Abstract

Although human pathologies have mostly been modeled using higher mammal systems such as mice, the lower vertebrate zebrafish has gained tremendous attention as a model system. The advantages of zebrafish over classical vertebrate models are multifactorial and include high genetic and organ system homology to humans, high fecundity, external fertilization, ease of genetic manipulation, and transparency through early adulthood that enables powerful imaging modalities. This paper focuses on four areas of human pathology that were developed and/or advanced significantly in zebrafish in the last decade. These areas are (1) wound healing/restitution, (2) gastrointestinal diseases, (3) microbe-host interactions, and (4) genetic diseases and drug screens. Important biological processes and pathologies explored include wound-healing responses, pancreatic cancer, inflammatory bowel diseases, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and mycobacterium infection. The utility of zebrafish in screening for novel genes important in various pathologies such as polycystic kidney disease is also discussed.

1. Introduction

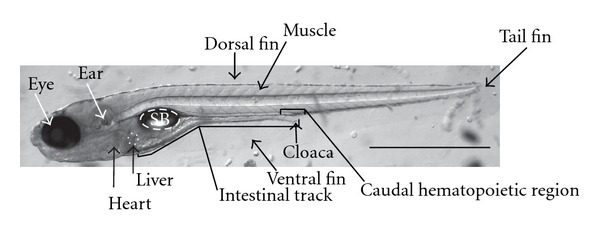

Investigators have long utilized reductionist systems and animal models to mimic and study basic processes regulating cellular biology, organ function, and host homeostasis. While much work has been accomplished and continues to be undertaken in higher mammalian systems such as mice, rats, and rabbits, important discoveries have also been made using invertebrate systems such as Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster. For example, RNA interference technology was first discovered in C. elegans [1], as was the initial caspase enzyme, caspase-1 (ced-3 in C. elegans) [2]. Similarly, it was in Drosophila melanogaster that the innate signaling Toll-like receptors (TLRs) were first identified via the discovery of the Toll gene, as was its linkage to the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) signaling cascade [3]. In the last ~15 years, there has been a growing appreciation for the vertebrate organism Danio rerio (zebrafish) as a tool to study human disease [4]. As opposed to C. elegans and Drosophila melanogaster, zebrafish is a vertebrate organism with physiological and anatomical characteristics of its higher organism counterparts (see Figure 1 for a diagram of larval zebrafish anatomy), while maintaining the ease of use of a lower organism. The characteristics of zebrafish that make them desirable tools for the study of embryogenesis/development also make them useful for the study of human pathologies. Zebrafish have a fully mapped genome (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/D_rerio/), which has significant homology with the human genome, including noncoding regions (~60 per gene globally across all genes) [5] suggesting that numerous genes involved in human diseases could be matched in the zebrafish genome. Reverse (morpholino knock-down, Targeting Induced Local Lesions in Genome—TILLING [6]) and forward genetic (mutagenesis, transgenic) approaches are well established and commonly used to manipulate and characterize zebrafish gene function.

Figure 1.

Diagram of zebrafish anatomy. A representative image of a transparent, 6 dpf larvae captured with brightfield microscopy. Organs and anatomical features are denoted in the figure. SB: swim bladder. Scale bar is 1 mm.

Zebrafish are highly fecund and breed rapidly; a pair of zebrafish produces over 100 embryos per clutch that are usable for larval experiments as early as 3 days post fertilization (dpf). These larvae are transparent through 7 dpf, and this can be extended to up to 9–14 dpf with the addition of the melanocyte inhibitor phenylthiourea. Moreover, the recent generation of transparent adult zebrafish such as the Casper line adds new imaging possibilities [7]. The transparency of zebrafish, in conjunction with sophisticated utilization of fluorescent technology to mark signaling proteins or cellular entities, allows for powerful time-lapse imaging of biological and disease processes. Additionally, the vertebrate zebrafish has many features commonly found in mammals, including an innate immune system composed of neutrophils, NK cells, and monocyte/macrophages with functionality by 48 hours post fertilization (hpf) [8, 9] and an adaptive immune system that is fully functional at 4–6 weeks post fertilization [10]. The adaptive immune system is highly analogous to that of mammals, with T cells and B cells that have Rag-dependent V(D)J recombination (reviewed extensively in [9]). Finally, the zebrafish research community benefits from an up-to-date database of techniques, genetic strains, and other useful resources at http://zfin.org/.

In this paper, we focus our discussion on larval and adult zebrafish models that recapitulate human diseases, focusing on four separate branches of pathology: wound healing/restitution, gastrointestinal disease, microbe-host interactions, and genetic diseases and drug screens.

2. Wound Healing/Restitution

Wound healing represents a critical biological response of injured tissues and organs. Events causing epithelial injury and barrier breakdown initiate a biological response known as “restitution”, which is aimed at resealing the damaged region and reestablishing host homeostasis. This “wound healing” response involves migration of epithelial cells toward the injured regions as well as epithelial cell proliferation to replenish the cell pool. Understanding the cellular and molecular mechanisms regulating this response could have profound translational impact for patients suffering from chronic inflammation, ischemia/hypoxia, burn injury, and cancer. The powerful imaging modalities available to zebrafish researchers alongside their ease of genetic manipulation make this vertebrate system an ideal model for studying wound healing response to various injuries [11]. Additionally, the ability of zebrafish to regenerate both limbs and cardiac tissue [12] makes them a powerful animal model for understanding the molecular mechanisms involved in regenerative signaling.

The most popular zebrafish injury model is the larval tail wounding model, where a segment of the tail fin is resected. Using this injury model with transgenic zebrafish expressing EGFP under the transcriptional controlled of the neutrophil-specific myeloperoxidase (MPO) promoter—Tg(BACmpx:GFP)i114—investigators studied real-time neutrophil chemotaxis to the site of injury [13]. In this study, they observed retrograde chemotaxis of neutrophils toward the vasculature alongside where injury resolution was observed, suggesting for the first time that retrograde chemotaxis may play an important role in the resolution phase of the inflammatory response [13]. To determine the function of the reactive oxygen species H2O2 in the wound healing response, investigators injected mRNA encoding for the hydrogen peroxide sensor HyPer to one-cell stage developing zebrafish embryos [14]. Upon tail wounding of 3 dpf larvae, the HyPer sensor demonstrated increased H2O2 production along a gradient decreasing away from the wound site, which signaled leukocyte chemotaxis to the injured location [11]. Using pharmacological and morpholino blockade, the authors showed that generation of the H2O2 gradient is dependent on the activity of the dual oxidase (duox) gene. This HyPer reporter system has also been utilized in the study of neuronal regeneration, an important area of study for the treatment of many human diseases. H2O2 produced by injured keratinocytes was shown to induce somatosensory axonal regeneration in zebrafish. Similar to the tail fin wounding model, neuronal regeneration required activation of duox [15]. Moreover, H2O2 administration promoted axonal regeneration following neuronal injury, even without accompanying keratinocyte injury [15]. These results expand the understanding of posttraumatic nerve injury and subsequent loss of limb function in humans. The healing-enhancing properties of H2O2 have since been extended to studies in both rabbits [16] and horses [17] as well as one reported case study in a human patient [18].

Beyond cutaneous wounds, zebrafish have been used for the ability to regenerate cardiac tissue. Unlike mammals, which form scars and do not regenerate cardiac tissue following injury, zebrafish are able to fully regenerate their heart within 2 months after 20% ventricular resection [19]. This ability for zebrafish to overcome scar formation requires activation of Mps1, a mitotic checkpoint kinase [19]. Additionally, cardiac regeneration involves upregulation of wound healing genes and proliferative factors including apoeb, vegcf, and granulina (all of which have human analogs) and likely activation of platelet-derived growth factor B signaling [20]. Cardiac regeneration studies in zebrafish could produce novel paradigms and identify unique pathways/targets with profound translational impact for patients suffering from ischemic heart disease.

