INTRODUCTION

The awareness and attitudes towards labour pain and labour pain relief in antenatal women are not clearly known, particularly in developing countries. Childbirth, however fulfilling, is a painful experience for the majority of women.[1,2] Various pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods of labour analgesia are available. This survey was carried out to assess the women's awareness and attitudes towards labor pain and labor pain relief.

METHODS

The survey was conducted in the antenatal clinic of a 30-bedded private hospital in Chennai, India. After institutional approval and informed consent, the prepared questionnaire was handed to the women to be filled up while waiting for the antenatal check-up. Two hundred questionnaires were handed out, 109 were returned and 100 had answered most of the questions.

RESULTS

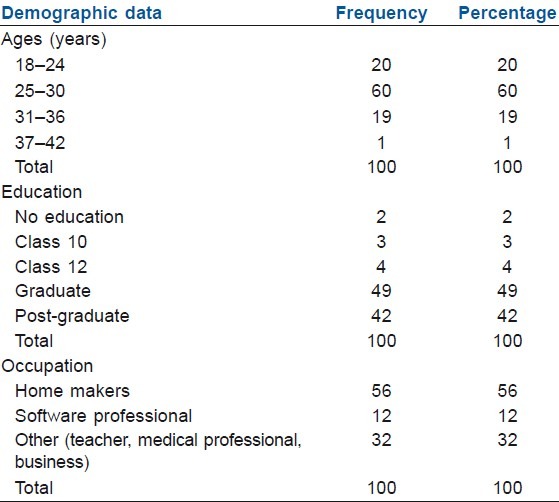

The demographic data are presented in Table 1. The median age was 27.39 years. Almost all of the women (98/100) were educated (completed a minimum of study up to class 10 or more). Half of the women were home makers (56/100, 56%). Most of the women were primiparous (63/100, 63%).

Table 1.

Demographic data

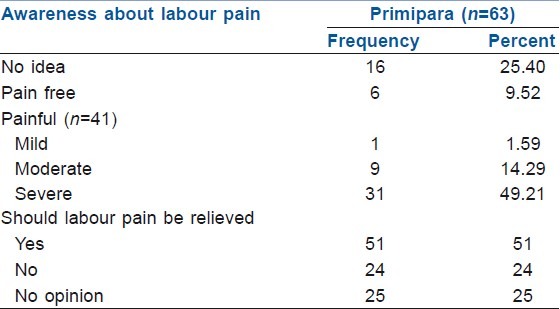

The primiparous women were assessed for their expectations about labour pain. Forty-one (41/63, 65.08%) expected to experience some degree of pain during labour [Table 2].

Table 2.

Awareness of nature of labour pain and attitude towards labour pain

Fifty-one women (51/100, 51%) felt that labour pain should be relieved [Table 2]. Reasons to opt for pain relief were: To relieve pain (n=7), to relieve stress (n=5), to feel confident (n=2), to enjoy the experience (n=3) and better assessment of the baby (n=1).

Some (24/100, 24%) felt that labour pain should not be relieved and a few of them gave the following reasons: It is a natural process (n=7), to be able to push the baby (n=2), no pain no gain (n=3) and it may lead to some other problem (n=1). The rest (25/100, 25%) had no opinion on whether labour pain should be relieved.

Only 23% of the women (23/100) planned to ask for pain relief during the forthcoming delivery. Thirty-six percent of the women (36/100) did not intend to use any labour pain relief and 10% (10/100) wanted to have more information before they made a decision.

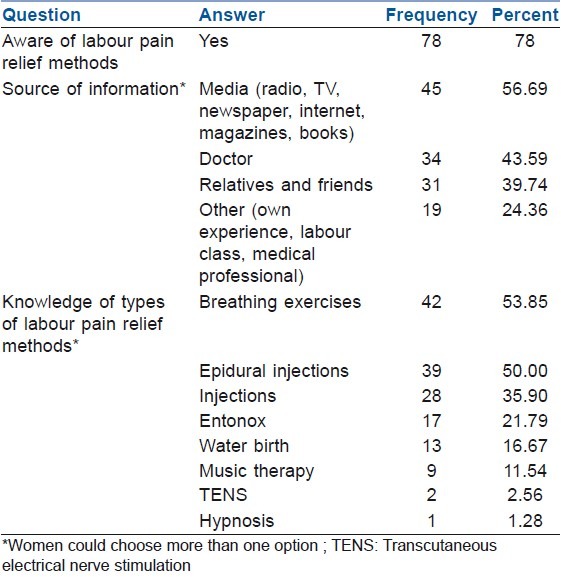

Most of the women (78/100, 78%) had heard about methods to relieve labour pain mainly through the media and through their doctor [Table 3], but the majority (65/78, 83.33%) had no idea which method is useful. The rest (13/78, 16.67%) chose epidural injection, breathing exercises, injections, entonox and music therapy as useful methods.

Table 3.

Knowledge about labour pain relief methods

Thirty-six women (36/78, 46.15%) had concerns relating to the relief of labour pain. Their concerns were baby related (20/36, 55.56%) (baby may be affected, mother-baby bonding may be affected), labour related (n=14/36, 38.89%) (contractions may be unnatural, inability to push or use lower body parts, may lead to caesarean section or instrument use, labour may be unnatural) and/or pain relief method related (n=23/36,63.89%) (method may not work, back ache).

