Abstract

Introduction:

Alcea rosea L. is used in Asian folk medicine as a remedy for a wide range of ailments. The aim of the present study was to investigate the effect of hydroalcoholic extract of Alcea rosea roots on ethylene glycol-induced kidney calculi in rats.

Materials and Methods:

Male Wistar rats were randomly divided into control, ethylene glycol (EG), curative and preventive groups. Control group received tap drinking water for 28 days. Ethylene glycol (EG), curative and preventive groups received 1% ethylene glycol for induction of calcium oxalate (CaOx) calculus formation; preventive and curative subjects also received the hydroalcoholic extract of Alcea rosea roots in drinking water at dose of 170 mg/kg, since day 0 or day 14, respectively. Urinary oxalate concentration was measured by spectrophotometer on days 0, 14 and 28. On day 28, the kidneys were removed and examined histopathologically under light microscopy for counting the calcium oxalate deposits in 50 microscopic fields.

Results:

In both preventive and curative protocols, treatment of rats with hydroalcoholic extract of Alcea rosea roots significantly reduced the number of kidney calcium oxalate deposits compared to ethylene glycol group. Administration of Alcea rosea extract also reduced the elevated urinary oxalate due to ethylene glycol.

Conclusion:

Alcea rosea showed a beneficial effect in preventing and eliminating calcium oxalate deposition in the rat kidney. This effect is possibly due to diuretic and anti-inflammatory effects or presence of mucilaginous polysaccharides in the plant. It may also be related to lowering of urinary concentration of stone-forming constituents.

KEY WORDS: Alcea rosea, malvaceae, kidney calculi, ethylene glycol, calcium oxalate

Introduction

Urolithiasis is a worldwide problem, sparing no geographical, cultural, or racial groups.[1] It is largely a recurrent disease with a relapse rate of 50% in 5-10 years, and therefore a condition with substantial economic consequences and a great public health importance.[1,2] Calcium oxalate (CaOx) and calcium phosphate stones are the highest common calculi which form approximately 80% of stones in the urinary system.[3,4] Uric acid stones represent about 5-10%, trailed by cystine, struvite, and ammonium acid urate stones.[1] Endoscopic stone removal and extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) are widely used to remove the calculi. However, in addition to the traumatic effects of shock waves, persistent residual stone fragments, and the possibility of infection, suggest that ESWL may cause acute renal injury, a decrease in renal function and an increase in stone recurrence.[5,6] Therefore, it is worthwhile to look for alternative treatments by using medicinal plants or phytotherapy to replace these modern methods. Several pharmacological investigations on the medicinal plants used in traditional antiurolithic therapy have revealed their therapeutic potential in the in vitro or in vivo models.[7–11]

Alcea rosea L. (Malvaceae), populary known as Holyhock, is widely grown in gardens and parks in the Southern Europe and Asia. Several pharmacological studies have reported that this plant possesses anti-inflammatory, antibacterial and analgesic effects.[12–14] The roots of Alcea rosea has been used in Iranian traditional medicine for a wide range of ailments, including bronchitis, diarrhoea, constipation, inflammation, severe coughs and angina.[15,16] However, the most important activities of the plant has been attributed to its diuretic effects. Alcea rosea has been used as a cure for dysuria and strangury and for stones in the kidney.[15,16] However, there is no report in the literature on the effect of Alcea rosea on kidney stones. Therefore, in this study we investigated the antiurolithic effect of Alcea rosea root extract using ethylene glycol-induced kidney calculi model in the rat.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Plant Extract

The roots of Alcea rosea, cultivated in Mazandaran State (Iran), were purchased from Imam Reza Pharmacy and graciously identified by Ferdowsi University herbarium (Mashhad, Iran). The roots (120 g) were powdered and then extracted with ethanol (70%) in a Soxhlet extractor. The resulting extract was concentrated under reduced pressure and kept at 4°C until use.

Experimental Protocol

Curative and preventive protocols were designed to evaluate the effectiveness of Alcea rosea on kidney calculi in male Wistar rats. The experiments were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the study was approved by Mashhad University of Medical Sciences.

