Abstract

During the past decade, it has become clear that protein function and regulation are highly dependent upon intracellular localization. Although fluorescent protein variants are ubiquitously used to monitor protein dynamics, localization, and abundance; fluorescent light microscopy techniques often lack the resolution to explore protein heterogeneity and cellular ultrastructure. Several approaches have been developed to identify, characterize, and monitor the spatial localization of proteins and complexes at the sub-organelle level; yet, many of these techniques have not been applied to yeast. Thus, we have constructed a series of cassettes containing codon-optimized epitope tags, fluorescent protein variants that cover the full spectrum of visible light, a TetCys motif used for FlAsH-based localization, and the first evaluation in yeast of a photoswitchable variant – mEos2 – to monitor discrete subpopulations of proteins via confocal microscopy. This series of modules, complete with six different selection markers, provides the optimal flexibility during live-cell imaging and multicolor labeling in vivo. Furthermore, high-resolution imaging techniques include the yeast-enhanced TetCys motif that is compatible with diaminobenzidine photooxidation used for protein localization by electron microscopy and mEos2 that is ideal for super-resolution microscopy. We have examined the utility of our cassettes by analyzing all probes fused to the C-terminus of Sec61, a polytopic membrane protein of the endoplasmic reticulum of moderate protein concentration, in order to directly compare fluorescent probes, their utility and technical applications. Our series of cassettes expand the repertoire of molecular tools available to advance targeted spatiotemporal investigations using multiple live-cell, super-resolution or electron microscopy imaging techniques.

Keywords: FlAsH, mEos2, GFP variants, mCherry, pFA6a plasmid, zeocin

Introduction

The sequenced, annotated genome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Goffeau, et al., 1996) has enabled significant insights into biological phenomena (Ghaemmaghami, et al., 2003; Howson, et al., 2005; Huh, et al., 2003) promoting its use as a model eukaryote. Various characteristics that advance rigorous genetic and biochemical analysis of budding yeast include the facile modification of chromosomal DNA by directed one-step integration or deletion with PCR products (Baudin, et al., 1993; McElver and Weber, 1992; Wach, et al., 1994). As such, homologous recombination allows for a variety of gene modifications (Rothstein, 1991); includes the ability to fuse any tag of interest to a protein under the expression of its native promoter within the chromosome; and is a highly efficient approach to the functional analysis of protein fusions.

In this post-genomic era, the study of cell physiology has focused on protein structure, functional interactions, and sub-cellular localization. Accordingly, numerous cassettes have been designed to include epitope tags for protein purification, immunoprecipitation, and immunofluorescence (Funakoshi and Hochstrasser, 2009; Gerami-Nejad, et al., 2009; Moqtaderi and Struhl, 2008). To monitor protein dynamics in living cells, Aequoria victoria green fluorescent protein (GFP) and Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein (DsRed) variants have been extensively utilized in yeast (Gerami-Nejad, et al., 2001; Hailey, et al., 2002; Schaub, et al., 2006), facilitating live-cell imaging techniques. To selectively mark and track the movement of molecules, photoactivatable GFP (PA-GFP) has led to new structural insights governing the mechanisms associated with cortical patch assembly in yeast (Vorvis, et al., 2008).

Engineered fluorescent proteins (FPs) provide a diverse array of tools for biological imaging and in vivo studies (Lippincott-Schwartz and Patterson, 2003; Lippincott-Schwartz and Patterson, 2009; Lukyanov, et al., 2005; Shaner, et al., 2005). In the model yeast organism, S. cerevisiae, techniques such as fluorescence loss in photobleaching (FLIP) and fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) enables the evaluation of protein dynamics and kinetics (Luedeke, et al., 2005; Mc Intyre, et al., 2007; Muller, et al., 2005; Raicu, et al., 2005); fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based technology facilitates studies of protein-protein interactions (Hailey, et al., 2002; Malinska, et al., 2004; Qiu, et al., 2008; Sprouse, et al., 2008); and the application of fluorescent proteins with different spectral characteristics permits simultaneous imaging of multiple proteins at the sub-cellular level (Melloy, et al., 2007; Reinke, et al., 2004; Szymanski, et al., 2007; Takeda and Nakano, 2008).

Visualizing cellular components with high specificity by multicolor fluorescent light microscopy has provided enhanced insights to our understanding of cell biology. However, the utility of fluorescent light microscopy has been constrained by the fundamental limitation of optical microscopy. Due to the intrinsic limit of spatial resolution, sub-cellular structures are beyond the low-resolution limit of fluorescent light microscopy. For example, objects closer than approximately 250 nm apart cannot be resolved when evaluating fluorescent proteins whose excitation and emission wavelengths are within the visible spectrum (Schermelleh, et al., 2008). To circumvent this limitation, high-resolution techniques that include correlated light and electron microscopy methods, as well as emerging super-resolution microscopy applications have been used (Caplan, et al., 2011). Combined with novel FPs, high-resolution techniques have resolved protein localization at the sub-organelle level, enabling determination of protein heterogeneity in cells (Betzig, et al., 2006).

The development of photoactivatable, photoswitchable and photoconvertible FPs, specifically PA-GFP (Patterson and Lippincott-Schwartz, 2004), EosFP (Wiedenmann, et al., 2004), Dendra (Gurskaya, et al., 2006), Kaede (Ando, et al., 2002), and PS-CFP (Chudakov, et al., 2004), permits investigation into the fate of discrete subpopulations of tagged proteins and dynamics. Monomeric photoconvertible FPs, specifically mEos2 (McKinney, et al., 2009), have been demonstrated for super-resolution techniques such as photoactivated localization microscopy (PALM) (Betzig, et al., 2006) and fluorescence photoactivated localization microscopy (F-PALM) (Hess, et al., 2006; Hess, et al., 2007). Up to ~ 10 nm localization precision has been achieved thereby providing spatiotemporal resolution at the sub-organelle level. Subdiffraction-resolution optical microscopy methods also include stimulated emission depletion microscopy (STED) that attains ~ 70 nm lateral resolution with genetically encoded markers such as GFP (Willig, et al., 2006) and structured illumination microscopy (SIM) that achieves < 50 nm lateral resolution (Gustafsson, 2005). Similarly, three-dimensional SIM (3D-SIM) permits the detection of three fluorescent probes of varying spectra in the same sample while achieving an approximate two-fold enhanced resolution over conventional fluorescence imaging techniques in both the lateral and axial directions (Schermelleh, et al., 2008) thereby resolving the distributions of molecular components within entire organelles, promoting improvements in quantitative measurements, and detection of novel features at the nanoscale level.

As an alternative to FP technology, a six amino acid, tetracysteine motif (e.g. Cys-Cys-Pro-Gly-Cys-Cys) forms a stable complex to a fluorescein derivative, fluorescein arsenical helix binder (FlAsH) (Adams, et al., 2002; Griffin, et al., 1998) that can be used for live-cell imaging. Commonly referred to as a FlAsH tag (Janke, et al., 2004), the TetCys motif and select reagents have been used for correlated optical and electron microscopy photooxidation techniques without requirement for gold-labeling nanoparticles (Gaietta, et al., 2002) in order to extract precise spatial localization of fluorescent molecules at the ultrastructural level. Subsequently, the TetCys motif and corresponding high-resolution microscopy methods allow for a greater specificity than gold-particle labeling and permit investigations in two and three dimensions of the cell (Grabenbauer, et al., 2005).

In this paper, we describe a set of 35 plasmids containing 9 fluorescent variants spanning the visible spectrum that can be used for multicolor imaging. FP variants (Sheff and Thorn, 2004), c-myc and HA epitope tags, and the TetCys motif of the FlAsH tag have been codon-optimized for yeast. To our knowledge, this is the first study for which the yeast-enhanced c-myc, HA, and FlAsH tag maintain optimal sequences for S. cerevisiae (Nakamura, et al., 2000). Prior to this study, Andresen and colleagues (2004) investigated the functionality of β-tubulin in S. cerevisiae by comparing its expression fused to either the GFP or FlAsH tag; we have further identified its use when fused to a polytopic membrane protein of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) whose C-terminus is exposed to the cytosol. We also utilized for the first time a photoswitchable green-to-red variant, mEos2, in yeast while analyzing its expression and fluorescent properties. Furthermore, we have increased the repertoire of selection markers in S. cerevisiae by incorporating the Streptoalloteichus hindustanus bleomycin (Sh ble) gene that confers resistance to Zeocin™, as previously published (Frazer and O’Keefe, 2007; Papakonstantinou, et al., 2009). Each cassette is available with a kanMX or hphMX4 gene, in addition to the following selective marker genes TRP1, LEU2, or URA3 used with appropriate auxotrophic yeast strains while maintaining primer homology consistent with established cassettes derived from pFA6a. We have demonstrated the utility of this cassette series by labeling Sec61, an essential subunit of the ER translocon, with all novel tags and provided a direct comparison among fluorescent proteins, FlAsH tag, and photoconvertible mEos2. Combined, these modules provide optimal fluorescence spectra and selections for multicolor labeling in vivo, specify a range of fluorophores in order to compare the effects of size and resultant functionality, and include numerous tags to analyze protein distribution compatible with confocal microscopy, electron microscopy, correlative light and electron microscopy, and super-resolution microscopy. As a result of locating different molecules or structures in multiple dimensions with techniques that surpass the resolution of fluorescent light microscopy, interesting new perspectives regarding cell function and regulation have been hypothesized and will lead to a more in-depth understanding of spatial cell biology.

