Abstract

In the dynamic nuclear polarization process, microwave irradiation facilitates exchange of polarization from a radical’s unpaired electron to nuclear spins at cryogenic temperatures, increasing polarization by >10000. Doping samples with Gd3+ ions further increases the achievable solid-state polarization. However, upon dissolution, paramagnetic lanthanide metals can be potent relaxation agents, decreasing liquid-state polarization. Here, the effects of lanthanide metals on the solid and liquid-state magnetic properties of [1-13C]pyruvate are studied. The results show that in addition to gadolinium, holmium not only increases the achievable polarization but also the rate of polarization. Liquid-state relaxation studies found that unlike gadolinium, holmium minimally affects T1. Additionally, results reveal that linear contrast agents dissociate in pyruvic acid, greatly reducing liquid-state T1. While macrocyclic agents do not readily dissociate, they yield lower solid-state polarization. Results indicate that polarization with free lanthanides and subsequent chelation during dissolution produces the highest polarization enhancement while minimizing liquid-state relaxation.

Keywords: DNP, polarization, pyruvate

INTRODUCTION

Magnetic resonance is a powerful imaging modality that suffers from low sensitivity, due in part to the small energy difference between the spin-states of non spin-zero nuclei. However, the role of metabolically active compounds such as [1-13C]pyruvate in clinical MRI has been significantly increased by the development of polarization enhancement methods (1,2), including dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) that enhance the measureable signal of polarized 13C-labeled compounds by four orders of magnitude. These metabolic contrast agents have made it possible to image cell metabolism in a wide range of diseases in-vivo, with the potential to detect cancer earlier in its progression and evaluate response to therapy more directly (3–5).

When spin ½ nuclei are placed into a magnetic field (Bo), the spins can either align parallel (n+) or anti-parallel (n−) to the main magnetic field. The thermal equilibrium polarization, or fraction of spins aligned parallel to Bo, is governed by the Boltzmann distribution:

| (1) |

The polarization of water protons at clinical field strengths (1.5–3.0 T) and temperatures (~37°C) is on the order of 10−4 %. While proton imaging is able to overcome this low level of polarization due to the high concentration of water in-vivo, imaging of other biologically relevant nuclei is typically limited to long scan times requiring multiple signal averages due to their low endogenous concentration and lower gyromagnetic ratio (γ). DNP can increase the polarization greater than that dictated by the Boltzmann equilibrium described by Eq. 1, enabling imaging of non-proton nuclei with sub-second temporal resolution.

Dynamic nuclear polarization is a process that can increase the spin population difference between spin states from 10−4 % up to 20 % (6). Typically, samples are placed into a 1.4K helium bath at 3.35T and are irradiated with gigahertz microwaves that facilitate the transfer of polarization from an unpaired electron to nuclei in the sample. Upon dissolution, the nuclear spins equilibrate to the Boltzmann distribution at a rate determined by the characteristic spin-lattice relaxation time, T1

Paramagnetic compounds, such as gadolinium (Gd) based contrast agents, are typically used to shorten liquid-state proton relaxation times, but they can also be used to shorten the relaxation times of any non spin-zero nuclei. Recent work (7–10) has shown that the solid-state polarization obtainable with DNP can be substantially enhanced by the addition of millimolar quantities of GdCl3 or Gd based contrast agents into free pyruvic acid, which can readily form a well-mixed glass upon cooling following insertion of the sample into the polarizer. However, at room temperature and in solution, the same Gd3+ becomes a very efficient relaxation agent, due in part to its slow electronic relaxation rate and 7 unpaired electrons (11). Due to the high relaxivity and toxicity of free Gd3+, only chelated compounds have been previously used to enhance polarization for in-vivo experiments.

