Abstract

Background:

Identifying the molecular mechanisms of intrinsic aging is critical in developing modalities for reversal of cutaneous aging.

Objective:

The objective was to evaluate the expression of epidermal Fas, epidermal thickness, collagen, and elastic fibers degeneration in unexposed skin of aged individuals compared with young ones.

Materials and Methods:

Skin biopsies were taken from normal skin of the back of 22 old subjects (age range: 48-75 years) and 15 young subjects (age range: 18-28 years). Skin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, Masson trichrome, orcein. Epidermal thickness was measured with image analyzer and scoring was done for collagen and elastic fiber degeneration. Fas immunostaining was done. Quantitative and qualitative data were compared statistically between the old and young subjects.

Results:

A statistically significant decreased epidermal thickness was found in old compared with young skin (P<0.05). A statistically significant number of patients showed decreased epidermal thickness, density, and fragmentation of both collagen and elastic fibers in old compared with young skin (P<0.001). Epidermal Fas expression was detected in 19 of 22 old subjects (86.4%) compared with 2 of 15 young subjects (13.3%) (P<0.001). There was no statistically significant correlation between age of old subjects and each of epidermal thickness, collagen, and elastic fiber degeneration.

Conclusion:

The decreased epidermal thickness and morphological alteration of collagen and elastic fibers are not correlated with aging and Fas-mediated apoptosis could be involved in thinning of the epidermis in unexposed aged skin.

Keywords: Fas aging, immunohistochemistry, collagen fibres, morphometry, elastic fibres

Introduction

Aging is affected by a genetic program as well as by cumulative environmental and endogenous insults that take place throughout the organism's life span.[1] There are two main processes that induce skin aging; intrinsic (chronological aging) in sun protected skin and extrinsic (photoaging) in sun-exposed areas. Intrinsic aging reflects the genetic background and depends on time.[2] Understanding the aging process is important, because the proportion of individuals 55 years or older is continuously increasing. It is predicted to be 31% in the USA in the year 2030 with similar demographic shifts predicted for Europe and Japan.[1] To effectively manage skin diseases of the elderly and to use the proper intervention modalities to reverse cutaneous aging, it is important to be familiar with the clinical and histological changes that accompany skin aging.[3] Understanding the molecular mechanisms of aging may open new strategies in dealing with various diseases accompanying aging.[4]

The most noticed morphological modification of skin aging in sun-protected areas (intrinsic aging) is the progressive loss of skin tissue. This loss of skin tissue can be attributed to several factors such as loss of cells. Cell loss concerns both the epidermal and dermal layers[5] and decreased cell proliferation.[6] In self-renewing tissue like the epidermis, cell numbers are tightly regulated by a delicate balance between proliferation, terminal differentiation and apoptosis.[7] Dysfunction of any one of these processes can result in either uncontrolled cell growth or uncontrolled cell death.[8] Many reports have demonstrated that apoptosis is among the most important molecular processes involved in skin aging.[4,9] Apoptosis, which is often equated with programmed cell death, is a physiological form of cell death that is responsible for the deletion of cells. Initiation of apoptosis occurs principally by signals from two distinct but convergent pathways; the intrinsic, or mitochondrial, pathway and the extrinsic, or receptor-initiated, pathway.[10] Death receptors (DRs) are a family of membrane receptors, also named tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNF-R), that transduce pro-apoptotic signals from the extracellular space into the intracellular milieu.[11] Fas is a member of the DRs (also referred to as CD95 or APO- 1). It is a 48-kDa 319 amino acids member of the TNF\nerve growth factor receptor family[12]). Its main function is the induction of apoptosis in many cell types including human keratinocytes.[13] Triggering of CD95 molecules (Fas) either by agonist antibodies or by the natural ligand CD95L (FasL) induces apoptosis.[14] In normal epidermis, Fas is expressed by basal and suprabasal keratinocytes.[15]

The aim of this study was to determine the role of a Fas (CD95) molecule in changes of human epidermis, collagen, and elastic fibers of human dermis in sun-protected nondiseased skin of aged subjects, compared with young controls.

