Abstract

Glycosyltransferases (GlycoTs) catalyze the transfer of monosaccharides from nucleotide-sugars to carbohydrate, lipid and protein based acceptors. We examined strategies to scale-down and increase the throughput of glycoT enzymatic assays since traditional methods require large reaction volumes and complex chromatography. Approaches tested utilized: i) Microarray pin-printing. This method was appropriate when glycoT activity was high; ii) Microwells and microcentrifuge tubes. This was suitable for studies with cell lysates when enzyme activity was moderate; iii) C18 pipette tips and solvent-extraction. This enriched reaction product when the extent of reaction was low. In all cases, reverse phase-thin layer chromatography (RP-TLC) coupled with phosphorimaging quantified reaction rate. Studies with mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) demonstrate an increase in overall β(1,3)galactosyltransferase and α(2,3)sialyltransferase activity, and a decrease in α(1,3)fucosyltransferases when these cells differentiation towards cardiomyocytes. Enzymatic and lectin binding data suggest a transition from LeX type structures in mESCs to sialylated Galβ1,3GalNAc type glycans upon differentiation, with more prominent changes in enzyme activity occurring at later stages when embryoid bodies differentiated to cardiomyocytes. Overall, simple, rapid, quantitative and scalable glycoT activity analysis methods are presented. These utilize a range of natural and synthetic acceptors for the analysis of complex biological specimen that have limited availability.

Keywords: embryonic stem cells, cardiomyocytes, glycan, radioactivity, lectins, glycosyltransferase

INTRODUCTION

Glycosylation is an important post-translational modification that is catalyzed by the ‘glycosyltransferases’ (GlycoTs), a family of ~200 Golgi resident enzymes that comprise ~1% of the human genome [1]. These enzymes mediate the transfer of monosaccharides from nucleotide-sugar donors to either other carbohydrate substrates or to protein and lipid scaffolds. Phosphonucleotides and protons are by-products of this reaction. The specificity of the glycoTs varies in terms of the acceptor on which they act on, and the glycosidic linkage they catalyze. The sequential action of glycoTs results in the formation of diverse linear and branched glycan structures. Glycoproteins and glycolipids thus formed regulate an array of cellular processes including cell adhesion during inflammation [2] and cancer metastasis [3], stem cell proliferation and development [4], and microbial pathogenesis [5]. In these diverse applications, there is interest in quantifying glycoT activity in cells since they are important drivers of cell-surface glycan structure changes [6; 7; 8; 9]. Key challenges here relate to the ability to design assays that can discern between closely related glycoT activities and quantify enzyme activity when the available cells are scarce. These issues are addressed in the current manuscript.

Currently, glycosyltransferase enzyme assays may be classified into two categories. First, assays that measure reactions based on quantitation of the phosphonucleotide-leaving group or its derivative. Second, methods that follow the conversion of a specific acceptor to a product. Examples of the former approach include methods that detect enzyme activity based on proton release or pH changes [10; 11], phosphonucleotide detection using fluorescent chemosensors [12; 13], and phosphonucleotide derivative measurement by coupling with NADH oxidation [14] or phosphatase activity [15]. While such assays can be generalized for a range of enzymes and this may have applications in high-throughput assays, these methods have limited utility when complex enzyme mixtures are investigated. In particular, these methods cannot quantify a unique glycoT activity in complex cell lysates both due to the presence of closely related enzymes and also other cellular components that can interfere with signal detection [12]. The second class of glycosyltransferase assays can be solid-phase or solution-based. The solid-phase assays quantify product formation on two dimensional substrates by following the signal due to either fluorescently conjugated lectins that bind products [16; 17], biotinylated or azido derivatized carbohydrates that are incorporated during reaction [18; 19], or radioactivity [20; 21; 22; 23; 24]. While these approaches have merit, studies in microtiter plates, glycan microarrays or scintillation proximity assay formats have been limited to the analysis of recombinant enzymes. This may be due to the limited capacity of two-dimensional substrates to bear immobilized acceptors, which makes them more suitable to detect highly active enzymes only. Glycan immobilization also often requires a specialized panel of carbohydrates having uniform chemical coupling handles. Furthermore, mass transport limitations and challenges with quantifying immobilized acceptor amount on solid supports, makes it difficult to enumerate precise rate constants. Liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry represent additional methods to quantify enzyme activity [25; 26], though these have additional restrictions and they are technically complex.

The current manuscript revisits traditional glycoT assays [2; 27], with the goal of scaling-down the assay size. This can simultaneously reduce the number of cells needed as enzyme source and it can minimize radioactive reagent usage. Instead of traditional assays that use a combination of size-exclusion, affinity, hydrophobic-C18 and Dowex-1-formate chromatography, we demonstrate that reverse phase-thin layer chromatography (RP-TLC) can be used for the rapid separation of radiolabeled products from unreacted sugar-nucleotides for a surprisingly wide range of synthetic and natural carbohydrate acceptors. This enables reduction of glycoT reaction volume to <1 μL, increases assay throughput, and it minimizes contamination by confining the radioactive material to a solid phase. Phosphorimaging of TLC plates then allows quantitation of the extent of reaction. This step exploits the high sensitivity and wide linear dynamic range of this technology which extends over four orders of magnitude. The proposed method is validated using both recombinant enzymes and cell lysates. By following changes in glycoT activity of mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) as they differentiate towards beating cardiac myocytes, the study demonstrates a simultaneous increase in cellular α(2,3)sialyltransferase activity and a decrease in α(1,3)fucosyltransferase activity as the differentiation progresses.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Materials

Synthetic biotinylated acceptors were either from Glycotech (Gaithersburg, MD) or previous studies [2]. 14C labeled uridine diphosphate galactose (UDP-Gal, specific activity: 258 mCi/mmol), and guanosine diphosphate fucose (GDP-Fuc, 240 mCi/mmol) were purchased from Perkin Elmer (Waltham, Massachusetts) and American Radiolabeled Chemicals (ARC, St. Louis, MO) respectively. 14C labeled cytidine 5′-monophosphate N-acetylneuraminic acid (CMP-NeuAc) was from Perkin Elmer (293 mCi/mmol) and ARC (55 mCi/mmol).

Cell culture and differentiation

Mouse embryonic stem cells E14Tg2a were obtained from the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center (MMRRC, Univ. California, Davis, CA) and the mouse cardiac cell line HL-1 was kindly provided by Dr. W. Claycomb, (Louisiana State University Health Science Center, New Orleans, LA) [28]. Human promyeloid HL-60 cells, and breast cancer cell lines ZR-75-1 and MCF7 were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). All cells were cultured according to provider’s instructions.

In some cases, E14Tg2a mESCs were differentiation toward cardiomyocytes as described previously [29]. Briefly, single dispersed mESCs were seeded in Petri dishes to form embryoid bodies (EBs). Serum-free growth media, replenished every second day, consisted of DMEM (Mediatech, Manassas, VA) with 10% KnockOut serum replacer (KSR) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 10 ng/ml recombinant bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 0.055 mM β-mercaptoethanol, penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Mouse ESCs were cultured as EBs for 6 days with BMP4-supplemented medium. EB culture was continued for an additional day but without BMP4 and then the clusters were transferred to tissue culture dishes coated with 0.1% gelatin-phosphate-buffered saline at ~4–6 EBs/cm2. Spontaneously beating foci emerged as early as two days after plating and continue to mature up to day 16–20.

