Abstract

Background

Understanding the mechanisms responsible for cellular responses depends on the systematic collection and analysis of information on the main biological concepts involved. Indeed, the identification of biologically relevant concepts in free text, namely genes, tRNAs, mRNAs, gene products and small molecules, is crucial to capture the structure and functioning of different responses.

Results

In this work, we review literature reports on the study of the stringent response in Escherichia coli. Rather than undertaking the development of a highly specialised literature mining approach, we investigate the suitability of concept recognition and statistical analysis of concept occurrence as means to highlight the concepts that are most likely to be biologically engaged during this response. The co-occurrence analysis of core concepts in this stringent response, i.e. the (p)ppGpp nucleotides with gene products was also inspected and suggest that besides the enzymes RelA and SpoT that control the basal levels of (p)ppGpp nucleotides, many other proteins have a key role in this response. Functional enrichment analysis revealed that basic cellular processes such as metabolism, transcriptional and translational regulation are central, but other stress-associated responses might be elicited during the stringent response. In addition, the identification of less annotated concepts revealed that some (p)ppGpp-induced functional activities are still overlooked in most reviews.

Conclusions

In this paper we applied a literature mining approach that offers a more comprehensive analysis of the stringent response in E. coli. The compilation of relevant biological entities to this stress response and the assessment of their functional roles provided a more systematic understanding of this cellular response. Overlooked regulatory entities, such as transcriptional regulators, were found to play a role in this stress response. Moreover, the involvement of other stress-associated concepts demonstrates the complexity of this cellular response.

Background

Scientific literature represents a valuable source of biological information, in particular on the description of biological entities that we can find in a cellular system and how they are related to each other. To identify references to these entities in texts, here designated as biological concepts, literature mining approaches can be applied. Lately, these approaches have provided for substantial knowledge discovery in diverse biological domains [1-7]. In systems biology, this is of particular interest, since literature-derived evidences can assist in the reconstruction of biochemical and signalling network models. Taking advantage of information retrieval and extraction methodologies it is possible to cover a multitude of biological entities and many other aspects that characterise these complex biological representations. In this work, literature mining was used to get a deep view on the structure of the stringent response in E. coli, which was then helpful in the mathematical modelling of this stress response [8].

This stress response has been studied in the last four decades, but many of the cellular mechanisms involved are still unclear [9-14]. Studies have shown that the accumulation of unusual guanosine nucleotides, collectively called (p)ppGpp, is the hallmark of the stringent response of E. coli [15-18] (Figure 1). Such accumulation is known to be controlled by the activity of two enzymes, the ribosome-bound RelA enzyme (ppGpp synthetase I) that synthesises (p)ppGpp nucleotides upon the depletion of amino acids [19] and the bifunctional SpoT enzyme (ppGpp synthetase II) that is responsible for maintaining the intracellular levels of (p)ppGpp nucleotides via enzymatic degradation [20]. The (p)ppGpp-mediated response involves the control of the genetic expression by direct interaction of the (p)ppGpp nucleotides with the RNA polymerase (RNAP) [21,22], activating the transcription of genes coding for stress-associated sigma factors and amino acid biosynthesis and inhibiting the transcription of stable RNAs (rRNA and tRNA) [23].

Figure 1.

The (p)ppGpp-mediated stringent response. (A) Low amino acid concentrations lead to decreased charging of the corresponding tRNAs. (B) The translational machinery depends on the translocation along the mRNA whereby a new acetylated-tRNA is positioned in the ribosome. Whenever an uncharged tRNA binds to the ribosome, the elongation of the polypeptide chain is stalled. (C) The stringent factor RelA is then activated in the presence of the ribosomal protein L11, catalyzing the synthesis of (p)ppGpp nucleotides. (D) These nucleotides bind directly to the RNA polymerase and affect the binding abilities of sigma factors to the core RNA polymerase. (E) The cofactor DksA also binds to the RNA polymerase and augments the (p)ppGpp regulation of the transcription initiation at certain σ70-dependent promoters, functioning both as negative and positive regulators. (F) These regulators change the gene expression: (i) decreasing the transcription activity of genes involved in translational activities; (ii) and increasing the transcription of stress-related operons and genes encoding for enzymes needed for the synthesis and the transport of amino acids.

This (p)ppGpp-mediated scenario is quite complex and many fundamental details remain uncertain, such as the mechanisms underlying the activation of transcription by (p)ppGpp [24,25] or the global effects of activating/inhibiting certain stress-related genes [26,27]. To be able to systematically identify and collect information on the main components of the stringent response a semi-automatic literature review process was implemented. We propose the application of a literature mining approach that, besides complementing manual literature review, takes advantage of public database information and ontology assignments to provide for large-scale enrichment and contextualisation of textual evidences. The literature mining approach aimed at (i) corroborating existing knowledge about key players and the processes in which they are involved during the stringent response of E. coli and (ii) unveiling knowledge that has been overlooked in the up to date reviews.

Results

The investigation of the stringent response involved the search for three main biological classes: genetic components (genes, RNA and DNA molecules), gene products (proteins, transcription factors and enzymes) and small molecules. These classes cover for most of the relevant biological concepts involved in this response and each biological concept can be associated with one or more variant names. The annotation of these concepts refers to the mark-up of textual contents that match one of those names.

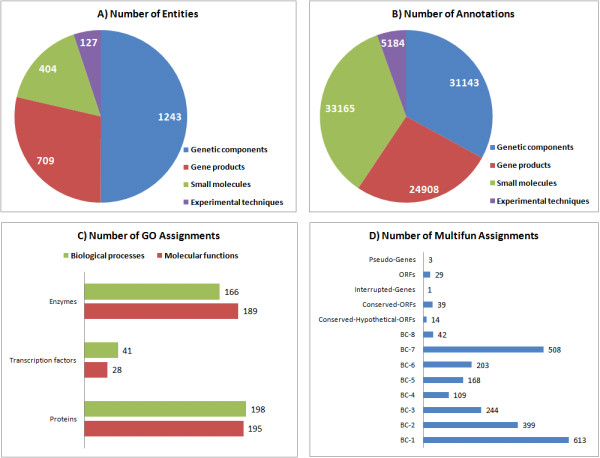

In the applied literature mining approach, full-text documents related to the stringent response of E. coli (published till 2009) were retrieved using NCBI PubMed tools and were further processed to automatically identify and annotate biological concepts in the text. Since we were looking for a wide range of biological concepts, the examination of full-texts was expected to bring much more information. Therefore, the search was limited to documents with link to full-texts. From a total of 251 documents, only 193 full-text documents comprise the corpus in this study, due to the availability of links to full text articles in PubMed and institutional journal subscriptions (see Additional file 1). EcoCyc database [28], a key resource for E. coli studies, provided for most of the controlled vocabulary used for the annotation of relevant entities in the documents, namely genes, gene products and small molecules. Proteomics Standards Initiative-Molecular Interactions (PSI-MI) ontology [29] supported the annotation of experimental techniques. After manual curation, i.e. a process to refine and correct annotations, the corpus consisted of 93893 annotations for 2474 biological concepts that were distributed as follows (see Figure 2): genetic components and small molecules accounted for the largest number of annotations (33% and 35% of the overall number of annotations, respectively) and almost half of the biological concepts annotated in full-text documents were classified as genetic components. Additionally, assignments of annotated concepts to MultiFun ontology [30] and Gene Ontology (GO) [31] enabled the identification of biological processes and molecular functions, which were distributed as follows (see Figure 2): enzymes and proteins contributed to most GO assignments; and the MultiFun cellular function categories 'Metabolism'(BC-1) and 'Location of gene products' (BC-7) related to most of the annotated genes. Details are given in Additional file 2.

Figure 2.

Corpus annotation contents. Overview of the extent of biological concepts (A) and concept annotations (B) per class in the corpus. GO assignments (C) for molecular functions and biological processes mapped for each set of gene products (i.e. enzymes, transcription factors and other proteins) and MultiFun gene assignments (D) for different functional roles (BC-1 to Metabolism, BC-2 to Information transfer, BC-3 to Regulation, BC-4 to Transport, BC-5 to Cell processes, BC-6 to Cell structure, BC-7 to Location of gene products and BC-8 to Extrachromosomal origin) were recognized in the corpus.

The analysis of the corpus was based on the assumption that relevant entities could be identified by finding frequent concepts in documents. As such, we measured the frequency of concepts (freqti) and the mean (meanti) and the standard deviation (stdti) of the annotations to evaluate their relevance in the discussion throughout the corpus. In other words, the concept frequency (freqti) estimated the fraction of documents where a concept was annotated, while the mean (meanti) and standard deviation (stdti) of concept annotations evaluated the distribution of annotations over the corpus. A concept that shows high frequency in the corpus and is annotated more than once per document is likely to have some relevance in the stringent response. To further attest this assumption, we have estimated the variance-to-mean ratio (VMRti) that measures the dispersion of annotations for each concept, indicating the existence of document clusters.

We have additionally estimated the frequency of co-annotation (freqti, tj) of two concepts, i.e. the number of documents in which concepts ti and tj co-occur within the corpus. Co-occurrence analyses has been previously used to establish relationships between biomedical concepts from literature, such as genes and pathways [2,32]. Here we expected to identify pairs of concepts that co-occur frequently in documents, assuming that this frequency is an indication of some sort of relationship between the two concepts and related to the stringent response. Further analyses were performed to evaluate concept annotations per decade, which allowed us to understand the evolving of the topic throughout the years and, in particular, the impact of technology-driven advances. At last, functional enrichment analysis was performed to evaluate which ontology terms were most assigned to annotated concepts. In this analysis we have only considered MultiFun and GO terms related with molecular functions and biological processes, respectively. These results will be detailed in the next subsections.

