Abstract

Background:

The study was planned to assess the comparative efficacy, safety and duration of analgesia produced by low-dose clonidine and midazolam when used as adjuvant for spinal anesthesia.

Materials and Methods:

This is a randomized, participant and observer blind, prospective, parallel group clinical trial. Fifty ASA grade I and II patients posted for lower abdominal surgery were randomly allocated into two groups. BC group received spinal clonidine 30 μg and BM group received preservative-free midazolam 2 mg with 15 mg hyperbaric bupivacaine. Postoperative analgesia, analgesic requirement in 24 hours, onset and duration of block, hemodynamic stability and adverse effects were observed (P<0.05 – considered significant, P<0.01 considered highly significant).

Results:

The duration of postoperative analgesia was prolonged in BM group (391.64 ± 132.98 min) than BC group (296.60 ± 52.77 min) (P<0.01). The mean verbal rating pain score was significantly less in BM group than BC group (P<0.01). The number of analgesic doses in 24 hours were significantly less in BM group (P<0.05). Nine patients (36%) in BC group required additional analgesia as against none in BM group (P<0.01). The onset of sensory block and peak sensory level was significantly earlier in BM group as compared to BC group. Duration of sensory block was longer in BM group (P<0.05). Subjects in BC group(36%) had bradycardia as compared to none in BM group (P<0.01). Hypotension was observed in 44% patients in BC group as against 16% in BM group (P<0.05).

Conclusion:

Postoperative analgesia with clonidine is short lived with some bradycardia. Intrathecal midazolam provides superior analgesia without clinically relevant adverse effects.

KEY WORDS: Spinal anesthesia, postoperative analgesia, hyperbaric bupivacaine, intrathecal midazolam, intrathecal clonidine, lower abdominal surgery

Introduction

Spinal anesthesia with local anesthetic agents and adjuvant is extensively used for lower abdominal surgery. The analgesia extends for variable duration in the postoperative period. It provides excellent pain relief as compared to intravenous or epidural route.[1] Neuraxial opioids have effective postoperative analgesia without sensory or motor blockade.[2] But in spite of ease of administration and patient comfort, worrisome adverse effects like potentially catastrophic respiratory depression, urinary retention, vomiting, pruritus, etc., limit their use in rural health care setup.[3] This has promoted researchers to investigate non-opioid compounds with analgesic property and less worrisome adverse effects. Intrathecal (IT) midazolam and clonidine produce a dose dependent anti-nociception when used alone or in combination with local anesthetics.[4,5] They improve intraoperative analgesia, prolong duration of sensory and motor blockade along with sparing effect on postoperative analgesic consumption.[6–8] The incidence of hypotension, bradycardia and sedation observed with intrathecal clonidine in earlier studies is reduced using low dose of clonidine (<150 μg).[9,10] No study is available to establish the superiority of either agent for postoperative analgesia after neuraxial administration. This randomized, observer blind clinical trial was designed to assess the comparative efficacy, safety and duration of analgesia produced by low dose clonidine and preservative free midazolam when used as adjuvant for spinal anesthesia with hyperbaric bupivacaine.

Materials and Methods

This randomized, prospective, double blind, parallel group clinical trial was conducted during April 2009 and July 2011, in accordance with the principles laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by Institutional Ethics Committee. The plan of study, anticipated benefits and possible side effects were explained to the patients along with assurance that he/she can withdraw at any time from the trial. Written informed consent was obtained and use of Verbal rating pain scale (VRS) was explained during preoperative visit. Fifty American Society of Anaesthesiologist Grade I and II subjects of age between 20 and 65 years, presenting for lower abdominal surgery under spinal anesthesia from gynecology and general surgery at a tertiary health care center in a rural area were enrolled in the study. Patients with psychiatric disorders, chronic pain or any condition that precludes spinal anesthesia or those taking antihypertensive medication were excluded. Premedication with oral diazepam 5 mg administered at bed time, intravenous (IV) ranitidine 50 mg and ondansetron 4 mg was administered just before induction of anesthesia. Intravenous access was established with 18-G cannula followed by preloading with 10 ml/kg lactated ringers solution. Standard monitoring was used (ECG, noninvasive blood pressure and pulse oximetry) during surgery.