Male Wistar rats weighing 240-290 g were housed at 25 ± 2°C on a standard diet and tap drinking water. They were randomly divided into control, ethylene glycol (EG), curative and preventive groups and treated according to the experimental protocols for 28 days. Rats in control group (n=5) received tap drinking water. Ethylene glycol (EG) (n=8), curative and preventive groups all received 1% ethylene glycol (Merck, Germany) in drinking water for 28 days.[17] Preventive and curative groups (n=7 in each group) were also treated with hydroalcoholic extract of Alcea rosea roots at dose of 170 mg/kg, since day 0 or day 14, respectively.

Sampling for Biochemical Analysis

Animals were kept separately in metabolic cages and acclimatized for at least 1 day before treatment. Twenty-four -hour urine were collected on days 0, 14 and 28 with clean metabolic cages. The urine specimens were quickly kept frozen at -20°C until biochemical analysis by Spectrophotometer (Jenway, England).

Histopathology Examination

At the end of the experiment (day 28), all rats were anesthetized by diethyleter and the kidneys were removed. For histological processing, the kidneys were fixed in 10% formalin, dehydrated in a gradient of ethanol, embedded in paraffin and cut into 5-μm serial sections. Ten slides containing five sections from each kidney were deparaffinized, stained with hematoxylin-eosin and examined by light microscope. Aggregations of CaOx deposits (tubules containing CaOx deposits) were counted in 50 microscopic fields.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) followed by Tukey post hoc test. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM for each group. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

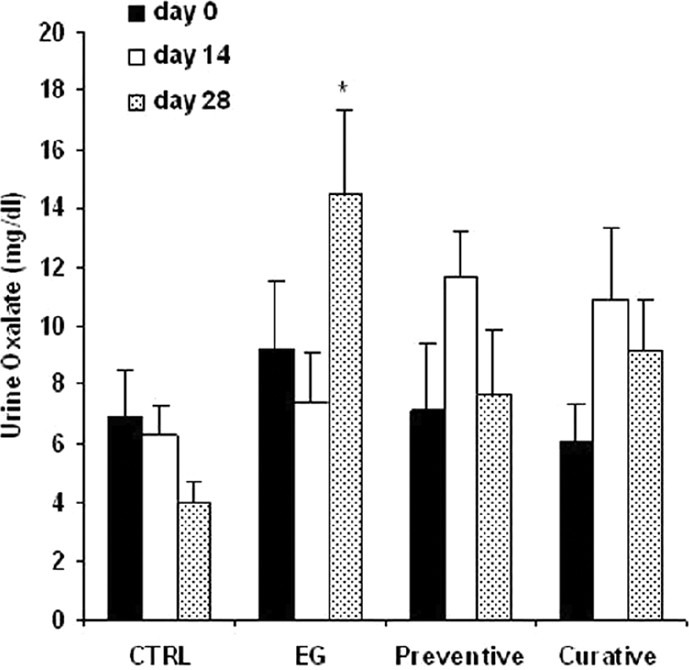

As shown in Figure 1, there was no difference in urine oxalate levels between 4 groups on day 0. On day 28, those in ethylene glycol group had a significantly higher urine oxalate concentration in comparison with the rats in control group [P<0.05, Figure 1]. In preventive and curative groups, the urine oxalate levels reduced to 47% and 37% of those in ethylene glycol group, respectively.

Figure 1.

Urine oxalate concentration in experimental groups. CTRL= control group (n =5), EG=ethylene glycol group (n =8), Preventive and Curative (n =7 in each): groups treated with hydroalcoholic extract of Alcea rosea(175 mg/kg) since day 0 or day 14, respectively, through the end of the experiment. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM, *P<0.05 vs. control group

