Abstract

Background and Objective:

Cardiovascular disorders continue to constitute major causes of morbidity and mortality in diabetic patients. In this study, the effect of chronic administration of naringenin was investigated on aortic reactivity of streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats.

Materials and Methods:

Male diabetic rats (n=32) were divided into control, naringenin-treated control, diabetic, and naringenin-treated diabetic groups of eight animals each. The latter group received naringenin for 5 weeks at a dose of 10 mg/kg/day after diabetes induction. The contractile responses to potassium chloride (KCl) and phenylephrine (PE) and relaxation response to acetylcholine (ACh) were obtained from aortic rings. Meanwhile, participation of nitric oxide (NO) and endothelial vasodilator factors in response to ACh were evaluated using N (G)-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) and indomethacin (INDO), respectively.

Results:

Maximum contractile response of endothelium-intact rings to KCl and PE was significantly (P<0.05) lower in naringenin-treated diabetic rats as compared to untreated diabetics. Endothelium-dependent relaxation to ACh was significantly (P<0.05-0.01) higher in naringenin-treated diabetic rats as compared to diabetic ones and pretreatment of rings with nitric oxide synthase inhibitor N (G)-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) significantly (P<0.001) attenuated the observed response.

Conclusion:

Chronic treatment of diabetic rats with naringenin could prevent some abnormal changes in vascular reactivity in diabetic rats through nitric oxide and endothelium integrity is necessary for this beneficial effect.

KEY WORDS: Aorta, diabetes mellitus, naringenin, streptozotocin

Introduction

Cardiovascular disorders continue to constitute major causes of morbidity and mortality in diabetic patients in spite of significant achievements in their diagnosis and treatment.[1] Changes in vascular responsiveness to vasoconstrictors and vasodilators are mainly responsible for development of some vascular complications of diabetics.[2] Most of these complications are due to increased serum glucose and augmented generation of reactive oxygen species that lead to endothelium dysfunction.[3]

Epidemiological findings show that there exists a relationship between health maintenance and the consumption of foods rich in phenolic flavonoids.[4] Naringenin is one such naturally occurring flavanone that is mainly present in citrus fruits.[5] Naringenin treatment could prevent inflammation,[6] thrombosis,[4] tumorigenesis,[7] atherosclerosis and hypercholesterolemia.[8] Recent studies have also shown that naringenin elicits antidiabetic effect by suppressing carbohydrate absorption from the intestine, thereby reducing the postprandial increase in blood glucose levels.[9] Further, naringenin prevents hepatic steatosis and improves insulin sensitivity in animals fed a high fat diet.[8] Naringenin also induces concentration-dependent relaxation in aortic tissue from normal rats.[10] The vasorelaxant, antioxidant and cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitory effects of naringenin have also been reported in aortic tissue.[11] Until now, vasorelaxant property of naringenin in an in vivo system and its mechanisms for live protective effect on the vascular system in diabetes have not been reported. Therefore, this study was designed to assess the beneficial effect of chronic naringenin treatment on improvement of aortic reactivity dysfunction of STZ-diabetic rats and to investigate some underlying mechanisms.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male albino Wistar rats (Pasteur's institute, Tehran, Iran) weighing 210-280 g were housed in an air-conditioned room at 21 ± 2°C, supplied with standard pellet diet and tap water ad libitum. Procedures involving animals and their care were conducted in conformity with NIH guidelines. The experiment protocol was approved by Ethics Committee of Shahed University (Tehran, Iran).

Experimental Protocol

Male diabetic rats (n=32) were divided into control, naringenin-treated control, diabetic, and naringenin-treated diabetic groups. The rats were rendered diabetic by a single intraperitoneal dose of 60 mg kg-1 streptozotocin (STZ) freshly dissolved in ice-cold 0.1 M citrate buffer (pH 4.5). Age-matched normal rats received an equivalent volume of buffer comprised a non-diabetic control group. One week after STZ injection, overnight fasting blood samples were collected and serum glucose concentrations were measured using glucose oxidation method (Zistchimie, Tehran). Only those animals with a serum glucose level higher than 250 mg/dl were selected as diabetic. During the next week, diabetes was reconfirmed by the presence of polyphagia, polydipsia, polyuria, and weight loss. Normal and diabetic rats were divided into four groups of (eight in each): Normal vehicle-treated control, naringenin-treated control, diabetic, and naringenin-treated diabetic. Naringenin was daily administered i.p. at a dose of 10 mg/kg b.w. dissolved in cremophor for five weeks. Dose of naringenin was chosen according to our pilot study and earlier reports.[12] Body weight were regularly recorded before STZ injection and at 3rd and 6th weeks after the study.