Conduct of Study

Fifty subjects were randomly assigned into one of the two treatment groups, BM or BC using a random number table with allocation ratio 1:1. The serial number and group of allocation of each subject recorded in two separate papers which were packed in opaque envelop impermeable to intense light and sealed. The allocation sequence was concealed from the researcher enrolling and assessing the participants. Only the serial number was entered on proforma sheet of individual subject. The chits were put in the same envelop and stapled back to be reopened at the conclusion of the study. The investigator involved in sequence generation and allocation concealment was blinded to this process. The participant and data collector both were blinded to the test solution.

The test solutions were prepared in identical syringes by anesthesiologist not involved in patient monitoring. Spinal anesthesia (SA) was performed at lumbar 3-4 intervertebral space using 23-G disposable spinal needle in right lateral position. After free flow of CSF, one of the study solutions was injected intrathecally at the rate 0.2 ml per second. BM group (Midazolam group) received 15 mg 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine and 2 mg preservative-free midazolam (Midazolam hydrochloride-5 mg/ml-Midosed, Neon laboratories) made 3.5 ml with normal saline whereas BC group (Clonidine group) received 15 mg 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine and 30 μg preservative-free clonidine (Clonidine hydrochloride-150 μg/ ml-Cloneon, Neon laboratories) made 3.5 ml with normal saline. The time of intrathecal (IT) injection was noted and patient put in supine position. Sensory block was assessed by loss of sensation to pin prick at every 2 minutes intervals for 15 min, then every 10 min until maximum sensory level was achieved. Motor block was assessed as inability to move lower limbs. A dermatomal sensory loss from dorsal 8 to sacral 4 segments was considered satisfactory. The level of sedation was recorded every 15 minutes intraoperatively and postoperatively for 6 hours by sedation score described by Chernik et al. i.e., no sedation (wide awake), mild sedation (sleeping comfortably), moderate sedation (deep sleep but arousable) and severe sedation (deep sleep not arousable).[4] Supplemental oxygen via ventimask was given at 3l/minute during the procedure. Pulse rate, blood pressure and oxygen saturation (SpO2) was recorded every 5 minutes for 15 minutes, then every 10 minutes till end of surgery and 2,4,6,12,24 hours, postoperatively. IV fluids (crystalloids, colloids or blood) were administered for maintenance and according to surgical blood loss. Hypotension was defined as systolic BP <90 mmHg or 20% fall in systolic BP from baseline value, and treated with 250 ml bolus IV fluids and IV mephenteramine 6 mg. Bradycardia was defined as pulse rate <60/min and treated with IV atropine sulfate 0.6 mg. Each patient received intramuscular diclofenac sodium 75 mg postoperatively. Further analgesic dose was administered on patient's demand. If pain persisted (VRS > 5), tramadol 1 mg/ kg was administered intravenously.

The primary outcome measure was duration of postoperative analgesia i.e., time from IT injection till demand for rescue analgesic or VRS > 5. Pain score was recorded every 2 hours until first rescue analgesic dose. The total number of analgesic doses in 24 hours was recorded. Data was collected regarding the onset of sensory block (Time taken from IT injection to loss of pinprick sensation bilaterally at L1), maximum sensory level, time to achieve maximum sensory level, duration of sensory block (Time from IT injection to 2 segment regression) and duration of motor block (Time from IT injection till appearance of leg movements) Adverse effects like hypotension, bradycardia, sedation, nausea, vomiting, respiratory depression (SpO2 < 90%) shivering, itching, drowsiness, headache bowel/bladder dysfunction, neurological deficit before discharge, etc. were recorded as and when they occurred. IV metoclopramide 10 mg was administered as rescue antiemetic. Each subject was observed for 24 hours after surgery. The recruitment stopped after enrolling 25 participants in each group.

The sample size of 25 subjects per group was necessary for detecting clinically significant difference of 60 minutes in duration of analgesia assuming a power of 90% and a significance level of 5% using the formula –

n = (u + v)2 × (SD12 + SD22) / (μ1 - μ2)2

Where u=1.28 is the percentage point of normal distribution for power 90%, v=1.96 is percentage point of normal distribution corresponding to significance level 5%, SD1=2.51 hours is standard deviation of reference study for duration of analgesia in minutes for midazolam, SD2=44.34 minutes is standard deviation of reference study for duration of analgesia of 30 μg clonidine, μ1 – μ2=60 minutes is the target difference in duration of postoperative analgesia.[3,10] The sample size was confirmed after statistical analysis using actual values obtained in the study.

