Abstract

Human cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection represents a major threat for heart transplant recipients (HTXs). CMV-specific T cells effectively control virus infection, and thus, assessment of antiviral immune recovery may have clinical utility in identifying HTXs at risk of infection. In this study, 10 CMV-seropositive (R+) pretransplant patients and 48 preemptively treated R+ HTXs were examined before and after 100 days posttransplant. Preemptive treatment is supposed to favor the immune recovery. CMV DNAemia and gamma interferon enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assay were employed to assess the viremia and immune reconstitution. HTXs could be categorized into three groups characterized by high (>100), medium (50 to 100), and low (<50) spot levels. Early-identified high responders efficiently controlled the infection and also maintained high immunity levels after 100 days after transplant. No episodes of grade ≥2R rejection occurred in the high responders. Midresponders were identified as a group with heterogeneous trends of immune reconstitution. Low responders were 41% and 21% of HTXs before and after 100 days posttransplant, respectively. Low responders were associated with a higher incidence of infection. The effect of viremia on immune recovery was investigated: a statistically significant inverse correlation between magnitude of viremia and immune recovery emerged; in particular, each 10-fold increase in viremia (>4 log10 DNAemia/ml) was associated with a 36% decrease of the ELISPOT assay spot levels. All episodes of high viremia (>4 log10 DNAemia/ml) occurred from 1 to 60 days after transplant. Thus, the concomitant evaluation of viremia and CMV immune reconstitution has clinical utility in identifying HTXs at risk of infection and may represent a helpful guide in making therapeutic choices.

INTRODUCTION

Heart transplantation is the primary and established procedure for treating a variety of diseases, including end-stage heart and coronary disease resulting in progressive loss of organ function (18). Despite the modern advances in surgical procedures, a recurrent problem is represented by posttransplant opportunistic infections that may fatally affect heart transplant recipients (HTXs). Among the infectious agents affecting transplant patients (reviewed in references 13, 27, and 43), cytomegalovirus (CMV) accounts for the most frequent cause of morbidity and mortality (21, 33). During the posttransplant phase, the immunosuppressive regimen and proinflammatory conditions predispose to CMV reactivation and shedding. In adult transplant patients, CMV frequently reactivates from the allograft donor or recipient and symptomatic clinical manifestations, including CMV disease, are strictly associated with the recipient CMV serostatus (12). Posttransplant CMV viremia may promote direct damage to the host and, indirectly, enhanced acute and chronic allograft rejection, also favoring the development of posttransplant vasculopathy (6, 8–10, 16, 28, 30, 32, 42, 44, 45). During the posttransplant phase, virus replication may be effectively controlled with antiviral drug administration; however, intrinsic antiviral drug toxicity, poor patient compliance, and eventual development of drug-resistant strains discourage the prolonged administration of drugs. CMV-specific T cells have the beneficial effect of controlling the virus infection (4, 14, 15, 17, 20, 38) and limiting the potential virus-induced vascular damage (31, 41); thus, the antiviral immune reconstitution is considered one of the most auspicious achievements in order to control the virus's ability to induce disease. Most of the studies on T-cell immune reconstitution in HTXs were performed in prophylactically treated patients. Antiviral prophylaxis effectively inhibits virus replication but is also associated with a delayed priming of T-cell immune reconstitution and a higher incidence of late-onset CMV disease (3, 5, 17, 21, 22). Antiviral preemptive therapy, allowing a limited degree of viral replication and antigen exposure, is thought to be beneficial for antiviral T-cell immune reconstitution (15). As shown in other solid organ transplant settings (2), preemptive and prophylactic antiviral strategies, pharmacological treatment, and preexisting levels of antiviral immunity may have a dramatic impact on the antiviral immune reconstitution. Thus, immunological monitoring of the antiviral T-cell reconstitution is becoming an appealing and attractive strategy. The trend of posttransplant immune reconstitution may provide insights and critical notions on the risk of developing CMV-induced complications. For this reason, routine immunological monitoring of transplant patients has been proposed (14, 17). In this study, we present the results of a cross-sectional study analyzing the pattern of antiviral immune reconstitution in a cohort of 48 CMV-seropositive (R+) HTXs treated with preemptive therapy compared to 10 pretransplant R+ patients. This study is an observational analysis of how T-cell immune reconstitution occurs in the posttransplant phase when patients are preemptively treated and exposed to limited virus replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and clinical definitions.

Forty-eight adult HTXs and 10 pretransplant patients were enrolled in the study from September 2006 to July 2011. None of the pretransplant patients underwent heart transplantation during the study follow-up. Patients were voluntarily recruited among the ones on the transplantation list (pretransplant group) and within 100 or after 100 days posttransplant. Twenty-nine patients were analyzed both before and after 100 days posttransplant, while 19 patients were analyzed once for collection of a single data point before or after 100 days posttransplant. Patients were voluntarily recruited to donate 10 ml of peripheral blood for gamma interferon (IFN-γ) enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assay and CMV DNAemia determination. The Internal Review Board (IRB) of Padua General Hospital approved all the medical procedures. A signed written consent disclosing the aims and goals of the study was required from each enrolled patient. A written explanation with terms and privacy policy was also provided to the enrolled patients and their primary care physicians. The enrollment exclusion criteria were being CMV seronegative (R−; CMV IgG negative) before transplantation or having preexisting or acquired immunodeficiencies.

