Abstract

Developing organisms require nutrients to support cell division vital for growth and development. An adaptation to stress, used by many organisms, is to reversibly enter an arrested state by reducing energy-requiring processes, such as development and cell division. This “wait it out” approach to survive stress until the environment is conductive for growth and development is used by many metazoans. Much is known about the molecular regulation of cell division, metazoan development and responses to environmental stress. However, how these biological processes intersect is less understood. Here, we review studies conducted in Caenorhabditis elegans that investigate how stresses such as oxygen deprivation (hypoxia and anoxia), exogenous chemicals or starvation affect cellular processes in the embryo, larvae or adult germline. Using C. elegans to identify how stress signals biological arrest can help in our understanding of evolutionary pressures as well as human health-related issues.

Keywords: anoxia, C. elegans, cell cycle arrest, hypometabolism, L1 diapause, quiescent oocytes, stress, suspended animation

Hypometabolism and Arrest

Eukaryotic organisms inhabit and survive environmentally severe ecosystems, such as icy glaciers, high mountaintops and deep caves.1-5 Indeed, organisms have adapted to and perhaps even thrive in these environments, which are perceived as extreme from a human perspective; an adaptive mechanism organisms use to survive a stressful or changing environment is to reversibly enter into a hypometabolic state.6 In a hypometabolic state, key biological processes such as development, cell division, metabolism and gene expression are either slowed or arrested. Given the unique environments organisms have adapted to and that metazoan development is typically linked to a rapid cell division of blastomeres, one must wonder how cellular processes are arrested in organisms exposed to extreme environments. In this review, we first discuss aspects of hypometabolism, as well as how the use of the model system Caenorhabditis elegans has been used to study, at the cellular and genetic level, environmentally induced arrest of cell division.

Examples of hypometabolic states include diapause, dormancy, quiescence, cryptobiosis, suspended animation and hibernation. The environmental cues that initiate hypometabolic states include nutrient deprivation, desiccation, reduced temperatures, day light cycles and oxygen deprivation. Central to the ability for an organism to survive a stressful environment is the capacity to reduce energy-consuming processes and reallocate energy to processes that help maintain and exit from a hypometabolic state. Metazoans that enter into a hypometabolic state due to environmental stress include, but are not limited to, turtles, frogs, insects, killifish, nematodes and tardigrades.4,7-9 In some cases, the environment to which the organism has adapted is quite extreme. For example, the Antarctic nematode Plectus murrayi has the remarkable capacity to survive desiccation and low temperatures.10 Interestingly, the first metazoans, of the phyla Loricifera, which live permanently in an anoxic environment (sediments in the L’Atalante basin), have recently been identified.11 How cellular processes, such as cell division, occur in such a habitat is not understood.

A comprehensive understanding of the effect the environment has on cell division is of interest to human health-related issues and to identifying how environment has shaped evolutionarily conserved processes fundamental to metazoan life. Because of the central importance cell division has in human-related diseases, much effort and resources are put into determining the regulatory mechanisms governing cell division in yeast, mammalian cell culture, adult somatic cells and blastomeres of developing embryos. The majority of these experiments are done within laboratory conditions that support cell division; much less is understood about the adaptive mechanisms and evolutionary pressures that shaped cell division in organisms that inhabit extreme environments. Questions to ponder include how cellular processes central to cell division, such as microtubule polymerization, chromosome condensation and segregation as well as nuclear envelope formation and breakdown, occur in the organisms that survive extreme environments, or if these processes merely arrest until the environment is more conducive for cell division.