Biological concepts

The analysis of the frequency of annotated genetic components (see Table 1) evidenced that entities like the relA gene and the RNA and DNA molecules were annotated in more than 70% of the documents. Though the representativeness of such entities in these documents was considerably high (i.e. high mean of annotation), the annotations were over-dispersed (VMR > 1). For example, the relA gene has a mean of over 22 annotations per document and a VMR of over 33, meaning that some documents present a very high number of annotations, while others rarely mention that gene. This suggests that only a small part of the documents are focused on the discussion of this gene in the stringent response and those are probably the most relevant considering the characterization of its role in this cellular process.

Table 1.

Annotations of the genetic components in the corpus.

| Class | Concept | Number of Annotations | Number of Documents | % Frequency (Eq. 1)ψ | Mean (Eq. 2) | Std (Eq. 3) | VMR (Eq. 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genes | relA | 3163 | 138 | 71.50 | 22.92 | 27.23 | 33.14 |

| spoT | 1315 | 88 | 45.60 | 14.94 | 27.42 | 52.07 | |

| lac | 354 | 63 | 32.64 | 5.620 | 19.42 | 72.20 | |

| lacZ | 534 | 50 | 25.91 | 10.68 | 17.16 | 28.90 | |

| thi | 91 | 47 | 24.35 | 1.940 | 0.050 | 4.000 | |

| rel | 523 | 47 | 24.35 | 11.13 | 20.68 | 36.36 | |

| recA | 82 | 39 | 20.21 | 2.100 | 1.810 | 0.5000 | |

| rpsL | 95 | 36 | 18.65 | 2.640 | 3.530 | 4.500 | |

| thr | 84 | 36 | 18.65 | 2.330 | 3.760 | 4.500 | |

| rpsG | 103 | 34 | 17.62 | 3.030 | 7.250 | 16.33 | |

| leu | 98 | 34 | 17.62 | 2.880 | 6.800 | 18.00 | |

| rpoS | 205 | 33 | 17.10 | 6.210 | 10.83 | 16.67 | |

| kan | 308 | 33 | 17.10 | 9.330 | 16.61 | 28.44 | |

| glnV | 42 | 31 | 16.06 | 1.350 | 0.7400 | 0 | |

| rpoB | 389 | 30 | 15.54 | 12.97 | 17.60 | 24.08 | |

| ptsG | 240 | 30 | 15.54 | 8.000 | 21.54 | 55.13 | |

| trp | 144 | 25 | 12.95 | 5.760 | 14.73 | 39.20 | |

| carA | 60 | 20 | 10.36 | 3.000 | 3.810 | 3.000 | |

| hsdR | 23 | 19 | 9.840 | 1.210 | 0.5600 | 0 | |

| DNAs | DNA | 1839 | 137 | 70.98 | 13.42 | 16.31 | 19.69 |

| plasmid DNA | 193 | 36 | 18.65 | 5.360 | 12.31 | 28.80 | |

| chromosomal DNA | 63 | 24 | 12.44 | 2.630 | 2.440 | 2.000 | |

| cDNA | 125 | 23 | 11.92 | 5.430 | 5.820 | 5.000 | |

| RNAs | RNA | 4193 | 140 | 72.54 | 29.95 | 38.21 | 49.79 |

| uncharged tRNA | 1168 | 117 | 60.62 | 9.980 | 19.64 | 40.11 | |

| rRNA | 1116 | 97 | 50.26 | 11.51 | 25.97 | 56.82 | |

| a mRNA | 999 | 91 | 47.15 | 10.98 | 19.52 | 36.10 | |

| rrnA | 911 | 87 | 45.08 | 10.47 | 22.51 | 48.40 | |

| stable RNA | 430 | 87 | 45.08 | 4.940 | 8.030 | 16.00 | |

| a charged tRNA | 140 | 43 | 22.28 | 3.260 | 4.200 | 5.330 | |

| rrnB | 301 | 26 | 13.47 | 11.58 | 19.30 | 32.82 | |

| rrn | 321 | 26 | 13.47 | 12.35 | 30.42 | 75.00 | |

| 16s-rRNAs | 156 | 25 | 12.95 | 6.240 | 9.090 | 13.50 | |

Individual genetic components (i.e. genes, DNAs and RNAs) were evaluated considering the number of documents where these entities were annotated and their number of annotations in the corpus. Statistical measurements are detailed in the Methods and Materials section.

ψ A threshold of 10% of the frequency of annotation was set for each genetic component category. However, lists of all annotated entities are provided in Additional file 5.

VMR: variance-to-mean

Std: standard deviation

Similarly, the analysis of gene product annotations (see Table 2) exposed RelA, RNAP and ribosomes as highly annotated entities (present in over than 50% of the documents) with a considerable degree of over-dispersion (VMR > 1). It was interesting to verify that the Fis transcriptional dual regulator, which modulates several cellular processes, such as the transcription of stable RNA (PMID: 2209559; PMID: 9973355)1 [33-35], was highly annotated (with a mean of almost 50 annotations per document), but presented a low frequency (less than 10% of the documents). The extreme value of VMR (over 150) pointed out that some of these documents are devoted to the discussion of this biological entity, which contributed to the large annotation of this concept.

Table 2.

Annotations of the gene products in the corpus.

| Class | Concept | Number of Annotations | Number of Documents | % Frequency (Eq. 1)ψ | Mean (Eq. 2) | Std (Eq. 3) | VMR (Eq. 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins | Ribosome | 1643 | 128 | 66.32 | 12.84 | 23.57 | 44.08 |

| Rel | 1021 | 62 | 32.12 | 16.50 | 36.60 | 81.00 | |

| LacZ | 543 | 53 | 27.46 | 10.30 | 17.44 | 28.90 | |

| Sigma 38 factor | 392 | 42 | 21.76 | 9.330 | 15.40 | 25.00 | |

| Sigma factor | 112 | 35 | 18.13 | 3.200 | 5.870 | 8.330 | |

| UvrD | 56 | 35 | 18.13 | 1.600 | 1.300 | 1.000 | |

| RpoB | 252 | 35 | 18.13 | 7.200 | 11.50 | 17.29 | |

| RecA | 99 | 31 | 16.06 | 3.190 | 4.260 | 5.330 | |

| EF-Tu | 223 | 26 | 13.47 | 8.580 | 17.32 | 36.13 | |

| Der | 51 | 25 | 12.95 | 2.040 | 2.140 | 2.000 | |

| Sigma 70 factor | 134 | 21 | 10.88 | 6.380 | 11.19 | 20.17 | |

| Transcription factors | Fis | 888 | 18 | 9.330 | 49.33 | 86.88 | 150.9 |

| Fur | 56 | 13 | 6.740 | 4.310 | 9.260 | 20.25 | |

| CRP | 279 | 12 | 6.220 | 23.25 | 36.28 | 56.35 | |

| DnaA | 121 | 11 | 5.700 | 11.00 | 23.00 | 48.09 | |

| H-NS | 73 | 11 | 5.700 | 6.640 | 10.73 | 16.67 | |

| LexA | 101 | 10 | 5.180 | 10.10 | 18.32 | 32.40 | |

| IHF | 54 | 9 | 4.660 | 6.000 | 5.250 | 4.170 | |

| Enzymes | RelA | 4138 | 152 | 78.76 | 27.22 | 31.16 | 35.59 |

| RNAP | 1873 | 117 | 60.62 | 16.01 | 28.08 | 49.00 | |

| SpoT | 1024 | 60 | 31.09 | 17.07 | 42.19 | 103.8 | |

| EcoRI | 215 | 53 | 27.46 | 4.060 | 4.970 | 4.000 | |

| β-galactosidase | 294 | 47 | 24.35 | 6.260 | 6.550 | 6.000 | |

| BamHI | 149 | 43 | 22.28 | 3.470 | 5.870 | 8.330 | |

| HindIII | 114 | 41 | 21.24 | 2.780 | 2.160 | 2.000 | |

| RNase | 109 | 36 | 18.65 | 3.030 | 4.280 | 5.330 | |

| YbcS | 50 | 23 | 11.92 | 2.170 | 2.620 | 2.000 | |

| Reverse transcriptase | 34 | 21 | 10.88 | 1.620 | 1.050 | 1.000 | |

| tRNA synthetase | 54 | 20 | 10.36 | 2.700 | 2.630 | 2.000 | |

| Endonuclease I | 29 | 20 | 10.36 | 1.450 | 1.400 | 1.000 | |

Individual gene products (i.e. enzymes, transcription factors and other proteins) were evaluated considering the number of documents where these entities were annotated and their number of annotations in the corpus. Statistical measurements are detailed in the Methods and Materials section.

ψ A threshold of 10% of the frequency of annotation was set for enzymes and other proteins, whereas a threshold of 5% was set for transcription factors. However, lists of all annotated entities are provided in Additional file 6.

VMR: variance-to-mean

Std: standard deviation

The analysis of the annotation of small molecules (see Table 3) revealed that, though almost 83% of the documents discussed the general role of amino acids and nucleotides, the mean of annotation of specific nucleotides and amino acids was quite low (less than 10 annotations per document in most cases). The two exceptions were the nucleotides ppGpp and (p)ppGpp (the collective reference for ppGpp and pppGpp). A high frequency (75% and 37%, respectively) and mean of annotation (29 and 43, respectively) confirm that these nucleotides are central in the stringent response in E. coli. Indeed, during amino acid starvation (p)ppGpp nucleotides coordinate several cellular activities by influencing gene expression.