After 6 weeks, the rats were anesthetized with diethyl ether, decapitated. The abdomen was opened, descending thoracic aorta was carefully excised and placed in a Petri dish filled with cold Krebs solution. The aorta was cleaned of excess connective tissue and fat, and cut into rings of approximately 4 mm in length. Aortic rings were suspended between the bases of two triangular-shaped wires. One wire was attached to a fixed tissue support in a 50 ml isolated tissue bath containing Krebs solution (pH 7.4) maintained at 37°C and continuously aerated with a mixture of 5% CO2 and 95% O2. The other end of each wire attached by a cotton thread to a F60 isometric force transducer (Narco Biosystems, USA) connected to a computer. Care was taken to avoid damaging the luminal surface of endothelium. Aortic rings were allowed to equilibrate at a resting tension of 1.5 g for at least 45 min. In some experiments, the endothelium was mechanically removed by gently rubbing the internal surface with a filter paper. Isometric contractions were induced by the addition of phenylephrine (PE, 1 μM) and once the contraction was stabilized, acetylcholine (ACh) was added to the bath to attain a concentration of 1 μM in order to assess the endothelial integrity of the preparations. Endothelium was considered to be intact when ACh elicited a vasorelaxation ≥50% of the maximal contraction obtained in vascular rings precontracted with phenylephrine (PE). The absence of acetylcholine relaxant action in the vessels indicated the total removal of endothelial cells. After assessing the integrity of the endothelium, vascular tissues were allowed to recuperate for at least 30 min.

At the end of the equilibration period, dose-response curves with KCl (10-50 mM) and PE (10-9-10-5M) in the presence and absence of endothelium were obtained in aortic rings in a cumulative manner. To evaluate ACh (10-9-10-4M)-induced vasodilatation in rings with endothelium, they were preconstricted with a submaximal concentration of PE (10-6M) which produced 70-80% of maximal response. The sensitivity to the agonists was evaluated as pD2, which is the negative logarithm of the concentration of the drug required to produce 50% of the maximum response.

To determine the participation of nitric oxide (NO), rings were incubated 30 min before the experiment with N (G)-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) (100 μM, a non-selective NOS inhibitor). To determine the participation of endothelial vasodilator factors in response to ACh, segments were incubated with indomethacin (INDO) (10 μM, an inhibitor of cyclooxygenase-derived prostanoid synthesis) 30min before the experiment with ACh.

After each vasoreactivity experiment, aortic rings were blotted, weighed, and the cross-sectional area (csa) was calculated using the following formula: Cross-sectional area (mm2) = weight (mg) × [length (mm) × density (mg mm3-1)]-1. The density of the preparation was regarded as 1.05 mg/mm2.

Drugs

Phenylephrine, naringenin, cremophor, STZ, ACh, INDO, and L-NAME were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO, USA). All other chemicals were purchased from Merck (Germany) and Darupakhsh Co (Iran). Indomethacin solution was prepared in ethanol concentration less than 0.001% (v/v).