Materials and Methods

This study included 37 patients, 22 represented the old group (age range 48-75 years); 9 males and 13 females. 15 represented the young group (age range 18-28 years); 10 males and 5 females. Smokers, obese subjects, patients with diabetes, malignancy were excluded from the study.

All patients underwent surgical procedures in plastic surgery (Air Force Military Hospital, Dar El- Shefa Hospital and Manshiat El- Bakery Hospital, Cairo, Egypt). A written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Methods

Skin biopsy specimens

One centimeter normal skin specimen was taken from the back. All specimens were fixed in neutral buffered formalin (PH7.2), processed, paraffin embedded blocks were prepared and sections were put on adhesive slides. Hematoxylin and eosin stained sections were used for routine histopathological examinations.

Morphometric analysis

Histological assessment was performed by routine light microscopy of the histological preparation. Measurement of the epidermal thickness (morphometry) was carried out in the vertical plane with an image analyzer optical micrometer (Image-G, 1036, USA) in the Pathology Department, Faculty of Medicine for Girls, Al-Azhar University. Measurements were taken at a minimum of 10 points along the epidermis and the mean±standard deviation (SD) was calculated.

Assessment of collagen fibers degeneration

Sections were stained with Masson trichrome stain.[16] Histological assessment was performed by routine light microscopy of the histological preparation. Scoring of collagen bundles was done as follows:

0 = Thick and/or rich blue collagen bundles

1 = Moderate thickness collagen bundles

2 = Thin, loose, and \or fragmented collagen bundles.

Assessment of elastic fiber degeneration

Sections were stained with Orcein stain.[16] Histological assessment was performed by routine light microscopy of the histological preparation. Scoring of elastic fibers was done as follows:

0 = Rich elastic fibers

1 = Moderate thickness elastic fibers

2 = Thin, short, loose, and fragmented elastic fibers.

Fas immunostaining

Sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and incubated in hydrogen peroxide block for 10-15 minutes to reduce nonspecific background staining due to endogenous peroxidase and sections were washed two times in the buffer. Sections were incubated in digestive enzymes, washed four times in the buffer. Monoclonal mouse anti-Fas (APO-1) antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific Laboratories, Fremont, USA) was applied to the sections and then incubated and washed four times in the buffer. Biotinylated goat antipolyvalent was applied to sections and incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature and washed four times in the buffer. Streptavidin peroxidase was applied to sections and incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature, and rinsed four times in the buffer. One drop (40 μl) DAB Plus Chromogen and 2 ml of DAB plus substrate were mixed by swirling and were applied to the sections, and the sections were incubated for 5-15 minutes. Finally, permanent mounting media sections were counterstained and coverslip was put.

Statistical analysis

Data were coded and entered using the statistical package SPSS version 15 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Data were summarized using range and mean±standard deviation (SD) for quantitative variables and numbers and percentages for qualitative variables. Comparison between groups were done using a chi-square test for qualitative variables. Independent sample t-test was used for normally distributed quantitative variables. Pearson's correlation co-efficient (r) test was used to test for linear correlation between quantitative variables. P≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

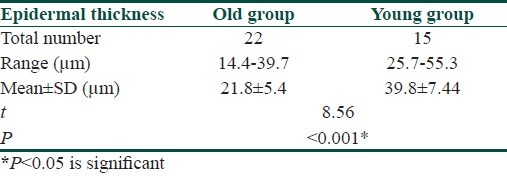

A significant difference (P<0.05) was found between the mean epidermal thickness of old group skin (21.81±5.4 μm) and that of the young group skin (39.84±7.4 μm) [Table 1, Figure 1].

Table 1.

Comparison between thickness of the epidermis of old and young groups

Figure 1.

