Abstract

Recent scientific and technological innovations have produced an abundance of potential markers that are being investigated for their use in disease screening and diagnosis. In evaluating these markers, it is often necessary to account for covariates associated with the marker of interest. Covariates may include subject characteristics, expertise of the test operator, test procedures or aspects of specimen handling. In this paper, we propose the covariate-adjusted receiver operating characteristic curve, a measure of covariate-adjusted classification accuracy. Nonparametric and semiparametric estimators are proposed, asymptotic distribution theory is provided and finite sample performance is investigated. For illustration we characterize the age-adjusted discriminatory accuracy of prostate-specific antigen as a biomarker for prostate cancer.

Some key words: Classification accuracy, Covariate effect, Receiver operating characteristic curve, Sensitivity, Specificity

1. Introduction

Research into new markers for disease diagnosis, screening and prognosis has exploded in recent years. The primary question in each setting is of classification accuracy: how well does the marker distinguish between the two groups of individuals, the ‘cases’ and the ‘controls’?

The receiver operating characteristic or roc curve plays a central role in evaluating classification accuracy (Baker, 2003; Pepe et al., 2001). Let D denote the binary group variable such as disease status, and let YD and YD̄ denote case and control marker observations with survivor functions SD(y) = pr(YD > y) and SD̄ = pr(YD̄ > y). The roc curve is a plot of the true-positive fraction or sensitivity versus the false-positive fraction or 1-specificity for rules that classify an individual as ‘test-positive’ if Y > c, where the threshold c varies over all possible values. Equivalently, if the false-positive fraction is t, then the receiver operating characteristic curve is (Pepe, 2003, p. 69).

There are often factors, such as patient or disease characteristics or features of the specimen handling or test procedure, which affect the marker and its associated classification accuracy. These effects may mean that the definition of testing positive on the basis of the marker should depend on covariates, or that the accuracy of the test is less than optimal in certain settings (Pepe, 2003, pp. 48–9). This paper proposes a covariate-adjusted summary of classification accuracy, the covariate-adjusted roc curve.

2. The covariate-adjusted roc curve

Let Y be a continuous marker and let Z be a covariate. The methods generalize naturally to multiple covariates. Let ZD and ZD̄ denote case and control covariate observations with cumulative distribution functions PD and PD̄. Denote by SD(y | z) = pr(YD > y | ZD = z) and SD̄ (y | z) = pr(YD̄ > y | ZD̄ = z) the continuous survivor functions for Y conditional on Z = z, where and are the inverse conditional survivor functions, and let fD(y | z) and fD̄ (y | z) be the conditional densities.

The covariate-adjusted roc curve at a false-positive fraction of t is the overall true-positive fraction when thresholds for defining ‘test-positive’ are covariate-specific, chosen to ensure that the value of the false-positive fraction is t in each covariate-specific population. Mathematically, we write , where we note that the threshold equal to the quantile yields a false-positive fraction of t in the covariate-specific population. Naturally, the marginal false-positive fraction is also equal to t.

The covariate-specific receiver operating characteristic curve, is the roc curve for the marker in the population with covariate level Z = z. Interestingly, the adjusted roc can be written as a weighted average of covariate-specific curves,

| (1) |

Equivalently, aroc(t) = E{roc(t | ZD)}, where the expectation is taken with respect to ZD. Equation (1) shows that when Z affects marker observations but not discriminatory accuracy as defined by the roc curve, the adjusted roc is the common covariate-specific roc curve; it is perhaps best motivated in this setting. On the other hand, when Z affects discrimination, the adjusted roc reports a weighted average of covariate-specific true-positive fractions, holding the covariate-specific false-positive fractions constant. While estimation of covariate-specific roc curves is typically of primary interest in this context, the adjusted roc curve is a summary of covariate-adjusted accuracy that is useful for comparing markers and in small studies where covariate-specific roc curves cannot be estimated with precision.

Another interpretation follows from noting that aroc(t) = pr{SD̄ (YD | ZD) ⩽ t}, the cumulative distribution function of SD̄ (YD | ZD), where SD̄ (YD | ZD) is the placement of a case observation relative to a reference distribution for controls with the same covariate value. Contrast this with the unadjusted or pooled roc curve which has been shown to be equal to the cumulative distribution function of a case observation standardized relative to the general control distribution (Pepe & Cai, 2004), roc(t) = pr{SD̄ (YD) ⩽ t}.

