EGFR requires ADAM17 activity to preserve skin barrier homeostasis.

Abstract

ADAM17 (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase 17) is ubiquitously expressed and cleaves membrane proteins, such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) ligands, l-selectin, and TNF, from the cell surface, thus regulating responses to tissue injury and inflammation. However, little is currently known about its role in skin homeostasis. We show that mice lacking ADAM17 in keratinocytes (A17ΔKC) have a normal epidermal barrier and skin architecture at birth but develop pronounced defects in epidermal barrier integrity soon after birth and develop chronic dermatitis as adults. The dysregulated expression of epidermal differentiation proteins becomes evident 2 d after birth, followed by reduced transglutaminase (TGM) activity, transepidermal water loss, up-regulation of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-36α, and inflammatory immune cell infiltration. Activation of the EGFR was strongly reduced in A17ΔKC skin, and topical treatment of A17ΔKC mice with recombinant TGF-α significantly improved TGM activity and decreased skin inflammation. Finally, we show that mice lacking the EGFR in keratinocytes (EgfrΔKC) closely resembled A17ΔKC mice. Collectively, these results identify a previously unappreciated critical role of the ADAM17–EGFR signaling axis in maintaining the homeostasis of the postnatal epidermal barrier and suggest that this pathway could represent a good target for treatment of epidermal barrier defects.

The epidermis functions to create a barrier to protect from water loss and exclude foreign substances and microorganisms. It consists of a multilayered stratified epithelium with viable basal, spinous, and granular layers and a dead cornified layer (stratum corneum). The epidermal barrier is maintained and continuously regenerated by terminally differentiating keratinocytes, in a highly organized process called cornification (Candi et al., 2005). After the proliferating basal keratinocytes detach from the underlying basement membrane, they are committed to terminal differentiation and form the cornified layer, which consists of flattened cell remnants (corneocytes) surrounded by insoluble lipids. These detached suprabasal keratinocytes undergo several transcriptional and morphological changes during their translocation to the skin surface. Although these morphogenetic changes during epidermal stratification are well documented, the molecular processes of terminal differentiation, which are crucial for the development and homeostasis of the epidermal barrier, are not well understood (Blanpain and Fuchs, 2009).

The cornification process of granular keratinocytes begins with the formation of the cornified envelope (CE), an insoluble protein structure which is stabilized by trans-glutaminases (TGMs). It replaces the plasma membrane and functions as a scaffold for the attachment of insoluble lipids (Candi et al., 2005). The TGMs 1 and 3 are responsible for the characteristic resistance and insolubility of the CE because they cross-link its structural components like involucrin, loricrin, filaggrin, and the small proline-rich proteins. Specifically, the cytosolic TGM3 cross-links various CE components into small oligomers, which are then translocated and cross-linked onto the growing CE at the cell periphery by the membrane-bound TGM1 (Hitomi, 2005). A well balanced equilibrium of corneocyte differentiation and their controlled release from the skin surface (desquamation) is crucial to maintain the epidermal barrier and ensure its renewal every 3 wk (Blanpain and Fuchs, 2009). The physiological relevance of both TGMs in skin is highlighted by the lethality of Tgm1−/− and Tgm3−/− mice (Kim et al., 2002).

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is most prominently expressed in proliferating basal keratinocytes and to a lesser degree in suprabasal keratinocytes. It supports basal keratinocyte proliferation and delays apoptosis in suprabasal keratinocytes that have lost their interaction with the matrix (Pastore and Mascia, 2008; Pastore et al., 2008; Schneider et al., 2008). EGFR deficiency causes defects in hair follicle development and immature epidermal differentiation with inflammatory skin reactions (Miettinen et al., 1995; Murillas et al., 1995; Sibilia and Wagner, 1995; Threadgill et al., 1995; Sibilia et al., 2003), and anti-EGFR therapy in cancer patients commonly induces dermatologic side effects including xerotic itchy skin (Lacouture, 2006). Although these observations corroborate the significance of EGFR signaling in skin homeostasis, little is currently known about the role of EGFR signaling in maintaining the epidermal barrier and in suppressing chronic inflammatory skin disease.

ADAM17 (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase 17) is a membrane-anchored metalloproteinase that is a crucial upstream regulator of EGFR signaling (Peschon et al., 1998; Jackson et al., 2003; Sternlicht et al., 2005) and is responsible for the cleavage of pro-TNF (Black et al., 1997; Moss et al., 1997). Mice lacking ADAM17 die at birth, presumably as a result of defects in heart development, although other organs, such as the lung, skin, and mammary epithelia were also affected (Peschon et al., 1998; Jackson et al., 2003; Sternlicht et al., 2005). In that respect, Adam17−/− mice nearly phenocopy Egfr−/− mice or mice lacking the EGFR ligands TGF-α, HB-EGF, or amphiregulin, indicating an in vivo relevance of ADAM17 in EGFR processing (Peschon et al., 1998; Jackson et al., 2003; Blobel, 2005; Sternlicht et al., 2005). This notion is supported by cell-based assays, in which the shedding of several EGFR ligands depended on ADAM17 (Sahin et al., 2004). Moreover, ADAM17-dependent EGFR activation protects hepatocytes from apoptosis during drug-induced toxicity (Murthy et al., 2010) and supports intestinal proliferative regeneration in experimental colitis (Chalaris et al., 2010). Because very little is currently known about the role of ADAM17 in postnatal epithelial barrier homeostasis under physiological conditions, the goal of this study was to analyze how conditional inactivation of ADAM17 in keratinocytes (A17ΔKC) affects the development and maintenance of the epidermal barrier.

RESULTS

Keratinocyte-specific ADAM17 deficiency results in severe postnatal epidermal barrier defects

To analyze the function of ADAM17 in skin, we crossed mice with floxed alleles of ADAM17 (Horiuchi et al., 2007) with keratin14-Cre knockin mice (Krt14-Cre) to generate mice lacking ADAM17 in keratinocytes (A17ΔKC). Western blot analysis confirmed the deletion of ADAM17 in epidermal splits from A17ΔKC mice (Fig. 1 A). An analysis of the expression pattern of Krt14-Cre using the ROSA26-lacZ reporter confirmed that it was restricted to the squamous epithelia of the skin and mucosa, as previously reported (Wang et al., 1997; not depicted).

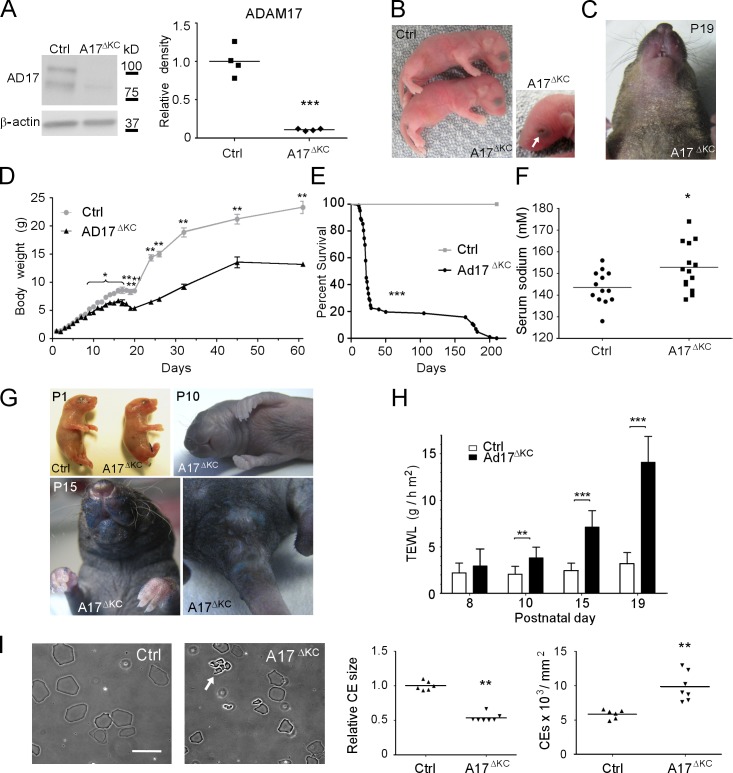

Figure 1.

Keratinocyte-specific ADAM17 deficiency results in postnatal epidermal barrier defects. (A) Western blot analysis to detect ADAM17 in lysates from P3 epidermal splits of control (Ctrl) or A17ΔKC mice. (B) Newborn A17ΔKC mice and their littermate controls. 7.5% of A17ΔKC newborn mice had open eyes at birth, indicated by arrow. (C) Dry scaly skin of A17ΔKC mice at P19. (D) Body weight of A17ΔKC versus control mice at different ages (n ≥ 4). (E) Survival curve of A17ΔKC mice (n = 100) versus controls (Ctrl, n = 25). Mantel-Cox test: ***, P < 0.001. (F) Serum sodium concentration of A17ΔKC versus control mice between P15 and P25. (G) Toluidine blue dye penetration assays were performed with newborn mice (P1), P10, and P15 animals indicating outside-in barrier defects (n = 3 per age group). Blue staining of the umbilical cord and the cut tail at P1 is a positive control. (H) TEWL in A17ΔKC and control littermates at P8, P10, P15, and P19 (n ≥ 4 for P8; n ≥ 8 for P10, P15, and P19). (I) Preparation of CEs from 25-mm2 P15 back skin samples. CE clustering is indicated by the arrow. Results: mean ± SD. Student’s t test: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Bar, 20 µm.

Newborn A17ΔKC mice had no evident skin defects (Fig. 1 B) or histological abnormalities in their epidermis (not depicted). About 7.5% of A17ΔKC mice were born with open eyes (Fig. 1 B), whereas all Adam17−/− mice (complete knockout) have open eyes at birth (Peschon et al., 1998; Horiuchi et al., 2007), suggesting that other cells besides keratinocytes contribute to this phenotype in Adam17−/− mice. However, starting at P19, macroscopic epidermal defects became evident, with dry scaly skin in the face, the area surrounding the snout, the ventral neck and chest (Fig. 1 C), and the tail (not depicted), suggesting a compromised epidermal barrier in A17ΔKC mice.

Epidermal barrier defects lead to water loss, weight loss, electrolyte imbalances, and loss of skin turgor (Shwayder and Akland, 2005). Although the Mendelian distribution of the offspring of Adam17flox/wt/Krt14-Cre × Adam17flox/flox mice was normal (not depicted) and A17ΔKC mice had a normal weight compared with littermate controls at birth and the first days thereafter, their weight was reduced by 5% at postnatal day 8 (P8) and ∼30% at P20 (Fig. 1 D). Most of the A17ΔKC mice died between P21 and P29, although some lived up to 6 mo (Fig. 1 E). The mean weight of surviving A17ΔKC mice was about half that of control animals (Fig. 1 D). Moreover, A17ΔKC mice had reduced skin turgor and significantly increased serum sodium levels (Fig. 1 F). The combination of hypernatremia and weight loss suggested dehydration as the underlying cause. None of the other genotypes (Adam17wt/wt/Krt14-Cre, Adam17flox/wt/Krt14-Cre, Adam17flox/wt, or Adam17flox/flox, referred to as Ctrl) displayed any evident phenotype (unpublished data). Together, these data suggest that the postnatal lethality in A17ΔKC mice was caused by water loss as the result of an epidermal barrier defect that developed after birth.