3. Gastrointestinal Diseases

The zebrafish gastrointestinal system is highly homologous to that of mammals, containing a liver, pancreas, gall bladder, and a linearly segmented intestinal track with absorptive and secretory functions [21, 22]. The intestinal epithelium displays proximal-distal functional specification and contains many of same epithelial cell lineages found in mammals including absorptive enterocytes, goblet cells, and enteroendocrine cells [21, 22]. Enterocytes have a basolateral nuclei and form tight junctions, apical microvilli, and an intestinal brush border [23]. In the last decade, numerous gastrointestinal pathologies have been modeled in the zebrafish, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Zebrafish gastrointestinal models of pathology.

| Model | Mechanism of pathology | Human relevancy/key features | Key references |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pan-GI neoplasias | Heterozygotic APC mutation | APC mutations drive spontaneous and genetic intestinal adenocarcinomas. | Haramis et al., 2006 [24] |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Thioacetamide ± HCV-core-protein-zebrafish | Human genetic overlap. Rising prevalence of HCV-driven HCC in humans. | Lam and Gong, 2006 [25] Rekha et al., 2008 [26] |

| Pancreatic cancer | Transgenic ptf1a-KRAS zebrafish | Recapitulates hedgehog signaling aberrations found in humans. Elucidates a potential cellular origin for pancreatic cancers. | Park et al., 2008 [27] |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | TNBS in the media of zebrafish larvae | Model inflammatory and goblet cell hypertrophy. Responds to bacterial status and IBD medications. | Flemming et al., 2010 [28] Oehlers et al., 2011 [29] |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Oxazolone enema in adult zebrafish | Goblet cell depletion and eosinophil infiltration. Responds to antibiotic therapy. | Brugman et al., 2009 [30] |

| NAFLD | Mutation in a novel gene: foigrhi1532b. Alternative model involves chemical induction with thioacetamide |

Large lipid filled hepatocytes and cellular apoptosis; pathology linked to ER stress responses. Alternative model generates a fatty liver and hepatocyte apoptosis. | Cinaroglu et al., 2011 [31] Amali et al., 2006 [32] (alternative model) |

| Alcoholic liver disease | 2% ethanol to the water of 4 dpf zebrafish for 32 days | Hepatomegaly and steatosis, with upregulation of genes involved in toxic alcohol metabolism. Model is sensitive to sterol regulatory binding protein, important in human disease. | Passeri et al., 2009 [33] |

Abbreviations: GI: gastrointestinal; APC: adenomatous polyposis coli; HCV: hepatitis C virus; TNBS: 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid; IBD: inflammatory bowel diseases; NAFLD: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; ER: endoplasmic reticulum.

Interestingly, a forward genetic mutagenesis screen (N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU), see section five) generated zebrafish mutants that develop spontaneous intestinal, pancreatic, and hepatic neoplasias [24]. These mutants were later found to be heterozygotic for a truncated form of APC, thereby leading to accumulation of nuclear β-catenin and increased expression of downstream genes such as cmyc and axin2 [24]. Adding the carcinogen 7, 12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene to these mutant zebrafish increases the frequency of tumor development. Since germ-line-truncated APC mutations in both humans [34, 35] and mice [36] result in the spontaneous development of a large numbers of intestinal polyps, the APC zebrafish model could be useful in genetic, drug screening, and toxicology studies.

There are roughly 24,000 new cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) annually in the United States, resulting in over 18,000 deaths per year [37]. Worldwide, the disease incidence can be as much as 30-fold higher due to the increased prevalence of hepatitis infections [38]; globally estimated 564,000 new cases occur per year, accounting for 5.6% of all human cancers [38], and resulting in similar rates of mortality as seen in the USA [38]. Oncogenomic profiling of liver tumors showed a significant overlap between human and zebrafish in 132 genes [25]. These genes included those involved in β-catenin and Ras-MAPK signaling pathways as well as genes implicated in cellular adhesion, apoptosis, and liver-specific metabolism found in both organisms [25]. HCC can be induced in zebrafish with the liver toxin thioacetamide, resulting in HCC-related pathology within 12 weeks of exposure. The timeline of thioacetamide-induced HCC could be significantly accelerated (6 versus 12 weeks) by using transgenic fish expressing the hepatitis C virus (HCV) core protein (HCP-transgenic fish) [26]. The increasing prevalence of HCC in humans has been attributed to the rise of HCV infection [39], in particular through the oncogenic action of the HCV core protein [40], making this model particularly relevant to human disease.

Pancreatic cancer represents the fourth most common cause of cancer-related mortality in the western world, likely due to limited diagnostic tools and inability to survey the disease. Exocrine pancreatic cells are responsible for more than 95% of pancreatic cancer [37]. The cell population in the pancreas that gives rise to human exocrine pancreatic cancer remains unknown and investigators have turned to zebrafish models to investigate this important question. Transgenic zebrafish were generated using a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) approach that expressed EGFP-KRAS fusion protein under the control of the zebrafish pancreatic locus ptf1a (Tg(pft1a:EGFP-Hsa.KRASG12V)jh7 [27]. Using these fish, investigators found that while normal pancreatic cell progenitors differentiated normally, KRAS-transgenic fish had blocked cellular differentiation, producing a pool of undifferentiated progenitors that progressed to invasive pancreatic cancer over a course of 3 to 9 months. These cancer cells also had increased expression of multiple hedgehog genes (shh, dhh, ihha, ihhb) as well as the downstream hedgehog targets Ptc2, ptc1, and gli1. This aberrant signaling pattern seen in these pancreatic tumor cells was also typical of human pancreatic cancer [27]. This zebrafish model established for the first time that oncogenic exocrine pancreatic progenitor cells could be the cellular origin for pancreatic cancer.

Outside of cancer models, one area of gastrointestinal disease that has received significant attention in recent years is the development of zebrafish models of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). In humans, IBD is the result of dysregulated interactions between a genetically susceptible host and their commensal gut microbiota [41–43]. IBD is primarily a disease of the Western world; it affects 1.4 million Americans and there is no cure for the disease [44]. Outside of North America, similar disease burdens are seen in Europe but are ~3-fold lower in Asia and the Middle East, with the exception of Japan [45]. Pharmacological treatment centers around the use of anti-inflammatories and immunosuppressants, and surgical management of the disease is also possible though not always curative [46]. Numerous chemicals and genetic approaches are currently used by the IBD research community to study this pathology. These models mimic various aspects of the disease, such as disrupted barrier function and impaired innate and adaptive immune responses [47, 48]. Among the chemical models, the hapten oxazolone has been used for studies of acute intestinal inflammation. This murine model consists of rectal administration of a single dose of oxazolone dissolved in ethanol, resulting in an acute colitis lasting up to 10 days, with peak inflammation at 2 days post administration in mice [49]. The model is characterized by a strong Th2-dependent immune response that can be abrogated by IL-4 neutralizing antibodies and has similar characteristics to human ulcerative colitis [48].

Investigators have tried to adapt the hapten oxazolone model of colitis to adult zebrafish. Brugman et al. showed intestinal epithelial damage and goblet cell depletion in oxazolone-treated fish within 5 hours of treatment, which lasts for up to 7 days [30]. This was accompanied by eosinophil infiltration into the intestine with increased il1b, tnf, and il10 gene production compared to untreated zebrafish. The inflammatory phenotype was reduced by the administration of the gram-positive-specific antibiotic vancomycin, suggesting a role for commensal bacteria in the inflammatory process of this model. The main constraint of this model is the need to use adult, nontransparent zebrafish which severely limits imaging capability. In addition, the need to rectally administer each individual zebrafish with oxazolone represents a technical challenge.

