Abstract

Motivation: Chimeric RNA transcripts are generated by different mechanisms including pre-mRNA trans-splicing, chromosomal translocations and/or gene fusions. It was shown recently that at least some of chimeric transcripts can be translated into functional chimeric proteins.

Results: To gain a better understanding of the design principles underlying chimeric proteins, we have analyzed 7,424 chimeric RNAs from humans. We focused on the specific domains present in these proteins, comparing their permutations with those of known human proteins. Our method uses genomic alignments of the chimeras, identification of the gene–gene junction sites and prediction of the protein domains. We found that chimeras contain complete protein domains significantly more often than in random data sets. Specifically, we show that eight different types of domains are over-represented among all chimeras as well as in those chimeras confirmed by RNA-seq experiments. Moreover, we discovered that some chimeras potentially encode proteins with novel and unique domain combinations. Given the observed prevalence of entire protein domains in chimeras, we predict that certain putative chimeras that lack activation domains may actively compete with their parental proteins, thereby exerting dominant negative effects. More generally, the production of chimeric transcripts enables a combinatorial increase in the number of protein products available, which may disturb the function of parental genes and influence their protein–protein interaction network.

Availability: our scripts are available upon request.

Contact: avalencia@cnio.es

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

The splicing of mRNAs is an essential aspect of eukaryotic gene expression. This process can occur in cis, within a single pre-mRNA, or in trans, between two different pre-mRNAs; in the latter case, chimeric transcripts are generated (Gingeras, 2009). Chimeric transcripts can also be produced by other mechanisms, including gene fusion (Li et al., 2008, 2009), recombination and other mechanisms (Gallei et al., 2004; Gmyl et al., 2003). The defining property of a chimeric RNA transcript is a fusion of transcripts from at least two discrete genes.

The pioneering observations evidencing the joining of sequences from separate genes were made in trypanosomes (Sutton and Boothroyd, 1986), though similar events have been shown to occur in nematodes (Krause and Hirsh, 1987) and higher eukaryotes (Li et al., 2009). More recently, chimeric transcripts were demonstrated also in flies (McManus et al., 2010a, b). In the case of the fly mod gene (mdg4), the independently transcribed pre-mRNAs are formed a chimeric transcript with exons from the sense and anti-sense strands of the mod genomic region. Other genes in fruit fly incorporate both sense and antisense exons, such as lola genes (McManus et al., 2010a, b). In the mosquito, chimeric transcripts were found to involve internal exons from genes at different chromosomal loci (Robertson et al., 2007).

In mammals, chimeric transcripts are frequently associated with cancer (Lackner and Bähler, 2008; Maher et al., 2009a, b). Indeed, abnormal MYC mRNA transcripts, a ubiquitous feature of tumor cells, typically involve one or more exons from another gene spliced to exon 2 of MYC (Chen et al., 2005). Additionally, fusion genes that arise from chromosomal rearrangements have been found in an expressed sequence tag (EST) library (Hahn et al., 2004) and in a more recent study, chimeric proteins were identified in different human cell lines (Frenkel-Morgenstern et al., 2012).

The interesting empirical evidence of human chimeras made up of two genes (Breen and Ashcroft, 1997) was supported in a subsequent study of the human cholesterol acyltransferase-1 (ACAT-1) hybrid mRNA (Li et al., 1999), in which mapped the 5′ Untranslated Region (5′ UTR) of this gene was mapped to Chromosome 7 and the remaining sequence to Chromosome 1 (Li et al., 1999). Paired-end RNA sequencing of human cancer cell lines led to the discovery of tissue specific converging, diverging and overlapping mRNA chimeras (Djebali, 2010; Maher et al., 2009a, b). Finally, high-throughput sequencing of fruit fly mRNAs identified chimeric transcripts with complex genomic architecture (McManus et al., 2010a, b).

Although, a large variety of chimeras have been described at the RNA level, there are still only a few examples in humans, where it has been shown empirically by mass spectrometry experiments that the chimeric RNAs produce corresponding chimeric proteins (Frenkel-Morgenstern et al., 2012). Some examples of chimeric proteins found in tumors, are those that result from recurrent chromosomal translocations, which can be found in different patients with the same tumor type (Mitelman et al., 2005). Although several studies have addressed the potential influence of local sequence features on such recurrence (Aplan, 2006; Mirault et al., 2006; Ortiz de Mendíbil et al., 2009), the design principles of chimeric proteins still remain unclear, for examples the preferential incorporation of a full protein domain from the parental protein.

To better understand the design principles underlying chimeric proteins, here, we present an analysis of a data set of 7,424 human chimeric transcripts (Kim et al., 2006, 2010; Li et al., 2009). Recently, the expression of 175 chimeras in this data set was confirmed by high-throughput RNA sequencing (Frenkel-Morgenstern et al., 2012). We focused on protein domains present in the chimeric transcripts and compared their permutations to those contained in protein coding transcripts generally found in humans. We found that chimeras contain complete protein domains significantly more often than would be expected if gene or exon splicing were assumed to be a random process. Specifically, we show that AT-hook, GTP_EFTU, MHC, SH2, SH3, TyrKc, EF-h domains and WD40 repeats are over-represented among chimeras. Moreover, we discovered that some chimeras potentially encode proteins with novel and unique combinations of domains. Given the observed prevalence of entire protein domains in chimeras, we predict that certain putative chimeras with missing activation domains may actively compete with their parental proteins, thereby exerting dominant negative effects. Interestingly, fusion proteins produced by chromosomal translocations in cancers also incorporate the tyrosine kinase (TyrKc), Runt, AT-hook (DNA binding), NUP repeats (nuclear signals) and coiled coil domains. Therefore, we propose that production of chimeric transcripts may produce active competition with original proteins and produce dominant negative phenotypes in cancer. Finally, it must be noted that chimeras can drive diversification of a given transcriptome offering the opportunity to acquire novel functional proteins.