We next used a dye penetration assay to examine the integrity of the skin barrier. The epidermis of newborn mice and P10 pups was completely resistant to toluidine blue penetration, whereas P15 animals showed dye permeability in the mechanically stressed areas, including the face around their snout, genitals, anus, and paws (Fig. 1 G). Transepidermal water loss (TEWL) of the skin surface was first detectable at P10, and subsequently increased with age, as documented at P15 and P19 (Fig. 1 H), indicating severe inside-out barrier defects. Because epidermal lipids are crucial to form the protective barrier against water loss in the stratum corneum, we stained P15 skin sections with the lipophilic dye Nile red. No significant differences in epidermal lipid content and distribution were seen in A17ΔKC versus control mice (unpublished data). Impaired integrity of the CE has been linked to skin barrier defects (Sevilla et al., 2007). CE preparations derived from P15 biopsies of A17ΔKC back skin showed 50% reduced size and were clustered in conglomerates that were not seen in preparations of control skin (Fig. 1 I), indicating abnormal development and an immature state.

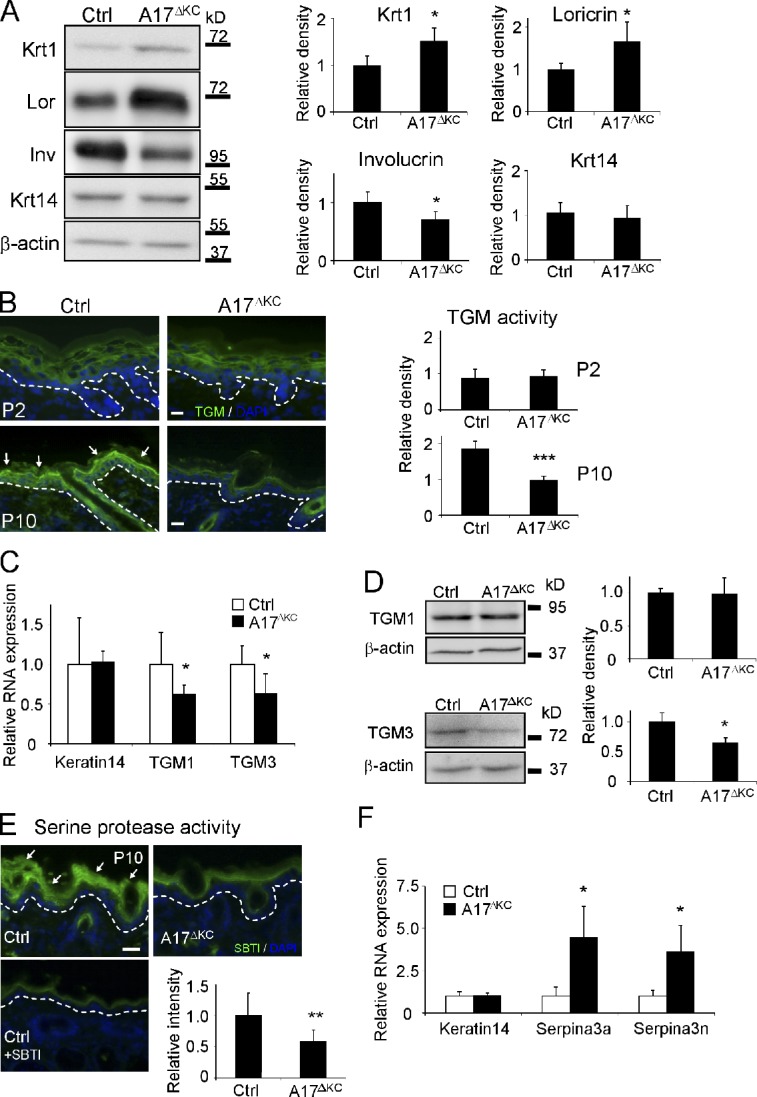

Dysregulated epidermal differentiation markers and decreased TGM activity in A17ΔKC skin

Skin integrity depends on the renewal of terminally differentiated keratinocytes, which assemble the CE. Histological analysis of back skin from A17ΔKC mice and littermate controls at P2 failed to uncover evident structural defects within the epidermal layers or differences in the number of proliferating basal keratinocytes (unpublished data). In contrast, epidermal differentiation was significantly altered, with increased production of the early differentiation marker keratin1 and the terminal differentiation marker loricrin, a major component of the CE (Koch et al., 2000), and decreased production of involucrin and TGM3, which are needed to initiate cornification on the skin surface, whereas the expression of keratin 14, a structural component of the basal layer, remained unchanged (Fig. 2 A). Thus, epidermal ADAM17 deficiency increases early and dysregulates late keratinocyte differentiation.

Figure 2.

Decreased TGM activity and altered expression of epidermal differentiation markers in A17ΔKC skin. (A) Western blots of epidermis lysates analyzing epidermal keratin1, keratin14, loricrin, and involucrin expression in A17ΔKC skin (quantification: n = 5). (B) In situ detection of TGM activity in A17ΔKC and control epidermis at P2 and P10, with TGM activity in the stratum granulosum of control epidermis indicated by arrows (quantification: n = 6). (C) Quantitative RT-PCR from total RNA of P10 A17ΔKC skin analyzing TGM1, TGM3, and keratin14 (n = 4). (D) Quantitative immunoblot analysis from P10 skin lysates analyzing TGM1 and TGM3 in A17ΔKC animals (n = 4). (E) Detection of serine protease activity in P10 skin with SBTI Alexa Fluor 488 conjugates in the stratum granulosum and stratum corneum in control skin (arrows) and in A17ΔKC skin (n = 3). The negative controls with an excess of unlabeled SBTI resulted in diminished signals. (F) RT-PCR analysis from total RNA derived from P10 skin for serpina3a, serpina3n, and keratin14 (n = 4). The dashed lines in B and E represent the basement membrane. Bars, 20 µm. Results: mean ± SD. Students t test: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

The TGMs 1 and 3 are crucial to forming the CE (Hitomi, 2005). When we used a fluorometric in situ assay with a synthetic TGM substrate (Raghunath et al., 1998) to evaluate whether the TGM expression or activity was altered in A17ΔKC keratinocytes, we found comparable epidermal TGM activity to control littermates at P2 but significantly reduced activity in A17ΔKC epidermis at P10 (Fig. 2 B). Moreover, quantitative RT-PCR analysis revealed similar expression of both TGMs at P2 (not depicted) but significantly reduced expression at P10 in A17ΔKC skin compared with controls (Fig. 2 C). An immunoblot of P10 skin showed significant reduction of TGM3 in A17ΔKC animals but comparable TGM1 levels (Fig. 2 D). Finally, there was a thickened stratum corneum (not depicted) and elevated CE numbers in A17ΔKC skin (Fig. 1 I, right), similar to the hyperkeratotic stratum corneum with significantly improved TEWL found in TGM1−/− skin grafts on nude mice as a compensatory mechanism for the skin permeability defects (Kuramoto et al., 2002).

Thickening of the cornified layer can be caused by reduced desquamation of corneocytes, which depends on processing by kallikreins (Eissa and Diamandis, 2008). When we probed A17ΔKC skin sections with fluorescently labeled soybean protease inhibitor (SBTI), which binds kallikreins (Franzke et al., 1996), we found significantly reduced staining in the A17ΔKC stratum corneum at P10 (Fig. 2 E). This indicates a strong reduction of serine protease activities, which can be caused by decreased protease expression or increased expression of inhibitors. A skin DNA microarray from P10 skin of A17ΔKC animals showed up-regulation of two serine protease inhibitors, serpina3a and a3n, compared with controls, which was confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 2 F).

Dysregulated terminal differentiation in A17ΔKC skin

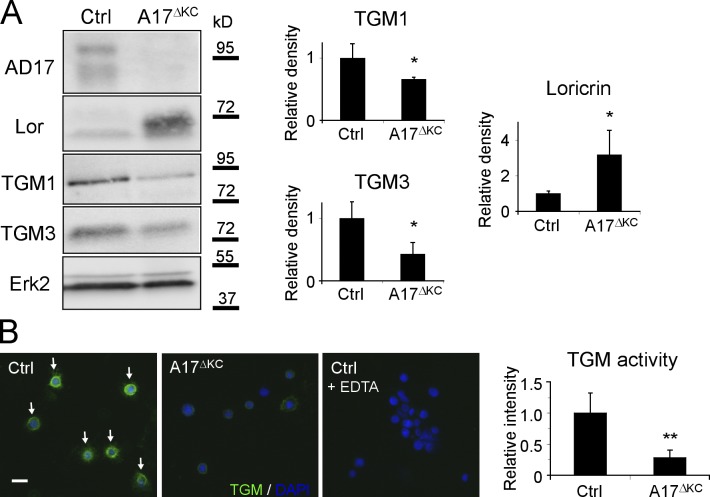

To elucidate whether the altered expression of terminal differentiation markers is cell autonomous, we analyzed their protein expression in a suspension culture of extracellular matrix (ECM)–disrupted primary A17ΔKC keratinocytes and controls (Wakita and Takigawa, 1999; Cheng et al., 2010). A17ΔKC keratinocytes showed significantly reduced levels of the TGMs 1 and 3 and concomitantly increased loricrin production (Fig. 3 A), suggesting cell-autonomous regulatory mechanisms. Furthermore, the TGM activity in A17ΔKC keratinocytes was strongly reduced in suspension cultures (Fig. 3 B).

Figure 3.

A17ΔKC keratinocytes exhibit cell autonomous dysregulated terminal differentiation. (A) Western blot of keratinocytes for expression of ADAM17 (AD17), TGMs 1 and 3, and loricrin (Lor) in A17ΔKC keratinocytes and controls (Ctrl). n = 3. (B) In vitro TGM activity in 24-h suspension-cultured control keratinocytes (arrows) and in A17ΔKC keratinocytes (n = 6). Wild-type keratinocytes probed with an excess of EDTA served as negative control. Bar, 20 µm. Results: mean ± SD, students t test: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Skin barrier defects in A17ΔKC animals induce IL-36α, immune cell influx, and hyperproliferative epidermis

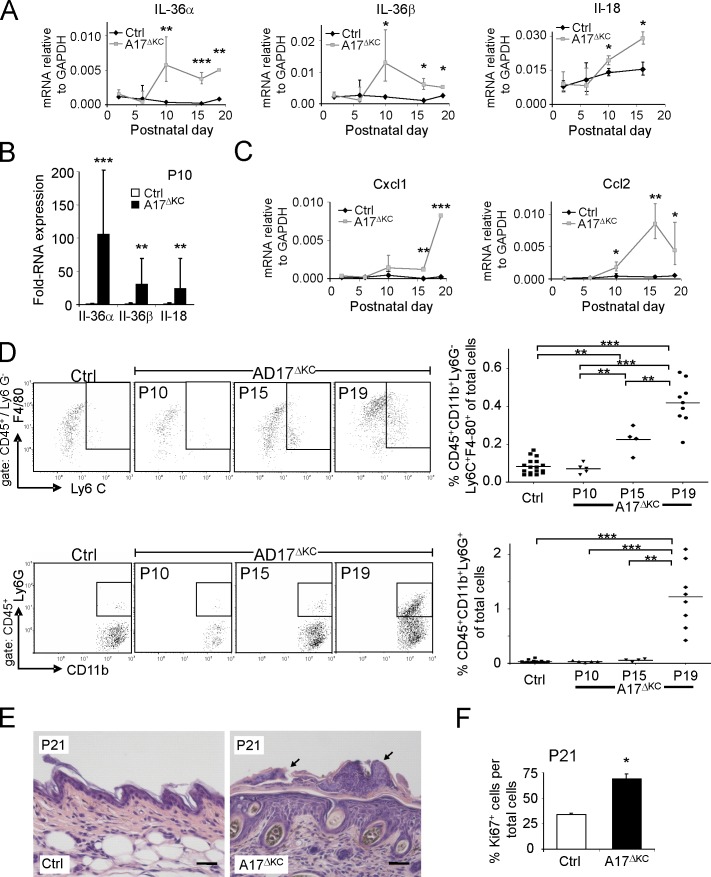

The microarray analysis on P10 skin identified the IL-1 family member IL-36α as the most prominent proinflammatory cytokine in A17ΔKC skin. A quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis for several IL-1 family members (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1ra, IL-36α, IL-36β, IL-36Ra, IL-18, and IL-18bp) showed no elevation at P2 and P6, in contrast to the significant increase of the keratinocyte-derived cytokines IL-36α, IL-36β, and IL-18 (Blumberg et al., 2007; Sims and Smith, 2010) at P10 (Fig. 4 A). qPCR from epidermis splits confirmed their epidermal origin (Fig. 4 B). Thus A17ΔKC keratinocytes begin to express proinflammatory cytokines at the onset of detectable epidermal barrier defects. In addition, the expression of the monocyte chemoattractant protein 1/CCL2 in the skin was significantly increased from P10, whereas the neutrophilic chemokine GRO-α/CXCL1 showed increased expression at P16 (Fig. 4 C).