While Gd3+ can enhance the solid-state polarization, upon dissolution it also reduces the liquid-state T1 of [1-13C]pyruvate. Extending on a preliminary study (12), we further investigate these two competing factors to optimize and report the effects of unchelated lanthanide metal ions on the solid-state polarization and buildup time of [1-13C]pyruvate, as well as the liquid-state T1 (henceforth referred to as T1,(aq)). In addition, we show that the achievable solid-state polarization is also significantly enhanced by holmium (Ho3+), but not other lanthanides. Furthermore, we show that the use of DTPA during the dissolution process drastically reduces the liquid-state relaxivity (r1,(aq)) of Gd on [1-13C]pyruvate. We attribute this to rapid DTPA chelation of lanthanide metals in the liquid-state, increasing the lanthanide-carbon distance due to electrostatic repulsion and minimizing inner-sphere relaxation due to steric hindrance. Finally, we show that linear contrast agents dissociate in free pyruvic acid, providing a large solid-state enhancement but significantly shortening T1,aq. While macrocyclic agents do not readily dissociate, they provide a lower solid-state enhancement than unchelated Gd3+.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Lanthanide chloride hydrates (LnCl3·xH2O, x = 6 or 7; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) were mixed with the trityl radical OX63 (GE Healthcare) and pyruvic acid (100% [1-13C] and natural abundance; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) to yield solutions with a concentration of 15mM OX63, 12M pyruvic acid (50% 1-13C) and 0.5mM Ln3+.

For each experiment, 30μL aliquots were placed into a 3.35T polarizer (HyperSense®, Tubney Woods, Abingdon, Oxfordshire, UK) and cooled to 1.4K. Prior to polarization, a microwave sweep over the available frequency range of the microwave source (93.690 GHz – 94.296 GHz) was performed for each sample to ensure irradiation at the frequency of maximum positive enhancement (~94 GHz). Samples were subsequently irradiated for one hour, following which solid-state nuclear relaxation times (T1,s) were measured by stopping the microwave irradiation and acquiring spectra with a repetition time ranging from 100s to 600s. The flip angle was independently calibrated by a train of 20 RF pulses in rapid succession using a TR of 1s and neglecting contributions from T1 decay over the short time scale of the experiment. RF decay of the signal was accounted for using S(n) = S(n)/cosn−1 (θ), after which the signal curve was fit to a monoexponential function to determine T1,s.

With an empty f-shell, diamagnetic lanthanum acted as a control for comparison with the enhancement from the other paramagnetic lanthanide metals. Pyruvate doped with Gd3+, which was previously reported to enhance the solid-state polarization (7–10), was used for comparison as a positive control. For each lanthanide studied, the fractional solid-state enhancement was calculated as the mean of the solid-state amplitude normalized to the average solid-state amplitude of pyruvate doped with lanthanum.

Additional pyruvate samples doped with 1.5mM and 3.0mM unchelated Gd or Ho were polarized at their frequency of maximum enhancement. Polarization buildup during the DNP process is characterized by a buildup time τ and an amplitude A, represented as P(t) =A(1 − exp(− t/τ)). Analogous to T1 recovery, the buildup curve is monoexponential while the solid-state polarization P(t) is proportional to the amplitude.

To test the effect of chelation on the solid-state polarization, two commercially available Gd based contrast agents (Bayer-Schering, USA) were studied. A linear chelate (Magnevist, Gd-DTPA) or a macrocyclic chelate (Gadovist, Gd BT-DO3A) were added to provide solutions of 15mM OX63, 12M pyruvic acid (50% 1-13C) and 0.5mM contrast agent. Sample preparation and subsequent measurements were identical to experiments with unchelated lanthanides.