2 METHODS

2.1 Data sets

The data for chimeric transcripts was taken from ChimerDB (Kim et al., 2006, 2010) and the study of Li et al. (2009). In addition, we used the data set of the chimeric junction sites covered by the RNA-seq reads from a recent study (Frenkel-Morgenstern et al., 2012). Only chimeric transcripts involving two genes were included in our chimera data set, and chimeras with a gap of one or more nucleotides in the junction site were excluded from the analysis. In addition, we separated our chimera data set from known fusion proteins catalogued in dbCRID (Kong et al., 2011), an inventory of fusion proteins produced by chromosomal translocations in human cancers and other diseases. The GENCODE (Harrow et al., 2006) and ENSEMBL (Flicek et al., 2011) databases were used, and to create the ‘all proteins’ data set. To avoid bias in the analysis due to over-representation of identical or similar sequences, we compared the protein sequences using BLAST (Altschul et al., 1997). When sequences were found by BLAST to be similar with an E-value ≤10−3, only one representative was kept in the data set. In addition, short protein coding regions, <100 amino acids, were excluded from the analysis. Domains were defined as in Pfam (Bateman et al., 2004; Finn et al., 2008; Gould et al., 2010) and SMART (Mulder et al., 2005). Finally, for each protein or chimera, we created a list of all possible domain–domain combinations. The basic units in our analysis are these domain pairs.

2.2 Fusion proteins in cancer

We used a data set combined from the study of Ortiz de Mendíbil et al., (2009) and the dbCRID database (Kong et al., 2011), which incorporates fusion sequences of gene-mapped translocation breakpoints in cancer from the Mitelman Database of Chromosome Aberrations in Cancer (Mitelman et al., 2005). Sequences of fusion transcripts shorter than 100 amino acids were excluded from the analysis and thus, we analyzed a total of 323 gene fusions in which both partner genes contributed an annotated protein domain to the chimeric fusion protein generated by the translocation. Most these fusions (>60%) were reported in hematological tumors.

2.3 Random data sets and the null model

A random chimera data set was generated by randomly mixing and matching known protein coding sequences to create ‘artificial’ chimeric transcripts, and a set of 10,000 of these random chimeras was used in the analysis. To test if the chimeras incorporate full protein domains, the null hypothesis was that frequencies of full domains in the ‘real’ and randomly generated chimeras are similar when these sets are compared. We used a null hypothesis to test if certain domains are enriched in the chimeras and if they produce unique combinations of domains, i.e. whether the frequency of the domains is equivalent in the chimeras and in all human proteins when all the chimeras are compared with all proteins.

2.4 Enrichment of the protein domains

To verify the functionality of protein domains, The Eukaryotic Linear Motifs resource (ELM; Gould et al., 2010) was used. To recognize potential membrane proteins participating in a given chimera, we used TargetP (Emanuelsson et al., 2007) and ELM (Gould et al., 2010). The 20-top domain frequencies in chimeras were considered for the over-representation analysis of specific domains versus the domain frequencies in all the human proteins. The standard error was calculated using the distributions of the domain frequencies in chimeras and all proteins as follows:

| (1) |

where N equals 20 (top domains) and STDEV was calculated as a standard deviation of the absolute differences between the observed and expected frequencies of 20-top domains.

An expected frequency for every domain was calculated using an assumption that a domain can be owned from any of two parental proteins and it calculated by the formula:

|

(2) |

where PALLPRTs (domain) is the observed frequency of the domain in a data set of all human proteins. The domains were considered as over-represented in the chimeras if their frequencies were at least two standard errors bigger than the corresponding frequencies in all human proteins. The 20 most common (20-top) domains were chosen for the analysis because all the other domains had a frequency of <1% (Supplementary Material). These 20-top corresponded to 69% of the domains identified in all proteins, and 61% of those in all the chimeras.

2.5 Annotation of chimeras

The sequence similarities between the chimeric RNA transcripts and human-genomic regions were identified using in-house software and the UCSC BLAT search (Kent, 2002) to annotate the genes participating in each chimera. Using information on known transcripts from ENSEMBL (Flicek et al., 2011) and an in-house Perl program, the aligned exons, introns and untranslated regions in the chimeras were recognized. NCBI BLAST (Altschul et al., 1997) was applied to delineate the parental protein domains corresponding to the genomic regions contained within each chimeric mRNA. All the domain annotation results were manually inspected. Finally, WU BLAST (Lopez et al., 2003) was employed to define more precisely short or ‘strange’ genomic regions, as WU BLAST has proven most efficient when transcript composition is unknown (Elizabeth Cha and Rouchka, 2005).