(a) Young skin showing normal epidermis and dermis with the mean epidermal measurement of 37.4±7 μm. (b) Aged skin showing thinning of the epidermis and flattening of the dermoepidermal junction with the mean epidermal measurement of 17.6±8 μm (H and E, ×100)

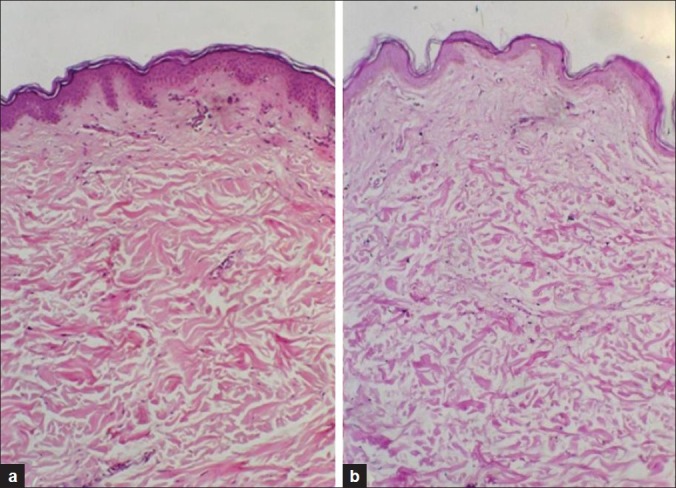

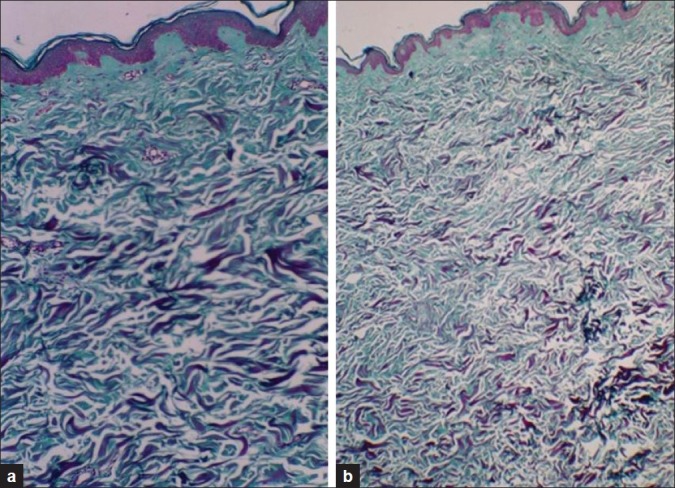

Masson trichrome staining revealed that in the old group, thin, loose, and/or fragmented collagen bundles (score 2) were found in 17 of 22 old subjects (77.3%), moderate thickness collagen bundles (score 1) were found in 1 of 22 old subjects (4.5%). Thick and/or rich blue collagen bundles (score 0) were found in 4 of 22 old subjects (18.2%). In the young group, thick and/or rich blue collagen bundles (score 0) were noted in 11 subjects (73.3%). Moderate thickness collagen bundles (score 1) were found in 4 of 15 young subjects (26.7%). Thin, fine, loose, and/or fragmented collagen bundles (score 2) were not found in the young group [Table 2, Figure 2].

Table 2.

Comparison between Masson trichrome staining of collagen fibers of the old versus young groups

Figure 2.

