Abstract

Background:

Chronic gingivitis is the most prevalent in all dentate animals. Regular methods for controlling it have been found to be ineffective, which have paved the way for the use of herbal products as an adjunctive to mechanical therapy as they are free to untoward effects and hence can be used for a long period of time.

Objective:

The antigingivitis effect of a gel containing pomegranate extract was evaluated using a 21-day trial in patients with chronic gingivitis.

Materials and Methods:

Forty patients participated in this randomized clinical study, carried out in four phases of 7 days each over 21 days. The patients were randomly assigned to four groups: First group was treated with mechanical debridement and an experimental gel and the second group with mechanical debridement and a control gel; the third group wasn’t subjected to mechanical debridement and only experimental gel was used. The fourth group was treated with control gel only. All the groups were subjected to various clinical and microbiological parameters to evaluate the antiplaque and antigingivitis effect of the pomegranate extract.

Results:

The group which used the pomegranate gel along with mechanical debridement showed significant improvement in all the clinical and microbiological parameters included in the study when compared with the other three groups.

Conclusion:

Hence it can be concluded that the pomegranate gel when used as an adjunct with mechanical debridement was efficient in treating gingivitis.

Keywords: Chronic gingivitis, dental plaque, pomegranate

INTRODUCTION

Periodontal diseases are ubiquitous, affecting all dentate animals. Among various periodontal disease affecting humans, the most prevalent is gingivitis, affecting more than 90% of the population, regardless of age, sex, or race.[1]

Dental plaque is a sticky film of invisible layer of bacteria that hangs around the gums, tongue, teeth, and other dental restorations. Plaque if not removed regularly, leads to tooth and periodontal disease which eventually leads to tooth loss.

Gingivitis is a chronic inflammatory process limited to gingiva. It is defined as inflammation of the gingiva in which the junctional epithelium remains attached to the tooth at its origin level. The prevention of gingivitis by daily and effective supragingival plaque control is necessary to arrest its progression into periodontitis.[2]

Although mechanical plaque control methods have the potential to maintain adequate levels of oral hygiene, clinical experience and population-based studies have shown that such methods are not being employed as accurately as they should be by a large number of people. Therefore, several chemotherapeutic agents have been developed to control bacterial plaque, aiming at improving the efficacy of daily hygiene control measures.

The interest in plants with antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activities has increased to overcome the consequence of current problems associated with the wide-scale misuse of chemotherapeutic agents that induce microbial drug resistance.[1]

Various natural products like Astronium urundeuva, calendula, aloe vera, Curcuma zedoaria, and other herbs that had been used effectively since ages in Ayurveda are revisited and are been tested for their effectiveness in treating oral diseases with appreciable results.

Punica granatum (family Punicaceae), generally known as “pomegranate,” is a shrub or small tree native to Asia where several of its parts have been used as an astringent, and for hemostatic as well as diabetic control. The fruit of this tree is used for the treatment of throat infections, coughs, and fever due to its anti-inflammatory properties.[1]

In a study evaluating the effects of pomegranate on gingivitis, Pereira and Sampaio[3] showed a significant reduction in gingival bleeding after using a dentifrice containing the pomegranate extract. Yet in another similar study with a control group by Salgado et al.,[1] the effect of a gel with a pomegranate extract was tested on a group with experimental gingivitis which hardly mimics the naturally occurring gingivitis.

Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to compare and evaluate the efficacy of a gel containing the pomegranate extract in plaque formation in comparison to a control formulation and to evaluate the effect of the pomegranate gel on clinical parameters of naturally developed gingivitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of the pomegranate extract gel

Fresh pomegranates were obtained and their seeds were separated and ground into fine juice in an electric grinder. The concentrated extract was obtained through direct percolation by filtering the juice in a Buckner funnel through a filter paper. At this stage, a control gel was prepared by dissolving 5 g of carboxymethyl cellulose in 100 ml of distilled water and stirring it gently for 15 min until a gel of consistency (0.05%) convenient for usage, as the orabase gel, is obtained. Similarly, the test gel was prepared by dissolving 5 g of carboxymethyl cellulose in 100 ml of the concentrated extract of pomegranate juice. A very small amount of methyl paraben (2 mg) was added as a preservative to both test and control gels. The control gel had the same formulation except for the pomegranate extract.