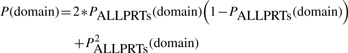

2.6 Analysis of chimeric proteins translated in frame

To identify possible in frame translations of a given chimera, we translated all the chimera transcripts in six frames. We ran UCSC BLAT search (Kent, 2002) and NCBI BLAST (Altschul et al., 1997) and used ENSEMBL (Flicek et al., 2011) to identify a frame enabled correct translation of exons from both proteins participating in chimeras. Thus, only the exons of two parental genes, appearing in the sequence of ESTs, were used for the domain analysis of the chimeras (Fig. 1). In our chimera data set, 1,643 chimeras had a correct frame for two parental proteins that ensured a directed translation without a stop codon at the junction site of chimeras. We analyzed this collection separately and found an over-representation of protein domains, as in the whole chimera data set.

Fig. 1.

A schematic representation of the chimera of TUFT1 and RNF115. This chimera is supported by two distinct ESTs (ESTid1 = ‘CB137847.1’ and ESTid2 = ‘CB137162.1’). The corresponding exon of TUFT1 incorporated in the chimera is depicted in blue and the exons of RNF115 are in brown

2.7 Comparison of domain pairs

We carried out a paired Wilcoxon test for each collection of protein sequences (Fay and Proschan, 2010), comparing the differences in the permutations of protein domains within the domain pairs of all the chimeras with that of all the human proteins, and that of all the chimeras against the random chimeras. The average length of a specific domain was computed considering all the proteins predicted to have this domain.

3 RESULTS

We surveyed all the functional domains in proteins encoded by chimeric transcripts translated and we found that 27% of chimeras tend to contain complete functional domains of their proteins, significantly higher than in the corresponding random data set of chimeras (Wilcoxon test, P < 10E−21). We noted that chimeras contain various well-characterized complete protein domains (Supplementary Material), representing most protein domains (69%) of those present in the GENECODE 3C (human) database (Table 1). Remarkably, we found that the chimeras in our data set were significantly enriched in AT_hook, GTP_EFTU, MHC, SH2, SH3, TyrKc, EF-h domains and WD40 (see ‘Results’ section below). These findings complement our earlier discovery of enrichment in transmembrane domains among chimeras (Frenkel-Morgenstern et al., 2012). Moreover, we found that that 30.2% of chimeras confirmed by RNA-seq reads in the study of (Frenkel-Morgenstern et al. 2012) encode complete protein domains. Most of the chimeras are weakly expressed transcripts and they are very tissue-specific (Frenkel-Morgenstern et al., 2012). Given the prevalence of entire protein domains in chimeras, we suggest that certain chimeras may actively compete with the wild-type parental proteins, especially transcription factors.

Table 1.

The enriched protein domains in chimeras

| Chimeric data set | All human genesa | All chimerasb | All chimeras confirmed by RNA-seq readsc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total genes | 22 304 | 7424 | 175 |

| Identified domainsd | 18 045 | 1318 | 55 |

| ANK | 1.9% | 2% | 0% |

| AT_hook | 0.2% | 1.6% | 0% |

| Coiled Coil | 18.1% | 18.6% | 10% |

| EFhe | 1.1% | 3.9% | 2% |

| EGF-like | 5.5% | 3.2% | 2% |

| GTP_EFTU | 0.5% | 1.9% | 4% |

| HOX | 1.5% | 1.2% | 0% |

| IG-like | 7.2% | 4.4% | 2% |

| LRR | 7% | 3% | 0% |

| MHC | 0.3% | 1.8% | 4% |

| PHD | 0.8% | 1.9% | 0% |

| Pkinase | 4% | 2.2% | 0% |

| RING | 2.4% | 1.9% | 0% |

| RRM | 1.6% | 2.2% | 6% |

| Runt | 0% | 1.2% | 0% |

| SH2 | 0.8% | 2.5% | 2% |

| SH3 | 2% | 3.5% | 2% |

| TyrKc | 0.7% | 2.5% | 0% |

| WD40f | 2.3% | 5.5% | 8% |

| ZnF | 8% | 8% | 6% |

| P-valueg | 10E−5 |

aAll human genes from GENCODE (Harrow et al., 2006).

bAll ESTs and mRNAs from the ChimerDB collection (Kim et al., 2010), 200 transcripts of human data set (Li et al., 2009).

cAll chimeric transcripts confirmed by RNA-seq from all three aforementioned data sets (Frenkel-Morgenstern et al., submitted for publication).

dThe additional 3701 transmembrane domains and 2339 signal peptides were identified for the same data set of all chimeras (Frenkel-Morgenstern et al., 2012). For all chimeras confirmed by RNA-seq reads, the additional overrepresented domains are: ACTIN (4%), ATP_synt_A (13%) and Ribosomal (11%).

e10% of proteins having multiple EFh domains incorporate them from both of the parental proteins.

fA number of WD40 repeats in chimeras is on average 1.3 in comparison to 6.1 in the parental proteins.

gP-value was calculated by the Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test using percentage values for the appearance of different domains in chimeras and in all human genes.

3.1 Domains from membrane proteins and receptors in chimeras

The domains of membrane proteins and receptors, namely, MHC and receptor tyrosine kinases catalytic domain (TyrKc) are enriched in chimeras (P < 10E−5). Moreover, we noted that short coiled-coil domains (<50 aa) are also significantly enriched in human chimeras, likely reflecting the enrichment of parental membrane proteins (Barr and Short, 2003; De Matteis and Morrow, 2000; Short et al., 2005). These findings extend our previous observations that chimeras incorporate transmembrane domains and signal peptides to change a cellular localization of parental proteins (Frenkel-Morgenstern et al., 2012). Notably, 15% of chimeras confirmed by RNA-seq reads (Frenkel-Morgenstern et al., 2012) indeed incorporate coiled-coil and MHC domains of the parental membrane proteins (Table 1).

