Abstract

Context:

Every medical practitioner should strive to contribute to the generation of evidence by conducting research. For carrying out research, adequate knowledge, practical skills, and development of the right attitude are crucial. A literature review shows that data regarding knowledge, attitude, and practices toward medical research, among resident doctors in India, is lacking.

Aims:

This study was conducted to assess research-related knowledge, attitude, and practices among resident doctors.

Settings and Design:

A cross-sectional survey was conducted using a pretested, structured, and pre-validated questionnaire.

Materials and Methods:

With approval of the Institutional Ethics Committee and a verbal consent, a cross-sectional survey among 100 resident doctors pursuing their second and third years in the MD and MS courses was conducted using a structured and pre-validated questionnaire.

Statistical Analysis:

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the results.

Results:

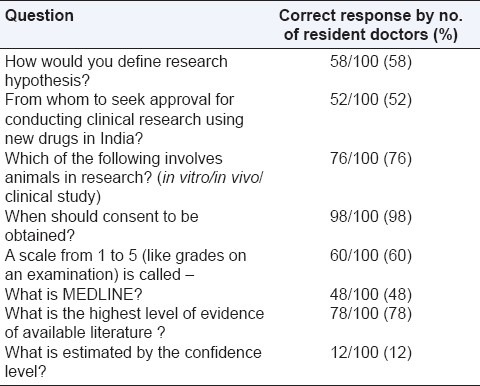

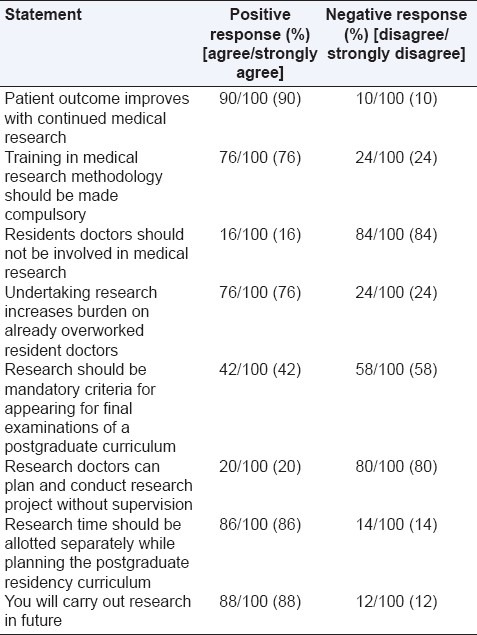

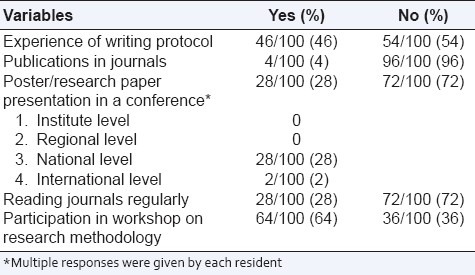

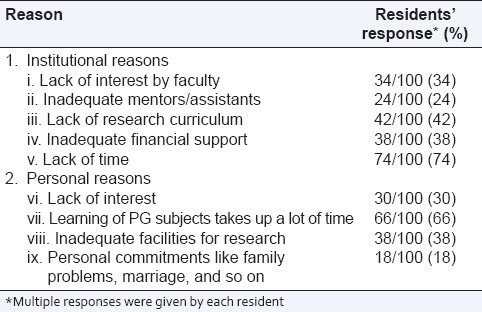

The concept of research hypothesis was known to 58% of the residents. Ninety-eight percent of the residents were aware of the procedure to obtain informed consent. Seventy-six percent agreed that research training should be mandatory. Although 88% of the residents were interested in conducting research in future, 50% had participated in research other than a dissertation project, 28% had made scientific presentations, and only 4% had publications. Lack of time (74%), lack of research curriculum (42%), and inadequate facilities (38%) were stated as major obstacles for pursuing research.