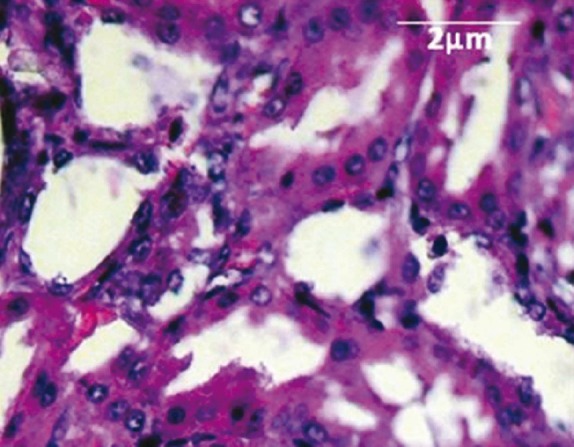

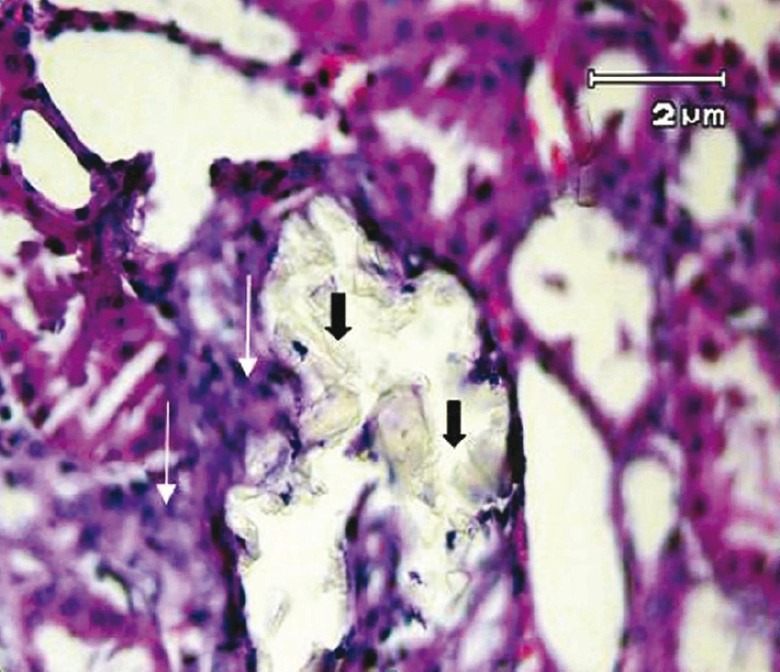

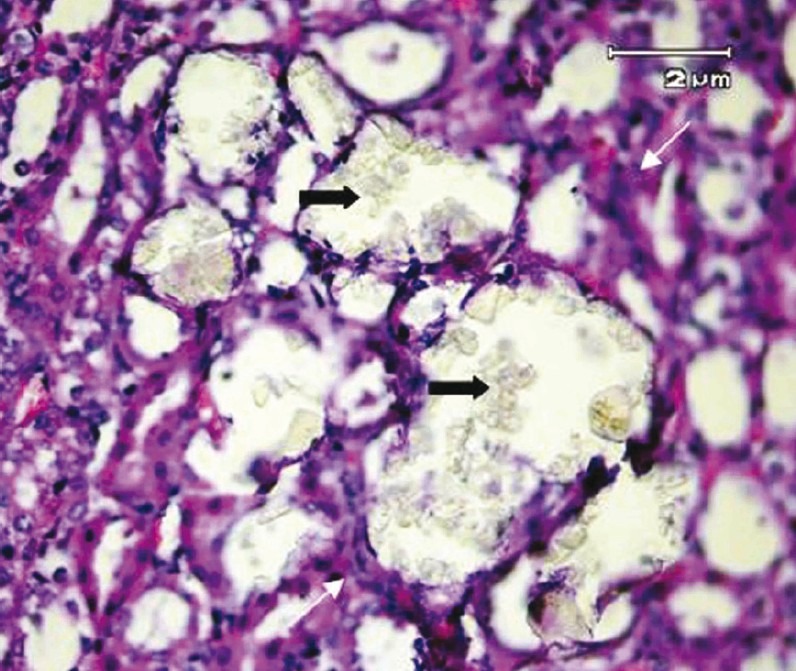

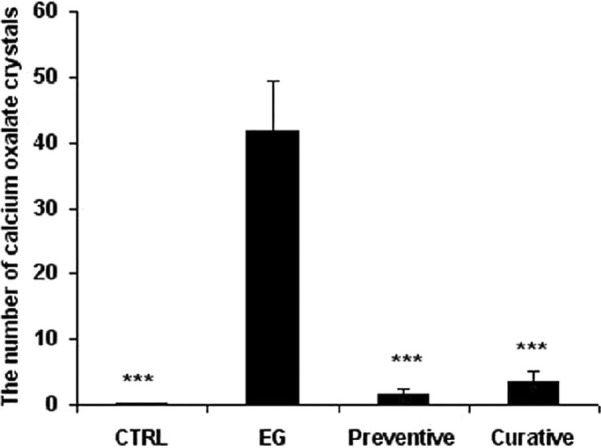

The examination of kidney sections in control group showed no calcium oxalate deposits or other abnormalities in different segments of the nephrons [Figure 2]. But in EG group, calcium oxalate deposits were abundantly found in different segments of the nephron, including proximal tubules, loops of Henle, distal tubules, collecting ducts, and even kidney calyxes [Figures 3 and 4]. Deposits in different segments of the renal tubules were composed of 3-4 large polygonal crystals. Renal tubular dilation with epithelial damage and leukocyte reaction were also observed on pathology examination [Figure 4]. The average number of calcium oxalate deposits in 50 microscopic fields in the kidney specimens of EG group was 41.85 ± 7.6, which was significantly higher than control group [P<0.001; Figure 5]. In preventive group, the number of deposits was 1.71 ± 0.73, which was significantly lower than that in EG group [P<0.001; Figure 5]. In curative group, the number of deposits was 3.64 ± 1.53, which was significantly lower than EG group [P<0.001; Figure 5]. Also, calcium oxalate crystals in different parts of the curative and preventive groups renal tubules were clearly smaller in comparison with EG group.

Figure 2.

Normal tubules and collecting ducts (H&E, × 400)

Figure 3.

Multiple tubular calculi (black arrows) and inflammatory infiltration (white arrows) has been shown in ethylene glycol-treated group (H&E, × 400)

Figure 4.

Renal tubular dilation and epithelial damage secondary to multiple calculi (black arrows) accompanied with inflammatory infiltration (white arrows) in peritubular space. (H&E, × 400)

Figure 5.