For liquid-state measurements, samples were rapidly dissoluted with a 4mL super-heated solution containing 106mM NaOH, 80mM Tris buffer and either 0.43mM EDTA or 0.28mM DTPA (Sigma-Aldrich) to yield solutions with pH = 7.7 ± 0.2 and a [1-13C]pyruvate concentration of 53mM. The relaxivity of Gd and Ho chelated to these two ligands was calculated from the measured T1,(aq) of pyruvate, where it was assumed that chelation is rapid. T1,(aq) was measured via spectroscopy on a Varian 4.7T (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA, USA) scanner at 25°C with varying repetition time to separate the effects of RF and T1 decay. Statistical significance was assessed with a Wilcoxon ranksum test implemented in Matlab (R2009b, MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA).

RESULTS

SOLID-STATE POLARIZATION

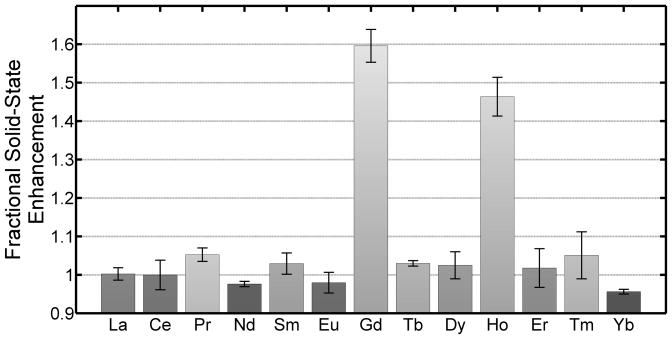

Figure 1 shows the solid-state enhancement factors for the lanthanide series. In addition to Gd, Ho also significantly increases the solid-state polarization at a concentration of 0.5mM (p < 0.05). The diamagnetic lanthanum control and the remaining paramagnetic lanthanides had an insignificant effect on the solid-state polarization enhancement at this concentration.

Figure 1.

Fractional solid-state enhancement for [1-13C]pyruvate in the presence of 0.5mM lanthanide. The remaining paramagnetic lanthanide, promethium, was not studied since no stable isotope exists. Only Gd and Ho significantly (p < 0.05) increased the solid-state polarization of [1-13C]pyruvate at this concentration.

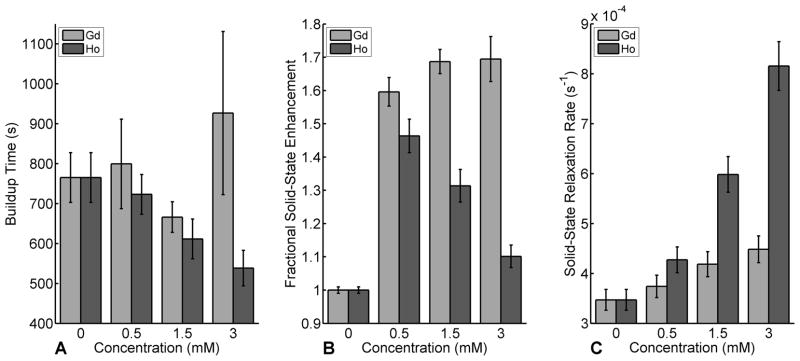

The effects of Gd and Ho doped in pyruvate at higher concentrations were studied and shown to produce differential effects. While Gd does not significantly alter the buildup time τ (Fig. 2A), it does produce an asymptotic increase in solid-state polarization. By comparison, pyruvate doped with Ho behaves very differently. As the concentration of Ho increases, both the amplitude and buildup time significantly decrease (p < 0.05). At a concentration of 3.0mM Ho, the buildup time of pyruvate decreased by 30% while the solid-state amplitude increased by 8%.

Figure 2.

Buildup time (A), fractional solid-state enhancement (B) and solid-state relaxation rate (C) 1/T1,s for [1-13C]pyruvate in the presence of Ho or Gd with 15mM OX63 at 1.4K and 3.35T. Error bars show the standard deviation of the mean for the different concentrations studied (n ≥ 3). At 3mM Ho, the buildup time has decreased by 30% while the solid-state amplitude has still increased by 8%. The significantly larger Ho relaxivity (15.7 vs. 3.3 × 10−4 mM−1 s−1) results in a shorter buildup time, accounting for the lower achievable polarization at high Ho concentrations.

