Abstract

Most human seizures occur early in life, consistent with established excitability-promoting features of the developing brain. Surprisingly, the majority of developmental seizures are not spontaneous but are provoked by injurious or stressful stimuli. What mechanisms mediate ‘triggering’ of seizures and limit such reactive seizures to early postnatal life? Recent evidence implicates the excitatory neuropeptide, corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). Stress activates expression of the CRH gene in several limbic regions, and CRH-expressing neurons are strategically localized in the immature rat hippocampus, in which this neuropeptide increases the excitability of pyramidal cells in vitro. Indeed, in vivo, activation of CRH receptors – maximally expressed in hippocampus and amygdala during the developmental period which is characterized by peak susceptibility to ‘provoked’ convulsions – induces severe, age-dependent seizures. Thus, converging data indicate that activation of expression of CRH constitutes an important mechanism for generating developmentally regulated, triggered seizures, with considerable clinical relevance.

The majority of seizures occurring in the developing human are not spontaneous, that is, they are not related to inherent abnormalities in the balance of neuronal excitation and inhibition1. Rather, most seizures during infancy and childhood are provoked or triggered by alterations in the normal milieu of excitable neurons2. Thus, rapid triggering by fever, hypoxia or trauma provokes the majority of seizures in the infant and young child. These seizures – a manifestation of rapid and transient enhancement of neuronal excitability in response to adverse and potentially injurious agents – demonstrate an exquisite age specificity (Table 1): febrile seizures are exclusive to infancy and early childhood1,2, immediate traumatic seizures (as opposed to posttraumatic epilepsy) are far more common in the young human compared with the adult, and anoxia-related seizures occur primarily in the full-term neonate5,7. Other seizures that are not genetic in origin, such as infantile spasms, which have been linked to a large number of injuries of the CNS and stressors that include infections and malformations, are highly age specific and primarily restricted to the first year of life6.

TABLE 1.

Provoked seizures occurring predominantly or exclusively during development

| Seizure type | Trigger | Age specificity (human) | Predominant/exclusive | References for animal model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Febrile | Fever | Infants and young children | Exclusive | Baram et al.3 Holtzman et al.4 |

| Hypoxic | Decreased brain oxygenation | Neonates | Predominant | Jensen et al.5 |

| Infantile spasms | Multiple (‘stressors?’) | Infants | Exclusive | None, reviewed by Baram6 |

In the present review, we focus on novel and evolving concepts regarding potential mechanisms for the rapid transduction of stressful alterations of neuronal milieu into enhanced excitability and resulting seizures. We discuss the cascade of molecular events triggered by ‘stress’, with an emphasis on the excitatory neuropeptide, corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). Established and novel in vivo and in vitro evidence for the role of CRH in enhancing excitation in key limbic circuits, particularly in the tri-synaptic hippocampal pathway, are discussed. Finally, we describe recent data regarding the receptors that mediate CRH-induced excitation, and provide the probable mechanisms underlying the remarkable age specificity of the proconvulsant effects of this neuropeptide. We conclude that CRH is a likely candidate for modulating excitability in response to triggers such as fever, hypoxia or trauma, which result directly in developmentally regulated, clinically important seizures.

The dilemma: the immature brain is more excitable – but spontaneous seizures, in the absence of prior injury, are uncommon

It is generally considered that the immature brain is more excitable than the adult brain (see Ref. 8 for a recent review). This concept is supported in the human by the much greater incidence of seizures in the infant and young child, as compared with the adult1,2,9. Enhanced excitability and a higher sensitivity to proconvulsant agents have also been demonstrated in immature experimental animals, including rats, cats and monkeys10,11. Several characteristics of developing neuronal circuitry might account for this enhanced excitability8,12. For example, GABA, the principal inhibitory neurotransmitter in the mature CNS, has depolarizing, and thus excitatory, properties during the first postnatal week in the rat12,13. In addition, excitatory amino acid receptors are both more abundant in the immature brain14 and possess a subunit makeup that promotes neuronal depolarization15. These factors are thought to contribute to an altered excitation–inhibition balance during development8. At the circuit level, increased neuronal excitability is evident, leading, for example, to the robust long-term potentiation observed during the second postnatal week (‘infancy’ in the rat) in both hippocampal and cortical synapses16,17. In addition, the number of cortical and hippocampal excitatory synapses is highest during this period and decreases after the third post-natal week18. All of these factors favor enhanced excitation and a propensity to generation and propagation of seizures8.

