Abstract

Mycobacterial growth in liquid culture can go undetected by automated, nonradiometric growth detection systems. In our laboratory, instrument-negative tubes from the Bactec MGIT 960 system are inspected visually for clumps suggestive of mycobacterial growth, which (if present) are examined by acid-fast smear analysis. A 3-year review demonstrated that ∼1% of instrument-negative MGIT cultures contained mycobacterial growth and that 10% of all cultures yielding mycobacteria were instrument negative. Isolates from instrument-negative MGIT cultures included both tuberculous and nontuberculous mycobacteria.

TEXT

Mycobacteria remain an important cause of infectious diseases in developing and developed countries alike. Although amplified molecular methods are making inroads as diagnostic tools, culture-based methods are still heavily relied upon. Owing to the challenges of cultivating mycobacteria, use of at least two culture media (one liquid, one solid) is recommended to maximize recovery of clinical isolates (4, 10).

Until recently, liquid broth mycobacterial culture involved a radiometric growth detection method. Many clinical laboratories, including our own, have adopted nonradiometric detection methods, which offer several quality and safety advantages (1, 5, 8, 12, 13, 16) and can be monitored by automated instruments. One important drawback of these nonradiometric methods is that, occasionally, mycobacterial growth is present in the liquid medium culture but is not recognized by the instrumented detection system (11, 13). This problem was not frequently encountered with the radiometric approach. The device manufacturers acknowledge this drawback in their product inserts and recommend supplementary procedures to detect “instrument-negative” mycobacterial growth (Table 1) (2, 3, 17). However, it is unclear how frequently these growth detection failures occur or which mycobacterial species are most likely to produce them, although recent reports have indicated that Mycobacterium xenopi isolates are a particular problem (6, 11). Here, we address these questions by reviewing a 3-year experience with the Bactec MGIT 960 culture system in the Clinical Microbiology Laboratories at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Table 1.

Manufacturer-recommended supplementary procedures for detection of mycobacterial growth in instrument-negative cultures

| Manufacturer | Product | Recommended procedure |

|---|---|---|

| Becton, Dickinson | BBL MGIT | Perform a visual check of all instrument-negative tubes. If the tube appears visually positive (i.e., nonhomogeneous turbidity, small grains or clumps), it should be subcultured, acid-fast stained, and treated as a presumptive positive, provided the acid-fast smear result is positive (2). |

| bioMérieux | BacT/Alert MB | Instrument-negative cultures may be checked by smear and/or subcultured prior to discarding as negative (3). |

| Trek Diagnostic Systems | VersaTREK Myco | Perform a visual inspection of instrument-negative bottles for turbidity. If bottle is turbid, obtain a sample for acid-fast staining and subculture (17). |

Clinical specimens received for mycobacterial culture between January 2007 and December 2009 were processed using conventional procedures as previously described (4, 7, 9). After digestion-decontamination (if indicated) and concentration, the sediment was used to prepare an acid-fast stained smear and to inoculate both a Lowenstein-Jensen (LJ) slant and a mycobacterial growth indicator tube (MGIT; Becton, Dickinson) supplemented with an antibiotic mixture of polymyxin B, amphotericin B, nalidixic acid, trimethoprim, and azlocillin (PANTA) and growth supplement (Becton, Dickinson). MGIT broth cultures were initially incubated at 37°C for up to 42 days using automated Bactec 960 instruments, whereas LJ slants were incubated at 37°C for up to 56 days in an 8% CO2 incubator. After 42 days of incubation, all instrument-negative MGIT cultures (i.e., tubes in which growth had not been detected by the Bactec 960 instrument) were inspected visually for potential mycobacterial growth (Fig. 1), and a further workup was performed according to the algorithm described in Fig. 2. Acid-fast isolates were identified using AccuProbe hybridization probes (Gen-Probe, San Diego, CA) for M. tuberculosis complex, M. avium complex, M. kansasii, or M. gordonae. Isolates that could not be identified by the AccuProbe assays were forwarded to a reference laboratory for identification using PCR coupled with restriction endonuclease analysis, as previously described (14, 15).