Statistical Analysis

The data was analyzed using online statistical calculators GraphPad Quickcals 2005 by GraphPad Software Inc., USA and easycalculation.com. The data was presented as mean (SD), counts or numbers with percentage. Continuously distributed variables (pulse rate, systolic BP and SpO2) were analyzed using Student's unpaired t-test. Categorical data (peak sensory level, side effects and additional analgesic requirement) was analyzed using Chi-square test. The Mann-Whitney ‘U’ test was used to compare the duration of analgesia, pain score, diclofenac requirement in 24 hours, onset and duration of sensory and motor block. valueof P<0.05 is considered statistically significant and P<0.01 considered highly significant.

Results

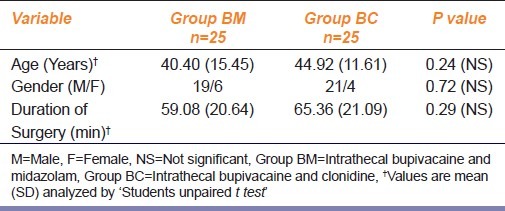

Fifty patients were analyzed in two groups of 25 each. All blocks were tested before starting procedure and were deemed adequate for surgery. The analysis was done by original assigned group of investigators. There was no dropout, refusal or any departure from initial study protocol. The two groups of patients were comparable with respect to age, sex and duration of surgery [Table 1]. The surgical procedures performed were herniorrhaphy, abdominal hysterectomy, appndicectomy, vaginal hysterectomy and Frayer's prostatectomy.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and duration of surgery in midazolam and clonidine groups

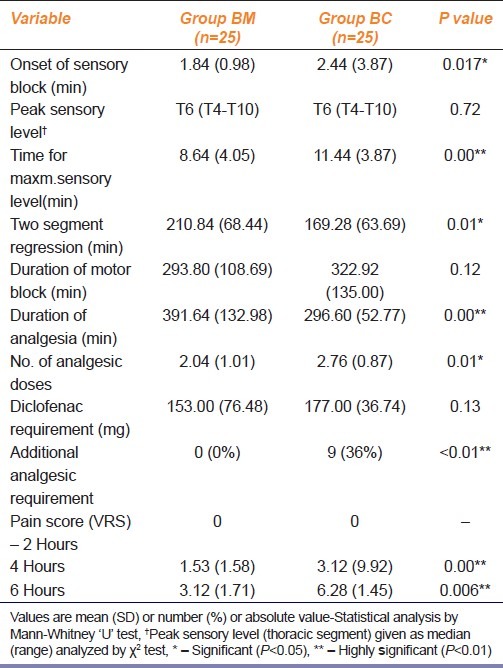

Table 2 describes the characteristics of spinal anesthesia. The mean time of onset of sensory block and the peak sensory level was significantly earlier in BM group as compared to BC group (P<0.05). The duration of sensory block was significantly longer in BM group (P<0.05). The maximum level of sensory block and duration of motor block were comparable in both the groups. The duration of pain free period was significantly prolonged in BM group than BC group (P<0.01). The mean VRS at 4 hours and 6 hours was significantly less in BM group than BC group (P<0.01). Similarly the number of injections of diclofenac were significantly less in BM group than BC group (P<0.05). Nine patients (36%) in BC group required additional analgesia as against none in BM group (P<0.01). The total amount of diclofenac administered in 24 hours was comparable in both groups.

Table 2.

Effect of intrathecal midazolam and clonidine on characteristics of spinal blockade, duration postoperative analgesia and analgesic requirement