Data and Statistical Analysis

All values were given as means ± SEM. Contractile response to PE was expressed as grams of tension per cross-sectional area of tissue. Relaxation response for ACh was expressed as a percentage decrease of the maximum contractile response induced by PE. Statistical analysis was carried out using repeated measure ANOVA and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Body Weight

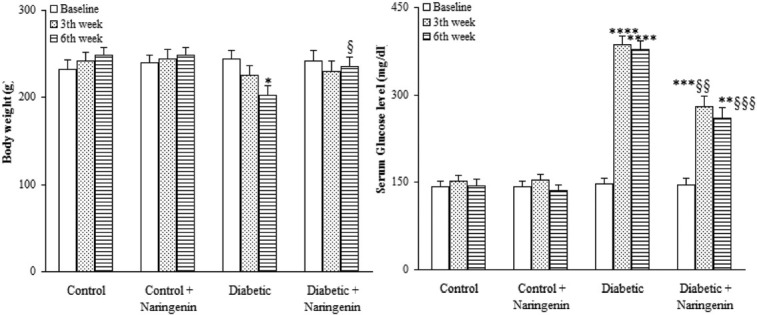

Body weight of the diabetic group was significantly lower versus control group at sixth week after the study (P<0.05) and naringenin-treated diabetic group had a significantly higher body weight as compared to diabetic group (P<0.05) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Comparison of body weight and serum glucose level in diabetic rats treated with naringenin (means ± S.E.M) (n=8). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.005, ****P<0.0005 (as compared to week 0 in the same group) $ P<0.05, $$P<0.01, $$$P<0.005 (vs. Diabetic in the same week).

Serum Glucose Level

Diabetic group had a significantly higher serum glucose level relative to control group at 3rd and 6th weeks after the study (P<0.0005) and treatment of diabetic group with naringenin significantly lowered serum glucose level relative to diabetic group at the same weeks (P<0.01) and 6 (P<0.005), respectively. In addition, naringenin treatment of control rats did not lead to any significant change in this respect [Figure 1].

Vascular Reactivity

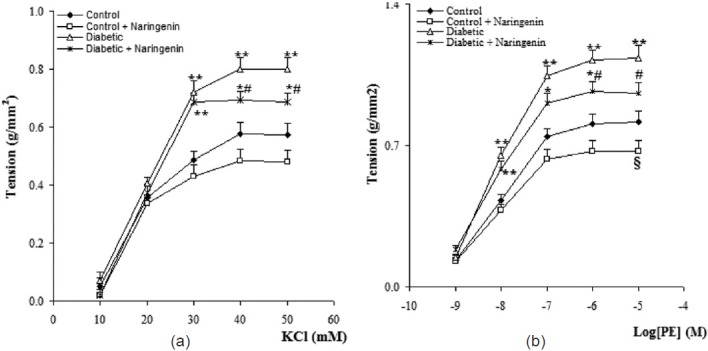

Cumulative addition of KCl (10-50 mM) and PE (10-9-10-5M) resulted in concentration dependent contractions in aortas of all groups [Figure 2]. The maximum contractile responses to KCl and PE in the aorta from vehicle-treated diabetic rats in the presence of endothelium were found to be significantly (P<0.01) greater than vehicle-treated control rats and concentration-response curve of endothelium-intact aortas from naringenin-treated diabetic rats to KCl and PE was significantly attenuated compared to vehicle-treated diabetics (P<0.05). In addition, aortic rings with endothelium from naringenin-treated control group showed a non-significant reduction in contractile response to KCl and a significant reduction in contractile response to PE (P<0.05) as compared to vehicle-treated controls. There were also no significant differences among the groups in terms of the pD2 (data not shown), indicating that there has not been any significant change in the sensitivity of aortic rings from different groups.

Figure 2.

Cumulative concentration-response curves for KCl (a) and phenylephrine (PE) (b) in aortic preparations 6 weeks after experiment (means ± S.E.M). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (As compared to control), #P<0.05 (as compared to diabetic), $ P<0.05 (as compared to control).