3.2 EF-hand domains in chimeras

The ‘EF-hand’ (EFh) domain name is the Calcium (Ca)-binding variant of a helix–loop–helix motif discovered in the structure of parvalbumin, a small Ca-binding protein isolated from carp muscle (Kretsinger and Nockolds, 1973). Subsequently, many other Ca-binding proteins have been identified (Kawasaki and Kretsinger, 1994, 1995). To date, there are >3000 EFh-related entries in the NCBI Reference Sequences Data Bank (Grabarek, 2006). Typically, the role of proteins containing EFh motifs is to ‘translate’ a regulatory signal into various functional responses (Grabarek, 2006). EFh motifs always occur in pairs, forming an EFh domain.

We found a significant enrichment of EFh domains among the chimeras in our data sets (P < 10E−5). We noted that chimeras had more than one EFh domain, with 20% having three or four domains, supporting the premise that they are functional. Remarkably, some chimeras incorporate Ca-binding domains from each of the parental proteins, and thus, they have multiple EFh domains (Table 1).

3.3 WD40 repeats in chimeras

WD40 repeats of about 40 amino acid residues are found in a wide variety of eukaryotic proteins (Andrade et al., 2000). WD40 proteins play roles as adaptor and regulatory modules in various processes including signal transduction, pre-mRNA processing, transcriptional activation, cytoskeleton assembly and cell cycle regulation (Andrade et al., 2000). WD40 repeats form β-propeller structures, which act as a platform for stable association between proteins. Additionally, the WD40 repeat propeller structure is an adaptable module that can recognize particular post-translational modifications (Stirnimann et al., 2010; Xu and Min, 2011).

We found a significant enrichment of WD40 repeats in chimeras (P-value < 10E−5). In particular, 9% of chimeras confirmed by RNA-seq reads at the chimeric junction site incorporate WD40 repeats (Table 1). However, it is notable that the number of repeats in chimeras is on average 1.3, as opposed to 6.1 in the parental proteins (Table 1). This reduction in the number of repeats raises the possibility that these domains are only partially folded and may be non-functional, and thus, they may contribute to dominant negative effects (see below) if they are fused into transcription factors.

3.4 DNA and GTP binding domains in chimeras

AT hooks are type of DNA-binding motifs with a preference for A/T rich regions and found in the high mobility group (HMG) proteins (Reeves and Beckerbauer, 2001) and others (Singh et al., 2006). Among other functions, HMG proteins are also involved in the transcription regulation of genes containing, or in close proximity to, AT-rich regions. The AT hooks domains are enriched in chimeras (Wilcoxon test, P < 10E−5) and incorporate with other functional domains, which may influence the activity of parental proteins especially transcription factors incorporated in chimeras.

Zinc finger proteins (ZFPs) are a category of DNA-binding proteins that bind to DNA and RNA and other proteins through a ‘finger-shaped’ fold stabilized by zinc ions (Brown, 2005; Dhanasekaran et al., 2006; Hall, 2005; Johnston et al., 2006; Negi et al., 2008). In most organisms, ZFPs are located in the cell nucleus, where they regulate the activity of genes by binding to target nucleotide sequences. Each zinc finger domain (ZFD) consists of 30 amino acids, which fold into a ββα-structure, in which the Zn ion stabilizes the conserved Cys2His2 or other residues (Brown, 2005; Dhanasekaran et al., 2006; Hall, 2005; Johnston et al., 2006; Negi et al., 2008). The target DNA-binding site for ZFDs primarily comprises a specific three nucleotide sequence (Grover et al., 2010).

Interestingly, our analyses predicted all different types of ZFDs to be represented among chimeras: ZnF_A20, ZnF_C2C2, ZnF_C2H2, ZnF_C2HC, ZnF_C3H1, ZnF_C4, ZnF_CDGSH, ZnF_RBZ, ZnF_TAZ and ZnF_ZZ. Moreover, we noted that 8% of human chimeras incorporate parental proteins that themselves possess more than one type of ZFD (Table 1). Accordingly, chimeras were found to typically contain up to five ZFDs, and have more ZFDs ‘repeats’ on average relative to all human proteins, 2.1 versus 1.03 ZFDs, respectively. It has been speculated that a number of ZFDs in tandem recognize longer DNA sequences (Alwin et al., 2005; Beerli and Barbas, 2002; Beerli et al., 2000; Kim and Pabo, 1998; Liu et al., 1997; Pabo et al., 2001). Moreover, we found that transcription activators or repressors were highly represented among ZF proteins in chimeras (19.5%, P-value < 6.5E−4). Taken together with the aforementioned multiplicity of ZFDs in chimeras, these findings suggest that chimeric zinc finger transcription activators and zinc finger transcription repressors potentially recognize longer DNA sequences.

3.5 Novel combinations of protein domains in chimeras

We compared the permutations of domain pairs in chimeras versus those in all proteins. We found that most domain pair combinations are represented in chimeras but also noted novel domain pairs, including HLH (Helix–Loop–Helix) and Pfam:GTP_EFTU (GTP-binding domain) as well as Pfam:Hydrolase_3 domain and Pfam:Polyprenyl_synt, coiled_coil domain and ZnF_C2C2 and others (Table 2). Notably, the domains participating in a novel domain combination in a given chimera were found in multiple ESTs from the two parental proteins (Table 2). Moreover, the same order and amount of exons are incorporated in the chimera as found in both parental proteins. Expression of the novel chimeras was confirmed at the RNA level by RNA-seq reads, with 4.1 chimeric reads on average in different human tissues (Frenkel-Morgenstern et al., 2012). These observations support the premise that there are specific design principles underlying the formation of chimeras.