Expression (1) has some attractive mathematical properties, including invariance with respect to monotone increasing transformations of Y and/or Z. It is also unaffected by control covariate-dependent sampling. This follows because such designs sample controls randomly conditional on Z, and cases randomly marginally. Janes & Pepe (2008) argue for its use in studies that employ frequency matching, where controls are sampled to have the same distribution of Z as cases. This is one type of covariate-dependent sampling.

3. Estimation

3.1. Estimators

We propose two estimators for using nD and nD̄ case and control observations. In both instances, the outside probability is estimated empirically. With the nonparametric estimator, valid for a discrete covariate Z ∈ {1, . . . , K}, we estimate the quantiles empirically in each covariate stratum. With the semiparametric estimator, the quantiles are estimated based on a model for YD̄ as a function of ZD̄. We lay out the general framework for the adjusted roc estimator, of which the nonparametric estimator is a special case.

We assume the quantile model YD̄ = f (ZD̄, ∊; θ), where ∊ is random error and θ are parameters. With the semiparametric adjusted roc estimator, this model may be parametric, such as a normal linear model, or semiparametric (Heagerty & Pepe, 1999). Let be the function which extracts the 1 − t quantile from the set of control quantiles with covariate value Z = z. We write

With the nonparametric estimator, are the quantiles themselves, , and , all estimated using nD̄(z) observations in each covariate stratum. This estimator depends only on the ranks of the data, and thus is invariant with respect to monotone transformations.

3.2. Asymptotic distribution theory

We make the following assumptions in establishing asymptotic distribution theory. Recall that the distribution of YD is not a function of θ.

Assumption 1. We assume that observations are randomly sampled conditional on D, that nD + nD̄ → ∞ and that nD/nD̄ → λ ∈ (0, 1).

Assumption 2. We assume that converges in distribution to a normal zero-mean random variable with covariance matrix Σθ as nD̄ → ∞.

Assumption 3. We assume that arocθ(t) is differentiable, and hence continuous, in θ.

Assumption 4. We assume that limnD̄ → ∞pr{arocθ̂(t) ∉ {0, 1}} = 1, where arocθ̂(t)= pr{YD > q(t; ZD, θ̂) | θ̂} is the adjusted roc based on estimated quantiles.

Assumption 5. We assume that t ∉ {0, 1}.

In relation to Assumption 1, covariate-dependent sampling can also be accommodated; see § 3.4. A wide variety of quantile models satisfy Assumption 2, including parametric models (Cole, 1990; Cole & Green, 1992; Pepe, 2003, p. 140), semiparametric models (Heagerty & Pepe, 1999; Zheng & Heagerty, 2004), empirical methods, as proven in the Appendix, and any θ̂ based on unbiased estimating equations satisfying standard regularity conditions. Assumption 3 is also valid for a diversity of quantile and roc models, such as the location-scale quantile model (Heagerty & Pepe, 1999) with bounded (∂/∂t) roc(t | z) and E(ZD) < ∞; see an unpublished University of Washington technical report by H. Janes and M. S. Pepe, available at http://www.bepress.com/uwbiostat/paper283. Assumption 4 is violated if the support for YD is entirely above or below the estimated quantile of interest. This will not occur as long as the support for YD includes the support for YD̄ or if the support for YD is unbounded, as under the normal distribution. We also require that t ∉ {0, 1}, but by definition aroc(0) = 0 and aroc(1) = 1. Finally, imposing continuity of SD(y | z) and SD̄ (y | z) implies that roc(t | z) and aroc(t) are continuous in t. The proof of the following theorem is given in the Appendix.

Theorem 1. Under Assumptions 1–5, converges in distribution to a normal zero-mean random variable with variance V(t) as nD, nD̄ → ∞, where

| (2) |

The form of V(t) is intuitively plausible. The second component comes from estimating the Z-specific quantiles, while the first is a binomial variance associated with estimating the true-positive fraction, given the quantiles.

For the nonparametric estimator, Assumptions 2 and 3 are satisfied when the following assumption holds.

Assumption 6. We assume that fD̄(y | z) is continuous and positive in a neighbourhood of for all z.

Under Assumptions 1–6, V(t) reduces to

| (3) |

where pD and pD̄ are the probability mass functions for ZD and ZD̄; see the Appendix for a proof.