Glycosyltransferase reactions

Reaction buffer for GalT activity assays consists of 100 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), 7 mM ATP, 20 mM Mn Acetate, 1 mM UDP-Gal, 7.752 μM UDP-[14C]Gal (0.0024 μCi) and 5 mM acceptor. FucT reaction buffer contained 50 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.5), 5 mM MnCl2, 7 mM ATP, 3 mM NaN3, 4.167 μM GDP-[14C]Fuc (0.0012 μCi) and 1.5 mM acceptor. SialylT assay buffer contained 100 mM sodium cacodylate (pH 6.0), 6.826 μM CMP-[14C]NeuAc (0.0024 μCi) and 0.6 mM acceptor. In some instances, 14–280 mU/mL recombinant sialyltransferase from EMD Biosciences (San Diego, CA) was used as enzyme source. In other cases, cells cultured as described above were pelleted and stored at −80°C. Just prior to the enzyme assays, pellets with ~107 cells were lysed in ~100 μL 100 mM Tris Maleate buffer containing 2% Triton-X 100. Protein concentration was measured using the Coomassie-Bradford assay kit (Thermo-Pierce, Rockford, IL) and stocks were prepared by diluting lysates down to 10 mg/mL in cell lysis buffer. Enzyme reactions were then performed in buffer listed above using 1 mg/mL cell lysate as enzyme source. In all cases, in order to minimize evaporation, reaction mixtures were supplemented with 10% glycerol and assays were performed in a humidified chamber with >90% relative humidity.

Enzymatic reactions were performed in one of four different formats:

A. Pin printing

Here, a SpotBot2 microarrayer from ArrayIt (Sunnyvale, CA) was custom modified to hold the 1.57 mm diameter FPAM pins from V&P Scientific (San Diego, CA). 0.5 μL of recombinant sialyltransferase at 280 mU/ml was manually pipetted onto clean microscope glass slides. A second spot containing 0.6–1.88 mM acceptor and 56.81 μM 14C-labeled CMP-NeuAc in the sialyltransferase reaction buffer was then spotted on top of the enzyme drop using the microarrayer. The FPAM pin dispensed ~100 nL of reactant/spot, as determined using independent measurements. Pins were washed between spots to minimize carryover.

B. Microwell fabrication

Here, 32 flat-bottom wells with dimensions of 2 mm diameter×360 μm depth were fabricated in a 8×4 pattern on 50×75 mm microscope slides using photolithography. To this end, microwell patterns sketched using AutoCAD (San Rafael, CA) were transferred onto a high resolution plate (Microchrome, San Jose, CA) to generate a mask. SU8 2035 photoresist (MicroChem, Newton MA) was coated onto pre-cleaned microscope slides in two cycles. Each cycle involved spin coating of photoresist at 2500 rpm for 7 s to obtain a 180 μm-thick coat, solvent evaporation at 65°C for 4 min, curing at 95°C for 20 min and then cooling overnight. Once prepared, the microwell mask was placed on this photoresist coated glass slide and this was exposed to 365 nm UV radiation for 90 s. The photoresist was then developed using PGMEA (propylene glycol methyl ether acetate) solvent for 3 min followed by washing with isopropanol to remove photoresist that was not cross-linked. Sonication was then used as necessary to remove any residual photoresist. Glycosyltransferase reactions in volume of 1.2 μL were performed in these wells by pipetting 0.6 μL of acceptor, followed by addition of 0.6 μL reaction mixture containing the radioactive donor and cell lysate/recombinant enzyme.

C. Microcentrifuge reactions

Experiments performed in microcentrifuge tubes were similar to those in microwells, only the total reaction volume was 2–8 μL.

D. Product concentration using C18 pipette tip

C18 pipette tips (ZipTipC18®, Millipore, Billerica, MA) were used to concentrate product. To achieve this, the pipette tips were pre-wetted with 100% acetonitrile followed by equilibration with water. The reaction mixture was then diluted in equal volume of water, and this was pipetted/passed through the C18 tip 3–5 times. Product radioactivity in ‘original’ reaction mixture was quantified using RP-TLC (described in next section), along with ‘not bound’ product that did not bind the C18 pipette tip. Following this, the C18 pipette tip was washed twice using 3 μL water in order to elute any component that did not bind the hydrophobic matrix. Bound product was then released using two rinses with 1–1.5 μL of 100% methanol. Radioactivity associated with both ‘water’ washes and ‘methanol’ elutions was also quantified using the RP-TLC method.

When cell lysates were used as the enzyme source, an additional solvent extraction step was included to remove Triton-X since this reduced the binding of acceptor/product to the C18 matrix. Here, 20-fold excess water-saturated toluene was added to the reaction mixture. Following brief vortexing for 2–3 s, the sample was centrifuged at 13,000×g for 3 min on a tabletop microcentrifuge. The upper toluene layer containing Triton-X was discarded and the procedure was repeating two more times. At the end, the aqueous fraction was subjected to the C18 pipette tip concentration procedure.

Thin layer chromatography and analysis

Following enzymatic reaction, samples were blotted onto Silica gel 60 RP-18 reverse phase-TLC plates (RP-TLC, EMD-Chemicals). This was performed by simply overlaying the plate over the reaction spot in the case of the pin-printing and microwell assays. 0.5–1.5 μL of reaction mixture was pipetted onto the origin of the TLC plates in the case of the microcentrifuge tube and C18 pipette tip experiments. Water containing 0.2% acetic acid was the mobile phase. After the mobile phase moved 2–5 cm on the TLC plates, the plates were dried, wrapped in thin plastic, and exposed overnight to a Super Resolution (SR, Medium) phosphor screen (Perkin Elmer). The screen was imaged using a Cyclone Storage Phosphor System (Perkin Elmer).

Image analysis was performed using NIH-Image J (Bethesda, MD). The absolute amount of radioactivity in a given region was determined, using a calibrated TLC plate containing between 4–4,400 dpm of 14C radioactivity as the standard. Phosphorimaging of product resulted in sensitive detection of C-14 signal down to 4 dpm or 1.8 pCi. In some cases, ‘% conversion’ was quantified as dpm in product/(dpm in product + dpm in unreacted donor). In other cases, product formation was quantified in units of product dpm/mg protein, based on the amount of protein in each reaction mixture.

Lectin binding assays

40,000 mESCs at either day 0 or day 20 were plated onto wells of a 96-well microtiter plate. 30 h thereafter, cells were washed and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Fixed cells were stained with 50 μg/ml biotinylated lectins (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) for 1 h and binding was detected using anti-biotin HRP-linked antibody (Cell Signaling Tech, Davers, MA) and o- phenylenediamine substrate (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO). Biotinylated lectins used include Maackia amurensis lectin (MAL-II or MAH) which binds α2,3sialylated glycans with preference for the NeuAcα2,3Galβ1,3GalNAc structure [30] and Aleuria aurantia lectin (AAL) which recognizes α1,2/3/4/6 fucose residues on glycans [31].

Statistics

Error bars represent standard error mean for ≥3 experiments. Statistical tests were performed using the Students’s t-test for dual comparisons, and one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey test for multiple comparisons. *p<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant, unless specified otherwise.