Figure 4.

Skin barrier defects result in increased IL-36α, immune cell infiltration, and epidermal thickening. (A) qPCR analysis of P2-P19 skin for IL-36α, IL-36β, and IL-18. (B) qPCR analysis of P10 epidermis for IL-36α, IL-36β, and IL-18 (n = 4). (C) qPCR analysis of P2–P19 skin for CCL2, and CXCL1 relative to GAPDH. n ≥ 3. (D) Flow cytometry of skin cell suspensions gated for CD45+ and further analyzed for neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6G+) and inflammatory macrophages (CD11b+Ly6G−Ly6C+F4/80+). P10 (n = 5), P15 (n = 4), and P19 (n ≥ 8) are shown. (E) Sections of H&E-stained A17ΔKC skin at P21 showed neutrophil accumulation on the surface and adjacent to hair follicles (black arrows). (F) Percentage of Ki67-positive keratinocytes in A17ΔKC skin at P21 (n = 3). Bars, 50 µm. Results: mean ± SD. Student’s t test: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

To evaluate the potential consequences of increased cytokine and chemokine expression in the skin of A17ΔKC mice, we used histochemistry and flow cytometry of single-cell suspensions from skin to identify infiltrating immune cells. No infiltrating immune cells were detectable at P10, but a significant increase in inflammatory macrophages (defined as CD45+CD11b+Ly6G−Ly6C+F4/80+) was evident at P15 (Fig. 4 D, top). At P19, there was a strongly increased infiltration of neutrophils (identified as CD45+CD11b+Ly6G+) and inflammatory macrophages (Fig. 4 D) and significantly elevated numbers of mast cells (not depicted). In contrast, there was no detectable elevation of CD3+ T cell or CD19+ B cell populations (unpublished data). Histological analysis of trunk and ear skin of A17ΔKC mice at P21 showed significant neutrophilic infiltrates on the skin surface or close to the hair follicle canals (Fig. 4 E). The inflammatory responses in the skin most likely led to keratinocyte proliferation. At P10, when no immune cell infiltrates were detectable, the proliferating basal keratinocyte layer showed no changes (not depicted). At P21 there was significant epidermal hyperplasia with increased numbers of Ki67-positive cells (Fig. 4 F), coinciding with increased immune cell infiltrates.

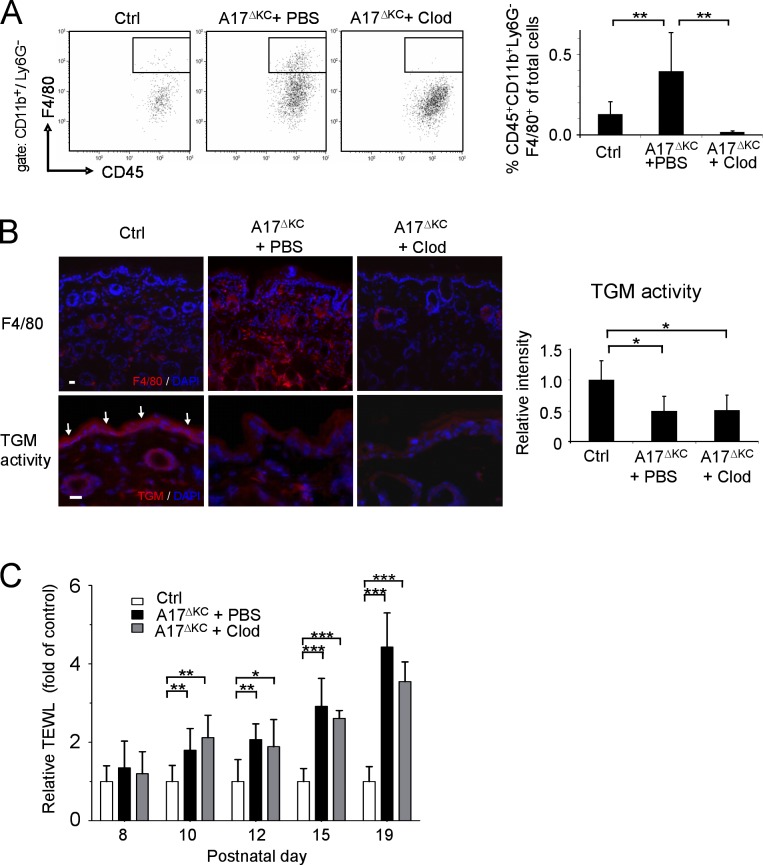

Inflammatory macrophages are not the primary cause of the skin barrier defect of A17ΔKC mice

The development of hyperproliferative skin diseases can potentially be triggered by skin macrophages (Stratis et al., 2006). However, the absence of inflammatory macrophages at P10 when epithelial barrier defects first became evident argued against such a mechanism in A17ΔKC mice. Yet because inflammatory macrophages were present at an early stage of barrier breakdown and preceded infiltration of neutrophils (Fig. 4 D), a significant contribution of macrophages as a primary cause of the epithelial barrier defects was still possible. To address this possibility, we depleted the macrophages in A17ΔKC skin by subcutaneous injection of clodronate-loaded liposomes starting at P8—before appearance of the first signs of the phenotype—until P19. This treatment dramatically reduced the number of macrophages in the dermis compared with PBS-liposome treated A17ΔKC littermates (Fig. 5, A and B, top) but did not improve epidermal TGM activity (Fig. 5 B, bottom) or the TEWL (Fig. 5 C).

Figure 5.

Infiltrating skin macrophages do not cause the skin barrier defects in A17ΔKC mice. For depletion of dermal macrophages, A17ΔKC mice were subcutaneously injected with clodronate-loaded liposomes (A17ΔKC + Clod) or PBS-loaded liposomes (A17ΔKC + PBS, Ctrl) into the back skin. (A) Flow cytometry of skin macrophages at P19 gated for CD11b+Ly6G− and further analyzed for skin macrophages (CD45+F4/80+; n = 5). (B) Immunofluorescence staining of A17ΔKC skin with anti-F4/80 antibodies to detect macrophages (top) and for TGM activity (bottom, arrows in Ctrl; n ≥ 5 per group). Bars, 20 µm. (C) TEWL from the back skin of A17ΔKC mice injected with clodronate-loaded (A17ΔKC + Clod) or control (A17ΔKC + PBS) liposomes and from control mice was detected from P8 to P19 (n ≥ 5 per group). Data are mean ± SD. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

EgfrΔKC mice have similar epidermal barrier defects and dysregulated keratinocyte differentiation to those of A17ΔKC mice

ADAM17 is the principal sheddase for several ligands of the EGFR (Peschon et al., 1998; Jackson et al., 2003; Blobel, 2005; Sternlicht et al., 2005). Western blot analysis of phosphorylated EGFR (pEGFR) revealed a pronounced reduction of pEGFR in A17ΔKC skin lysates with similar levels of total EGFR (Fig. 6 A). Egfr−/− mice have defects in hair and epithelial development (Miettinen et al., 1995; Sibilia and Wagner, 1995; Sibilia et al., 2003) resembling those in A17ΔKC mice; however, the effects of EGFR deficiency on epidermal barrier and CE formation have not been previously investigated.

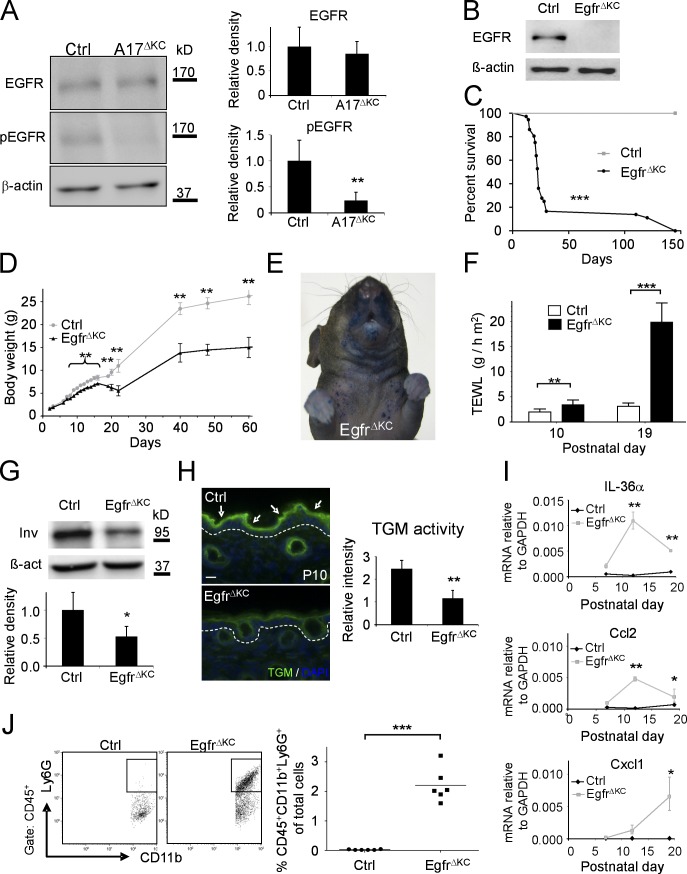

Figure 6.