The hapten 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS) is another popular mammalian model of colitis characterized by a Th1-driven immune response [48] that is used for the study of both acute and chronic intestinal inflammation. In the acute model, TNBS is dissolved in ethanol and rectally administered in a single dose, while the chronic model can have multiple administrations weekly over a period of months [50]. The ethanol is responsible for disrupting the intestinal barrier while the TNBS serves to activate the immune system [48]. Two research groups have developed a larval model of colitis by exposing 3 dpf zebrafish for 3–5 days to TNBS in the fish media [28, 29]. Using the MPO reporter strain (Tg(BACmpx:GFP)i114) these investigators noticed neutrophil infiltration throughout the zebrafish [13], gut-specific increases in il1b expression, altered intestinal lipid metabolism, goblet cell hypertrophy, and intestinal shortening. This larval TNBS model presents several advantages, including a dose-dependent phenotype, a sensitivity to antibiotics treatment, and a response to anti-inflammatory agents (5-ASA and prednisolone) widely used to treat human IBD [29]. However, the intestinal histopathologies are poorly characterized in this model. In addition, the inflammatory component appears mostly to be nonintestine specific. Furthermore, no intestinal epithelial cell damage is observed histologically [29], suggesting a lack of significant intestinal injury. Finally, it is unclear how a hapten could cause an inflammatory reaction in larvae missing a functional adaptive immune system.

We have recently established a model of epithelial injury in zebrafish using the NSAID glafenine [51]. Administration of glafenine to 5 dpf zebrafish for 12 hours results in a dramatic increase in intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis. This intestinal-specific apoptotic response is mediated by induction of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and is accompanied by attenuation of the unfolded protein response (UPR) coupled to an improper activation of downstream UPR mediators such atf6 and s-xbp1. Interestingly, loss of XBP1 in IECs results in the development of spontaneous enterocolitis in mice [52] and polymorphisms of this gene are associated with human IBD [53].

Chronic liver disease is responsible for over 25,000 deaths annually in the United States and represents the tenth leading cause of death, with a prevalence of over 5.5 million patients in 1998 [54] and that has since been estimated to affect up to 30% of the US population [55]. In the UK, the picture is grimmer, as it is the fifth leading cause of death [56]. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a highly prevalent form of severe chronic liver disease, affecting 3% of all adults in America [57]. It also has significant associated mortality, with a 5-year survival of 67% and 10-year survival of 59% [57]. Additionally, up to one-third of all Americans have some level of NAFLD [56]. Outside of the USA, where obesity is less prevalent, rates are also increasing. In Italy, which is traditionally considered low risk, an incidence of NAFLD of 20–25% of the population has been recently been reported [56]. In China and Japan, the disease incidence has been reported at 15% and 14% of the population, respectively [56]. There is no identifiable cause of NAFLD, but the pathology is linked to obesity, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. Treatment involves managing these complex etiologies, and pharmacological therapies specific for NAFLD are not available for these patients [57]. Consequently, significant work has been invested to develop reliable zebrafish larvae models of liver pathology that could be easily utilized for drug targeting and screening.

The most characterized zebrafish model of NAFLD involved a forward genetic screen using viral insertion and screening for hepatomegaly. In the case of the NAFLD model, a 172 bp gene trap cassette was found to be inserted in the intron between exons 11 and 12 of the recently discovered zebrafish gene foie gras (foigr) [58], which results in a frame shift mutation, and generation of a stop codon. This mutation (foigrhi1532b) results in the development of steatosis (fatty liver disease) resembling human NAFLD, characterized by large lipid filled hepatocytes and cellular apoptosis in larvae as young as 5 dpf [58]. However, the exact function of this gene, which is highly conserved across species including humans, is not yet determined. Further studies with the foigr mutant have shown that the apoptosis observed involves increased ER stress and is regulated in part through the UPR gene atf6. Morpholino blockade of atf6 ameliorates liver injury during chronic ER stress in the foigr mutants [31]. However, atf6 blockade potentiates steatosis during acute ER stress induced by the toxin tunicamycin [31], suggesting that atf6 may have variable effects in different phases (acute/chronic) of liver injury. Hepatic steatosis has also been induced in zebrafish larvae using thioacetamide [32]. Investigators have showed that administration of 0.025% thioacetamide into the fish media at 3 dpf resulted in liver damage by 5 dpf, characterized by increased accumulation of fatty droplets, hepatocyte apoptosis, and upregulation of apoptotic genes such as bad, bax, p-38a, caspase-3 and 8, and jnk-1. Overall, the availability of NAFLD zebrafish models is burgeoning, and they are poised to be screened for pharmacological compounds that could for the first time effectively treat this disease.

Alcoholic fatty liver disease (ALD) is estimated to be involved in over 50% of all deaths due to liver failure secondary to liver cirrhosis, but accurate estimates for prevalence are unavailable [54]. Binge drinking leads to transient fatty liver disease, but chronic alcohol consumption can lead to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and steatohepatitis [59]. An ALD model has also been developed in zebrafish with administration of 2% ethanol to the water of 4 dpf zebrafish for 32 days. This regimen results in hepatomegaly and steatosis, alongside upregulation of hepatic cyp2e1, sod, and bip gene expression—indicating hepatotoxic metabolism of the ethanol [33]. Importantly, ethanol-induced steatosis was prevented by morpholino blockade of the sterol regulatory binding protein (Srebps). Because Srebps activation is important in chronic alcoholic liver disease [33] in humans, the zebrafish ALD model could be utilized to identify new therapeutic mechanisms and to screen for therapeutic agents.

4. Microbe-Host Interactions

The ability to generate germ-free and gnotobiotic zebrafish [60] has led to an increasing interest in understanding cellular and molecular mechanisms of microbial-host interactions using zebrafish. Microbial-host interactions have received significant interested in recent years and have been implicated in a wide variety of human diseases, including CRC [61], IBD [42, 43], obesity and diabetes [62], intestinal healing [63], irritable bowel syndrome [64], and inflammatory nociception [65]. Zebrafish are host to gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, mycobacteria, protozoa, and viruses [66], also allowing for their use as a model for infectious diseases. In most cases, microorganisms associated with these pathologies are not intrinsically pathogenic but are rather part of the normal, commensal biota. The organ exposed to the highest amount of microorganisms in the human body is the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, especially the distal ileum and colon. Because of the high prevalence of bacteria and bacterial products in the GI tract, investigators have studied mechanisms controlling homeostasis in the face of such highly antigenic materials. The zebrafish GI tract also harbors the highest concentration of bacteria and as such represents an interesting model to study bacterial/host interactions.

Bacteria and their associated products such as DNA, RNA, and membrane structures (peptidoglycans, LPS—lipopolysaccharide) are typically detected by a series of innate sensors that are evolutionary conserved. A survey of the zebrafish genome has identified numerous innate sensors from the TLR and the Nod-like receptor family as well as their associated signaling pathways [67]. An almost complete set of TLRs (TLR1-5, 7-9, 21 [68]) exist in zebrafish, as do the intracellular sensors Nod1 and Nod2 [69]. Associated innate signaling proteins have also been identified in zebrafish such as myeloid differentiation primary response gene (MyD88) [68, 70], TIR domain-containing adaptor inducing IFN-β (TRIF) [71], and NF-κB [72, 73].

The most studied bacterial product is arguably the gram-negative-derived LPS. In mammals, LPS is detected by TLR4, in association with the coreceptors MD2 and CD-14 [74]. Once engaged, TLR4 recruits the adapter protein Myd88 or TRIF to propagate the signal to NF-κB [75] and the interferon responsive factor (IRF) 3, respectively [76]. This signaling cascade plays a critical role in host response to microbes and microbial products. As in humans, high doses of LPS are toxic to zebrafish [77]. Studies using commensal and germ-free zebrafish established that intestinal alkaline phosphatase (iap), known to detoxify the endotoxic lipid moiety A of LPS in mammals, is induced following microbial colonization [77]. Knockout of iap resulted in excessive intestinal neutrophil infiltration, a process involving functional myd88 and tnfr as determined by morpholino blockade [77].

Another important TLR system is TLR5, which detects flagellin and activates various signaling pathways including NF-κB [74]. Similarly to mammals, zebrafish detect flagellin (Salmonella derived in these experiments) to induce multiple matrix metalloproteinase genes as well as the inflammatory markers il1b, il8, ifn, and cxcl-C1c [78]. Morpholino blockade showed that flagellin-induced Il1b and metalloproteinase 9 (mmp9) were myd88 dependent whereas ifn and il8 were activated through another signaling system [78].

