Abstract

Objective

We sought to assess the long-term faith of migraine in patients with high risk anatomic and functional characteristics predisposing to paradoxical embolism submitted to patent foramen ovale (PFO) transcatheter closure.

Methods

In a prospective single-center non randomized registry from January 2004 to January 2010 we enrolled 80 patients (58 female, mean age 42±2.7 years, 63 patients with aura) submitted to transcatheter PFO closure in our center. All patients fulfilled the following criteria: basal shunt and shower/curtain shunt pattern on transcranial Doppler and echocardiography, presence of interatrial septal aneurysm (ISA) and Eustachian valve, 3-4 class MIDAS score, coagulation abnormalities, medication-refractory migraine with or without aura. Migraine Disability Assessment Score (MIDAS) was used to assess the incidence and severity of migraine before and after mechanical closure. High risk features for paradoxical embolism included all of the following.

Results

Percutaneous closure was successful in all cases (occlusion rate 91.2%), using a specifically anatomically-driven tailored strategy, with no peri-procedural or in-hospital complications; 70/80 of patients (87.5%) reported improved migraine symptomatology (mean MIDAS score decreased 33.4±6.7 to 10.6±9.8, p<0.03) whereas 12.5% reported no amelioration: none of the patients reported worsening of the previous migraine symptoms. Auras were definitively cured in 61/63 patients with migraine with aura (96.8%).

Conclusions

Transcatheter PFO closure in a selected population of patients with severe migraine at high risk of paradoxical embolism resulted in a significant reduction in migraine over a long-term follow-up.

Keywords: Migraine, stroke, patent foramen ovale, transcatheter closure

Introduction

Migraine is a recurrent and potentially disabling headache affecting up to 10% of the population, being the association with aura around 25% [1]. While prior non-randomized studies involving non-homogeneous patient cohorts have suggested a beneficial role for PFO closure in migraine therapy, much controversy still lingers regarding this clinical question [2-3]. Moreover, although the study has a number of flaws, the only randomized trial, the Migraine Intervention with Starflex Technology (MIST) trial [4], failed to show significant benefit from PFO percutaneous closure. In our previous experience it has been suggested that in patients with high risk profile for paradoxical embolism severe migraine can be significantly reduced by means of transcatheter closure, at least in the short follow-up. We sought to assess the long-term faith of migraine symptoms of patients with high risk anatomic and functional characteristics predisposing to paradoxical embolism submitted to PFO transcatheter closure.

Materials and methods

In a prospective single-center non randomized registry from January 2004 to January 2010 we enrolled 80 patients 80 patients (58 female, mean age 42±2.7 years) with severe, disabling, medication-refractory migraine and documented PFO underwent transcatheter PFO closure in our center (Table 1). Migraine was diagnosed according to the International Headache Society criteria [5]: Migraine Disability Assessment Score (MIDAS) [6] was used to assess the incidence and severity of migraine headache by an independent neurologist. Clinical and procedural data were collected and analysed by a mixed team of one cardiologist and one neurologist.

Table 1.

Patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics

| Mean or % | |

|---|---|

| Age(years) | 38.9±5.8 |

| Female | 58/80(72.5) |

| Migraine with aura : | 63/80(78.5) |

| - blurred vision, hemianopsia, cortical blindness | 47/80(58.7) |

| - hemi-lateral loss of strength and paresthesias | 16/80(20.0) |

| Migraine with no aura | 17/80(21.2) |

| MIDAS class 1-2 ( ) | 0/80(0) |

| MIDAS class 3-4 ( ) | 80/80(100) |

| R-L shunt grade 1 | 0/80 (0) |

| Mean number of migraine without aura attacks/month | 1.1±0.2 |

| Mean number of migraine with aura attacks/month | 4.2±0.8 |

| R-L shunt grade 2 | 24/80 (30) |

| R-L shunt grade 3 | 39/80 (48.7) |

| TC Doppler trivial shunt (<15 bubbles) | 0/80 (0) |

| TC Doppler shower pattern | 22/80 (27.5) |

| TC Doppler curtain pattern | 41/80 (52.2) |

| Interatrial septal aneurysm (on TEE) | 80/80(100) |

| White-matter lesion on cerebral MRI | 45/80(56.5) |

| Deficiency of anti-thrombin III, protein C, S | 28/80 (35) |

| Factor V Leiden | 7/80 (8.7) |

| Antiphospholipid or anticardiolipin | 7/80 (8.7) |

| Hyper-homocysteinemia | 38/80 (47.5) |

TEE: transesophageal echocardiography; TC: transcranial Doppler

Inclusion criteria

Criteria for intervention were driven by previous authors’ experience as well as prevailing literature and included all the following: curtain shunt pattern of R-L shunt on transcranial Doppler[7] and transesophageal echocardiography, refractory and disabling migraine (with 3-4 class MIDAS score) with or without Aura, PFO, right-to-left (R-L) shunt during normal respiration [8], interatrial septal aneurysm (ISA) [9], coagulation abnormalities (including Leiden Factor V mutation, MHTFR mutation, C and S protein, anticardiolipin and antiphospholipid autoantibodies, antithrombin III) [10], and presence of Eustachian valve (EV) [11]. Refractory disabling migraine was defined as migraine with MIDAS > 25, refractory to conventional drug therapy, including personalized dosage of beta blockers, antidepressive drugs, tryptan, and antinflammatory medications. All patients were informed of and consented to the off-label nature of the intervention. The study was approved by the local internal review board and ethics committee.

Echocardiographic protocols

Transcranial Doppler Ultrasound was performed following the current guidelines [12]. Transthoracic and/or transesophageal echocardiography was conducted using a GE Vivid 7 (General Electric Corp., Nowrfolk, VI, USA) with bubble test and Valsalva manoeuvre under local anaesthesia:shunt grading (grade 0= none, grade 1= 1-5 bubbles, grade 2= 6-20 bubbles, grade 3=≥20 bubbles); presence of EV; and ISA extension, classified according to Olivares et al [13], were obtained. Patients meeting criteria for the study were offered an intracardiac echocardiographic guided PFO closure using the mechanical 9F 9MHz UltraICE catheter (EP Technologies, Boston Scientific Corporation, San Jose, CA, USA). The intracardiac echocardiography study was conducted as previously described [14], by performing a manual pull-back from the superior vena cava to the inferior vena cava through 5 sectional planes; measurements of diameters of the oval fossa, the entire atrial septal length and rims were obtained with electronic calliper edge-to-edge in the aortic valve plane and the 4-chamber plane. PFO tunnel length was also measured, and EV presence was confirmed intra-procedurally. Intracardiac echocardiographic monitoring of the implantation procedure was conducted in the 4-chamber plane.

Device selection process

On the basis of intracardiac echocardiography findings and measurements [15], the operators selected either the Amplatzer Occluder family (PFO Occluder, Cribriform Occluder, or ASD Occluder, AGA Medical Corporation, Golden Valley, MN), the Premere Closure System (St. Jude Medical Incorporated, Saint Paul, MN) or the Biostar (NMT Corp, USA). The Amplatzer PFO Occluder was selected when the ISA was bidirectional with moderate motion (3RL or 3LR ISA). The Premere occlusion system was chosen in cases of absent, motionless, or unidirectional ISA (1R, 2L ISA); when PFO tunnel length was more or equal to 10 millimetres; and in all cases of thick septum secundum (thickness more than 10 millimetres). The Amplatzer Cribriform Occluder was selected in cases of multi-perforated ISA. The Biostar was selected in patients with proven severe nickel allergy. Care was taken to cross the most central hole in the oval fossa with the guide-wire during intracardiac echocardiography guidance. These devices were also selected for huge and bidirectional ISA (4-5RL ISA) to ensure as complete as possible coverage of the oval fossa on both sides of the interatrial septum. Device size selection involved ensuring that the entire left disk diameter did not exceed the entire interatrial septal length on intracardiac echocardiography measurement.