Conclusions:

Although resident doctors demonstrated a fairly good knowledge and positive attitude toward research, it did not translate into practice for most of them. There is a need to improve the existing medical education system to foster research culture among resident doctors

Keywords: Attitude, knowledge, postgraduate student, practice, research, residency curriculum

INTRODUCTION

It is the duty of every doctor to care for his patients and provide the best available treatment. The duty of care also requires doctors to keep their medical knowledge and training up-to-date. Doctors should provide effective treatments based on the ‘best available evidence’. It is widely accepted that evidence-based medicine has contributed significantly to the practice of medicine and advancement of medical science. Every doctor should strive to contribute to the generation of evidence by conducting research.[1] For carrying out a research study, adequate knowledge, practical skills, and development of the right attitude are crucial.[2]

When we consider the medical research scenario in India, we find that quality research in India is limited. The number of research articles published in this field are few. As per the data available till 2008, India holds the twelfth rank among the productive countries in medicine research consisting of 65,745 articles with a global publication share of 1.59%.[3] There is also a need to improve the existing medical education system, to foster research culture. The medical education system in India does not incorporate research methodology as a part of the curriculum. It is seen that research programs in medical colleges get the lowest priority. There are a numbers of reasons, including lack of funding and manpower resources, responsible for the poor quality in research-oriented medical education.[4] A study has shown that there are around 100,000 undergraduate medical students in India, out of whom just 0.9% of the students had shown interest in research through various research programs.[5] From this, it is clear that the inclination for research is poor among undergraduate medical students who are future resident doctors (postgraduate students). As per the Medical Council of India (MCI) requirements, resident doctors have to carry out a dissertation project as a part of their MD/MS curriculum. It is a common observation that a majority of resident doctors conduct research projects during the second or third years of residency.[6] In order to encourage research orientation in resident doctors, currently MCI has made it mandatory to not only attend one international/national conference, but also give an oral/poster presentation and send the article for publication.[7]

A review of literature showed that the data regarding knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward medical research among resident doctors pursuing postgraduate studies in India, is lacking. It is felt that the existing level of knowledge and awareness among the second and third year resident doctors who have already conducted / are conducting at least one research study for their dissertation should be evaluated. So, we decided to undertake a cross-sectional study to assess research-related knowledge, attitude, and practices of resident doctors of a medical college affiliated to a tertiary care hospital in western India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics approval

The study was commenced after obtaining permission from the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional survey during the period between September and October 2010.

Study participants

Out of a total of 420 residents who were admitted to the MD/MS course, we enrolled 100 residents; pursuing their second and third years of residency, from all the specialties. Those residents who had started or completed at least one research project were approached by word-of-mouth communication and the questionnaire was administered to them after seeking verbal consent.

Data collection tool

We developed a pre-tested, structured questionnaire based on our study objectives, taking guidance from the previous literature.[8–10] It was subjected to a thorough peer review by five senior teachers from the college. The questionnaire was also administered to 10 resident doctors to validate its content. It was subsequently modified as per suggestions of the teachers and resident doctors and the final questionnaire consisted of 29 multiple choice questions.

The questionnaire consisted of several parts. The first part pertained to a collection of demographic information of the residents: Age, gender, academic year, and faculty. The questions in the second part of the questionnaire assessed the residents’ knowledge about research methodology and statistics, and their attitude toward research. The third part of the questionnaire addressed questions related to their practices in research, for example, studies conducted earlier other than the dissertation, oral or poster presentation in national and international conferences, participation in workshops, publications, and prior training in research methodology.

Statistics

The data was expressed in percentage and was analyzed using descriptive statistics.

RESULTS

Out of 100 residents recruited in the study, 50 were in the second year of residency, while the remaining 50 were in the third year. A total of 46 residents were from clinical specialties and 54 were from pre- and para-clinical specialties.

The data related to the knowledge domain is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Knowledge domain: Percentage of responses

The responses regarding the attitude of residents toward research are summarized in Table 2. Although 84% of the residents agreed that resident doctors should be involved in medical research, a majority (86%) agreed that a separate time should be allotted in the curriculum for research activities.

Table 2.