RESULTS

Quantifying glycosyltransferase activity in miniaturized assays

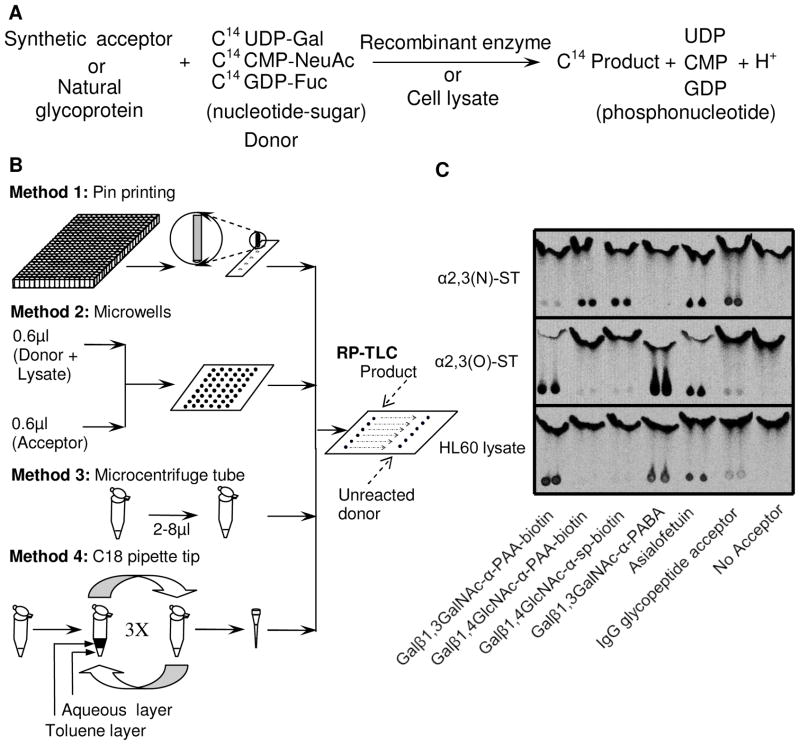

GlycoT reactions were performed using microarray pin printers to dispense radioactive material (~100 nL reaction volume), microwells fabricated using photolithography (~1 μL volume) and microcentrifuge tube based assays (2–8 μl) (Fig. 1A, 1B). Additionally, in some cases, C18 pipette tips were used to concentrate reaction products. Acceptors used for experiments are listed in Table 1. RP-TLC was employed in all cases to separate radiolabeled product from unreacted nucleotide-sugar. This enabled simultaneous quantification of both reactant and product concentrations. Phosphorimaging allowed detection of 14C radioactivity down to 4 dpm, and thus this was a sensitive method.

Figure 1.

A. Glycosyltransferase reactions Various synthetic or natural acceptors were mixed with radiolabeled nucleotide-sugars in the presence of recombinant enzymes or cell lysates. Unreacted donor was separated from product using reverse-phase thin layer chromatography (RP-TLC). Product concentration and unreacted donor amount were quantified using phosphorimaging. B. Experimental protocols. In Method 1, a microarrayer delivered ~100 nl of acceptor-donor mix to enzyme spots on slide. This method is well-suited for detecting high levels of enzyme activity. In Method 2, glycoT reactions were conducted in 1.2 μL volume in microwells. In Method 3, enzyme reactions were conducted in 2–8 μL volume in microcentrifuge tubes. Methods 2 and 3 are suitable for studies with cell lysates when enzyme activity is moderate. In Method 4, C18 pipette tips were used to concentrate the radioactive product. This is a suitable approach to quantify product formation when enzyme activity is low. C. RP-TLC and phosphorimaging. Following reaction, product was separated from unreacted donor using RP-TLC. All samples were run in duplicate. Phosphorimaging quantified extent of reaction. This method was suitable both for assays performed with cloned enzymes (α2,3(O)SialylT and α2,3(N)SialylT) and with cell lysates.

Table 1.

Acceptor list*

| Enzyme Class | GalT | SialylT | FucT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptors** | 5mM | 0.6mM | 1.5mM |

| GalNAcα-sp-biotin | β1,3GalT | ||

| GalNAcα-PABA | β1,3GalT | ||

| Galβ1,3GalNAcα-sp-biotin | ST3[Galβ1,3GalNAc] | ||

| Galβ1,3GalNAcα-PABA | ST3[Galβ1,3GalNAc] | ||

| Galβ1,4GlcNAcβ-sp-biotin | ST3/6[Galβ1,4GlcNAc] | ||

| Galβ1,4GlcNAcβ1,3Galβ1,4GlcNAcβ-O-Bn | ST3/6[Galβ1,4GlcNAc] | α1,3FucT | |

| Galβ1,4GlcNAcβ1,3Galβ-Φ-NO2 | α1,3FucT[LacNAc] | ||

| NeuAcα2,3Galβ1,4GlcNAcβ-PAA-biotin | α1,3FucT[SialylLacNAc] | ||

| Galβ1,3GlcNAcβ1,3lacβ-Φ-NO2 | ST3/6[Galβ1,3GlcNAc] | α1,2/4FucT | |

| GlcNAcβ1,6GalNAcα-sp-biotin | β1,3GalT, β1,4GalT | ||

| Galβ1,3(GlcNAcβ1,6)GalNAcα-sp- biotin | β1,4GalT | ||

| Galβ1,3(GlcNAcβ1,6)GalNAcα-O-Bn | β1,4GalT | ||

Acceptor concentrations for GalT (5mM), SialylT (0.6mM) and FucT (1.5mM) reactions exceed enzyme KM. Enzyme-activity/linkage-specificity are defined based on the composition of the expected product.

sp- = O(CH2)3NHCO(CH2)5NH-, PABA = p-amino benzoic acid, Bn = Benzyl, PAA = polyacrylamide, Φ-NO2 = p-nitrophenol.

As seen in the phosphorimaging result (Fig. 1C), RP-TLC separation was feasible for a range of acceptors including biotinylated acceptors with polyacrylamide and -(CH2)3NHCO(CH2)5NH- spacer groups, synthetic carbohydrates with 4-(para)-amino benzoic acid or benzyl groups, natural glycoproteins like asialofetuin and IgG glycopeptides. In all cases, the unreacted nucleotide-sugar moved with the front of the mobile phase while the radioactive product remained stationary. In the absence of acceptor (last lane, Fig. 1C), as expected, negligible product formation was detected. The assays could be performed using cloned α2,3(N)sialylT which prefers N-acetyl lactosamine (Galβ1,4GlcNAc) substrate (top row of Fig. 1C), and also α2,3(O)sialylT, which prefers to catalyze sialic acid addition to the Galβ1,3GalNAc arm of core-2 trisaccharide (middle row of Fig. 1C). The catalytic activity due to these enzymes are termed ST3[Galβ1,4GlcNAc] and ST3[Galβ1,3GalNAc] respectively. Also included in Fig. 1C (bottom row) are studies with HL-60 cell lysate. This cell line displays complex sialylT activity with predominant reactivity towards acceptors containing the Galβ1,3GalNAc structure.

Overall, the use of RP-TLC with phosphorimaging provides a rapid, quantitative and scalable method to measure glycoT enzyme activity using a broad set of synthetic and natural carbohydrate acceptors.