Treatments and clinical definitions.

CMV infection is defined as detection of viremia at >1,000 copies/ml of whole blood. CMV disease was defined as symptomatic clinical manifestations with fever and malaise associated with detectable CMV viremia and not ascribable to any other infection or condition. For all transplant patients, the transplant-conditioning regimen included antithymocyte treatment (recombinant antithymocyte globulin, 20 mg/kg of body weight/day) for 4 days posttransplant. The immunosuppressive maintenance scheme is shown in Table 1. Transplant patients were treated according to a preemptive strategy, defined as described previously (21, 29, 35, 37) and consisting of the initiation of antiviral treatment upon the detection of a viral load (CMV DNAemia) above 5,000 copies/ml. The threshold of 5,000 copies/ml to initiate anti-CMV preemptive antiviral treatment was arbitrarily chosen on the basis of previous observations on safety and effectiveness (data not shown). Anti-CMV preemptive treatment included oral administration of valganciclovir (Valcyte; Roche) at a standard dose (900 mg twice a day) or intravenous ganciclovir (5 mg twice a day) corrected according to renal function. Antiviral therapy was considered successful when two sequential negative CMV DNAemia tests were obtained. Cases of CMV-resistant strains were not detected among the transplant patients. Cardiac biopsy specimens were analyzed and graded according to the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) (39). Endomyocardial biopsy specimens (EMCBs) were collected on a weekly basis during the first month posttransplant and every 15 days within 30 to 90 days posttransplant. From days 90 to 360, EMCBs were analyzed every 30 days. Rejections with a score of ≥2R, formerly known as a score of ≥3A, were treated with intravenous methylprednisolone (1 g/day) for 3 days, with the dose being adjusted according to physician discretion. During the grade ≥2R rejection, patients were not treated with antiviral prophylaxis. Patients' demographic and clinical data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients' characteristicsa

| Characteristic | Resultb |

|---|---|

| Total no. of subjects enrolled | 58 |

| Pretransplant patients (control group) | 10 (17) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 4 (7) |

| Male | 6 (10) |

| Range (median) age (yr) | 26-68 (58) |

| Transplant patients (HTXs) | |

| R+/D+ and R+/D− | 48 (83) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 8 (14) |

| Male | 40 (69) |

| Range (median) age (yr) | 11-74 (59) |

| Immunosuppressive regimen | |

| CNI + MMF + steroids | 21 (44) |

| CNI + azathioprine + steroids | 20 (42) |

| Including mTOR inhibitors | 7 (14) |

| Transplant-related mortality | 2 (4) |

| Mortality from other causes | 1 (2) |

| Acute rejection episodes | 17 (35) |

| Grade 1R rejection (formerly known as 1A) | 9 (19) |

| Grade 2R rejection (formerly known as 3A) | 8 (16) |

| Posttransplant CMV DNAemia | 36 (75) |

| Treatment for CMV infection during posttransplant phase | 29c (60) |

Abbreviations: D+ and D−, seropositive or seronegative donor; CNI, calcineurin inhibitors; MMF, mycophenolate-mofetil; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin.

Results are presented as number (percent) of patients unless indicated otherwise.

Seven patients were not preemptively treated because CMV DNAemia was <5,000 copies/ml.

Evaluation of CMV DNAemia and CMV serology test.

Routine surveillance for viral reactivation or infection comprised weekly determination of whole-blood CMV DNAemia during the first 100 days posttransplant and continued thereafter if clinically indicated. CMV DNAemia was evaluated using an in-house real-time PCR-based method on whole blood. PCR primers, probes, and amplification conditions were described previously (25). The lowest detection limit corresponded to 1,000 viral copies/ml of whole blood. CMV IgG and IgM serology was assessed using diagnostic-grade IgG and IgM enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (Enzygnost; Dade Behring).

Evaluation of immune response.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were extracted and purified by Ficoll (GE Healthcare) separation. PBMCs were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% human type AB serum (Sigma-Aldrich) and seeded at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml in 96-well IFN-γ-coated ELISPOT assay plates (Autoimmun Diagnostika). For each patient, duplicate wells were incubated with phytohemagglutinin (PHA; 10 μg/ml; Autoimmun Diagnostika) or phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; 50 ng/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) and ionomycin (1 μM; Sigma-Aldrich), a CMV-specific pp65 (ppUL83) peptide mix (10 μg/ml; Autoimmun Diagnostika), or, as a negative control, a peptide mix containing in randomly arranged order the same amino acid residues of pp65 (10 μg/ml). PHA and PMA-ionomycin were considered positive controls. ELISPOT assay images were acquired and analyzed using an automated image scanner (Aelvis). ELISPOT assay results are expressed as the number of CMV pp65-specific IFN-γ spot-forming colonies (SFCs)/200,000 PBMCs. pp65 was chosen as a stimulus since it is considered to be among the major immunodominant antigens encoded by CMV (19, 24, 46) and has been widely used to detect CMV-specific T-cell responses in humans (1, 2, 7, 23, 41). In human trials, pp65 has also been shown to be a biologically relevant target to resolve and prevent clinically relevant infections (11, 26).