Table 3.

Annotations of the small molecules in the corpus.

| Concept | Number of Annotations | Number of Documents | % Frequency of annotation (Eq. 1)ψ | Mean of annotation (Eq. 2) | Std (Eq. 3) | VMR (Eq. 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino acids | 1557 | 160 | 82.90 | 9.730 | 13.83 | 18.78 |

| Nucleotides | 1230 | 145 | 75.13 | 8.480 | 9.290 | 10.13 |

| ppGpp | 4159 | 145 | 75.13 | 28.68 | 31.00 | 34.32 |

| β-D-glucose | 792 | 123 | 63.73 | 6.440 | 10.63 | 16.67 |

| Pi | 662 | 113 | 58.55 | 5.860 | 12.60 | 28.80 |

| Guanosine | 407 | 112 | 58.03 | 3.630 | 3.540 | 3.000 |

| ATP | 587 | 100 | 51.81 | 5.870 | 7.410 | 9.800 |

| GTP | 748 | 91 | 47.15 | 8.220 | 13.85 | 21.13 |

| AMP | 598 | 90 | 46.63 | 6.640 | 10.09 | 16.67 |

| PPi | 447 | 87 | 45.08 | 5.140 | 5.180 | 5.000 |

| H2O | 210 | 83 | 43.01 | 2.530 | 2.430 | 2.000 |

| Tris | 261 | 82 | 42.49 | 3.180 | 2.800 | 1.330 |

| Carbon | 288 | 80 | 41.45 | 3.600 | 4.850 | 5.330 |

| Chloramphenicol | 435 | 77 | 39.90 | 5.650 | 8.250 | 12.80 |

| pppGpp | 632 | 74 | 38.34 | 8.540 | 13.61 | 21.13 |

| (p)ppGpp | 3127 | 72 | 37.31 | 43.43 | 56.00 | 72.93 |

| NaCl | 189 | 67 | 34.72 | 2.820 | 2.790 | 2.000 |

| L-lactate | 413 | 65 | 33.68 | 6.350 | 20.84 | 66.67 |

| Glycerol | 145 | 65 | 33.68 | 2.230 | 1.850 | 0.5000 |

| Ethanol | 189 | 65 | 33.68 | 2.910 | 4.400 | 8.000 |

| Na+ | 145 | 63 | 32.64 | 2.300 | 2.100 | 2.000 |

| Ampicillin | 321 | 62 | 32.12 | 5.180 | 12.74 | 28.80 |

| EDTA | 142 | 60 | 31.09 | 2.370 | 1.680 | 0.5000 |

| L-methionine | 248 | 59 | 30.57 | 4.200 | 6.670 | 9.000 |

| L-histidine | 183 | 59 | 30.57 | 3.100 | 5.410 | 8.330 |

| L-valine | 396 | 57 | 29.53 | 6.950 | 11.90 | 20.17 |

| Formate | 136 | 57 | 29.53 | 2.390 | 2.360 | 2.000 |

Individual small molecules were evaluated considering the number of documents where these entities were annotated and the number of annotations in the corpus. Statistical measurements are detailed in the Methods and Materials section.

ψ A threshold of 30% of the frequency of annotation was set for compounds. However, lists of all annotated entities are provided in Additional file 7.

VMR: variance-to-mean

Std: standard deviation

Taking these results into account, the frequency of co-annotation of these nucleotides with gene products was evaluated. As mentioned above, it can be admitted that the co-occurrence of two concepts (ti and tj) in the same body text might indicate a relationship between them (even if indirect). Thus, to find key players in the stringent response that are possibly affected by the accumulation of (p)ppGpp nucleotides, the frequency of co-annotation of concepts for gene products and each of these nucleotides was estimated. As shown in Figure 3 and Additional file 3, (p)ppGpp nucleotides were found to be considerably co-annotated with highly representative proteins, namely: the RelA and SpoT enzymes that control the basal levels of the nucleotides (in 93% and 67% of the (p)ppGpp-annotated documents, respectively); ribosomes that are affected by the nucleotides activity (in approximately 79% of the (p)ppGpp-annotated documents); RNAP (in approximately 64% of the (p)ppGpp-annotated documents); and the RpoS, the alternative sigma factor σ38 that acts as the master regulator of the general stress response (in approximately 40% of the (p)ppGpp-mentioning documents) (PMID: 9326588) [35]. Some proteins were co-annotated with only one or two of the concepts. For instance, the Gpp enzyme that converts pppGpp into ppGpp (PMID: 8531889; PMID: 6130093) [36,37] was essentially co-annotated with the pppGpp concept. In turn, the RecA protein, which catalyses DNA strand exchange reactions (PMID: 17590232) [38], and the tRNA synthetase were co-annotated with (p)ppGpp and ppGpp with a frequency higher than 10%, whereas other proteins were mainly co-annotated with (p)ppGpp and pppGpp: the elongation factor (EF) G, known to facilitate the translocation of the ribosome along the mRNA molecules (PMID: 8531889) [36]; the RplK (or 50S ribosomal subunit protein L11) that was reported to be essential when the 30S ribosomal initiation complex joins to the 50S ribosomal subunit and in the EF-G-dependent GTPase activity (PMID: 17095013; PMID: 12419222) [39,40]; and the enzyme PhoA known to be involved in the acquisition and transport of phosphate (PMID: 9555903) [41].

Figure 3.

Proteins co-annotated with ppGpp, pppGpp and the collective (p)ppGpp entities. The nodes represent proteins with frequency of co-annotation higher than 10%. Highly co-annotated proteins are represented by nodes with a larger size (frequencies of co-annotation greater than 50%). Pink nodes represent the proteins that were co-annotated with the three entities, while green and yellow nodes indicate the proteins that were co-annotated with only two and one of the nucleotides, respectively.

Additionally, results pointed out potentially interesting associations with less represented proteins (see Additional file 3), such as: the Fur transcriptional activator that controls the transcription of genes involved in iron homeostasis (PMID: 15853883) [42]; the HN-S transcriptional dual regulator that is capable of condensing and supercoiling DNA (PMID: 10966109) [43]; the DnaA protein implicated in the chromosomal replication initiation (PMID:1690706) [44]; the DinJ-YafQ complex involved in the inhibition of protein synthesis and growth (PMID:12123445) [12] and the MazE antitoxin of the MazF-MazE toxin-antitoxin system involved in translation inhibition processes (PMID:12123445) [12]. In general, most co-annotated entities correspond to gene products that have regulatory functions in the gene transcription process, such as transcriptional factors, or that are components of the translational apparatus.

Examining less-reported entities

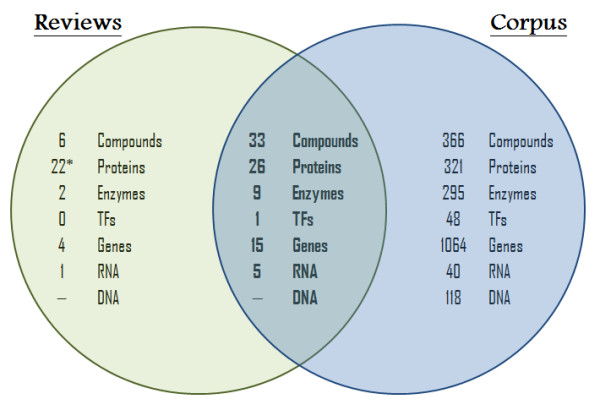

In the present corpus, most of the biological entities identified as major participants in the E. coli stringent response, were also extensively cited in recent reviews [9,11,17,24,25] (see Additional file 4). These reviews were selected based on their relevance in terms of information specifically collected for the stringent response in E. coli and their number of citations. As illustrated in Figure 4, biological concepts considered to be key components in those reviews were also evidenced by the semi-automatic information extraction approach.

Figure 4.

Venn diagram comparing annotations from corpus and selected reviews. This diagram indicates the number of biological concepts per class that represent the corpus and from the latest reviews considered to be relevant to this subject. The intersecting zone gives the number of biological concepts that were simultaneously reported in the two set of documents.

However, when examining the extent of annotated concepts from the selected reviews and the corpus, it was evident that many biological entities have been disregarded or less reported in the reviews. Biological entities, such as transcriptional factors and other gene products like stress-related proteins, were not described in the selected reviews. Indeed, often the role of some biological entities that are directly (or indirectly) associated with the stringent response, is missing in most literature revisions. To illustrate this, we compiled information on the participation of some less-reported biological entities in E. coli stringent response by validating their role. These results can be found in Table 4.

Table 4.