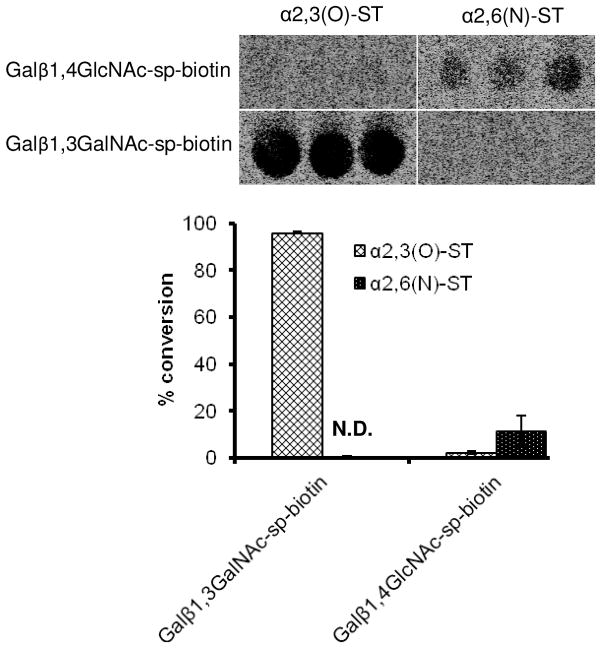

Pin-printing for enzymes with high specific activity

We examined the potential that the throughput of glycoT assays could be enhanced using a microarrayer (Fig. 2). To this end, 0.5 μL of recombinant rat α2,3(O)-ST and α2,6(N)-ST (i.e. sialyltransferase ST6Gal-I) were pipetted onto microscope slides. The SpotBot microarrayer was then used to place the reaction mixture containing acceptor and donor on the enzyme spot. The FPAM pins used in this step delivered 100±20 nL of fluid, based on independent radioactivity measurements. After 2 h reaction, product formation was quantified using RP-TLC. As expected based on an earlier study [32], recombinant α2,3(O)-sialylT was highly specific towards Galβ1-3GalNAc-α-sp-biotin while ST6Gal-I displayed high specificity towards Galβ1-4GlcNAc-α-sp-biotin.

Figure 2. Pin-printing.

0.6 mM Galβ1,3GalNAc-sp-biotin or 1.87 mM Galβ1,4GlcNAc-sp-biotin were mixed with 56.75 μM CMP-[14C]NeuAc in sialylT reaction buffer, and spotted on 0.28 U/mL recombinant sialyT (either α2,3(O)-ST or α2,6(N)-ST). After 2 h, product formed was separated using RP-TLC and % conversion was quantified using phosphorimaging data (top section). Each sample was run in triplicate. Only product formation at TLC origin is shown, i.e. mobile phase is not shown. N.D.: product not detected.

Microcentrifuge tubes and microwells for enzymes with moderate specific activity

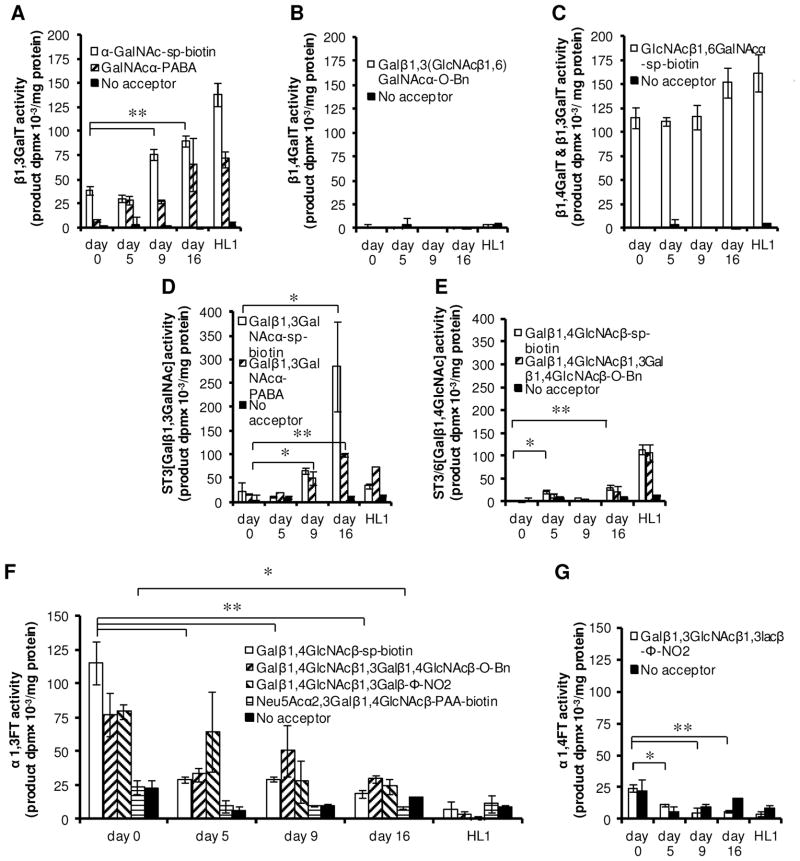

While the pin printing approach (Fig. 2) was straightforward when using recombinant enzymes with high specific activity, product formation in ~100 nL reaction volume was difficult to quantify when using cell lysates since the enzyme concentration and acceptor amount was low. This was overcome by performing GlycoT activity assays in 1.2–8 μL volume either in microwells or microcentrifuge tubes (Fig. 3). In all runs, product formation was quantified using RP-TLC and phosphorimaging as above.

Figure 3. GlycoT activity in mESCs.

Product formed at 8 h was quantified in ‘dpm/mg of protein in cell lysate’ for undifferentiated mESCs (day 0), and for differentiated cells at days 5, 9 and 16. Enzyme activity of terminally differentiated mESCs cells (day 16) were compared with that of HL1 cells. A–C. GalT activity. This activity was measured using acceptors with GalNAcα reactive groups for β1,3GalTs (panel A), Galβ1,3(GlcNAcβ1,6)GalNAcα-O-Bn epitope for β1,4GalT (panel B), and GlcNAcβ1,6GalNAcα-sp-biotin which detects both β1,3GalT and β1,4GalT activity (panel C). D–E. SialylT activity. Acceptors with Galβ1,3GalNAc reactive unit measured ST3[Galβ1,3GalNAc] activity (panel D) while ST3[Galβ1,4GlcNAc] activity was measured using acceptors containing the N-Acetyl lactosamine (LacNAc) unit, Galβ1,4GlcNAcβ. F–G. FucT activity. α1,3-FucT activity was measured using acceptors containing the LacNAc and sialyl-LacNAc unit (panel F). α1,2 and α1,4-FucT activity was measured using the acceptor Galβ1,3GlcNAcβ1,3lacβ-Φ-NO2. In all cases, the ‘no acceptor’ negative control runs measured enzyme activity in the absence of any acceptor. * and ** indicate p<0.05 and p<0.01, respectively.

Enzyme activity was quantified for mESCs that were either undifferentiated (day 0) or that were differentiated to cardiomyocytes over a 16–20 day time-course. ~50% of the cells were in beating foci by 16 days. The glycoT activity profile of the fully differentiated mESCs was compared to that of HL1 cells, a mouse atrial cardiomyocyte cell line. For cell samples collected on various days (day 0, 5, 9, 16), glycoT activity was assayed for members of the galT, fucT and sialylT families. Each biochemical reaction was conducted for either 1 h (Supplemental Fig. S1), 4 h (Supplemental Fig. S2), 8 h (Fig. 3) or 20 h (Supplemental Fig. S3). As enzymatic reactions proceed linearly over this time course (Supplemental Fig. S4), detailed analysis primarily considered the 8 h reaction data (Fig. 3).