3.3. Consistent variance estimation

Our first variance estimator can be used to estimate the variance of the semiparametric adjusted roc estimator, namely expression (2) multiplied by . The semiparametric estimator is consistent by Theorem 1. We assume that a consistent estimator of Σθ exists; for example, if θ̂ is based on a set of unbiased estimating equations, a sandwich-type variance estimator can be used. The jth component of (∂/∂θ) arocθ(t) is estimated by (arôcθ̂+hj(n) − arôcθ̂−hj(n))/{2h(n)}, where h(n) is , and θ̂ + hj(n), respectively θ̂ − hj (n), denotes the vector θ̂ with h(n) added to, respectively subtracted from, the jth component only. In the Appendix, the composite variance estimator is shown to be consistent under Assumptions 1–5 and the following Assumption 7.

Assumption 7. We assume that

for all j.

With small sample sizes, the estimate of (∂/∂θj) arocθ(t) may be sensitive to the choice of bandwidth, h(n). We have used h(n) = 0.04 in applications and simulations; this value ensured that (arocθ+hj(n) − arocθ−hj(n))/{2h(n)} ≃ (∂/∂θj) arocθ(t) in one example and has worked well in practice. We leave exploration of the optimal choice of h(n) for future research.

Our second variance estimator can be used to estimate the variance of the nonparametric estimator, namely expression (3) multiplied by . Here, arocθ(t) is estimated using the non-parametric estimator, pD and pD̄ by binomial proportions, empirically, and fD(y | z) and fD̄ (y | z) with uniformly consistent kernel density estimators (Silverman, 1986, § 3.7). In the Appendix we prove that the composite function is consistent under Assumptions 1–6 and the following Assumption 8.

Assumption 8. We assume that fD(y | z) and fD̄ (y | z) are continuous density functions for all z.

Bootstrap variance estimation is a simple alternative which accommodates clustered sampling as well as performing well in practice and in simulations; see § 4.

3.4. Sampling based on covariates

In many situations, sampling may depend on both D and Z. Two examples of this are frequency matching and sampling subjects in a specified range of Z. Our asymptotic results hold under such designs, but all population distributions should be replaced with sampling distributions.

3.5. Estimation using roc regression

The aroc can also be estimated using the roc regression method of Pepe (2000) and Alonzo & Pepe (2002), which requires estimation of covariate-specific control quantiles and specifying and fitting a model for the roc curve, typically as a function of covariates. A model for the adjusted roc curve is obtained by including Z in the quantile calculations, while omitting Z from the roc model. A classic example is the binormal model, aroc(t) = Φ{α + βΦ−1(t)}, where Φ is the standard normal cumulative distribution function. This approach results in a smooth parametric estimate of the adjusted roc, but the marker distributions remain unspecified. The semiparametric roc regression estimator of Cai & Pepe (2002) reduces to our semiparametric estimator.

4. Small sample performance

We evaluate the finite sample properties of our estimators using simulations, starting with the nonparametric estimator and its variance which can be used for discrete Z. We assume that there exists a monotone increasing transformation under which Y is normally distributed conditional on a binary covariate, Z, in both cases and controls: YD̄ ∼ N (0, 1) and YD ∼ N (0.9, 1) conditional on Z = 0; YD̄ ∼ N (0.2, 1) and YD ∼ N (0.9, 1) conditional on Z = 1; pr(ZD̄ = 1) = 0.7 and pr(ZD = 1) = 0.3. All of the assumptions laid out in § 3 are satisfied under this model. The values of aroc(t) at t = 0.05, 0.10, 0.20 and 0.50 are 0.21, 0.33, 0.50 and 0.80 and the two components of asymptotic variance are (0.33, 0.44, 0.50, 0.32) and (1.41, 1.40, 1.14, 0.40).

We simulated 5000 datasets, where nD = nD̄ varies between 100 and 1000; see Table 1. In terms of percentage bias, defined as 100[avg{arôcθ̂(t)} − arocθ(t)]/arocθ(t), where avg{arôcθ̂(t)} is the average estimate, the estimator performs very well, except for some modest bias when both t and nD = nD̄ are small. The percentage bias in the nonparametric variance estimator, based on rectangular kernel density estimates, is , where the median is calculated because of the skewed distribution of the variance estimates, and vâr{arôcθ̂(t)} is the sample variance of the estimates. The variance estimator tends to underestimate the true variance. There is substantial bias when t is small, mostly due to estimation of the second component of variance, but this disappears for larger t. The percentage difference between the asymptotic and sample variances, , tends to be small, with differences only when both t and nD = nD̄ are small. Coverage probabilities using nonparametric variance estimators are provided. Coverage based on logit transformations, which have been shown to improve coverage for the pooled roc when t is close to 0 or 1 (Pepe, 2003, p. 102), are also shown. Only logit-based coverage is shown when both t and nD = nD̄ are small, as adjusted roc estimates are close to zero. We find that coverage can be low for small t but is very good for moderate t.