All results shown are background subtracted (sample minus negative control). Cytokine flow cytometry showed that pp65-specific IFN-γ-secreting cells detected using the ELISPOT test corresponded to CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (data not shown). All CMV IgG-seropositive patients reacted to the pp65 (ppUL83) peptide mix and whole inactivated CMV antigen in the ELISPOT assay (data not shown).

Statistical analysis.

The association between rejection and viremia was calculated using Pearson's chi-square test and 1 degree of freedom (see Table 2). A two-tailed Mann-Whitney nonparametric test was used to assess differences in ELISPOT levels in HTXs with or without viremia or immunity generated after viremia (see Fig. 1 and 4C). P values of <0.05 were considered significant. The correlation between the ELISPOT assay result and viremia (as CMV DNAemia) was investigated by the linear regression approach. Since both of these variables (the logeli and logvir variables) were strongly right skewed, the values were log10 transformed. In order to include nonviremic patients in the same model, a categorical (binary) variable (novir; 1 in nonviremic patients, 0 in the viremic population) was also included in the model.

Table 2.

Time of occurrence of CMV infection and ≥2R rejection score

| Occurrence of CMV viremia | No. (%) of patients (48) | No. of patients with a ≥2R rejection scorea |

|---|---|---|

| No detectable viremia | 12 (25) | 0 |

| Viremia before 100 days posttransplant | 26 (54) | 6 |

| Viremia after 100 days posttransplant | 2 (4) | 1 |

| Viremia before and after 100 days posttransplant | 8 (17) | 1 |

A rejection score of ≥2R was formerly known as a score of 3A.

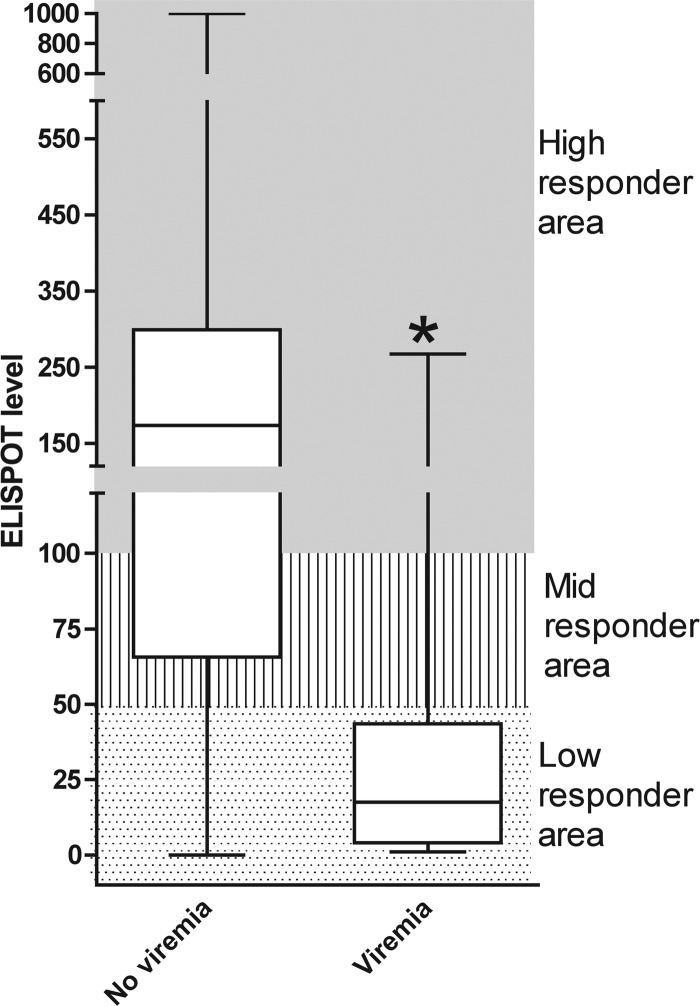

Fig 1.

ELISPOT assay as a predictor of CMV infection. Box-and-whisker plot of CMV-specific IFN-γ ELISPOT levels of HTXs who controlled or experienced CMV viremia within 60 days after ELISPOT determination. The rectangular box connects the upper and lower quartiles and the median. Whiskers connect the upper and lower extremes. The ELISPOT level corresponds to the number of CMV pp65-specific IFN-γ spots/200,000 PBMCs. ELISPOT assay data included those for the test performed from 30 to 360 days posttransplantation. *, P < 0.05.