(a) Biopsy of young skin showing thick bundles of collagen bundles. (b) Biopsy of aged skin showing thin and loose collagen fibers (Masson-Trichrome ×100)

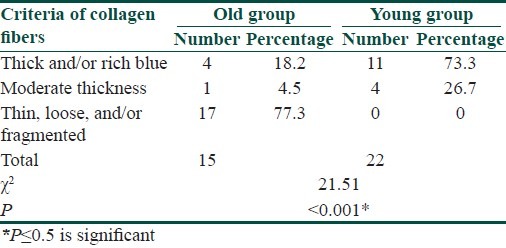

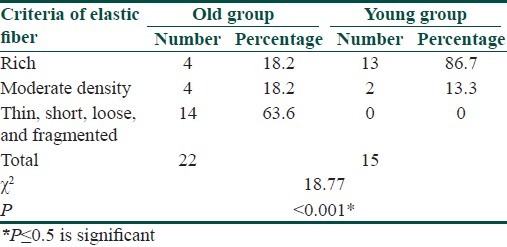

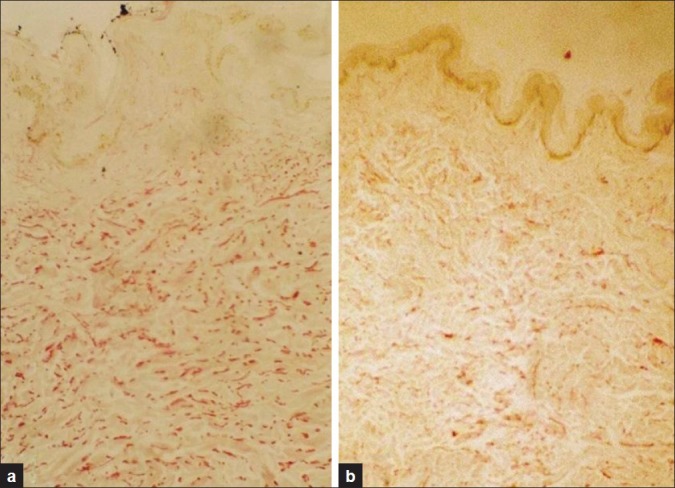

Orcein staining for elastic fibres elicited thin, short, loose, and fragmented elastic fibers (score 2) in 14 of 22 old subjects (63.6%), moderately thickened fibers (score 1) were noticed in 4 of 22 old subjects (18.2%), rich elastic fibers (score 0) were found in 4 of 22 old subjects (18.2%) in papillary, mid, and reticular dermis. Degenerative changes of elastic fibers were most pronounced in the upper than reticular dermis. In the young group, rich elastic fibers (score 0) were noted in 13 of the 15 subjects (87.7%), moderately thickened fibers (score 1) were noted in 2 of 15 subjects (13.3%). No thin short loose and fragmented elastic fibers (score 2) were noticed in the young group [Table 3, Figure 3].

Table 3.

Comparison between Orcein staining of elastic fibers of the old and young groups

Figure 3.

(a) Section from young skin showing high content of elastic fibers in the dermis. (b) Section from old skin showing thin, short, loose, and fragmented elastic fibers (Orcein ×100)