Materials and Methods

Construction of Plasmid Cassettes

Details associated with the molecular engineering of novel cassettes are summarized in Table S1. Similarly, key components of these versatile modules are depicted in Figure 1. A comprehensive overview of all available C-terminal tagging cassettes, identifying both the tag and selection marker, is provided in Table S2. Corresponding oligonucleotides synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA) are listed in Table S3.

Figure 1. Comprehensive overview depicts key components of pCY cassettes.

(A) Plasmid map of the template used for this series of tagging constructs. (B) Generalized nucleotide sequence of all pCY cassettes, similar to other series of commonly used modules derived from pFA6a-GFP(S65T) (Wach, et al., 1994). Sequences used to amplify specific tags and selection markers are denoted in italics. Restriction sites have been identified and corresponding nucleotides underlined. A polylinker has been designed based on frequently used codons of S. cerevisiae (Nakamura, et al., 2000) denoted by frequency (i.e percentage of codon usage within the entire genome) and inserted between XmaI and the original PacI restriction site, thereby eliminating its uniqueness. The ADH1 terminator (TADH1) of S. cerevisiae is a component of all pCY plasmids derived from pBS7 (Yeast Resource Center); however, it is not in cassettes derived from pBS10 or pBS35 (Yeast Resource Center), a design similar to Janke and colleagues (2004). (C) Arrangement of all blue, green, yellow, and red fluorescent variants of the pCY series, in addition to variants combined with multiple epitope tags, and a photoswitchable FP (i.e. mEos2) used in our studies. (D) Epitope tags, c-myc and HA, are codon-optimized (i.e. yeast-enhanced (yE)) sequences; specific residues that maintain affinity for commercial antibodies are in bold. A yeast-enhanced TetCys motif common to FlAsH-based technology has been constructed; the optimal sequence used with Lumio™ In-cell Labeling kit (invitrogen™) is shown as bold font. (E) General design for forward and reverse primers using standard homologous recombination techniques.

Plasmids pBS7, pBS10, and pBS35 ((Hailey, et al., 2002), Yeast Resource Center, University of Washington) derived from pFA6a-GFP(S65T)-kanMX (Wach, et al., 1997) were used as the parental vectors for all cassettes identified in Table S1. Yeast codon-optimized GFP variants were amplified from the pKT series of vectors (Sheff and Thorn, 2004) and photoconvertible fusion protein, mEos2, from pRSETa (McKinney, et al., 2009) by primers specified in Tables S1 and S3. Selective residue mutations corresponding to fluorescent variants are detailed in Table S4. In many cases, a two-step ligation process was essential in order to first insert the fluorescent protein or epitope tag into the base construct at the BamHI and BssHII restriction sites, followed by the insertion of a yeast-enhanced polylinker (Sheff and Thorn, 2004) at the 5′ end of selective tags using XmaI and PacI (Figure 1 A, B). To determine the appropriate construct to be sequenced (DNA Sequencing Facility, University of Pennsylvania), the codon-optimized polylinker was designed with a unique AflII site (Table S3).As a result of molecular engineering design, the first generation of recombinant fusion proteins required DNA amplification of tags using forward primer HFR1 (Table S3); however, with the addition of the codon-optimized polylinker the homology of forward primer HFR2 is conserved in all cassettes (Figure 1 E, Table S3, Addgene). Only cassettes containing the yEpolylinker have been provided to the non-profit plasmid repository Addgene (http://www.addgene.org); furthermore, only one set of primers is required for cassette amplification within the pCY series.

As shown in Figure 1 D and defined in Table S3, two complementary oligonucleotides encoding yeast enhanced c-myc and HA epitope tags, as well as an optimized tetracysteine motif (i.e. Cys-Cys-Pro-Gly-Cys-Cys) to implement FlAsH (Fluorescein Arsenical Hairpin) technology, contain a 5′ BamHI and 3′ BssHII site. Complementary oligonucleotides were mixed in distilled water at 10 μM final concentrations and heated to 94°C for 2 min, 92°C for 10 sec, 65°C for 15 min, then stored at 4°C until use (PTC-200 Thermal Cycler PCR system, MJ Research). The resultant double-stranded DNA fragment was incubated with pBS7, pBS10, or pBS35 restricted vector and ligated with T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs) per manufacturer’s instructions.

Parental vector pBS7 (Yeast Resource Center, University of Washington) maintains kanamycin resistance by inclusion of the kanMX (Wach, et al., 1994) open reading frame (ORF) and pBS10 (and pBS35; Yeast Resource Center, University of Washington) confers resistance to the antibiotic hygromycin B (hph) with respect to the hphMX4 gene (Goldstein and McCusker, 1999). We included a novel dominant antibiotic resistant gene Sh ble that confers resistance to Zeocin™. A TEF promoter and terminator flank the zeocin resistance gene (i.e. Sh ble) amplified from plasmid pPICZ A (invitrogen™), a design similar to cassettes constructed by Goldstein and McCusker (1999). Additionally, selection in auxotrophic strains is realizable by inclusion of S. cerevisiaeendogenous promoters through terminators of TRP1 (i.e. HincII – PstI), LEU2 (i.e. XhoI – SalI), and URA3 (HindIII – SmaI) from plasmids pRS314, pRS315, and pRS316 (Sikorski and Hieter, 1989), respectively. Details are provided in Tables S1 and S3.

Escherichia coli strain DH5α and standard techniques were used for DNA manipulations (Seidman, et al., 2001). DNA fragments were excised from agarose gels and purified by Zymoclean™ Gel DNA Recovery kit (Zymo Research) or Wizard® SV Gel and PCR Clean-up System (Promega). Preparation of plasmid DNA was completed using Zyppy™ Plasmid Miniprep kit (Zymo Research) or Wizard® Plus SV minipreps DNA Purification System (Promega).

Yeast Strains, Growth Conditions, and Validation

Yeast strains BJ5464 (MATα ura3-52 trp1 leu2Δ his3Δ200 pep4::HIS3 prb1-Δ1.6R can1 GAL, ATCC 208288, (Jones, 1991)), BY4742 (MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0, EUROSCARF Y1000, (Brachmann, et al., 1998)), and derivatives listed in Table 1 were used in this study. S. cerevisiae strain BJ5464 lacks efficient vacuolar degradation due to the deletion of PEP4 and PRB1 and is predominantly used for heterologous protein expression; BY4742 is typically used to evaluate endogenous cellular processes and protein function. Our research interests encompass many aspects of protein folding, trafficking, and cellular quality control; therefore we investigated both strains expressing the ER translocon, Sec61, with all novel cassettes. YPD and synthetic drop-out media were prepared as described (Sherman, 2002). As previously demonstrated, primers used for chromosomal insertion require ~ 40 bp homology to the genome and ~ 20 bp homology to the desired cassette (Longtine, et al., 1998; Wach, et al., 1997). Similarly, C-terminal fusion proteins expressed from their endogenous promoters were created by amplification of selective modules and ultimately targeted to the Sec61 ORF by homologous recombination (Figure 1E, Table S3). Select regions of modules were amplified using the Expand Long Template PCR System (Roche) and Buffer 3 under conditions provided (http://depts.washington.edu/yeastrc/pages/plasmids_protocols.html) with the exception that the annealing temperature for all PCR reactions was 57°C. Amplified DNA (45 μL) was used for yeast transformations as described in the Yeast Resource Center protocol, a modified version of Gietz and Woods (Gietz and Woods, 2002) High-Efficiency Transformation Protocol. To increase overall efficiency of the yeast transformations, following incubation at 42°C and centrifugation (8,000 rcf, 1 min), cells were resuspended in 3 mLs of YPD and placed in a water shaker for 3-5 hrs at 30°C and 275 rpm. Approximately 0.5 – 1.5 mLs were centrifuged at 8,000 rcf for 1 min; 150 μLs were resuspended and plated to the appropriate media. To select for antibiotic resistant transformants, the following concentrations of antibiotics were added to standard YPD plates: kanMX, geneticin® (G418, Gibco), 200 μg/mL; hphMX4, hygromycin B in PBS (invitrogen™), 300 μg/mL; and zeocin resistant gene Sh ble, Zeocin™ (invitrogen™), 200 μg/mL. Antibiotics were added when the media reached a temperature below 60°C. To increase the probability of obtaining correct integrations, selection for positive transformants was accomplished by replica plating at increased concentrations of geneticin® (1.0 mg/mL), hygromycin B (0.75 mg/mL), or Zeocin™ (0.5 mg/mL). To select fusion proteins based on TRP1, LEU2, or URA3 genes, appropriate auxotrophic S. cerevisiae strains were transformed and synthetic complete (SC) plates lacking tryptophan, leucine, or uracil were prepared as described (Sherman, 2002). Integration success was initially tested by in-gel fluorescence of GFP variants, mCherry, or mEos2, and then confirmed by immunoblotting and genomic PCR. Genomic DNA was extracted using MasterPure™ Yeast DNA Purification kit (EPICENTRE® Biotechnologies) and amplified with primers listed in Table S3 in combination with KOD Hot Start Master Mix (Novagen®). Correct sequencing of genomic DNA was also confirmed for a fraction of novel strains.