Follow-up protocol

Follow-up was conducted by means of transesophageal echocardiography at 1 month and, if even a small shunt was detected, at 6 months as well. Additionally, transthoracic echocardiography at 1, 6, and 12 month; transcranial Doppler at 1 month; Holter monitoring at 1 month; and clinic visit at 1, 6, 12 months were also performed. Residual shunt was assessed by contrast transesophageal echocardiography and Transcranial Doppler [16]. MIDAS evaluation was performed at 6, 12 months and yearly after the first year post- implantation; patients were interviewed regarding reduction or abolition of migraine and aura using a 4-grade scale:100% (total resolution), 50% reduction, 25% reduction, or 0% (unchanged). A minimum of 18 months of follow-up was required for inclusion in the final results.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square, ANOVA, and paired T-student tests were used to compare frequencies and continuous variables between groups. Statistical analysis was performed using a statistical software package (SAS for Windows, version 8.2; SAS Institute; Cary, NC). A probability value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

The procedure was successful in all patients (100%, Table 2-3) with no peri-procedural and in-hospital complications. After a mean follow-up of 50.1±16.8 months (range 24-76), PFO closure was complete in 91.2% on transthoracic echocardiography and Transcranial Doppler ultrasound. Seven patients (8.7%) had a persistent small shunt on transesophageal echocardiography (all patients had an Amplatzer ASD Cribriform Occluder 25 mm). Three other patients (3.7%) developed atrial fibrillation during the post-procedural period and were treated with antiarrhythmic drugs with restoration of sinus rhythm (two patients with an Amplatzer ASD Cribriform 30 mm and one patient with a Premere Occlusion system 20 mm). No aortic erosion or device thrombosis was observed during follow-up.

Table 2.

Intracardiac echocardiographic measurements of anatomic features of the interatrial septum (measurements are referred to the 4-chamber view)

| Anatomical characteristics | Mean (millimetres) |

|---|---|

| Diameter of the interatrial septum | 36 ±10.6 |

| Length of anterosuperior rim (aortic rim) | 5.4 ±1.2 |

| Oval fossa diameter | 24 ±6.9 |

| Patent oval foramen tunnel length | 13 ±3.9 |

| Patent oval foramen size | 5.9 ±0.4 |

| Rim thickness | 9.8 ±8.6 |

| Association of anatomical characteristics | Number of pts (%) |

| Long channel alone | 15/80(18.7%) |

| Large ISA (> 4 RL) alone | 25/80(31.2%) |

| Moderate ISA (>2 RL but <4 RL) alone | 17/80(21.2%) |

| Hypertrophic rims alone | 6/80(7.5%) |

| Long channel + moderate ISA | 10/80(12.5%) |

| Long channel + hypertrophic rims | 7/80(8.7%) |

Table 3.

Device type and size selection (number of patients).

| Device | 18 mm | 20 mm | 25 mm | 35 mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amplatzer PFO | - | - | 7 | 1 |