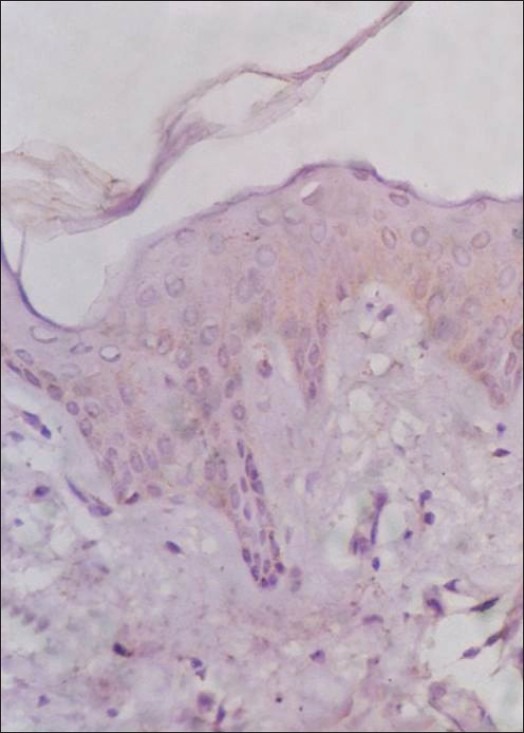

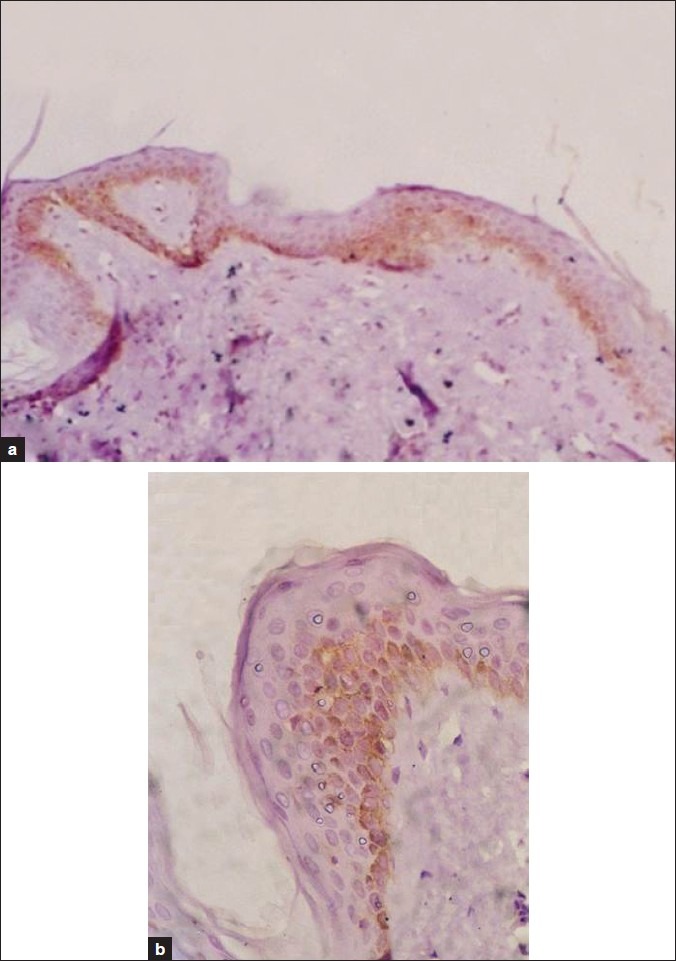

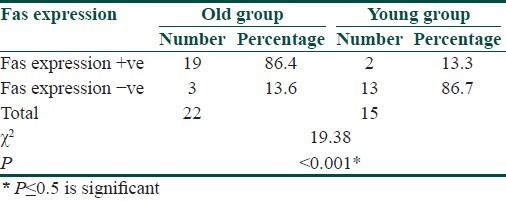

Immunohistochemical staining for Fas expression of the epidermis revealed increased Fas expression in the epidermal keratinocytes below the granular layer of the old group compared with that of the young group [Figures 4 and 5]. Fas expression was positive in 19 of 22 old subjects (86.4%) compared to 2 of the 15 young subjects (13.3%) [Table 4].

Figure 4.

Young skin immunostained for FAS; negative expression of the epitope (FAS immunostain counterstained by H and E, ×200)

Figure 5a, b.

Aged skin immunostained for FAS; expression of the epitope is mainly in the basal keratinocytes (FAS immunostain counterstained by H and E, ×100 and 200)

Table 4.

Comparison between Fas expression in the epidermis of old and young groups

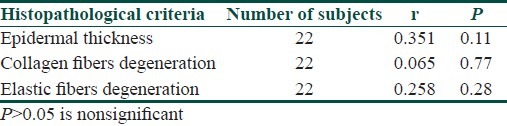

Correlation between age of old subjects and each of epidermal thickness, thickness of collagen fibers or elastic fibers was nonsignificant [Table 5].

Table 5.