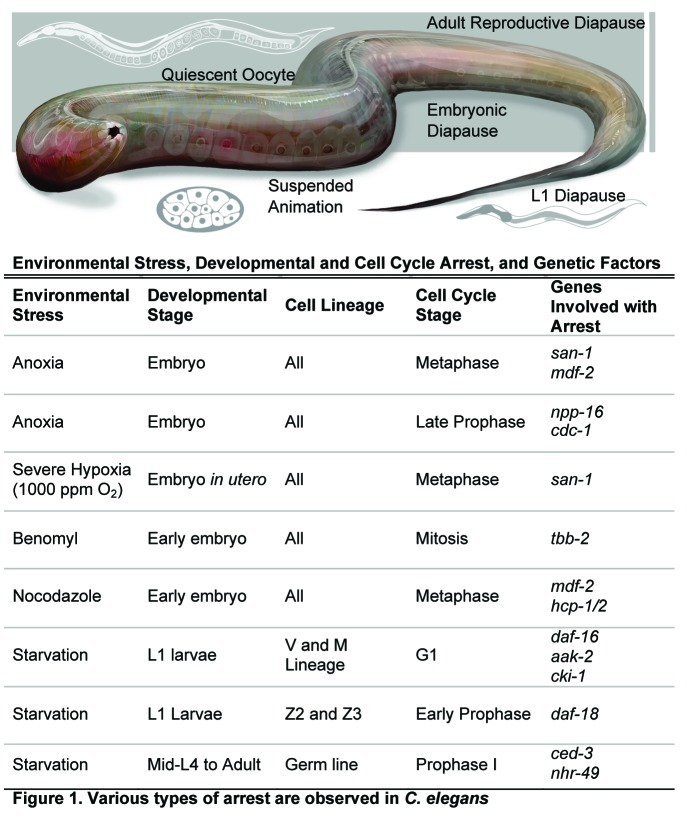

The soil nematode Caenorhabditis elegans has the capacity to survive some extreme environments and is a powerful developmental and genetic model system in which mechanistic details important for stress responses and hypometabolism can be uncovered. For example, decades of work led to an understanding of the environmentally induced dauer larvae state.12,13 The signaling pathways (insulin/IGF-1 and TGFβ) known to regulate dauer formation are also involved with other biological processes, including lifespan, development and other stress responses; many reviews have been written on this topic, and it is therefore not a focus of this review. What is less understood, and the topic of this review, is what physiological or environmental conditions modify the cell cycle machinery and induce a reversible arrest in C. elegans (Fig. 1). Environmentally induced arrest includes L1 diapause, anoxia-induced suspended animation, adult reproductive diapause, embryonic diapause and chemically induced arrest. Physiologically induced arrest can occur as a normal process during development and aging. For example, quiescent oocytes, due to a depletion of sperm, are observed in the aging adult hermaphrodite. Further investigation of these events will elucidate how cell cycle progression is regulated by metabolic states within metazoans.

Figure 1. Various types of arrest are observed in C. elegans.

Anoxia-induced Cell Cycle Arrest

C. elegans is able to survive severe oxygen deprivation (anoxia; <0.001 kPa O2) by entering into a state of reversible suspended animation. Suspended animation is a hypometabolic state in which observable processes, such as development, cell division, motility, feeding and egg laying, are arrested. Although all life cycle stages arrest when exposed to anoxia, here we will focus on anoxia-induced cell cycle arrest observed in the embryo. Embryos in a state of suspended animation have a marked reduction in the ATP-to-ADP ratio, indicative of a hypometabolic state. There is also a decrease in the detection of phosphorylated cell cycle-regulated proteins recognized by mAb MPM-2, suggesting that post-translational modifications could have a role in the regulation of reversible cell cycle arrest.14