Table 1.

Small sample performance of the nonparametric estimator of the adjusted roc based on 5000 simulations. The sample size, nD = nD̄, varies between 100 and 1000. The nonparametric variance estimator uses rectangular kernel density estimates. Results are shown at four false-positive fractions of interest. Only coverage based on logit-transformations is shown for small t and nD = nD̄, since arôcθ̂(t) is frequently close to zero. Bootstrap variance estimates based on 100 bootstrap samples and associated coverage are also shown

| nD | % Bias | % Diff | % Bias var | Cov | Logit cov | % Bias Boot var | Cov | Logit cov |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t = 0.05 | ||||||||

| 100 | 6.15 | 21.34 | −30.65 | – | 89.36 | −25.25 | – | 87.32 |

| 200 | 10.05 | 7.83 | −29.67 | – | 88.14 | −6.30 | – | 91.68 |

| 500 | 2.40 | 6.88 | −20.25 | – | 91.58 | 4.36 | – | 94.86 |

| 1000 | 1.71 | 2.28 | −16.24 | 91.90 | 92.14 | 2.92 | 94.40 | 94.18 |

| t = 0.10 | ||||||||

| 100 | 7.83 | 15.48 | −19.75 | – | 91.22 | −7.32 | – | 93.38 |

| 200 | 4.37 | 7.06 | −17.53 | – | 91.88 | 0.79 | – | 94.82 |

| 500 | 0.75 | 3.88 | −12.94 | – | 93.22 | 2.27 | – | 94.60 |

| 1000 | 0.94 | 1.39 | −10.53 | 92.86 | 92.18 | 1.68 | 94.10 | 94.40 |

| t = 0.20 | ||||||||

| 100 | 2.21 | 12.70 | −4.42 | 91.92 | 95.36 | 1.04 | 93.88 | 97.08 |

| 200 | 1.45 | 6.64 | −6.00 | 92.76 | 94.38 | 3.08 | 94.26 | 95.68 |

| 500 | 0.24 | 3.51 | −3.96 | 93.74 | 94.42 | 2.96 | 94.44 | 95.08 |

| 1000 | 0.33 | 4.26 | −1.12 | 94.14 | 94.42 | 5.04 | 94.16 | 94.56 |

| t = 0.50 | ||||||||

| 100 | 0.02 | 2.05 | −3.67 | 92.16 | 96.98 | 8.41 | 95.00 | 97.26 |

| 200 | −0.11 | −0.10 | −0.47 | 93.42 | 95.86 | 4.38 | 94.18 | 95.98 |

| 500 | −0.05 | −1.23 | 1.78 | 94.78 | 95.98 | 0.71 | 94.64 | 95.42 |

| 1000 | −0.01 | 2.48 | 6.37 | 95.36 | 95.88 | 3.76 | 94.78 | 95.20 |

% Bias, percentage bias in arocθ(t); % Diff, percentage difference between asymptotic and sample variances; % Bias var, percentage bias in the nonparametric variance estimator; Cov, coverage of 95% confidence intervals; Logit cov, coverage based on logit-transformations; Boot var, bootstrap variance estimates.

We also evaluate the performance of bootstrap variance estimates. Data are resampled 100 times conditional on D, and the sample variance of the adjusted roc estimates is calculated. The bootstrap variance estimator exhibits substantially less bias than the nonparametric estimator. Bootstrap coverage also tends to be better; coverage is good except when both t and nD = nD̄ are small.

Table 2 compares the nonparametric estimator of the adjusted roc with the semiparametric estimator based on a normal linear quantile model. The percentage difference in the estimates, defined as avg{arôcθ̂;semi(t) − arôcθ̂(t)}/arocθ(t), where arôcθ̂(t) is the nonparametric estimator and arôcθ̂;semi(t) is the semiparametric estimator, tends to be small. The estimated relative efficiency of the two estimators, vâr{arôcθ̂;semi(t)}/vâr{arôcθ̂(t)}, where the variances are estimated from the 5000 simulations, shows that the semiparametric estimator yields substantial gains in efficiency, with larger gains for smaller t and larger nD = nD̄.