EgfrΔKC mice have similar epidermal differentiation and barrier defects as A17ΔKC mice. (A) Western blot of A17ΔKC skin lysates for phospho-EGFR (pEGFR) and total EGFR compared with controls (Ctrl; n = 4). (B) Immunoblot analysis of epidermal splits of EgfrΔKC skin for EGFR. (C) Survival curve of control (Crtl) versus EgfrΔKC littermate mice (n = 30). Mantel-Cox test: ***, P < 0.001. (D) Body weight of EgfrΔKC versus control mice at different ages (n ≥ 4). (E) Pronounced toluidine blue dye penetration around the snout and the upper trunk of P15 EgfrΔKC animals (representative of three animals). (F) TEWL from EgfrΔKC mice compared with controls at P10 and P19 (n ≥ 4). (G) Western blot of P3 back skin with involucrin antibodies in EgfrΔKC versus control skin (Ctrl). n ≥ 3. (H) In situ TGM activity (arrows) in P10 skin from EgfrΔKC epidermis compared with controls (Ctrl; n = 3). The dashed line represents the basement membrane. Bar, 20 µm. (I) qPCR with total RNA from P7, P12, and P19 skin for IL36α, Ccl2, and Cxcl1. (J) Flow cytometry of P19 skin cell suspensions for neutrophilic infiltrates (CD45+CD11b+Ly6G+; n = 6). Results: mean ± SD. Student’s t test: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Previously described EgfrΔKC mice in a SV129/CL57BL6/FVB background were viable and fertile with wavy hair (Lee and Threadgill, 2009), although the severity of EGFR knockout mice phenotypes depends on the genetic background (Sibilia and Wagner, 1995; Threadgill et al., 1995). Therefore, we generated EgfrΔKC mice in the SV129/CL57BL6 background of the A17ΔKC mice. Lack of EGFR expression in epidermal splits was confirmed by immunoblot (Fig. 6 B). Furthermore, expression of ADAM17 in EgfrΔKC skin was comparable with littermate controls (unpublished data). EgfrΔKC mice developed very similar phenotypes to those of A17ΔKC mice, including curly whiskers and a 10% penetrance of open eyes at birth, delayed hair outgrowth, shortened and disorganized hair follicles at P10, and dry scaly skin on the face, scalp, ventral upper trunk, and tail at P19 (unpublished data). EgfrΔKC mice showed 85% lethality between P18 and P25, with survivors living up to 6 mo (Fig. 6 C) with pronounced growth retardation and ∼50% of maximal weight loss (Fig. 6 D). EgfrΔKC mice had significant dye penetration on the face, upper trunk, and paws at P15 (Fig. 6 E) and significant TEWL at P10, which was strongly elevated at P19 (Fig. 6 F). Similar to A17ΔKC mice, we found a significant reduction of the late terminal differentiation marker involucrin in the EgfrΔKC epidermis (Fig. 6 G) and increased keratin1 and loricrin mRNA expression (not depicted). Moreover, TGM activity was unchanged in the epidermis of EgfrΔKC mice at P2 (not depicted) but significantly reduced at P10 compared with controls (Fig. 6 H). Analysis of cytokine expression in the skin of EgfrΔKC mice showed no elevation of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1ra, and IL-36Ra, but significantly elevated IL-36α and Ccl2 at P12 (Fig. 6 I) and induction of Cxcl1, as well as strongly increased neutrophil and inflammatory macrophage infiltrates at P19 (Fig. 6, I and J; and not depicted). Thus the pathological changes in EgfrΔKC mice closely resembled those observed in A17ΔKC mice.

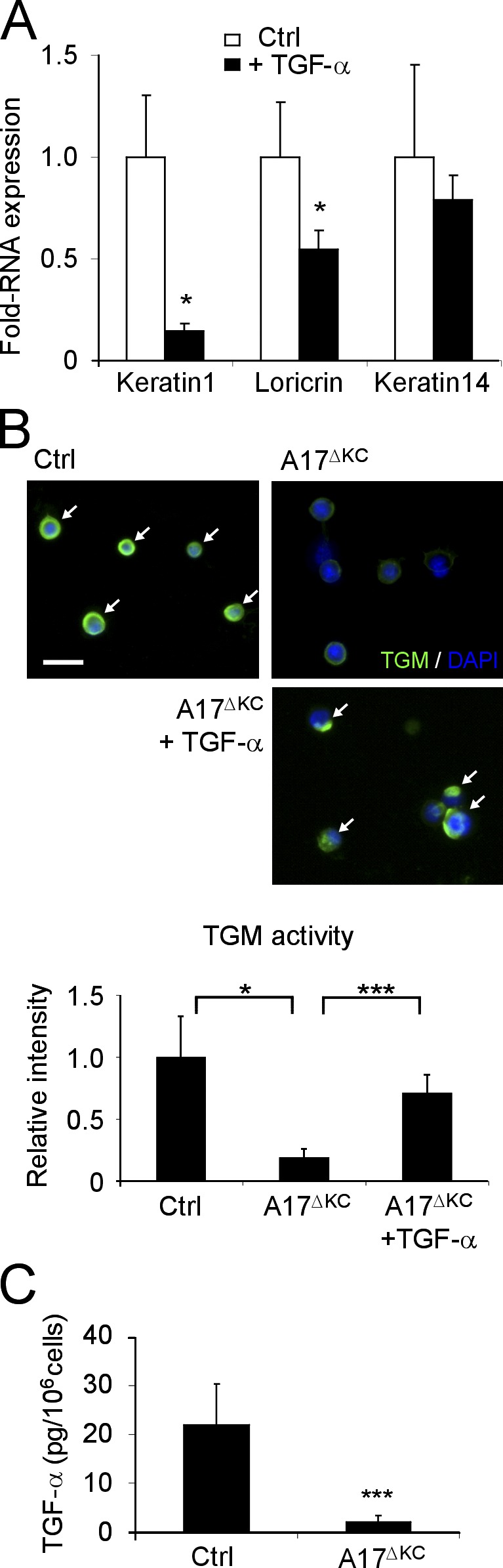

The EGFR ligand TGF-α regulates epidermal differentiation

Of the EGFR ligands whose shedding depends on ADAM17 (Sahin et al., 2004), TGF-α is mainly responsible for epidermal development and hair growth (Luetteke et al., 1993; Mann et al., 1993; Schneider et al., 2008). Quantitative analysis of RNA expression level of EGFR ligands in wild-type P2 skin revealed the highest levels for TGF-α, with fivefold more expression than HB-EGF and ∼2.5-fold more expression than amphiregulin or epiregulin (unpublished data).

We therefore sought to determine whether TGF-α is involved in the differentiation of primary keratinocyte cultures. When we used a Ca2+-induced keratinocyte differentiation assay (Pillai and Bikle, 1991), we found that Ca2+ treatment increased the release of TGF-α from keratinocytes by ∼50% compared with untreated controls (Dlugosz et al., 1994; not depicted). When suspension cultures of keratinocytes (Wakita and Takigawa, 1999; Cheng et al., 2010) were treated with 30 ng/ml TGF-α for 48 h, we found significantly reduced keratin 1 and loricrin mRNA expression, whereas keratin 14 expression remained unchanged (Fig. 7 A). Thus, stimulation of the EGFR by TGF-α had the opposite effect on the keratinocyte differentiation markers keratin1 and loricrin as deletion of ADAM17 (Fig. 2 A). Importantly, the reduced TGM activity in ECM-disrupted A17ΔKC keratinocytes was nearly completely restored by recombinant TGF-α (Fig. 7 B), suggesting that the lack of EGFR activation is the major cause of the loss of TGM activity in ADAM17-deficient keratinocytes.

Figure 7.

EGFR stimulation with TGF-α regulates terminal differentiation. (A) ECM-disrupted keratinocyte suspensions were incubated with and without 40 ng/ml TGF-α for 48 h, and total RNA was then analyzed by qPCR for keratin1, loricrin, and keratin14 (n = 3). (B) Suspension cultured keratinocytes analyzed for in vitro TGM activity (arrows). Bar, 20 µm. A17ΔKC keratinocytes were cultured with 40 ng/ml TGF-α when indicated (n = 3 per group). (C) TGF-α ELISA in the supernatants of control and A17ΔKC keratinocytes cultured for 24 h (n = 7). Results: mean ± SD. Student’s t test: *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001.

To address the role of ADAM17/TGF-α in epidermal barrier maintenance in vivo, we first determined whether TGF-α levels are altered in A17ΔKC skin. No differences in the RNA expression or protein staining were observed in the A17ΔKC animals compared with controls (unpublished data). In addition, no significant differences in the expression of HB-EGF, amphiregulin, and epiregulin mRNA were found in A17ΔKC mice versus controls (unpublished data). However, shedding of TGF-α from primary A17ΔKC keratinocytes was strongly reduced compared with controls (Fig. 7 C).

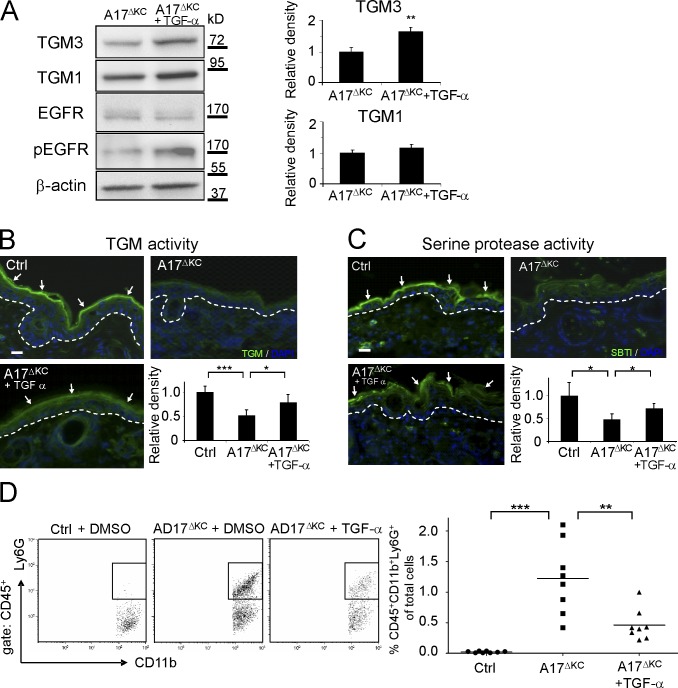

To determine whether the lack of TGF-α shedding from the epidermis was responsible for the skin barrier breakdown and subsequent skin inflammation, we applied recombinant TGF-α or DMSO as control daily to a defined area of A17ΔKC skin from P8 to P19 and measured EGFR phosphorylation, TGM activity, compensatory serine protease activity, and immune cell infiltrates. Western blot analysis revealed a pronounced increase of phospho-EGFR and TGM3 in TGF-α–treated A17ΔKC skin (Fig. 8 A). Moreover, TGF-α significantly improved TGM activity in A17ΔKC skin at P19 (Fig. 8 B) with ∼65% increased TGM3 expression. TGF-α also reversed the compensatory reduction of serine protease activity in the stratum corneum of P19 mutant skin (Fig. 8 C) and reduced infiltrating neutrophils by 60% (Fig. 8 D) and inflammatory macrophages by 40% (not depicted). Furthermore, the daily application of recombinant TGF-α to a defined area of EgfrΔKC skin from P8 to P19 did not affect the infiltration of immune cells or TGM activity (unpublished data).

Figure 8.

Application of TGF-α reconstitutes the skin barrier. (A) Immunoblot analysis of DMSO control versus TGF-α–treated A17ΔKC skin (n = 4). (B) TGM activity (arrows) in P19 control or A17ΔKC skin treated with TGF-α (n = 5 per group). (C) Serine protease activity (detected with SBTI Alexa Fluor 488 conjugates; arrows) in control or A17ΔKC skin treated with TGF-α (n = 3). The dashed lines in B and C represent the basement membrane. (D) For flow cytometric detection, the skin cell suspensions were gated for CD45 and further analyzed for neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6G+; n = 8 per group). Results: mean ± SD. Student’s t test: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Bars, 20 µm.