Some examples of less-reported entities (namely in recent reviews), which are relevant in the E. coli stringent response.

| Biological entities | Freq (%) | Details | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| DnaJ - chaperone with DnaK | 3.11 | Chaperone protein that assists the DnaJ/DnaK/GrpE system of E. coli. The overproduction of ppGpp has shown to induce the accumulation of these chaperones. | [68] |

| ClpB chaperone | 1.55 | ClpB, together with the DnaJ/DnaK/GrpE chaperone system, is able to resolubilize aggregated proteins. | [69] |

| GroEL-GroES chaperonin complex | 0.52 | GroEL and GroES are both induced by heat and when ppGpp is overproduced in E. coli. | [68] |

| RuvB - branch migration of Holliday structures; repair helicase | 1.55 | Component of the RuvABC enzymatic complex that promotes the rescue of stalled (often formed by ppGpp) or broken DNA replication forks in E. coli. | [70] |

| CsrA - carbon storage regulator | 1.04 | Regulator of carbohydrate metabolism, which activates UvrY, responsible for the transcription of csrB that, in turn, inhibits the CsrA activity. | [71] |

| uvrY | 0.52 | Encodes the UvrY protein that has been shown to be the cognate response regulator for the BarA sensor protein. This regulator participates in controlling several genes involved in the DNA repair system (e.g. CsrA) and carbon metabolism. | [72] |

| cstA | 0.52 | Gene encoding the CstA peptide transporter, which expression is induced by carbon starvation and requires the CRP-cAMP transcriptional regulator. The CstA translation is regulated by the CsrA that occludes ribosome binding to the cstA mRNA. | [73] |

| CspD - DNA replication inhibitor | 0.52 | CspD is a toxin that appears to inhibit the DNA replication. ppGpp is one of the positive factors for the expression of cspD. | [74] |

| FabH - β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase III | 0.52 | A key enzyme in the initiation of fatty acids biosynthesis that is stringently regulated by ppGpp. | [75] |

| FadR transcriptional dual regulator | 1.55 | Regulates the fatty acid biosynthesis and fatty acid degradation at the level of transcription. ppGpp has been shown to be also involved in the regulation of these pathways | [75] |

| NtrC-Phosphorylated transcriptional dual regulator | 1.04 | Regulatory protein involved in the assimilation of nitrogen and in slow growth caused by N-limited condition. It was reported that ppGpp levels increase upon nitrogen starvation. | [76] |

| dps | 2.59 | Gene encoding the Dps protein that is highly abundant in the stationary-phase and is required for the starvation responses. It was found to be regulated by ppGpp and RpoS. | [77,78] |

| psiF | 2.07 | Gene induced during phosphate starvation that has been associated with the accumulation of ppGpp. | [41] |

| chpR | 2.07 | Encodes the MazE antitoxin, a component of the MazE-MazF system that causes a "programmed cell death" in response to stresses, including starvation. Genes mazE and mazF are located in the E. coli rel operon and are regulated by ppGpp. | [79] |

| mazG | 0.52 | Encodes the MazG nucleoside pyrophosphohydrolase that limits the detrimental effects of the MazF toxin under nutritional stress conditions. Overexpression of mazG inhibits cell growth and negatively affects accumulation of ppGpp. | [80] |

The recognition of these proteins in the corpus was invaluable, allowing to uncover various stress-responsive proteins, such as chaperones (e.g. DnaJ, ClpB or the GroEL-GroES chaperonin complex) and toxin-antitoxin systems (e.g. protein encoded by chpR) that are normally associated with other stress responses. The description of such entities as participants in the stringent response discloses a more insightful overview of the complexity of these entangled cellular processes. For example, the identification of entities related to certain metabolic pathways, like the fatty acids biosynthesis (e.g. FabH and FabR), or DNA processes, like DNA replication (e.g. CspD) and DNA repair (e.g. uvrY), can expand the characterization of stringently regulated activities that have not been evident in previous reviews.

Evolution of technology versus knowledge

From the previous results it is clear that studies on the stringent response were essentially focused on the characterizations of the catalytic activities of the enzymes RelA and SpoT and their role in the control of (p)ppGpp accumulation. Though these processes are central in the stringent response, the global effects of the (p)ppGpp-dependent response are of primordial importance. The influence on transcription and translation processes and the triggering of other stress responses have raised interest from researchers.

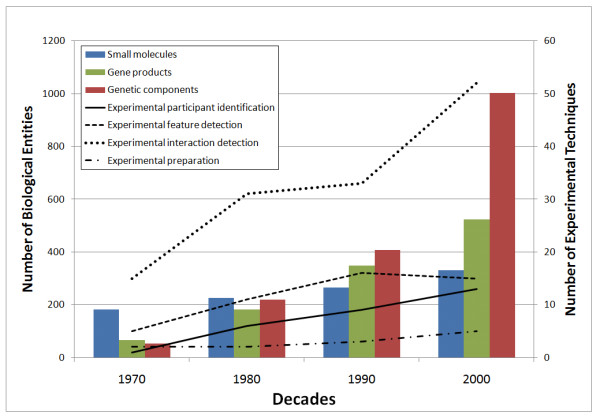

As such, the investigation of many other biological entities and their roles during the stringent response has driven research to the systems-wide understanding of this complex regulatory networks [12]. Only with the development of more sophisticated techniques, like peptide mass fingerprinting (MI:0082) or chromatin immunoprecipitation arrays (MI:0225), it was possible to investigate the complexity of biological systems in a high throughput manner. The development of experimental techniques was a key point in this transition and it is expected to intersect points of turnover on the study of the stringent response. We could confirm that with the availability of more experimental techniques, the extent of biological concepts annotated in our corpus increased. By comparing the number of annotations of biological concepts (genetic components, gene products and small molecules) and experimental techniques (grouped into major PSI-MI classes) per decade (Figure 5) it is possible to verify the progression of knowledge related with the stringent response in E. coli.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the expansion of knowledge to the applied experimental techniques. Bars represent the number of biological entities (left Y axis) found for the three major biological classes, i.e., genetic components (genes, RNAs and DNAs), gene products (proteins, transcription factors and enzymes) and small molecules. Lines plot the number of experimental techniques (right Y axis) associated to the annotated PSI-MI classes.

The analysis evidenced that the repertoire of experimental techniques has been growing significantly and the study is ever more dedicated to the investigation of genetic components. In particular, results showed the use of an ever-growing number of experimental interaction detection methods (MI:0045) and a considerable number of experimental participant identification (MI:0661) and experimental feature detection (MI:0659) methods. The analysis of annotated experimental techniques in the corpus (Table 5) evidenced that the chromatography technology (MI:0091), experimental feature detection (MI:0657), genetic interference (MI:0254) and primer specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (MI:0088) techniques were annotated in more than 40% of the documents. Most techniques were referred roughly two times per document, but primer-specific PCR (MI:0088) and array technology (MI:0008) presented a considerable mean of annotation (with over 10 and 8 annotations per document, respectively) and high VMR values (22.5 and 6.13, respectively), which indicated that these techniques were essentially discussed in a given set of documents.

Table 5.

PSI-MI assignments to annotated experimental techniques.

| Techniques | Statistics over the corpus | Frequency per Decade | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSI-MI Class | PSI-MI id | PSI-MI name | Freq | Mean | Std | VMR | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 |

| MI:0659 experimental feature detection | MI:0659 | experimental feature detection* | 55% | 2.44 | 2.76 | 2 | 64% | 65% | 67% | 67% |

| MI:0833 | autoradiography | 25% | 1.65 | 1.4 | 1 | 29% | 35% | 22% | 22% | |

| MI:0113 | western blot | 21% | 4.95 | 3.38 | 2.25 | - | 13% | 18% | 44% | |

| MI:0074 | mutation analysis | 20% | 3.34 | 3.24 | 3 | 14% | 20% | 27% | 32% | |

| MI:0114 | x-ray crystallography | 4% | 1.63 | 1.46 | 1 | - | - | 2% | 8% | |

| MI:0811 | insertion analysis | 4% | 1.14 | 0.38 | 0 | - | - | 7% | 4% | |

| MI:0045 experimental interaction detection | MI:0091 | chromatography technology | 50% | 4.23 | 4.14 | 4 | 100% | 85% | 55% | 64% |

| MI:0254 | genetic interference | 42% | 2.68 | 2.35 | 2 | - | 28% | 69% | 64% | |

| MI:0807 | comigration in gel electrophoresis | 37% | 2.51 | 2.13 | 2 | 21% | 48% | 51% | 49% | |

| MI:0045 | experimental interaction detection* | 36% | 3.1 | 3.12 | 3 | 14% | 45% | 47% | 41% | |

| MI:0808 | comigration in sds page | 27% | 2.02 | 1.61 | 0.5 | 7% | 23% | 33% | 29% | |

| MI:0099 | scintillation proximity assay | 24% | 1.94 | 1.65 | 1 | 64% | 35% | 20% | 15% | |

| MI:0051 | fluorescence technology | 16% | 1.84 | 1.8 | 1 | 7% | 20% | 5% | 22% | |

| MI:0071 | molecular sieving | 15% | 2.25 | 3.19 | 4.5 | 29% | 13% | 15% | 13% | |

| MI:0217 | phosphorylation reaction | 13% | 2.72 | 3.74 | 4.5 | 7% | 8% | 16% | 14% | |

| MI:0415 | enzymatic study | 12% | 1.96 | 2.11 | 4 | 7% | 8% | 11% | 19% | |

| MI:0008 | array technology | 10% | 8.47 | 7.47 | 6.13 | - | - | - | 22% | |

| MI:0928 | filter trap assay | 9% | 2.24 | 2.47 | 2 | 36% | 13% | 4% | 6% | |

| MI:0004 | affinity chromatography technology | 8% | 2.33 | 2.44 | 2 | - | 5% | 5% | 13% | |

| MI:0428 | imaging technique | 7% | 1.57 | 1.41 | 1 | - | 8% | 4% | 11% | |

| MI:0047 | far western blotting | 6% | 1.5 | 0.82 | 0 | - | 3% | 7% | 8% | |

| MI:0435 | protease assay | 6% | 3.92 | 4.01 | 5.33 | - | 5% | 5% | 8% | |

| MI:0017 | classical fluorescence spectroscopy | 6% | 1.08 | 0.29 | 0 | - | - | 5% | 11% | |