Table 2.

Comparison of the nonparametric and semiparametric estimates of the adjusted roc based on 5000 simulations. The sample size, nD = nD̄, varies between 100 and 1000. The semiparametric estimator uses a normal linear quantile model. The percentage difference in the adjusted roc estimates and relative efficiency are shown at four false-positive fractions of interest

| t = 0.05 | t = 0.10 | t = 0.20 | t = 0.50 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nD | % Diff | re | % Diff | re | % Diff | re | % Diff | re |

| 100 | −0.20 | 0.61 | −5.33 | 0.68 | −2.24 | 0.76 | −0.75 | 0.82 |

| 200 | −6.87 | 0.54 | −2.98 | 0.64 | −1.25 | 0.72 | −0.33 | 0.81 |

| 500 | −1.90 | 0.51 | −0.88 | 0.61 | −0.47 | 0.71 | −0.17 | 0.79 |

| 1000 | −0.92 | 0.50 | −0.52 | 0.61 | −0.12 | 0.71 | −0.04 | 0.82 |

% Diff, percentage difference in the adjusted roc estimates; re, relative efficiency.

The performances of the semiparametric estimator and its variance are explored under the double binormal model; see Lin & Jeon (2003) and the authors’ technical report. Under this model, there is a monotone increasing transformation under which (Y, Z) is bivariate normal in both cases and controls. We set the parameter values to E(YD̄) = E(ZD̄) = 0, E(YD) = 0.7, E(ZD) = 0.5, var(YD̄) = var(YD) = 1, var(ZD̄) = var(ZD) = 1.52, corr(YD, ZD) = 0.6 and corr(YD̄, ZD̄) = 0.2. This is an extension of the classic binormal model for the pooled roc curve (Swets, 1986; Hanley, 1988, 1996). The induced adjusted roc is a binormal roc curve, as shown in the authors’ technical report. All of the assumptions laid out in § 3 are satisfied under this model. We apply the semiparametric estimator using a normal linear quantile model; this is the true model for YD̄ given ZD̄. The values of aroc(t) at t = 0.05, 0.10, 0.20 and 0.50 are 0.16, 0.25, 0.39 and 0.67. The two components of asymptotic variance are (0.24, 0.37, 0.49, 0.36) and (0.35, 0.53, 0.56, 0.23).

We simulated 5000 datasets, in which nD = nD̄ varies between 100 and 1000. The estimator performs very well, except for some modest bias for very small nD = nD̄ and t ; see Table 3. The semiparametric variance estimator exhibits moderate small sample bias for the smallest sample sizes; the variance is consistently overestimated. This is primarily due to bias in the second component of variance, which involves (∂/∂θ) arocθ(t). However, coverage is reasonable. The asymptotic and sample variances agree quite well, except for some minor differences with the smallest sample sizes. Bootstrap variance estimates are good alternatives: they tend to exhibit less bias and have excellent coverage.

Table 3.

Small sample performance of the semiparametric estimator of the adjusted roc based on 5000 simulations. The sample size, nD = nD̄, varies between 100 and 1000. The quantiles are estimated using a normal linear model, and the semiparametric variance estimator uses a bandwidth of h = 0.04. Results are shown at four false-positive fractions of interest. Only coverage based on logit transformations is shown for small t and nD = nD̄, since arôcθ̂(t) is frequently close to zero. Bootstrap variance estimates based on 100 bootstrap samples and associated coverage are also shown

| nD | % Bias | % Diff | % Bias var | Cov | Logit cov | % Bias Boot var | Cov | Logit cov |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t = 0.05 | ||||||||