Table 2.

The novel domain combinations found in chimeras

| Domain 1 | Domain 2 | Chimeric ESTs | Gene 1 | Gene 2 | Potential function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VHS (membrane targeting/cargo recognition role in vesicular trafficking) | BRIX (ribosomal RNA processing) | AW977393 | GGA2 (ADP-ribosylation factor binding protein 2) | GNG5 (RNA processing factor 1) | Golgi-trafficking |

| HLH (DNA-binding) | Pfam:GTP_EFTU (GTP binding domain) | BE514178 BC002845 BE397892 | TCF3 (transcription factor E2-alpha) | EEF1A1 (Eukaryotic Translation Elongation Factor 1 Alpha) | Dominant negative |

| Pfam:Pkinase (kinase catalytic domain) | Pfam:ubiquitin (ubiquitin, location or trafficking of the protein) | BF349450 | UBD (ubiquitin D) | CSNK1D (casein kinase 1, delta isoform 1) | Change localization or trafficking |

| Pfam:Hydrolase_3 | Pfam:Polyprenyl_synt | BG491331 BM555536 BM809442 | PMM2 (phosphomannomutase 2) | FDPS (farnesyl diphosphate synthase isoform a) | Dominant negative |

| ZnF_C2C2 | Coiled-coil (DNA binding) domain | BG164187 | Prickle-like 2 (Drosophila homolog) | TCEA3 (transcription elongation factor A (SII), 3) | Dominant negative |

| PHD-zinc finger | Coiled-coil (DNA binding) domain | AB032253 | BAZ1B (bromodomain adjacent to zinc finger domain, 1B), transcription factor | GRID1 (Glutamate receptor delta-1 subunit) | Dominant negative |

| PHD-zinc finger | Coiled-coil (DNA binding) domain | DA092156 | PHF14 (PHD finger protein 14 isoform 1) uncharacterized protein | DC344466 Unknown protein | Unknown |

Every domain combination is confirmed by the putative chimeric ESTs from our data set. Potential function of the resulting chimera is proposed.

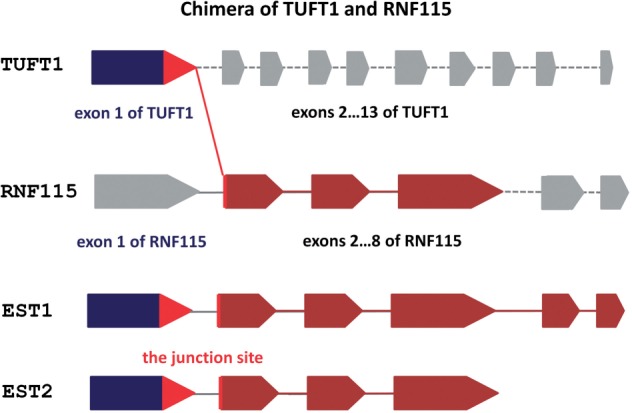

3.6 Dominant negative effects

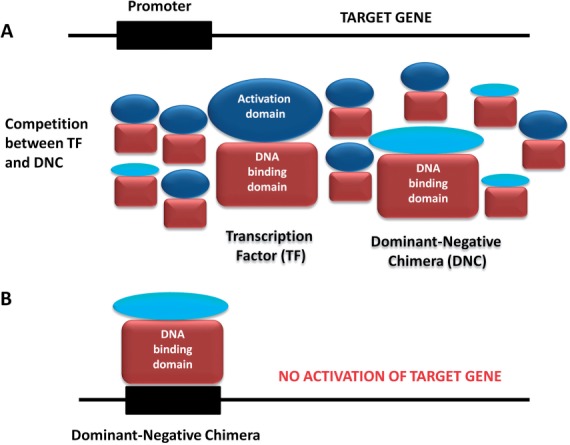

Mutated transcription factors and mutated proteins that function as dimers/multimers have the potential to exert dominant negative effects competing with the parental proteins (Fig. 2). Namely, if a mutated protein has lost a particular activity but is still able to form a multimer or bind DNA, it can antagonize the function of the wild-type protein (Maki et al., 2008). Given the prevalence in our chimera data set of entire DNA-binding domains in the absence of transcriptional activation domains, we suspect that such chimeras compete with the parental transcription factors, thus exerting dominant negative effects (Fig. 2). In support of our hypothesis, a chimera that comprises a ligand-dependent transcriptional factor, the Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma-2 (PPARG2) and the amino-terminal domain of the nuclear receptor co-repressor (CoR) has already been shown to exert a dominant negative effect (Suzuki et al., 2010).

Fig. 2.

A schematic representation of the competition mechanism between the wild-type transcription factor (TF) and the dominant-negative chimera (DNC). (A). A lowly expressed DNC compete with TF. (B). As a result of the competition, the DNC binds a promoter region but cannot activate a target gene inserting dominant- negative effect.