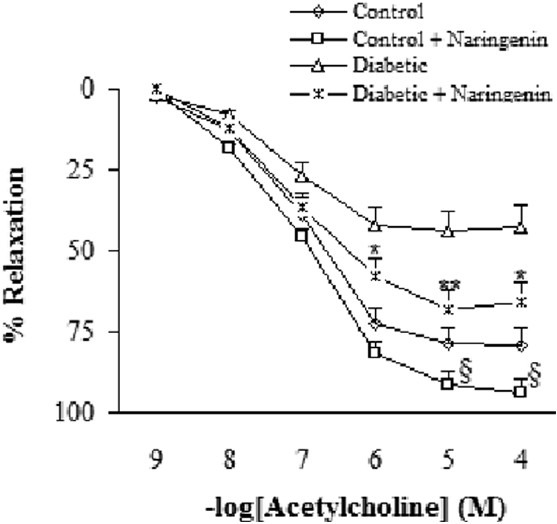

Addition of ACh resulted in concentration-dependent relaxations in all aortic rings precontracted with PE [Figure 3]. Endothelium-dependent relaxation responses induced by ACh was significantly lower in vehicle-treated diabetic rats in relation to vehicle-treated controls (P<0.05-0.005). The existing difference between naringenin-treated and vehicle-treated diabetic rats was only significant (P<0.05-0.01) at concentrations higher than 10-6 M. Relaxation response of naringenin-treated control rats was significantly greater than control group at concentrations higher than 10-5 M (P<0.05).

Figure 3.

Cumulative concentration-response curves for ACh in aortic rings precontracted with PE. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (as compared to diabetic), $ P<0.05 (as compared to control).

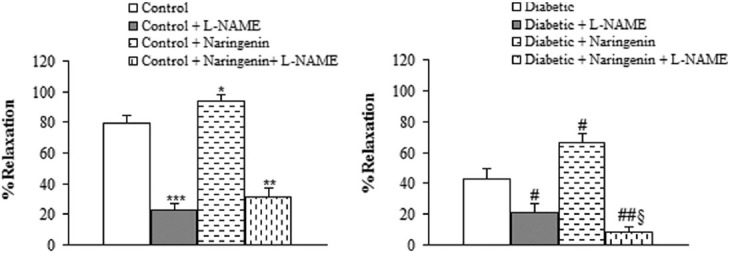

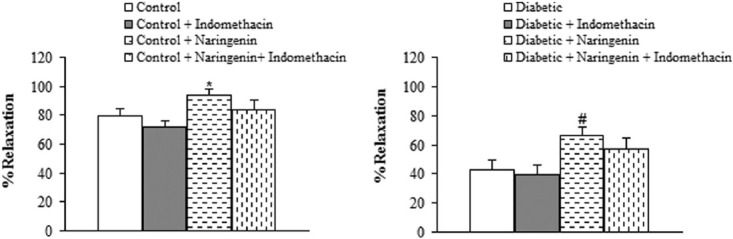

Regarding relaxation response to ACh, pre-incubation of aortic rings with L-NAME almost completely abolished the vasodilator response to ACh in segments from naringenin-treated control and diabetic rats, indicating the important role of endothelium-derived nitric oxide (NO) in the vascular effect of naringenin [Figure 4]. Preincubation of aortic segments from naringenin-treated diabetic rats with INDO non-significantly diminished the endothelial vasodilator response to ACh [Figure 5].

Figure 4.

Maximum relaxation response for ACh in aortic rings precontracted with phenylephrine in the presence and absence of L-NAME. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.005 (vs. control), # P<0.05, ## P<0.01 (vs. diabetic), $ P<0.05 (vs. diabetic + L-NAME).

Figure 5.

Maximum relaxation response for ACh in aortic rings precontracted with phenylephrine in the presence and absence of indomethacin. *P<0.05 (vs. control), # P<0.05 (vs. diabetic).

Discussion

In this study, chronic administration of naringenin had a moderate and significant hypoglycemic effect, it reduced the enhanced contractility of aortic rings to KCl and PE and increased ACh-induced relaxation which was partly due to involvement of NO pathway since the relaxation was blocked in the presence of L-NAME. In the presence of INDO, relaxation response to ACh was non-significantly attenuated.