Upon mESC differentiation, the overall activity of galTs (Fig. 3A–3C) and sialylTs (Fig. 3D–3E) increased in general, while the FucT activity (Fig. 3F–3G) decreased. Among the galTs, while the activity of β1,3GalT (measured using α-GalNAc-sp-biotin and GalNAc-α-PABA) increased sharply between day 5 and 9 (Fig. 3A), β1,4GalT activity was low at all times (Fig. 3B). Enzyme activity of day 16 differentiated cells quantitatively matched enzyme activities measured in HL1 cells (Fig. 3A–3C). In the case of the sialylTs, ST3[Galβ1,3GalNAc] activity markedly increased between day 5 and 9 (Fig. 3D). ST3[Galβ1,4GlcNAc] activity also increased upon differentiation though some fluctuation was apparent during the time course (Fig. 3E). These observations regarding the sialylTs were consistently noted using two independent acceptors for each enzyme activity. Among the fucTs, the α(1,3)fucT that acts on the LacNAc unit to create Lewis-X type structures decreased upon differentiation. The control HL1 cells displayed negligible fucT activity. α(1,2) and α(1,4)fucT activity was absent in mESCs and HL1 cells at all times (Fig. 3G). α(1,3)fucT activity towards the NeuAcα2,3Galβ1,4GlcNAc-β-PAA-biotin acceptor (Fig. 3F) was also negligible in these cells. This last enzyme activity is mediated by FucT-VII [33].

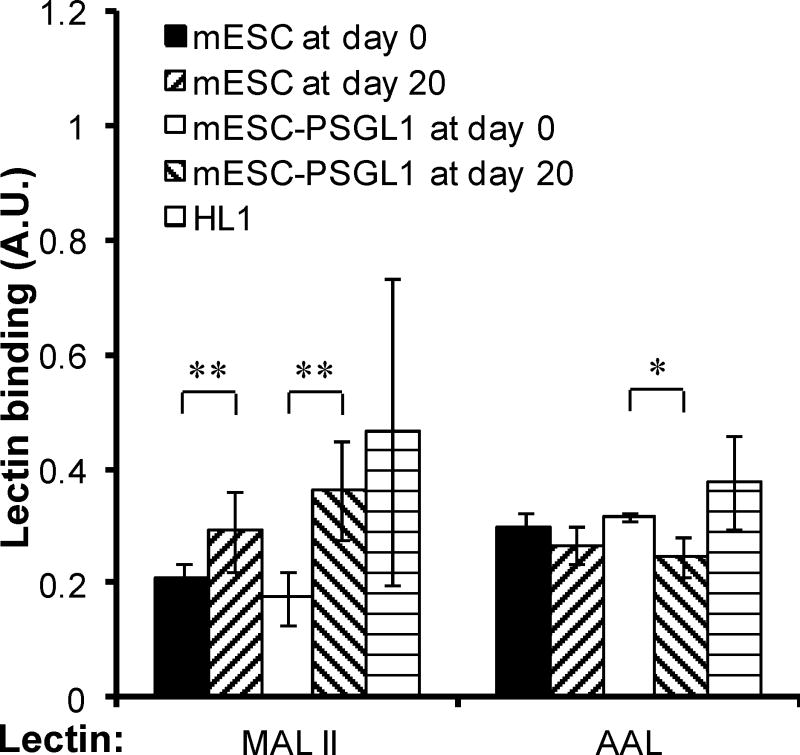

Relating enzyme activity changes to glycan structure alterations as measured using lectins

There is currently considerable interest to identify lectins that bind stage-specific antigens on stem cells as they can define unique markers of pluripotency. This includes investigations that utilize lectin-microarrays to test entire panels of reagents to determine which lectins differentially bind pluripotent cells compared to non-pluripotent cells [34; 35].

Motivated by these studies, we tested the possibility that changes in enzyme activity measured upon differentiation using the miniaturized assays may predict alterations in lectin binding affinity (Fig. 4). Specifically: (i) Since β(1,3)galT and ST3[Galβ1,3GalNAc] activity increase upon differentiation, we tested the possibility that the expression of NeuAcα2,3Galβ1,3GalNAc type epitopes is augmented in myocytes compared to mESCs. This epitope is recognized by the lectin MAL-II. (ii) Since α(1,3)fucosylation of acceptors with terminal LacNAc decrease upon differentiation, the binding of pan-fucose binding lectin AAL is likely to decrease. Such studies were performed with both wild-type mESCs and the same cells that over-express a human leukocyte glycoprotein called P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1). As expected based on the above hypotheses, MAL-II binding to differentiated myocytes at day 20 was higher and AAL binding to these cells was lower compared to mESCs (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Lectin staining of mESCs and differentiated mESCs.

Wild type mESCs and mESCs over-expressing human P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (mESC-PSGL1) were stained with biotinylated lectins (MAL-II and AAL) at either day-0 prior to differentiation, or at day-20 after differentiation to cardiomyocytes. HL1 cardiomyocytes were used as positive control. AAL binding decreased and MAL-II binding increased upon differentiation. * and ** indicate p<0.05 and p<0.01, respectively.

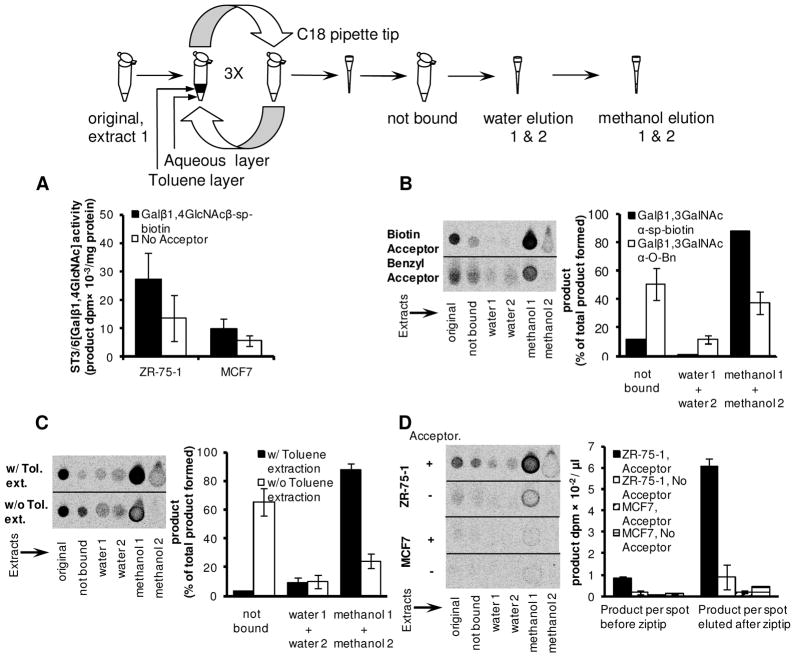

C18 pipette tips to concentrate reaction products

One limitation of the RP-TLC method is that only ~0.5–1 μL of the reaction product can be separated using this approach. While acceptable in most instances, strategies to enrich the reaction product can be beneficial when the extent of reaction is low. In such cases, the signal in runs with acceptors may not be very different from the no acceptor control. This is illustrated in Fig. 5A for two breast cancer cell lines, ZR-75-1 and MCF7. Here the ST3/6[Galβ1,4GlcNAc] activity of ZR-75-1 and MCF7 cells is between 1.5 to 2 times that of the no acceptor control. We determined if pipette tips packed with C18 matrix can be applied to enrich reaction products prior to RP-TLC since this can improve the signal/noise ratio.

Figure 5. Product concentration using C18 pipette tip. A. SialylT activity in breast cancer cells.