Analysis

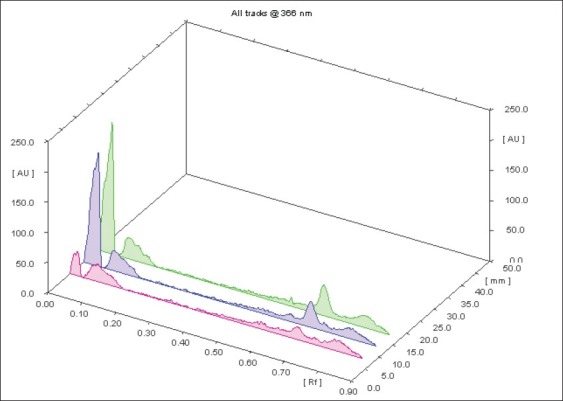

A densitometric high-performance thin layer chromatography analysis was performed for the development of the characteristic finger printing profile. The extract of the fruit was mixed with high-performance liquid chromatography grade methanol. The solution was centrifuged for 5 min and used for high-performance thin layer chromatography analysis. Then, 2 μl of the samples were loaded in the form of bands of width 7 mm in the 10 × 10 silica gel 60F254 thin layer chromatography plate using the Hamilton syringe and Camag Linomat 5 instrument. The sample-loaded plate was kept in the thin layer chromatography twin trough developing chamber (after saturation with solvent vapor) with the respective mobile phase (toluene–acetone–formic acid 4.5:4.5:1) up to 90 mm. The developed plate was dried using hot air to evaporate solvents from the plate. Then the peak display was identified, and is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

HPTLC analysis: Baseline display showing Peak (Rf values)

Test and control gels

Control and experimental gels were formulated and packed into small plastic containers for delivery to patients and it was made sure that volunteers were unaware about the content of the gel. All volunteers were delivered fresh samples of gels sufficient for the 7-day usage on their periodic recall visits. The volunteers were instructed to massage the provided gel onto their gums twice daily, morning and night, for 3–5 minutes. No other oral hygiene instructions were given to the volunteers and they were asked to follow their routine oral hygiene method. Gels were delivered during first two visits only to check the sustainability of the product on consecutive visits.

Subjects

A total of 40 patients (17 males and 23 females aged 20–45 years with chronic generalized gingivitis from the outpatient department of periodontics, Sri Hasanamba Dental College and Hospital, Hassan, Karnataka, India) were enrolled for this study based on inclusion and exclusion criteria.

All subjects had at least 24 natural teeth, were apparently healthy, and had clinical signs of gingivitis. All patients were informed about the nature of the study and signed the informed consent form in compliance with the study guidelines. Patients with a probing depth of ≥4 mm in any tooth, history of antibiotic coverage in last 6 months preceding the study or on long-term exposure to anti-inflammatory drugs, and history of periodontal therapy including oral prophylaxis in the last 6 months, and also smokers, pregnant women, and those who were allergic to the pomegranate fruit were excluded from the study.

Clinical study design

This study was a randomized, and intragroup comparisons of four groups of patients in four experimental phases of 7 day each for 21 days were done. The patients were randomly divided into 4 groups of 10 in each:

Group A: Patients received scaling and root planning (SRP) and were delivered a gel containing the pomegranate extract.

Group B: Patients received SRP and were delivered the placebo gel.

Group C: Patients did not receive any basic therapy but were delivered a pomegranate gel

Group D: Patients did not receive any therapy and were delivered a placebo gel for application.

During each visit of the 21-day experimental period, that is on baseline, day 7, day 14, and day 21, the plaque index (PI), gingival index (GI), and papillary bleeding index (PBI) were recorded and plaque samples were collected using sterile probes on one particular surface for each patient; fresh samples of the gel sufficient for usage for next 7 days were delivered.

Microbiological analysis

Collected plaque samples were transferred and spread onto two clean, sterile microscopic slides, and were stained with Gram's stain. Stained slides were used to make a reliable semiquantitative assessment of morphologically different types of bacteria. Each slide was examined with a bright-field microscope at ×100 magnification. Visible bacteria were counted in five randomly selected microscopic fields.

The microbiological status was coded in grades as below:

<5 organisms – +

5–10 organisms – ++

10–20 organisms – +++

>20 organisms – ++++.