Correlation between age of the old subjects and each of epidermal thickness, collagen, and elastic fibers degeneration

Discussion

In the present study, specimens of normal skin were obtained from normal unexposed areas of the back of 22 old subjects with age range of 48-75 years as the old group and 15 young subjects with age range of 18-28 years as the young group as Yaar and Gilchrest[17] mentioned that decline in skin and aging start at age 40 years.

The current study demonstrated that the mean epidermal thickness of the old group is significantly decreased (21.81±5.4 μm) compared with the young group (39.84±7.4 μm). Similar finding was reported by Yaar and Gilchrest[18] and Gilhar et al.[19] who stated that human epidermis showed decreased epidermal thickness in aged versus young skin. This is in contrast with another study[20] that showed that the mean epidermal thickness remained constant throughout different decades whether in sun-exposed or sun-protected skin; however, the epidermis is always significantly thicker in sun-exposed than in sun-protected skin. Yaar and Gilchrest[18] stated that in sun-exposed areas, individuals with skin types III-V show an irregular epidermal thickness.

The current study showed changes in the collagen and elastic fibers in skin of the old group versus young group. Masson trichrome staining for collagen showed thin, loose, fine, and fragmented collagen bundles in 17 out of 22 old subjects (77.3%). Moderate thickness collagen bundles were noticed in 1 out of 22 old subjects (4.5%). Thick, rich blue collagen bundles were noticed in 4 out of 22 old subjects (18.2%) while the young group showed thick and/or rich blue collagen bundles in 11 out of 15 young subjects (73.3%). Moderate thickness collagen bundles were noticed in 4 out of 15 young subjects (26.7%). Thin, fine, and/or loose collagen bundles were not found in any of the young subjects. These results supported the study done by El-Domyati et al.[20] where they demonstrated quantitative as well as qualitative changes in the collagen fibers through different decades. There is a gradual reduction in the amount of collagen fibers in the protected skin particularly in the eighth decade. In 2008, Uitto[21] reported that the intrinsic aging has a dramatic effect on the network of collagen fibers of human skin. Naturally aged skin shows loss of collagen due to increased MMP-1 expression, in addition to the lower levels of collagen synthesized by aged fibroblasts.[22] Mammone et al.[23] reported increased apoptosis in senescent fibroblasts.

Staining with Orcein to identify the changes of elastic fibers with aging revealed, thin, short, and fragmented elastic bundles in 14 out of 22 old subjects (63.6%). Moderate thickness fibers were noticed in 4 out of 22 old patients (18.2%). Rich elastic fibers in papillary and reticular dermis were noticed in 4 out of 22 old patients (18.2%). On the other hand, the young group showed rich elastic fibers in 13 out of 15 young subjects (87.7%) and moderately thickened fibers were noticed in 2 out of 15 young subjects (13.3%). Thin, short, loose, and fragmented elastic bundles were not found in any of the young subjects. These results were in agreement with Uitto[21] who showed that in naturally aged skin there is a clear degeneration of the elastic fibers network. Similar finding was reported by El-Domyati et al.[20] who found that in sun-protected skin, the transverse layer of elastic fibers gradually thinned out with age and also the amount of elastin significantly decreases with age. In exposed skin, quantitative as well as qualitative changes in the elastic and collagen fibers through different decades were reported in sun exposed areas. There is a gradual accumulation of elastin accompanied by a gradual reduction in the amount of collagen fibers. Accordingly, the areas of absent collagen staining in the dermis correlate well with the sites occupied by the deposited elastotic material.[20]

In the present study, correlation between age in the old skin group and each of epidermal thickness, collagen, and/or elastic fibers degeneration was not significant. This absence of correlation could be due to the multiple factors such as hormonal, genetic, and nutritional that can influence dramatically the intrinsic rate of skin aging in any individual.[24] In this study, the relation between sex in the old skin group and thickness of collagen and/or elastic fibers was not significant. This was also reported by Quaglino et al.[25] who found no difference between males and females after 50 years of age in collagen and elastic fibers. Struck[26] suggested that other exogenous factors such as nutrition, immobilization, activity, and adaptive mechanisms influence the biomechanical properties of connective tissue during aging. This is in contrast with a study carried out by Dong et al.[27] who found that during the menopausal years, the loss of estrogen production accelerates skin changes. Collagen and elastin impart strength and resilience to skin, and their degeneration with aging causes skin to become fragile, and aged in appearance. The abrupt estrogen level reduction in postmenopausal women may accelerate age-dependent reduced collagen synthesis, leading to greater collagen deficiency in elderly women than in men.