| MI:0089 | protein array | 6% | 1.64 | 1.62 | 1 | - | 3% | 2% | 11% | |

| MI:0029 | cosedimentation through density gradient | 5% | 5.22 | 3.94 | 1.8 | 43% | 10% | - | 2% | |

| MI:0040 | electron microscopy | 4% | 2.57 | 1.31 | 0.5 | - | 10% | - | 4% | |

| MI:0676 | tandem affinity purification | 3% | 3.8 | 5.18 | 8.33 | - | - | - | 7% | |

| MI:0054 | fluorescence-activated cell sorting | 3% | 5.8 | 4.6 | 3.2 | - | - | 4% | 4% | |

| MI:0413 | electrophoretic mobility shift assay | 3% | 1.6 | 0.77 | 0 | - | - | 5% | 2% | |

| MI:0012 | bioluminescence resonance energy transfer | 2% | 6.25 | 5.68 | 4.17 | - | - | 4% | 2% | |

| MI:0018 | two hybrid | 2% | 2 | 1.41 | 0.5 | - | - | - | 7% | |

| MI:0053 | fluorescence polarization spectroscopy | 2% | 5 | 2.94 | 0.8 | - | 3% | - | 2% | |

| MI:0397 | two hybrid array | 2% | 2 | 1.41 | 0.5 | - | - | 2% | 2% | |

| MI:0227 | reverse phase chromatography | 2% | 3.25 | 2.87 | 1.33 | - | - | 5% | 1% | |

| MI:0226 | ion exchange chromatography | 1% | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | 1% | |

| MI:0031 | protein cross-linking with a bifunctional reagent | 1% | 7 | 4 | 2.29 | - | 3% | - | 1% | |

| MI:0052 | fluorescence correlation spectroscopy | 1% | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | 1% | |

| MI:0416 | fluorescence microscopy | 1% | 2.5 | 0.71 | 0 | - | - | - | 2% | |

| MI:0016 | circular dichroism | 1% | 1.5 | 0.71 | 0 | - | - | - | 2% | |

| MI:0225 | chromatin immunoprecipitation array | 1% | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | 1% | |

| MI:0872 | atomic force microscopy | 1% | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | 1% | |

| MI:0049 | filter binding | 1% | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | 3% | 2% | - | |

| MI:0426 | light microscopy | 1% | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | 2% | |

| MI:0661 experimental participant identification | MI:0088 | primer specific pcr | 40% | 10.38 | 15.87 | 22.5 | - | 8% | 29% | 95% |

| MI:0080 | partial dna sequence identification by hybridization | 27% | 3.75 | 3.47 | 3 | 14% | 30% | 29% | 26% | |

| MI:0078 | nucleotide sequence identification | 20% | 1.77 | 1.26 | 1 | - | 15% | 25% | 22% | |

| MI:0103 | southern blot | 14% | 3.04 | 2.05 | 1.33 | - | 8% | 15% | 19% | |

| MI:0929 | nothern blot | 8% | 5.56 | 4.8 | 3.2 | - | 3% | 11% | 11% | |

| MI:0421 | identification by antibody | 6% | 1.82 | 1.51 | 1 | - | 8% | 5% | 6% | |

| MI:0427 | identification by mass spectrometry | 5% | 1.67 | 0.94 | 0 | - | - | 4% | 8% | |

| MI:0082 | peptide massfingerprinting | 2% | 1.5 | 0.71 | 0 | - | - | - | 5% | |

| MI:0093 | protein sequence identification | 1% | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | - | 2% | ||

| MI:0411 | enzyme linked immunosorbent assay | 1% | 4 | 2 | 1 | - | - | 2% | 1% | |

| MI:0346 experimental preparation | MI:0714 | nucleic acid transduction | 26% | 2.22 | 2.82 | 2 | 14% | 15% | 31% | 29% |

| MI:0715 | nucleic acid conjugation | 6% | 1.73 | 1.41 | 1 | 7% | 3% | 5% | 7% | |

| MI:0308 | electroporation | 5% | 1.89 | 1.56 | 1 | - | - | 2% | 9% | |

| MI:0343 | cdna library | 3% | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | 6% | |

| MI:0190 interaction type | MI:0194 | cleavage reaction | 1% | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | 3% | - | - |

| MI:0116 feature type | MI:0373 | dye label | 5% | 1.2 | 0.45 | 0 | 7% | 8% | 5% | 4% |

Experimental techniques were evaluated considering the number of documents where these concepts were annotated and the number of annotations in the corpus. Moreover, the frequency of annotation of experimental techniques was also estimated for documents published in the four decades (from 1970 to 2009). Statistical measures are detailed in the Methods and Materials section.

* These PSI-MI general classes were used to identify techniques that did not map into any particular technique within the class.

A detailed look into the frequency of concept annotation per decade points out that some of the techniques used in early studies have a reduced application today and highlights the increasing influence of high-throughput technologies in recent studies. For instance, experimental interaction detection methods (MI:0045), such as the scintillation proximity assay (MI:0099), the molecular sieving (MI:0071), the filter trap assays (MI:0928) and the cosedimentation through density gradient (MI:0029) were mostly annotated in documents from the first decade (1970-1980), whereas the comigration in gel electrophoresis (MI:0807) and enzymatic studies (MI:0415) were increasingly reported in documents throughout the decades.

Functional enrichment

Recent developments in the functional annotation of genomes using biological ontologies provided the means to contextualise literature mining outputs. The automatic mapping of annotated concepts to ontology terms was facilitated by EcoCyc database information that supports the assignment of MultiFun and GO ontology terms to genes and gene products. MultiFun ontology classifies gene products according to their cellular function, namely: metabolism, information transfer, regulation, transport, cell processes, cell structure, location, extra-chromosomal origin, DNA site, and cryptic gene. In turn, GO embraces three separate ontologies: cellular components, i.e. the parts of a cell or its extracellular environment; molecular functions, i.e. the basic activities of a gene product at the molecular level, such as binding or catalysis; and biological processes, i.e. the set of molecular events related to the integrated functioning of cells, tissues, organs or organisms.

Here, we have analysed the assignments for MultiFun cellular functions and GO biological processes (Table 6 and Table 7). The aim was to find statistically overrepresented ontology terms related with cellular functions and biological processes within the set of annotated concepts. Seemingly to what is proposed in some bioinformatics tools [45,46], where gene expression datasets are analysed to find statistically over- or under-represented terms, we have estimated the frequency of ontology terms assigned to annotated concepts in the corpus (regarding both gene and gene products). For calculating this frequency of assignment, the fraction of documents in the corpus that included those ontology terms was also considered. For example, if a GO term is assigned to one or more concepts that altogether were annotated in 80% of the documents, than the frequency of assignment of that ontology term in the corpus is 80%.

Table 6.

MultiFun cellular function assignments.

| MultiFun Concepts | Frequency of Ontology Annotation | Brief Description | Genes | Gene Products | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Frequency of Assignment | Frequency of Annotation | Name | Frequency of Annotation | |||

| BC-1.7.33 Nucleotide and nucleoside conversions | 76% | The chemical reactions involved in the central carbon metabolism by which a nucleobase, nucleoside or nucleotide is converted from another nucleobase, nucleoside or nucleotide. | relA | 68% | 72% | RelA | 79% |

| spoT | 28% | 46% | SpoT | 31% | |||

| BC-3.1.3.4 Proteases, cleavage of compounds | 55% | Proteins that hydrolysates a peptide bond or bonds within a protein during posttranscriptional regulatory processes. | spoT | 91% | 46% | SpoT | 31% |

| BC-2.2.2 Transcription related functions | 51% | The information transfer related functions involved in the synthesis of RNA on a template of DNA. | fis | 22% | 6% | Fis | 9% |

| rpoB | 17% | 16% | RpoB | 18% | |||

| BC-2.3.2 Translation | 48% | The cellular metabolic process by which a protein is formed, using the sequence of a mature mRNA molecule to specify the sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide chain. | dksA | 23% | 3% | DksA | 8% |

| rplK | 17% | 6% | RplK | 7% | |||

| rpsG | 12% | 18% | RpsG | NA | |||

| rpsL | 11% | 19% | RpsL | 3% | |||

| BC-5.5.3 Starvation | 47% | A state or activity of a cell or an organism as a result to the adaptation to starvation. | spoT | 85% | 46% | SpoT | 31% |

| dksA | 12% | 3% | DksA | 8% | |||

| BC-1.1.1 Carbon compounds | 46% | The metabolic reactions by which living organisms utilises carbon compounds. | lacZ | 49% | 26% | LacZ | 28% |

| ptsG | 22% | 16% | PtsG | 1% | |||

| BC-2.3.8 Ribosomal proteins | 44% | Proteins that associate to form a ribosome involved in genetic information transfer in cells. | rplK | 24% | 6% | RplK | 7% |

| rpsG | 18% | 18% | RpsG | NA | |||

| rpsL | 17% | 19% | RpsL | 3% | |||

| BC-3.1.2.3 Repressor | 40% | Any transcription regulator that prevents or downregulates transcription. | fis | 41% | 6% | Fis | 9% |

| BC-3.1.2.2 Activator | 32% | Any transcription regulator that induces or upregulates transcription. | fis | 45% | 6% | Fis | 9% |

MultiFun terms were assigned to annotated concepts associated with genes. A threshold of 30% of documents was considered for ontology assignment and a threshold of 10% was used to point out the genes that most contributed to such assignment.