Table 1.

S.cerevisiae strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Primers | Source/[Reference] |

|---|---|---|---|

| BJ5464 | MATα ura3-52 trp1 leu2Δ his3Δ200 pep4∷HIS3 prb1-Δ1.6R can1 GAL | --- | ATCC® 208288™/ (Jones, 1991) |

| CY2001 | MATα ura3-52 trp1 leu2Δ his3Δ200 pep4∷HIS3 prb1-Δ1.6R can1 GAL SEC61-Venus∷kanMX | HRF1 Sec61, HRR Sec61 | This study |

| CY2002 | MATα ura3-52 trp1 leu2Δ his3Δ200 pep4∷HIS3 prb1-Δ1.6R can1 GAL SEC61-yEpolylinker-yEVenus∷kanMX | HRF2 Sec61, HRR Sec61 | This study |

| CY2003 | MATα ura3-52 trp1 leu2Δ his3Δ200 pep4∷HIS3 prb1-Δ1.6R can1 GAL SEC61-yEpolylinker-yECitrine∷kanMX | HRF2 Sec61, HRR Sec61 | This study |

| CY2004 | MATα ura3-52 trp1 leu2Δ his3Δ200 pep4∷HIS3 prb1-Δ1.6R can1 GAL SEC61-yEpolylinker-yEmCitrine∷kanMX | HRF2 Sec61, HRR Sec61 | This study |

| CY2005 | MATα ura3-52 trp1 leu2Δ his3Δ200 pep4∷HIS3 prb1-Δ1.6R can1 GAL SEC61-yEpolylinker-yEGFP∷kanMX | HRF2 Sec61, HRR Sec61 | This study |

| CY2006 | MATα ura3-52 trp1 leu2Δ his3Δ200 pep4∷HIS3 prb1-Δ1.6R can1 GAL SEC61-mCherry∷hphMX4 | HRF1 Sec61, HRR Sec61 | This study |

| BY4742 | MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 | --- | EUROSCARF Y1000/ (Brachmann, et al., 1998) |

| CY6001 | MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 SEC61-yEpolylinker-yEmCitrine∷kanMX | HRF2 Sec61, HRR Sec61 | This study |

| CY6002 | MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 SEC61-yEpolylinker-yEGFP∷kanMX | HRF2 Sec61, HRR Sec61 | This study |

| CY6003 | MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 SEC61-yEpolylinker-mCherry∷hphMX4 | HRF2 Sec61, HRR Sec61 | This study |

| CY6004 | MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 SEC61-yEFlAsH∷kanMX | HRF1 Sec61, HRR Sec61 | This study |

| CY6005 | MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 SEC61-yEpolylinker-mEos2∷kanMX | HRF2 Sec61, HRR Sec61 | This study |

EUROSCARF (European Saccharomyces cerevisiae Archive for Functional Analysis)

In-gel Fluorescence

The fluorescence of GFP variants, mCherry, or mEos2 was used in preliminary assays to analyze the expression of endogenous fusion proteins. A detailed protocol has been described elsewhere (Young, et al., 2011). Briefly, overnight cultures of each sample were grown to mid-log phase (0.8 ≤ OD600 ≤ 1.0) in 5 mLs of YPD media (30°C, 275 rpm). For each sample, a volume equivalent to 1 OD of cells for Sec61-GFP variants, or 5 ODs for mEos2 and mCherry fusion proteins, was removed and centrifuged for 1 min at 13,000 rcf. Supernatant was discarded, followed by the addition of 100 μL of lysis buffer (1% SDS, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH = 7.4, complete, EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche), per manufacturer’s instructions), adapted from Rothblatt and Schekman (1989). An equal volume of glass beads (0.5 mm Zirconia/Silica beads, Biospec Products, Inc.) was added to the cell lysis, then the combined volumes were vortexed at high speed for 30 sec followed by a minimum of 30 sec on ice. These alternating cycles were repeated two additional times. Cell lysates were retrieved and clarified by centrifugation at 16,000 rcf for 1 min. Lysate was combined with 3 x SDS loading buffer (150 mM Tris, pH = 6.8; 0.25 mg/mL bromophenol blue; 6% SDS; 30% glycerol) and proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Gels were then scanned (Typhoon 9400 Variable Mode Imager, Amersham Biosciences) at 488 nm excitation wavelength with a 520BP40 filter or 532 nm excitation wavelength with a 580BP30 filter. A fluorescent molecular weight ladder at 488 nm (Benchmark™ Fluorescent Protein Standard, invitrogen™) was used as a standard.

Western blot Analysis

Yeast extracts were prepared as described in the previous section with the following modifications: a volume equivalent to 1 OD of cells for all Sec61 fusions was removed and the resultant lysis was combined with 3 x SDS loading buffer (150 mM Tris, pH = 6.8; 0.25 mg/mL bromophenol blue; 6% SDS; 30% glycerol; 100 mM DTT) then heated at 60°C for 5 to 10 min. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, electrotransferred to Trans-Blot® Transfer Medium pure nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad), and probed by standard Western blot procedures (Gallagher, et al., 2004). Primary antibodies rabbit anti-GFP (polyclonal antibody, ab6556, 1:5000, abcam®) and mouse anti-β-actin (monoclonal – loading control, ab8224, 1:2000, abcam®) were followed by incubation with secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor® 633 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (invitrogen™) and Alexa Fluor® 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (invitrogen™) at 1:2500 and 1:1500 dilutions, respectively. Blots were then scanned (Typhoon 9400 Variable Mode Imager, Amersham Biosciences) and analyzed at the desired settings of 488 nm excitation wavelength and filter 520BP40 or 633 nm excitation and filter 670BP30.

Spectroscopic Studies: Confocal Microscopy and Photoactivated Localization Microscopy (PALM)

Live-cell Imaging

Confocal microscopy for all green and yellow fluorescent variants was performed on a Zeiss LSM 5 DUO using an alpha Plan-Aprochromat 100x/1.46 NA oil immersion objective. Optimized imaging techniques were completed for endogenous Sec61 fusion proteins consisting of mCherry, mEos2, and FlAsH on a Zeiss LSM780 confocal microscope (100x/NA 1.46 objective) due to the increased sensitivity of its gallium arsenide-phosphide (GaAsP) detectors. Growth conditions were identical to those described above. When mid-log phase was achieved, 1 mL of culture was removed, centrifuged at 8,000 rcf for 1 min, and rinsed twice with SC media. Cells were then embedded in 2% agarose (SeaPlaque® GTG® Agarose, LONZA) dissolved in SC media and coated with VALAP (1 vaseline: 1 lanolin: 1 parrafin) for live-cell imaging. In particular, the use of SC media is highly recommended to minimize autofluorescence during live-cell imaging of yeast.

Sec61 fused to yEGFP was excited at 488 nm and imaged with 8 line averages on the Zeiss LSM 5 DUO (filter: LB505; beam splitters: HFT488, NFT 565); yellow variants were excited at 514 nm and imaged with 8 line averages under the following settings: LP530 filter; HFT 458/514/561 and NFT 515 beam splitters. Live-cell images of Sec61 mCherry fusions were completed on the Zeiss LSM 780 at the following parameter settings: excitation at 561 nm; 16 line averages; 577 – 691 nm emission; and MBS 488/561 beam splitter.

Single-cell Analysis of Fluorescence Intensity

In order to quantify the relative fluorescence intensity of GFP variants between Sec61 fusions, initially whole-cell fluorescence techniques were attempted. As a result of Sec61’s moderate protein concentration and lack of instrument sensitivity compared to the autofluorescence of parental strains, we concluded that whole-cell fluorescence is an inappropriate method of evaluation due to significant experimental error. The sensitivity of detection using confocal microscopy promoted an alternative approach - quantifying the fluorescence intensity of individual cells in the population. To calculate a normalized intensity per cell, the fluorescence of representative samples (N > 30) was measured then divided by corresponding area. Data shown are the average, normalized fluorescence intensities with standard errors (SE) of all yellow GFP variants (Table 2). Details pertaining to selection of microscope, objective, and settings have been defined in relevant sections. Quantifying fluorescence by analyzing individual cells within a population was completed using ImageJ applications (Abramoff, et al., 2004; Rasband, 1997-2008).

Table 2.