The solid-state enhancement for pyruvate doped with Gd contrast agents were observed to depend on the ligand used for chelation. In the presence of 0.5mM Magnevist, the solid-state enhancement was nearly identical to that of free Gd3+ (51 ± 3 and 55 ± 4%, respectively). In contrast, samples doped with 0.5mM Gadovist yielded a significantly lower enhancement (40 ± 3%).

Solid-state nuclear T1 times were measured for pyruvate over the range of concentrations of unchelated Gd or Ho (Fig. 2C). A linear relationship between lanthanide concentration and nuclear relaxation rate was observed for both lanthanides. The measured relaxivity of Ho in the solid-state (1.5 ± 0.09 × 10−3 mM−1s−1) was nearly five times greater than that of Gd (0.33 ± 0.02 × 10−3 mM−1s−1).

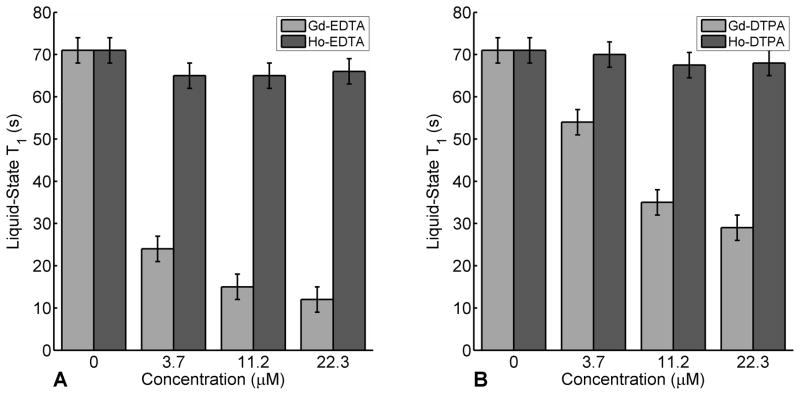

LIQUID-STATE DISSOLUTIONS

Figure 3 shows the [1-13C]pyruvate liquid-state T1 for dissolutions with EDTA or DTPA in the presence of Gd or Ho. All concentrations of Gd studied produce a significant decrease in T1,(aq) relaxation times. This is in contrast with Ho, where minimal changes in T1,(aq) were observed. The signal decay of [1-13C]pyruvate in the presence of either lanthanide was observed to be monoexponential. Relaxivities were measured for both lanthanides, with Gd-EDTA being nearly two orders of magnitude larger (4.5 ± 0.2 mM−1s−1, as compared to 0.03 ± 0.02 mM−1s−1 for Ho-EDTA). Compared to dissolution with EDTA, dissolution with DTPA effectively mitigates the paramagnetic effects of Gd, decreasing the relaxivity of Gd by a factor of 5 (yielding a value of 0.92 ± 0.3 mM−1 s−1). Dissolution with DTPA does not significantly decrease the relaxivity of Ho. Nevertheless, dissolution with Ho minimizes T1 losses in the liquid-state regardless of its chelation.

Figure 3.

13C T1 relaxation times for [1-13C]pyruvate at 25°C and 4.7T in the presence of Ho or Gd chelated to EDTA (A) or DTPA (B) following the dissolution process. For concentrations studied, the [1-13C]pyruvate liquid-state T1 is greater with Ho. Furthermore, dissolution with DTPA mitigates the paramagnetic relaxation effects of Gd.

On dissolution with EDTA, samples doped with Gd contrast agents displayed significantly different T1,(aq) relaxation times. Pyruvate mixed with 0.5mM Magnevist was measured to have a T1,(aq) of 29 ± 0.2s, in good agreement with samples doped with 0.5mM Gd3+. In contrast, samples doped with 0.5mM Gadovist were measured to have T1,(aq) relaxation times of 58 ± 5s, significantly greater than T1,(aq) in the presence of Magnevist.