NA: corresponds to non-annotated gene products in the corpus.

Table 7.

GO biological processes assignments.

| Gene Ontology concepts | Frequency of Ontology Annotation | Brief Description | Gene Products | Coding Genes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Frequency of Assignment | Frequency of Annotation | Name | Frequency of Annotation | |||

| GO:0008152 Metabolic process | 89% | The chemical reactions and pathways, including anabolism and catabolism, by which living organisms transform chemical substances. | RelA | 80% | 79% | relA | 72% |

| LacZ | 10% | 24% | lacZ | 26% | |||

| GO:0015949 Nucleobase, nucleoside and nucleotide interconversion | 80% | The chemical reactions and pathways by which a nucleobase, nucleoside or nucleotide is synthesized from another nucleobase, nucleoside or nucleotide. | RelA | 80% | 79% | relA | 72% |

| SpoT | 20% | 31% | spoT | 46% | |||

| GO:0015969 Guanosine tetraphosphate metabolic process | 80% | The chemical reactions and pathways involving guanine tetraphosphate (5'-ppGpp-3'), a derivative of guanine riboside with four phosphates. | RelA | 80% | 79% | relA | 72% |

| SpoT | 20% | 31% | spoT | 46% | |||

| GO:0006350 Transcription | 56% | The synthesis of either RNA on a template of DNA or DNA on a template of RNA. | RpoS | 16% | 22% | rpoS | 17% |

| CRP | 12% | 6% | crp | 4% | |||

| RpoB | 10% | 18% | rpoB | 16% | |||

| Mfd | 10% | 2% | mfd | 2% | |||

| GO:0006355 Regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent | 52% | Any process that modulates the frequency, rate or extent of DNA-dependent transcription. | RpoS | 20% | 22% | rpoS | 17% |

| CRP | 14% | 6% | crp | 4% | |||

| Mfd | 12% | 2% | mfd | 2% | |||

| GO:0006412 Translation | 40% | The cellular metabolic process by which a protein is formed, using the sequence of a mature mRNA molecule to specify the sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide chain. | RplK | 28% | 7% | rplK | 6% |

| DksA | 28% | 8% | dksA | 3% | |||

| EF-Tu | 13% | 14% | tufB | 3% | |||

| GO:0006950 Response to stress | 39% | A change in state or activity of a cell or an organism as a result of a disturbance in cellular homeostasis, usually, but not necessarily, exogenous. | RecA | 20% | 16% | recA | 20% |

| RelB | 16% | 4% | relB | 3% | |||

| NusA | 10% | 5% | nusA | 4% | |||

| GO:0042594 Response to starvation | 39% | A change in state or activity of a cell or an organism as a result of a starvation stimulus, deprivation of nourishment. | SpoT | 67% | 31% | spoT | 46% |

| DksA | 30% | 8% | dksA | 3% | |||

| GO:0006970 Response to osmotic stress | 38% | A change in state or activity of a cell or an organism as a result of a stimulus indicating an increase or decrease in the concentration of solutes outside the organism or cell. | RpoS | 59% | 22% | rpoS | 17% |

| EF-Tu | 34% | 14% | tufB | 3% | |||

| GO:0005975 Carbohydrate metabolic process | 36% | The chemical reactions and pathways involving carbohydrates, any of a group of organic compounds based of the general formula Cx(H2O)y. | LacZ | 94% | 24% | lacZ | 26% |

| GO:0006974 Response to DNA damage stimulus | 36% | A change in state or activity of a cell or an organism as a result of a stimulus indicating damage to its DNA from environmental insults or errors during metabolism. | Mfd | 28% | 2% | mfd | 2% |

| RecA | 11% | 16% | recA | 20% | |||

| RecG | 11% | 3% | recG | NA | |||

| GO:0006281 DNA repair | 36% | The process of restoring DNA after damage that include direct reversal, base excision repair, nucleotide excision repair, photoreactivation, bypass, double-strand break repair pathway, and mismatch repair pathway. | Mfd | 28% | 2% | mfd | 2% |

| RecA | 11% | 16% | recA | 20% | |||

| RecG | 11% | 3% | recG | NA | |||

GO terms were assigned to annotated concepts associated with gene products annotations. A threshold of 35% of documents was considered for ontology assignment and a threshold of 10% was used to point out the gene products that most contributed to such assignment.

NA: corresponds to non-annotated genes in the corpus.

We have also evaluated the contribution of concept annotations to the assignment of an ontology term. The frequency of annotation of a given term (A) by a given concept (B) was therefore estimated based on the ratio of the number of annotations of the concept (B) by the number of times that ontology term (A) was assigned by any concept associated to that term (A). Since one concept can be associated to several ontology terms, it can be considered that the under- or over-representation of an ontology term can depend on the number of annotations of the assigned concepts. In this perspective, concepts that were highly annotated in the corpus were considered the most relevant for the assignment of an ontology term. In summary, we estimate which are the most important cellular processes involved in the stringent response and also the key biological concepts involved in these processes.

The analysis of MultiFun cellular function assignments (Table 6) evidenced gene functions related to central metabolism processes, post-transcriptional processes and transcription-related functions (covered by over 50% of the documents). The most assigned MultiFun cellular functions, namely metabolic functions related to nucleotide and nucleoside conversions (BC-1.7.33) and proteolytic cleavage of compounds (BC-3.1.3.4), derived from the highly annotated relA and spoT genes. The lacZ gene, another highly annotated gene (26% of the documents), that encodes the β-galactosidase enzyme responsible for the hydrolysis of β-galactosides into monosaccharides, contributed significantly (almost 50% of assignments) to the annotation of cellular functions implicated in the metabolism of carbon compounds (BC-1.1.1). However, in this particular case it should be acquainted that the occurrence of this gene in documents is frequently associated with molecular assays using lacZ as a reporter gene. Therefore, the relevance of this gene to the stringent response might be questionable.

The gene fis that encodes the Fis transcriptional dual regulator and the gene rpoB coding for the β subunit of the RNAP, contributed the most to the annotation of transcriptional related functions (BC-2.2.2). Similarly, genes like dksA that encodes the DksA protein, rplK that encodes the 50S ribosomal subunit L11, and rpsG and rpsL coding for the 30S ribosomal subunits S7 and S12, respectively, contributed the most to the annotation of translation related processes (BC-2.3.2). By looking into the frequencies, it was verified that there is a discrepancy of annotation between the genes contributing to enriched ontology terms and the corresponding gene products. Therefore, the use of the MultiFun ontology not only pointed out relevant gene function assignments, but also disclosed the participation of several gene products that, even being less reported in documents, were highlighted by functional association. Some examples are the 30S ribosomal subunit protein S12 and the 30S ribosomal subunit protein S7 encoded by rpsL and rpsG, respectively.

On the other hand, the analysis of GO biological process assignments (Table 7) highlighted metabolic and genetic information transfer processes as the most frequently assigned (i.e., over 50% of the documents have annotated concepts that were assigned to these ontology terms). Besides the general term "metabolic process" having the highest frequency (89% of the documents), two particular terms associated with metabolic processes: the "nucleobase, nucleoside and nucleotide interconversion process" (GO:0015949) and the "guanosine tetraphosphate metabolic process" (GO:0015969), had high frequencies (around 80% of the documents) as well. The gene product that contributed the most to the annotation of terms related with metabolic processes was the RelA enzyme, with over 80% of the assignments. Regarding ontology terms related with genetic information transfer, "transcription" (GO:0006350), "DNA-dependent transcription regulation" (GO:0006355) and "translation" (GO:0006412) were the most represented processes (56%, 52% and 40% of the documents, respectively). The RpoS or the alternative sigma factor σ38 that acts as the master regulator of the general stress response, the CRP transcriptional dual regulator, known to participate in the transcriptional regulation of genes involved in the degradation of non-glucose carbon sources and the Mfd protein, found to be responsible for ATP-dependent removal of stalled RNAPs from DNA, contributed similarly to the annotation of transcription and DNA-dependent transcription regulation processes, ranging between 10% and 20% of the assignments. Translation process assignments were derived from the RplK (or 50S ribosomal subunit protein L11) and the DksA proteins, with 28% of the assignments each, and the Elongation Factor Tu (EF-Tu), which mediates the entry of the aminoacyl tRNA into the ribosome, with 13% of the assignments.

We have paid particular attention to stress-specific ontology terms like the "response to stress" (GO: 0006950), the "response to starvation" (GO: 0042594), the "response to osmotic stress" (GO: 0006970) and the "response to DNA damage stimulus" (GO:0006974) that were assigned in almost 40% of the documents. The GO term "response to stress" was mostly assigned by the RecA regulatory protein, the RelB transcriptional repressor and the transcription antitermination protein NusA (frequencies of assignment of 20%, 16% and 10%, respectively). Regarding the GO term "response to starvation", SpoT enzyme detached from other contributing gene products (almost 70% of the assignments). The σ38 factor and the EF-Tu protein were the main contributors to the assignment of the GO term "response to osmotic stress" (59% and 34% of the assignments, respectively), while the assignment of "response to DNA damage stimulus" was mainly due to the annotation of proteins like Mfd, RecA and RecG (28%, 11% and 11% of the assignments, respectively). The process of restoring DNA after damage, associated with the GO term "DNA repair" (GO:0006281), was also assigned by the aforementioned annotated entities.