Although possessing enhanced intrinsic excitability and sensitivity to proconvulsant agents, the immature brain is primarily engaged in normal neuronal functions. Indeed, the vast majority of immature humans and rodents do not generate spontaneous seizures (although experimental or other developmental injury can lead to reactive epilepsy at this age). Surprisingly, even genetically determined spontaneous seizures (genetic epilepsies) typically begin later than the ‘excitable’ developmental period19,20. During the neonatal and infancy periods in the human, seizures are most commonly ‘triggered’, that is, they are induced by acute and adverse alterations of the ‘normal’ neuronal milieu21. Thus, stressful circumstances, such as trauma, anoxia, fever or hypoglycemia, lead rapidly (within minutes) to enhanced excitability and seizures. Animal models of febrile convulsions3 and anoxic seizures5 document the restricted period of susceptibility to these seizures in the rat, which is confined to the second postnatal week3,22,23.

In summary, the immature brain is prone to seizures8, yet generation of seizures is selective: spontaneous intrinsic and genetic seizures are relatively uncommon, while rapidly triggered seizures can be provoked by diverse stressful signals.

Stressful signals activate the excitatory neuropeptide CRH

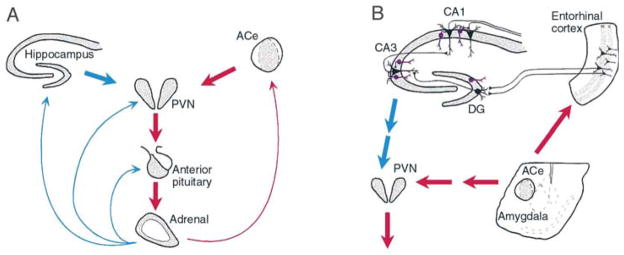

Candidate mechanisms for the rapid stress-induced excitation of limbic neurons emerge from analyses of the molecular events induced by stress (Fig. 1). It has been well established that the CNS responds to stressful circumstances by rapid hormonal, autonomic and behavioral alterations, designed to enable survival in potentially adverse situations and restore a steady state24,25. The major mediator of the hormonal and behavioral responses to stress is the neuropeptide CRH (Refs 26,27). Within seconds of exposure to stress, CRH, located in peptidergic neurons in the paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus (PVN), is secreted from nerve terminals to influence rapid hormonal secretion from corticotrophs in the anterior pituitary28,29 (Fig. 1A). In addition, stress upregulates transcription of the CRH gene in the PVN within seconds30,31 (Fig. 2), leading to increased steady-state expression of CRH-encoding mRNA (Refs 29,32).

Fig. 1. The neuroendocrine (A) and limbic (B) interactive, stress-activated corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) loops.

(A) Stress-conveying signals rapidly activate immediate–early genes in CRH-expressing neurons of the central nucleus of the amygdala (ACe). Rapid CRH release in the ACe is associated with CRH-expression in hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and secretion of CRH into the hypothalamo–pituitary portal system, inducing ACTH and glucocorticoid secretion from the pituitary and adrenal, respectively. Glucocorticoids exert a negative feedback on the PVN (directly and via the hippocampus), yet activate expression of the CRH gene in the amygdala, potentially promoting further CRH release in this region. (B) CRH-expressing GABAergic interneurons (purple cells) in the principal cell layers of the hippocampal CA1, CA3 and the dentate gyrus (DG) are positioned to control excitability of the pyramidal and granule cells, respectively. These neurons might be influenced by stress-evoked release of CRH from the ACe, via connections in the entorhinal cortex. For both panels, red and blue arrows denote established or putative potentiating and inhibitory actions, respectively. Arrows do not imply monosynaptic connections.