Fluorescence intensity comparisons of yellow GFP variants fused to Sec61

| Identification of Recombinant Sec61 Strains | Normalized Fluorescence (AU) ± SE | N |

|---|---|---|

| Sec61-yEpolylinker-yEmCitrine | 1100 ± 18 | 150 |

| Sec61-yEpolylinker-yECitrine | 940 ± 13 | 60 |

| Sec61-yEpolylinker-yEVenus | 570 ± 12 | 105 |

| Sec61-Venus | 400 ± 19 | 33 |

AU denotes arbitrary units, SE is defined as the standard error of the mean, and N is the total number of cells analyzed

FlAsH In-Cell Labeling Technique

To facilitate site-specific fluorescent labeling of recombinant proteins expressing an optimized TetCys motif (Figure 1 D), the Lumio™ In-Cell Labeling kit (invitrogen™) was used in conjunction with a modified protocol developed by Andresen and colleagues (2004). BY4742 Sec61-yEFlAsH and parental strain BY4742 were grown overnight to mid-log phase (1.0 ≤ OD600 ≤ 2.5) in 5 mLs of YPD (30°C, 275 rpm). Approximately 20 μL of each culture was diluted to fresh media (VT = 200 μL) in addition to final concentrations of the following reagents: 5 μM EDT (1,2-ethanedithiol, SIGMA-ALDRICH®), 2 μM FlAsH reagent (Lumio™ Green, invitrogen™), and Disperse Blue 3 (Lumio™ Green In-cell Labeling kit, invitrogen™) at 30°C, 275 rpm and varying incubation times (e.g. 30 min, 60 min, and 90 min) per manufacturer’s instructions. To remove non-specifically bound FlAsH reagent, the cells were resuspended in 1 mL of SC media with 50 μM EDT and placed on a rotating wheel for ~ 10 min in the dark. Cells were centrifuged for 1 min at 8,000 rcf, resuspended with 1 mL of SC media in the absence of EDT, and prepared for live-cell imaging as described above.

To detect fluorescent labeling of the FlAsH reagent, the endogenous Sec61 fusion protein consisting of the TetCys motif as well as the parental strain were analyzed under identical parameter settings of the Zeiss 780 confocal microscope: excitation at 488 nm; 16 line averages; 498 – 586 nm emission; and MBS 488/561 beam splitter.

mEos2 Photoswitchable Experiments

Photoswitchable mEos2 represents a convenient tool to facilitate protein-tracking studies in yeast. Excitation and emission spectra profiles of native (green) species of mEos2 display maxima at 506 nm and 519 nm, respectively. Photoconversion of mEos2 is accomplished by stimulation at 405 nm resulting in a red (photoconverted) species of mEos2 that displays maximum excitation and emission spectra at 573 nm and 584 nm, respectively (McKinney, et al., 2009). Sec61-yEpolylinker-mEos2, as well as Sec61-yEpolylinker-yEGFP, was analyzed at identical confocal parameters in order to determine the efficiency of photoconversion and detection of autofluorescence exhibited in the red channel of mEos2 prior to illumination.

Time series analysis was completed on the Zeiss LSM 780 confocal microscope using the following parameter settings: (a) excitation of the native (green) species at 488 nm, 4% laser power, and GaAsP spectral detector; 16 line averages; 490 – 577 filter; MBS 488/561 and MBS 405 beam splitters; (b) illumination at 405 nm with twenty iterations at 10% laser power following the initial scan (i.e. controlled sample) resulted in a converted (red) species; (c) excitation of photoconverted species excited at 561 nm, 4% laser power, and GaAsP spectral detector; 16 line averages; 490 – 577 filter; MBS 488/561 and MBS 405 beam splitters.

Interestingly, when cultures of BY4742 Sec61-yEpolylinker-mEos2 were grown overnight to mid-log phase (0.8 ≤ OD600 ≤ 1.5) in 5 mLs of YPD (30°C, 275 rpm), the desired product was not adequately visible. mEos2 fusions were only detected when cells were taken directly from an incubated plate at 30°C, resuspended in SC media, and prepared for live-cell imaging as previously described.

Super-Resolution Microscopy in Yeast using Photoactivated Localization Microscopy (PALM)

BY4742 Sec61-yEpolylinker-mEos2 cells were grown overnight on an YPD plate incubated at 30°C and resuspended in 1 mL PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline, 1.44 g/L NaCl, 0.2 g/L KCl, 0.24 g/L KH2PO4, 8 g/L NaCl, pH=7.35). Fixation was completed in paraformaldehyde (4% final concentration, EM grade paraformaldehyde, Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were centrifuged for 1 min at 8,000 rcf, rinsed three times with PBS, and then immobilized to cover slips coated with poly-D-lysine (0.1% final concentration, MW > 300,000, SIGMA-ALDRICH®). Fixed Sec61-yEpolylinker-mEos2 cells were immersed in PBS and imaged the following day.

Imaging was performed on a Zeiss ELYRA PS.1 system. Before imaging, the sample was incubated with gold particles to be used as fiducial markers (30 min, 1:10 dilution, 100 nm, BBI international). Subcellular localization of Sec61 mEos2 fusion proteins was identified by imaging the unconverted mEos2 with 488 nm laser excitation. PALM imaging was performed at 31 ms exposure time (512 × 512 pixel, 100 nm/pixel, Andor iXon 896) and 40 mW of 561 nm excitation under objective-launched TIRF or widefield illumination. The ELYRA HP power mode produced a 561 nm laser power density of approximately 2 kW/cm2 in the sample plane. During acquisition, the activation laser was continuously on and manually controlled to a maximum 600 μW power in the sample plane. Fiducial markers were used both during acquisition to correct for z-drift and during post-processing to correct for x-y drift. Total acquisition time was 30,000 frames, or roughly 15 min at 32 Hz.

Distribution of Plasmids

The full collection of plasmids and their sequences are available to non-commercial recipients at the non-profit plasmid repository Addgene (http://www.addgene.org).

Results and Discussion

Versatile Cassette Design and Implementation

Our research interests focus on protein co-localization, as well as protein re-distribution at the sub-organelle level as a consequence of environmental stressors. Thus, to monitor the dynamics of multiple endogenous proteins concurrently and evaluate protein heterogeneity as a result of external stimuli, we developed a series of cassettes with exceptional function and versatility. This series of cassettes enables PCR-based gene modification at the C-terminus in yeast and significantly expands the repertoire of available modules used to analyze protein interactions, dynamics, and cellular localization at varying levels of spatiotemporal resolution.

To promote the utility of our PCR-based modules (Figure 1 C and D, Tables S1 and S2), cassettes were designed with several considerations and numerous techniques were employed to confirm their utility. First, inclusion of GFP variants results in well-separated spectra for multicolor imaging (Sheff and Thorn, 2004). Until now, resolving protein complexes at the sub-organelle level typically required modules that combined epitope tags with fluorescent proteins (FPs), whereas antibodies then distinguished selective targets at electron microscopy resolution through correlative methods (Caplan, et al., 2011). Recently, emerging high-resolution techniques (e.g. SIM and STED) have demonstrated that nanoscale resolution can be realized with engineered FPs - revealing novel structures resolved by high-resolution techniques that were previously not discerned by conventional microscopy (Gustafsson, 2005; Schermelleh, et al., 2008; Willig, et al., 2006). Second, due to the large size of fluorescent variants, FPs may result in mislocalization or decreased functionality of tagged proteins; therefore, we incorporated a codon-optimized TetCys motif to be used with FlAsH-based technology. Furthermore, we demonstrated the usefulness of a photoconvertible fluorescent protein - mEos2 – localized to the ER. Our experimental studies with mEos2 fusions mark the first time this photoconvertible protein has been published in yeast; confirm its use to monitor protein dynamics of discrete subpopulations; and enable visualization of endogenous protein complexes using high-resolution techniques, such as PALM and F-PALM, with S. cerevisiae.

With respect to cassette design, the introduction of a flexible linker between the target protein and tag has led to improved function (Sabourin, et al., 2007) and purification (Funakoshi and Hochstrasser, 2009) of epitope-tagged proteins in S. cerevisiae. Furthermore, the implementation of a yeast-enhanced (yE) or codon-optimized linker resulted in fusion proteins with a two-fold increase in detectable fluorescence (Sheff and Thorn, 2004). Therefore, codon-optimization was emphasized in our designs, specifically a yeast-enhanced polylinker and tags have been used. Particularly advantageous are cassettes designed with common regions of primer homology, thus enabling a single set of oligonucleotides to incorporate any epitope tag (Janke, et al., 2004; Knop, et al., 1999; Longtine, et al., 1998; Sung, et al., 2008; Wach, et al., 1994); and heterologous selection markers that allow for multiple integrations in a strain (Goldstein and McCusker, 1999; Knop, et al., 1999; Longtine, et al., 1998; Wach, et al., 1997). Consequently, a single set of primers may be used with all cassettes regardless of desired tag or selection marker. In addition, multiple antibiotic and auxotrophic selection markers were constructed in order to investigate the dynamics and spatial localization of up to six recombinant proteins simultaneously.