| Amplatzer MF | - | - | 42 | - |

| Premere | - | 10 | 17 | - |

| Biostar | 3 | - | - | - |

MF: multifenestrated

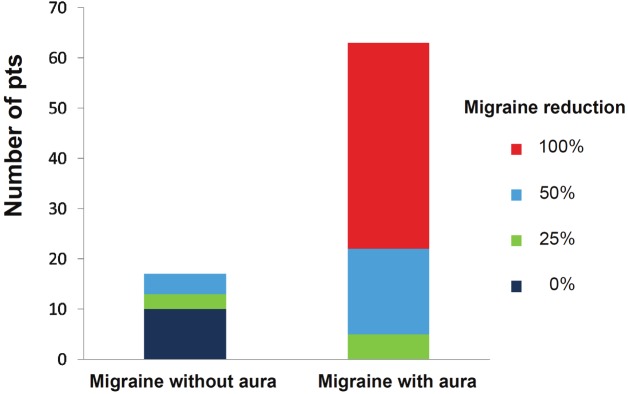

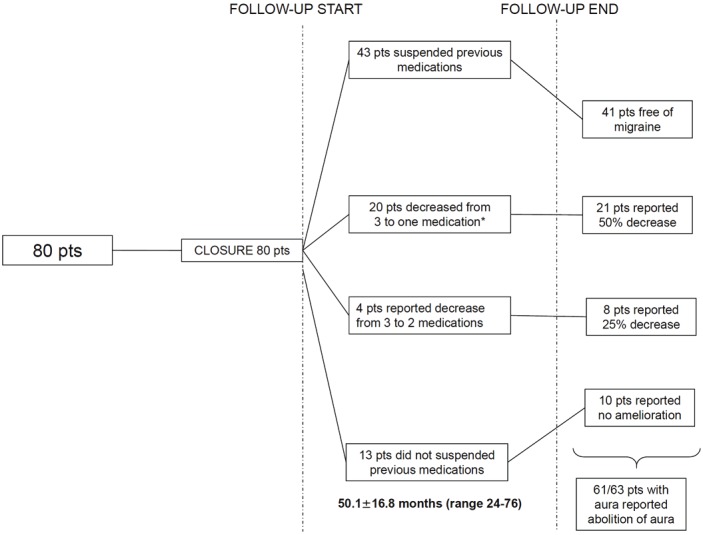

As regards as migraine symptoms faith, 70/80 of patients (87.5%) reported improved migraine symptomatology (mean MIDAS score decreased 33.4±6.7 to 10.6±9.8, p<0.03) whereas 12.5% reported no amelioration of migraine attacks (Figure 1): none of the patients reported worsening of the previous migraine symptoms. In specific, auras were definitively cured in the long-term follow up in 61/63 patients with migraine with aura (96.8%) after closure (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Changes in medical therapy during follow-up.

Figure 2.

Histogram representation of migraine withand without aura improvement following the abovedescribed 4-grade scale in patients presenting fortranscatheter closure.

Discussion

Our results confirmed over the long-term follow-up the positive effects of transcatheter closure in patients with anatomic and functional characteristics highly predictive of paradoxical embolism. In particular such cohort of patients responded very favourably to transcatheter PFO closure with aura symptoms amelioration maintained on the long-term.

To achieve even a modest acceptance, percutaneous closure of PFO to treat migraine, a potentially debilitating but nonetheless non-life threatening condition, must demonstrate a substantial benefit-to-risk ratio.

In our opinion, the past MIST trial inclusion criteria were not robust enough to support mechanical closure as an alternative and competitive therapy for severe migraine [4]. In particular, the exclusion of patients with coagulation abnormalities or with a serious risk of paradoxical embolization, the lacking report of the degree of shunt on Transcranial Doppler and a single-device type strategy irrespective of the specific patients’ interatrial septum characteristics, all probably affected the probability to impact on migraine.

In our previous series, we demonstrated that in patients without prior stroke, several anatomic and clinical criteria may be predictive of responders to percutaneous PFO closure for migraine therapy [17-19] and that when facing with PFO patients with recurrent stroke a specific anatomy-driven device tailoring strategy is likely to increase the closure rate and diminishing the complication rate [20-21]. In the current study, we evaluate the long-term follow-up of a population without previous cerebral paradoxical embolism who fulfilled those criteria: R-L shunt during normal respiration, curtain shunt pattern of R-L shunt on transcranial Doppler and transesophageal echocardiography, ISA, coagulations abnormalities, and presence of EV. According to the microembolic hypothesis recently demonstrated in the animals [22] and suggested also in humans [23-24] and the chemical embolism theory, these same characteristics have been previously linked to migraine, especially migraine with aura [24]. The meticulous strategy presented in our report, aimed to minimize even a mild ratio of complications, by means of a carefully specific anatomy-driven device tailoring process and risk stratification, appears to have an acceptable benefit-risk ratio and the global results seem to support further large scale trial on primary PFO closure for patients satisfying high-risk clinical and anatomic features for paradoxical embolism.