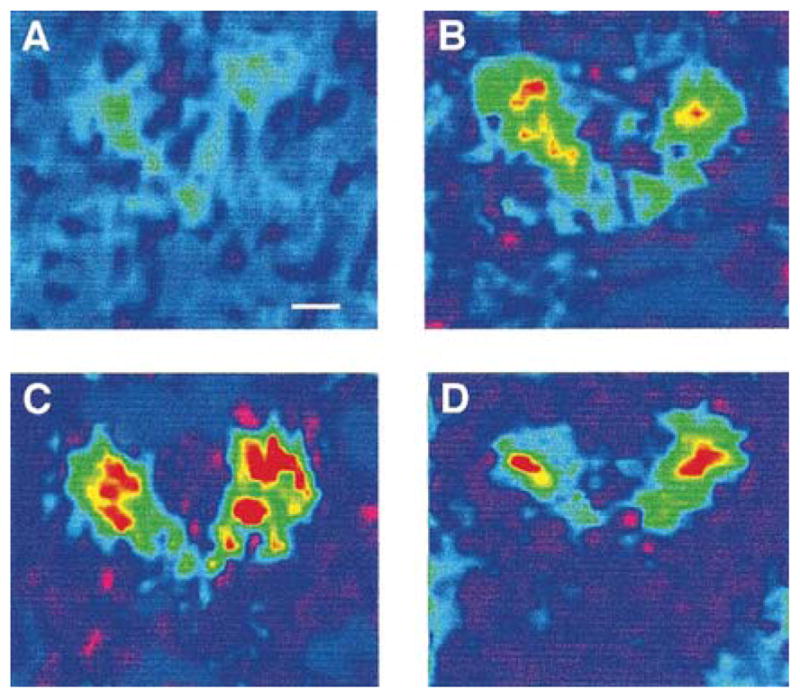

Fig. 2. Rapid activation of expression of the corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) gene by stress in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus.

Coronal brain sections were subjected to in situ hybridization using an intronic probe recognizing only heteronuclear RNA (hnRNA, unedited) encoding CRH. (A) Sections derived from stress-free 9-day old pups, sacrificed within 20 s of disturbance, show little CRH hnRNA-specific signal. (B) CRH expression is evident, by 2 min from the onset of stress, and (C) peaks by 15 min. CRH hnRNA levels decline by 30 min from the onset of stress (D), while total CRH-specific mRNA is increased for at least 4 h after stress29. Scale bar in (A), 300 μm.

It has increasingly been recognized, however, that the actions of CRH as a neuromodulator of stress are not confined to the neuroendocrine, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal system (Fig. 1). Behavioral studies have demonstrated activation and arousal induced by this peptide in a number of species27,33. These CRH-induced behaviors are indistinguishable from behaviors observed under stressful circumstances34. Furthermore, administration of CRH-receptor antagonists can abolish typical stress-induced behaviors35,36. Interestingly, this blocking effect is demonstrable when the antagonists are injected into the amygdala, suggesting that the site of stress-induced CRH-receptor activation lies at least partially within this limbic region37 (Fig. 1B).

Studies of the distribution of CRH in the adult and developing CNS have demonstrated the presence of significant populations of CRH-expressing neurons in discrete limbic regions38,39. In particular, a large cluster of CRH-expressing neurons is located in the central nucleus of the amygdala38,39. These cells are rapidly activated by stress to express immediate–early genes40 and CRH-encoding mRNA (Refs 41,42). Stress-induced release of CRH from these amygdala neurons is evident from microdialysis data and from local infusion of competitive CRH-receptor antagonists37,43. CRH interacts with specific postsynaptic G-protein-coupled receptors44–46 to alter intracellular cAMP levels.