Comparison of Fluorescent Protein Variants to FlAsH-based Technology using an Ideal Endogenous Protein

To demonstrate the versatility of our cassettes, we have selected an endogenous protein of moderate concentration to better understand the limitations associated with intrinsic fluorescence of FP variants, identified a candidate whose function is required for cell survival, and chosen a protein whose C-terminus extends into the cytosol thereby providing environmental conditions adequate for FlAsH-based technology.

Commonly referred to as the essential subunit of the ER translocon in yeast, Sec61 is a polytopic membrane protein that consists of three transmembrane domains and a C-terminus exposed to the cytosol (Deshaies and Schekman, 1987). The protein concentration of Sec61 has been estimated as 24,800 molecules/cell (Ghaemmaghami, et al., 2003) based on tandem affinity purification (Hamilton, et al., 2002; Howson, et al., 2005); maintains a molecular weight of 52.9 kDa; and has been shown to localize and function properly when fused to GFP (Luedeke, et al., 2005). Sec61’s protein concentration is considered moderate compared to other examples of endogenous yeast fusion proteins such as Cdc19 (291,000 molecules/cell) (Sheff and Thorn, 2004), Tdh3 (169,000 molecules/cell) (Sheff and Thorn, 2004), Nup49 (4,760 molecules/cell) (Sheff and Thorn, 2004), Cdc11 (9,280 molecules/cell) (Sheff and Thorn, 2004), and Erg6 (53,000 molecules/cell) (Vorvis, et al., 2008)which have been fused to GFP variants using alternative PCR-based modules; hence, Sec61 is an adequate target when contrasting the utility of fluorescent probes among numerous techniques.

Implementation of GFP and DsRed Variants

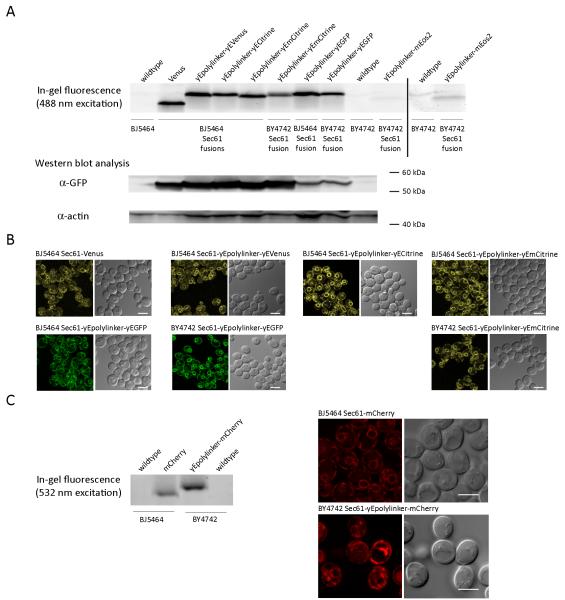

We have determined the viability of each novel tag and fluorescent variant by directing appropriate modules to the Sec61 ORF using homologous recombination. Comparisons of individual strains of Sec61 fusions yield data that can be used to predict appropriate tags for any protein of interest. To evaluate the expression of Sec61 fusion proteins, a facile and direct approach was used for green, yellow, and red fluorescent protein variants. Previously, an in-gel fluorescence technique (Newstead, et al., 2007) examined the intrinsic fluorescence of GFP fused to membrane proteins of S. cerevisiae in a high-throughput manner. We chose to exploit the spectral characteristics of additional FP variants in order to test plausible fusion protein transformants, as compared to parental strains. Our data indicate that in-gel fluorescent methods are an adequate means of assessing endogenous fusion proteins of moderate concentration (Figure 2 A, C). To confirm the expression of desired products, GFP variants were probed using standard Western blot techniques. Protein concentrations were normalized to an established loading control, β-actin, which provides a means of direct comparison among various fusion protein strains (Figure 2 A). Furthermore, live-cell imaging ensured that FP variants did not cause mislocalization. As seen in Figure 2 B and C, all Sec61 fusion proteins were correctly localized to the ER, an organelle that consists of three sub-compartments in yeast (Preuss, et al., 1991): perinuclear ER, cortical ER, and tubular connections, yet forms one continuous structure.

Figure 2. (A) Expression of Sec61 GFP variants and photoswitchable protein fusions.

In-gel fluorescence analysis of GFP variants fused to Sec61 compared to parental strains. Results to the right of the vertical line (i.e. wildtype BY4742 and Sec61-yEpolylinker-mEos2) are shown with linearly increased intensities when compared to protein bands left of the vertical line, in order to visualize the fluorescence of the native (green) species of mEos2. Western blot analysis shows corresponding lanes; protein bands were probed with anti-GFP and compared to total protein load via an appropriate control, anti-β-actin. (B) Live-cell imaging of Sec61 GFP variants. Fluorescence (left) and DIC (right) images of the indicated strains acquired by confocal microscopy, as described in Materials and Methods (Zeiss LSM 5 DUO, 100x/NA 1.46 objective). (C) Implementation of optimal DsRed variant, Sec61-mCherry. In-gel fluorescence shows the desired species excited at 532 nm compared to respective parental strains. Live-cell imaging of Sec61 fusion proteins – fluorescence (left) and DIC (right) - were acquired with improved sensitivity (Zeiss 780 confocal microscope, 100x/NA 1.46) at an excitation of 561 nm. All scale bars are 5 μm.

The success, of any experiment employing FPs, is highly dependent upon fluorescent parameters (e.g. folding efficiencies, quantum yields, and extinction coefficients) of GFP and DsRed variants, instrument sensitivity, and codon-optimized sequences. Therefore, we performed an in-depth analysis of the limitations associated with all green, yellow, and red FPs of designed cassettes. Our results establish a precedent from which members of the yeast community may rely upon during their selection of variants for similar techniques. Attempts to quantify fluorescent intensities of GFP variants, using whole-cell fluorescence techniques, ultimately resulted in significant experimental error. When constitutively expressed from its endogenous promoter, Sec61’s moderate protein concentration was not adequately detected in whole-cell assays; thus, confocal microscopy was employed to assess the suitability of GFP variants when fused to Sec61. To compare the intensities of yellow variants (e.g. Venus, yEVenus, yECitrine, and yEmCitrine) under identical settings, fluorescence was normalized to area, and values were reported as the mean ± SE. A yeast-enhanced polylinker combined with codon-optimized variants are two- to three-fold more intense than Venus, as shown in Table 2. Our results show that yEmCitrine and yECitrine are two-fold brighter than yEVenus and Venus, as previously demonstrated in S. cerevisiae by Sheff and Thorn (2004) and in agreement with fluorescent parameters associated with Venus and Citrine (Griesbeck, et al., 2001; Nagai, et al., 2002). Improved DsRed variants, consisting of Sec61 mCherry fusions, were not adequately detected by time-lapse imaging on a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope equipped with standard photomultiplier tube (PMT) detectors. However, due to overall increased sensitivity of the Zeiss LSM 780, including GaAsP detectors which are two-fold more sensitive than standard PMTs (Zipfel, et al., 2003), Sec61 mCherry recombinant strains were easily visualized by live-cell imaging. The increased sensitivity was invaluable for monitoring multiple fusion proteins simultaneously, especially when evaluating mCherry and Cerulean fusion proteins of moderate concentrations (data not shown).

Combined, we have established that in-gel fluorescence is a facile method to evaluate FP expression prior to confirmation by standard Western blot analysis and genomic PCR. Moreover, live-cell imaging techniques evaluated the correct localization of select fusion proteins and verified the suitability of each probe based on fluorescent parameters such as intensity and photobleaching effects. Interestingly, Sec61 fused to DsRed variants did not possess adequate fluorescence for time-lapse imaging with standard confocal microscopy; thus, we identified limitations associated with the choice of FP. These comprehensive results will allow others to compare, correlate, and determine the appropriate selection of tags for additional proteins of interest.

In Vivo Fluorescent Labeling Achieved with a TetCys Motif

Due to the large size of fluorescent variants (i.e. approximately 27 kDa and 240 residues), in some instances FP fusions may result in mislocalization or decreased functionality of target proteins; therefore, we incorporated a codon-optimized TetCys motif to be used with FlAsH-based technology, in addition to electron microscopy methods that correlate images at various levels of spatial resolution in the absence of gold nanoparticles (Gaietta, et al., 2002). Prior to this study, it has been shown that the biarsenical-tetracysteine system using FlAsH as a fluorophore is an efficient labeling method for β-tubulin (Andresen, et al., 2004), as well as mitochondrial proteins under selective growth conditions in budding yeast (Wurm, et al., 2010). Our results demonstrate the first time a yeast-enhanced TetCys motif has been fused to a protein of the secretory pathway, specifically the ER, of yeast (Figure 3 A). As shown, recombinant Sec61 results in a predominant ER-localized species following 60 min incubation with FlAsH.