Vascular dysfunction is one of the complicating features of diabetes in humans and its experimental model and hyperglycemia is the primary cause of micro and macrovascular complications in diabetic condition.[13] Compared to the aortic rings from control animals, contraction of aortas to KCl and PE from diabetic rats significantly increased in our study that was consistent with some previous studies.[14] Impaired endothelial function,[15] enhanced sensitivity of calcium channels,[16] an increase in vasoconstrictor prostanoids due to increased superoxide anions and increased sensitivity to adrenergic agonists[17] might all be responsible for increased contractile responses in diabetic rats, which could have been improved following naringenin treatment. In endothelial cells of most vascular beds, ACh could stimulate production and release of endothelial-derived relaxing factors including NO, prostacyclin and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor and in this way leads to relaxation of vascular smooth muscle in an endothelium-dependent manner.[18–20] The ACh-induced relaxation response is endothelium-dependent and NO-mediated.[14]

The present work reveals that the endothelium-dependent relaxant response reduced in aorta from STZ-induced diabetic rats. Although some researchers asserted that the sensitivity to ACH decreases in diabetes,[17] the results of this research, in accordance with those of many previous ones[21] reveals that diabetes in long-term only decrease the maximum responses to ACh but not the sensitivity (pD2). Impaired endothelium-dependent relaxation in STZ-induced diabetic rat might be due to increased blood glucose level and decreased blood insulin level. It has been shown that hyperglycemia causes tissue damage with several mechanisms, including advanced glycation end product (AGE) formation, increased polyol pathway flux, apoptosis and reactive oxygen species formation.[22]

Our results showed that naringenin treatment could exert a clear and significant hypoglycemic effect in STZ-induced diabetic rats. Therefore, its beneficial effect on aortic tissue of diabetic rats may be in part due to its hypoglycemic effect. In addition, the effect on vascular tissue of diabetic animals is believed to be due to enhanced oxidative stress, as shown by enhanced malondialdehyde (MDA) and decreased activity of defensive enzymes like superoxide dismutase.[23] This could lead to diabetes-induced functional changes in vascular endothelial cells and the development of altered endothelium-dependent vasoreactivity. In the present study, chronic treatment of naringenin may have decreased MDA content and enhanced SOD activity in aortic tissue from diabetic rats, indicating that the improvement in vascular responsiveness from naringenin may be partly due to ameliorating lipid peroxidation and oxidative injury. The latter mechanism warrants further investigation in future studies. In this study, part of vascular beneficial effect of naringenin has been through NO-mediated pathway, because L-NAME pretreatment blocked its effect. In this respect, naringenin could have upregulated the expression of eNOS, indicating the ability of this flavonoid to induce NO synthesis. In support of these ideas, it has been reported that naringenin could reduce oxidative damage and increase NO bioavailability in some metabolic disorders.[24]

In conclusion, in vivo chronic treatment of diabetic rats with naringenin could prevent the functional changes in vascular reactivity in diabetic rats through nitric oxide- and not prostaglandin-dependent pathway. Our data may be helpful in the development of new natural drugs to improve endothelial function and prevent cardiovascular diseases.

Acknowledgment

The results of this study was obtained from MD thesis project, approved and financially supported by Shahed University (Tehran) in 2009. Authors would also like to appreciate Miss Fariba Ansari for her great technical assistance.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Financially supported by Shahed University (Tehran) in 2009