Statistical analysis

For the recorded PI (Silness and Loe)[15], GI (Loe and Silness)[16] and PBI (Mulhemann)[17], intragroup comparisons were done using paired t-test or Wilcoxon's signed rank test between baseline and day 21, and intergroup comparisons were done by one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan's range test. For groupwise comparisons, Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA was done followed by the Mann–Whitney test. For all the tests, a P value of 0.05 or less was considered for statistical significance. For microbiological analysis results, Wilcoxon's signed rank test was used for intragroup comparisons followed by the Mann–Whitney test and Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA for intergroup comparisons. The comparison of the microbial status between different groups was analyzed using the Chi-square test.

Results were expressed as means±SDs and median values whenever required. Clinical parameters were analyzed by parametric tests and microbiological parameters by nonparametric methods. A P value of 0.05 or less was considered for statistical significance.

RESULTS

All 40 patients completed the clinical trial. The experimental gel had good acceptance and did not show adverse effects, such as ulceration or allergic reactions.

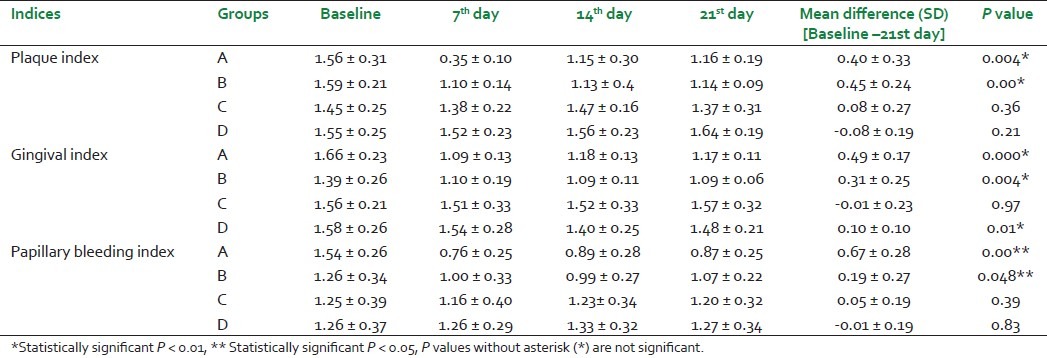

On the baseline, all group individuals had significantly higher plaque scores. Control and experimental groups A and B showed statistically significant differences with respect to PI, GI, and PBI [Table 1] from the baseline to day 21 whereas the groups which were treated with gels without SRP (groups C and D) did not show this difference.

Table 1.

Plaque Index, Gingival Index, and Papillary Bleeding Index

But the difference between these respective groups at the end of the experimental period was statistically significant only with respect to the PBI. The rest of the groups did not show a statistically significant difference.

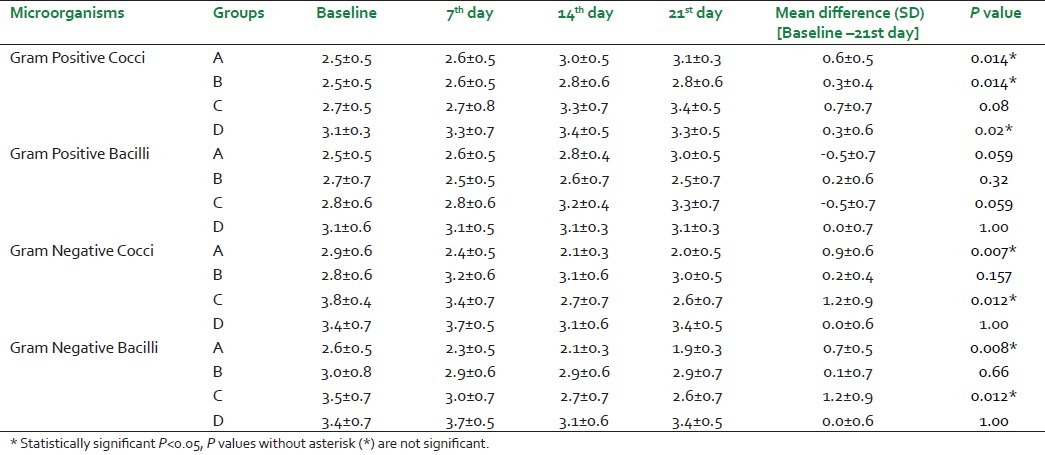

With respect to the microbiological results [Table 2], there was a statistically significant difference in the values of Gram-negative cocci and bacilli in the groups which used the pomegranate extract both with and without SRP whereas with respect to Gram-positive cocci and bacilli, this difference was not seen between the groups.