Responses given by resident doctors to statements related to attitude

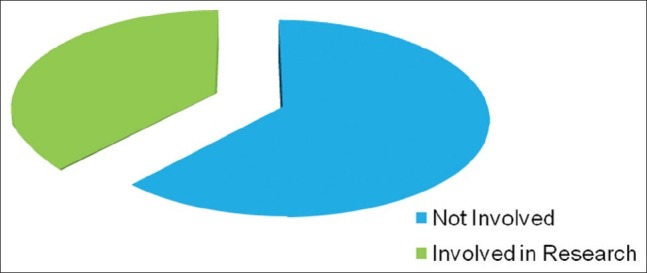

The data regarding research practices is presented in Tables 3 and 4 and in Figures 1 and 2.

Table 3.

Responses of resident doctors regarding research practices

Table 4.

Obstacles preventing residents from doing medical research

Figure 1.

Number of residents involved in the research, other than the dissertation

Figure 2.

Topics of research training that resident doctors would like to learn

Although 64% of the residents had attended research training workshops, very few of them pursued active research, as only 4% of them had published articles and 28% had presented research papers at a national conference. Only 28% of the residents stated that they read journals regularly.

The residents were asked to specify research-related topics for which they needed to be trained. The topics of research training of interest to the resident doctors are shown in Figure 2.

‘Lack of time’ was cited as an obstacle for research by 74% of the residents, of which 66% felt that training in their specialty consumed most of their time and 42% of the residents admitted ‘lack of research curriculum’ as an obstacle. The residents were asked to state factors that could promote research. Most of them (66%) admitted that guidance from senior faculty was essential. Forty-six percent thought that reduction of working hours of residency could lead to more research involvement and 40% felt that financial assistance would help to promote research. Forty-four percent considered that a system of extra credit points for research-related presentations and publications would be helpful.

DISCUSSION

Postgraduate students are introduced to the concept of designing and conducting research during residency. Medical research carried out by undergraduate and postgraduate students in India is disappointing compared to developed countries. To date research has not become a mandatory part of the curriculum of undergraduate medical education in India. In Germany, where research is an integral part of undergraduate medical curriculum; medical students were involved in 28% of the publications in a particular institution.[11] A study reported that in a European country, Croatia, 23% of the undergraduate students were involved in research projects.[12] We carried out this study to assess the awareness of residents toward research and to find out whether the current methods of training and facilities are adequate to foster a research culture in postgraduate students.

This study showed various key findings that would be of interest to medical educators and policy makers. It was found that knowledge about the need and prerequisites of research was fairly good among resident doctors. Furthermore, they also showed a positive attitude toward medical research. However, there was disparity found with regard to their attitude toward medical research and actual participation. Although a majority of the postgraduate medical residents wished to get involved in research, very few had participated in research work, other than the mandatory dissertation project. Moreover, very few had presented research papers at conferences or had publications. Discrepancy between attitude and practice was also highlighted in a study done in Faisalabad, in India. Although a large majority of postgraduate trainees of the Allied Hospital in Faisalabad appreciated the importance of reading current literature, only a few actually read journals and were actively involved in presenting research papers and making scientific contributions to the literature.[13] Similar results were obtained in a study done in Madison, in USA. Out of 143 postgraduate students, 85% felt that research experience was desirable, 48% were interested in pursuing research during residency, and only 8% were active in research.[14] However, two studies that were carried out in Canada and Pakistan reflected a contrasting attitude of residents that a majority of time in residency should be spent learning the clinical aspects of their specialty and they were unwilling to sacrifice personal time for research.[10,15] In our study, residents reported significant barriers impeding research during residency, such as, lack of time, inadequate guidance from teaching staff, and financial support. Similar obstacles for research among residents have been reported in a study done by Khan et al.[16] Residents were interested to learn statistics, Good Clinical Practices, medical ethics, and protocol writing. Hence, a research curriculum considering these topics should be formulated.

Formal evaluation should also be done during university examinations, to ensure that resident doctors learn these aspects. Medical teachers should be trained in research methodology and they should motivate their postgraduate students in undertaking research. It is suggested that not only the teaching abilities, but the research experience of a teacher could be assessed at the time of their appointment by the university. As lack of time due to clinical work was cited as the main obstacle by a majority of resident doctors. Before starting the research study, the protocol should be discussed by the faculty members and the research study should be planned. The faculty members should not only assess research work periodically, but also provide the necessary information and guidance to resident doctors. Lack of research curriculum was also cited as a hurdle in the present study by most of the resident doctors. For training in research methodology, medical colleges should conduct training programs. For encouragement of medical postgraduate students, a system of rewarding the best thesis study may be started. Conferences and workshops specially organized for resident doctors should be conducted. Journal editors can encourage research among postgraduate students by having a policy to give priority to the thesis articles that have won awards. When offering jobs in government and private medical sectors and admission to super-specialty courses, preference could be given to resident doctors who have carried out and published research studies.