The number of calcium oxalate crystal deposits in 50 microscopic fields of experimental groups. CTRL: control group (n =7), EG: ethylene glycol group (n =7), Preventive and Curative (n =7 in each): groups treated with hydroalcoholic extract of Alcea rosea (175 mg/kg) since day 0 or day 14, respectively, through the end of the experiment. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM, *P<0.001 vs. ethylene glycol group

Discussion

This study showed that the hydroalcoholic extract of Alcea rosea root had a preventive effect on CaOx calculus formation in the rat kidney. In addition, Alcea rosea decreased the number of CaOx calculi in the treated group, demonstrated a curative effect on the disruption of CaOx calculi formed in the kidney due to ethylene glycol consumption.

To our best of knowledge, this is the first report on the effect of hydroalcoholic extract of Alcea rosea on prevention and treatment of CaOx kidney calculus.

The basis for calcium stone formation is supersaturation of urine with stone-forming calcium salts. A number of dietary factors and metabolic abnormalities can change the composition or saturation of the urine so as to enhance stone-forming propensity. Among the metabolic conditions are hypercalciuria, hypocitraturia and hyperoxaluria.[18] However, the role of other factors like inhibitors, infection, matrix formation as well as urinary obstruction should not be ignored.[19]

There is evidence that in response to ethylene glycol administration, young male Albino rats form renal calculi composed mainly of calcium oxalate.[7,20,21] Stone formation in ethylene glycol fed animals is caused by hyperoxaluria, which causes increased excretion of oxalate and its urinary concentration.[20] Therefore, this model was used to evaluate the effect of Alcea rosea root extract on calcium oxalate urolithiasis.

Consistent with some previous reports, stone induction by ethylene glycol caused an increase in oxalate excretion[20,22] and cotreatment with Alcea rosea root extract reduced the rate of increase in the oxalate excretion.

The exact mechanisms involved in the effect of Alcea rosea on CaOx calculi are not clear; however, the following mechanisms are possible.