Figure 3. (A) Sec61 fused to a tetracysteine motif and labeled with FlAsH.

In vivo labeling of live cells expressing endogenous Sec61 fused to an optimal TetCys motif. Fluorescent (left) and DIC (right) images are a representative sample (N > 50) of FlAsH-based technology for Sec61-tagged proteins following a 60-minute incubation period, as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Optimization and Topology of Sec61-yEFlAsH. To decrease autofluorescence and noise associated with the labeling experiment, cells were grown to early mid-log phase and incubated at varying durations (i.e. 30, 60, and 90 min) of specified reagents. BY4742 Sec61-yEFlAsH (top row) was incubated for 60 minutes. Parental strain (BY4742) was incubated at the same concentration of reagent and all specified durations, then imaged under identical microscopy settings as the recombinant Sec61 FlAsH fusion protein. Representative images of BY4742 are shown for 30 minutes (middle row) and 90 minutes (bottom row). At minimal periods of incubation, non-specificity of the reagent is evident. Sec61 is a polytopic membrane protein consisting of 10 transmembrane domains. The topology of Sec61-yEFlAsH depicts the optimized C-terminal TetCys motif exposed to the cytosol (right, illustration modified from Ng, W. et al. (2007)). All scale bars are 5 μm.

The optimized TetCys motif (i.e. Cys-Cys-Pro-Gly-Cys-Cys; Figure 1D) has a higher affinity and enhanced stability for FlAsH reagents when compared to other characterized motifs (Griffin, et al., 1998). Our data confirm that codon-optimized TetCys motifs and FlAsH-based technology appropriately identify recombinant proteins localized to the ER membrane (Figure 3 A, B (top row)) using commercial reagents and modified protocols for yeast systems. The optimized sequence occurs infrequently in the genome although parental strains BY4742 display evidence of non-specific intracellular labeling (Figure 3 B) reminiscent of phenotypes associated with the vacuole (Ren, et al., 2008) and lipid droplets (Kohlwein, 2010) in yeast. However, our demonstration of successfully labeling recombinant proteins fused to a TetCys motif in vivo will aid in the studies of protein assembly and internalization; distinguish nascent proteins; and evaluate protein trafficking temporally through pulse-chase techniques (Gaietta, et al., 2002). Additionally, correlative microscopy techniques used to evaluate protein localization based on FlAsH tags result in increased specificity when compared to gold-nanoparticles at EM resolution and have revolutionized correlative microscopy techniques providing the ultra-structural resolution necessary to evaluate the effects of protein localization (Gaietta, et al., 2002; Hoffmann, et al., 2005).

Photoswitchable mEos2 Utility – Monitoring Dynamics by Confocal Microscopy and Sub-cellular Localization using Super-Resolution Microscopy

Investigation into dynamic processes of a living cell, particularly the spatial localization of discrete subpopulations of tagged proteins, is accomplished by photoswitchable fluorescent variants such as mEos2. When compared to its predecessors, mEos2 exhibits increased photostability while preserving ~ 10 nm localization precision of tagged proteins as demonstrated by high-resolution PALM techniques (McKinney, et al., 2009). Thus, photoswitchable mEos2 represents a convenient tool to facilitate protein-tracking and localization studies at the sub-organelle level. Our analysis represents the first evaluation of mEos2 in yeast (Figure 4 A) culminating in reproducible experimental conditions leading to the converted species of a photoswitchable variant.

Figure 4. (A) Photoswitchable mEos2 analyzed in S. cerevisiae.

Live cells expressing Sec61-yEpolylinker-mEos2 tagged at the chromosomal locus. A sample of the population was imaged prior to photoconversion at 405 nm (top row), and then imaged again following the switch from a green-to-red species within the region of interest (ROI) indicated by the red circle. Each row consists of four panels: green channel (excitation at 488 nm), red channel (excitation at 561 nm), merged image including both the red and green channel, and the DIC image with corresponding ROI. A subset of cells in the ROI is appropriately converted from green-to-red (bottom row, red channel). It is also important to note that a percentage of the unconverted species of mEos2 appears to fluoresce in the red channel of the microscopy settings (Figure 4 A, top row, second panel). In order to determine that the autofluorescence is specific to an unconverted mEos2 species, we compared BY4742 Sec61-yEpolylinker-yEGFP under identical confocal microscopy settings. (B) In vivo comparison of yEGFP to mEos2. The intensity of the native (green) species of mEos2 is comparative to yEGFP under identical fluorescent parameter settings. Yet, yEGFP does not display any fluorescence in the red (e.g. excitation at 561 nm) channel positioned as the middle panel, with green fluorescence (left) and DIC (right), as shown. Total fluorescence of the yEGFP Sec61 fusion is detected in the green channel, and not the red channel, as expected and desired; whereas in our studies with the photoconvertible variant, low fluorescent levels of the unconverted species in the red channel were detectable. (C) PALM imaging provided high-resolution of Sec61 mEos2 fusion proteins in S. cerevisiae. Endogenous Sec61 fused to mEos2 is localized to the nuclear envelope (arrow) and peripheral ER (arrowhead) in yeast. Photoconversion and subsequent single molecule localization of mEos2 red emission under laser illumination showed localization in agreement with low-resolution (Figure 4 A) results. This data demonstrated the feasibility of using mEos2 as a fusion protein for super-resolution microscopy in yeast. All scale bars are 5 μm.

BY4742 Sec61-yEpolylinker-mEos2 was imaged initially at excitation and emission spectra settings of its native (green) species (Figure 4 A, top row) followed by illumination at 405 nm of a selective region of interest (ROI). The photoconverted (red) species of Sec61-yEpolylinker-mEos2 was then detected (Figure 4 A, bottom row). As indicated by the ROI, conversion of the mEos2 fusion is evident in the subpopulation investigated. Utilizing the photoconversion of mEos2 in yeast to facilitate protein-tracking studies or to analyze newly synthesized proteins (e.g. native versus converted species), a comparison between the intensity of the native (green) species of mEos2 and yEGFP is useful. In molecular cell biology, GFP is ubiquitously used and represents a convenient standard from which to compare the fluorescence of photoswitchable mEos2. From our observations and specific growth conditions associated with the Sec61 mEos2 fusion protein, the normalized fluorescence intensity of the native (green) species (415 ± 30 AU, N = 43) is within an order of magnitude of the yEGFP (1681 ± 55 AU, N = 64), which enables adequate visualization under identical microscopy settings (Figure 4 B). Despite the fact that mEos2 has four-fold less intensity than the yEGFP fluorescence, we can infer that this photoswitchable variant would be an appropriate tag to analyze the dynamics of discrete subpopulations for any protein of moderate to high protein concentrations.

Fusion proteins consisting of mEos2, or its predecessors, in combination with PALM/transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging, result in nanometer spatial resolution; thus, these techniques have the ability to determine the distribution of specified proteins in relation to cellular structures at a significantly higher molecular density than immunolabeled TEM (Betzig, et al., 2006). PALM has revealed the spatial heterogeneity of proteins in organelle subcompartments using photoswitchable variants (Betzig, et al., 2006). Using high-resolution techniques, our investigations have shown that mEos2 is successfully localized by PALM with improved resolution (Figure 4 C). Incorporating fluorescent light microscopy and super-resolution techniques, our results indicate the usefulness of mEos2 to monitor dynamic processes of the cell, and to determine the influence of protein localization and its extent on cell structure, function, and regulation.

To experimentally address the significance of spatial localization of proteins and complexes, high-resolution techniques are essential, providing the appropriate spatiotemporal resolution necessary to confirm the roles of respective targets in cell physiology. In summary, we have described a new series of versatile PCR-based modules for C-terminal tagging of yeast proteins. These plasmids incorporate epitope tags, fluorophores for four-color imaging, FlAsH tag, and photoswitchable fluorescent protein, mEos2. When applicable, tags have been codon-optimized for S. cerevisiae but in most cases are potentially appropriate for any yeast strain, including Candida albicans. A single pair of PCR primers can be used for amplification of all 35 modules, enabling numerous combinations of tags and selection markers. Additionally, reverse primers recommended for previously reported pFA6a-based plasmids (Funakoshi and Hochstrasser, 2009; Janke, et al., 2004; Petracek and Longtine, 2002); Sung and Huh, 2007; Tagwerker et al., 2006; Wach et al., 1997) are compatible with this new series of cassettes, while forward and reverse primers designed for pKT modules (Sheff and Thorn, 2004) are identical. Plasmids including the kanMX and hphMX4 genes are applicable for C-terminal tagging in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Bahler, et al., 1998; Marti, et al., 2003) while kanMX and the zeocin resistance gene can be used in Pichia pastoris (Papakonstantinou, et al., 2009). Our designs can be implemented similarly to a described system for C-terminal epitope switching (Sung, et al., 2008) as well as to target gene disruptions and deletions in yeast. In summary, we envision this series of modules to be an invaluable tool, broadly applicable, to yeast researchers investigating the spatial and temporal progression of proteins. The 35 new plasmids, and details regarding their sequences, are available at the non-profit plasmid repository Addgene (http://www.addgene.org).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Bryant Chhun of Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, LLC and his expertise with super-resolution microscopy; Zachary Britton and Lindsay Schiemdel for assistance in molecular engineering design; as well as Dr. Kurt Thorn, Nikon Imaging Center, Director at the University of California San Francisco and Dr. Loren L. Looger, Janelia Farm Research Campus, Howard Hughes Medical Institute for providing select plasmids through Addgene nonprofit plasmid repository, as identified in Supplemental Table S1. This work was supported by the Addgene DNA Recombinant Technology Award 2010 (CLY, ASR), NIH RO1 GM65507, NIH P20 RR15588 (CLY, DR, ASR), NSF Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship (IGERT) Fellowship NSF-IGERT 0221651 (CLY), and NIH NCRR SIG 1S10 RR027273-01 (DBI Bio-Imaging). This publication was made possible by Grant Number 2 P20 RR016472-10 under the INBRE program and P20RR015588-06 under the COBRE program of the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (CLY, ASR, KC).