ST3[Galβ1,4GlcNAc] activity measured for ZR-75-1 and MCF-7 cells using Galβ1,4GlcNAc-sp-biotin as acceptor was only 1.5–2-fold greater than ‘no acceptor’ control. Reactions were performed in microwells and RP-TLC was used to quantify extent of reaction. GlycoT reaction proceeded for 8 h. B. Recombinant enzyme mediated reaction in the absence of detergent. Galβ1,3GalNAcα-sp-biotin and Galβ1,3GalNAcα-O-Bn were sialylated by recombinant α2,3(O)-sialylT. The original reaction product was analyzed using RP-TLC (‘original’). The reaction mixture was also diluted 2-fold and this was passed through a C18 pipette tip. Product that did not bind the C18 matrix was termed ‘not bound’. The pipette tip was then washed twice with 3 μL water and eluates were analyzed (‘water 1’ and ‘water 2’). Finally, the sample was eluted twice with 1 μL methanol (‘methanol 1’ and ‘methanol 2’). Each of the above fractions was analyzed using RP-TLC (see image). Histogram plot presents % of product eluted in each fraction based on radioactivity measurements. Biotinylated acceptor was superior to benzylated molecule in this assay. C. Effect of detergent. Experiments identical to panel B were performed using Galβ1,3GalNAc-sp-biotin and α2,3(O)-sialylT, only 0.2% Triton-X was added to the final product. C18 pipette tip separation and RP-TLC analysis was performed either with or without prior toluene-mediated solvent extraction. Workflow for experiment is shown in schematic. As seen, product binding to C18 matrix was partially inhibited by Triton-X, and solvent extraction effectively removes the detergent from the reaction mixture. D. Concentration of product when cell lysate is enzyme source. ST3[Galβ1,4GlcNAc] sialylT activity assays for ZR-75-1 and MCF-7 were performed as in panel A. Toluene-mediated solvent extraction and C18 tip concentration were performed to remove detergent prior to RP-TLC analysis. This procedure concentrated product by ~6-fold in the case of ZR-75-1. No enzyme activity was detected in MCF-7. Runs without acceptor serve as negative control.

Using Galβ1-3GalNAc-α-sp-biotin and Galβ1,3GalNAc-α-O-Bn, we illustrate that C18 pipette tips can enrich sialylated products formed by recombinant α2,3(O)-SialylT (Fig. 5B). As seen, while ~90% of the radioactive product was bound to the pipette tip in the case of the biotinylated acceptor, this percentage was lower at ~50% in the case of Galβ1,3GalNAc-α-O-Bn. Thus, this method is better suited for some acceptors compared to others. The weaker binding of the acceptor with the benzyl group was also evident in the water wash steps since 10% of the radioactive product was released in this case. Following water washes, elution with methanol resulted in near complete release of radiolabeled product for both acceptors. While RP-TLC was used to resolve unreacted sugar-nucleotide from radioactive product in the case of all fractions, we noted that the methanol eluate from the C18 tips had negligible amounts of sugar-nucleotide since this did not bind the C18 packing material. The sugar nucleotide in our study was primarily removed during the binding and water wash steps. Overall, product enrichment was possible both in the case of Galβ1,3GalNAc-α-sp-biotin and Galβ1,3GalNAc-α-O-Bn using the C18 tips.

When cell lysates are used as enzyme source, Triton-X present in the reaction mixture interferes with product binding to C18 (Fig. 5C). As this detergent prefers to partition in the organic phase, solvent extraction using toluene is a straightforward method to remove Triton-X. The acceptor, on the other hand, is only sparingly soluble in toluene. As shown in Fig. 5C, inclusion of a toluene solvent extraction step dramatically enhances the amount of radioactive product captured by the C18 tip when detergent is present in the reaction mixture. ~95% of the product was captures when a solvent extraction step was included whereas only 30% was bound in the absence of this. Further, ~85% of the radioactivity could be released with methanol when toluene-extraction was included.

Next, to resolve the ST3/6[Galβ1,4GlcNAc] activity in lysates of ZR-75-1 and MCF-7 (Fig. 5A), we determined if the use of toluene extraction along with C18 pipette tip can enhance the signal (Fig. 5D). As seen, a 6-fold enrichment of radioactive product was possible in the case of ZR-75-1 cells. Product formed using MCF-7 was negligible. Thus, we conclude that ST3/6[Galβ1,4GlcNAc] activity is present in ZR-75-1 but not MCF-7 cells.

Overall, the use of the C18 pipette tip allowed rapid enrichment of reaction product. Inclusion of a solvent extraction step is necessary if detergent is present in the reaction mixture. This assay strategy enables amplification of signal when enzyme activity is low.

DISCUSSION

Methodologies to miniaturize glycoT assays

This manuscript tests methods to reduce the size and increase the throughput of traditional glycoT assays. Radioactivity is preferred since this is a sensitive method that can detect signal in the pCi range. Unlike fluorescence that requires modification of the sugar-nucleotide (e.g. FITC [18] or Azido derivatization [19]), studies with radioactivity proceed with the natural, unmodified donor. Concerns regarding safety are addressed by confining most of the product and donor radioactivity to the solid-phase (RP-TLC plates). The RP-TLC separation method was also surprisingly robust for a wide range of synthetic acceptors carrying hydrophobic polyacrylamide-biotin, amino-benzoic acid, para-nitrophenol, and benzyl groups at the anomeric position, and also for various natural glycoproteins. To the extent tested, the method was insensitive to changes in the functional group at the anomeric position. The use of phosphorimaging allowed simultaneous, absolute quantitation of both unreacted donor and product amount. The method provided a linear signal over 4–5 orders of magnitude of radioactivity. Together, these straightforward and scalable methods circumvent the need for more complex column chromatography steps that are common to traditional glycoT assays [27; 32]. The methods presented, may thus find application in laboratories where chemical synthesis of carbohydrate acceptors is not a specialization.

The study shows that miniaturization of glycoT reactions below 1 μL is readily possible. While ~80,000 cells were used for typical reactions that proceeded in 1 μL volume, it is plausible that this number may be further reduced by additional optimization of the experimental methods. While most of the data are presented for reactions that proceeded for 2–8 h, use of glycerol and high relative humidity typically allowed reactions to proceed for >24 h with little sample evaporation. Studies with varying reaction volume that utilized cancer cell lysates as enzyme source demonstrate that the extent of reaction is invariant with reaction volume in the range from 1–20μL (Supplemental Figure S5). It is possible that the reaction volume may affect the absolute reaction rates in other experimental conditions and this is not ruled out based on Figure S5.

Among the methods tested, the microarray technique was ideally suited to quantify high levels of enzyme activity. The microwell and microcentrifuge tube assays were suitable for studies with cell lysates, though these may be further automated and scaled-down using non-contact printers [36]. The use of the C18 pipette tip method allowed enrichment of reaction products when enzyme activity was low. Inclusion of a solvent extraction step was necessary, here, if detergent was present in the reaction mixture.

Relating glycoT activity changes to glycan structure: A study using mESCs

There is interest in assaying or predicting changes in glycan structures during development and cancer. While such analysis can be performed using mass spectrometry, this technology is more suitable for ionizable species. Also, it can miss important structures that are expressed at relatively low abundance [37]. Studies of mRNA expression can reveal changes in the underlying glycoTs that contribute to glycan changes though the relation between mRNA levels and glycoT activity is highly non-linear [2]. The relation between mRNA expression and glycan structure changes is even more correlative, and thus transcript analysis alone cannot reliably predict glycosylation changes [38]. Unlike this, the relation between glycoT activity and glycan structure is semi-quantitative, at least in some systems [2], and thus the methods developed here are significant.