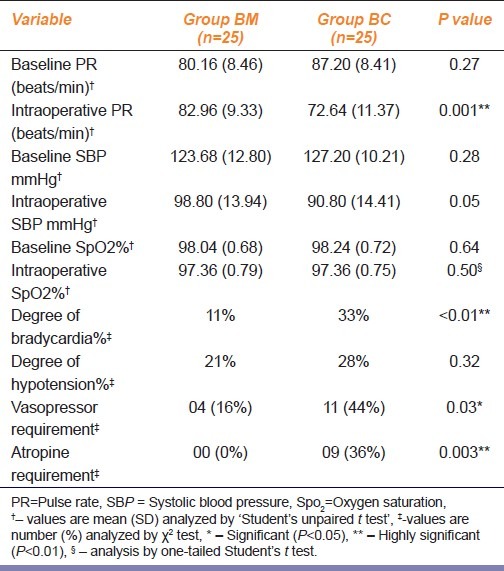

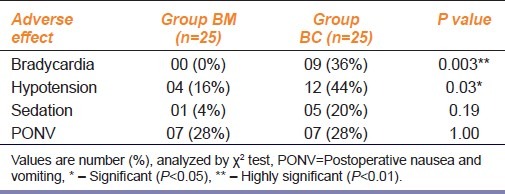

The difference in baseline pulse rate, systolic BP, preoperative and intraoperative systolic BP was not statistically significant [Table 3]. The comparative intraoperative pulse rate was lower in BC group (P<0.01). As compared to preoperative values within the group, nine subjects (36%) in BC group had bradycardia requiring atropine as compared to none in BM group (P<0.05). The degree of fall in pulse rate was 28% in BC group as against 21% in BM group (P<0.05). Hypotension was observed in 11 (44%) patients in BC group as against four patients (16%) in BM group (P<0.05). The degree of fall in systolic BP (SBP) was 33% in BC group and 11% in BM group (P<0.05). But the vasopressor requirement was not significant. Bradycardia was observed at 10-40 minutes and hypotension at 10-30 minutes or one hour after IT clonidine. Episodes of bradycardia, excessive sedation or dizziness were not recorded with IT midazolam. Mild sedation was noted in 5 (20%) subjects in BC group and in 1 subject (4%) in BM group (P>0.05). Postoperative vomiting was reported in 7 (28%) patients in each group [Table 4].

Table 3.

Variation in vital parameters after intrathecal midazolam and clonidine when used as adjuvant to spinal anesthesia with hyperbaric bupivacaine

Table 4.

Incidence of adverse effects after intrathecal midazolam and clonidine when used as adjuvant to spinal anesthesia with hyperbaric bupivacaine

Adverse effects like shivering, itching, drowsiness, headache bowel/bladder dysfunction or neurological deficit at discharge were not detected with either agent. The SpO2 was comparable at all points in both the group.

Discussion

Our study confirms the analgesic efficacy of both IT midazolam and low-dose clonidine when added to hyperbaric bupivacaine for spinal anesthesia. We observed better quality of analgesia with IT midazolam with earlier onset, little time to reach the peak sensory level and, long duration of block as compared to IT clonidine. The postoperative analgesia was maintained for longer period along with significantly less pain score and less analgesic consumption. Additional analgesia was not required in any patient in this group. Thus the null hypothesis was rejected with effective analgesia of midazolam lasting for 391.64 minutes as compared to 296.60 minutes with clonidine. Our results correspond to previously reported data in different studies when IT midazolam or clonidine alone was compared with placebo.[11–14] The peak sensory level attained was similar in both groups as the total volume and dose of bupivacaine injected was identical and not affected by either agent. We administered first dose of diclofenac 75 mg to all the patients immediately after shifting in ward for ethical reasons as per the standard protocol of our hospital. Further analgesic was administered on demand. This might be responsible for insignificant difference in amount of diclofenac requirement. But the effectiveness of midazolam was indicated by lower pain score in this group.

Several investigators have shown that intrathecal midazolam produces a dose dependent anti-nociception sufficient to produce anesthesia for abdominal surgery.[15] Patients do not require opioid analgesic when subjected to painful somatic stimulus like leg surgery.[16] It also suppresses reflex response to visceral distension in rabbits and in humans during Cesarean section.[17,18] It is effective in relieving chronic mechanical low back pain as well as pain due to metastatic bone tumors.[15] Sympathetic nervous system function remains intact after intrathecal midazolam.[3,16,19] This sparing effect on sympathetic nervous system may explain lesser degree of hypotension and bradycardia in midazolam group in our study.

