience of the Southwest Addictions Research Group. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2007;25:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein Ewing SW. Assessing the Fit of Motivational Interviewing by Cultures with Adolescents. the Mind Research Network: NIH/NIAAA. 2011;1R01:AA017878–01A2. [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein Ewing SW, Venner KL, Mead H, Bryan AB. Exploring racial/ethnic differences in substance use: A theory-based investigation with a sample of juvenile justice-involved youth. BMC Pediatrics. 2011;11:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-11-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein SW, Ginsburg JID. Motivational Interviewing with dually diagnosed adolescents in juvenile justice settings Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention. 2006;6:218–233. [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein SW, Ginsburg JID. Sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ rolling with resistance: Motivational Interviewing in juvenile justice settings. In: Roberts AR, Springer DW, editors. Handbook of Forensic Mental Health With Victims and Offenders: Assessment, Treatment, and Research. Charles C. Thomas; New York: 2007. pp. 247–271. [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein SW, Venner KL, May PA. American Indian/Alaska Native alcohol-related incarceration and treatment. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research: The Journal of the National Center. 2006;13:1–22. doi: 10.5820/aian.1303.2006.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field C, Caetano R. Study evaluating ethnic matching in a sample of Hispanics receiving brief, motivational alcohol intervention. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:262–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flicker SM, Waldron HB, Turner CW, Brody JL, Hops H. Ethnic matching and treatment outcome with Hispanic and Anglo substance-abusing adolescents in family therapy. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:439–447. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley K, Duran B, Morris P, Lucero J, Jiang Y, Baxter B, et al. Using Motivational Interviewing to promote HIV testing at an American Indian substance abuse treatment facility. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2005;37:321–329. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2005.10400526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Vlahov D. Social determinants and the health of drug users: Socioeconomic status, homelessness, and incarceration. Public health reports. 2002;117:S135–S144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Lau AS, Yeh M, McCabe KM, Hough RL, Landsverk JA. Racial and ethnic differences in utilization of mental health services among high-risk youths. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1336–1343. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Wagner EF, Tubman JG. Culturally sensitive substance abuse intervention for Hispanic and African American adolescents: empirical examples from the Alcohol Treatment Targeting Adolescents in Need (ATTAIN) Project. Addiction. 2004;99:140–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilder DA, Luna JA, Calac D, Moore RS, Monti PM, Ehlers CL. Acceptability of the use of Motivational Interviewing to reduce underage drinking in a Native American community. Substance use and misuse. 2011;46:836–848. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2010.541963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP. A community-based treatment for Native American historical trauma: Prospects for evidence-based practice. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:751–762. doi: 10.1037/a0015390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griner D, Smith TB. Culturally adapted mental health interventions: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, and Training. 2006;43:531–548. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays PA. Addressing cultural complexities in practice: Assessment, diagnosis, and therapy. 2nd ed. American Psychological Association; Washington, D. C.: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hays PA. Integrating evidence-based practice, cognitive-behavior therapy, and multicultural therapy: Ten steps for culturally competent practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2009;40:354–360. [Google Scholar]

- Hellerstedt WL, Peterson-Hickey M, Rhodes KL, Garwick A. Environmental, social, and personal correlates of having ever had sexual intercourse among American Indian youth. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:2228–2234. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.053454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. A meta-analysis of research on Motivational Interviewing treatment effectiveness (MARMITE) Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:91–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstad MM, DiIorio C, Kelly ME, Resnicow K, Sharma S. Group Motivational Interviewing to promote adherence to antiretroviral medications and risk reduction behaviors in HIV Infected Women. AIDS and Behavior. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9865-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath AO, Greenberg LS. Development and validation of the Working Alliance Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1989;36:223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Huey SJ, Jr., Polo AJ. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for ethnic minority youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:262–301. doi: 10.1080/15374410701820174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang W-C. The psychotherapy adaptation and modification framework: Application to Asian Americans. American Psychologist. 2006;61 doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imel ZE, Wampold BE, Miller SD, Fleming RR. Distinctions wihtout a difference: Direct comparisons of psychotherapies for alcohol use disorders. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:533–543. doi: 10.1037/a0013171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interian A, Martinez I, Rios LI, Krejci J, Guarnaccia PJ. Adaptation of a Motivational Interviewing intervention to improve antidepressant adherence among Latinos. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16:215–225. doi: 10.1037/a0016072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly S. Cognitive-behavioral therapy with African Americans. In: Hays PA, Iwamasa GY, editors. Culturally responsive cognitive-behavioral therapy: Assessment, practice, and supervision. American Psychological Association; Washington, D. C.: 2006. pp. 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk S, Scott BJ, Daniels SR. Pediatric obesity epidemic: treatment options. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2005;105(5 Suppl 1):S44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koinis-Mitchell D, McQuaid EL, Friedman D, Colon A, Soto J, Rivera DV, et al. Latino caregivers’ beliefs about asthma: Causes, symptoms, and practices. J Asthma. 2008;45:205–210. doi: 10.1080/02770900801890422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koinis-Mitchell D, McQuaid EL, Kopel SJ, Esteban CA, Ortega AN, Seifer R, et al. Cultural-related, contextual, and asthma-specific risks associated with asthma morbidity in urban children. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2010;17:38–48. doi: 10.1007/s10880-009-9178-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaChance HA, Feldstein Ewing SW, Bryan A, Hutchison K. What makes group MET work? A randomized controlled trial of college student drinkers in mandated alcohol diversion Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:598–612. doi: 10.1037/a0016633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane C, Huws-Thomas M, Hood K, Rollnick S, Edwards K, Robling M. Measuring adaptions of Motivational Interviewing: The development and validation of the behavior change counseling index (BECCI) Patient Education and Counseling. 2005;56:166–173. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS. Making the case for selective and directed cultural adaptations of evidence-based treatments: Examples from parent training. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006;13:295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Donovan DM, Karno MP, McCrady BS, Morgenstern J, Tonigan JS. Active ingredients: How and why evidence-based alcohol behavioral treatment interventions work. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:235–247. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000153541.78005.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez Viets V. CRAFT: Helping Latino families concerned about a loved one. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2007;25:111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Lowman C, Le Fauve CE. Health disparities and the relationship between race, ethnicity, and substance abuse treatment outcomes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:1324–1326. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000080346.62012.DC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl BW, Kunz C, Brownell C, Tollefson D, Burke BL. A meta-analysis of Motivational Interviewing: Twenty-five years of empirical studies. Research on Social Work Practice. 2010;20:137–160. [Google Scholar]

- Madson MB, Campbell TC. Measures of fidelity in motivational enhancement: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Larimer ME, Mail PD, Hawkins EH, Cummins LH, Blume AW, et al. Journeys of the Circle: A culturally congruent life skills intervention for adolescent Indian drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:1327–1329. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000080345.04590.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G, Copeland J. The adolescent cannabis check-up: Randomized trial of a brief intervention for young cannabis users. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;34:407–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Miller JH, Goodhart KA, Maestas OR, Buckley D, Trujillo PM, et al. Enhanced case management to prevent fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in Northern Plains communities. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2008;12:747–759. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0304-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCambridge J, Slym RL, Strang J. Randomized controlled trial of motivational interviewing compared with drug information and advice for early intervention among young cannabis users. Addiction. 2008;103:1809–1818. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller ST, Marolen KN, Beech BM. Perceptions of physical activity and Motivational Interviewing among rural African-American women with type 2 diabetes. Women’s Health Issues. 2010;20:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Mount KA. A small study of training in Motivational Interviewing: Does one workshop change clinician and client behavior? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2001;29:457–471. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd Edition Guilford Press; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Villanueva M, Tonigan JS, Cuzmar I. Are special treatments needed for special populations? Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2007;25:63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Wilbourne PL. Mesa Grande: A methodological analysis of clinical trials of treatment for alcohol use disorders. Addiction. 2002;97:265–277. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Nakamura R, Bernal G. Including ethnic minorities in mental health intervention research: A practical approach to a long-standing problem. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2003;27:467–486. doi: 10.1023/b:medi.0000005484.26741.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Houck JM, Christopher PJ, Tonigan JS. From insession behaviors to drinking outcomes: A causal chain for motivational interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:1113–1124. doi: 10.1037/a0017189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB. UNM CASAA; Motivational Interviewing Provider Workshop; Albuquerque, NM. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T. Therapist influence on client language during motivational interviewing sessions: Support for a potential causal mechanism. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;30:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Houck JM, Christopher PJ, Tonigan JS. From insession behaviors to drinking outcomes: A causal chain for motivational interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:1113–1124. doi: 10.1037/a0017189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK. Assessing competence in the use of motivational interviewing. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, Zemore SE. Disparities in alcohol-related problems among White, Black, and Hispanic Americans. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33:654–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00880.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Ye Y, Zemore SE, Greenfield TK. Social disadvantage, stress, and alcohol use among Black, Hispanic, and White Americans: Findings from the 2005 U.S. National Alcohol Survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:824–833. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz RF, Mendelson T. Toward evidence-based interventions for diverse populations: The San Francisco General Hospital prevention and treatment manuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:790–799. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naar-King S, Parsons JT, Murphy D, Kolmodin K, Harris DR. A multisite randomized trial of a motivational intervention targeting multiple risks in youth living with HIV: Initial effects on motivation, self-efficacy, and depression. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46:422–428. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagayama Hall GC. Psychotherapy research with ethnic minorities: Empirical, ethical, and conceptual issues. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:502–510. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagayama Hall GC. Psychotherapy research with ethnic minorities: Empirical, ethical, and conceptual issues. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:502–510. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole TP, Felix Aaron K, Chin MH, Horowitz C, Tyson F. Community-based participatory research. Opportunities, challenges, and the need for a common language. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2003;18:592–594. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.30416.