Table 2.

Gram Positive Cocci, Gram Positive Bacilli, Gram Negative Cocci and Gram Negative Bacilli

DISCUSSION

Plaque is the main agent responsible for the breakdown of periodontal tissues leading to periodontal disease. The removal of this plaque regularly is of paramount importance in the prevention of periodontal disease.

The inability of the adult population to perform adequate mechanical tooth cleaning has stimulated the search for chemotherapeutic agents added to dentifrices to improve plaque control and prevent gingivitis.[4] So various means have been established and search is going on to reduce the bacterial load. Herbal products are one group of agents which has been used extensively in reducing the bacterial population. Phytotherapeutic products have been investigated with these purposes and have shown satisfactory results.[5–7] This made us to evaluate the efficacy of P. granatum as an antiplaque agent.

The antibacterial activity of P. granatum has been evaluated in previous studies with good results. Trivedi and Kazmi,[8] using extracts of fruit barks, have observed an antibacterial activity against Bacillus anthracis and Vibrio cholerae while Machado et al.[9] showed a similar effect against Staphylococcus aureus, in agreement with Prashant and Asha.[10] All the above-mentioned studies had used either the bark or the leaves of the P. granatum tree or were tried and tested on only one particular group of organism. This made us to take up this study which finds the efficacy of the fruit extract in preventing plaque and also its effect on morphotypes of organisms which gives an overall view of its effect on plaque organisms as established in Goodson's work where he has distinguished the presence of morphotypes of organisms under different conditions. On the basis of this work, analysis of the P. granatum fruit extract in morphotypes of plaque bacteria was also made.

Considering that flavoring agents can promote a moderate antiplaque affect[4] and contents of test and control gels were different only with respect to the presence of the pomegranate extract, results show that this agent did not have an additional effect in reducing plaque formation and signs of gingivitis unless it was supplemented with basic therapy. These data are not in agreement with those of a previous in vitro study by Periera et al.[11] which showed that a bacterial strain present in supragingival plaque, namely, Streptococcus sanguis, was sensitive to different concentrations of the pomegranate extract, which demonstrated an inhibitory action similar to that of chlorhexidine. It should be highlighted, however, that in vitro studies do not reproduce exactly the oral conditions.

In the present study, the pomegranate extract gel did not avoid plaque formation during the trial, as suggested by Kakiuchi et al.[12] and Pereira et al.[11] but there was a significant reduction in the plaque score compared to the group which used the placebo gel. Possible explanation for this effect is the antibacterial agents present in pomegranate – hydrolysable tannins – that form complexes of a high molecular weight with soluble proteins, increase bacterial lysis, and moreover interfere with bacterial adherence mechanisms on tooth surfaces.[9,12,13]

This study showed a significant difference in PBIs between experimental and control groups. These results are consistent with those reported by Pereira and Sampanio,[3] who showed a significant reduction in gingivitis using the dentifrice containing the pomegranate extract. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that a control group was not included in that study, which had not allowed the assessment of the actual gingivitis reduction rate related exclusively to mechanical plaque control.

According to Ross et al.[14] the anti-inflammatory effect of pomegranate may be attributed to its considerable immunoregulatory activity over macrophages and T- and B-lymphocyte subsets. The score used in this study only evaluates the presence or absence of bleeding; it does not allow the assessment of other characteristics of the inflammatory process, such as edema, changes in gingival contour, and loss of tissue attachment. Therefore, the possible effect of the P. granatum extract on controlling the severity of gingivitis is not very clear.

Microbiological data showing unaltered values of Gram-positive cocci and bacilli suggest that the pomegranate extract might have had no effect on the natural habitats of the oral cavity as it's a natural product unlike chemotherapeutic agents which alongside being bactericidal to pathogenic flora also disrupt the normal flora of the oral cavity. But the reduction in the counts of Gram-negative bacilli and cocci in the groups which used the pomegranate extract in comparison to the group using the control gel suggests that it might have had some bactericidal activity on these pathogenic species.

The use of carboxymethyl cellulose as the carrier for the pomegranate extract has proved to be efficient in improving the gingival condition as carboxymethyl which is a commonly used orabase gel has significant sustainability on the oral tissues.