The functions of some of these TLR downstream signaling adaptors have also been studied in zebrafish. Both red and green transgenic Myd88 reporter strains such as Tg(myd88:EGFP)z163 and Tg(myd88-DsRED2)z164 have been developed [70]. These strains have been crossed to both macrophage (Tg(lyz:DsRED2)nz50 [79]) and neutrophil (Tg(BACmpx:GFP)i114 [13]) reporter strains to monitor myd88 signaling. Studies with these dual-reporter fish demonstrated that MyD88 colocalized with both macrophages and neutrophils and that these myd88-expressing leukocytes migrated to wound sites and were involved in bacterial phagocytosis [70].

Another downstream mediator of LPS signaling, acting independently of MyD88, is TRIF. While zebrafish TRIF shares only 32% homology with the human protein, like in mammalian systems it can induce IFN and NF-κB luciferase-reporter responses as seen using an overexpression system in human HEK293T cells [71]. Interestingly TRIF-dependent gene induction through the TLR4 pathway was found to be nonfunctional in experiments with adult zebrafish stimulated with LPS [71]; however, this is to be expected given that zebrafish TLR4 paralogues (tlr4a and tlr4b) do not recognize LPS [80, 81].

Outside of the TLRs, the intracellular sensors Nod1 and Nod2 are critical innate signaling systems in mammals. Importantly, Nod2 was the first innate signaling molecule to be genetically linked to Crohn's disease susceptibility [82]. The exact protective role of Nod proteins in mammals is not fully understood but defective bacterial killing appears to be an important factor [82–84]. Both nod1 and nod2 genes are expressed in IECs and neutrophils of zebrafish. Functional studies using morpholino blockade showed that Nod2 plays an important role in setting host antimicrobial properties [69]. Interestingly, Nod1 or Nod2 depletion resulted in increased susceptibility to Salmonella infection in a zebrafish embryonic infection model [69]. This study suggests that the antimicrobial properties of Nod2 are conserved in zebrafish.

As mentioned previously, NF-κB signaling is an important effector pathway downstream of numerous innate sensor systems [85]. Colonization of germ-free NF-κB; EGFP reporter zebrafish Tg(NFkB:EGFP)nc1 with a commensal microbiota induced NF-κB activation and expression of NF-κB target genes including complement factor b (cfb) and serum amyloid a (saa) in intestinal as well as in extraintestinal tissues of the GI tract [86]. Activation of NF-κB signaling in zebrafish indicates an important role of this transcription factor in maintaining host homeostasis that is conserved across species. The ability to longitudinally study NF-κB activation in a cell-type specific fashion in response to various microbial stimuli makes the zebrafish a powerful system to decipher complex host-microbe interaction. Overall, the recent development of the aforementioned technologies makes the study of microbial-host interactions in zebrafish a burgeoning area of research.

Response to infection is another area of microbial-host interaction that has received significant attention in zebrafish. The most studied and prominent zebrafish infectious model is the M. marinum model, which is highly analogous to the human infectious agent M. tuberculosis, the etiologic agent for Tuberculosis (TB). TB is a growing epidemic worldwide, with over 83 million cases reported between 1990 and 1999, resulting in over 3 million deaths annually [87]. Many strains of the infectious bacteria are becoming drug resistant, resulting in an increase in global disease burden, including in the Unites States [88]. Finding new drugs to combat the ongoing threat of TB is consequently essential, as the disease can no longer be contained with current medications [89]. Coincubation of M. marinum with 5 hpf embryos results in the formation of macrophage-driven granulomas within 5 dpf [90], a hallmark of TB pathology. In vivo imaging and macrophage depletion showed that granulomas, traditionally thought to be a host-protective mechanism, may in fact be a source of early TB tissue dissemination by passing M. marinum into uninfected macrophages during phagocytosis [91, 92]. Consequently, this system has provided novel insights into the pathological mechanisms of TB infection and its interactions with the host immune system and is poised to be used as a drug screen to identify novel anti-TB compounds.

Other pathogens have also been studied in zebrafish. These include S. aureus, S. pyogenes, and S. typhimurium. These and other infectious models in zebrafish have recently been reviewed in detail by Meeker and Trede [9]. Although very informative, these studies were not performed using a natural route of infection but rather by using direct delivery (injection) into embryos at various developmental stages. However, oral gavage technology in larvae would likely improve the physiological relevance of infectious models perform in zebrafish. Another limitation of zebrafish infection models is the difference in host temperature; zebrafish and their natural pathogens exist at a temperature of 28°C, while many human-relevant pathogens are only infectious at 37°C [9]. Finally, there is some evolutionary divergence in TLR signaling that must be taken into account when working with this organism. Specifically, in contrast to mammals, LPS is not sensed by zebrafish TLR4 and the sensor negatively regulates MyD88 signaling [80]. Despite these limitations, zebrafish remain a powerful tool for studying microbe-host interactions [67].

5. Genetic Diseases and Drug Screens

Because of their high fecundity, transparency, and ease of imaging, zebrafish are particularly well suited for genetic screening approaches. Forward and reverse genetic approaches can be undertaken to generate new zebrafish phenotypes and identify new genes of interest with potential relevance to human disease phenotypes. Zebrafish disease models can also be screened in a cost- and time-effective manner to discover disease-suppressing compounds. Using a whole organism is a particularly appealing aspect of zebrafish-based screens, since complex cell-cell and organ-organ interactions are kept intact.

There are two main approaches to forward-genetic screens in zebrafish that have been undertaken thus far. The first involves exposing males to the mutagen ethylnitrosourea (ENU) and then screening for a phenotype [93, 94] shared by all mutants, such as renal cysts or heart failure. ENU is an alkylating agent that typically induces A→T base transversions. Zebrafish are relatively resistant to the ENU toxic side effects, allowing for higher dosages and thus increased rates of mutation [95]. An alternative mutagenesis approach employs random retroviral insertion [96, 97]. While this retroviral method is only one-ninth as efficient at generating a mutation as the ENU approach, it circumvents the need for positional cloning by tagging each insertion event, saving significant screening effort once a phenotype is found.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) affects 1 in 3500 males and causes progressive muscle degeneration that can lead to death. DMD is the result of mutations in the sarcolemmal protein dystrophin located on the X-chromosome [98]. During an ENU screen of zebrafish [94], a mutation referred to as sapje [99] was discovered. This mutation was later found to be located in the zebrafish Duchenne muscular dystrophy (dmd) gene and causes progressive muscular degeneration in zebrafish larvae [100]. Electron microscopy showed that muscular degeneration was the result of failure to form proper muscle attachments at the myotendinous junction. This pathological mechanism was hypothesized to occur in mammals but was lacking concrete evidence, making the zebrafish a novel system for studying the pathophysiology of this devastating disease.

The most common form of heritable polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is autosomal dominant PKD. This disease affects more than 1 in 1000 live births and approximately 10% of patients with PKD will require kidney transplant due to renal failure [101]. PKD has been linked to defects in primary cilia formation and function in humans [101]. This disease has also been successfully modeled in zebrafish by using retroviral insertion mutagenesis and screening for cystic kidneys in 5 dpf larvae [102]. The screen discovered 12 genes whose loss formed cysts in the glomerular-tubular region, including two already associated with human disease (vhnf1 and pkd2), demonstrating genetic and phenotypic homology between humans and zebrafish. Three of the 10 remaining genes are homologues of Chlamydomonas (a genus of green algae) genes, which encode components of intraflagellar transport particles involved in cilia formation [102], but have yet to be analyzed in human PKD patients. The other 7 genes discovered provide completely novel targets for studying the underlying genetics and mechanisms of PKD, as many of the genes that can result in PKD remain unidentified in humans [101].