Firstly, hyperoxaluria is a major risk factor in calcium oxalate stone formation; the hydroalcoholic extract of Alcea rosea was able to reduce the urine oxalate in treatment groups on day 28. Thus, it seems that the preventive effect of Alcea rosea extract on CaOx formation can be in part attributed to alteration of urine oxalate concentration. Alcea rosea could possibly control the levels of oxalate by inhibiting the synthesis of oxalate.

Secondly, since the concentration rather than the amount of the crystallising solutes is what ultimately establishes stone formation, reduced urinary volume will amplify the saturation of all solutes and raise the risk of all stone formation.[1] It has been reported that Alcea rosea has diuretic activity,[15] so the curative and prophylactic treatment with Alcea rosea extract causes diuresis and it can hasten the process of dissolving the preformed stones and prevention of new stone formation in urinary system.

Thirdly, acute and chronic production of calcium oxalate and crystal deposition induces lipid peroxidation. The generation of lipid peroxidation due to reactive oxygen species causes renal epithelial cell injury which promotes calcium oxalate stone formation by providing cellular debris for crystal nucleation and aggregation, and augments crystal attachment to other tubular cells.[23] Several studies have reported that Alcea possesses anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties.[15,16,24,25] Therefore, the role of Alcea rosea in preventing formation of CaOx calculi and disruption of them, as seen in the present study, may be in part due to the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of the different compounds of Alcea rosea. These compounds may interfere with the process of epithelial cell damage induced by crystals or may exert inhibitory effect on inflammation.

Fourthly, the plant extract may interfere directly in the inhibition of crystal adhesion to the epithelium by blocking the attachment sites located either into the cell surfaces or into the surface of the crystals themselves. It has been reported that Alcea rosea roots contain bioadhesive and mucilaginous polysaccharides,[26,27] leading to the physical formation of mucin-like substances which coat crystals and block their adhesion to the cell surface.

Finally, It has also been reported that CaOx calculi such as struvite calculi may have a bacterial origin such as nanobacteria.[28] Alcea rosea also has antibacterial effects[12,14] and therefore, may be effective in this mechanism of CaOx calculus formation.

Conclusions

Overall, the results indicate that administration of the hydroalcoholic extract of Alcea rosea root, at dose of 170 mg/ kg, to rats with ethylene glycol-induced lithiasis, reduced and prevented the growth of urinary stones, supporting folk information regarding antiurolithiatic activities of the plant. The mechanism(s) underlying this effect is unknown, but is apparently due to its diuretic and anti-inflammatory effects, presence of mucilaginous polysaccharides, and lowering of urinary concentrations of stone-forming constituents.