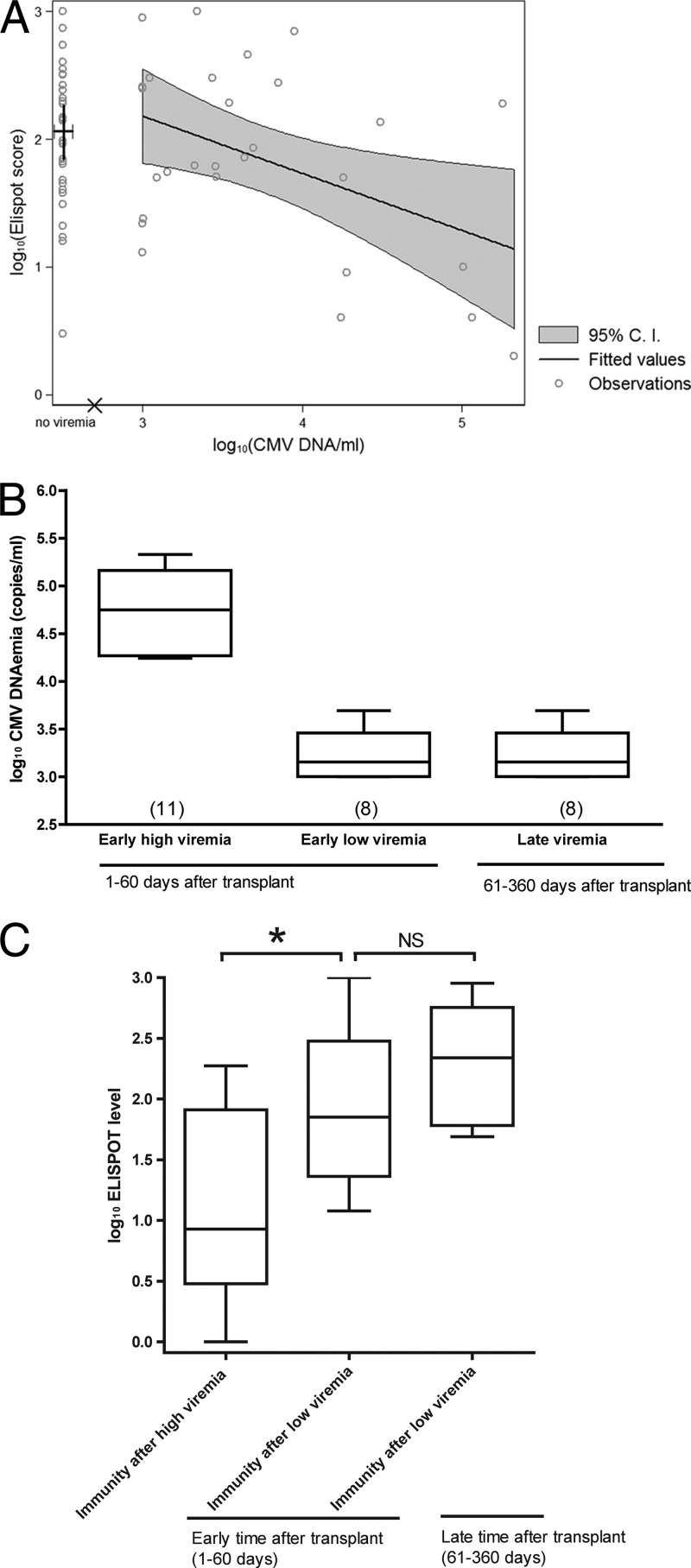

Fig 4.

CMV-specific ELISPOT levels generated after CMV viremia. CMV viremia and ELISPOT assay values were log10 transformed. (A) Correlation between log10 CMV DNA viremia (logvir) and log10 ELISPOT assay score (logeli). Hollow circles represent observations for 27 HTXs who experienced viremia before ELISPOT determination. The discontinuity is indicated by the × sign on the horizontal axis. The large cross in the no-viremia area indicates the mean and the 95% confidence interval (C.I.) of logeli in nonviremic patients, corresponding to a mean ELISPOT score of 116 (95% confidence interval, 71 to 190). The continuous logeli range from 3 to 5.33 (CMV DNA load, 1,000 to 213,492 copies/ml) is covered by the regression line and the related 95% confidence interval (gray area). Overall significance: P = 0.0111 and R2 = 0.1438. (B) Box-and-whiskers plot of high (>4 log10 CMV copies/ml) and mild-low (<4 log10 CMV copies/ml) CMV viremia during early (1 to 60) and late (61 to 360 days) times after transplant. Numbers in parentheses display the number of patients for each group. (C) Box-and-whiskers plot of ELISPOT levels of HTXs after high or mild-low viremia from 1 to 60 or 61 to 360 days after transplant. ELISPOT levels were determined after a median of 28 days (range, 6 to 90 days) after viremia. Data for HTXs who did not experience viremia or HTXs who experienced viremia after ELISPOT determinations were not included in the graphs. *, P < 0.05; NS, not significant.

RESULTS

Transplant outcome.

Table 1 shows the main clinical characteristics of the patients studied. Three HTXs died during the posttransplant phase: two (4%) HTXs died from transplant-related sequelae and one (2%) died from other causes independent of the transplant. Eight (17%) HTXs experienced posttransplant grade ≥2R allograft rejection. This fraction is slightly higher than the general trend (40). CMV viremia occurred in 36 (75%) HTXs, and 29 (60%) required antiviral treatment; 7 HTXs were not treated since the CMV viremia was below the 5,000-copy/ml threshold considered for preemptive antiviral treatment. Two (3%) HTXs experienced symptomatic CMV infection. CMV viremia occurred during the 100 days posttransplant in 26 (54%) HTXs, while 2 (4%) HTXs experienced viremia after 100 days posttransplant and 8 (17%) HTXs experienced viremia both before and after 100 days posttransplant. Twelve (25%) HTXs did not experience CMV viremia in the posttransplant phase. Of the seven patients treated with mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors, two HTXs experienced posttransplant CMV viremia: one HTX within 100 days posttransplant and one HTX both before and after 100 days posttransplant. The results corroborate previous studies showing that patients treated with mTOR inhibitors display a lower incidence of CMV viremia. Table 2 shows the incidence of rejection in respect to CMV viremia: the data show that there were no cases of grade ≥2R rejection in HTXs with no detectable CMV viremia, while CMV viremia occurred in the eight cases of grade ≥2R rejection. In five HTXs with grade ≥2R allograft rejection, detectable CMV viremia occurred concurrently with or preceded allograft rejection. In three HTXs, grade ≥2R rejection occurred without concurrence or history of detectable levels of CMV viremia. A statistical analysis of the association between viremia and rejection was not possible because there was not sufficient statistical power.