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is the cause of at least half of the 5.8 million heart failure cases in the USA, typically resulting from prior heart damage due to a myocardial infarction or an infection [103]. Worldwide, DCM is the leading indicator for heart transplant [104], with incidences to be as high as 9.6 per 100,000 person-years in Europe [104] and China [105]. DCM results in poor heart function that eventually leads to death [103]. ENU zebrafish screens discovered numerous fish with cardiac abnormalities [93, 106, 107]. Two of these mutants, sih and pickwickm171, were found to have dilated hearts with thin walls and defective contractility [108, 109]. Further analysis showed that the sih (silent heart) mutants had a mutation in cardiac troponin T gene [108], while the pickwickm171 mutants had a mutation in the titin gene [109]. Since both of these genes are known to be important in human DCM, these mutants zebrafish represent interesting and complementary models to study this pathology.

All of the aforementioned models demonstrate that forward genetic screens in zebrafish can generate specific phenotypes that are highly homologous to human diseases. Further analysis of these mutants almost invariability leads to the identification of a gene with high homology and relevance to corresponding human disease.

Targeted, reverse genetic approaches are also quite successful in generating models of disease, especially if a homolog exists between the human gene(s) driving the disease and the zebrafish. One disease that has recently been modeled in zebrafish using a reverse-genetic approach is Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS), a rare (1 : 4,000,000 people) premature senescence syndrome that generally results from sporadic mutations that disrupts conversion of prelamin A to mature lamin A [110]. HGPS patients have markedly aberrant development characterized by lipodystrophy, osteolysis that is most pronounced in the cranium, and coronary dysfunction [110]. The mean life expectancy for patients with HGPS is less than 13 years. In zebrafish, investigators were able to use a combination of directed loss of function mutations and morpholino knockdowns of prelamin and progerin to generate zebrafish that were able to live to adulthood (though with shortened lifespans). These fish had both phenotypic and molecular signs of early senescence, including lipodystrophy, aberrant musculature and craniofacial skeletal structure, increased cellular apoptosis, and cell-cycle arrest [111]. These phenotypic manifestations align remarkably well with those seen in human HGPS, demonstrating a proof of concept for reverse genetic approaches to developing zebrafish models of human diseases.

Some of the mutants generated during forward-genetic screens have been subsequently subjected to drug screening methodologies. The ability to rapidly and easily image large numbers of developing zebrafish makes them highly tractable as a preclinical system for drug screens [112]. A prototypical example of drug screening in mutant zebrafish discovered with the ENU forward-genetic approaches involves the gridlock (grl) mutant. The grl mutant lacks blood flow to the posterior trunk and tail due to a localized block in caudal blood flow at the base of the dorsal aorta [113]. This model has many characteristics similar to the human congenital disease coarctation of the aorta, making it of significant clinical interest. Coarctation of the aorta involves narrowing of the aorta that affects 1 in 2,500 live births [114]. It is the fifth most common form of congenital heart defect, and without surgical treatment the mean age of survival is only 31 years of age [114]. Surgical intervention can prevent early death, but significant morbidity, usually in the form of hypertension, can persist and results in decreased life expectancy [114]. Unfortunately, no clear etiology of the disease exists, and the grl model in zebrafish is the best animal model currently in existence for the study of this disease [114].

The grl zebrafish has a hypomorphic mutation in the hey2 gene, a basic helix-loop-helix protein involved in aortic development [115]. Gene titration studies using morpholino technology demonstrated that dose-dependent loss of this gene results in ablation of progressively larger sections of the aorta and expansion of the contiguous region of vein [116]. A pharmacological screen, assessing restoration of blood flood and survival of larvae using bright-field microscopy, found that two structurally related compounds (GS3999 and GS4012, unknown targets) promoted activation of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathway and were able to rescue the phenotype [117]. Another unrelated screen found that phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitors were also able to rescue the phenotype by driving VEGF activation [118]. This included the uncharacterized flavone GS4898, a structurally similar compound to the PI3K inhibitor LY294002, and the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin. This work also demonstrated for the first time that ERK signaling in embryos drives aortic differentiation, while activation of PI3K signaling produces a venous fate. These findings have since been recapitulated in a murine system and have provided new insights into arterial morphogenesis [119] as well as generated some of the first insights into the underlying mechanisms behind coarctation of the aorta in humans.

A pair of robust screens has also been performed to evaluate compounds known to induce prolonged QT intervals in humans in the hopes of developing a preclinical cardiac toxicity screen. Cardiac QT elongation, which can cause the fatal heart arrhythmia known as Torsade de Pointes, is required to be evaluated in clinical drug trials [120] and thus these screens are of great clinical importance. Two such screens to evaluate bradycardia, atrioventricular blockade and arrhythmias in zebrafish have been performed thus far [121, 122]. In the first study 100 biologically active compounds were screened and 18 of the 23 that caused arrhythmias in humans were also positive in the zebrafish, while postscreen analysis showed that poor absorption explained 4 out of 5 of the false-negatives [122]. Additionally, the combination of erythromycin and cisapride was also positive during screening while each drug alone was not, recapitulating a known drug-drug interaction that causes arrhythmias in humans. Consequently, the zebrafish hold significant promise to be used as a screen to evaluate new drugs for their potential to generate this serious and often fatal side effect.

6. Overall Limitations

The use of zebrafish as a model organism for studying human disease is a relatively new and emerging field of research. Consequently, the number of available zebrafish strains and facilities that house zebrafish is much smaller than for well-developed model higher vertebrate organisms such as the mouse. Additionally, very few validated zebrafish reagents such as antibodies and cell lines are available to the research community. This significantly curtails the in-depth investigation of molecular and cellular details implicated in a given phenotypes.

Zebrafish also have numerous duplicate genes [123], which significantly complicate generation of knockout strains using either forward or reverse-genetic approaches. Forward-genetic approaches that disrupt one gene copy likely will not disrupt the second copy, and duplicate genes also make targeted knockout strategies more difficult as both copies must be deleted. Additionally, while the zebrafish genome has been fully sequenced, the annotation is still limited and more of a work in progress. Furthermore comparative genomic analyses between zebrafish and the human or murine genome counterparts have yet to be performed.

Zebrafish also have environmental conditions that differ substantially from humans. They must be raised in water with specific ionic concentrations and temperature (28°C). Consequently, some water-insoluble small molecules cannot be administered to zebrafish because carrier solvents (such as EtOH or DMSO) would reach toxic levels before solubility is achieved. Additionally, since drugs are administered directly to the fish media, bathing the entire fish in the test compound can result in nondesired toxic side effects. An example in our hands was the attempt to use dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) to induce colitis in larval zebrafish. At concentrations as low as 0.01% (v/v) the surfactant properties of the DSS choked the gills of the zebrafish, resulting in their death before an intestine-specific effect could be observed (Goldsmith and Jobin, unpublished observation). As discussed in a previous section, the development of an oral gavage approach could circumvent this important limitation.

7. Perspectives

Animal models have been used since the inception of medical research. For most models of human disease, the preferred and most utilized animal system of human disease is overwhelmingly the murine system. Despite the tremendous gain of knowledge provided by using murine experimental systems, the long gestation time (18–20 days) and sexual maturation rate (6–8 weeks) combined with high cost of housing and breeding represent significant limitations. Furthermore, experiments with mice are labor intensive and not particularly well suited for high-throughput screening. These limitations have spurred the need to develop other model organisms that could be used to provide initial gene or drug targets information before beginning investigations in more expensive systems.

Transparent, larval zebrafish models have the potential to fill this important niche in the study of human disease, enabling rapid, physiologically relevant in vivo screening. The transparent nature of zebrafish also allows for real-time imaging of pathogenesis, which has already provided key insights into the molecular mechanisms of metastasis [124–127] and tuberculosis dissemination [90–92]. The recent advent of the Casper fish promises to extend the imaging capacity beyond larvae to adult fish, permitting studies in fish with a functional adaptive immune system. The zebrafish has already demonstrated profound bench-to-bedside power, as evidenced by the rapid translation time (~2-years) from the initial reports of the role of H2O2 in neutrophil chemotaxis during wound healing in zebrafish [11] to the first utilizations of such knowledge in human patients [18].