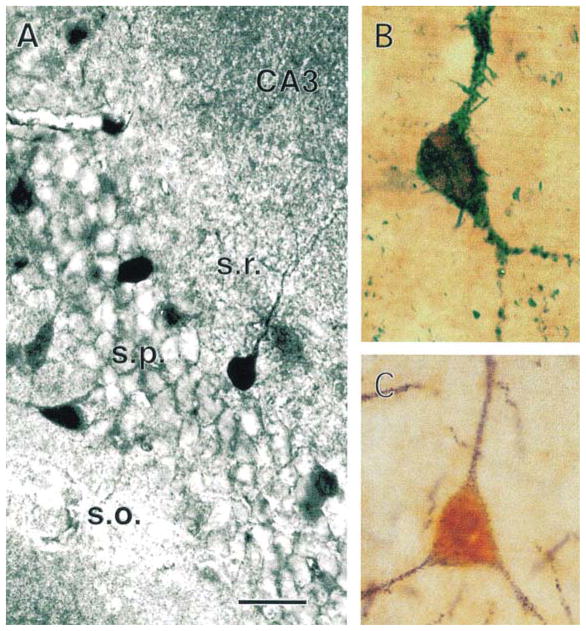

Scattered CRH-immunoreactive neurons have also been localized to the hippocampal formation of the adult rat38,47,48. Interestingly, recent detailed double-labeling and ultrastructural studies in the hippocampal formation of the immature (10–13-day old), unstressed rat have demonstrated a robust population of CRH-expressing GABAergic interneurons49. Specifically, numerous, large CRH-immunoreactive neurons are found in CA3 strata pyramidale and oriens, and fewer in the corresponding layers of CA1 and in stratum lacunosum-moleculare of Ammon’s horn. In the dentate gyrus, CRH-immunoreactive cell bodies are confined to the granule cell layer and hilus. Ultrastructurally, CRH-expressing neurons have aspiny dendrites and their axon terminals form axosomatic and axodendritic symmetric synapses with pyramidal and granule cells. Other CRH-immunoreactive terminals were found to synapse on axon initial segments of principal neurons. The vast majority of CRH-expressing neurons are co-immunolabeled for the GABA-synthesizing enzyme isoforms GAD-65 and GAD-67 and most also contain parvalbumin, but none were labeled for calbindin (Fig. 3). These findings establish the presence of a significant, heterogeneous population of hippocampal CRH-immunoreactive GABAergic interneurons. Furthermore, a subpopulation of neurons that express both CRH and parvalbumin, located within and adjacent to the principal cell layers, consists of basket and chandelier cells. Thus, axon terminals of these CRH-expressing interneurons are strategically positioned to influence the excitability of the principal hippocampal neurons via release of both CRH and GABA (Ref. 49).

Fig. 3. Distribution and characterization of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH)-expressing neurons in the hippocampus.

(A) Immunolabeled CRH-expressing neurons within and adjacent to the pyramidal (s.p.) layer of CA3. (B) A double-labeled neuron, expressing both CRH (brown) and an isoform of glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD-65), the GABA-synthesizing enzyme (blue–green). (C) An interneuron reacting with antibodies to both CRH (orange) and parvalbumin (plum red). Scale bar, 50 μm in (A), 15 μm in (B) and 20 μm in (C). Abbreviations: s.o., stratum oriens; s.r., stratum radiatum. Modified, with permission, from Yan et al.49

In summary, the neuropeptide CRH functions within the hypothalamus to regulate rapid hormonal responses to stress. However, the precise and selective distribution of CRH neurons within the amygdala and hippocampus allows rapid release of this peptide to affect the excitability of principal neurons and neuronal circuits within these key limbic regions.

What are the neurophysiological effects of CRH?

The actions of CRH on neurons have been investigated both in vivo and in vitro, in neuronal populations as diverse as the locus coeruleus and cerebellum. For the purposes of this review, we focus on limbic neurons and discuss in vivo and in vitro studies in the mature and the developing rat.

In the adult rat in vivo, Ehlers et al. described long-latency (h) seizures induced by CRH, with onset in the amygdala50, whereas Marrosu et al. recorded epileptiform discharges in the hippocampus after administration of CRH (Ref. 51). The long latency and behavioral characteristics of CRH-provoked seizures in adult rats suggested that CRH might lower the seizure threshold or act otherwise as a ‘kindling stimulus’ for the development of limbic seizures52,53. Weiss et al. demonstrated that preadministration of CRH significantly accelerated the development of stage 3 kindled seizures in mature male rats53. The duration of after-discharge throughout the kindling process was significantly longer in the CRH-pretreated animals. The data were interpreted to suggest a role for endogenous CRH in limbic excitability and a mechanistic interaction with the kindling process.