IFN-γ ELISPOT assay as a diagnostic tool to assess immune reconstitution in transplants settings.

In order to assess the ELISPOT level indicating protection from CMV viremia, the ELISPOT levels of HTXs who did not experience CMV viremia were compared to the ELISPOT levels of HTXs who developed CMV viremia (Fig. 1). Patients protected from CMV viremia displayed statistically significantly higher ELISPOT levels (median, 173 spots; range, 0 to 1,000 spots) than HTXs with the occurrence of viremia (median, 18 spots; range, 1 to 267 spots). On the basis of the ELISPOT levels, we arbitrarily grouped HTXs into high responders (>100 spots), midresponders (>50 to <100 spots), and low responders (<50 spots).

Posttransplant CMV-specific T-cell immune reconstitution.

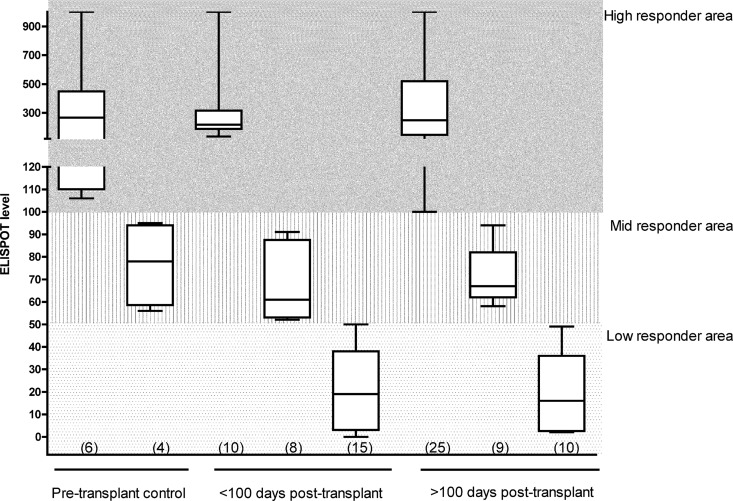

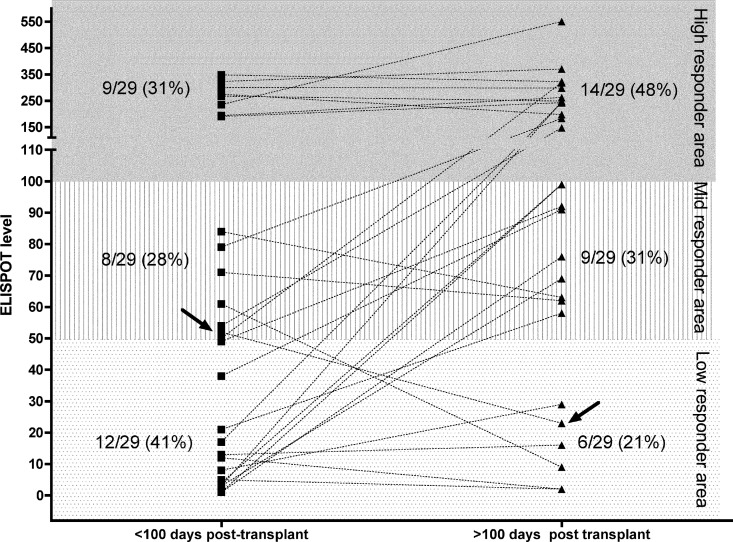

We investigated the trend of CMV-specific T-cell reconstitution in 10 pretransplant R+ subjects (control group) and the 48 HTXs enrolled in the study: HTXs were divided into before and after 100 days posttransplant on the basis of the timing of transplantation (Fig. 2): the pretransplant R+ control group could be stratified as high and midresponders with median ELISPOT levels of 267 spots (range, 106 to 1,000 spots) and 78 spots (range, 56 to 95 spots), respectively. In the posttransplant phase, the high-responder HTXs displayed median ELISPOT levels of 218 spots (range, 135 to 1,000 spots) and 249 spots (range, 100 to 1,000 spots), respectively, at <100 days and >100 days. The midresponders displayed median ELISPOT levels of 61 spots (range, 52 to 91 spots) and 67 spots (range, 58 to 94 spots), respectively, at <100 days and >100 days, while the low responders displayed medians ELISPOT levels of 23 spots (range, 0 to 49 spots) and 59 spots (range, 2 to 49 spots), respectively, at <100 days and >100 days posttransplant. As expected, low responders could be found only in the transplant group. For 29/48 HTXs enrolled in the study, we had prospective data from both before and after 100 days posttransplant (Fig. 3): the data show that at <100 days posttransplant, 9/29 (31%) HTXs were high responders, 8/29 (28%) HTXs were midresponders, and 12/29 (41%) HTX were low responders. When the same patients were analyzed at >100 days posttransplant, 14/29 (48%) HTXs were high responders, 9/29 (31%) HTXs were midresponders, and 6/29 (21%) HTXs were low responders. All HTXs who were high responders at <100 days were also high responders at >100 days posttransplant, while 4/12 HTXs who were low responders at <100 days were still low responders at >100 days. Midresponders appeared to be a transitory group, where HTXs later become high responders. Two of eight HTXs who were midresponders at <100 days became low responders at >100 days posttransplant. In the group of HTXs who acquired antiviral immune reconstitution from low to high or mid- to high responders, no association with previous CMV viremia episodes, magnitude, or duration and no difference in therapeutic management or transplant conditioning were found. The acquisition of antiviral T-cell immunity was not associated with grade ≥2R rejection.