We recognize several limitations of our study. First, our study was based on the convenience sampling method, including only 100 residents, thus the residents who completed the survey may not reflect the knowledge, practices, and attitudes of all postgraduate residents. Second, this study involved only one medical college, further limiting the generalization of our results. Third, we could not include the questions that reflected a broad range of topics in the research for evaluation of the knowledge aspect of resident doctors.

Our study revealed that the residents have a fair knowledge about research. They have a positive attitude toward research, but they fail to transform their knowledge and attitude into actual practices. This could be due to lack of time or lack of research curriculum. It is recommended that a separate module of one-to-three month's duration, related to ‘Medical Research,’ be incorporated in the postgraduate medical curriculum by the MCI. If steps are not taken at an early stage for medical postgraduates who will walk the path of research in future, the quality of research and its application may be compromised.[17]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sackett DL, Roseberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it is isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312:71–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhatt A. Mumbai: Pharma BioWorld; 2005. The Challenge of growth in clinical research: Training gap analysis; pp. 56–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta BM, Bala A. A scientometric analysis of Indian research output in medicine during 1999-2008. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2011;2:87–100. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.82313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Requirement for Research Oriented Medical Education in India in Entrance Exams 2012 Education and Career in India. 2011. [Last accessed on 2011 Nov 15]. Available from: http://entrance-exam.net/requirement-for-research-orientedmedical-education-in-india/

- 5.Deo MG. Undergraduate medical students’ research in India. J Postgrad Med. 2008;54:176–9. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.41796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Post Graduate Medical Education Regulations 2000. [Last accessed on 2011 Nov 14]. Available from: http://www.mciindia.org/RulesandRegulations/PGMedicalEducation Regulations2000.aspx .

- 7.Medical Council of India Postgraduate Medical Education regulations, 2000. [Last accessed on 2011 Nov 14]. Available from: http://www.mciindia.org/rulesand-regulation/Postgraduate-Medical-Education-Regulations-2000.pdf .

- 8.Vodopivec I, Vujaklija A, Hrabak M, Lukić IK, Marusić A, Marusić M. Knowledge about and attitudes towards science of first year medical students. Croat Med J. 2002;43:58–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sumi E, Murayama T, Yokode M. A survey of attitudes toward clinical research among physicians at Kyoto University Hospital. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silcox LC, Ashbury TL, Vandenkerkhof EG, Milne B. Residents’ and Program Directors’ Attitudes Toward Research During Anesthesiology Training: A Canadian Perspective. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:859–64. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000194874.28870.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cursiefen C, Altunbas A. Contribution of medical student research to the Medline-indexed publications of a German medical faculty. Med Educ. 1998;32:439–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1998.00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolcić I, Polasek O, Mihalj H, Gombac E, Kraljević V, Kraljević I, et al. Research involvement, specialty choice, and emigration preferences of first year medical students in croatia. Croat Med J. 2005;46:88–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aslam F, Qayyum MA, Mahmud H, Qasim R, Haque IU. Attitudes and practices of postgraduate medical trainees towards research- A snapshot from Faisalabad. J Pak Med Assoc. 2004;54:534–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Temte JL, Hunter PH, Beasley JW. Factors associated with research interest and activity during family practice residency. Fam Med. 1994;26:93–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCrindle BW, Grimes RB. Will pediatric residents do research? A survey of residents’ attitudes. Ann R Coll Physicians Surg Can. 1993;26:283–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan H, Khan S, Iqbal A. Knowledge, attitudes and practices around health research: The perspective of physicians-in-training in Pakistan. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9:46. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-9-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajadhyaksha V. Training for clinical research professionals: Focusing on effectiveness and utility. Perspect Clin Res. 2010;1:117–9. doi: 10.4103/2229-3485.71767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]