Though the difference between the groups with the pomegranate extract with respect to the GI and PI is not statistically significant, clinical conditions showed considerable difference from the groups which used the control gel.

The group which was treated without SRP did not show any statistically significant difference between the groups which used pomegranate and control gel showing that the pomegranate extract on itself would not be so very effective in treating gingival disease without the basic therapy. So the basic therapy remains the gold standard for the treatment of the periodontal therapy.

Due to the lack of clinical trials with a similar design investigating the effect of pomegranate on gingivitis, the data of this study were evaluated by parallel inferences, taken off from nonspecialized articles. Therefore, more clinical trials with a similar design using different concentrations of pomegranate are necessary to verify its action upon plaque microflora in vivo and severity of gingivitis. Further research will be needed to identify the real benefits of pomegranate as a therapeutic and preventive agent for gingivitis, in addition to its common use in popular medicine.

CONCLUSION

Within the limits of this clinical study, it can be concluded that the gel containing pomegranate extract was efficient in treating gingivitis when used along with mechanical cleaning in controlling plaque and gingivitis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Salgado AD, Maia JL, Pereira SL, de Lemos TL, Mota OM. Antiplaque and antigingivitis effects of a gel containing Punica granatum Linn extract.A double-blind clinical study in humans. J Appl Oral Sci. 2006;14:162–6. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572006000300003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakdash B. Current patterns of oral hygiene product use and practices. Periodontal. 2000;1995(8):11–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1995.tb00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pereira JV, Sampaio FC. Estudos com o extrato da punica granatum linn (roma): Efeito antimicrobiano in vitro e avaliacao clinica de um dentrifricio sobre microorganismos do biofilme dental [abstract] Journal da Aboprev. 2003;Fev-abr:8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nogueira-Filho GR, Toledo S, Cury JA. Effect of 3 dentrifices containing triclosan and various additives.An experimental gingivitis study. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:494–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027007494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lorenzo MR, Madrigal GR, Pineda JP. Efectos de la tintura de calendula al 10 porciento en adolescents afectados por gingivitis cronica. ediCiego. 1997;3:33–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pannuti CM, Mattos JP, Ranoya PN, Jesus AM, Lotufo RF, Romito GA. Clinical effect of a herbal dentifrice on the control of plaque and gingivitis.A double-blind study. Pesqui Odontol Bras. 2003;17:314–8. doi: 10.1590/s1517-74912003000400004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villalobos OJ, Salazar CR, Sanchez GR. Efecto de un enjuague bucal compuesto de aloe vera en la placa becteriana e inflamacion gingival. Acta Odontol Venez. 2001;39:16–24. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trivedi VB, Kazmi SM. Kachnar and anar as antibacterial drugs. Indian Drugs. 1979;16:295–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Machado TB, Pinto MC, Leal IC, Silva MG, Amaral AC, Kuster RM, et al. In vitro activity of Brazilian medicinal plants, naturally occurring napthoquinones and their analogues against methicillin-resistant staplylocaccus aureus. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;21:279–84. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00349-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prashanth D, Asha MK, Amit A. Antibacterial activity of punica granatum. Fitoterapia. 2001;72:171–3. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00270-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pereira JV, Silva SC, Filho LS, Higino JS. Atividade antimicrobiana do extrato hidroalcoolico da punica granatum Linn sobre microorganisms formadores de placa bacterriana. Rev Periodontia. 2001;12:57–64. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kakiuchi N, Hattori M, Nishizawa M, Yamagishi T, Okuda T, Namba T. Studies on dental caries prevention by traditional medicines. VIII. Inhibitory effect of various tannins on glucan synthesis by glycosyltransferanse from streptococcus mutans. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1986;34:720–5. doi: 10.1248/cpb.34.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gracious Ross R, Selvasubramanian S, Jayasundar S. Immunomodulatory activity of punica granatum in rabbits – a preliminary study. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;78:85–7. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00287-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Machado TB, Leal IC, Amaral AC, Santo KR, Silva MG, Kuster RM. Antimicrobial ellagitannin of punica granatu fruits. J Braz Chem Soc. 2002;13:606–10. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macgregor ID. Silness and Loe Index-Clin Prev Dent. 1987;6:9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischman SL. Current status of indices of plaque. (379-80).J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:371–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1986.tb01475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kruger KF. Muhlemann Bleeding Index - Stomatol DDR. 1983;5:342–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]