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TL, Mausbach B, Lozada R, Staines O,H, Semple SJ, Fraga-Vallejo M, et al. Efficacy of a brief behavioral intervention to promote condom use among female sex workers in Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:2051–2057. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.130096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson PL, Baer JS, Wells EA, Ginzler JA, Garrett SB. Short-term effects of a brief motivational intervention to reduce alcohol and drug risk among homeless adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:254–264. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ProjectMatchResearchGroup Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:7–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Jackson A, Blissett D, Wang T, McCarty F, Rahotep S, et al. Results of the Healthy Body Healthy Spirit Trial. Health Psychology. 2005;24:339–348. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riekert KA, Borrelli B, Bilderback A, Rand CS. The development of a Motivational Interviewing intervention to promote medication adherence among innercity, African-American adolescents with asthma. Patient Education and Counseling. 2011;82:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles RR, Reyes JC, Colón HM, Sahai H, Marrero CA, Matos TD, et al. Effects of combined counseling and case management to reduce HIV risk behaviors among Hispanic drug injectors in Puerto Rico: A randomized controlled study. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;27:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers MR, Lopez EC. Identifying critical cross-cultural school competencies. Journal of School Psychology. 2002;40:115–141. [Google Scholar]

- Russo D, Purohit V, Foudin L, Salin M. Workshop on alcohol use and health disparities 2002: A call to arms. Alcohol. 2004;32:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmiege SJ, Broaddus MR, Levin M, Bryan AD. Randomized trial of group interventions to reduce HIV/STD risk and change theoretical mediators among detained adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:38–50. doi: 10.1037/a0014513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shetgiri R, Kataoka SH, Ryan GW, Askew LM, Chung PJ, Schuster MA. Risk and resilience in Latinos: A community-based participatory research study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;37(6, Suppl 1):S217–S224. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirito A, Monti PM, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Sindelar H, Rohsenow DJ, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a brief motivational intervention for alcohol-positive adoelscents treated in an emergency department. J. Pediatr. 2004;145:396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirito A, Sindelar-Manning H, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Lewander W, Rohsenow DJ, et al. Individual and family motivational interventions for alcohol-positive adolescents treated in an emergency department: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:269–274. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein LA, Clair M, Lebeau R, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Golembeske C, et al. Motivational Interviewing to reduce substance-related consequences: Effects for incarcerated adolescents with depressed mood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.03.023. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern SA, Meredith LS, Gholson J, Gore P, D’Amico EJ. Project CHAT: A brief motivational substance abuse intervention for teens in primary care. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;32:153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Morales L, Martino S, Bedregal L, McCabe BE, Cuzmar IY, Paris M, et al. Do therapist cultural characteristics influence the outcome of substance abuse treatment for Spanish-speaking adults? Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16:199–205. doi: 10.1037/a0016113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Arredondo P, McDavis RJ. Multicultural competencies/standards: A pressing need. Journal of Counseling and Development. 1992;70:477–486. [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo KA, Castañeda E, Martínez D, Gonzalez G. Biological research on drug abuse and addiction in Hispanics: Current status and future directions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;84(Suppl 1):S17–S28. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tubman JG, Gil AG, Wagner EF. Co-occuring substance use and delinquent behavior during early adolescence: Emerging relations and implications for intervention strategies. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2004;31:463–488. [Google Scholar]

- Venner KL, Feldstein SW, Tafoya N. Helping clients feel welcome: Principles of adapting treatment cross-culturally. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2007;25:11–30. doi: 10.1300/J020v25n04_02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva M, Tonigan JS, Miller WR. Response of Native American clients to three treatment methods for alcohol dependence. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2007;6:41–48. doi: 10.1300/J233v06n02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DD, Roffman RA, Stephens RS, Wakana K, Berghuis J. Motivational Enhancement Therapy for adolescent marijuana users: A preliminary randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:628–632. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker S, Treno AJ, Grube JW, Light JM. Ethnic differences in driving after drinking and riding with drinking drivers among adolescents. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:1299–1304. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000080672.05255.6C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JMJ. The social ecology of addiction: Race, risk, and resilience. Pediatrics. 1999;103:1122–1127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton MA, Chermack ST, Shope JT, Bingham CR, Zimmerman MA, Blow FC, et al. Effects of a brief intervention for reducing violence and alcohol misuse among adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;304:527–535. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodall WG, Delaney HD, Kunitz SJ, Westerberg VS, Zhao H. A randomized trial of a DWI intervention program for first offenders: Intervention outcomes and interactions with antisocial personality disorder among a primarily American-Indian sample. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:974–987. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D, Ma GX, Zhou C, Zhou D, Liu A, Poon AN. The effect of a culturally tailored smoking cessation for Chinese American smokers. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2009;11:1448–1457. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Hoven CW, Tiet Q, Kovalenko P, Wicks J. Factors associated with adolescent utilization of alcohol treatment services. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28:353–369. doi: 10.1081/ada-120002978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamboanga BL, Schwartz SJ, Jarvis LH, Van Tyne K. Acculturation and substance use among Hispanic early adolescents: Investigating the mediating roles of acculturative stress and self-esteem. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2009;30:315–333. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0182-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]