| 100 | 14.35 | −7.64 | 1.50 | – | 91.52 | 6.25 | – | 93.20 |

| 200 | 6.47 | 0.28 | 5.17 | – | 93.88 | 6.67 | – | 94.64 |

| 500 | 2.97 | 0.21 | 3.70 | – | 94.60 | 1.97 | – | 95.40 |

| 1000 | 0.85 | 1.64 | 1.95 | 94.32 | 95.08 | 2.20 | 94.42 | 95.30 |

| t = 0.10 | ||||||||

| 100 | 7.08 | 2.27 | 8.25 | – | 93.30 | 2.47 | – | 94.96 |

| 200 | 3.23 | 3.26 | 4.87 | – | 94.28 | 3.79 | – | 95.48 |

| 500 | 1.34 | −2.22 | −2.72 | – | 94.22 | −3.09 | – | 94.82 |

| 1000 | 0.34 | 2.47 | 1.48 | 94.66 | 95.10 | 2.48 | 95.00 | 95.44 |

| t = 0.20 | ||||||||

| 100 | 2.46 | 5.14 | 9.02 | 92.54 | 94.02 | −0.12 | 93.50 | 95.86 |

| 200 | 1.26 | 2.31 | 4.54 | 93.80 | 94.70 | 0.25 | 94.38 | 95.54 |

| 500 | 0.37 | −0.55 | −0.26 | 94.10 | 95.42 | −1.71 | 94.30 | 94.72 |

| 1000 | 0.03 | −0.33 | 0.79 | 94.48 | 94.72 | −0.17 | 94.42 | 94.66 |

| t = 0.50 | ||||||||

| 100 | −0.62 | 3.66 | 13.89 | 93.52 | 95.98 | 9.06 | 94.70 | 96.76 |

| 200 | −0.44 | 1.08 | 9.75 | 94.58 | 95.44 | 4.63 | 94.92 | 95.68 |

| 500 | −0.21 | 1.38 | 5.50 | 95.02 | 95.26 | 4.35 | 94.82 | 95.18 |

| 1000 | −0.14 | 0.45 | 3.13 | 95.00 | 95.24 | 3.24 | 94.68 | 94.88 |

% Bias, percentage bias in arocθ(t); % Diff, percentage difference between asymptotic and sample variances; % Bias var, percentage bias in the nonparametric variance estimator; Cov, coverage of 95% confidence intervals; Logit cov, coverage based on logit-transformations; Boot var, bootstrap variance estimates.

5. Illustration

Data from the Physicians’ Health Study (Gann et al., 1995) are used for illustration. This was a randomized controlled study of aspirin and β-carotene among 22 071 U.S. male physicians of ages 40 to 84 years in 1982. A blood sample taken at enrolment was stored. For 429 men diagnosed with prostate cancer up to 12 years after enrolment, most before PSA, Prostate-Specific Antigen, was widely used for screening, and for 1287 controls not diagnosed with prostate cancer during 12 years of follow-up, the serum was assayed for PSA. Cases and controls were matched on age; for each case, three controls within one year of age were selected (Gann et al., 1995; Etzioni et al., 2004).

The goal of this sub-study is to assess the ability of PSA to discriminate between men who did and did not develop prostate cancer. The pooled roc curve in the matched data is not of practical interest (Janes & Pepe, 2008). It describes the ability of PSA to distinguish between cases and age-matched controls, an artificial control group. More importantly, this curve is attenuated by the matching on age. We use the adjusted roc to quantify the age-adjusted classification accuracy of PSA.

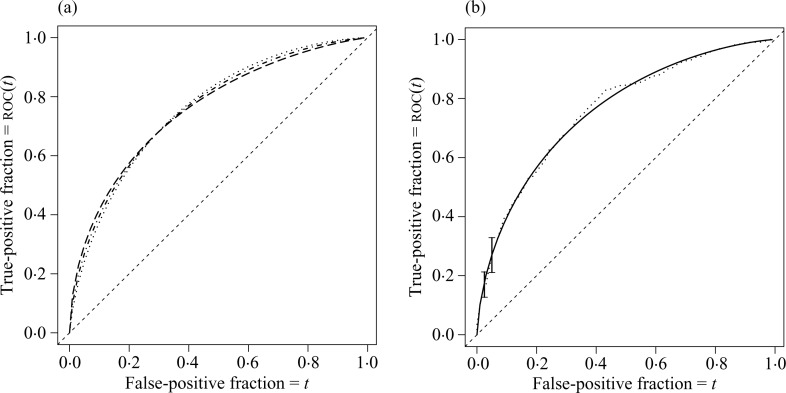

Age-specific roc curves for PSA, estimated using a binormal roc regression model (Alonzo & Pepe, 2002) with quantiles from a linear location-scale model (Heagerty & Pepe, 1999), reveal very little variation in discrimination due to age; see Fig. 1(a). Hence, the adjusted roc represents the common age-specific roc curve for PSA.