Immunohistochemical staining for Fas was carried out to detect Fas expression in the epidermis. The results of the current study revealed that the epidermis of the old group showed a significantly greater Fas expression than that of the young group. Nineteen patients out of 22 of old patients (86.4%) showed positive Fas expression. Fas expression was positive in 2 subjects out of 15 of young patients (13.3%). Fas expression was scattered through the basal and spinous layers. This is in accordance with a study done by Gilhar et al.[19] who confirmed that Fas expression of epidermal keratinocytes was elevated in aged relative to young epidermis. They stated that in aged epidermis, Fas expression was not located within the granular layer but scattered throughout the basal and spinous layers in a similar distribution to the apoptotic TUNEL-positive cells while TUNEL-positive keratinocytes, which occur at the granular layer as part of keratinocyte terminal differentiation, do not appear to be related to Fas. This could be given the following explanation: keratinocyte terminal differentiation differs from apoptosis. Pro-grammed cell death occurs during the terminal differentiation of keratinocytes, a phenomenon known as cornification. Although sharing common features including caspase-3 activation, activation of endonucleases, and degradation of DNA and result in cells positive for the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end labeling (TUNEL) reaction but cornification and apoptosis are thought to be two distinct mecha-nisms in the epidermis[28] and there is no evidence for a role of DRs in the formation of the stratum corneum. Moreover, there exists indi-rect evidence that DRs do not play a major role in keratinocyte differentiation because mice deficient for Fas (Ipr/lpr), FasL (gld/gld) or TRAIL exhibit normal skin and in humans; no sign of impaired formation of the stratum corneum has been observed in pa-tients with lymphoproliferative syndromes caused by Fas or FasL mutations,[15] so in young epidermis, keratinocytes with DNA strand breaks (TUNEL-positive) are limited to the granular layer, where they represent part of normal terminal differentiation, are distinct from apoptosis. In contrast, TUNEL-positive cells in aged epidermis were found not only within the granular layer, but scattered throughout the whole epidermis. TUNEL-positive keratinocytes below the granular layer are associated with apoptosis. Apoptosis of keratinocytes in the basal and spinous layers, combined with the impaired cell proliferation of the basal layer, may lead to the decreased overall thickness of the aged epidermis.[19]