Fig 2.

CMV-specific immunity in 10 pretransplant patients and 48 HTXs. Box-and-whiskers plot of pretransplant (control group), early (<100 days posttransplant), and late (>100 days posttransplant) CMV-specific IFN-γ ELISPOT levels in HTXs. Data are for 19 HTXs with single ELISPOT assay determinations taken <100 or >100 days after transplant and ELISPOT assay and 29 HTXs followed prospectively both before and after 100 days after transplant. Numbers in parentheses display the number of ELISPOT assay determinations done for each group.

Fig 3.

Immune reconstitution of 29 HTXs followed prospectively before and after 100 days after transplant. Dotted lines show HTX IFN-γ ELISPOT levels before and after 100 days posttransplant. Arrows indicate the CMV-specific immune response of one HTX who experienced CMV disease. For the other patient experiencing CMV disease, we did not have data from sequential time points.

Effect of CMV viremia on immune reconstitution.

In order to assess the impact of viremia on the CMV-specific immune reconstitution, we investigated 27 HTXs for whom CMV viremia preceded the ELISPOT determination (Fig. 4A). The HTXs who did not experience viremia or HTXs who experienced viremia after ELISPOT determinations were not included in the analysis. The data shown in Fig. 4A include all the cases of viremia occurring before the ELISPOT assay from 1 to 360 days after transplant. The ELISPOT values were detected after a median of 28 days (range, 6 to 90 days) after the peak viremia episode. The data show a statistically significant correlation of viremia in respect to generation of a CMV-specific T-cell response (P = 0.0111; R2 = 0.1438); in particular, each 10-fold increase in viremia was associated with a 36% decrease of the ELISPOT level. All episodes of viremia of >4 log10 CMV copies/ml occurred during the 1 to 60 days after the transplant. In order to avoid biases due to differences in treatments and immunosuppression regimen, the effect of viremia on immune recovery was analyzed at two distinct time points early (1 to 60 days) and late (61 to 360 days) after transplant that we arbitrarily defined. Early after transplant, HTXs were equally distributed among patients who experienced high or mild-low viremia, while late after transplant, HTXs experienced only mild-low viremia (Fig. 4B).

The data show that early after transplant there were statistically significant differences between ELISPOT levels generated after high and mild-low viremia. There was no statistically significant difference between early and late phases after transplant in ELISPOT levels preceded by mild-low viremia (Fig. 4C).

DISCUSSION

The posttransplant period is considered a critical phase when infections may cause disease and have detrimental effects on the host. In recent years, several pieces of evidence have suggested that CMV-specific T-cell immune reconstitution may have multiple beneficial effects, including a reduced risk of infection and lower rates of rejection and vasculopathy; thus, assessment of immune recovery may be an appealing strategy to predict the patients' clinical outcome and, eventually, a helpful tool to adjust the therapeutic interventions.

In this study, we focused our attention on the immune reconstitution of a cohort of preemptively treated R+ patients compared to a control cohort represented by pretransplant R+ HTXs. Other studies on immune reconstitution focused on patients treated with antiviral prophylaxis, including R+ and R− patients that did not experience viremia during the prophylaxis regimen. In the settings that we studied, we analyzed a population homogeneous for the preemptive antiviral treatment received and also immunologically homogeneous since all patients exhibited preexisting levels of CMV-specific immunity. Thus, the major variables that may occur during the posttransplant phase are (i) graft rejection and (ii) viremia episodes. Other authors have shown that a rapid immune recovery was associated with a reduced incidence of allograft rejection and vascular disease (41). In this study, the number of cases with a reduced incidence of allograft rejection and vascular disease did not have statistical power to prove an association between viremia and rejection. The classification into high, mid-, and low responders, deduced from the pattern of CMV-specific T-cell immunity of HTXs controlling CMV versus HTXs infected, was revealed to be useful to stratify HTX antiviral immunological reconstitution: in particular, the data show that high responders were a homogeneous group able to control CMV viremia and preserve stable high antiviral immune levels during the late posttransplant phase. High responders were present in the pretransplant R+ control group and among HTXs during the early and late posttransplant phases. The HTXs identified as high responders early after transplant may benefit from a different antiviral program protocol since the immune system is autonomously competent in controlling virus infection.