Three possible mechanisms are suggested for the anti-nociceptive action of midazolam. First the benzodiazepine/GABA-A receptor complex mediated analgesia as they are abundantly present in lamina II of dorsal horn of spinal cord.[20,21] It also causes release of endogenous opioid acting at spinal delta receptors as naltrinadole, a delta receptor opioid antagonist suppresses its analgesic effect.[22] Thirdly it inhibits adenosine uptake or enhances adenosine release.[19] The use of IT midazolam in humans is reported in at least 18 peer reviewed reports in about 797 patients since 1986. In a prospective observational study, 1100 patients received intrathecal midazolam for various surgical procedures under spinal anesthesia. Increase in symptoms suggestive of neurological impairment including motor or sensory changes and bladder or bowel dysfunction were not observed.[6] Intrathecal midazolam has been shown to be free of neurotoxicity or other adverse effects up to 2-mg dose and in continuous infusion up to 6 mg/day for long periods in man.[3,6,23,24] We did not observe any cloudiness or precipitation after aspiration of CSF during injection.

Clonidine Effects and Side Effects

Clonidine, a selective α-2 adrenergic agonist produces analgesia by sympatholysis at peripheral level, decreased catecholamine release in the brain and suppression of tumor necrosis factor alpha in plasma during perioperative period. Spinal clonidine produces dose dependent analgesia along with hypotension, bradycardia and sedation.[6,10,14] Most of the studies using 37.5-50 μg reported significant hypotension and bradycardia.[9,10] A 30-μg dose provides maximum benefits and minimum side effects.[10] It also directly decreases mean arterial pressure by inhibition of preganglionic sympathetic neurons in spinal cord.[6,25] Decrease in heart rate is due to presynaptic mediated inhibition of norepinephrine release and by a direct depression of AV nodal conduction after systemic absorption. IT clonidine may be systemically absorbed; the hemodynamic effects after neuraxial administration begins within 20-30 minutes reach maximum effect within 1-2 hours after single injection. We observed some amount of bradycardia (36%) and hypotension (44%) with even low-dose clonidine. Sympatholysis of spinal anesthesia might have added to this effect. Sedation represents an α-2 adrenergic effect reversed by specific antagonist yohimbine.[6,10,14] We observed sedation in 20% subjects with IT clonidine. Although mild sedation is a desirable effect in postoperative patient, possibility of respiratory depression is well suspected. It has been reported that increase in baricity of clonidine solution or use along with hyperbaric bupivacaine reduces side effects.[25] We preferred to use sedation score and SpO2 as the indicators of respiratory depression over respiratory rate. Therefore, hemodynamic depression after IT clonidine require careful monitoring of pulse rate, blood pressure and level of sedation for at least 1-2 hours as these events might be delayed till systemic absorption of drug. The incidence of PONV was reduced by both IT clonidine and midazolam from reported 45% to 28% in both groups.

All patients could be mobilized on first postoperative day. Neither midazolam nor clonidine was associated with bowel/bladder dysfunction or neurological deficit until discharge. Long-term neurological signs and symptoms could not be detected as the study period was short and due to difficulty in establishing neurotoxicity on clinical grounds. Also the study is not adequately powered to comment conclusively on adverse effects. Further trial using a larger sample size and follow-up for at least 6 weeks is required for this purpose.