According to the results of the current study we conclude that the decreased epidermal thickness and morphological alteration of collagen and elastic fibers are not correlated with the age and Fas-mediated apoptosis could be involved in thinning of the epidermis in unexposed aged skin.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Smith ES, Fleisher AB, Jr, Feldman SR. Demographics of aging and skin disease. Clin. Geriatr Med. 2001;17:631–41. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0690(05)70090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Puizina-Ivi N. Skin aging. Acta Dermato Venereol APA. 2008;17:47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilchrest B, Krutmann G. Skin aging. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlage; 2006. pp. 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Makrantonaki E, Zouboulis C. Molecular mechanisms of skin aging - state of the art. Ann NY Sci. 2007;1119:40–50. doi: 10.1196/annals.1404.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robert L, Labat-Robert J, Robert AM. Physiology of skin aging. Pathol Biol. 2009;57:336–41. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Racquet C, Bonte F. Molecular aspects of skin aging-recent data. Acta Dermatol. 2002;11:1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reefman E, Limbur P, Kallenberg G, Bijl M. Apoptosis in human skin role in pathogenesis of various diseases and relevance for therapy. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005;1051:52–63. doi: 10.1196/annals.1361.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhivotovsky B, Orrenius S. Clinical perspectives of cell death: Where we are and where to go? Apoptosis. 2009;14:333–5. doi: 10.1007/s10495-009-0326-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soroka Y, Ma’or AZ, Leshem AY, Verochovsky LA, Neuman RC, François Menahem Brégégère FA, et al. Aged keratinocyte phenotyping: Morphology, biochemical markers and effects of Dead Sea minerals. Exp Gerontol. 2008;43:947–57. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cotran C, Kumar V, Collins T. Cellular pathology 1: Cell injury and cell death. In: Kumar V, Fausto N, Abbas A, editors. Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease. 7th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders and Co; 2005. pp. 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen G, Goeddel D. TNF-R1 signaling: A beautiful pathway. Science. 2002;296:1634. doi: 10.1126/science.1071924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maher S, Toomey D, Condron, Bouchier-Hoyes D. The controversial role of Fas and Fas ligand in immune privilege and tumour counterattack. J Immunol Cell Biol. 2002;80:131–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2002.01068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sung K, Paik E, Jang K, Suh H, Choi J. Apoptosis is induced by anti-Fas antibody alone in cultured human keratinocytes. J Dermatol. 1997;24:427–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1997.tb02816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suda T, Takahashi T, Golstein P, Nagata S. Molecular cloning and expression of the Fas ligand: A novel member of the tumor necrosis factor family. Cell. 1993;75:1169–78. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90326-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Contassot E, Gaide O, French L. Death receptors and apoptosis. Dermatol Clin. 2007;5:487–501. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Druby R, Wallington E. In: Carleton histological technique. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1980. Connective tissue fibers; pp. 183–94. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yaar M, Gilchrest BA. Skin aging postulated mechanisms and consequent changes in structure and function. Clin Geriatr Med. 2001;4:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0690(05)70089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yaar M, Gilchrest BA. Aging of skin. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz S, editors. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. Vol. 2. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2003. pp. 1386–98. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilhar A, Ullmanny Y, Karry R, Shaalaginov R, Assy B, Serafimovich S, et al. Aging of human epidermis: The role of apoptosis, Fas and telomerase. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:56–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Domyati M, Attia S, Salah F, Brown D, Brik DE, Gasparro F, et al. Intrinsic aging vs. photoaging: A comparative histopathological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study of skin. Exp Dermatol. 2002;11:398–405. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2002.110502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uitto J. The role of elastin and collagen in cutaneous aging: intrinsic aging versus photoexposure. J Drug Dermatol. 2008;7:s12–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varani J, Warner RL, Gharaee-Kermani M, Phan SH, Kang S, Chung JH, et al. Vitamin A antagonizes decrease cell growth and elevated collagen-degrading matrix metaloproteinases and stimulates collagen accumulation in naturally aged human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;114:480–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mammone T, Gan D, Reyhaneh F. Apoptotic cell death increases with senescence in normal human dermal fibroblast cultures. Cell Biol Int. 2006;30:903–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farage AM, Miller W, Elsner P, Maibach HI. Intrinsic and extrinsic factors in skin aging: A review. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2008;30:87–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2494.2007.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quaglino DJ, Bergamini G, Boraldi F, Pasquali-Ronchetti I. Ultrastructural and morphometrical evaluations on normal human dermal connective tissue - the influence of age, sex and body region. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:1013–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Struck HJ. Biomechanics and aging. Gerontology. 1991;24:121–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong SE, Young LJ, Lee S, Sun KM, Gon LB, Seoup CI, et al. Topical application of 17β-estradiol increases extracellular matrix protein synthesis by stimulating TGF-β signaling in aged human skin in vivo. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:1149–61. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Candi E, Schmidt R, Melino G. The cornified enve-lope: A model of cell death in the skin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:328–40. doi: 10.1038/nrm1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]