The midresponder group could be found in both the pretransplant R+ group and among the early and late HTXs. This group appears to be in a dynamic and transitory phase during which HTXs may later become high, mid-, or even low responders. This group of patients should be carefully monitored for both CMV viremia and T-cell immunity to assess whether the antiviral immune reconstitution improves, becomes steady, or, in the worse case, decreases. We could not find significant associations between specific pharmacological treatments or CMV viremia and the reduction in antiviral immune response.

Low responders were present only among HTXs and not pretransplant R+ controls. Low responders represented 41% and 21% of HTXs, respectively, during the early and late posttransplant phases. Most of the early-phase-detected low responders will eventually become high or midresponders during the late posttransplant phase. Late-phase-recognized low responders represent the very critical HTXs at risk of developing late-onset CMV infection. Despite being preemptively treated and experiencing numerous episodes of CMV viremia, this group of patients failed to reconstitute protective levels of antiviral immune response. A group of patients defined as “chronic never do well,” characterized by numerous episodes of viral and opportunistic infections, was already reported (34, 36) and may include the low-responder HTXs identified to be unable to efficiently reconstitute protective levels of antiviral immunity. The underlying reasons explaining why low responders fail to reconstitute an adequate antiviral immunity are unknown, but nevertheless, their identification is critical in order to provide these patients with appropriate treatment and closer medical attention.

We investigated if there was any association or difference in terms of viremia or pharmacological treatments in the group of HTXs whose antiviral immune recovery improved (low to mid-, low to high, and mid- to high responders); however, no significant association was found. In this report, the data show that high CMV viremia preceded an impaired CMV-specific T-cell response, while low or moderate viremia preceded steady or increased levels of a CMV-specific T-cell response. It is important to consider that all the high-viremia episodes occurred during the early phase (1 to 60 days) after transplant. It is plausible to speculate that (i) depending on the magnitude and the timing of occurrence, CMV viremia may boost or depress the immune reconstitution, (ii) the impaired immunity succeeding high viremia may be a transient phase, and (iii) impaired immunity after high viremia may depend upon low preexisting levels of immunity. In order to fully elucidate the impact of the magnitude of CMV viremia on immune reconstitution, a prospective longitudinal study, analyzing at several time points, both early and late posttransplant, the CMV immune response before and after viremia is recommended.

Taken together, immunological and virological monitoring provides a better prospects for accurate clinical decision making and management of transplant patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Padua General Hospital, Azienda Ospedaliera di Padova, for providing us with the IFN-γ ELISPOT assay plates. We thank Gianluca Torregrossa for medical advice. We also thank Alice Bianchin, Angela Bozza, and Valentina Fornasiero for technical aid.

This research was supported by Ricerca Sanitaria Finalizzata grant no. 271/07, the University of Padua Progetto di Ateneo 2006 (CPDA063398), and the Italian Ministry of Education National Strategic Interest Research Program, PRIN (2007CCW84J_002).