In the neonatal and infant rat (first and second postnatal weeks, respectively), administration of CRH into the cerebral ventricles leads to seizures within minutes54,55. The seizures, best characterized on postnatal days 10–13, resemble other limbic seizures behaviorally56,57. Using multiple bipolar depth electrodes, the earliest recorded epileptiform discharges produced by CRH are detected in the amygdala55 and propagate to the hippocampus58. Both the electrophysiological and the behavioral seizures provoked by CRH in the developing rat persist for several hours59,60, and require doses (7.5 × 10−12 mol) that are 200 times smaller than those required for generation of seizures in adults. Significantly, these doses of CRH, by themselves, do not elevate the concentration of plasma corticosterone54, excluding the possibility that glucocorticoids are involved in the initiation of CRH-produced seizures. This is particularly important in view of the established effects of corticosterone, acting via glucocorticoid-receptor activation, on Ca2+ currents in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons61. However, CRH-induced and other seizures constitute a stressful event, leading to marked elevations of plasma corticosterone54, so that a later potentiation of hippocampal-neuron excitability by glucocorticoids cannot be excluded. In addition, in vivo studies in the immature rat indicate that, unlike in the adult, activation or blocking of CRH receptors does not alter any measure of the acquisition or maintenance of kindling62,63.

CRH promotes excitability in hippocampal circuitry

Clearer insight into the effects of CRH on neuronal excitability has emerged from in vitro studies. Intracellular electrophysiological recordings from hippocampal CA1 and CA3 pyramidal neurons of adult rat revealed that CRH increased the firing of CA1 pyramidal neurons in response to excitatory input, and reduced afterhyperpolarization following an action-potential train elicited by depolarizing current64. Similar findings were obtained in the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala65.

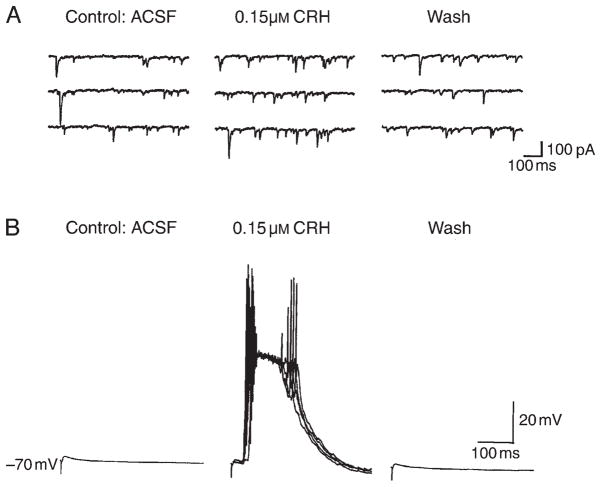

In the immature rat (10–13 days old), field recordings demonstrated increased amplitudes of population spikes elicited in CA1 after administration of CRH (Refs 66,67). These changes were reversed with peptide wash-out and were prevented by preapplication of a CRH-receptor blocker. Because of the high expression of CRH receptors in the CA3 pyramidal cell layer68, whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed on hippocampal CA3 neurons. These studies (confirming the findings of Aldenhoff et al.64 in the adult) demonstrated that CRH increased significantly the number of spikes elicited by depolarizing current pulses. Thus, these findings indicate that, in the presence of a strong depolarizing influence and action potential firing in the network, CRH can enhance excitability by increasing the number of output action potentials of a given cell. CRH increased the frequency of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) by an average of 252% (Fig. 4A), but did not alter the amplitude or kinetic properties of miniature EPSCs, indicating a lack of a direct postsynaptic effect of the peptide on AMPA-type glutamate receptors. Similarly, CRH did not alter the amplitude of the pharmacologically isolated, evoked monosynaptic glutamatergic currents. However, when the mossy fiber-evoked responses were recorded from CA3 pyramidal cells in current-clamp mode in the presence of bicuculline (Fig. 4B), CRH caused the appearance of large bursts of action potentials at variable latency. The bursts of action potentials appeared to be elicited by longer latency and most likely polysynaptic EPSPs, in agreement with the observation that CRH increases the firing of pyramidal cells elicited by a given excitatory input67.

Fig. 4. Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) enhances excitability of hippocampal pyramidal neurons.