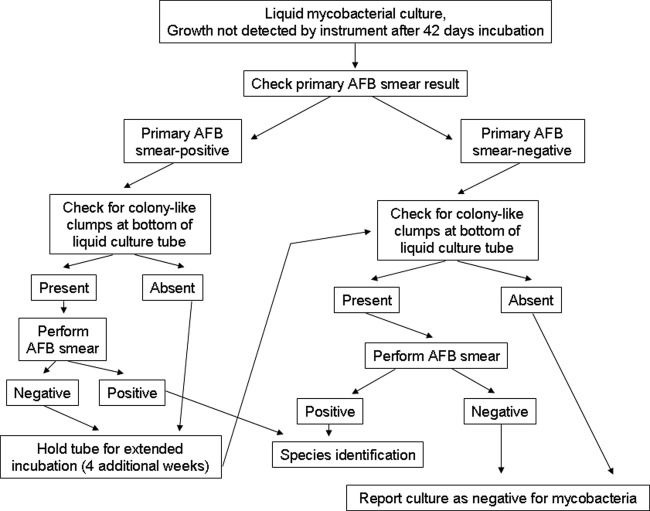

Fig 1.

Typical appearance of mycobacterial growth in instrument-negative broth culture. The organisms tend to form colony-like clumps (arrows) at the bottom of the tube, along the surface of the fluorescent indicator.

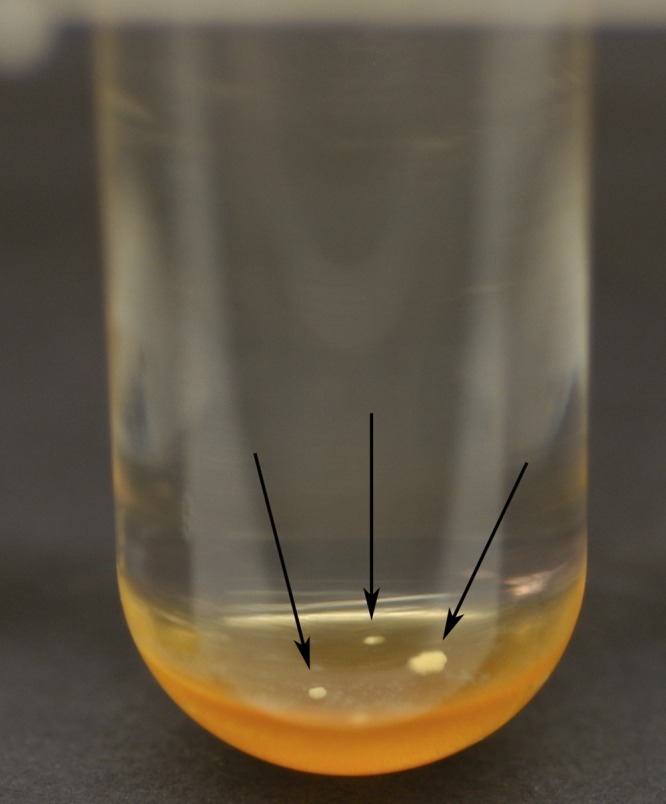

Fig 2.

Algorithm for handling instrument-negative cultures in the Bactec MGIT 960 system. At the completion of the standard 42-day incubation protocol, supplementary procedures were applied to the MGIT broth culture if the original specimen's primary AFB smear had been positive and/or colony-like clumps were visible at the bottom of the tube (see Fig. 1).

Over the 3-year study period, the laboratory received 10,263 specimens for mycobacterial culture. Among these, 1,323 (13%) were culture positive for mycobacteria (Table 2). Mycobacterial growth was detected by the Bactec 960 instruments within the routine 42-day incubation period in 1,189 of 1,323 culture-positive specimens (90%). These cultures, designated “instrument positive,” yielded 1,266 mycobacterial isolates. Mycobacterial growth in the remaining 134 (10%) culture-positive specimens was not detected by the Bactec 960 instrument. These 134 specimens were designated “instrument negative, culture positive,” or INCP. In 59 (44%) of 134 INCP specimens, mycobacterial growth was detected only by visual inspection of the MGIT broth tube and was not found in the cognate LJ slant culture. An additional 18 specimens were positive both by visual inspection of the MGIT and by LJ slant culture, for a total of 77 (∼1%) “instrument-negative, visual inspection-positive” (INVP) specimens from 9,074 instrument-negative specimens.

Table 2.

Comparison of instrument-positive and instrument-negative specimens according to specimen typea

| Specimen type | No. (%) of specimens yielding mycobacteria in culture (n = 1,323) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument positive (n = 1,189) | Instrument negative (n = 134) |

||||

| Visual inspection positive (n = 77) |

Visual inspection negative, LJ culture-positive (n = 57) | Total INCP (n = 134) | |||

| LJ culture-positive (N = 18) | LJ culture-negative (N = 59) | ||||

| Sputumb | 386 (32) | 14 (78) | 43 (73) | 39 (68) | 96 (72) |

| BAL fluid | 241 (20) | 2 (11) | 9 (15) | 9 (16) | 20 (15) |

| Lung or pleural tissue | 186 (16) | 1 (6) | 3 (5) | 4 (7) | 8 (6) |

| Lymph node | 80 (7) | 1 (6) | 1 (2) | 0 | 2 (1) |

| Woundc | 25 (2) | 0 | 1 (2) | 3 (5) | 4 (3) |

| Otherd | 271 (23) | 0 | 2 (3) | 2 (4) | 4 (3) |

LJ, Lowenstein-Jensen; INCP, instrument negative, culture positive; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage.