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Coccheri S. Approaches to prevention of cardiovascular complications and events in diabetes mellitus. Drugs. 2007;67:997–1026. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200767070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nasri S, Roghani M, Baluchnejadmojarad T, Rabani T, Balvardi M. Vascular mechanisms of cyanidin-3-glucoside response in streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Pathophysiology. 2011;18:273–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naito M, Fujikura J, Ebihara K, Miyanaga F, Yokoi H, Kusakabe T, et al. Therapeutic impact of leptin on diabetes, diabetic complications, and longevity in insulin-deficient diabetic mice. Diabetes. 2011;60:2265–73. doi: 10.2337/db10-1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stoclet JC, Schini-Kerth V. Dietary flavonoids and human health. Ann Pharm Fr. 2011;69:78–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pharma.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavia-Saiz M, Busto MD, Pilar-Izquierdo MC, Ortega N, Perez-Mateos M, Muniz P. Antioxidant properties, radical scavenging activity and biomolecule protection capacity of flavonoid naringenin and its glycoside naringin: A comparative study. J Sci Food Agric. 2010;90:1238–44. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.3959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi Y, Dai J, Liu H, Li RR, Sun PL, Du Q, et al. Naringenin inhibits allergen-induced airway inflammation and airway responsiveness and inhibits NF-kappaB activity in a murine model of asthma. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;87:729–35. doi: 10.1139/y09-065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qin L, Jin L, Lu L, Lu X, Zhang C, Zhang F, et al. Naringenin reduces lung metastasis in a breast cancer resection model. Protein Cell. 2011;2:507–16. doi: 10.1007/s13238-011-1056-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mulvihill EE, Assini JM, Sutherland BG, DiMattia AS, Khami M, Koppes JB, et al. Naringenin decreases progression of atherosclerosis by improving dyslipidemia in high-fat-fed low-density lipoprotein receptor-null mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:742–8. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.201095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ortiz-Andrade RR, Sanchez-Salgado JC, Navarrete-Vazquez G, Webster SP, Binnie M, Garcia-Jimenez S, et al. Antidiabetic and toxicological evaluations of naringenin in normoglycaemic and NIDDM rat models and its implications on extra-pancreatic glucose regulation. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2008;10:1097–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2008.00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saponara S, Testai L, Iozzi D, Martinotti E, Martelli A, Chericoni S, et al. (+/-)-Naringenin as large conductance Ca (2+)-activated K+ (BKCa) channel opener in vascular smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;149:1013–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orallo F, Camina M, Alvarez E, Basaran H, Lugnier C. Implication of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase inhibition in the vasorelaxant activity of the citrus-fruits flavonoid (+/-)-naringenin. Planta Med. 2005;71:99–107. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-837774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Badary OA, Abdel-Maksoud S, Ahmed WA, Owieda GH. Naringenin attenuates cisplatin nephrotoxicity in rats. Life Sci. 2005;76:2125–35. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madonna R, De Caterina R. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of vascular injury in diabetes-part I: Pathways of vascular disease in diabetes. Vascul Pharmacol. 2011;54:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roghani M, Baluchnejadmojarad T. Chronic epigallocatechin-gallate improves aortic reactivity of diabetic rats: Underlying mechanisms. Vascul Pharmacol. 2009;51:84–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olukman M, Sezer ED, Ulker S, Sozmen EY, Cinar GM. Fenofibrate treatment enhances antioxidant status and attenuates endothelial dysfunction in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Exp Diabetes Res. 2010;2010:828531. doi: 10.1155/2010/828531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang KC, Chung SY, Chong WS, Suh JS, Kim SH, Noh HK, et al. Possible superoxide radical-induced alteration of vascular reactivity in aortas from streptozotocin-treated rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;266:992–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abebe W. Effects of taurine on the reactivity of aortas from diabetic rats. Life Sci. 2008;82:279–89. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang LN, Vincelette J, Chen D, Gless RD, Anandan SK, Rubanyi GM, et al. Inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase attenuates endothelial dysfunction in animal models of diabetes, obesity and hypertension. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;654:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flammer AJ, Luscher TF. Human endothelial dysfunction: EDRFs. Pflugers Arch. 2010;459:1005–13. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0822-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takaki A, Morikawa K, Murayama Y, Yamagishi H, Hosoya M, Ohashi J, et al. Roles of endothelial oxidases in endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor responses in mice. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2008;52:510–7. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e318190358b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silan C. The effects of chronic resveratrol treatment on vascular responsiveness of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Biol Pharm Bull. 2008;31:897–902. doi: 10.1248/bpb.31.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartge MM, Unger T, Kintscher U. The endothelium and vascular inflammation in diabetes. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2007;4:84–8. doi: 10.3132/dvdr.2007.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baluchnejadmojarad T, Roghani M. Chronic administration of genistein improves aortic reactivity of streptozotocin-diabetic rats: Mode of action. Vascul Pharmacol. 2008;49:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kannappan S, Palanisamy N, Anuradha CV. Suppression of hepatic oxidative events and regulation of eNOS expression in the liver by naringenin in fructose-administered rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;645:177–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]