(A) Reversible increase in the frequency of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents with application of CRH (middle panel). Whole-cell recording of a CA3 pyramidal neuron was performed in voltage-clamp mode (−60 mV). (B) Large, synchronized, variable-latency discharges of CA3 neurons in current-clamp mode (in the presence of bicuculline) are elicited by stimulation of mossy fibers in the presence of CRH. These action-potential discharges are longer-latency, probably polysynaptic, excitatory postsynaptic potentials, and are fully reversed when CRH is removed. Abbreviation: ACSF, artificial cerebrospinal fluid. Modified, with permission, from Hollrigel et al.67

Taken together, these data suggest that a given excitatory stimulus in the network can be amplified by CRH, causing hyperexcitability, while in the absence of any other depolarizing input, CRH does not lead to epileptiform neuronal activity (and seizures). However, the peptide markedly enhances excitatory input (or spontaneous discharges) of CA3 pyramidal neurons, with a robust increase in the numbers of spikes, consistent with hyperexcitability. It should be noted, however, that the postsynaptic effects of synthetic CRH applied in the hippocampal slice preparation might not fully represent the activation of CRH-expressing interneurons. The latter is expected to generate the release of both endogenous CRH and GABA, leading to a potentially different net influence on principal hippocampal cells. Indeed, the neuroanatomical data showing CRH-immunoreactive interneurons synapsing on the somata and axon initial segments of principal hippocampal neurons, combined with the electrophysiological data discussed above, provide compelling evidence for the ability of CRH to create an excitable state in the immature hippocampal circuit.

Support for the ability of CRH to enhance the excitability of the immature CNS in vivo is provided by the finding that repeated infusions of CRH leads to a striking augmentation of the convulsant potency of subsequently administered kainic acid69. A threshold kainic acid dose, which resulted only in short bouts of automatisms in control rats, produced status epilepticus in rats pretreated with CRH four times over two days. Other investigators have shown that repeated amygdaloid seizures result in prolonged upregulation of expression of the CRH gene in GABAergic interneurons in the dentate gyrus70. Thus, CRH-mediated neuro-transmission might promote excitability and lead to limbic seizures, which, in turn, increase the level of CRH at critical hippocampal synapses, further enhancing excitability in a positive-feedback manner.

In conclusion, converging in vitro and in vivo data indicate that CRH might induce a neuronal excitable state. In the presence of CRH-receptor activation, mild glutamatergic input is amplified to result in epileptic discharges and, potentially, in seizures. It has been established that CRH is secreted rapidly after stress in the hypothalamus and the amygdala, and ongoing studies are focused on determining the effect of specific stressors on release of CRH from hippocampal terminals. Thus, currently available data support a scenario in which select stressful circumstances lead to rapid release of CRH, which transforms normal glutamatergic excitatory input to amygdala and hippocampal neurons into epileptic output.

What are the postsynaptic mechanisms mediating CRH-induced excitability? Why are the peptide’s effects most prominent in the developing brain?

Specific G-protein-coupled receptors for CRH have been mapped to the adult46,71 and immature rat limbic system68,72. Of the two characterized members of the CRH-receptor family – CRF1 and CRF2 – selective non-peptide antagonists indicate that CRF1 activation is required for the excitatory effects of the neuropeptide60. Both binding studies and receptor type-specific in situ hybridization have shown that CRF1-receptor levels peak in the hippocampus and the amygdala during development (postnatal days 6 and 9, respectively), at 400–600% of adult levels68,73. The increased abundance of CRH receptors might partially explain the potent proconvulsant effects of this peptide during the first weeks of life. Rapid Ca2+ influx after application of CRH has been demonstrated in a variety of cell types, including astrocytes, corticotrophs and neurons74–76. Administration of CRH has been shown to injure immature hippocampal CA3 and amygdala neurons77,78. In addition, recent evidence points to a role for endogenous CRH in hippocampal neuronal death after glutamate-receptor activation, ischemia or status epilepticus in the adult79–81, perhaps contributing to the induction of pro-epileptic changes in neuronal excitability82. Taken together, these data indicate that under circumstances leading to enhanced availability of CRH at abundant CRF1-receptor sites in the immature hippocampus, the neuropeptide not only enhances excitation but potentiates excitotoxicity in selected limbic circuits.

Conclusions: the significance of CRH to developmental seizures in the human

The present review has focused on the potential role of CRH, a stress neurohormone, as the key neuromodulator of triggered excitability in the developing brain. Many features of the immature brain promote excitability, but the relative paucity of spontaneous seizures suggests that a balance of excitation and inhibition exists during this period under steady-state conditions. Perturbation of this balance by select injurious or stressful signals might lead to seizures, via enhanced secretion of CRH, which acts on specific receptors in the hippocampus and amygdala to promote excitability. CRH receptors in these regions are maximally expressed during the time of peak CRH-induced excitability and of propensity to triggered seizures, suggesting that regulation of expression of CRH receptors might play a key role in modulating the ability of extrinsic signals to provoke limbic seizures. In human infants, certain age-specific seizures respond to ACTH, a downregulator of CRH synthesis83,84, and CRH-receptor antagonists increase seizure threshold in an animal model of febrile seizures, the most common age-specific seizures of the developing human85,86. These data further support the notion that selective blockers of CRH-receptor activation might be useful anticonvulsants for age-specific, provoked seizures in the developing human.