Chronic deficiency of keratinocyte-derived ADAM17 results in atopic dermatitis-like disease

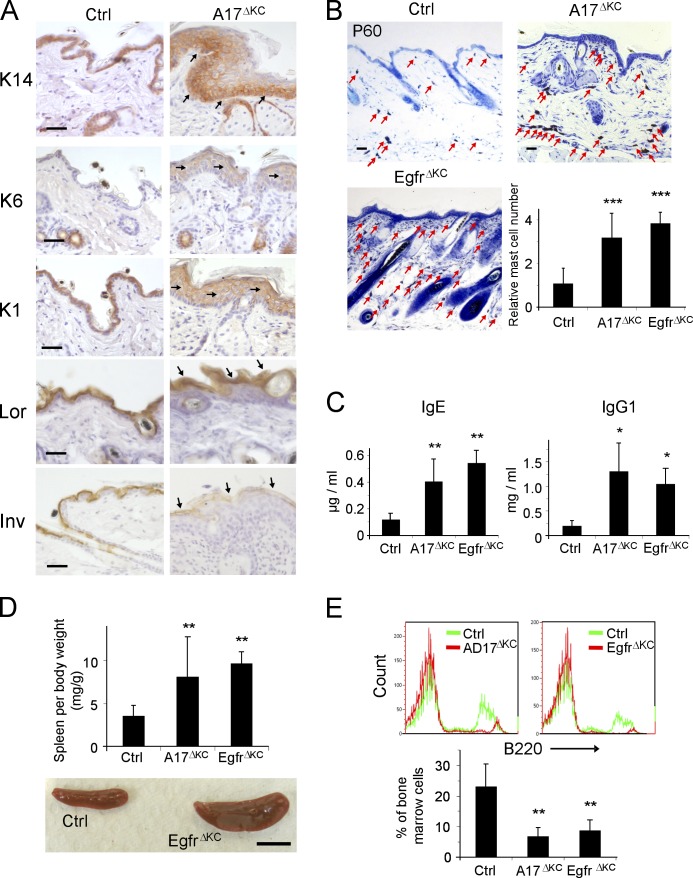

20% of the A17ΔKC mice survived up to 6 mo, thus allowing us to examine the chronic effects of keratinocyte-ADAM17 deficiency. Older A17ΔKC mice displayed all characteristic manifestations of a defective epidermal barrier and dehydration, including dry scaly skin, significantly increased serum sodium, reduced skin turgor, and 50% weight loss (unpublished data). Furthermore, compared with control littermates, they exhibited strong scratching as a sign of intense pruritus, which is characteristic of chronic dermatitis with epidermal barrier defects (Habif, 2009). Histological analysis confirmed altered epidermal differentiation, with increased expression of keratin 1 and loricrin and lower expression of involucrin, one of the initiator proteins in the cornification, suggesting dysregulated terminal differentiation (Fig. 9 A). Long-term surviving A17ΔKC mice also demonstrated pronounced epidermal hyperproliferation, similar to A17ΔKC animals at P21 (Fig. 4 F), with increased cell numbers, keratin14, keratin1, and epidermal staining of the hyperproliferation marker keratin 6, which is normally only produced in the midportion of the hair follicles of control skin (Fig. 9 A). In addition, toluidine blue staining and flow cytometry of back skin of 60-d-old mice revealed pronounced dermal accumulation of mast cells (Fig. 9 B), and strongly elevated numbers of inflammatory macrophages (CD45+CD11b+Ly6G-F4/80+) and T cell populations (CD3+; not depicted). The epidermal thickening was most likely induced by the severe infiltration of inflammatory cells. The prolonged skin inflammation of the A17ΔKC mice presumably also caused systemic defects with significantly increased serum concentrations of IgE und IgG1 (Fig. 9 C), splenomegaly (Fig. 9 D) and enlarged lymph nodes (not depicted), and severely decreased bone marrow B220+ populations (Fig. 9 E) in P60 A17ΔKC mice compared with controls. Similar pathological changes were observed in the skin of P60 EgfrΔKC mice (Fig. 9 B-E), suggesting that impaired EGFR signaling causes these defects in A17ΔKC mice.

Figure 9.

Prolonged epidermal ADAM17 deficiency leads to chronic dermatitis. (A) Immunohistological staining of P60 epidermis with antibodies against the basal keratinocyte marker keratin14, hyperproliferation marker keratin 6, the early differentiation marker keratin1, and the terminal differentiation markers involucrin and loricrin. Arrows indicate staining localization. (B) Toluidine blue staining of back skin sections revealed a pronounced dermal accumulation of mast cells (arrows; n = 4). Bars: (A and B) 50 µm. (C) Concentrations of IgE and IgG1, measured by ELISA in serum of P60 animals (n ≥ 3). (D) Spleen weight in control, A17ΔKC, and EgfrΔKC animals (n = 14). Bar, 1 cm. (E) Anti-B220 PE-stained B cell populations compared with controls in bone marrow flow cytometry (n ≥ 4). Data are mean ± SD. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

The skin provides an important protective physical barrier, yet the molecular mechanisms responsible for maintaining this barrier remain poorly understood. Here we report that the ADAM17–EGFR signaling axis in keratinocytes regulates the integrity of the skin barrier by promoting terminal keratinocyte differentiation and the cross-linking activity of TGMs. Lack of ADAM17 in keratinocytes led to severe epidermal barrier defects, resulting in TEWL, inflammatory infiltrates, and increased mortality. ADAM17 regulates the skin barrier by controlling EGFR ligand shedding and EGFR signaling in keratinocytes, as indicated by lack of TGF-α shedding from A17ΔKC keratinocytes and the similar phenotype of EgfrΔKC and A17ΔKC mice. Notably, application of TGF-α to A17ΔKC skin restored epidermal barrier integrity by stimulating skin TGM activity and thereby reducing immune infiltrates. Our findings highlight the essential role of the ADAM17–TGF-α (or other EGFR ligands)–EGFR signaling pathway in maintaining epidermal barrier homeostasis.

The integrity of the epidermal barrier depends on the continuous regeneration of the cornified layer. Cornification is a tightly controlled process, which requires coordinated keratinocyte proliferation, detachment, migration and cell death by terminal differentiation. A striking finding in the epidermis of the A17ΔKC animals was the defect in terminal keratinocyte differentiation and cornified layer formation, which was very similar to that observed in EgfrΔKC mice. The release of the ADAM17 substrate and EGFR ligand TGF-α was increased in differentiating wild-type keratinocytes, and TGF-α stimulated the differentiation of suprabasal-like keratinocytes, as indicated by reduced keratin 1 and loricrin and increased TGM expression (Dlugosz et al., 1994; Peus et al., 1997; Wakita and Takigawa, 1999; Cheng et al., 2010). Accordingly, A17ΔKC keratinocytes had increased loricrin levels and decreased TGM expression. These findings implicate ADAM17 in cell-autonomous regulation of keratinocyte differentiation and regeneration of the cornified layer through shedding of TGF-α.

Previous studies revealed immature or absent keratinization of the stratum corneum in newborn Egfr−/− mice (Miettinen et al., 1995; Sibilia and Wagner, 1995). In contrast, in our study both A17ΔKC and EgfrΔKC animals were born with normal epidermal barrier integrity. The severe inside-out barrier defects with significant TEWL and the outside-in barrier defects only became evident around postnatal day 10. The more severe phenotype of Egfr−/− and Adam17−/− knockout mice is most likely explained by the compounded effects of EGFR or ADAM17 deficiency in all tissues. Our findings suggest that ADAM17/EGFR signaling in keratinocytes only plays a minor role in the development of an intact skin barrier in utero and in newborn mice but that it is crucial for the renewal of the CE in postnatal development and adults. Consistent with our findings of a normal epidermal barrier in newborn A17ΔKC and EgfrΔKC mice, the TGM activity, necessary for cross-linking of proteins and formation of the CE, was normal at birth but significantly decreased at P10. Interestingly, control littermates had strongly elevated expression of TGM1 and TGM3 (unpublished data) and increased TGM activity at P10 compared with P2, suggesting an increased importance of TGMs in forming and maintaining the CE as the animals grow older. Consistent with this, about a threefold increase in TGM activity was detected in adult murine skin compared with P2 skin (Kagehara et al., 1994). The reduction of both TGM transcripts in A17ΔKC skin at P10 and in ADAM17 deficient keratinocytes indicate that both TGMs are regulated cell autonomously by EGFR signaling, as further corroborated by enhanced TGM expression and activity after treatment with TGF-α. Interestingly, the severity of autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis, a disorder of keratinization caused by mutations in TGM1, correlated with the decrease in skin TGM activity (Akiyama et al., 2003).

The reduced TGM activity in A17ΔKC epidermis resulted in the production of an immature CE and denser stratum corneum with significantly increased numbers of corneocytes. The strongly reduced serine protease activity in the cornified layer is likely a consequence of the decreased TGM activity because serine protease and TGM activity were normal in P2 A17ΔKC skin. Previous studies have shown that a reduced integrity of the cornified layer can be associated with a compensatory decrease in desquamation, resulting in a thickened stratum corneum that maintains skin barrier function. This effect has been documented in Tgm1−/− skin grafts on nude mice, which formed a hyperkeratotic stratum corneum with significantly reduced TEWL (Kuramoto et al., 2002). Desquamation is an active process, which depends on a well balanced degradation of the corneodesmosomal adhesion molecules by the serine proteases kallikrein 7 and 5, which in turn are activated by other kallikreins (Eissa and Diamandis, 2008). Thus the decreased serine protease activity in the A17ΔKC skin is most likely responsible for the reduced desquamation. Interestingly, kallikreins were not down-regulated in microarrays of A17ΔKC skin (unpublished data) but instead serpina3 members were up-regulated, which can irreversibly inhibit several kallikreins and thereby regulate corneocyte detachment (Caubet et al., 2004; Ny and Egelrud, 2004; Baker et al., 2007).

The expression of proinflammatory cytokines in keratinocytes was most likely triggered by epidermal barrier defects because it increased at the same time that significant TEWL on the skin surface first became apparent and coincided with reduced TGM activity in A17ΔKC skin. Previous studies have shown that acute skin barrier defects led to epithelial cytokine production, especially of IL-1 family members (Wood et al., 1992; Ye et al., 2002; Yang et al., 2010). We found that skin barrier defects in A17ΔKC preferentially up-regulated the expression of the novel IL-1 family member IL-36α (Sims and Smith, 2010) and, to a lesser degree, IL-36β and IL-18. We detected similar IL-1 family member expression patterns in the skin of EgfrΔKC animals. The proinflammatory effects of IL-36α have been demonstrated in vivo by transgenic overexpression of IL-36α in the epidermis (Blumberg et al., 2007) and by the development of generalized pustular psoriasis in patients with an inactivating mutation in the IL-36 receptor antagonist (IL-36Ra), a protein which normally blocks activation of the IL-36 receptor (also referred to as IL-1 receptor-related protein type 2; IL-1Rrp2) by IL36α, β, and γ (Marrakchi et al., 2011). Interestingly, pronounced epidermal expression of IL-36β was previously reported in epidermis-specific FGFR1/FGFR2 double knockout mice, which develop progressive skin barrier defects associated with immune cell infiltrates, comparable with the A17ΔKC mice (Yang et al., 2010). Recent studies have shown that the FGFR2 activates the EGFR and ERK1/2 by stimulating ADAM17 and release of EGFR ligands, providing a possible explanation for the similar phenotypes of FGFR1/FGFR2 double knockout mice and A17ΔKC mice (Maretzky et al., 2011). Thus, our findings support a model in which EGFR signaling in the epidermis has immunoregulatory functions by maintaining terminal keratinocyte differentiation.