References

- Abramoff MD, Magelhaes PJ, Ram SJ. Image Processing with Image J. Biophotonics International. 2004;11:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Adams SR, Campbell RE, Gross LA, Martin BR, Walkup GK, Yao Y, Llopis J, Tsien RY. New biarsenical ligands and tetracysteine motifs for protein labeling in vitro and in vivo: synthesis and biological applications. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:6063–76. doi: 10.1021/ja017687n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando R, Hama H, Yamamoto-Hino M, Mizuno H, Miyawaki A. An optical marker based on the UV-induced green-to-red photoconversion of a fluorescent protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12651–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202320599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen M, Schmitz-Salue R, Jakobs S. Short tetracysteine tags to beta-tubulin demonstrate the significance of small labels for live cell imaging. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:5616–22. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-06-0454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahler J, Wu JQ, Longtine MS, Shah NG, McKenzie A, 3rd, Steever AB, Wach A, Philippsen P, Pringle JR. Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast. 1998;14:943–51. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<943::AID-YEA292>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudin A, Ozier-Kalogeropoulos O, Denouel A, Lacroute F, Cullin C. A simple and efficient method for direct gene deletion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3329–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.14.3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betzig E, Patterson GH, Sougrat R, Lindwasser OW, Olenych S, Bonifacino JS, Davidson MW, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Hess HF. Imaging intracellular fluorescent proteins at nanometer resolution. Science. 2006;313:1642–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1127344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann CB, Davies A, Cost GJ, Caputo E, Li J, Hieter P, Boeke JD. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast. 1998;14:115–32. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19980130)14:2<115::AID-YEA204>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell RE, Tour O, Palmer AE, Steinbach PA, Baird GS, Zacharias DA, Tsien RY. A monomeric red fluorescent protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:7877–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082243699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan J, Niethammer M, Taylor RM, 2nd, Czymmek KJ. The power of correlative microscopy: multi-modal, multi-scale, multi-dimensional. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011;21:686–93. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chudakov DM, Verkhusha VV, Staroverov DB, Souslova EA, Lukyanov S, Lukyanov KA. Photoswitchable cyan fluorescent protein for protein tracking. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1435–9. doi: 10.1038/nbt1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormack BP, Bertram G, Egerton M, Gow NA, Falkow S, Brown AJ. Yeast-enhanced green fluorescent protein (yEGFP)a reporter of gene expression in Candida albicans. Microbiology. 1997;143(Pt 2):303–11. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-2-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormack BP, Valdivia RH, Falkow S. FACS-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) Gene. 1996;173:33–8. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshaies RJ, Schekman R. A yeast mutant defective at an early stage in import of secretory protein precursors into the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:633–45. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.2.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazer LN, O’Keefe RT. A new series of yeast shuttle vectors for the recovery and identification of multiple plasmids from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2007;24:777–89. doi: 10.1002/yea.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funakoshi M, Hochstrasser M. Small epitope-linker modules for PCR-based C-terminal tagging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2009;26:185–92. doi: 10.1002/yea.1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaietta G, Deerinck TJ, Adams SR, Bouwer J, Tour O, Laird DW, Sosinsky GE, Tsien RY, Ellisman MH. Multicolor and electron microscopic imaging of connexin trafficking. Science. 2002;296:503–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1068793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher S, Winston SE, Fuller SA, Hurrell JG. Immunoblotting and immunodetection. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2004 doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb1008s66. Chapter 10, Unit 10 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerami-Nejad M, Berman J, Gale CA. Cassettes for PCR-mediated construction of green, yellow, and cyan fluorescent protein fusions in Candida albicans. Yeast. 2001;18:859–64. doi: 10.1002/yea.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerami-Nejad M, Dulmage K, Berman J. Additional cassettes for epitope and fluorescent fusion proteins in Candida albicans. Yeast. 2009;26:399–406. doi: 10.1002/yea.1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaemmaghami S, Huh WK, Bower K, Howson RW, Belle A, Dephoure N, O’Shea EK, Weissman JS. Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature. 2003;425:737–41. doi: 10.1038/nature02046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz RD, Woods RA. Transformation of yeast by lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier DNA/polyethylene glycol method. Methods Enzymol. 2002;350:87–96. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)50957-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffeau A, Barrell BG, Bussey H, Davis RW, Dujon B, Feldmann H, Galibert F, Hoheisel JD, Jacq C, Johnston M, Louis EJ, Mewes HW, Murakami Y, Philippsen P, Tettelin H, Oliver SG. Life with 6000 genes. Science. 1996;274:546, 563–7. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein AL, McCusker JH. Three new dominant drug resistance cassettes for gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1999;15:1541–53. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199910)15:14<1541::AID-YEA476>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabenbauer M, Geerts WJ, Fernadez-Rodriguez J, Hoenger A, Koster AJ, Nilsson T. Correlative microscopy and electron tomography of GFP through photooxidation. Nat Methods. 2005;2:857–62. doi: 10.1038/nmeth806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesbeck O, Baird GS, Campbell RE, Zacharias DA, Tsien RY. Reducing the environmental sensitivity of yellow fluorescent protein. Mechanism and applications. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29188–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102815200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin BA, Adams SR, Tsien RY. Specific covalent labeling of recombinant protein molecules inside live cells. Science. 1998;281:269–72. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5374.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurskaya NG, Verkhusha VV, Shcheglov AS, Staroverov DB, Chepurnykh TV, Fradkov AF, Lukyanov S, Lukyanov KA. Engineering of a monomeric green-to-red photoactivatable fluorescent protein induced by blue light. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:461–5. doi: 10.1038/nbt1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson MG. Nonlinear structured-illumination microscopy: wide-field fluorescence imaging with theoretically unlimited resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13081–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406877102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hailey DW, Davis TN, Muller EG. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer using color variants of green fluorescent protein. Methods Enzymol. 2002;351:34–49. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)51840-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton SR, O’Donnell JB, Jr., Hammet A, Stapleton D, Habinowski SA, Means AR, Kemp BE, Witters LA. AMP-activated protein kinase kinase: detection with recombinant AMPK alpha1 subunit. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;293:892–8. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00312-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikal AA, Hess ST, Baird GS, Tsien RY, Webb WW. Molecular spectroscopy and dynamics of intrinsically fluorescent proteins: coral red (dsRed) and yellow (Citrine) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:11996–2001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.22.11996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess ST, Girirajan TP, Mason MD. Ultra-high resolution imaging by fluorescence photoactivation localization microscopy. Biophys J. 2006;91:4258–72. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.091116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess ST, Gould TJ, Gudheti MV, Maas SA, Mills KD, Zimmerberg J. Dynamic clustered distribution of hemagglutinin resolved at 40 nm in living cell membranes discriminates between raft theories. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17370–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708066104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann C, Gaietta G, Bunemann M, Adams SR, Oberdorff-Maass S, Behr B, Vilardaga JP, Tsien RY, Ellisman MH, Lohse MJ. A FlAsH-based FRET approach to determine G protein-coupled receptor activation in living cells. Nat Methods. 2005;2:171–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howson R, Huh WK, Ghaemmaghami S, Falvo JV, Bower K, Belle A, Dephoure N, Wykoff DD, Weissman JS, O’Shea EK. Construction, verification and experimental use of two epitope-tagged collections of budding yeast strains. Comp Funct Genomics. 2005;6:2–16. doi: 10.1002/cfg.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh WK, Falvo JV, Gerke LC, Carroll AS, Howson RW, Weissman JS, O’Shea EK. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature. 2003;425:686–91. doi: 10.1038/nature02026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janke C, Magiera MM, Rathfelder N, Taxis C, Reber S, Maekawa H, Moreno-Borchart A, Doenges G, Schwob E, Schiebel E, Knop M. A versatile toolbox for PCR-based tagging of yeast genes: new fluorescent proteins, more markers and promoter substitution cassettes. Yeast. 2004;21:947–62. doi: 10.1002/yea.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EW. Tackling the protease problem in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:428–53. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94034-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knop M, Siegers K, Pereira G, Zachariae W, Winsor B, Nasmyth K, Schiebel E. Epitope tagging of yeast genes using a PCR-based strategy: more tags and improved practical routines. Yeast. 1999;15:963–72. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199907)15:10B<963::AID-YEA399>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlwein SD. Triacylglycerol homeostasis: insights from yeast. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:15663–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.118356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippincott-Schwartz J, Patterson GH. Development and use of fluorescent protein markers in living cells. Science. 2003;300:87–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1082520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippincott-Schwartz J, Patterson GH. Photoactivatable fluorescent proteins for diffraction-limited and super-resolution imaging. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:555–65. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine MS, McKenzie A, 3rd, Demarini DJ, Shah NG, Wach A, Brachat A, Philippsen P, Pringle JR. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–61. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luedeke C, Frei SB, Sbalzarini I, Schwarz H, Spang A, Barral Y. Septin-dependent compartmentalization of the endoplasmic reticulum during yeast polarized growth. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:897–908. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukyanov KA, Chudakov DM, Lukyanov S, Verkhusha VV. Innovation: Photoactivatable fluorescent proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:885–91. doi: 10.1038/nrm1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinska K, Malinsky J, Opekarova M, Tanner W. Distribution of Can1p into stable domains reflects lateral protein segregation within the plasma membrane of living S. cerevisiae cells. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:6031–41. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti TM, Kunz C, Fleck O. Repair of damaged and mismatched DNA by the XPC homologues Rhp41 and Rhp42 of fission yeast. Genetics. 2003;164:457–67. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.2.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurel D, Banala S, Laroche T, Johnsson K. Photoactivatable and photoconvertible fluorescent probes for protein labeling. ACS Chem Biol. 2010;5:507–16. doi: 10.1021/cb1000229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mc Intyre J, Muller EG, Weitzer S, Snydsman BE, Davis TN, Uhlmann F. In vivo analysis of cohesin architecture using FRET in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 2007;26:3783–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElver J, Weber S. Flag N-terminal epitope overexpression of bacterial alkaline phophatase and Flag C-terminal epitope tagging by PCR one-step integratin. Yeast. 1992;8:S627. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney SA, Murphy CS, Hazelwood KL, Davidson MW, Looger LL. A bright and photostable photoconvertible fluorescent protein. Nat Methods. 2009;6:131–3. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melloy P, Shen S, White E, McIntosh JR, Rose MD. Nuclear fusion during yeast mating occurs by a three-step pathway. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:659–70. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200706151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moqtaderi Z, Struhl K. Expanding the repertoire of plasmids for PCR-mediated epitope tagging in yeast. Yeast. 2008;25:287–92. doi: 10.1002/yea.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller EG, Snydsman BE, Novik I, Hailey DW, Gestaut DR, Niemann CA, O’Toole ET, Giddings TH, Jr., Sundin BA, Davis TN. The organization of the core proteins of the yeast spindle pole body. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:3341–52. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-03-0214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai T, Ibata K, Park ES, Kubota M, Mikoshiba K, Miyawaki A. A variant of yellow fluorescent protein with fast and efficient maturation for cell-biological applications. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:87–90. doi: 10.1038/nbt0102-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Gojobori T, Ikemura T. Codon usage tabulated from international DNA sequence databases: status for the year 2000. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:292. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newstead S, Kim H, von Heijne G, Iwata S, Drew D. High-throughput fluorescent-based optimization of eukaryotic membrane protein overexpression and purification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13936–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704546104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng W, Sergeyenko T, Zeng N, Brown JD, Romisch K. Characterization of the proteasome interaction with the Sec61 channel in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:682–91. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nienhaus GU, Nienhaus K, Holzle A, Ivanchenko S, Renzi F, Oswald F, Wolff M, Schmitt F, Rocker C, Vallone B, Weidemann W, Heilker R, Nar H, Wiedenmann J. Photoconvertible fluorescent protein EosFP: biophysical properties and cell biology applications. Photochem Photobiol. 2006;82:351–8. doi: 10.1562/2005-05-19-RA-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papakonstantinou T, Harris S, Hearn MT. Expression of GFP using Pichia pastoris vectors with zeocin or G-418 sulphate as the primary selectable marker. Yeast. 2009;26:311–21. doi: 10.1002/yea.1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GH, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Selective photolabeling of proteins using photoactivatable GFP. Methods. 2004;32:445–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petracek ME, Longtine MS. PCR-based engineering of yeast genome. Methods Enzymol. 2002;350:445–69. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)50978-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preuss D, Mulholland J, Kaiser CA, Orlean P, Albright C, Rose MD, Robbins PW, Botstein D. Structure of the yeast endoplasmic reticulum: localization of ER proteins using immunofluorescence and immunoelectron microscopy. Yeast. 1991;7:891–911. doi: 10.1002/yea.320070902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu W, Neo SP, Yu X, Cai M. A novel septin-associated protein, Syp1p, is required for normal cell cycle-dependent septin cytoskeleton dynamics in yeast. Genetics. 2008;180:1445–57. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.091900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raicu V, Jansma DB, Miller RJ, Friesen JD. Protein interaction quantified in vivo by spectrally resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Biochem J. 2005;385:265–77. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasband WS. Image J. U.S. National Institutes of Health: City; 1997-2008. http∷//rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/ [Google Scholar]