Acknowledgments

The constructive critiques of Drs I. Soltesz, C.M. Gall, C.E. Ribak and S. Shinnar, and the help of G. Hollrigel and X-X. Yan are appreciated. The authors’ work summarized in this review was supported by NIH grants NS28912, NS35439 and HD34975.

Selected references

- 1.Berg AT, Shinnar S. J Child Neurol. 1994;9 (Suppl 2):S19–S26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berg AT, et al. Epilepsia. 1995;36:334–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb01006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baram TZ, Gerth A, Schultz L. Dev Brain Res. 1997;246:134–143. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(96)00190-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holtzman D, Obana K, Olson J. Science. 1981;213:1034–1036. doi: 10.1126/science.7268407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen FE, et al. Ann Neurol. 1991;29:629–637. doi: 10.1002/ana.410290610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baram TZ. Ann Neurol. 1993;33:231–236. doi: 10.1002/ana.410330302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Volpe JJ, editor. Neurology of the Newborn. Saunders; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holmes GL. Epilepsia. 1997;38:12–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb01074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hauser WA. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1995;6:419–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Purpura DP, Prelevic S, Santini M. Exp Neurol. 1968;22:408–422. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(68)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kubova H, Moshe SL. J Child Neurol. 1994;9 (Suppl 1):S3–S11. doi: 10.1177/0883073894009001031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ben Ari Y, et al. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:523–529. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ben-Ari Y, et al. J Physiol. 1989;416:303–325. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnston MV. Epilepsia. 1996;37 (Suppl 1):S2–S9. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb06018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monyer H, Seeburg PH, Wisden W. Neuron. 1991;6:799–810. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90176-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDonald JW, Johnston MV. Brain Res Rev. 1990;15:41–70. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(90)90011-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crair MC, Malenka RC. Nature. 1995;375:325–328. doi: 10.1038/375325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swann JW, et al. Epilepsy Res (Suppl) 1992;9:115–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Metrakos K, Metrakos JD. In: Genetics of Epilepsy. Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW, editors. North Holland Publishing; 1974. pp. 429–439. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noebels JL. Neuron. 1996;16:241–244. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Traub RD, Miles R. Neural Networks of the Hippocampus. Cambridge University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hjeresen DL, Diaz J. Dev Psychobiol. 1988;21:261–275. doi: 10.1002/dev.420210307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jensen FE, et al. Epilepsia. 1992;33:971–980. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1992.tb01746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sapolsky R. Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers. W.H. Freeman; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herman JP, Cullinan WE. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:78–84. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vale W, et al. Science. 1981;213:1394–1397. doi: 10.1126/science.6267699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heinrichs SC, et al. Ann New York Acad Sci. 1995;771:92–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb44673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rivier J, Spiess J, Vale W. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:4851–4855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.15.4851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yi SJ, Baram TZ. Endocrinology. 1994;135:2364–2368. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.6.7988418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kovacs KJ, Sawchenko PE. J Mol Neurosci. 1996;7:125–133. doi: 10.1007/BF02736792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kovacs KJ, Sawchenko PE. J Neurosci. 1996;16:262–273. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-01-00262.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lightman SL, Young WS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:4306–4310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.11.4306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winslow JT, Newman JD, Insel TR. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1989;32:919–926. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koob GF, et al. Ciba Found Symp. 1993;172:277–295. doi: 10.1002/9780470514368.ch14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cole BJ, et al. Brain Res. 1990;512:343–346. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90646-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tazi A, et al. Regul Pept. 1987;18:37–42. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(87)90048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swiergiel AH, Takahashi LK, Kalin NH. Brain Res. 1993;623:229–234. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91432-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swanson LW, et al. Neuroendocrinology. 1983;36:165–186. doi: 10.1159/000123454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gray TS, Bingaman EW. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1996;10:155–168. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v10.i2.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Honkaniemi J, et al. J Neuroendocrinol. 1992;4:547–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1992.tb00203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kalin NH, Takahashi LK, Chen FL. Brain Res. 1994;656:182–186. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91382-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hatalski CG, Guirguis C, Baram TZ. J Neuroendocrinol. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1998.00246.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Merlo Pich E, et al. J Neurosci. 1995;15:5439–5447. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-08-05439.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Souza EB, et al. J Neurosci. 