Based on our hypothesis, we predict that a chimera from our data set, comprising the E2-α transcription factor, TCF3 (Immunoglobulin enhancer-binding factor E12/E47) and the Ribosomal protein, RPS19 (EST = ‘BC009346.1’) exerts dominant negative effects. Although the full sequence of RPS19 is present, encoding a known transcriptional repressor that is located in the cytoplasm and nucleus, and that can form homodimers and heterodimers (Fig. 3A), only the DNA-binding domain of the nuclear transcription factor TCF3 is incorporated in the chimera, the activation domain of TCF3 is missing (Fig. 3A). Therefore, the resulting chimera can potentially bind TCF3's target DNA but it cannot activate transcription and accordingly it could compete with wild-type TCF3 to bind DNA (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Putative chimeric proteins can exert dominant negative effects. (A) Schematic view of transcription factor (TCF3) and ribosomal protein (RPS19). (B) The putative chimeric protein harnesses RPS19 to the DNA-binding domain of TCF3 and likely exerts a dominant negative effect by competing with wild type TCF3 for DNA binding. (C) Schematic view of guanine-monophosphate-synthetase (GMPS), which functions as a homodimer, and mixed-lineage leukemia (MLL). (D) The putative chimeric MLL/GMPS protein lacking a functional GMPS domain likely competes with parental GMPS to form dysfunctional heterodimers, impairing the biosynthesis regulated by GMPS

Overall, around 14% of the chimeras in our data set have the potential to exert dominant negative effects. We also noted changes in the permutations of domain pairs among chimeras, particularly when considering domains found in enzymes that function as dimers. This finding suggests that such chimeric enzymes could exert dominant negative effects, but when considering enzymes, it is important to note that the final phenotype would be strongly dependent on the expression level of the chimeric protein. For example, in the human data set (Li et al., 2009), a translocation between the myeloid/lymphoid or mixed-lineage leukemia (MLL) protein and guanine monophosphate synthetase (GMPS) produces a chimera with potential to exert dominant negative effects. Typically, MLL positively regulates the expression of target genes, including multiple HOX genes (Li et al., 2005), but some MLL gene fusions have been shown to exert dominant effects (Li et al., 2005). GMPS is an enzyme that functions as a homodimer, and although the functional domain is missing in the chimera, the dimerization domain is preserved along with the Zinc finger and PHD domains (Fig. 3C). Therefore, the resulting chimeric enzyme can potentially dimerize with the wild-type functional GMPS enzyme but interfere with its function due to the non-functional part of MLL (Fig. 3D), and thus exert a dominant negative effect. Similarly, the AML1/EVI-1 chimera generated by translocation has been shown to exert dominant negative effects (Mitani, 2004) and the MLL/AF4 fusion product has been suggested to function as a dominant negative protein (Domer et al., 1993).

We focused our analysis on chimeras that incorporate parts of transcription factors (activators or repressors) as it has been shown that even low expression of mutated transcription factors can interfere with gene activation/repression. The abundance of chimeras containing transcription factor among DNA-binding proteins was determined to be (19.5%, P < 6.5E−6). Given the prevalence of entire protein domains in chimeras, we predict that even low expressed chimeras that incorporate the DNA-binding domains of transcription factors but have lost activation domains actively compete with the parental proteins, thus exerting dominant negative effects.

3.7 Protein domains in cancer fusion proteins

Using the same prediction procedures, we identified the main classes of fusion proteins resulting from translocations: the tyrosine kinase (TyrKc) domains (5.7%), the Runt domain (4.5%), the AT-hook DNA-binding domains (4.8%), the NUP repeats (6%) and coiled-coil domains (18.5%). Interestingly, most of these domains are DNA-binding domains or they incorporate nuclear signals. Our findings indicate that only certain combinations of protein domains are present in fusion proteins, forming non-random domain combinations, and implying that such combinations are subject to potential functional constraints (Ortiz de Mendíbil et al., 2009). As mentioned above, the signature of DNA-binding domains and transcription factors can produce dominant negative phenotypes (Fig. 3A and B).

4 DISCUSSION

Here, we show that chimeras are particularly enriched in eight types of protein domains. In conjunction with our earlier study, our data raise the possibility that chimeras result not only in altered cellular localizations due to a sizable enrichment in transmembrane domains (Frenkel-Morgenstern et al., submitted for publication), but also in the acquisition of a number of other new functions.

Using the ELM resource, the position and length of each domain within a given protein was assigned and annotated. Thus, the domain composition and domain order relative to the protein sequence was readily available for each protein, allowing us to identify unique and novel domain combinations in chimeras. Of note, as many chimeras have been evidenced by multiple ESTs (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Material), we propose that some chimeras may be produced by regulated trans-splicing and have functional advantages. Elucidating the possible trans-splicing mechanisms, in humans, remains as a promising field of research.

In this study, we focused on chimeras ‘in-frame’ and chimeras confirmed by RNA sequencing experiments (Frenkel-Morgenstern et al., 2012). For all chimeras confirmed by RNA-seq and ‘in-frame’, we predicted the protein domains they contained and compared the permutations of domain pairs to those found in all proteins or in random data sets. Using this approach, we identified novel domain pairs that are unique to chimeras, which incorporate transcription factors as parental genes. Given the fact that even low expression of mutated transcription factors can interfere with the function of the wild-type transcription factor, we propose that many chimeras exert dominant negative phenotypes. Taking into consideration the protein domains identified in the fusion proteins, we propose that dominant negative effects of fusion proteins may be frequent in cancer. Moreover, chimeras may influence the protein–protein interactions of parental genes in the protein interaction network. Thus, chimeras with domains from the highly connected proteins will produce more consequences than chimeras from less connected proteins. Taking in consideration, the recent findings on the highly expressed genes incorporated in the human chimeras (Frenkel-Morgenstern et al., 2012), and the fact that highly expressed genes tend to have more protein–protein interaction partners (Krylov et al., 2003), we propose that chimeras can influence the protein–protein interaction network of the parental genes.