Includes expectorated and induced sputa.

Includes skin and subcutaneous tissue biopsy samples.

Includes tissue, fluid, or abscess material from the abdomen, pelvis, central nervous system, head and neck, bones, gastrointestinal tract, skin, deep soft tissue, breast, joints, or heart/pericardium.

When INVP specimens were stratified according to specimen type, sputum specimens were shown to be overrepresented in comparison to instrument-positive specimens. Whereas 32% of instrument-positive specimens were sputa, greater than twice that proportion (74%) of INVP specimens were sputum specimens (P < 0.0001). Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) were also overrepresented among isolates derived from INVP specimens (Table 3). NTM accounted for 96% of INVP isolates, compared with 83% of isolates from instrument-positive cultures (P = 0.0008). However, 3 Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from INVP specimens would not have been detected if visual inspection of instrument-negative cultures had not been performed, as the corresponding LJ slant cultures were negative. In 2 of those 3 cases, the M. tuberculosis isolates were derived from acid-fast bacillus (AFB) smear-positive specimens (one sputum specimen and one lung biopsy specimen) collected from patients who had had a recent diagnosis of active tuberculosis and had had other positive cultures and were receiving antituberculosis agents at the time of specimen collection. In the third case, however, the M. tuberculosis isolate was recovered from an AFB smear-negative, chest wall biopsy specimen collected from a patient with no prior positive mycobacterial cultures and who was not receiving antituberculosis therapy.

Table 3.

Mycobacterial species isolated from instrument-positive or instrument-negative specimensa

| Mycobacterial species | No. (%) of mycobacterial isolates (n = 1,403) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From instrument-positive specimens (n = 1,266) | From instrument-negative specimens (n = 137) |

||||

| From visual inspection-positive specimens (n = 79) |

From visual inspection-negative, LJ culture-positive specimens (n = 58) | All INCP isolates (n = 137) | |||

| LJ culture positive (n = 19) | LJ culture negative (n = 60) | ||||

| M. tuberculosis complex | 216 (17) | 0 | 3 (5) | 5 (9) | 8 (6) |

| Nontuberculous mycobacteria | 1,050 (83) | 19 (100) | 57 (95) | 53 (91) | 129 (94) |

| M. avium complex | 592 (56) | 7 (37) | 9 (16) | 29 (55) | 45 (35) |

| M. abscessus | 165 (16) | 0 | 0 | 2 (4) | 2 (2) |

| M. gordonae | 85 (8) | 5 (26) | 19 (33) | 7 (13) | 31 (24) |

| M. kansasii | 52 (5) | 0 | 3 (5) | 0 | 3 (2) |

| M. lentiflavum | 6 (1) | 1 (5) | 4 (7) | 3 (7) | 8 (6) |

| M. nebraskense | 1 (<1) | 0 | 8 (14) | 0 | 8 (6) |

| M. xenopi | 13 (1) | 5 (26) | 8 (14) | 0 | 13 (10) |

| M. chelonae | 9 (1) | 1 (5) | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 4 (3) |

| M. fortuitum | 50 (5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| M. marinum | 7 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| M. mucogenicum | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (4) | 2 (2) |

| M. scrofulaceum | 4 (<1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| M. bovis BCG | 1 (<1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| NTM, NOS | 65 (6) | 0 | 5 (9) | 6 (11) | 11 (9) |

INCP, instrument negative, culture positive; NTM, nontuberculous mycobacteria; NOS, not otherwise specified.