Over time, the surviving A17ΔKC mice developed a chronically thickened epidermis, dry skin, severe inflammatory dermal infiltrates, and systemic myeloproliferative disease. Murthy et al. (2012) recently described a similar inflammatory skin phenotype in A17ΔKC mice but proposed that it is caused by the loss of a putative ligand-independent Notch activation by ADAM17, which, in turn, would normally suppress the production of thymic stromal lymphoprotein (TSLP) in adult skin. However, another study has shown that TSLP is produced as a consequence of skin barrier defects in general and does not depend on loss of Notch signaling (Demehri et al., 2008). Importantly, we demonstrate that the invasion of inflammatory cells is a consequence of the skin barrier defects, and not the cause, because skin defects develop in A17ΔKC mice before inflammatory infiltrates and are not reversed by macrophage depletion with clodronate. Moreover, our study identifies EGFR-dependent regulation of TGMs, which are directly responsible for establishing the skin barrier, as the most likely basis of the skin defect in A17ΔKC mice. This mechanism is further supported by the finding that EgfrΔKC mice develop chronic dermatitis and systemic myeloproliferative disease, just like A17ΔKC mice, and by rescue experiments of A17ΔKC mice with the EGFR ligand and ADAM17 substrate TGF-α. Therefore, we conclude that chronic dermatitis and systemic myeloproliferation in ADAM17 knockout mice are late manifestations of persistent EGFR ligand deficiency and the resulting defective skin barrier. In this context, it should also be noted that previous studies have demonstrated both agonistic and antagonistic cross talk between the EGFR and Notch pathways (Yoo et al., 2004; Hasson et al., 2005; Doroquez and Rebay, 2006; Aguirre et al., 2010), suggesting that the reduced Notch signaling observed by Murthy et al. (2012) in A17ΔKC skin could also be explained by lack of EGFR activation. Finally, both A17ΔKC and EgfrΔKC mice showed an outside-in barrier defect, which is thought to contribute to the pathogenetic mechanism of atopic dermatitis by exposing the skin to exogenous agents or antigens, which then trigger immune reactions (Irvine and McLean, 2006; Moniaga et al., 2010).

Of the EGFR ligands that are shed by ADAM17 (Sahin et al., 2004), TGF-α is the principal growth factor required for epidermal differentiation and hair growth in mice (Luetteke et al., 1993; Mann et al., 1993) and it is the most highly expressed EGFR ligand in skin. However, other EGFR ligands also regulate important keratinocyte functions, such as keratinocyte migration, which is stimulated by heparin binding EGF (HB-EGF) and increased keratinocyte proliferation in psoriasis-like cutaneous pathologies by amphiregulin (Schneider et al., 2008; Maretzky et al., 2011). It is therefore possible that several ADAM17-dependent EGFR ligands coordinately support epidermal barrier development and maintenance.

The EGFR signaling pathway is an established target for treatment of various cancers (Hynes and Lane, 2005). Interestingly, dermatologic side effects frequently appear during the first 3 wk of treatment, especially on skin regions with high density of sebaceous glands, like the scalp, face, and upper chest. These side effects include inflammatory papulopustular acneiform rash, hair changes, itching (pruritus), and skin dryness (xerosis), whereas the mostly sterile inflammatory rash accompanied with itchy xerotic skin is the most frequent manifestation (Pastore and Mascia, 2008; Lacouture et al., 2011). Recently, similar anti-EGFR antibody-induced neutrophil-rich skin inflammation combined with epithelial thickening of the face und upper trunk has been reported in immunodeficient (SCID) mice after the 3rd wk of treatment (Surguladze et al., 2009). Although the clinical manifestations are well characterized, the direct mechanistic cause of these inflammatory skin reactions is still unclear (Lacouture, 2006). Because depletion of ADAM17 or the EGFR in the epidermis lead to xerotic inflammatory skin, preferentially at sites with high density of sebaceous glands, it is likely that the gene-targeted mice and patients share the same mechanistic cause of epidermal pathology. This notion is further supported by a recent report of the first inactivating mutation in the ADAM17 gene borne by a human patient, who has developed an inflammatory skin and bowel disease with neonatal onset, strongly elevated T cell skin infiltrates, and reduced TGM1 expression in the skin (Blaydon et al., 2011). Thus, the insights gained from A17ΔKC mice have significant translational relevance. Understanding the biological consequences of the blockage of ADAM17-dependent EGFR signaling in the skin could lead to the development of better therapeutic strategies for the dermatologic side effects of EGFR antagonists in cancer patients and the treatment of patients carrying mutant alleles of ADAM17.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

The generation of Adam17flox/flox and EGFRflox/flox mice has been described previously (Horiuchi et al., 2007; Lee and Threadgill, 2009). Both strains were crossed with keratin-14-Cre (Krt14-Cre) transgenic mice (004782, STOCK Tg(KRT14-cre)1Amc/J; The Jackson Laboratory). Adam17flox/+Krt14-Cre mice were crossed with Adam17flox/flox mice to generate Adam17flox/flox Krt14-Cre mice, referred to as A17ΔKC. An essentially identical approach yielded Egfrflox/flox Krt14-Cre mice, referred to as EgfrΔKC. In both cases, the genotypes of the offspring followed a Mendelian distribution. Transgenic ROSA26-LacZ reporter mice were from The Jackson Laboratory (003309, B6.129S4-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1Sor/J). All mice were of mixed genetic background (129Sv, C57BL/6), and all comparisons were between littermates. Serum sodium concentrations were measured on a Chemistry Analyzer (AU400; Beckman Coulter). In some experiments, mice received daily applications of TGF-α (1.5 µg/mouse) or vehicle (80% DMSO in PBS) on their ventral neck and one ear. For depletion of skin macrophages, we subcutaneously injected 100 µl of Clodronate-loaded liposomes or PBS-loaded liposomes as control every other day into the back skin of A17ΔKC or EgfrΔKC mice and their control littermates starting at P8 until P18. Clodronate- or PBS-loaded liposomes were prepared as described previously (van Rooijen and van Kesteren-Hendrikx, 2003). The mice were maintained in the Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) Animal Facility and at the Biomedical Research Centre of the University Medical Center in Freiburg, and all experiments were performed according to the guidelines of the American Veterinary Association and the German Animal Welfare association and approved by the HSS Internal Animal Care and Use Committee or the Regierungspräsidium Freiburg.

Tissue histology of the Krt14-Cre/ROSA26Lac-Z reporter mice.

The tissue expression pattern of the keratin 14 promoter was analyzed using offspring of matings of Adam17wt/floxKrt14-Cre mice with Adam17flox/flox ROSA26-lac-Z mice (R26R), which express β-galactosidase upon Cre-mediated excision of a loxP-flanked STOP codon. The tissues taken from P14 or P28 animals were fixed with 4% PFA in PBS for 2 h and incubated with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-d-galactosidase staining solution at 37°C overnight, and subsequently embedded in paraffin. The tissue sections were counterstained with eosin.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis.

Total RNA from mouse skin, epidermal splits, or primary keratinocyte cultures was extracted using RNeasy (QIAGEN). 1 µg of total RNA was reverse transcribed using a First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Fermentas). Relative quantification of gene expression was performed by real-time qPCR using iQ SYBR-green Supermix on a Thermal Cycler (CFX96 C1000; Bio-Rad Laboratories) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. All primer sequences are shown in Table S1. Relative expression was normalized for levels of GAPDH. The generation of the correct amplification products was confirmed using agarose gel electrophoresis.

Primary keratinocyte preparation and cultivation.

Keratinocytes were isolated from the skin of A17ΔKC or EgfrΔKC mice and their wild-type littermates essentially as described (Franzke et al., 2009). In brief, the skin was washed with PBS containing 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (Invitrogen, Germany), and epidermis and dermis were detached by overnight digestion with dispase (STEMCELL Technologies) at 4°C. The epidermis was incubated with 0.25% trypsin (wt/vol) and 2 mM EDTA for 30 min at 37°C under vigorous shaking. After stopping the reaction with PBS containing 10% FCS, the keratinocyte suspension was passed through a 45-µm sieve, and 105 cells/cm2 were plated in defined serum-free keratinocyte medium (CellnTec) supplemented 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen). The cells were maintained in defined serum-free keratinocyte medium at 37°C in 5% CO2, and medium was replaced every 48 h. Subconfluent cells derived from passages 1–3 were used for the experiments.

Keratinocyte cell suspension cultures.

Suspension culture on polyhydroxyethyl-methacrylate (poly-HEMA)–coated plates was performed as previously described (Wakita and Takigawa, 1999). 6-well plates were coated with poly-HEMA (Sigma-Aldrich), followed by extensive PBS washes. 2 ml of cell suspension was added in each coated well and incubated in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 in air at 37°C for 24 or 48 h. After centrifugation the cell pellets were either used for the preparation of cell lysates or total RNA extraction or for the in vitro detection of TGM activity. For the detection of TGM activity, we attached 24-h suspension-cultured keratinocytes on gelatin-coated coverslips and preincubated them with 1% BSA in 0.1M Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, for 30 min at room temperature. Afterward, we detected the TGM activity as described in the Enzyme activity assays section.

Histology.

Tissues were fixed in 3.7% buffered formaldehyde or 4% PFA and embedded in paraffin. 5-µm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and toluidine blue.

Immunohistochemistry.

Paraffin sections or cryosections of 5 µm were stained using mAb against Ki67 (1:50; clone TEC-3; Dako), keratin 14 (1:200; clone LL001; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), and polyclonal rabbit antibodies against human TGF-α (1:50; R&D systems), keratin1 (1:1,000; Abcam), loricrin (1:1,000; GeneTex), keratin 6, involucrin (1:500; Covance), and TGM1 and TGM3 (both 1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). For visualization, the sections were incubated with either biotinylated secondary anti–mouse IgG or anti–rabbit IgG antibodies (Dako) using the VECTASTAIN ABC kit and Nova RED substrate kit (Vector Laboratories) or with Alexa Fluor 488– or Alexa Fluor 594–conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen), followed by embedding with mounting medium supplemented with DAPI (Vector Laboratories). Epidermal lipids in skin cryosections were visualized using 2.5 µg/ml Nile red for 2 min at RT. Specimens were viewed with a brightfield and epifluorescence microscope (Axio Imager A1 equipped with AxioCam MRm and MRc cameras; Carl Zeiss) using AxioVision software (version 4.8.2; Carl Zeiss) and processed using ImageJ software (version 1.43u; National Institutes of Health).

Immunoblotting.

For Western blot analysis, the samples were processed as previously described (Franzke et al., 2009). The cells and tissues were lysed in 25 mM Tris-HCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, and 0.1 M NaCl, pH 7.4, supplemented with 2 mM EDTA, 5 mM 1,10-ortho-phenanthroline (Sigma-Aldrich), and protease inhibitor cocktail set III (EMD). Epidermal sheets were detached from the dermis by digestion with dispase (STEMCELL Technologies) at 37°C. Tissues were homogenized in lysis buffer on ice with a T18 basic Ultra Turrax (Ika). Total protein content was determined using the BCA protein assay kit (Invitrogen) and 25 µg total protein per sample was separated by electrophoresis on 7 or 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Immunoblots were probed with anti-keratin 14 mAb (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), anti-EGFR rabbit pAbs (Cell Signaling Technology) or anti–phospho-EGFR (pY1068, clone EP774Y; Epitomics Inc.), polyclonal rabbit antibodies against the cytoplasmic domain of ADAM17 (Schlöndorff et al., 2000), TGM1, TGM3, and Erk1/2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Thr202/Tyr204; Cell Signaling Technology Inc.), keratin1 (Abcam), loricrin (GeneTex, USA) and involucrin (Covance), and secondary HRP-coupled anti–mouse and anti–rabbit IgG antibodies. Immunoblot signals were quantified with Fusion SL and BIO-1D Advanced software (PeqLab Biotechnologie GmbH).

Enzyme activity assays.