Our data suggest a transition from LeX type structures in native mESCs to sialylated Galβ1,3GalNAc type glycans as these cells differentiate to cardiomyocytes. In this regard, the GlycoT enzyme analysis reveals a prominent decrease in α(1,3)fucT activity towards LacNAc type structures as cells differentiate. This is consistent with a decrease in the expression of the stage specific embryonic antigen-1 (SSEA1, Galβ1,4[Fucαl,3]GlcNAcβ1-R) or LeX epitope that we [39] and others [40; 41] have reported upon loss of pluripotency. Also noted in our study is a decrease in AAL lectin binding upon differentiation. An abrogation of AAL lectin binding is not observed because this reagent recognizes additional terminal fucose residues in addition to those linked via α1,3 bonds. Using FUT9−− mice, Kudo et al. [42], show that this activity in mice is likely due to the α(1,3)fucT FUT9 which acts to create the LeX antigen in mouse embryonic lineages. In addition to a decrease in α(1,3)fucT activity, we also report an increase in β(1,3)galT and ST3[Galβ1,3GalNAc] sialylT activity. The NeuAcα2,3Galβ1,3GalNAc type glycans formed as a result were recognized by the lectin MAL-II. Whether this structure is expressed on O-glycans, N-glycans or glycolipids remains to be determined.

While only minor enzyme activity changes were observed as mESCs were differentiated in suspension as EBs between day 1–5, a more prominent change was apparent between day 5–9, when these cells further advanced towards cardiomyocytes as monolayers on gelatin. In this regard, both the change in culture protocol from suspension-based to substrate-adherent, and the directed nature of the differentiation protocol in the latter phase likely contribute to this observation. Consistent with the idea that glycan changes are modest during the initial phase, are mass spectrometry results that demonstrate the presence of substantial amounts of N-linked glycans with high mannose, hybrid and bi-antennary structures in both mESC and EB stages [43]. Transcript levels of glycosylation related genes are also only altered nominally when mESCs differentiate in EBs [44]. Further, a modest increase in biantennary and triantennary structures, and the extent of terminal sialylation is noted at the EB stage [43], and this is consistent with our observation of increased α(2,3)sialylation. We are not aware of similar analysis of glycans after the EB stage. Nevertheless, it is reported that glycan structures change in myocytes as neonatal cells evolve to adult, and glycosylation of particular myocyte ion channels may regulate cellular contractility [45]. Whether the enzymatic changes measured in this study contribute to functional consequences remains to be determined. Future work will also determine if glycan changes associated with the measured enzyme activity can be applied to enrich particular sub-populations of cells, e.g. the beating cardiomyocytes. Finally, while the current study differentiates mESCs down the cardiac mesoderm lineage, additional work is needed to determine if the pattern of enzyme activity changes is different when cells differentiate towards ectoderm and endoderm germ layer progeny.

Overall, the current study developed miniaturized assay techniques that can be used to study both recombinant enzymes and cell lysates. By studying a range of enzymes (galTs, fucTs and sialylTs), we attempt to demonstrate the potential wide applicability of the described methodologies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a NY state stem cell grant C024282 (SN), and NIH grants HL63014 (SN), CA121294 (KLM), HL092398 (EST) and HL103709 (EST).

ABBREVIATIONS

- glycoT

glycosyltransferase

- LacNAc

N-Acetyllactosamine

- Galβ1, 3GalNAc

Type-III or core-1 type acceptors

- Galβ1, 4GlcNAc

Type II or LacNAc type chain

- GalT

galactosyltransferase

- FucT

fucosyltransferase

- SialylT

sialyltransferase

- ST3[Galβ1,3GalNAc]

α2,3SialylT acting on Galβ1,3GalNAc

- ST3/6[Galβ1,4GlcNAc]

α2,3 or α2,6 SialylT acting on Galβ1,4GlcNAc

- α1,3FucT[LacNAc]

α1,3FucT activity towards LacNac

- α1,3FucT[SialylLacNAc]