Fig. 1.

roc curves for PSA in the Physicians’ Health Study data. (a) Age-specific roc curves, 50 (dotted), 60 (dash-dotted), 70 (dashed), estimated using the roc regression model. (b) The age-adjusted roc curve, estimated using the semiparametric estimator (the dotted line) and the roc regression model (the solid line). The 95% confidence intervals, based on bootstrapped variance estimates, are overlaid at t = 0.025 and t = 0.05.

The adjusted roc for PSA is shown in Fig. 1(b), estimated using both the semiparametric estimator and a binormal roc regression model, where the control quantiles are estimated using a linear location-scale model (Heagerty & Pepe, 1999) for both methods. Bootstrapping is used for inference, and logit-based confidence intervals for the semiparametric estimator are overlaid at t = 0.025 and t = 0.05. The curve describes the ability of PSA to discriminate between cases and controls of the same age. We estimate that when the age-specific false-positive fraction is held at 0.025, 17% of cases can be detected, with a 95% confidence interval of 13% to 21%. When the common false-positive fraction is increased to 0.05, 27% of cases can be detected, with a 95% confidence interval of 21% to 33%.

6. Discussion

When covariates affect discrimination, there are various ways of combining covariate-specific roc curves. The adjusted roc curve is a simple vertical average. A horizontal average may be more appropriate in certain settings, and is a simple extension of our methods.

The area under the adjusted roc, equivalent to pr(YD > YD̄ | ZD = ZD̄), can be interpreted as the probability of correctly ordering a randomly chosen case and a control observation with the same covariate value. This statistical summary deserves further development and may be used to compare covariate-adjusted roc curves for different markers.

Acknowledgments

We thank Meir Stampfer for providing the data for the illustration. This paper was supported by funding from the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Appendix

Proof of Theorem 1. We write

Note that , and by Assumptions 1–3, the delta method (Ferguson, 1996, p. 45) and Slutsky’s theorem, Bn converges in distribution to a normal zero-mean random variable with variance matrix

Now, we write , and find its asymptotic distribution conditional on θ̂, using the Lindeberg–Feller central limit theorem. First, note that E(Ani | θ̂) = 0 and var(Ani | θ̂) = arocθ̂(t){1 − arocθ̂(t)}. Convergence under the Lindeberg–Feller central limit theorem requires that

| (A1) |

converges to zero as nD → ∞ for all ∊ > 0. However, takes the value {1 − arocθ̂(t)}2I {arocθ̂(t)−1 ⩽ ∊nD} with probability arocθ̂(t), and arocθ̂(t)2I [{1 − arocθ̂(t)}−1 ⩽ ∊nD] with probability 1 − arocθ̂(t). Hence, (A1) becomes

Assumptions 4 and 5 ensure that this converges to zero. Thus, conditional on θ̂, An [arocθ̂(t){1 − arocθ̂(t)}]−1/2 converges in distribution to a standard normal random variable as nD → ∞. Finally, the asymptotic distribution of An [arocθ̂(t){1 − arocθ̂(t)}]−1/2 conditional on θ̂ is the same as that of An [arocθ̂(t){1 − arocθ̂(t)}]−1/2 conditional on Bn, since it is functionally independent of θ̂ and . By Assumptions 2 and 3, arocθ̂(t){1 − arocθ̂(t)} converges in probability to arocθ(t){1 − arocθ(t)} as nD̄ → ∞. By Slutsky’s theorem,

converges in distribution to a zero-mean bivariate normal random variable with covariance matrix

as nD, nD̄ → ∞. The continuous mapping theorem then yields the desired result.

Nonparametric estimation of aroc(t)

We prove that Assumptions 2 and 3 are satisfied with empirical quantile estimators. Under Assumption 6, by standard empirical process theory (Ferguson, 1996, p. 91), for a fixed stratum Z = z and conditional on nD̄(z), converges in distribution to a normal zero-mean random variable with variance . By Assumption 1, converges in probability to pD̄(z) as nD̄ → ∞. Hence, for all ∊, there exists N such that

Since nD̄(z) → ∞, the second term can be made arbitrarily small, and pr{nD̄(z) > N} arbitrarily close to 1, by choosing N large enough. Thus, converges in distribution to a normal zero-mean random variable with variance , and by Slutsky’s theorem, converges in distribution to a normal zero-mean random variable with variance as nD̄ → ∞. Since observations in different strata are independent, marginal convergence implies joint asymptotic normality, with the variance-covariance matrix . We also calculate the form of(∂/∂θ)arocθ(t). We have

and V(t) reduces to (3).