We all declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 29 March 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Abate D, et al. 2012. Diagnostic utility of human cytomegalovirus-specific T-cell response monitoring in predicting viremia in pediatric allogeneic stem-cell transplant patients. Transplantation 93:536–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abate D, et al. 2010. Evaluation of cytomegalovirus (CMV)-specific T cell immune reconstitution revealed that baseline antiviral immunity, prophylaxis, or preemptive therapy but not antithymocyte globulin treatment contribute to CMV-specific T cell reconstitution in kidney transplant recipients. J. Infect. Dis. 202:585–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baldanti F, Lilleri D, Gerna G. 2008. Monitoring human cytomegalovirus infection in transplant recipients. J. Clin. Virol. 41:237–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bunde T, et al. 2005. Protection from cytomegalovirus after transplantation is correlated with immediate early 1-specific CD8 T cells. J. Exp. Med. 201:1031–1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cummins NW, Deziel PJ, Abraham RS, Razonable RR. 2009. Deficiency of cytomegalovirus (CMV)-specific CD8+ T cells in patients presenting with late-onset CMV disease several years after transplantation. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 11:20–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dumortier J, et al. 2008. Human cytomegalovirus secretome contains factors that induce angiogenesis and wound healing. J. Virol. 82:6524–6535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dunn HS, et al. 2002. Dynamics of CD4 and CD8 T cell responses to cytomegalovirus in healthy human donors. J. Infect. Dis. 186:15–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Epstein SE, et al. 1996. The role of infection in restenosis and atherosclerosis: focus on cytomegalovirus. Lancet 348(Suppl 1):s13–s17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fateh-Moghadam S, et al. 2003. Cytomegalovirus infection status predicts progression of heart-transplant vasculopathy. Transplantation 76:1470–1474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fearon WF, et al. 2007. Changes in coronary arterial dimensions early after cardiac transplantation. Transplantation 83:700–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Feuchtinger T, et al. 2010. Adoptive transfer of pp65-specific T cells for the treatment of chemorefractory cytomegalovirus disease or reactivation after haploidentical and matched unrelated stem cell transplantation. Blood 116:4360–4367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fisher RA. 2009. Cytomegalovirus infection and disease in the new era of immunosuppression following solid organ transplantation. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 11:195–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fishman JA. 2007. Infection in solid-organ transplant recipients. N. Engl. J. Med. 357:2601–2614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gerna G, Lilleri D. 2006. Monitoring transplant patients for human cytomegalovirus: diagnostic update. Herpes 13:4–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gerna G, et al. 2006. Monitoring of human cytomegalovirus-specific CD4 and CD8 T-cell immunity in patients receiving solid organ transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 6:2356–2364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gredmark S, Jonasson L, Van Gosliga D, Ernerudh J, Soderberg-Naucler C. 2007. Active cytomegalovirus replication in patients with coronary disease. Scand. Cardiovasc. J. 41:230–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Griffiths P, Whitley R, Snydman DR, Singh N, Boeckh M. 2008. Contemporary management of cytomegalovirus infection in transplant recipients: guidelines from an IHMF workshop, 2007. Herpes 15:4–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hunt SA, Haddad F. 2008. The changing face of heart transplantation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 52:587–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kern F, et al. 2002. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) phosphoprotein 65 makes a large contribution to shaping the T cell repertoire in CMV-exposed individuals. J. Infect. Dis. 185:1709–1716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kirchner A, et al. 2008. Dissection of the CMV specific T-cell response is required for optimized cardiac transplant monitoring. J. Med. Virol. 80:1604–1614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kotton CN. 2010. Management of cytomegalovirus infection in solid organ transplantation. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 6:711–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Legendre C, Pascual M. 2008. Improving outcomes for solid-organ transplant recipients at risk from cytomegalovirus infection: late-onset disease and indirect consequences. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:732–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maecker HT, et al. 2008. Precision and linearity targets for validation of an IFNgamma ELISPOT, cytokine flow cytometry, and tetramer assay using CMV peptides. BMC Immunol. 9:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McLaughlin-Taylor E, et al. 1994. Identification of the major late human cytomegalovirus matrix protein pp65 as a target antigen for CD8+ virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J. Med. Virol. 43:103–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mengoli C, et al. 2004. Assessment of CMV load in solid organ transplant recipients by pp65 antigenemia and real-time quantitative DNA PCR assay: correlation with pp67 RNA detection. J. Med. Virol. 74:78–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Micklethwaite KP, et al. 2008. Prophylactic infusion of cytomegalovirus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes stimulated with Ad5f35pp65 gene-modified dendritic cells after allogeneic hemopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 112:3974–3981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mocarski ES, Shenk T, Pass RF. 2001. Cytomegaloviruses and their replication, p 2629–2673 In Knipe DM, Howley PM. (ed), Fields virology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 28. Paya CV. 1999. Indirect effects of CMV in the solid organ transplant patient. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 1(Suppl 1):8–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Paya CV. 2001. Prevention of cytomegalovirus disease in recipients of solid-organ transplants. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32:596–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Potena L, et al. 2003. Relevance of cytomegalovirus infection and coronary-artery remodeling in the first year after heart transplantation: a prospective three-dimensional intravascular ultrasound study. Transplantation 75:839–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Potena L, et al. 2006. Acute rejection and cardiac allograft vascular disease is reduced by suppression of subclinical cytomegalovirus infection. Transplantation 82:398–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Potena L, Valantine HA. 2007. Cardiac allograft vasculopathy and insulin resistance—hope for new therapeutic targets. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 36:965–981, ix [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Razonable RR. 2005. Epidemiology of cytomegalovirus disease in solid organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 62:S7–S13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rubin RH. 2002. Overview: pathogenesis of fungal infections in the organ transplant recipient. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 4(Suppl 3):12–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rubin RH. 1991. Preemptive therapy in immunocompromised hosts. N. Engl. J. Med. 324:1057–1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rubin RH, Schaffner A, Speich R. 2001. Introduction to the Immunocompromised Host Society Consensus Conference on Epidemiology, Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Infections in Solid-Organ Transplant Patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33(Suppl 1):S1–S4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schmidt GM, et al. 1991. A randomized, controlled trial of prophylactic ganciclovir for cytomegalovirus pulmonary infection in recipients of allogeneic bone marrow transplants. The City of Hope-Stanford-Syntex CMV Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 324:1005–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sester U, et al. 2005. Differences in CMV-specific T-cell levels and long-term susceptibility to CMV infection after kidney, heart and lung transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 5:1483–1489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stewart S, et al. 2005. Revision of the 1990 working formulation for the standardization of nomenclature in the diagnosis of heart rejection. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 24:1710–1720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Taylor DO, et al. 2009. Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Twenty-Sixth Official Adult Heart Transplant Report-2009. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 28:1007–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tu W, et al. 2006. T-cell immunity to subclinical cytomegalovirus infection reduces cardiac allograft disease. Circulation 114:1608–1615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Valantine H. 2004. Cardiac allograft vasculopathy after heart transplantation: risk factors and management. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 23:S187–S193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Valantine HA. 2004. The role of viruses in cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Am. J. Transplant. 4:169–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vamvakopoulos J, Hayry P. 2003. Cytomegalovirus and transplant arteriopathy: evidence for a link is mounting, but the jury is still out. Transplantation 75:742–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Weill D. 2001. Role of cytomegalovirus in cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 3(Suppl 2):44–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wills MR, et al. 1996. The human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) response to cytomegalovirus is dominated by structural protein pp65: frequency, specificity, and T-cell receptor usage of pp65-specific CTL. J. Virol. 70:7569–7579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]