DISCUSSION

SOLID-STATE POLARIZATION

Using an unmodified commercial DNP system, comparison of all the lanthanides show that only Gd and Ho significantly affect solid-state enhancement and buildup time. While both increase solid-state polarization, the effects of these two lanthanides show significant differences depending on their concentration. Higher concentrations of Gd lead to an asymptotic increase in solid-state enhancement, whereas higher concentrations of Ho lead to a decrease in the solid-state enhancement and buildup time of [1-13C]pyruvate. These differences in behavior can be explained in part by the factor of 4 higher solid-state relaxivity of Ho (Figure 2C).

Other lanthanides, such as dysprosium and erbium, have similar magnetic moments and electronic relaxation times as holmium (Table 1) yet do not significantly effect the polarization of pyruvate. However, these values were not measured at the operating temperature and field-strength of the polarizer. Low temperatures are known to alter the molecular conformation and electronic spin-states (13), and electronic relaxation times depend on both field-strength and ligand (14). Therefore, while the values listed in Table 1 provide a framework for predicting liquid-state relaxation, they are inadequate for predicting polarization enhancement at these low temperatures.

Table 1.

Properties of paramagnetic lanthanides used in this study. Magnetic moments are in units of Bohr magnetons.

It is speculated that the interaction between the lanthanide metal and the trityl radical is responsible for the polarization enhancement, shortening the radical’s electronic relaxation time and leading to an increase in obtainable polarization. If true, then this mechanism is likely to be of general application to enable enhanced polarization for 13C labeled molecules or other nuclei.

LIQUID-STATE DISSOLUTIONS

Since only Gd and Ho significantly affected the polarization enhancement of pyruvate (Fig. 1), liquid-state relaxivities were measured for these two lanthanides. The monoexponential signal decay for pyruvate indicates that chelation with EDTA and DTPA during the dissolution process occurred rapidly for both metal ions. As expected, the liquid-state relaxivity of Gd is more than an order of magnitude higher than that of Ho (4.5 vs. 0.03 mM−1 s−1, Fig. 3A). Furthermore, dissolution and subsequent chelation with DTPA significantly decreased the relaxivity of Gd on [1-13C]pyruvate, mitigating the paramagnetic effects of Gd on the liquid-state polarization. The discrepancy in liquid-state relaxivities between Gd and Ho may be accounted for by the dramatically higher electronic spin relaxation rate of Ho (Table 1). This difference in relaxivities is likely to hold for other polarizable carboxylic acids, as relaxivity with these chelates is largely mediated by outer-sphere effects and therefore by the distance of closest approach. For compounds with shorter 13C relaxation times, polarization enhancement using Ho may be preferred over Gd due to the lower liquid-state relaxivity.

In all cases, the relaxivity of both Gd and Ho are mitigated with increasing amounts of DTPA (Fig. 4). Whereas DTPA is an octadentate ligand, EDTA is only hexadentate. Since Gd3+ and other lanthanides prefer 8–9 coordinate structures (15), chelation with EDTA occupies only six of these coordination sites, increasing the likelihood of inner-sphere relaxation effects and therefore the measured relaxivity. As has been shown with Gd-DO3A, heptadentate contrast agents with an inner-sphere relaxation mechanism can greatly enhance the relaxation rate of carbon nuclei (16,17). Furthermore, charge of the chelate plays a role in relaxivity, as increasing negative charge will increase the distance of closest approach between the two anionic species, also leading to a lower relaxivity (18,19). These two factors, in combination, help to explain the higher relaxivity of lanthanides chelated to EDTA.