Among NTM isolates from INVP specimens, a spectrum of mycobacterial species was identified. M. gordonae, which rarely causes human infection, was overrepresented among NTM isolates from INVP specimens in comparison to NTM isolates whose growth was detected by the Bactec 960 instrument (32% in comparison to 8%, respectively; P < 0.0001). INVP specimens were also more likely than instrument-positive specimens to yield certain rarely recovered NTM, such as M. lentiflavum (7% of NTM isolates compared with 1%, respectively; P = 0.0004) and M. nebraskense (11% of NTM isolates compared with <1%, respectively; P < 0.0001). In contrast, certain NTM that are frequently implicated in human infections were underrepresented among isolates from INVP specimens in comparison to isolates from instrument-positive specimens. Species of the M. avium complex accounted for 21% of NTM from INVP specimens versus 56% of NTM from instrument-positive specimens (P < 0.0001). Also underrepresented were M. abscessus (0% of NTM from INVP specimens versus 16% of NTM from instrument-positive specimens; P < 0.0001) and M. fortuitum (0% of NTM from INVP specimens versus 5% of NTM from instrument-positive specimens; P = 0.04). However, INVP specimens were significantly more likely than instrument-positive specimens to yield M. xenopi (17% of NTM isolates compared with 1%, respectively; P < 0.0001). For the remaining NTM species isolated, significant differences between INVP and instrument-positive specimens in the frequencies of isolation were not found. Notably, 57 of 76 NTM isolates from INVP specimens (75%) were not recovered in the cognate LJ slant cultures and would not have been detected if instrument-negative broth cultures had not been visually inspected. Furthermore, 25 (44%) of those 57 isolates were derived from patients whose antecedent mycobacterial cultures (if any) had been negative and who had no history of mycobacterial infection.

The findings of this study present a challenge for the clinical laboratory. Only ∼1% of instrument-negative broth cultures contained mycobacterial growth, but fully 10% of all positive mycobacterial cultures were instrument negative, and in some cases the undetected organism was pathogenic (including M. tuberculosis) and was not recovered on solid medium. Rather than applying supplementary detection procedures to all instrument-negative broth cultures, which would be impractical, we recommend supplementary procedures for instrument-negative broth cultures containing colony-like clumps at the bottom of the tube after 42 days of incubation and for instrument-negative broth cultures of AFB smear-positive specimens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Elvina Lawrence for her assistance and technical expertise.

None of us has any conflicts of interest to declare.

No funding was obtained for the preparation of this report.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 4 April 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Alcaide F, Benitez MA, Escriba JM, Martin R. 2000. Evaluation of the BACTEC MGIT 960 and the MB/BacT systems for recovery of mycobacteria from clinical specimens and for species identification by DNA AccuProbe. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:398–401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Becton, Dickinson and Company 2011. BBL MGIT Mycobacterial Growth Indicator Tube package insert (7-ml tube). Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD [Google Scholar]

- 3. bioMérieux, Inc 2010. BacT/ALERT MB package insert. bioMérieux, Inc., Durham, NC [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2007. Laboratory detection and identification of mycobacteria; approved guideline. CLSI document M48-A. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hanna BA, et al. 1999. Multicenter evaluation of the BACTEC MGIT 960 system for recovery of mycobacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:748–752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Idigoras P, Beristain X, Iturzaeta A, Vicente D, Perez-Trallero E. 2000. Comparison of the automated nonradiometric BACTEC MGIT 960 system with Lowenstein-Jensen, Coletsos, and Middlebrook 7H11 solid media for recovery of mycobacteria. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 19:350–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kent P, Kubica G. 1985. Public health mycobacteriology: a guide for the level III laboratory. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, GA [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leitritz L, et al. 2001. Evaluation of BACTEC MGIT 960 and BACTEC 469TB systems for recovery of mycobacteria from clinical specimens of a university hospital with low incidence of tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3764–3767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Peres RL, et al. 2009. Comparison of two concentrations of NALC-NaOH for decontamination of sputum for mycobacterial culture. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 13:1572–1575 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pfyffer G, Palicova F. 2011. Mycobacterium: general characteristics, laboratory detection, and staining procedures, p 472–502 In Versalovic J, et al. (ed), Manual of clinical microbiology, vol 1 ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 11. Piersimoni C, Nista D, Bornigia S, Gherardi G. 2009. Unreliable detection of Mycobacterium xenopi by the nonradiometric Bactec MGIT 960 culture system. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:804–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rohner P, Ninet B, Beni A-M, Auckenthaler R. 2000. Evaluation of the BACTEC 960 automated nonradiometric system for isolation of mycobacteria from clinical specimens. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 19:715–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scarparo C, et al. 2002. Evaluation of the BACTEC MGIT 960 in comparison with BACTEC 460 TB for detection and recovery of mycobacteria from clinical specimens. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 44:157–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Steingrube VA, et al. 1995. PCR amplification and restriction endonuclease analysis of a 65-kilodalton heat shock protein gene sequence for taxonomic separation of rapidly growing mycobacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:149–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Telenti A, et al. 1993. Rapid identification of mycobacteria to the species level by polymerase chain reaction and restriction enzyme analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:175–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tortoli E, et al. 1999. Use of BACTEC MGIT 960 for recovery of mycobacteria from clinical specimens: multicenter study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3578–3582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Trek Diagnostic Systems 2010. VersaTREK Myco package insert. Trek Diagnostic Systems, Cleveland, OH [Google Scholar]