Having validated the existence of chimeric proteins in eukaryotes, we stress the need to take chimeric proteins into consideration when carrying out experimental studies of protein cellular localization. Moreover, the potential dominant negative effect of chimeras should be taken into account when protein–protein interactions are studied. Finally, we suggest that future studies investigate if chimeric RNAs represent useful biomarkers for the early diagnosis of different different cancers.

Supplementary Material

5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr Miguel Vazquez for help with random data sets, Jose Manuel Rodriguez for the ELM, SignalP and TargetP scripts and Dr Dan Michaeli for valuable discussions. The authors also thank Prof. Sanghyuk Lee and Prof. Seokmin Shin for making available the chimeric transcripts in the ChimerDB databases.

Funding: Spanish Government grant (CONSOLIDER, CSD2007-00050), BI02007-666855, Open PHACTS (IMI-115191-2) and the NHGRI-NIH ENCODE grant (HG00455-04). Miguel Servet (FIS) to M.F.-M.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Altschul S., et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alwin S., et al. Custom zinc-finger nucleases for use in human cells. Mol. Ther. 2005;12:610–617. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.06.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade M.A., et al. Homology-based method for identification of protein repeats using statistical significance estimates. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;298:521–537. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aplan P.D. Chromosomal translocations involving the MLL gene: molecular mechanisms. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:1265–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr F.A., Short B. Golgins in the structure and dynamics of the Golgi apparatus. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2003;15:405–413. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A., et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D138–D141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerli R.R., Barbas C.F. Engineering polydactyl zinc-finger transcription factors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:135–141. doi: 10.1038/nbt0202-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerli R.R., Dreier B., Barbas C.F. Positive and negative regulation of endogenous genes by designed transcription factors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:1495–1500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040552697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen M.A., Ashcroft S.J. A truncated isoform of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II expressed in human islets of Langerhans may result from trans-splicing. FEBS Lett. 1997;409:375–379. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00555-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R.S. Zinc finger proteins: getting a grip on RNA. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2005;15:94–98. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., et al. High frequency trans-splicing in a cell line producing spliced and polyadenylated RNA polymerase I transcripts from an rDNA-myc chimeric gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:2332–2342. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Matteis M.A., Morrow J.S. Spectrin tethers and mesh in the biosynthetic pathway. J. Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 13):2331–2343. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.13.2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanasekaran M., Negi S., Sugiura Y. Designer zinc finger proteins: tools for creating artificial DNA-binding functional proteins. Acc. Chem. Res. 2006;39:45–52. doi: 10.1021/ar050158u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djebali S., et al. Evidence for transcript networks composed of chimeric RNAs in human cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(1):e28213. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domer P.H., et al. Acute mixed-lineage leukemia t(4;11)(q21;q23) generates an MLL-AF4 fusion product. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:7884–7888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elizabeth Cha,I., Rouchka E.C. Comparison of current BLAST software on nucleotide sequences. IPDPS. 2005;19:8. doi: 10.1109/IPDPS.2005.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuelsson O., et al. Locating proteins in the cell using TargetP, SignalP and related tools. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:953–971. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay M.P., Proschan M.A. Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney or t-test? On assumptions for hypothesis tests and multiple interpretations of decision rules. Stat. Surv. 2010;4:1–39. doi: 10.1214/09-SS051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn R.D., et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D281–D288. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flicek P., et al. Ensembl 2011. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D800–D806. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel-Morgenstern, et al. Chimeras taking shape: Potential function of proteins encoded by chimeric RNA transcripts. 2012 doi: 10.1101/gr.130062.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallei A., et al. RNA recombination in vivo in the absence of viral replication. J. Virol. 2004;78:6271–6281. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6271-6281.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingeras T.R. Implications of chimaeric non-co-linear transcripts. Nature. 2009;461:206–211. doi: 10.1038/nature08452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gmyl A.P., et al. Nonreplicative homologous RNA recombination: promiscuous joining of RNA pieces? RNA. 2003;9:1221–1231. doi: 10.1261/rna.5111803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould C.M., et al. ELM: the status of the 2010 eukaryotic linear motif resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D167–D180. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabarek Z. Structural basis for diversity of the EF-hand calcium-binding proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;359:509–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover A., et al. Re-programming DNA-binding specificity in zinc finger proteins for targeting unique address in a genome. Syst. Synth. Biol. 2010;4:323–329. doi: 10.1007/s11693-011-9077-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn Y., et al. Finding fusion genes resulting from chromosome rearrangement by analyzing the expressed sequence databases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:13257–13261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405490101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall T.M. Multiple modes of RNA recognition by zinc finger proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2005;15:367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrow J., et al. GENCODE: producing a reference annotation for ENCODE. Genome Biol. 2006;7(Suppl. 1):S4.1–S4.9. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-s1-s4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston R.J., Jr., et al. An unusual Zn-finger/FH2 domain protein controls a left/right asymmetric neuronal fate decision in C. elegans. Development. 2006;133:3317–3328. doi: 10.1242/dev.02494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H., Kretsinger R.H. Calcium-binding proteins. 1: EF-hands. Protein Profile. 1994;1:343–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H., Kretsinger R.H. Calcium-binding proteins 1: EF-hands. Protein Profile. 