α1,3FucT activity towards NeuAcα2,3Galβ1,4GlcNAc

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Varki A, Cummings RD, Esko JD, Freeze HH, Stanley P, Bertozzi CR, Hart GW, Etzler ME. Essentials of glycobiology. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor: 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marathe DD, Chandrasekaran EV, Lau JT, Matta KL, Neelamegham S. Systems-level studies of glycosyltransferase gene expression and enzyme activity that are associated with the selectin binding function of human leukocytes. FASEB J. 2008;22:4154–67. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-104257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wirtz D, Konstantopoulos K, Searson PC. The physics of cancer: the role of physical interactions and mechanical forces in metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:512–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc3080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muramatsu T, Muramatsu H. Carbohydrate antigens expressed on stem cells and early embryonic cells. Glycoconj J. 2004;21:41–5. doi: 10.1023/B:GLYC.0000043746.77504.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Viswanathan K, Chandrasekaran A, Srinivasan A, Raman R, Sasisekharan V, Sasisekharan R. Glycans as receptors for influenza pathogenesis. Glycoconj J. 2010;27:561–70. doi: 10.1007/s10719-010-9303-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandrasekaran EV, Xue J, Neelamegham S, Matta KL. The pattern of glycosyl- and sulfotransferase activities in cancer cell lines: a predictor of individual cancer-associated distinct carbohydrate structures for the structural identification of signature glycans. Carbohydr Res. 2006;341:983–994. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandrasekaran E, Xue J, Piskorz C, Locke R, Tóth K, Slocum H, Matta K. Potential tumor markers for human gastric cancer: an elevation of glycan:sulfotransferases and a concomitant loss of α1,2-fucosyltransferase activities. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2007;133:599–611. doi: 10.1007/s00432-007-0206-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nairn AV, Kinoshita-Toyoda A, Toyoda H, Xie J, Harris K, Dalton S, Kulik M, Pierce JM, Toida T, Moremen KW, Linhardt RJ. Glycomics of proteoglycan biosynthesis in murine embryonic stem cell differentiation. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:4374–87. doi: 10.1021/pr070446f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abbott KL, Nairn AV, Hall EM, Horton MB, McDonald JF, Moremen KW, Dinulescu DM, Pierce M. Focused glycomic analysis of the N-linked glycan biosynthetic pathway in ovarian cancer. Proteomics. 2008;8:3210–20. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng C, Chen RR. A pH-sensitive assay for galactosyltransferase. Anal Biochem. 2004;330:219–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Persson M, Palcic MM. A high-throughput pH indicator assay for screening glycosyltransferase saturation mutagenesis libraries. Anal Biochem. 2008;378:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wongkongkatep J, Miyahara Y, Ojida A, Hamachi I. Label-free, real-time glycosyltransferase assay based on a fluorescent artificial chemosensor. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:665–8. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee HS, Thorson JS. Development of a universal glycosyltransferase assay amenable to high-throughput formats. Anal Biochem. 2011;418:85–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzgerald DK, Colvin B, Mawal R, Ebner KE. Enzymic assay for galactosyl transferase activity of lactose synthetase and alpha-lactalbumin in purified and crude systems. Anal Biochem. 1970;36:43–61. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(70)90330-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu ZL, Ethen CM, Prather B, Machacek M, Jiang W. Universal phosphatase-coupled glycosyltransferase assay. Glycobiology. 2011;21:727–33. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwq187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Houseman BT, Mrksich M. Carbohydrate arrays for the evaluation of protein binding and enzymatic modification. Chem Biol. 2002;9:443–54. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00124-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park S, Shin I. Carbohydrate microarrays for assaying galactosyltransferase activity. Org Lett. 2007;9:1675–1678. doi: 10.1021/ol070250l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blixt O, Allin K, Bohorov O, Liu X, Andersson-Sand H, Hoffmann J, Razi N. Glycan microarrays for screening sialyltransferase specificities. Glycoconj J. 2008;25:59–68. doi: 10.1007/s10719-007-9062-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hang HC, Yu C, Pratt MR, Bertozzi CR. Probing glycosyltransferase activities with the Staudinger ligation. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:6–7. doi: 10.1021/ja037692m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donovan RS, Datti A, Baek MG, Wu Q, Sas IJ, Korczak B, Berger EG, Roy R, Dennis JW. A solid-phase glycosyltransferase assay for high-throughput screening in drug discovery research. Glycoconj J. 1999;16:607–615. doi: 10.1023/a:1007024916491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baker CA, Poorman RA, Kezdy FJ, Staples DJ, Smith CW, Elhammer AP. A Scintillation Proximity Assay for UDP-GalNAc:Polypeptide,N-Acetylgalactosaminyltransferase. Anal Biochem. 1996;239:20–24. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hood CM, Kelly VA, Bird MI, Britten CJ. Measurement of [alpha](1–3)Fucosyltransferase Activity Using Scintillation Proximity. Anal Biochem. 1998;255:8–12. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyashiro M, Furuya S, Sugita T. A high-throughput screening system for [alpha]1–3 fucosyltransferase-VII inhibitor utilizing scintillation proximity assay. Anal Biochem. 2005;338:168–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahsen Ov, Voigtmann U, Klotz M, Nifantiev N, Schottelius A, Ernst A, Muller-Tiemann B, Parczyk K. A miniaturized high-throughput screening assay for fucosyltransferase VII. Anal Biochem. 2008;372:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Northen TR, Lee JC, Hoang L, Raymond J, Hwang DR, Yannone SM, Wong CH, Siuzdak G. A nanostructure-initiator mass spectrometry-based enzyme activity assay. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3678–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712332105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanchez-Ruiz A, Serna S, Ruiz N, Martin-Lomas M, Reichardt NC. MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometric Analysis of Enzyme Activity and Lectin Trapping on an Array of N-Glycans. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011 doi: 10.1002/anie.201006304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chandrasekaran EV, Xue J, Xia J, Locke RD, Matta KL, Neelamegham S. Reversible sialylation: synthesis of cytidine 5′-monophospho-N-acetylneuraminic acid from cytidine 5′-monophosphate with alpha2,3-sialyl O-glycan-, glycolipid-, and macromolecule-based donors yields diverse sialylated products. Biochemistry. 2008;47:320–30. doi: 10.1021/bi701472g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Claycomb WC, Lanson NA, Jr, Stallworth BS, Egeland DB, Delcarpio JB, Bahinski A, Izzo NJ., Jr HL-1 cells: a cardiac muscle cell line that contracts and retains phenotypic characteristics of the adult cardiomyocyte. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:2979–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jing D, Parikh A, Tzanakakis ES. Cardiac cell generation from encapsulated embryonic stem cells in static and scalable culture systems. Cell Transplant. 2010;19:1397–412. doi: 10.3727/096368910X513955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geisler C, Jarvis DL. Effective glycoanalysis with Maackia amurensis lectins requires a clear understanding of their binding specificities. Glycobiology. 2011;21:988–93. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwr080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsumura K, Higashida K, Ishida H, Hata Y, Yamamoto K, Shigeta M, Mizuno-Horikawa Y, Wang X, Miyoshi E, Gu J, Taniguchi N. Carbohydrate binding specificity of a fucose-specific lectin from Aspergillus oryzae: a novel probe for core fucose. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:15700–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701195200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chandrasekaran EV, Xue J, Xia J, Chawda R, Piskorz C, Locke RD, Neelamegham S, Matta KL. Analysis of the specificity of sialyltransferases toward mucin core 2, globo, and related structures. identification of the sialylation sequence and the effects of sulfate, fucose, methyl, and fluoro substituents of the carbohydrate chain in the biosynthesis of selectin and siglec ligands, and novel sialylation by cloned alpha2,3(O)sialyltransferase. Biochemistry. 2005;44:15619–35. doi: 10.1021/bi050246m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Natsuka S, Gersten KM, Zenita K, Kannagi R, Lowe JB. Molecular cloning of a cDNA encoding a novel human leukocyte alpha-1,3-fucosyltransferase capable of synthesizing the sialyl Lewis x determinant. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16789–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang YC, Nakagawa M, Garitaonandia I, Slavin I, Altun G, Lacharite RM, Nazor KL, Tran HT, Lynch CL, Leonardo TR, Liu Y, Peterson SE, Laurent LC, Yamanaka S, Loring JF. Specific lectin biomarkers for isolation of human pluripotent stem cells identified through array-based glycomic analysis. Cell Res. 2011;21:1551–63. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tateno H, Toyota M, Saito S, Onuma Y, Ito Y, Hiemori K, Fukumura M, Matsushima A, Nakanishi M, Ohnuma K, Akutsu H, Umezawa A, Horimoto K, Hirabayashi J, Asashima M. Glycome diagnosis of human induced pluripotent stem cells using lectin microarray. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:20345–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.231274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wong EY, Diamond SL. Enzyme microarrays assembled by acoustic dispensing technology. Anal Biochem. 2008;381:101–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zaia J. Mass spectrometry and glycomics. Omics. 2010;14:401–18. doi: 10.1089/omi.2009.0146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nairn AV, York WS, Harris K, Hall EM, Pierce JM, Moremen KW. Regulation of glycan structures in animal tissues: transcript profiling of glycan-related genes. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17298–313. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801964200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kehoe DE, Lock LT, Parikh A, Tzanakakis ES. Propagation of embryonic stem cells in stirred suspension without serum. Biotech Prog. 2008;24:1342–1352. doi: 10.1002/btpr.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kannagi R, Nudelman E, Levery SB, Hakomori S. A series of human erythrocyte glycosphingolipids reacting to the monoclonal antibody directed to a developmentally regulated antigen SSEA-1. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:14865–14874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kannagi R, Cochran NA, Ishigami F, Hakomori S, Andrews PW, Knowles BB, Solter D. Stage-specific embryonic antigens (SSEA-3 and -4) are epitopes of a unique globo-series ganglioside isolated from human teratocarcinoma cells. EMBO J. 1983;2:2355–61. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1983.tb01746.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kudo T, Kaneko M, Iwasaki H, Togayachi A, Nishihara S, Abe K, Narimatsu H. Normal Embryonic and Germ Cell Development in Mice Lacking {alpha}1,3-Fucosyltransferase IX (Fut9) Which Show Disappearance of Stage-Specific Embryonic Antigen 1. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4221–4228. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4221-4228.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alvarez-Manilla G, Warren NL, Atwood J, 3rd, Orlando R, Dalton S, Pierce M. Glycoproteomic analysis of embryonic stem cells: identification of potential glycobiomarkers using lectin affinity chromatography of glycopeptides. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:2062–75. doi: 10.1021/pr8007489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nairn AV, Kinoshita-Toyoda A, Toyoda H, Xie J, Harris K, Dalton S, Kulik M, Pierce JM, Toida T, Moremen KW, Linhardt RJ. Glycomics of Proteoglycan Biosynthesis in Murine Embryonic Stem Cell Differentiation. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:4374–4387. doi: 10.1021/pr070446f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Montpetit ML, Stocker PJ, Schwetz TA, Harper JM, Norring SA, Schaffer L, North SJ, Jang-Lee J, Gilmartin T, Head SR, Haslam SM, Dell A, Marth JD, Bennett ES. Regulated and aberrant glycosylation modulate cardiac electrical signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16517–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905414106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.