Limitations

We recognized several limitations to our study. Firstly, our patients sample size was small; however, we had set fairly stringent inclusion criteria, thereby limiting enrolment. Also, this was a single-center study and the non-randomized nature was clearly a limitation and as with any invasive intervention evaluation absent a sham arm, the potential for placebo bias cannot be fully ignored. This issue is particularly pertinent when outcomes relate to subjectively reported symptomatic improvements.

Conclusion

Despite the several above mentioned limitations, the current study confirmed on the long-term the results of our previous experience of primary PFO transcatheter closure in patients at high risk of paradoxical embolism [19], suggesting that a very positive benefit-risk balance can be obtained as regards of migraine symptoms and in particular aura symptoms in patients with functional and anatomical features highly predictive of paradoxical embolism. The positive impact of transcatheter closure is maintained over the long-term, fairly beyond that placebo-effect advocated as the explanation of migraine improvement in the previous series.

References

- 1.Schwedt TJ, Demaerschalk Bm, Dodick DW. Patent foramen ovale and migraine: a systematic review. Chephalalgia. 2008;28:531–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vigna C, Marchese N, Inchingolo V, Giannatempo GM, Pacilli MA, Di Viesti P, Impagliatelli M, Natali R, Russo A, Fanelli R, Loperfido F. Improvement of migraine after patent foramen ovale percutaneous closure in patients with subclinical brain lesions. A case-control study. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2009;2:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wahl A, Praz F, Findling O, Nedeltchev K, Schwerzmann M, Tai T, Windecker S, Mattle HP, Meier B. Percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale for migraine headaches refractory to medical therapy. Cathet Cardiovasc Intervent. 2009;74:124–129. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dowson A, Mullen MJ, Peatfield R, Muir K, Khan AA, Wells C, Lipscombe SL, Rees T, De Giovanni JV, Morrison WL, Hildick-Smith D, Elrington G, Hillis WS, Malik IS, Rickards A. Migraine Intervention With STARFlex Technology (MIST) Trial. A Prospective, Multicenter, Double-Blind, Sham-Controlled Trial to Evaluate the Effectiveness of Patent Foramen Ovale Closure With STARFlex Septal Repair Implant to Resolve Refractory Migraine Headache. Circulation. 2008;117:1397–1404. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.727271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olesen J. The International classification of headache disorders, 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24:1–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Whyte J, Dowson A, Kolodner K, Liberman JN, Sawyer J. An international study to assess reliability of the migraine disability assessment (MIDAS) score. Neurology. 1999;53:988–994. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.5.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anzola GP, Morandi E, Casilli F, Onorato E. Different degrees of right-to-left shunting predict migraine and stroke: data from 420 patients. Neurology. 2006;66:765–767. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000201271.75157.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rigatelli G, dell’Avvocata F, Cardaioli P, et al. Permanent shunt as a key factor in predicting the risk of stroke recurrence. J Am Coll Cardiol. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ueno Y, Shimada Y, Tanaka R, Miyamoto N, Tanaka Y, Hattori N, Urabe T. Patent Foramen Ovale with Atrial Septal Aneurysm May Contribute to White Matter Lesions in Stroke Patients. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;30:15–22. doi: 10.1159/000313439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cerrato P, Imperiale D, Bazzan M, Lopiano L, Baima C, Grasso M, Morello M, Bergamasco B. Inherited Thrombophilic Conditions, Patent Foramen ovale and Juvenile Ischaemic Stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2001;11:140–141. doi: 10.1159/000047627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rigatelli G, Dell’avvocata F, Braggion G, Giordan M, Chinaglia M, Cardaioli P. Persistent venous valves correlate with increased shunt and multiple preceding cryptogenic embolic events in patients with patent foramen ovale: an intracardiac echocardiographic study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;72:973–976. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sloan MA, Alexandrov AV, Tegeler CH. Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Assessment: transcranial Doppler ultrasonography: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2004;62:1468–1481. doi: 10.1212/wnl.62.9.1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olivares-Reyes A, Chan S, Lazar EJ, Bandlamudi K, Narla V, Ong K. Atrial septal aneurysm: a new classification in two hundred five adults. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1997;10:644–656. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(97)70027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rigatelli G, Hijazi ZM. Intracardiac echocardiography in cardiovascular catheter-based interventions: different devices for different purposes. J Invasive Cardiol. 2006;18:225–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rigatelli G, Dell’Avvocata F, Ronco F, Giordan M, Cardaioli P. Patent oval foramen transcatheter closure: results of a strategy based on tailoring the device to the specific patient’s anatomy. Cardiol Young. 2010;20:144–149. doi: 10.1017/S1047951109990631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boutin C, Musewe NN, Smallhorn JF, Dyck JD, Kobayashi T, Benson LN. Echocardiographic follow-up of atrial septal defect after catheter closure by double-umbrella device. Circulation. 1993;88:621–627. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.2.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rigatelli G, Braggion G, Aggio S, Chinaglia M, Cardaioli P. Primary patent foramen ovale closure to relieve severe migraine. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:458–459. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-6-200603210-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rigatelli G, Cardaioli P, Giordan M, Dell’Avvocata F, Braggion G, Chianaglia M, Roncon L. Transcatheter interatrial shunt closure as a cure for migraine: can it be justified by paradoxical embolism-risk-driven criteria? Am J Med Sci. 2009;337:179–181. doi: 10.1097/maj.0b013e31818599a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rigatelli G, Dell’Avvocata F, Ronco F, Cardaioli P, Giordan M, Braggion G, Aggio S, Chinaglia M, Rigatelli G, Chen JP. Primary transcatheter patent foramen ovale closure is effective in improving migraine in patients with high-risk anatomic and functional characteristics for paradoxical embolism. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:282–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rigatelli G, Cardaioli P, Dell’Avvocata F, Giordan M, Braggion G, Aggio S, Chinaglia M, Roncon L. The association of different right atrium anatomical-functional characteristics correlates with the risk of paradoxical stroke: an intracardiac echocardiographic study. J Interv Cardiol. 2008;21:357–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2008.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rigatelli G, Dell’avvocata F, Giordan M, Braggion G, Aggio S, Chinaglia M, Roncon L, Cardaioli P, Chen JP. Embolic Implications of Combined Risk Factors in Patients with Patent Foramen Ovale (the CARPE Criteria): Consideration for Primary Prevention Closure? J Interv Cardiol. 2009;22:398–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2009.00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nozari A, Dilekoz E, Sukhotinsky I, Stein T, Eikermann-Haerter K, Liu C, Wang Y, Frosch MP, Waeber C, Ayata C, Moskowitz MA. Microemboli may link spreading depression, migraine aura, and patent foramen ovale. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:221–229. doi: 10.1002/ana.21871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng TO. Potential source of cerebral embolism in migraine with aura: a transcranial Doppler study. Neurology. 1999;52:1622–1625. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.8.1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rigatelli G, Cardaioli P, Dell’Avvocata F, Giordan M, Nanjundappa A, Mandapaka S, Chinaglia M. May migraine post-patent foramen ovale closure sustain the microembolic genesis of cortical spread depression? Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2011;12:217–219. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rigatelli G. Migraine and patent foramen ovale:connecting flight or one-way ticket? Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8:1331–1337. doi: 10.1586/14737175.8.9.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]