Since results evidenced considerable assignment of stress-related processes, it was considered interesting to explore in detail the functional annotations of gene products related to E. coli stress responses (Table 8). A decade-by-decade analysis was performed to evaluate the extent of documents that study entities associated with these functional annotations. As shown, the response to starvation (GO:0042594) was mostly evidenced in the last decade, being assigned in almost 70% of the documents of this decade. The response to DNA damage stimulus (GO:0006974) and osmotic stress (GO:0006970) were also considerably assigned in the last decade (50% of the documents). On the contrary, the defense response to bacterium (GO:0042742) was less assigned in the documents from the last two decades (less than 10% of the documents) and the stringent response (GO:0015968) was poorly assigned in the last decade, probably because GO only associates this biological process to the 50S ribosomal subunit protein L11, which only recently has been studied in the context of this stress.

Table 8.

Assignment of GO concepts related to stress responses.

| Frequency of Ontology Annotation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO Identifier | GO Concept | GO Description | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 |

| GO:0042594 | Response to starvation | A change in state or activity of a cell or an organism as a result of a starvation stimulus, deprivation of nourishment. | - | 15% | 28% | 68% |

| GO:0006974 | Response to DNA damage stimulus | A change in state or activity of a cell or an organism as a result of a stimulus indicating damage to its DNA. | 7% | 26% | 31% | 50% |

| GO:0006970 | Response to osmotic stress | A change in state or activity of a cell as a result of an increase or decrease in the concentration of solutes outside the cell. | 21% | 28% | 35% | 50% |

| GO:0006950 | Response to stress | A change in state or activity of a cell or an organism as a result of a disturbance in organismal or cellular homeostasis. | - | 31% | 46% | 46% |

| GO:0006979 | Response to oxidative stress | A change in state or activity of a cell or an organism as a result of oxidative stress. | - | 3% | 20% | 45% |

| GO:0009432 | SOS response | An error-prone process for repairing damaged microbial DNA. | - | 23% | 30% | 45% |

| GO:0046677 | Response to antibiotic | A change in state or activity of a cell or an organism as a result of an antibiotic stimulus. | - | 23% | 30% | 15% |

| GO:0042493 | Response to drug | A change in state or activity of a cell or an organism as a result of a drug stimulus. | - | 15% | 35% | 11% |

| GO:0009266 | Response to temperature stimulus | A change in state or activity of a cell or an organism as a result of a temperature stimulus. | - | - | 9% | 11% |

| GO:0042742 | Defense response to bacterium | Reactions triggered in response to the presence of a bacterium that act to protect the cell or organism. | 14% | 26% | 9% | 8% |

| GO:0015968 | Stringent response | A specific global change in the metabolism of a bacterial cell as a result of starvation. | - | 13% | 7% | 6% |

| GO:0009408 | Response to heat | A change in state or activity of a cell or an organism as a result of a heat stimulus. | - | 3% | 13% | 5% |

| GO:0009409 | Response to cold | A change in state or activity of a cell or an organism as a result of a cold stimulus. | - | - | - | 3% |

| GO:0009636 | Response to toxin | A change in state or activity of a cell or an organism as a result of a toxin stimulus. | - | - | - | 3% |

| GO:0009267 | Cellular response to starvation | A change in state or activity of a cell as a result of deprivation of nourishment. | - | - | - | 1% |

| GO:0046688 | Response to copper ion | A change in state or activity of a cell or an organism as a result of a copper ion stimulus. | - | - | - | 1% |

| GO:0009269 | Response to desiccation | A change in state or activity of a cell or an organism as a result of a desiccation stimulus. | - | - | 4% | - |

| GO:0031427 | Response to methotrexate | A change in state or activity of a cell or an organism as a result of a methotrexate stimulus. | - | - | 2% | - |

The frequency of annotation of stress response-related concepts was estimated for documents published in the four decades analysed (from 1970 to 2009).

Discussion

The aim of this work was to use literature mining to complement manual curation in the revision, systematisation and interpretation of current knowledge on the stringent response of E. coli. Literature mining was expected to help on the identification of important biological players and their molecular functions. The controlled vocabulary extracted from the EcoCyc repository (i.e. concepts that identify biological entities like genetic components, gene products and small molecules) and ontology terms from GO, MultiFun and PSI-MI ontologies were expected to support large-scale information processing and biological contextualisation.

The application of literature mining approaches has been tested in different biological fields [3,4,6,47-50], but it is known that the quality of the information extracted has to be ensured by manual curation. At present, manual curation can extract more detailed information from literature than it is possible by mining approaches, and more accurately define the participants and their roles. However, to achieve a broad coverage, both approaches can efficiently complement each other. As such, we propose a semi-automated approach to revise, systematise and interpret the current knowledge on the stringent response of E. coli, based on specific controlled vocabulary for the identification of biological entities involved in this process and complemented with manual curation. Results suggested that: (i) automatic literature retrieval is able to provide documents of interest whereas controlled vocabulary from publicly available databases can support the identification of relevant entities; (ii) ontology assignments enable entity contextualisation into cellular functions and biological processes, delivering a more comprehensive and biologically meaningful scenario; and (iii) statistical analysis identifies biological entities of interest and facilitates document indexing for additional manual curation. Ultimately, the literature mining approach presented clues on entities and associations of interest and suggested which documents in the corpus should be further inspected for details on given entities or processes.

The analysis performed to the final set of annotated concepts in the corpus, evidenced the (p)ppGpp nucleotides as some of the most annotated biological entities: the ppGpp nucleotide was annotated in 75% of the documents, and the broad term (p)ppGpp exhibited the highest average of annotations per document (Table 3). The extensive number of documents supporting these annotations evidenced that the role of (p)ppGpp nucleotides in the stringent response has been extensively studied. Corpus analysis disclosed that the relA gene product was also extensively studied. Indeed, over 70% of the documents addressed the activity of the relA gene and its product RelA. This enzyme was first associated to the synthesis of ppGpp in 1970 (PMID: 4315151) [51]. It is described that during amino acid deprivation the accumulation of this nucleotide increases above basal levels. Later, in 1980, the ppGpp level was found to be controlled by the SpoT enzyme via GTP hydrolysis activity (PMID: 6159345) [52]. However both the spoT gene and the SpoT enzyme have been annotated in only roughly 30% of the documents. In part, because RelA was the first enzyme discovered to be involved in the stringent response, but mostly because it is the first biological entity to respond to the amino acid starvation. Accordingly, "nucleobase, nucleoside and nucleotide interconversion" emerged as one of the most assigned ontology terms in the corpus, mainly due to the high frequency of assignment allocated to the RelA protein (80%). Transcriptional and translational processes were also highlighted by the analysis. The acknowledgment that (p)ppGpp nucleotides manipulate gene expression, so that gene products with important roles in the starvation survival are favoured at the expense of those required for growth and proliferation, has been widely reported (PMID:12123445; PMID:10809680) [12,53]. In vitro studies demonstrated that (p)ppGpp bind directly to the RNAP, affecting the transcription of many genes (PMID:4553835) [54]. Also, studies hypothesised that the configuration of the RNAP is altered, decreasing the affinity of the housekeeping sigma factor (i.e. σ70) to RNAP and thus, allowing other sigma factors to compete and influence promoter selectivity (PMID:12023304) [55]. As covered by the corpus analysis, besides RNAP (annotated in over 60% of the documents), four of the existing sigma factors in E. coli were also annotated: the σ38 that acts as the master regulator of the general stress response (annotated in 22% of the documents); the σ70 that is the primary sigma factor during exponential growth (annotated in 11% of the documents); the σ54 that controls the expression of nitrogen-related genes (annotated in 4% of the documents); and the σ32 that controls the heat shock response during log-phase growth (annotated in 3% of the documents). Although the regulation of transcription initiation is not yet fully understood, current knowledge suggests that these four sigma factors may interact with the RNAP during stringent control.

Regarding transcription-related ontology terms, the concepts that contributed the most to these assignments were: the β subunit of the RNAP (RpoB) to which (p)ppGpp nucleotides bind (PMID:9501189) [56]; the CRP transcriptional dual regulator that is activated in response to starvation conditions (PMID:10966109) [43]; the Fis transcriptional dual regulator, whose gene promoter is inhibited during the transcription initiation by the (p)ppGpp-bound RNAP (PMID:2209559; PMID:9973355) [33,34]; and the Mfd protein that releases the arrested RNAP-DNA complexes after (p)ppGpp nucleotides induce the transcription elongation pausing, protecting genome integrity during transient stress conditions (PMID:7968917) [57]. It is known that (p)ppGpp nucleotides not only modulate the RNAP activity, either by reducing the expression of genes like fis (which in turn modulates the expression of the crp gene) or increasing the expression of the σ38 gene, but also mediate the inhibition of the RNAP replication-elongation, which afterwards requires the Mfd protein to remove the stalled RNAPs (PMID:16039593; PMID:7968917) [57,58]. Although most studies have focused on the influence of the (p)ppGpp nucleotides on the mechanisms that regulate transcription initiation activities, their regulatory effects on the elongation of DNA transcription are also important. The combined control of the DNA transcription initiation and elongation are central to a prompter cellular response to nutritional starvation [11], which has been highlighted in the present study by the presence of associated concepts in the analysis.