The zebrafish remains a relatively underdeveloped model organism with large amounts of untapped potential. As more is understood about the comparative genome, anatomy, and physiology of zebrafish to that of humans, the relevance and utility of this vertebrate model will only grow and provide a powerful complement to the murine system. Two decades of research has demonstrated the power and relevancy of the zebrafish in modeling human disease. Its unique properties make it an ideal in vivo system for initial use in the interrogation of a given pathology before translating the observations made in the model organism to more expensive murine systems.

References

- 1.Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391(6669):806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuan J, Shaham S, Ledoux S, Ellis HM, Horvitz HR. The C. elegans cell death gene ced-3 encodes a protein similar to mammalian interleukin-1β-converting enzyme. Cell. 1993;75(4):641–652. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90485-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hansson GK, Edfeldt K. Toll to be paid at the gateway to the vessel wall. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2005;25(6):1085–1087. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000168894.43759.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barut BA, Zon LI. Realizing the potential of zebrafish as a model for human disease. Physiological Genomics. 2000;2000(2):49–51. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.2000.2.2.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin JT, Priest JR, Ovcharenko I, et al. Human-zebrafish non-coding conserved elements act in vivo to regulate transcription. Nucleic Acids Research. 2005;33(17):5437–5445. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moens CB, Donn TM, Wolf-Saxon ER, Ma TP. Reverse genetics in zebrafish by TILLING. Briefings in Functional Genomics and Proteomics. 2008;7(6):454–459. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/eln046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White RM, Sessa A, Burke C, et al. Transparent adult zebrafish as a tool for in vivo transplantation analysis. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2(2):183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lieschke GJ, Oates AC, Crowhurst MO, Ward AC, Layton JE. Morphologic and functional characterization of granulocytes and macrophages in embryonic and adult zebrafish. Blood. 2001;98(10):3087–3096. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.10.3087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meeker ND, Trede NS. Immunology and zebrafish: spawning new models of human disease. Developmental and Comparative Immunology. 2008;32(7):745–757. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Novoa B, Figueras A. zebrafish: Model for the Study of Inflammation and the Innate Immune Response to Infectious Diseases: Current Topics in Innate Immunity II. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niethammer P, Grabher C, Look AT, Mitchison TJ. A tissue-scale gradient of hydrogen peroxide mediates rapid wound detection in zebrafish. Nature. 2009;459(7249):996–999. doi: 10.1038/nature08119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raya A, Koth CM, Büscher D, et al. Activation of Notch signaling pathway precedes heart regeneration in zebrafish. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(supplement 1):11889–11895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834204100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathias JR, Perrin BJ, Liu TX, Kanki J, Look AT, Huttenlocher A. Resolution of inflammation by retrograde chemotaxis of neutrophils in transgenic zebrafish. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2006;80(6):1281–1288. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0506346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belousov VV, Fradkov AF, Lukyanov KA, et al. Genetically encoded fluorescent indicator for intracellular hydrogen peroxide. Nature Methods. 2006;3(4):281–286. doi: 10.1038/nmeth866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rieger S, Sagasti A. Hydrogen peroxide promotes injury-induced peripheral sensory axon regeneration in the zebrafish skin. PLoS Biology. 2011;9(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000621. Article ID e1000621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan Q, Qiu WY, Huo YN, Yao YF, Lou MF. Low levels of hydrogen peroxide stimulate corneal epithelial cell adhesion, migration, and wound healing. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2011;52(3):1723–1734. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toth T, Brostrom H, Baverud V, et al. Evaluation of LHP(1% hydrogen peroxide) cream versus petrolatum and untreated controls in open wounds in healthy horses: a randomized, blinded control study. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica. 2011;53:p. 45. doi: 10.1186/1751-0147-53-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiss J, Winkelman FJ, Titone A, Weiss E. Evaluation of hydrogen peroxide as an intraprocedural hemostatic agent in manual dermabrasion. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010;36(10):1601–1603. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poss KD, Wilson LG, Keating MT. Heart regeneration in zebrafish. Science. 2002;298(5601):2188–2190. doi: 10.1126/science.1077857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lien CL, Schebesta M, Makino S, Weber GJ, Keating MT. Gene expression analysis of zebrafish heart regeneration. PLoS Biology. 2006;4(8):p. e260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ng ANY, de Jong-Curtain TA, Mawdsley DJ, et al. Formation of the digestive system in zebrafish: III. Intestinal epithelium morphogenesis. Developmental Biology. 2005;286(1):114–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallace KN, Akhter S, Smith EM, Lorent K, Pack M. Intestinal growth and differentiation in zebrafish. Mechanisms of Development. 2005;122(2):157–173. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.William H, Detrich I, Westerfield M, Zon L. The zebrafish: Cellular and Developmental Biology. New York, NY, USA: Academic Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haramis APG, Hurlstone A, van der Velden Y, et al. Adenomatous polyposis coli-deficient zebrafish are susceptible to digestive tract neoplasia. EMBO Reports. 2006;7(4):444–449. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lam SH, Gong Z. Modeling liver cancer using zebrafish: a comparative oncogenomics approach. Cell Cycle. 2006;5(6):573–577. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.6.2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rekha RD, Amali AA, Her GM, et al. Thioacetamide accelerates steatohepatitis, cirrhosis and HCC by expressing HCV core protein in transgenic zebrafish Danio rerio. Toxicology. 2008;243(1-2):11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park SW, Davison JM, Rhee J, Hruban RH, Maitra A, Leach SD. Oncogenic KRAS induces progenitor cell expansion and malignant transformation in zebrafish. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(7):2080–2090. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fleming A, Jankowski J, Goldsmith P. In vivo analysis of gut function and disease changes in a zebrafish larvae model of inflammatory bowel disease: a feasibility study. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2010;16(7):1162–1172. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oehlers SH, Flores MV, Okuda KS, Hall CJ, Crosier KE, Crosier PS. A chemical enterocolitis model in zebrafish larvae that is dependent on microbiota and responsive to pharmacological agents. Developmental Dynamics. 2011;240(1):288–298. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brugman S, Liu KY, Lindenbergh-Kortleve D, et al. Oxazolone-induced enterocolitis in zebrafish depends on the composition of the intestinal microbiota. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(5):1757–67. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.07.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cinaroglu A, Gao C, Imrie D, Sadler KC. Activating transcription factor 6 plays protective and pathological roles in steatosis due to endoplasmic reticulum stress in zebrafish. Hepatology. 2011;54(2):495–508. doi: 10.1002/hep.24396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amali AA, Rekha RD, Lin CJF, et al. Thioacetamide induced liver damage in zebrafish embryo as a disease model for steatohepatitis. Journal of Biomedical Science. 2006;13(2):225–232. doi: 10.1007/s11373-005-9055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Passeri MJ, Cinaroglu A, Gao C, Sadler KC. Hepatic steatosis in response to acute alcohol exposure in zebrafish requires sterol regulatory element binding protein activation. Hepatology. 2009;49(2):443–452. doi: 10.1002/hep.22667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Groden J, Thliveris A, Samowitz W, et al. Identification and characterization of the familial adenomatous polyposis coli gene. Cell. 1991;66(3):599–600. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kinzler KW, Nilbert MC, Su LK, et al. Identification of FAP locus genes from chromosome 5q21. Science. 1991;253(5020):661–665. doi: 10.1126/science.1651562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Su LK, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, et al. Multiple intestinal neoplasia caused by a mutation in the murine homolog of the APC gene. Science. 1992;256(5057):668–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1350108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2010;60(5):277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bosch FX, Ribes J, Díaz M, Cléries R. Primary liver cancer: worldwide incidence and trends. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(5, supplement 1):S5–S16. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.El-Serag HB, Davila JA, Petersen NJ, McGlynn KA. The continuing increase in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: an update. Annals of internal medicine. 2003;139(10):817–823. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-10-200311180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee MN, Jung EY, Kwun HJ, et al. Hepatitis C virus core protein represses the p21 promoter through inhibition of a TGF-β pathway. Journal of General Virology. 2002;83(9):2145–2151. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-9-2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karrasch T, Jobin C. Wound healing responses at the gastrointestinal epithelium: a close look at novel regulatory factors and investigative approaches. Zeitschrift fur Gastroenterologie. 2009;47(12):1221–1229. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1109766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sartor RB. Microbial influences in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(2):577–594. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sartor RB, Muehlbauer M. Microbial host interactions in IBD: implications for pathogenesis and therapy. Current Gastroenterology Reports. 2007;9(6):497–507. doi: 10.1007/s11894-007-0066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loftus EV. Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(6):1504–1517. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(1):46–54. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pithadia AB, Jain S. Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) Pharmacological Reports. 2011;63(3):629–642. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(11)70575-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saleh M, Elson CO. Experimental inflammatory bowel disease: insights into the host-microbiota dialog. Immunity. 2011;34(3):293–302. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wirtz S, Neufert C, Weigmann B, Neurath MF. Chemically induced mouse models of intestinal inflammation. Nature Protocols. 2007;2(3):541–546. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boirivant M, Fuss IJ, Chu A, Strober W. Oxazolone colitis: a murine model of T helper cell type 2 colitis treatable with antibodies to interleukin 4. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1998;188(10):1929–1939. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.10.1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fichtner-Feigl S, Strober W, Geissler EK, Schlitt HJ. Cytokines mediating the induction of chronic colitis and colitis-associated fibrosis. Mucosal Immunology. 2008;1(supplement 1):S24–S27. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goldsmith JR, Rawls JF, Jobin C. The neuropeptide DALDA protects against NSAID-induced acute intestinal injury in zebrafish larvae. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(5):p. S-474. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaser A, Lee AH, Franke A, et al. XBP1 links ER stress to intestinal inflammation and confers genetic risk for human inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. 2008;134(5):743–756. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaser A, Martínez-Naves E, Blumberg RS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: implications for inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 2010;26(4):318–326. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32833a9ff1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim WR, Brown RS, Terrault NA, El-Serag H. Burden of liver disease in the United States: summary of a workshop. Hepatology. 2002;36(1):227–242. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lazo M, Clark JM. The epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a global perspective. Seminars in Liver Disease. 2008;28(4):339–350. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1091978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Williams R. Global challenges in liver disease. Hepatology. 2006;44(3):521–526. doi: 10.1002/hep.21347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Caldwell SH. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: summary of an AASLD Single Topic Conference. Hepatology. 2003;37(5):1202–1219. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sadler KC, Amsterdam A, Soroka C, Boyer J, Hopkins N. A genetic screen in zebrafish identifies the mutants vps18, nf2 and foie gras as models of liver disease. Development. 2005;132(15):3561–3572. doi: 10.1242/dev.01918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lieber CS. Alcoholic fatty liver: its pathogenesis and mechanism of progression to inflammation and fibrosis. Alcohol. 2004;34(1):9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pham LN, Kanther M, Semova I, Rawls JF. Methods for generating and colonizing gnotobiotic zebrafish. Nature Protocols. 2008;3(12):1862–1875. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Uronis JM, Jobin C. Microbes and colorectal cancer: is there a relationship? Current Oncology. 2009;16(4):22–24. doi: 10.3747/co.v16i4.472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ley RE. Obesity and the human microbiome. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 2010;26(1):5–11. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328333d751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Packey CD, Ciorba MA. Microbial influences on the small intestinal response to radiation injury. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 2010;26(2):88–94. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3283361927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rousseaux C, Thuru X, Gelot A, et al. Lactobacillus acidophilus modulates intestinal pain and induces opioid and cannabinoid receptors. Nature Medicine. 2007;13(1):35–37. doi: 10.1038/nm1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Amaral FA, Sachs D, Costa VV, et al. Commensal microbiota is fundamental for the development of inflammatory pain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(6):2193–2197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711891105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van der Sar AM, Appelmelk BJ, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CMJE, Bitter W. A star with stripes: zebrafish as an infection model. Trends in Microbiology. 2004;12(10):451–457. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kanther M, Rawls JF. Host-microbe interactions in the developing zebrafish. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2010;22(1):10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jault C, Pichon L, Chluba J. Toll-like receptor gene family and TIR-domain adapters in Danio rerio. Molecular Immunology. 2004;40(11):759–771. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oehlers SH, Flores MV, Hall CJ, Swift S, Crosier KE, Crosier PS. The inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) susceptibility genes NOD1 and NOD2 have conserved anti-bacterial roles in zebrafish. Disease Models & Mechanisms. 2011;4(6):832–841. doi: 10.1242/dmm.006122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hall C, Flores MV, Chien A, Davidson A, Crosier K, Crosier P. Transgenic zebrafish reporter lines reveal conserved Toll-like receptor signaling potential in embryonic myeloid leukocytes and adult immune cell lineages. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2009;85(5):751–765. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0708405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fan S, Chen S, Liu Y, et al. Zebrafish TRIF, a Golgi-localized protein, participates in IFN induction and NF-κB activation. Journal of Immunology. 2008;180(8):5373–5383. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Correa RG, Matsui T, Tergaonkar V, Rodriguez-Esteban C, Izpisua-Belmonte JC, Verma IM. Zebrafish IκB kinase 1 negatively regulates NF-κB activity. Current Biology. 2005;15(14):1291–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Correa RG, Tergaonkar V, Ng JK, Dubova I, Izpisua-Belmonte JC, Verma IM. Characterization of NF-κB/IκB proteins in zebra fish and their involvement in notochord development. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2004;24(12):5257–5268. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5257-5268.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2001;1(2):135–145. doi: 10.1038/35100529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Janssens S, Beyaert R. A universal role for MyD88 in TLR/IL-1R-mediated signaling. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2002;27(9):474–482. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02145-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Doyle SE, Vaidya SA, O’Connell R, et al. IRF3 mediates a TLR3/TLR4-specific antiviral gene program. Immunity. 2002;17(3):251–263. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00390-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bates JM, Akerlund J, Mittge E, Guillemin K. Intestinal alkaline phosphatase detoxifies lipopolysaccharide and prevents inflammation in zebrafish in response to the gut microbiota. Cell Host and Microbe. 2007;2(6):371–382. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stockhammer OW, Zakrzewska A, Hegedûs Z, Spaink HP, Meijer AH. Transcriptome profiling and functional analyses of the zebrafish embryonic innate immune response to salmonella infection. Journal of Immunology. 2009;182(9):5641–5653. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hall C, Flores M, Storm T, Crosier K, Crosier P. The zebrafish lysozyme C promoter drives myeloid-specific expression in transgenic fish. BMC Developmental Biology. 2007;7, article 42 doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sepulcre MP, Alcaraz-Pérez F, López-Muñoz A, et al. Evolution of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) recognition and signaling: fish TLR4 does not recognize LPS and negatively regulates NF-κB activation. Journal of Immunology. 2009;182(4):1836–1845. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sullivan C, Charette J, Catchen J, et al. The gene history of zebrafish tlr4a and tlr4b is predictive of their divergent functions. Journal of Immunology. 2009;183(9):5896–5908. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hugot JP, Chamaillard M, Zouali H, et al. Association of NOD2 leucine-rich repeat variants with susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. Nature. 2001;411(6837):599–603. doi: 10.1038/35079107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Eckmann L, Karin M. NOD2 and Crohn’s disease: Loss or gain of function? Immunity. 2005;22(6):661–667. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Noguchi E, Homma Y, Kang X, Netea MG, Ma X. A Crohn’s disease-associated NOD2 mutation suppresses transcription of human IL10 by inhibiting activity of the nuclear ribonucleoprotein hnRNP-A1. Nature Immunology. 2009;10(5):471–479. doi: 10.1038/ni.1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Karrasch T, Jobin C. NF-κB and the intestine: friend or foe? Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2008;14(1):114–124. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kanther M, Sun X, Mhlbauer M, et al. Microbial colonization induces dynamic temporal and spatial patterns of NF-κB activation in the zebrafish digestive tract. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(1):197–207. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dolin PJ, Raviglione MC, Kochi A. Global tuberculosis incidence and mortality during 1990–2000. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1994;72(2):213–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cohn DL, Bustreo F, Raviglione MC. Drug-resistant tuberculosis: review of the worldwide situation and the WHO/IUATLD global surveillance project. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1997;24(supplement 1):S121–S130. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.supplement_1.s121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gandhi NR, Nunn P, Dheda K, et al. Multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis: a threat to global control of tuberculosis. The Lancet. 2010;375(9728):1830–1843. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60410-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Davis JM, Clay H, Lewis JL, Ghori N, Herbomel P, Ramakrishnan L. Real-time visualization of mycobacterium-macrophage interactions leading to initiation of granuloma formation in zebrafish embryos. Immunity. 2002;17(6):693–702. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00475-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Clay H, Davis JM, Beery D, Huttenlocher A, Lyons SE, Ramakrishnan L. Dichotomous role of the macrophage in early mycobacterium marinum infection of the zebrafish. Cell Host and Microbe. 2007;2(1):29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Davis JM, Ramakrishnan L. The role of the granuloma in expansion and dissemination of early tuberculous infection. Cell. 2009;136(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Driever W, Solnica-Krezel L, Schier AF, et al. A genetic screen for mutations affecting embryogenesis in zebrafish. Development. 1996;123:37–46. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Haffter P, Granato M, Brand M, et al. The identification of genes with unique and essential functions in the development of the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Development. 1996;123:1–36. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lieschke GJ, Currie PD. Animal models of human disease: zebrafish swim into view. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2007;8(5):353–367. doi: 10.1038/nrg2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Amsterdam A, Burgess S, Golling G, et al. A large-scale insertional mutagenesis screen in zebrafish. Genes and Development. 1999;13(20):2713–2724. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.20.2713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Amsterdam A, Nissen RM, Sun Z, Swindell EC, Farrington S, Hopkins N. Identification of 315 genes essential for early zebrafish development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(35):12792–12797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403929101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Emery AEH. The muscular dystrophies. The Lancet. 2002;359(9307):687–695. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07815-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Granato M, van Eeden FJM, Schach U, et al. Genes controlling and mediating locomotion behavior of the zebrafish embryo and larva. Development. 1996;123:399–413. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bassett DI, Bryson-Richardson RJ, Daggett DF, Gautier P, Keenan DG, Currie PD. Dystrophin is required for the formation of stable muscle attachments in the zebrafish embryo. Development. 2003;130(23):5851–5860. doi: 10.1242/dev.00799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ong ACM, Wheatley DN. Polycystic kidney disease—the ciliary connection. The Lancet. 2003;361(9359):774–776. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12662-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sun Z, Amsterdam A, Pazour GJ, Cole DG, Miller MS, Hopkins N. A genetic screen in zebrafish indentifies cilia genes as a principal cause of cystic kidney. Development. 2004;131(16):4085–4093. doi: 10.1242/dev.01240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hershberger RE, Morales A, Siegfried JD. Clinical and genetic issues in dilated cardiomyopathy: a review for genetics professionals. Genetics in Medicine. 2010;12(11):655–667. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181f2481f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rakar S, Sinagra G, Di Lenarda A, et al. Epidemiology of dilated cardiomyopathy. A prospective post-mortem study of 5252 necropsies. European Heart Journal. 1997;18(1):117–123. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jiang H, Ge J. Epidemiology and clinical management of cardiomyopathies and heart failure in China. Heart. 2009;95(21):1727–1731. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2008.150177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chen JN, Haffter P, Odenthal J, et al. Mutations affecting the cardiovascular system and other internal organs in zebrafish. Development. 1996;123:293–302. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Stainier DYR, Fouquet B, Chen JN, et al. Mutations affecting the formation and function of the cardiovascular system in the zebrafish embryo. Development. 1996;123:285–292. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sehnert AJ, Huq A, Weinstein BM, Walker C, Fishman M, Stainier DYR. Cardiac troponin T is essential in sarcomere assembly and cardiac contractility. Nature Genetics. 2002;31(1):106–110. doi: 10.1038/ng875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Xu X, Meiler SE, Zhong TP, et al. Cardiomyopathy in zebrafish due to mutation in an alternatively spliced exon of titin. Nature Genetics. 2002;30(2):205–209. doi: 10.1038/ng816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hennekam RCM. Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome: review of the phenotype. American Journal of Medical Genetics A. 2006;140(23):2603–2624. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Koshimizu E, Imamura S, Qi J, et al. Embryonic senescence and laminopathies in a progeroid zebrafish model. PLoS One. 2011;6(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017688. Article ID e17688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Parng C, Seng WL, Semino C, McGrath P. Zebrafish: a preclinical model for drug screening. Assay and Drug Development Technologies. 2002;1(1):41–48. doi: 10.1089/154065802761001293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Weinstein BM, Stemple DL, Driever W, Fishman MC. Gridlock, a localized heritable vascular patterning defect in the zebrafish. Nature Medicine. 1995;1(11):1143–1147. doi: 10.1038/nm1195-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kenny D, Hijazi ZM. Coarctation of the aorta: from fetal life to adulthood. Cardiology Journal. 2011;18(5):487–495. doi: 10.5603/cj.2011.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Fishman MC. gridlock, an HLH gene required for assembly of the aorta in zebrafish. Science. 2000;287(5459):1820–1824. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zhong TP, Childs S, Leu JP, Fishman MC. Gridlock signalling pathway fashions the first embryonic artery. Nature. 2001;414(6860):216–220. doi: 10.1038/35102599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Peterson RT, Shaw SY, Peterson TA, et al. Chemical suppression of a genetic mutation in a zebrafish model of aortic coarctation. Nature Biotechnology. 2004;22(5):595–599. doi: 10.1038/nbt963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hong CC, Peterson QP, Hong JY, Peterson RT. Artery/vein specification is governed by opposing phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase and MAP kinase/ERK signaling. Current Biology. 2006;16(13):1366–1372. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ren B, Deng Y, Mukhopadhyay A, et al. ERK1/2-Akt1 crosstalk regulates arteriogenesis in mice and zebrafish. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2010;120(4):1217–1228. doi: 10.1172/JCI39837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Roden DM. Drug-induced prolongation of the QT interval. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;350(10):1013–1022. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Langheinrich U, Vacun G, Wagner T. Zebrafish embryos express an orthologue of HERG and are sensitive toward a range of QT-prolonging drugs inducing severe arrhythmia. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2003;193(3):370–382. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Milan DJ, Peterson TA, Ruskin JN, Peterson RT, MacRae CA. Drugs that induce repolarization abnormalities cause bradycardia in zebrafish. Circulation. 2003;107(10):1355–1358. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000061912.88753.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Woods IG, Kelly PD, Chu F, et al. A comparative map of the zebrafish genome. Genome Research. 2000;10(12):1903–1914. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.12.1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Etchin J, Kanki JP, Look AT. Zebrafish as a model for the study of human cancer. Methods in Cell Biology. 2011;105:309–337. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381320-6.00013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Lee LMJ, Seftor EA, Bonde G, Cornell RA, Hendrix MJC. The fate of human malignant melanoma cells transplanted into zebrafish embryos: assessment of migration and cell division in the absence of tumor formation. Developmental Dynamics. 2005;233(4):1560–1570. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Stoletov K, Montel V, Lester RD, Gonias SL, Klemke R. High-resolution imaging of the dynamic tumor cell-vascular interface in transparent zebrafish. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(44):17406–17411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703446104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Topczewska JM, Postovit LM, Margaryan NV, et al. Embryonic and tumorigenic pathways converge via Nodal signaling: role in melanoma aggressiveness. Nature Medicine. 2006;12(8):925–932. doi: 10.1038/nm1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]