- Reinke CA, Kozik P, Glick BS. Golgi inheritance in small buds of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is linked to endoplasmic reticulum inheritance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:18018–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408256102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J, Pashkova N, Winistorfer S, Piper RC. DOA1/UFD3 plays a role in sorting ubiquitinated membrane proteins into multivesicular bodies. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21599–611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802982200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo MA, Springer GH, Granada B, Piston DW. An improved cyan fluorescent protein variant useful for FRET. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:445–9. doi: 10.1038/nbt945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothblatt J, Schekman R. A hitchhiker’s guide to analysis of the secretory pathway in yeast. Methods Cell Biol. 1989;32:3–36. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61165-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein R. Targeting, disruption, replacement, and allele rescue: integrative DNA transformation in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:281–301. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabourin M, Tuzon CT, Fisher TS, Zakian VA. A flexible protein linker improves the function of epitope-tagged proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2007;24:39–45. doi: 10.1002/yea.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaub Y, Dunkler A, Walther A, Wendland J. New pFA-cassettes for PCR-based gene manipulation in Candida albicans. J Basic Microbiol. 2006;46:416–29. doi: 10.1002/jobm.200510133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schermelleh L, Carlton PM, Haase S, Shao L, Winoto L, Kner P, Burke B, Cardoso MC, Agard DA, Gustafsson MG, Leonhardt H, Sedat JW. Subdiffraction multicolor imaging of the nuclear periphery with 3D structured illumination microscopy. Science. 2008;320:1332–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1156947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman CE, Struhl K, Sheen J, Jessen T. Introduction of plasmid DNA into cells. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2001 doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb0108s37. Chapter 1, Unit1 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner NC, Campbell RE, Steinbach PA, Giepmans BN, Palmer AE, Tsien RY. Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1567–72. doi: 10.1038/nbt1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner NC, Steinbach PA, Tsien RY. A guide to choosing fluorescent proteins. Nat Methods. 2005;2:905–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheff MA, Thorn KS. Optimized cassettes for fluorescent protein tagging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2004;21:661–70. doi: 10.1002/yea.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman F. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 2002;350:3–41. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)50954-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski RS, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprouse RO, Karpova TS, Mueller F, Dasgupta A, McNally JG, Auble DT. Regulation of TATA-binding protein dynamics in living yeast cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13304–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801901105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung MK, Ha CW, Huh WK. A vector system for efficient and economical switching of C-terminal epitope tags in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2008;25:301–11. doi: 10.1002/yea.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski KM, Binns D, Bartz R, Grishin NV, Li WP, Agarwal AK, Garg A, Anderson RG, Goodman JM. The lipodystrophy protein seipin is found at endoplasmic reticulum lipid droplet junctions and is important for droplet morphology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20890–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704154104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda Y, Nakano A. In vitro formation of a novel type of membrane vesicles containing Dpm1p: putative transport vesicles for lipid droplets in budding yeast. J Biochem. 2008;143:803–11. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvn034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorvis C, Markus SM, Lee WL. Photoactivatable GFP tagging cassettes for protein-tracking studies in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2008;25:651–9. doi: 10.1002/yea.1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wach A, Brachat A, Alberti-Segui C, Rebischung C, Philippsen P. Heterologous HIS3 marker and GFP reporter modules for PCR-targeting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1997;13:1065–75. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19970915)13:11<1065::AID-YEA159>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wach A, Brachat A, Pohlmann R, Philippsen P. New heterologous modules for classical or PCR-based gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1994;10:1793–808. doi: 10.1002/yea.320101310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]