DISCUSSION

Two-thirds of the primiparas were aware that labour is painful. Uterine contractions, cervical dilatation and stretching of the lower uterine segment are responsible for pain during the first stage of labour. Visceral afferent C-type fibres accompanying the sympathetic nerves carry the pain impulses and enter the spinal cord at the T10-L1 levels. In the second stage of labour, somatic afferent fibres from the vagina and perineum convey pain impulses in the pudendal nerves to the S2-S4 spinal nerve roots.[1,2]

Half the participants were in favour of labour pain being relieved but very few (18/51, 35.29%) could guess the beneficial effects of relieving pain and stress. This lack of knowledge is further confirmed by the poor response for plans to use labour analgesia (23/100, 23%). Labour pain results in the stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system leading to maternal hypertension and reduced uteroplacental blood flow. During labour, the woman may also hyperventilate, leading to leftward shift of the maternal oxygen–haemoglobin dissociation curve and a consequential reduction in the foetal arterial oxygen tension. Relief of pain and anxiety during labour may benefit the mother and foetus by decreasing maternal hyperventilation and catecholamine secretion.[2]

The women in our survey are better informed than antenatal women in Nairobi, South Africa and Nigeria that labour pain can be relieved. However, their level of knowledge is similarly low.[3–6] There are many methods to relieve labour pain. The pharmacological methods known are parenteral opioids, epidural analgesia, nitrous oxide and paracervical block.[1,7] Some of the non-pharmacological methods are breathing exercises, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, sterile water injections, acupressure, acupuncture, hydrotherapy, immersion bath, audio-analgesia, aromatherapy, hypnosis, labour support, massage and relaxation.[8,9] The ideal labour pain relief method must be safe and effective, and should not interfere with labour or the mobility of the parturient.[1] Only 36 women had any such concerns.

Our survey had only 100 participants and did not study the effect of religion, age, parity or education on the awareness and attitudes to labour pain and labour pain relief.

There are no Indian studies to determine these issues. Further studies are necessary to ascertain and compare awareness and attitudes towards labour pain and labour pain relief in rural areas as opposed to urban areas, as also among men and non-pregnant women. The timing, best method and benefits of educating the antenatal woman also need to be determined in the Indian context.[4,10,11] Clinical studies may also be required to determine the most cost-effective method. Based on the information gained, necessary changes may be made in patient care and health policy.

CONCLUSION

This descriptive study revealed that there is sufficient awareness that labour is painful and that there are ways to relieve labour pain. However, there is a lack of knowledge regarding the need for pain relief during labour, the various types of labour pain relief methods and their advantages and disadvantages.

Antenatal women should be educated about the need for labour pain relief and the available options. This may be done at an appropriate time during the antenatal visits by the obstetrician or Anaesthetist. The pregnant women's knowledge may also be improved by the provision of information leaflets, labour pain websites and childbirth preparation classes.

REFERENCES

- 1.Findley I, Chamberlain G. ABC of labor care. Relief of pain. BMJ. 1999;318:927–30. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7188.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferne RB, Barbara MS, Cynthia AW, Alan CS. Obstetrical Anesthesia. In: Paul GB, editor. Clinical Anesthesia. 6th ed. New Delhi: Wolters Kluwer (India) Pvt. Ltd; 2009. pp. 1142–5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mung’ayi V, Nekyon D, Karuga R. Knowledge, attitude and use of labour pain relief methods among women attending antenatal clinic in Nairobi. East Afr Med J. 2008;85:438–41. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v85i9.117084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mugambe JM, Nel M, Hiemstra LA, Steinberg WJ. Knowledge and attitude toward pain relief during labour of women attending the antenatal clinic of Cecilia Makiwane Hospital, South Africa. SA Fam Pract. 2007;49:16–24. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ibach F, Dyer RA, Fawcus S, Dyer SJ. Knowledge and expectations of labour among primigravid women in the public health sector. S Afr Med J. 2007;97:461–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olayemi O, Aimakhu CO, Udoh ES. Attitudes of patients to obstetric analgesia at the University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;23:38–40. doi: 10.1080/0144361021000043209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leeman L, Fontaine P, King V, Klein MC, Ratcliffe S. The nature and management of labor pain: Part II. Pharmacologic pain relief. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:1115–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown ST, Douglas C, Flood LP. Women's evaluation of intrapartum nonpharmacological pain relief methods used during labor. J Perinat Educ. 2001;10:1–8. doi: 10.1624/105812401X88273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tournaire M, Theau-Yonneau A. Complementary and Alternative Approaches to Pain Relief During Labor. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2007;4:409–17. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raynes-Greenow CH, Roberts CL, McCaffery K, Clarke J. Knowledge and decision-making for labour analgesia of Australian primiparous women. Midwifery. 2007;23:139–45. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stewart A, Sodhi V, Harper N, Yentis SM. Assessment of the effect upon maternal knowledge of an information leaflet about pain relief in labour. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:1015–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2003.03360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]