Consistency of the semiparametric variance estimator

We write the estimator of (∂/∂θj) arocθ(t) as

| (A2) |

Consider the first component. We claim that converges in distribution to a normal zero-mean random variable with variance V(t). The proof of this fact is similar to the proof that is asymptotically normal, and hence Op(1), as proven earlier. Hence, in probability since the denominator converges to ∞. A similar argument can be used to prove that the third term in (A2) converges to 0. Finally, {arocθ+hj(n)(t) − arocθ−hj(n)(t)}/{2h(n)} converges in probability to (∂/∂θj)arocθ(t) by continuity of arocθ(t) in θ; see Assumption 3. Hence, our estimator of (∂/∂θj) arocθ(t) is consistent. Now, with Σ^θ converging in probability to Σθ, arôcθ̂(t) converging in probability to arocθ(t) and consistency of the derivative estimator, we have consistency of the composite variance estimator.

Consistency of the nonparametric variance estimator

We have p̂D(z) converging in probability to pD(z) and p̂D̄(z) converging in probability to pD̄(z) for z = 1, . . . , K, and, by standard empirical process theory (Ferguson, 1996, p. 91) and Assumption 6, converges in probability to as nD̄ → ∞. We write

The first term converges in probability to zero by the uniform consistency of f̂D(y | z), while the second term converges in probability to zero by the consistency of , Assumption 8 and the continuous mapping theorem. Hence, converges in probability to as nD, nD̄ → ∞. A similar argument shows that is also consistent. The variance estimator is a continuous function of these components, and under Assumption 6 it is consistent.

References

- Alonzo TA, Pepe MS. Distribution-free ROC analysis using binary regression techniques. Biostatistics. 2002;3:421–32. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/3.3.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker S. The central role of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves in evaluating tests for the early detection of cancer. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2003;95:511–5. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.7.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai T, Pepe MS. Semi-parametric ROC analysis to evaluate biomarkers for disease. J Am Statist Assoc. 2002;97:1099–107. [Google Scholar]

- Cole TJ. The LMS method for constructing normalized growth standards. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1990;44:45–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole TJ, Green PJ. Smoothing reference centile curves: the LMS method and penalized likelihood. Statist Med. 1992;11:1305–19. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780111005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etzioni R, Falcon S, Gann PH, Kooperberg CL, Penson DF, Stampfer MJ. Prostate-specific antigen and free prostate-specific antigen in the early detection of prostate cancer: do combination tests improve detection? Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2004;13:1640–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson TS. A Course in Large Sample Theory. London: Chapman and Hall; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gann PH, Hennekens CH, Stampfer MJ. A prospective evaluation of plasma prostate-specific antigen for detection of prostatic cancer. J Am Med Assoc. 1995;273:289–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley JA. The robustness of the ‘binormal’ assumptions used in fitting ROC curves. Med. Decis. Making. 1988;8:197–203. doi: 10.1177/0272989X8800800308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley JA. The use of the ‘binormal’ model for parametric ROC analysis of quantitative diagnostic tests. Statist Med. 1996;15:1575–85. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960730)15:14<1575::AID-SIM283>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heagerty P, Pepe MS. Semi-parametric estimation of regression quantiles with application to standardizing weight for height and age in U.S. children. Appl Statist. 1999;48:533–51. [Google Scholar]

- Janes H, Pepe MS. Matching in studies of classification accuracy: implications for bias, efficiency, and assessment of incremental value. Biometrics. 2008;64:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Jeon Y. Discriminant analysis through a semi-parametric model. Biometrika. 2003;90:379–92. [Google Scholar]

- Pepe MS. An interpretation for the ROC curve and inference using GLM procedures. Biometrics. 2000;56:352–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe MS. The Statistical Evaluation of Medical Tests for Classification and Prediction. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pepe MS, Cai T. The analysis of placement values for evaluating discriminatory measures. Biometrics. 2004;60:528–35. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2004.00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe MS, Etzioni R, Feng Z, Potter JD, Thompson ML, Thornquist M, Winget M, Yatsui Y. Phases of biomarker development for early detection of cancer. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1054–61. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.14.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman BW. Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis. London: Chapman and Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Swets JA. Indices of discrimination or diagnostic accuracy: their ROCs and implied methods. Psychol Bull. 1986;99:100–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, Heagerty PJ. Semiparametric estimation of time-dependent ROC curves for longitudinal marker data. Biostatistics. 2004;5:615–32. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxh013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]