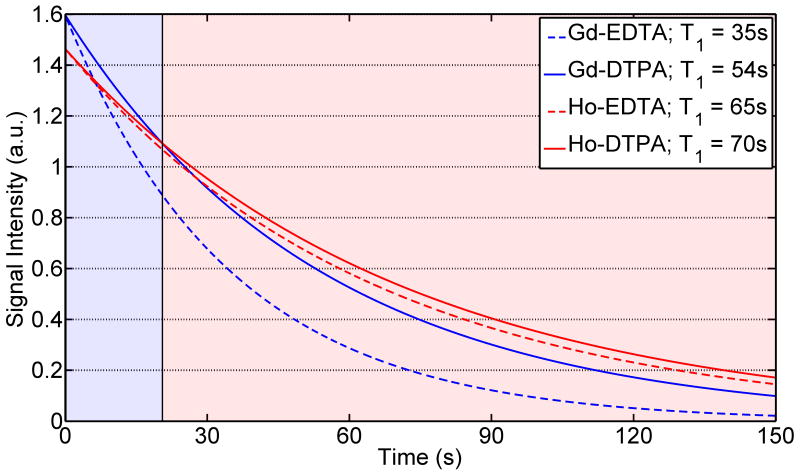

Figure 4.

Simulated liquid-state decay curves for 53mM [1-13C]pyruvate in the presence of 3.7μM lanthanide. Initial signal intensity and liquid-state T1 were obtained from Figs. 1 & 3. The shaded regions correspond to the time where pyruvate in the presence of Gd (blue) or Ho (red) has higher signal intensities. For comparison, the T1 of 53mM [1-13C]pyruvate in the absence of lanthanides was measured to be 71s.

These results show that the optimal lanthanide to use for polarization enhancement depends on a range of factors, most importantly the T1,(aq). Therefore, despite the fact that higher concentrations of Gd would yield a greater solid-state polarization enhancement, the concomitant reduction in T1,(aq) would obviate any utilizable signal gains. At decay times between 15 and 30s, which correspond to the beginning of injection for many applications, the use of Ho can increase solid-state polarization while mitigating liquid-state decay compared to Gd (Figure 4). Once injected, both solutions would give similar in-vivo T1 relaxation times due to dilution in the vascular system. This increased T1 relaxation for Gd could potentially be overcome with a rapid injection system (20) or dissolution with other ligands that are more anionic, or possess no sites for inner-sphere binding (such as TTHA (21) or DOTP (22)).

POLARIZATION WITH CONTRAST AGENTS

The acidity of pure pyruvic acid (pKa = 2.4) (23) promotes dechelation of the metal-ligand complex (24). If dechelation were to occur, the solid-state enhancement should be similar for samples doped with free Gd3+ or a Gd chelate. This was found for Magnevist (Gd-DTPA) but not Gadovist (Gd BT-DO3A), underlining the increased stability of the macrocyclic ligand and providing insight into the polarization enhancement mechanism. The reduced solid-state enhancement of Gadovist (40 ± 3% vs. 55 ± 4% for free Gd3+) suggests the chelate unfavorably restricts the interaction between the metal and the constituents of the solid-state matrix. The liquid-state observations corroborate these results, as the T1,(aq) for samples dissoluted with EDTA and doped with Magnevist was significantly shorter than T1,(aq) for samples doped with Gadovist. These results can be understood by the increased thermodynamic stability of the ligand used in Gadovist (BT-DO3A), which is 4 orders of magnitude greater than that of DTPA (24).

For the more stable macrocyclic ligand, the fractional solid-state enhancement for [1-13C]pyruvate is significantly decreased. As an alternative, polarization with unchelated Gd3+ and dissolution with a chelate such as DTPA provides the greatest solid-state enhancement while minimizing T1,(aq) losses.

CONCLUSION

Of the lanthanides investigated, only Ho and Gd significantly enhanced the solid-state polarization of [1-13C]pyruvate. Depending on the concentration, Ho may be used to increase the solid-state polarization by a factor of 1.5 or decrease the buildup time by 30%. While Gd is more effective than Ho at enhancing the solid-state polarization, it is a more efficient relaxation agent in the liquid-state, potentially negating its beneficial effects. Whereas polarization enhancement has commonly been performed with macrocyclic Gd contrast agents, a greater enhancement can be achieved by adding free Gd3+ to the sample and chelating the metal during the dissolution process.