1995;2:297–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent W.J. BLAT: the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 2002;12:656–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.S., Pabo C.O. Getting a handhold on DNA: design of poly-zinc finger proteins with femtomolar dissociation constants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:2812–2817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim N., et al. ChimerDB: a knowledgebase for fusion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D21–D24. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim P., et al. ChimerDB 2.0: a knowledgebase for fusion genes updated. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D81–D85. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong F., et al. dbCRID: a database of chromosomal rearrangements in human diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D895–D900. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause M., Hirsh D. A trans-spliced leader sequence on actin mRNA in C. elegans. Cell. 1987;49:753–761. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90613-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretsinger R.H., Nockolds C.E. Carp muscle calcium-binding protein. II. Structure determination and general description. J. Biol. Chem. 1973;248:3313–3326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krylov D.M., et al. Gene loss, protein sequence divergence, gene dispensability, expression level, and interactivity are correlated in eukaryotic evolution. Genome Res. 2003;13:2229–2235. doi: 10.1101/gr.1589103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackner D., Bähler J. Translational control of gene expression from transcripts to transcriptomes. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2008;271:199–251. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(08)01205-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B.L., et al. Human acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase-1 (ACAT-1) gene organization and evidence that the 4.3-kilobase ACAT-1 mRNA is produced from two different chromosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:11060–11071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.11060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., et al. A neoplastic gene fusion mimics trans-splicing of RNAs in normal human cells. Science. 2008;321:1357–1361. doi: 10.1126/science.1156725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., et al. Gene fusions and RNA trans-splicing in normal and neoplastic human cells. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:218–222. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.2.7358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., et al. Short homologous sequences are strongly associated with the generation of chimeric RNAs in eukaryotes. J. Mol. Evol. 2009;68:56–65. doi: 10.1007/s00239-008-9187-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.Y., Liu D.P., Liang C.C. New insight into the molecular mechanisms of MLL-associated leukemia. Leukemia. 2005;19:183–190. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., et al. Design of polydactyl zinc-finger proteins for unique addressing within complex genomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:5525–5530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez R., et al. WU-Blast2 server at the European Bioinformatics Institute. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3795–3798. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher C.A., et al. Transcriptome sequencing to detect gene fusions in cancer. Nature. 2009a;458:97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature07638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher C.A., et al. Chimeric transcript discovery by paired-end transcriptome sequencing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009b;106:12353–12358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904720106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki K., Yamagata T., Mitani K. Role of the RUNX1-EVI1 fusion gene in leukemogenesis. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:1878–1883. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00956.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus C.J., et al. Regulatory divergence in Drosophila revealed by mRNA-seq. Genome Res. 2010a;20:816–825. doi: 10.1101/gr.102491.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus C.J., et al. Global analysis of trans-splicing in Drosophila. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010b;107:12975–12979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007586107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirault M.E., Boucher P., Tremblay A. Nucleotide-resolution mapping of topoisomerase-mediated and apoptotic DNA strand scissions at or near an MLL translocation hotspot. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;79:779–791. doi: 10.1086/507791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitani K. Molecular mechanisms of leukemogenesis by AML1/EVI-1. Oncogene. 2004;23:4263–4269. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitelman F., Mertens F., Johansson B. Prevalence estimates of recurrent balanced cytogenetic aberrations and gene fusions in unselected patients with neoplastic disorders. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2005;43:350–366. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder N.J., et al. InterPro, progress and status in 2005. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D201–D205. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negi S., et al. New redesigned zinc-finger proteins: design strategy and its application. Chemistry. 2008;14:3236–3249. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz de Mendíbil I., Vizmanos J.L., Novo F.J. Signatures of selection in fusion transcripts resulting from chromosomal translocations in human cancer. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabo C.O., Peisach E., Grant R.A. Design and selection of novel Cys2His2 zinc finger proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2001;70:313–340. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves R., Beckerbauer L. HMGI/Y proteins: flexible regulators of transcription and chromatin structure. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1519:13–29. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(01)00215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson H.M., et al. The bursicon gene in mosquitoes: an unusual example of mRNA trans-splicing. Genetics. 2007;176:1351–1353. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.070938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short B., Haas A., Barr F.A. Golgins and GTPases, giving identity and structure to the Golgi apparatus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1744:383–395. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M., D'Silva L., Holak T.A. DNA-binding properties of the recombinant high-mobility-group-like AT-hook-containing region from human BRG1 protein. Biol. Chem. 2006;387:1469–1478. doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirnimann C.U., et al. WD40 proteins propel cellular networks. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2010;35:565–574. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton R.E., Boothroyd J.C. Evidence for trans splicing in trypanosomes. Cell. 1986;47:527–535. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90617-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S., et al. The role of the amino-terminal domain in the interaction of unliganded peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma-2 with nuclear receptor co-repressor. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2010;45:133–145. doi: 10.1677/JME-10-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C., Min J. Structure and function of WD40 domain proteins. Protein Cell. 2011;2:202–214. doi: 10.1007/s13238-011-1018-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.