For in situ detection of TGM activity in skin sections, we used the biotinylated amine donor substrate monodansylcadaverine (biotMDC) as described earlier (Raghunath et al., 1998). Cryostat sections were air dried and preincubated with 1% BSA in 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.4 or pH 8.4, for 30 min at room temperature. The sections were then incubated for 2 h with 100 µM biotMDC, 5 mM CaCl2, 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.4 (for TGM1) or pH 8.4 (for TGM1 and TGM3). After stopping the reaction with 10 mM EDTA and extensive PBS washing, the sections were stained with Streptavidin-conjugated Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) and DAPI-supplemented mounting medium. For in situ detection of serine protease activity in cryostat sections of skin, we incubated 0.5 µg/ml of the SBTI Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate in 1% BSA in 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, for 20 min at room temperature. Negative controls were incubated with excess concentrations of uncoupled SBTI. After extensive washing, the sections were processed with DAPI supplemented mounting medium.

ELISA.

TGF-α released from confluent keratinocytes in a 3.5-cm cell culture plate for 24 h was measured with an ELISA kit for human TGF-α (RayBiotech, Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The supernatants were concentrated by 70% ethanol precipitation. Ig isotype sandwich ELISAs were performed by standard procedures. 96-well microtiter plates (NUNC) were coated with rat anti–mouse IgG1 (Invitrogen), IgG2a, IgM (BD), and sheep anti–mouse IgE (The Binding Site Group, Ltd.) and detection by HRP-coupled anti–mouse IgG1, IgG2a, IgM, and biotinylated anti–mouse IgE (all BD). Standard immunoglobulins were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Preparation of CEs.

A defined area of dorsal mouse skin (25 mm2) was boiled in isolation buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 10 mM DTT, and 2% SDS) under vigorous shaking for 40 min. After centrifugation, the CEs were washed twice with isolation buffer and were analyzed using a hemocytometer (Aho et al., 2004).

Detection of TEWL and dye exclusion assay.

The TEWL on shaved back skin was measured with a Tewameter (TM-300; Courage and Khazaka). For toluidine blue staining, newborn to P15 mice were sacrificed and dehydrated by sequential incubation in 25, 50, 75, and 100% methanol. After rehydration in PBS, they were incubated for 10 min in 0.01% toluidine blue and destained with PBS.

Flow cytometry.

Bone marrow cells were flushed from femurs and tibias with PBS using a 27G needle and passed through a 70-µm sieve. Skin cell suspensions were obtained from defined areas of ventral neck skin and one ear (400 mm2). Skin was minced and incubated in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution buffer containing 2.4 U liberase DH and 100 µg/ml DNase I (Roche) for 2 h under vigorous shaking and the cell suspension was passed through a 45-µm sieve, and the cells were stained with the following antibody conjugates: biotinylated anti-CD45, anti-CD115 PE, anti-CD11b PE-Cy7 (eBioscience), anti-CD3 FITC, anti-B220 PE, anti-CD19 PE, anti-CD117 PECy7, anti-FcεRIα PE, anti-Ly6G FITC, anti-Ly6C PerCP-Cy5.5 (BD), and anti-F4/80 APC (Serotec). Biotin-conjugated Abs were revealed with Streptavidin eFluor 450 (eBioscience). Data were acquired and analyzed on a Beckman Coulter Gallios instrument using Kaluza software (Beckman Coulter).

Microarray processing and data analysis.

Total RNA from P10 full back skin of either two A17ΔKC or two wild-type littermate mice was prepared using the RNeasy Fibrous Tissue Mini kit (QIAGEN). After determination of the RNA concentration (NanoDrop ND-1000; Wilmington) and of RNA quality with a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies), the samples were further processed for transcriptome analyses with the Agilent 4 × 44K whole mouse genome oligo expression microarray kit (Design ID 014868) according to the Agilent One-Color Microarray-Based Gene Expression Analysis protocol. The raw data were analyzed using GeneSpring GX 10.0 (normalization: shift to 75th percentile, baseline transformation: median of all samples). The normalized data were filtered to exclude probes flagged absent in all samples. The remaining probes were tested for statistical significance of expression using a two-sample Student’s t test (unpaired) with asymptotic p-value computation and a cut off of 0.05. Multiple testing correction was performed according to Benjamini-Hochberg (Klipper-Aurbach et al., 1995; P ≤ 0.05). The cutoff for the fold change is ≤2 (1 log2) up- or down-regulation.

Statistics.

All parametric data are present as mean ± SD. Data of two groups were analyzed for significance using the Student’s t test and the statistical analysis of survival curves was performed using the Mantel-Cox test. Both calculations were performed with Prism version 5.0 (GraphPad Software). For all analyses, n = number of experiments, and differences are considered to be statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Online supplemental material.

Table S1 lists the primer sequences used for quantitative RT-PCR analysis. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20112258/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Elin Mogollon and Björn Wienke for excellent technical assistance, Elvira Brucker for determining serum sodium levels, Britta Dorn for Ig isotype analysis, and Dr. Kristina Beck for advice on B-cell FACS analysis. Clodronate (Cl2MDP) was a gift from Roche.

This work was supported by the Research Commission of the Medical Faculty, University of Freiburg (FRA725/09) to C.-W. Franzke, the German Research Foundation DFG (SFB 850/B6) to L. Bruckner-Tuderman and C.-W. Franzke, the Excellence Initiative of the German federal and state governments, the Freiburg Institute for Advanced Studies, School of Life Sciences – LifeNet to L. Bruckner-Tuderman, the European Union (FP7-IRG268390) to A. Triantafyllopoulou, NIH-R01 CA092479 to D.W. Threadgill, and GM64750 to C.P. Blobel.

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- CE

- cornified envelope

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- EGFR

- epidermal growth factor receptor

- SBTI

- soybean trypsin inhibitor

- TEWL

- transepidermal water loss

- TGM

- transglutaminase

References

- Aguirre A., Rubio M.E., Gallo V. 2010. Notch and EGFR pathway interaction regulates neural stem cell number and self-renewal. Nature. 467:323–327 10.1038/nature09347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aho S., Li K., Ryoo Y., McGee C., Ishida-Yamamoto A., Uitto J., Klement J.F. 2004. Periplakin gene targeting reveals a constituent of the cornified cell envelope dispensable for normal mouse development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:6410–6418 10.1128/MCB.24.14.6410-6418.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama M., Sawamura D., Shimizu H. 2003. The clinical spectrum of nonbullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma and lamellar ichthyosis. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 28:235–240 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01295.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker C., Belbin O., Kalsheker N., Morgan K. 2007. SERPINA3 (aka alpha-1-antichymotrypsin). Front. Biosci. 12:2821–2835 10.2741/2275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black R.A., Rauch C.T., Kozlosky C.J., Peschon J.J., Slack J.L., Wolfson M.F., Castner B.J., Stocking K.L., Reddy P., Srinivasan S., et al. 1997. A metalloproteinase disintegrin that releases tumour-necrosis factor-α from cells. Nature. 385:729–733 10.1038/385729a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanpain C., Fuchs E. 2009. Epidermal homeostasis: a balancing act of stem cells in the skin. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10:207–217 10.1038/nrm2636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaydon D.C., Biancheri P., Di W.L., Plagnol V., Cabral R.M., Brooke M.A., van Heel D.A., Ruschendorf F., Toynbee M., Walne A., et al. 2011. Inflammatory skin and bowel disease linked to ADAM17 deletion. N. Engl. J. Med. 365:1502–1508 10.1056/NEJMoa1100721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blobel C.P. 2005. ADAMs: key components in EGFR-signaling and development. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6:32–43 10.1038/nrm1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg H., Dinh H., Trueblood E.S., Pretorius J., Kugler D., Weng N., Kanaly S.T., Towne J.E., Willis C.R., Kuechle M.K., et al. 2007. Opposing activities of two novel members of the IL-1 ligand family regulate skin inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 204:2603–2614 10.1084/jem.20070157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candi E., Schmidt R., Melino G. 2005. The cornified envelope: a model of cell death in the skin. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6:328–340 10.1038/nrm1619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caubet C., Jonca N., Brattsand M., Guerrin M., Bernard D., Schmidt R., Egelrud T., Simon M., Serre G. 2004. Degradation of corneodesmosome proteins by two serine proteases of the kallikrein family, SCTE/KLK5/hK5 and SCCE/KLK7/hK7. J. Invest. Dermatol. 122:1235–1244 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22512.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalaris A., Adam N., Sina C., Rosenstiel P., Lehmann-Koch J., Schirmacher P., Hartmann D., Cichy J., Gavrilova O., Schreiber S., et al. 2010. Critical role of the disintegrin metalloprotease ADAM17 for intestinal inflammation and regeneration in mice. J. Exp. Med. 207:1617–1624 10.1084/jem.20092366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X., Jin J., Hu L., Shen D., Dong X.P., Samie M.A., Knoff J., Eisinger B., Liu M.L., Huang S.M., et al. 2010. TRP channel regulates EGFR signaling in hair morphogenesis and skin barrier formation. Cell. 141:331–343 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demehri S., Liu Z., Lee J., Lin M.H., Crosby S.D., Roberts C.J., Grigsby P.W., Miner J.H., Farr A.G., Kopan R. 2008. Notch-deficient skin induces a lethal systemic B-lymphoproliferative disorder by secreting TSLP, a sentinel for epidermal integrity. PLoS Biol. 6:e123 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dlugosz A.A., Cheng C., Denning M.F., Dempsey P.J., Coffey R.J., Jr, Yuspa S.H. 1994. Keratinocyte growth factor receptor ligands induce transforming growth factor alpha expression and activate the epidermal growth factor receptor signaling pathway in cultured epidermal keratinocytes. Cell Growth Differ. 5:1283–1292 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doroquez D.B., Rebay I. 2006. Signal integration during development: mechanisms of EGFR and Notch pathway function and cross-talk. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 41:339–385 10.1080/10409230600914344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eissa A., Diamandis E.P. 2008. Human tissue kallikreins as promiscuous modulators of homeostatic skin barrier functions. Biol. Chem. 389:669–680 10.1515/BC.2008.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzke C.W., Baici A., Bartels J., Christophers E., Wiedow O. 1996. Antileukoprotease inhibits stratum corneum chymotryptic enzyme. Evidence for a regulative function in desquamation. J. Biol. Chem. 271:21886–21890 10.1074/jbc.271.36.21886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzke C.W., Bruckner-Tuderman L., Blobel C.P. 2009. Shedding of collagen XVII/BP180 in skin depends on both ADAM10 and ADAM9. J. Biol. Chem. 284:23386–23396 10.1074/jbc.M109.034090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habif T.P. 2009. Clinical Dermatology. Fifth edition Mosby Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA: 1040 pp [Google Scholar]