Blastomeres of embryos exposed to anoxia arrest in three stages of the cell cycle: interphase, prophase and metaphase, with each stage bearing unique hallmarks of arrest. Suspended blastomeres arrest cell cycle progression and microscopically visible movement of the chromosomes comes to a halt.14-17 In interphase cells, the chromatin appears more condensed and localizes to the inner nuclear periphery.16 Anoxia does not appear to induce a specific stage of interphase arrest, since a consistent localization of centrosomes has not been observed. However, other interphase markers need to be implemented into experiments to further characterize anoxia-induced interphase arrest. In anoxia-arrested prophase blastomeres, the chromosomes are highly condensed and associate near the inner nuclear periphery. Using a GFP-tagged histone strain and time-lapse microscopy to track chromosomes, it was shown that prophase chromosomes move in a dynamic fashion within the nucleus as they condense. However, the chromosomes of prophase blastomeres exposed to anoxia move to the inner nuclear periphery and remain in this state until air is added back to the environment.17 Furthermore, the centrosomes are duplicated and on polar opposite sides of the nucleus, indicating that anoxia arrest occurs in late prophase. It is likely that nuclear envelope breakdown is prevented, stopping the blastomere short of a commitment to enter mitosis.17 In the anoxia-arrested metaphase blastomere, microtubules are depolymerized further, thus hindering the ability of the cell cycle to progress normally and potentially contributing to the induction of arrest.16 These cell biological analyses suggest that the embryos sense and respond to the change in oxygen tension, arrest energy expending processes and enter into a truly hypometabolic state. Upon re-exposure to normoxia, the embryos recover ATP stores and exit the suspended animation state.14 It is remarkable that this arrest can be maintained for several days in the embryo, a state of suspended animation in which blastomeres are arrested at interphase, late prophase and metaphase, and upon re-oxygenation, cell cycle progression continues, and development proceeds normally. This suggests that there is a “cellular signature” that is maintained in the arrested embryo, so that cell division, development and differentiation is re-initiated and coordinated post anoxia-induced arrest.

A genetic approach to identify genes involved with anoxia-induced cell cycle arrest has elucidated how low levels of oxygen regulate cell division (Fig. 1). It is known that a deletion in the gene encoding the well-studied transcription factor hypoxia-induced factor (HIF-1) does not lead to a decrease in viability in the embryo exposed to anoxia. HIF-1 is essential for embryos exposed to hypoxia, thus the mechanisms to adjust to hypoxia or arrest in response to anoxia are not overlapping.14,18,19 Genes involved in regulating anoxia-induced arrest have been identified for blastomeres arrested in metaphase and prophase. Proper arrest of blastomeres in metaphase requires the function of the spindle checkpoint genes san-1 and mdf-2.15,20 A reduction of the spindle checkpoint function via RNA interference or genetic mutations results in a decrease in embryo viability while exposed to anoxia and abnormal nuclei with an anaphase bridge phenotype.15 Prophase arrest requires the function of the nucleoporin NPP-16/NUP50 and likely involves the function of the cyclin-dependent kinase CDK-1.17 Embryos with reduced npp-16 function (either by mutation or by RNAi) have blastomeres that do not properly arrest at prophase when exposed to anoxia. Instead, nuclear envelope breakdown proceeds, and the cell commits to continue through mitosis despite lacking polymerized microtubules. Condensed chromosomes form a disorganized type of metaphase plate and arrest, but the cell is not able to recover when re-exposed to normoxia. Additionally, immunostaining indicates that CDK-1 is misregulated in NPP-16-deficient embryos exposed to anoxia. When activated by phosphorylation, CDK-1 translocates to the nucleus and promotes entry into mitosis. In wild-type embryos exposed to normoxia, activated CDK-1 is found in prophase blastomeres; but in embryos exposed to anoxia, activated CDK-1 is not found in arrested prophase nuclei. NPP-16-deficient embryos have a wild-type CDK-1 localization pattern in normoxia, but when exposed to anoxia, activated CDK-1 is found within prophase nuclei. This pattern indicates that CDK-1 is improperly regulated in NPP-16-deficient embryos only when exposed to anoxia, suggesting that NPP-16 interacts with CDK-1 to promote anoxia-induced prophase arrest. Additionally, NPP-16 function is related specifically to prophase arrest, as metaphase and interphase arrest are unaffected by npp-16 loss of function. Additional work is needed to elucidate the mechanism by which NPP-16 contributes to the promotion of anoxia-induced prophase arrest.