Similarly, (p)ppGpp also influence certain translation-related processes. Studies showed that (p)ppGpp inhibits translation by repressing the expression of ribosomal proteins and also potentially inhibiting the activity of the particular proteins (PMID:7021151; PMID:11673421; PMID:6358217) [59-61]. Corpus analysis evidenced the annotation of ribosomal proteins, such as the 50S ribosomal subunit protein L11 and the 30S ribosomal subunit proteins S7 and S12, as well as the EF-Tu and the non-ribosomal DksA protein. The 50S ribosomal subunit protein L11 has been indirectly implicated in the feedback inhibition of (p)ppGpp, because ribosomes lacking this protein are unable to stimulate the synthesis of these nucleotides (PMID:11673421; PMID:17095013) [39,61]. The involvement of the DksA protein in translation processes was inferred through the inspection of functional assignments. As reported (PMID:16824105) [62], DksA regulates the posttranscriptional stability of σ38 factor, which increases dramatically when (p)ppGpp levels are high. Although these are the main (p)ppGpp interactions at the translational level, the impact of these nucleotides in the translation apparatus was further analysed based on the frequency of co-annotation of gene products with (p)ppGpp nucleotides that unveiled additional participants at this level. As a result, it was possible to perceive the relevance of specific translation GTPases known to be inhibited by (p)ppGpp nucleotides, namely: the Der protein that stabilises the 50S ribosomal subunit and the EF-G that facilitates the translocation of the ribosome along the mRNA molecules (PMID:8531889) [36].

Apart from identifying and contextualising numerous biological participants in the stringent response, the proposed analysis (in particular, the analysis of GO functional assignments) suggested that some of the biological entities involved in other stress responses may also participate in the stringent response. Responses to starvation, DNA damage and osmotic, oxidative and SOS stresses are some examples of stress responses that were also evidenced in the analysis of the corpus (over 30% of the documents). Yet, it was striking to notice that the stringent response concept was barely assigned, probably because few biological entities are currently associated with this GO term. In fact, the 50S ribosomal subunit protein L11 was the only entity in this corpus associated with that term. Nevertheless, several biological entities that interplay in different responses to stress were identified in the corpus, suggesting the overlap between stress responses. Although the relationship between these entities and the stringent response in this study is merely hypothetical, it was verified that their participation in the stringent response has been experimentally tested. For example: the link between the stringent response and the response to osmotic and oxidative stresses is likely to be via the involvement of the σ38 factor and the EF-Tu protein; the response to DNA damage stimulus was assigned to the RecA, RecG and Mfd proteins that were verified in literature to intervene in the early dissociation of the elongation complex stalled by ppGpp [58]; and finally, the RecA regulator and the UvrABC nucleotide excision repair complex have been implicated in the DNA repair process and SOS response [63].

With the extensive list of biological players retrieved from the corpus, it was possible to recognize and investigate most of the (p)ppGpp induced cellular processes. The major participants in the stringent response were highlighted by their frequency of annotation and their representativeness in the corpus. The (p)ppGpp nucleotides and the RelA and SpoT enzymes that control (p)ppGpp basal levels, along with the RNAP, were pointed as the most significant entities in the corpus. Nonetheless, corpus analysis also revealed the involvement of entities that have been disregarded or less reported in most recent revisions [9,11,17,24,25]. In most cases, this is due to the fact that the reviews are not focused on the detailed description of the molecular mechanisms involved in the stringent response. They reflect the current state of knowledge, including the different levels of cellular processes that are triggered during this stress response, but do not specify which biological entities are involved in these processes. However, researchers often need to compile this information, not only for experimental purposes, but also for computational modelling or to better understand the complexity of the response. Hence, in this study, the stringent response was associated with a large set of biological entities. We have validated the role of many of those entities by inspecting directly the literature used to build the corpus, therefore also validating the usefulness of the methodology developed. However, further validation would be necessary to have a broad description of the stringent response considering the large variety of biological entities directly or indirectly affected by the (p)ppGpp within specific metabolic, transcriptional and translational processes. The systematization of information on the stringent response of E. coli is therefore the greatest benefit from the methodology described in this work.

Besides collecting and organizing information into functional classes, we were able to analyse the advances accomplished in the investigation of the stringent response in E. coli. Comparing the annotations of biological concepts and concepts associated with experimental techniques (based on the PSI-MI ontology terms) we followed the evolution of knowledge being reported along four decades. Technological developments have promoted the discovery of many new entities and have clarified their roles in the stringent response. At the early stage of the study of the stringent response, some traditional experimental techniques were considered decisive in the identification of the main metabolic participants (see Figure 5 and Table 5), such as the (p)ppGpp nucleotides that have been investigated since the 70s. Yet, in the last decades, research efforts have been focused on the newest molecular biology techniques, namely high-throughput detection methods. In particular, techniques based on array technology have addressed the rapid screening of biological entities as well as molecular interactions (PMID: 18039766; PMID: 17233676) [64,65]. DNA microarrays have been used to inspect the genome-wide transcriptional profiles of E. coli (PMID: 18039766) [64]. This technology has also provided information on transcriptional regulation, determining negatively controlled promoters (typically involved in cell growth and DNA replication) and positively controlled promoters (the amino acid biosynthesis, the transcription factors, and/or alternative sigma factor genes). Although the reconstruction of the transcriptional regulatory structure of the stringent response is far from complete, these recent advances have brought a closer view of the pleiotropic nature of the response.

Finally, results showed that it is possible to scale-up conventional manual curation coping with the ever-increasing publication rate and, at the same time, provide automatic means of identifying and contextualising participants of interest. Beyond the accomplishments of the approach on this particular study, its extension to the analysis of other stress responses and/or organisms is fairly easy and interesting. However, although in the case of bacterial systems this might be simple, where naming conventions are straightforward and mostly followed by the community, in the case of other organisms, like Drosophila or plant systems, there will be more limitations. Adaptation to other scenarios implicates the compilation of sets of related documents and specialized controlled vocabularies that can be more elaborate and complex.

Methods

Semi-automatic information extraction approach

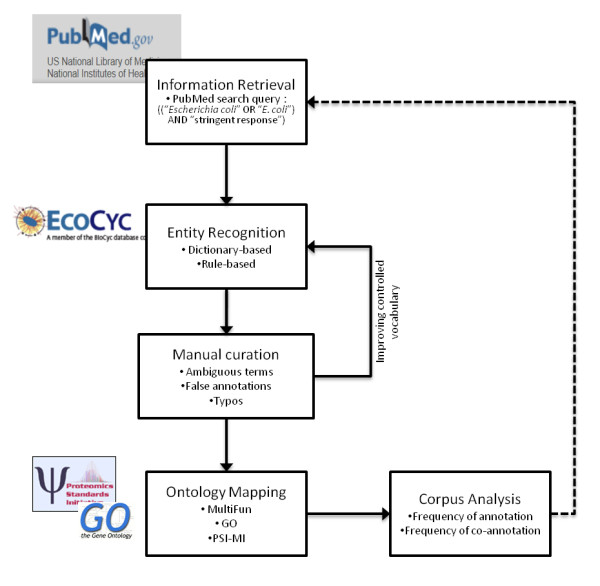

The semi-automatic information extraction approach designed to review existing literature on the stringent response of E. coli, integrated the following procedures: automatic document retrieval and entity recognition processes, manual curation and corpus analysis (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Semi-automatic information extraction approach. The first step encompasses the retrieval of relevant documents that are then processed to recognize biological concepts. In the following step, a manual curation procedure is undertaken to ensure the quality of the final corpus. Ontological terms are further mapped to enable functional enrichment analysis. The corpus analysis enables the identification of key players or significant information by an incremental curation that can further deliver information for retrieving new relevant documents.

The documents to be analysed were compiled through PubMed keyword-based searches in January 2010, using the terms ("Escherichia coli" OR "E. coli") and some variants of the term "stringent response" as reference. The process of document retrieval was limited to full-texts and it retrieved a total of 251 documents, from which only 193 full-text documents were used due to the availability of links to full text articles in PubMed and institutional journal subscriptions. The list of documents is provided in the Additional file 1.

The automatic identification of biological concepts in those documents was done in a subtask so-called entity recognition that seeks to locate and classify concepts in texts. These concepts correspond to names or textual descriptions that are listed in a structure called controlled vocabulary that was built using information from the EcoCyc database [28], a key resource for E. coli studies, and includes biological concepts used for the recognition of genetic components (genes, RNA and DNA molecules), gene products (i.e. proteins, including transcription factors and enzymes) and small molecules (or metabolites). Additionally, a hand-crafted dictionary supported the recognition of experimental techniques and their association to PSI-MI ontology terms. For each recognized concept in documents we have estimated the number of annotations, i.e. the number of times that that concept appears in the body texts (including all name variants associated with that biological concept).

@Note [66], a workbench for Biomedical Text Mining supported the entity recognition process. Its regular expression module enabled the identification of genes and proteins that adhere to standard gene and protein naming conventions for E. coli (e.g. three lower case letters followed by a fourth letter in upper case or a term consisting of four digits preceded by character 'b' are candidates for gene names) while the dictionary-based recognition module used the terminology extracted from EcoCyc and PSI-MI ontology.

The annotated corpus was stored into XML files for further analysis. The manual curation process consisted on reviewing concept annotations, i.e., the text markups (XML tags) for recognised entities, to ensure the corpus quality and consistency. Errors of the automated recognition process such as the annotation of false entities (e.g. the word 'cap', a name variant for the CRP transcriptional factor, was wrongly annotated or words like 'release' or 'crease' were annotated as enzymes based on common enzyme suffix 'ase'), homonyms (e.g. the same term 'elongation factor Tu' to designate two different polypeptides 'TufA' and 'TufB') and PDF-to-text format conversion typos (e.g. '4azaleucine' and '9galactosidase' were corrected to '4-azaleucine' and 'β-galactosidase', respectively) were manually curated.

Controlled vocabulary