1985;5:3189–3203. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-12-03189.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lovenberg TW, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:836–840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Potter E, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:8777–8781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Merchenthaler I. Peptides. 1984;5:53–69. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(84)90265-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sakanaka M, Shibasaki T, Lederis K. J Comp Neurol. 1987;260:256–298. doi: 10.1002/cne.902600209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan XX, et al. Hippocampus. 1998;8:231–243. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1998)8:3<231::AID-HIPO6>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ehlers CL, et al. Brain Res. 1983;278:332–336. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90266-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marrosu F, et al. Epilepsia. 1988;29:369–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1988.tb03733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weiss GK, Castillo N, Fernandez M. Neurosci Lett. 1993;157:91–94. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90650-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weiss SR, et al. Brain Res. 1986;372:345–351. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91142-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baram TZ, Schultz L. Dev Brain Res. 1991;61:97–101. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(91)90118-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baram TZ, et al. Ann Neurol. 1992;31:488–494. doi: 10.1002/ana.410310505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haas KZ, Sperber EF, Moshe SL. Dev Brain Res. 1990;56:275–280. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(90)90093-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ben-Ari Y. Neuroscience. 1985;14:375–403. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baram TZ, Hatalski CG. In: Developmental Epilepsies. Moshe SL, Wasterlain C, Nehlig A, editors. John Libbey; in press. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baram TZ, et al. Mol Psychiatry. 1996;1:223–226. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baram TZ, et al. Brain Res. 1997;770:89–95. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00759-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Karst H, Wadman WJ, Joels M. Brain Res. 1994;649:234–242. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Baram TZ, Hirsch E, Schultz L. Dev Brain Res. 1993;73:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(93)90048-f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baram TZ, Hirsch E, Schultz L. In: Kindling. 5. Corcoran M, Moshe SL, editors. Plenum Press; 1998. pp. 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aldenhoff JB, et al. Science. 1983;221:875–877. doi: 10.1126/science.6603658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rainnie DG, Fernhout BJ, Shinnick-Gallagher P. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;263:846–858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smith BN, Dudek FE. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:2328–2333. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.5.2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hollrigel GS, et al. Neuroscience. 1998;84:71–79. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00499-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Avishai-Eliner S, Yi SJ, Baram TZ. Dev Brain Res. 1996;91:159–163. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(95)00158-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brunson KL, Schultz L, Baram TZ. Dev Brain Res. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00130-8. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Smith MA, et al. Brain Res. 1997;745:248–256. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01157-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chalmers DT, Lovenberg TW, De Souza EB. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6340–6350. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06340.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Insel TR, et al. J Neurosci. 1988;8:4151–4158. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-11-04151.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pihoker C, Cain ST, Nemeroff CB. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1992;16:581–586. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(92)90063-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Takuma K, et al. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;199:1103–1107. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kuryshev YA, Childs GV, Ritchie AK. Endocrinology. 1996;137:2269–2277. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.6.8641175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Weiss JH, Yin HZ, Baram TZ. Epilepsia. 1996;37 (Suppl 5):27. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ribak CE, Baram TZ. Dev Brain Res. 1996;91:245–251. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(95)00183-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Baram TZ, Ribak CE. NeuroReport. 1995;6:277–280. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199501000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lyons MK, Anderson RE, Meyer FB. Brain Res. 1991;545:339–342. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91310-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Maecker H, et al. Brain Res. 1997;744:166–170. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01207-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Strijbos PJ, Relton JK, Rothwell NJ. Brain Res. 1994;656:405–408. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91485-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wheal HV, et al. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:135–175. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01182-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Snead OC, et al. Neurology. 1989;39:1027–1031. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.8.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Baram TZ, et al. Pediatrics. 1996;97:375–379. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Baram TZ, Schultz L. Ann Neurol. 1994;36:487. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Toth Z, et al. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4285–4294. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-11-04285.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]