- Hasson P., Egoz N., Winkler C., Volohonsky G., Jia S., Dinur T., Volk T., Courey A.J., Paroush Z. 2005. EGFR signaling attenuates Groucho-dependent repression to antagonize Notch transcriptional output. Nat. Genet. 37:101–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitomi K. 2005. Transglutaminases in skin epidermis. Eur. J. Dermatol. 15:313–319 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi K., Kimura T., Miyamoto T., Takaishi H., Okada Y., Toyama Y., Blobel C.P. 2007. Cutting edge: TNF-alpha-converting enzyme (TACE/ADAM17) inactivation in mouse myeloid cells prevents lethality from endotoxin shock. J. Immunol. 179:2686–2689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes N.E., Lane H.A. 2005. ERBB receptors and cancer: the complexity of targeted inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 5:341–354 10.1038/nrc1609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine A.D., McLean W.H. 2006. Breaking the (un)sound barrier: filaggrin is a major gene for atopic dermatitis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 126:1200–1202 10.1038/sj.jid.5700365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson L.F., Qiu T.H., Sunnarborg S.W., Chang A., Zhang C., Patterson C., Lee D.C. 2003. Defective valvulogenesis in HB-EGF and TACE-null mice is associated with aberrant BMP signaling. EMBO J. 22:2704–2716 10.1093/emboj/cdg264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagehara M., Tachi M., Harii K., Iwamori M. 1994. Programmed expression of cholesterol sulfotransferase and transglutaminase during epidermal differentiation of murine skin development. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1215:183–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.Y., Jeitner T.M., Steinert P.M. 2002. Transglutaminases in disease. Neurochem. Int. 40:85–103 10.1016/S0197-0186(01)00064-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klipper-Aurbach Y., Wasserman M., Braunspiegel-Weintrob N., Borstein D., Peleg S., Assa S., Karp M., Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y., Laron Z. 1995. Mathematical formulae for the prediction of the residual beta cell function during the first two years of disease in children and adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Med. Hypotheses. 45:486–490 10.1016/0306-9877(95)90228-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch P.J., de Viragh P.A., Scharer E., Bundman D., Longley M.A., Bickenbach J., Kawachi Y., Suga Y., Zhou Z., Huber M., et al. 2000. Lessons from loricrin-deficient mice: compensatory mechanisms maintaining skin barrier function in the absence of a major cornified envelope protein. J. Cell Biol. 151:389–400 10.1083/jcb.151.2.389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramoto N., Takizawa T., Takizawa T., Matsuki M., Morioka H., Robinson J.M., Yamanishi K. 2002. Development of ichthyosiform skin compensates for defective permeability barrier function in mice lacking transglutaminase 1. J. Clin. Invest. 109:243–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacouture M.E. 2006. Mechanisms of cutaneous toxicities to EGFR inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 6:803–812 10.1038/nrc1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacouture M.E., Anadkat M.J., Bensadoun R.J., Bryce J., Chan A., Epstein J.B., Eaby-Sandy B., Murphy B.A.; MASCC Skin Toxicity Study Group 2011. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of EGFR inhibitor-associated dermatologic toxicities. Support. Care Cancer. 19:1079–1095 10.1007/s00520-011-1197-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T.C., Threadgill D.W. 2009. Generation and validation of mice carrying a conditional allele of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Genesis. 47:85–92 10.1002/dvg.20464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luetteke N.C., Qiu T.H., Peiffer R.L., Oliver P., Smithies O., Lee D.C. 1993. TGF alpha deficiency results in hair follicle and eye abnormalities in targeted and waved-1 mice. Cell. 73:263–278 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90228-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann G.B., Fowler K.J., Gabriel A., Nice E.C., Williams R.L., Dunn A.R. 1993. Mice with a null mutation of the TGF alpha gene have abnormal skin architecture, wavy hair, and curly whiskers and often develop corneal inflammation. Cell. 73:249–261 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90227-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maretzky T., Evers A., Zhou W., Swendeman S.L., Wong P.M., Rafii S., Reiss K., Blobel C.P. 2011. Migration of growth factor-stimulated epithelial and endothelial cells depends on EGFR transactivation by ADAM17. Nat Commun. 2:229 10.1038/ncomms1232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrakchi S., Guigue P., Renshaw B.R., Puel A., Pei X.Y., Fraitag S., Zribi J., Bal E., Cluzeau C., Chrabieh M., et al. 2011. Interleukin-36-receptor antagonist deficiency and generalized pustular psoriasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 365:620–628 10.1056/NEJMoa1013068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen P.J., Berger J.E., Meneses J., Phung Y., Pedersen R.A., Werb Z., Derynck R. 1995. Epithelial immaturity and multiorgan failure in mice lacking epidermal growth factor receptor. Nature. 376:337–341 10.1038/376337a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moniaga C.S., Egawa G., Kawasaki H., Hara-Chikuma M., Honda T., Tanizaki H., Nakajima S., Otsuka A., Matsuoka H., Kubo A., et al. 2010. Flaky tail mouse denotes human atopic dermatitis in the steady state and by topical application with Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus extract. Am. J. Pathol. 176:2385–2393 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss M.L., Jin S.-L.C., Milla M.E., Bickett D.M., Burkhart W., Carter H.L., Chen W.J., Clay W.C., Didsbury J.R., Hassler D., et al. 1997. Cloning of a disintegrin metalloproteinase that processes precursor tumour-necrosis factor-α. Nature. 385:733–736 10.1038/385733a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murillas R., Larcher F., Conti C.J., Santos M., Ullrich A., Jorcano J.L. 1995. Expression of a dominant negative mutant of epidermal growth factor receptor in the epidermis of transgenic mice elicits striking alterations in hair follicle development and skin structure. EMBO J. 14:5216–5223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy A., Defamie V., Smookler D.S., Di Grappa M.A., Horiuchi K., Federici M., Sibilia M., Blobel C.P., Khokha R. 2010. Ectodomain shedding of EGFR ligands and TNFR1 dictates hepatocyte apoptosis during fulminant hepatitis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 120:2731–2744 10.1172/JCI42686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy A., Shao Y.W., Narala S.R., Molyneux S.D., Zúñiga-Pflücker J.C., Khokha R. 2012. Notch activation by the metalloproteinase ADAM17 regulates myeloproliferation and atopic barrier immunity by suppressing epithelial cytokine synthesis. Immunity. 36:105–119 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ny A., Egelrud T. 2004. Epidermal hyperproliferation and decreased skin barrier function in mice overexpressing stratum corneum chymotryptic enzyme. Acta Derm. Venereol. 84:18–22 10.1080/00015550310005924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastore S., Mascia F. 2008. Novel acquisitions on the immunoprotective roles of the EGF receptor in the skin. Expert Rev Dermatol. 3:525–527 10.1586/17469872.3.5.525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastore S., Mascia F., Mariani V., Girolomoni G. 2008. The epidermal growth factor receptor system in skin repair and inflammation. J. Invest. Dermatol. 128:1365–1374 10.1038/sj.jid.5701184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peschon J.J., Slack J.L., Reddy P., Stocking K.L., Sunnarborg S.W., Lee D.C., Russell W.E., Castner B.J., Johnson R.S., Fitzner J.N., et al. 1998. An essential role for ectodomain shedding in mammalian development. Science. 282:1281–1284 10.1126/science.282.5392.1281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peus D., Hamacher L., Pittelkow M.R. 1997. EGF-receptor tyrosine kinase inhibition induces keratinocyte growth arrest and terminal differentiation. J. Invest. Dermatol. 109:751–756 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12340759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai S., Bikle D.D. 1991. Role of intracellular-free calcium in the cornified envelope formation of keratinocytes: differences in the mode of action of extracellular calcium and 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3. J. Cell. Physiol. 146:94–100 10.1002/jcp.1041460113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghunath M., Hennies H.C., Velten F., Wiebe V., Steinert P.M., Reis A., Traupe H. 1998. A novel in situ method for the detection of deficient transglutaminase activity in the skin. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 290:621–627 10.1007/s004030050362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin U., Weskamp G., Kelly K., Zhou H.M., Higashiyama S., Peschon J., Hartmann D., Saftig P., Blobel C.P. 2004. Distinct roles for ADAM10 and ADAM17 in ectodomain shedding of six EGFR ligands. J. Cell Biol. 164:769–779 10.1083/jcb.200307137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlöndorff J., Becherer J.D., Blobel C.P. 2000. Intracellular maturation and localization of the tumour necrosis factor alpha convertase (TACE). Biochem. J. 347:131–138 10.1042/0264-6021:3470131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M.R., Werner S., Paus R., Wolf E. 2008. Beyond wavy hairs: the epidermal growth factor receptor and its ligands in skin biology and pathology. Am. J. Pathol. 173:14–24 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevilla L.M., Nachat R., Groot K.R., Klement J.F., Uitto J., Djian P., Määttä A., Watt F.M. 2007. Mice deficient in involucrin, envoplakin, and periplakin have a defective epidermal barrier. J. Cell Biol. 179:1599–1612 10.1083/jcb.200706187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shwayder T., Akland T. 2005. Neonatal skin barrier: structure, function, and disorders. Dermatol. Ther. 18:87–103 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2005.05011.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibilia M., Wagner E.F. 1995. Strain-dependent epithelial defects in mice lacking the EGF receptor. Science. 269:234–238 (published erratum appears in Science 1995 Aug 18;269(5226):909) 10.1126/science.7618085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibilia M., Wagner B., Hoebertz A., Elliott C., Marino S., Jochum W., Wagner E.F. 2003. Mice humanised for the EGF receptor display hypomorphic phenotypes in skin, bone and heart. Development. 130:4515–4525 10.1242/dev.00664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims J.E., Smith D.E. 2010. The IL-1 family: regulators of immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10:89–102 10.1038/nri2691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternlicht M.D., Sunnarborg S.W., Kouros-Mehr H., Yu Y., Lee D.C., Werb Z. 2005. Mammary ductal morphogenesis requires paracrine activation of stromal EGFR via ADAM17-dependent shedding of epithelial amphiregulin. Development. 132:3923–3933 10.1242/dev.01966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratis A., Pasparakis M., Rupec R.A., Markur D., Hartmann K., Scharffetter-Kochanek K., Peters T., van Rooijen N., Krieg T., Haase I. 2006. Pathogenic role for skin macrophages in a mouse model of keratinocyte-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 116:2094–2104 10.1172/JCI27179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surguladze D., Deevi D., Claros N., Corcoran E., Wang S., Plym M.J., Wu Y., Doody J., Mauro D.J., Witte L., et al. 2009. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1 antagonists alleviate inflammatory skin changes associated with epidermal growth factor receptor antibody therapy in mice. Cancer Res. 69:5643–5647 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Threadgill D.W., Dlugosz A.A., Hansen L.A., Tennenbaum T., Lichti U., Yee D., LaMantia C., Mourton T., Herrup K., Harris R.C., et al. 1995. Targeted disruption of mouse EGF receptor: effect of genetic background on mutant phenotype. Science. 269:230–234 10.1126/science.7618084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rooijen N., van Kesteren-Hendrikx E. 2003. “In vivo” depletion of macrophages by liposome-mediated “suicide”. Methods Enzymol. 373:3–16 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)73001-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakita H., Takigawa M. 1999. Activation of epidermal growth factor receptor promotes late terminal differentiation of cell-matrix interaction-disrupted keratinocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 274:37285–37291 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Zinkel S., Polonsky K., Fuchs E. 1997. Transgenic studies with a keratin promoter-driven growth hormone transgene: prospects for gene therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:219–226 10.1073/pnas.94.1.219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood L.C., Jackson S.M., Elias P.M., Grunfeld C., Feingold K.R. 1992. Cutaneous barrier perturbation stimulates cytokine production in the epidermis of mice. J. Clin. Invest. 90:482–487 10.1172/JCI115884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Meyer M., Müller A.K., Böhm F., Grose R., Dauwalder T., Verrey F., Kopf M., Partanen J., Bloch W., et al. 2010. Fibroblast growth factor receptors 1 and 2 in keratinocytes control the epidermal barrier and cutaneous homeostasis. J. Cell Biol. 188:935–952 10.1083/jcb.200910126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J., Garg A., Calhoun C., Feingold K.R., Elias P.M., Ghadially R. 2002. Alterations in cytokine regulation in aged epidermis: implications for permeability barrier homeostasis and inflammation. I. IL-1 gene family. Exp. Dermatol. 11:209–216 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2002.110303.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo A.S., Bais C., Greenwald I. 2004. Crosstalk between the EGFR and LIN-12/Notch pathways in C. elegans vulval development. Science. 303:663–666 10.1126/science.1091639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.