For carbon-13 labeled compounds with long solid-state buildup times, short liquid-state T1, or in situations where the solution requires filtration or additional preparation prior to application, Ho provides a potential advantage to polarization enhancement with Gd. Furthermore, many other compounds that have been hyperpolarized exhibit shorter liquid-state T1 times than pyruvate (5,25–27), limiting the usefulness of Gd. Under these circumstances, the use of Ho is preferred.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Will Mander (Oxford Instruments) for helpful discussions on measuring solid-state T1. This work was supported by GE Healthcare and NIH-NIA grant number P50-AG033514.

References

- 1.Rowland I, Peterson E, Gordon J, Fain S. Hyperpolarized 13C MR. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2010;11:709–719. doi: 10.2174/138920110792246636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Månsson S, Johansson E, Magnusson P, Chai C-M, Hansson G, Petersson J, Ståhlberg F, Golman K. 13C imaging—a new diagnostic platform. Eur Radiol. 2006;16(1):57–67. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-2806-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albers MJ, Bok R, Chen AP, Cunningham CH, Zierhut ML, Zhang VY, Kohler SJ, Tropp J, Hurd RE, Yen Y-F, Nelson SJ, Vigneron DB, Kurhanewicz J. Hyperpolarized 13C Lactate, Pyruvate, and Alanine: Noninvasive Biomarkers for Prostate Cancer Detection and Grading. Cancer Res. 2008;68(20):8607–8615. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darpolor MM, Yen Y-F, Chua M-S, Xing L, Clarke-Katzenberg RH, Shi W, Mayer D, Josan S, Hurd RE, Pfefferbaum A, Senadheera L, So S, Hofmann LV, Glazer GM, Spielman DM. In vivo MRSI of hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate metabolism in rat hepatocellular carcinoma. NMR Biomed. 2010:506–513. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Witney TH, Kettunen MI, Hu De, Gallagher FA, Bohndiek SE, Napolitano R, Brindle KM. Detecting treatment response in a model of human breast adenocarcinoma using hyperpolarised [1-13C] pyruvate and [1,4-13C2] fumarate. Br J Cancer. 2010;103(9):1400–1406. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ardenkjær-Larsen JH, Fridlund B, Gram A, Hansson G, Hansson L, Lerche MH, Servin R, Thaning M, Golman K. Increase in signal-to-noise ratio of > 10,000 times in liquid-state NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(18):10158–10163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1733835100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Macholl S, Jóhannesson H. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization with Trityls at 1.2 K. Appl Magn Reson. 2008;34(3):509–522. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jóhannesson H, Macholl S, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization of [1-13C]pyruvic acid at 4.6 tesla. J Magn Reson. 2009;197(2):167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waldner LF, Scholl T, Chen A, Rutt B, McKenzie C. The Effects of Contrast Agents on Hyperpolarised [1-13C]-Pyruvic Acid. Proc Int Soc Magn Reson Med. 2010:3263. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macholl S, Johannesson H, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH. Trityl biradicals and 13C dynamic nuclear polarization. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2010;12(22):5804–5817. doi: 10.1039/c002699a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koenig SH, Brown RD. Relaxation of solvent protons by paramagnetic ions and its dependence on magnetic field and chemical environment: implications for NMR imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1984;1(4):478–495. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910010407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon J, Rowland I, Peterson E, Fain S. Effect of Lanthanide Ions on Dynamic Nuclear Polarization Enhancement and Liquid State T1 Relaxation. Proc Int Soc Magn Reson Med. 2011:1512. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benmelouka M, Van Tol J, Borel A, Port M, Helm L, Brunel LC, Merbach AE. A High-Frequency EPR Study of Frozen Solutions of GdIII Complexes: Straightforward Determination of the Zero-Field Splitting Parameters and Simulation of the NMRD Profiles. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;128(24):7807–7816. doi: 10.1021/ja0583261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atsarkin VA, Demidov VV, Vasneva GA, Odintsov BM, Belford RL, Radüchel B, Clarkson RB. Direct Measurement of Fast Electron Spin-Lattice Relaxation: Method and Application to Nitroxide Radical Solutions and Gd3+ Contrast Agents. J Phys Chem A. 2001;105(41):9323–9327. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherry AD, Caravan P, Lenkinski RE. Primer on gadolinium chemistry. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;30(6):1240–1248. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terreno E, Botta M, Boniforte P, Bracco C, Milone L, Mondino B, Uggeri F, Aime S. A Multinuclear NMR Relaxometry Study of Ternary Adducts Formed between Heptadentate GdIII Chelates and L-Lactate. Chem Eur J. 2005;11(19):5531–5537. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terreno E, Botta M, Dastrù W, Aime S. Gd-enhanced MR images of substrates other than water. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2006;1(3):101–105. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy PS, Leach MO, Rowland IJ. The effects of paramagnetic contrast agents on metabolite protons in aqueous solution. Phys Med Biol. 2002;47(6):N53–N59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gabellieri C, Leach MO, Eykyn TR. Modulating the relaxivity of hyperpolarized substrates with gadolinium contrast agents. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2009;4(3):143–147. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Comment A, van den Brandt B, Uffmann K, Kurdzesau F, Jannin S, Konter JA, Hautle P, Wenckebach WT, Gruetter R, van der Klink JJ. Design and performance of a DNP prepolarizer coupled to a rodent MRI scanner. Concepts Magn Reson B. 2007;31B(4):255–269. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lettvin J, Dean Sherry A. Gd(TTHA): An aqueous carbon-13 relaxation reagent. Journal of Magnetic Resonance (1969) 1977;28(3):459–461. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borel A, Helm L, Merbach AE. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of MRI-Relevant GdIII Chelates: Direct Access to Outer-Sphere Relaxivity. Chem Eur J. 2001;7(3):600–610. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20010202)7:3<600::aid-chem600>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Das S, Bhattacharyya J, Mukhopadhyay S. Mechanistic Studies on the Oxidation of Glyoxylic and Pyruvic Acid by a [Mn4O6]4+ Core in Aqueous Media: Kinetics of Oxo-Bridge Protonation. Helvetica Chimica Acta. 2006;89(9):1947–1958. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morcos SK. Extracellular gadolinium contrast agents: Differences in stability. European Journal of Radiology. 2008;66(2):175–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keshari KR, Wilson DM, Chen AP, Bok R, Larson PEZ, Hu S, Criekinge MV, Macdonald JM, Vigneron DB, Kurhanewicz J. Hyperpolarized [2-13C]-Fructose: A Hemiketal DNP Substrate for In Vivo Metabolic Imaging. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(48):17591–17596. doi: 10.1021/ja9049355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gallagher FA, Kettunen MI, Day SE, Hu D-e, Karlsson M, Gisselsson A, Lerche MH, Brindle KM. Detection of tumor glutamate metabolism in vivo using 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy and hyperpolarized [1-13C]glutamate. Magn Reson Med. 2011;66(1):18–23. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Golman K, Ardenkjær-Larsen JH, Petersson JS, Månsson S, Leunbach I. Molecular imaging with endogenous substances. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(18):10435–10439. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1733836100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alsaadi BM, Rossotti FJC, Williams RJP. Hydration of complexone complexes of lanthanide cations. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 1980;11:2151–2154. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peters JA, Huskens J, Raber DJ. Lanthanide induced shifts and relaxation rate enhancements. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 1996;28(3–4):283–350. [Google Scholar]