Acknowledgment

This study was financially supported by a grant from the Council of Research, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Grant from the Council of Research, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Moe OW. Kidney stones: Pathophysiology and medical management. Lancet. 2006;367:333–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moro FD, Mancini M, Tavolini IM, Marco VD, Bassi P. Cellular and molecular gateways to urolithiasis: A new insight. Urol Int. 2005;74:193–7. doi: 10.1159/000083547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coe FL, Evan A, Worcester E. Kidney stone disease. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2598–608. doi: 10.1172/JCI26662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menon M, Resnick MI. Urinary lithiasis: Etiology, diagnoses, and medical management. In: Walsh PC, Retik AB, Vaughan ED, Wein AJ, editors. Campbell's Urology. 8th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002. pp. 3229–305. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kishimoto T, Yamamoto K, Sugimoto T, Yoshihara H, Maekawa M. Side effects of extracorporeal shock-wave exposure in patients treated by extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy for upper urinary tract stone. Eur Urol. 1986;12:308–13. doi: 10.1159/000472644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Begun FP, Knoll CE, Gottlieb M, Lawson RK. Chronic effects of focused electrohydraulic shock-waves on renal function and hypertension. J Urol. 1991;145:635–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38410-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atmani F, Slimani Y, Mimouni M, Hacht B. Prophylaxis of calcium oxalate stone by Herniaria hirsute on experimentally induced nephrolithiasis in rats. BJU Int. 2003;92:137–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barros ME, Lima R, Mercuri LP, Matos JR, Schor N, Boim MA. Effect of extract of Phyllanthus niruri on crystal deposition in experimental urolithiasis. Urol Res. 2006;34:351–7. doi: 10.1007/s00240-006-0065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hajzadeh MA, Khoei A, Hadjzadeh Z, Parizady M. Ethanolic extract of Nigella Sativa L seeds on ethylene glycol-induced kidney calculi in rats. Urol J. 2007;4:86–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christina AJ, Packia Lakshmi M, Nagarajan M, Kurian S. Modulatory effect of Cyclea peltata Lam. on stone formation induced by ethylene glycol treatment in rats. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2002;24:77–9. doi: 10.1358/mf.2002.24.2.677130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grases F, Ramis M, Costa-Bauzá A, March JG. Effect of Herniaria hirsuta and Agropyron repens on CaOx urolithiasis risk in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 1995;45:211–4. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(94)01218-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang DF, Shang JY, Yu QH. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of the flower of Althaea rosea (L.) Cav. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 1989;14:46–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mert T, Fafal T, Kıvcak H, Tansel Ozturk H. Antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of the extracts obtained from the flowers of Alcea rosea L. Hacet Univ J Pharm. 2010;30:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seyyednejad SM, Koochak H, Darabpour E, Motamedi A survey on Hibiscus rosa—sinensis, Alcea rosea L. and Malva neglecta Wallr as antibacterial agents. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2010;3:351–5. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zargari A. Alcea rosea L. In: Medicinal Plants. Vol. 1. Tehran: Tehran University Press; 1992. pp. 360–3. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aghili Khorasani MH. Makhzan-Al-Adviah. Tehran: Islamic Publishing and Educational Organization; 1992. p. 394. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hajzadeh MA, Mohammadian N, Rahmani Z, Behnam F. Effect of thymoquinone on ethylene glycol-induced kidney calculi in rats. Urol J. 2008;5:149–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park S, Pearle MS. Pathophysiology and management of calcium stones. Urol Clin North Am. 2007;34:323–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller NL, Evan AP, Lingeman JE. Pathogenesis of renal calculi. Urol Clin North Am. 2007;34:295–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selvam P, Kalaiselvi P, Govindaraj A, Murugan VB, Sathishkumar AS. Effect of A. lanata leaf extract and vediuppu chunnam on the urinary risk factors of calcium oxalate urolithiasis during experimental hyperoxaluria. Pharmacol Res. 2001;43:89–93. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2000.0745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang HS, Ma MC, Chen J, Chen CF. Changes in the oxidant-antioxidant balance in the kidney of rats with nephrolithiasis induced by ethylene glycol. J Urol. 2002;167:2584–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christina AJ, Packia Lakshmi M, Nagarajan M, Kurian S. Modulatory effect of Cyclea peltata Lam. stone formation induced by ethylene glycol treatment in rats. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2002;24:77–9. doi: 10.1358/mf.2002.24.2.677130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thamilselvan S, Khan SR, Menon M. Oxalate and calcium oxalate mediated free radical toxicity in renal epithelial cells: Effect of antioxidants. Urol Res. 2003;31:3–9. doi: 10.1007/s00240-002-0286-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghaoui WB, Ghanem EB, Chedid LA, Abdelnoor AM. The effects of Alcea rosea L., Malva sylvestris L. and Salvia libanotica L. water extracts on the production of anti-egg albumin Antibodies, interleukin-4, gamma interferon and interleukin-12 in BALB/c, mice. Phytother Res. 2008;22:1599–604. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kardosova A, Machova E. Antioxidant activity of medicinal plant polysaccharides. Fitoterapia. 2006;77:367–73. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Classen B, Blaschek W. High molecular weight acidic polysaccharides from Malva sylvestris and Alcea rosea. Planta Med. 1998;64:640–4. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deters A, Zippel J, Hellenbrand N, Pappai D, Possemeyer C, Hensel A. Aqueous extracts and polysaccharides from Marshmallow roots (Althea officinalis L.): Cellular internalisation and stimulation of cell physiology of human epithelial cells in vitro. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;127:62–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kramer G, Klingler HC, Steiner GE. Role of bacteria in the development of kidney stones. Curr Opin Urol. 2001;10:35–8. doi: 10.1097/00042307-200001000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]