Addition of intrathecal clonidine and midazolam to hyperbaric bupivacaine prolongs spinal sensory block and postoperative analgesia. Analgesia with clonidine is minor and short lived and associated with some bradycardia. Intrathecal midazolam provides superior analgesia without clinically relevant side effects. Although not registered for this purpose, intrathecal midazolam is used along with local anesthetic for SA and postoperative analgesia in many institutions in India. These effects may be valuable in prolonged surgeries.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Institutional support.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Duncan MA, Savage J, Tucker AP. Prospective audit comparing intrathecal analgesia (incorporating midazolam) with epidural and analgesia after major open abdominal surgery. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2007;35:558–62. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0703500415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saxena AK, Arava S. Current concepts in neuraxial administration of opioid and non-opioid: An overview and future perspectives. Indian J Anaesth. 2004;48:13–24. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim MH, Lee YM. Intrathecal midazolam increased the analgesic effect of spinal blockade with bupivacaine in patients undergoing haemorrhoidectomy. Br J Anaesth. 2001;86:77–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/86.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta A, Prakash S, Deshpande S, Kale K. The effect of intrathecal midazolam 2.5 mg with hyperbaric bupivacaine on postoperative pain relief in patients undergoing orthopaedic surgry. Internet J Anesthesiol. 2007;14:11. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fogarty DJ, Carabine UA, Milligan KR. Comparison of the analgesic effects of intrathecal clonidine and intrathecal morphine after spinal anaesthesia in patients undergoing total hip replacement. Br J Anaesth. 1993;71:661–4. doi: 10.1093/bja/71.5.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rathmell JP, Lair TR, Nauman B. The role of intrathecal drugs in the treatment of acute pain. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:S30–43. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000177101.99398.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shadangi BK, Garg R, Pandey R, Das T. Effect of intrathecal midazolam in spinal anaesthesia: a prospective randomized case control study. Singapore Med J. 2011;52:432–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agrawal N, Usmani A, Sehgal R, Kumar R, Bhadoria P. Effects of intrathecal midazolam bupivacaine combination on postoperative analgesia. Indian J Anaesth. 2005;49:37–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sethi BS, Samuel M, Sreevastava D. Efficacy of analgesic effects of low dose intrathecal clonidine as adjuvant to bupivacaine. Indian J Anaesth. 2007;51:415–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saxena H, Singh S, Ghildiyal SK. Low dose intrathecal clonidine with bupivacaine improves onset and duration of block with haemodynamic stability. Internet J Anesthesiol. 2010;23:14. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanad H, Abdelsalam T, Hamada M, Alsherbiny MA. Effects of adding magnesium sulphate, midazolam or ketamine to hyperbaric bupivacaine for spinal anaesthesia in lower abdominal and lower extremity surgery. Ain Shams J Anesthesiol. 2010;3:43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biswas BN, Rudra A, Saha JK, Karmarkar S. Comparative study between effects of intrathecal midazolam and fentanyl on early postoperative pain relief after inguinal herniorrhaphy. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2002;18:280–3. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarkar M, Dewoolkar L. Comparative study of intrathecal fentanyl and bupivacaine v/s midazolam and bupivacaine v/s norphine and bupivacaine in major gynaecological surgeries. Bombay Hosp J. 2007;49:448–52. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Tuijl I, van Klei WA, van der Werff DB, Kalkman CJ. The effect of addition of intrathecal clonidine to hyperbaric bupivacaine on postoperative pain and morphine requirements after caesareean section: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97:365–70. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bahar M, Cohen ML, Grinshpon Y, Chanimov M. Spinal anaesthesia with midazolam in rat. Can J Anaesth. 1997;44:208–15. doi: 10.1007/BF03013011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodchild CS, Noble J. The effects of intrathecal midazolam on sympathetic nervous system reflexes in man-a pilot study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;23:279–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1987.tb03046.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crawford ME, Jensen FM, Toftdahl DB, Madsen JB. Direct spinal effect of intrathecal and extradural midazolam on visceral noxious stimulation in rabbits. Br J Anaesth. 1993;70:642–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/70.6.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valentine JM, Lyons G, Bellamy MC. The effect of intrathecal midazolam on post-operative pain relief. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 1996;13:589–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2346.1996.00044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yaksh TL, Allen JW. The use of intrathecal midazolam in humans: A case study of process. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:1536–45. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000122638.41130.BF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohno T, Kumamoto E, Baba H, Ataka T, Okamoto M, Shimoji K, et al. Actions of midazolam on GABAergic transmission in substantia gelatinosa neurons of adult rat spinal cord. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:507–15. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200002000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwards M, Serrao JM, Gent JP, Goodchild CS. On the mechanism by which midazolam causes spinally mediated analgesia. Anesthesiology. 1990;73:273–7. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199008000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodchild CS, Guo Z, Musgreave A, Gent JP. Antinociception by intrathecal midazolam involves endogenous neurotranamitters acting at spinal cord delta opioid receptors. Br J Anaesth. 1996;77:758–63. doi: 10.1093/bja/77.6.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishiyama T, Matsukawa T, Hanaoka K. Acute phase histopathological study of spinally administered midazolam in cats. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:717–20. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199909000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tucker AP, Lai C, Nadeson R, Goodchild CS. Intrathecal midazolam I: A cohort study investigating safety. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:1512–20. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000087075.14589.F5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baker A, Klimscha W, Eisenach JC, Li XH, Wildling E, Menth-Chiari WA, et al. Intrathecal clonidine for postoperative analgesia in elderly patients: The influence of baricity on haemodynamics and analgesic effect. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:128–34. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000114549.17864.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]