Embryos exposed to anoxia or hypoxia have the ability to survive by entering into a state of suspended animation or initiating HIF-1 signaling response, respectively.14,19,21 However, embryos exposed to severe hypoxia (0.25–1 kPa O2) do not survive.22 Embryos exposed to this severe hypoxia display an abnormal morphology and either terminally arrest as dead embryos or as abnormal larvae that do not survive. If the embryos are exposed to carbon monoxide, the hypoxia death phenotype is suppressed by inducing suspended animation.22 Within a gravid adult exposed to severe hypoxia (1,000 ppm O2), the embryos will arrest. The adult exposed to this severe hypoxia continues to be motile and is thus not in a state of suspended animation; however, reproductive features do arrest. The embryonic arrest in utero is referred to as embryonic diapause. The spindle checkpoint gene san-1 is required for these embryos to maintain viability, but hif-1 is not required for viability when the animal is exposed to this severe hypoxia.23 However, unlike wild-type animals, the hif-1 or aak-2 (codes for α-subunit of AMPK) mutants, when exposed to 5,000 ppm O2, suspended reproductive activities, and the embryos in utero arrest.23 These results further underscore the idea that the genetic pathways that initiate an environmentally induced arrest vary and are dependent on the type of stress. That is, anoxia, severe hypoxia or moderate hypoxia trigger different, but perhaps overlapping, molecular responses within the cell. The signal of severe hypoxia (1,000 ppm O2) to the cell cycle machinery to arrest cell division is not understood.

Chemical Arrest

It is of interest to induce arrest in C. elegans with chemicals or drugs both to facilitate study and imaging, but also as a means to better understand embryonic and larval development. Chemically induced developmental arrest has been described in the embryo, larval and adult stages of C. elegans. However, there are few chemicals that have been shown to effectively and reversibly arrest the cell cycle in the embryo. This is likely due to the presence of the eggshell, which is largely impermeable, preventing uptake of many of the available drugs and chemicals. The embryo’s eggshell can be permeablized by using a slight pressure, laser puncturing or by RNAi of the gene perm-1; these methods are useful for assessment of early embryonic development.24 However, the caveat is that each of these methods results in some level of embryonic lethality, making studies past early embryogenesis difficult.

Inhibition or downregulation of mitochondrial respiration reduces metabolic levels, and because cell cycle progression is an energy requiring process, mitochondria are good targets for small-molecule or chemical inhibitors to induce an arrested state. Electron transport chain inhibition by sodium azide (inhibitor of complex IV) has been shown to arrest the cell cycle in the embryo, with embryos displaying a phenotype very similar to that of anoxia-induced arrest. However, recovery is only possible if the embryo is exposed to sodium azide for no more than 30 min; after this time, survivorship rapidly decreases.17 Why direct inhibition of the electron transport chain for brief periods (<1 h) leads to a decrease in viability yet long exposures to anoxia (>3 d) is not understood. Similar to the embryo exposed to anoxia, the embryo exposed to sodium azide contains prophase blastomeres, with chromosomes associated with the inner nuclear periphery. This indicates that the electron transport chain has an effect on the signal to relocate the chromosomes to the inner nuclear periphery. It remains to be determined if this is a direct signal due to a reduction in ATP, or if other signals are involved with the arrest. Chemical inhibition of the other mitochondrial complexes has not been demonstrated to induce cell cycle arrest in the embryo.

Alternatively, arrest can be induced not by reducing the energy available for the cell cycle, but by interrupting processes required for cell cycle progression. Chemical microtubule inhibitors have been shown to have variable effects on embryonic development. In wild-type embryos, the drug benomyl does cause an arrest; this arrest is dependent on the function of the β-tubulin gene tbb-2. Additionally, nocodazole-mediated depolymerization of microtubules was shown to slow mitosis and to activate the spindle checkpoint.25 In contrast, colchicine and vinblastine do not arrest mitotic divisions in the embryo but do seem to reduce the number of divisions compared with controls.26 It is not known if recovery is possible after exposure to these drugs, nor is it understood why some of the inhibitors have a significant affect while others do not.

Arrest of larvae and adults has been more widely analyzed due in part to the many anesthetics that are utilized for live animal imaging. Sodium azide also causes paralysis in larvae and in the adult, but recovery is possible for a longer period of time.27 The combination of tricaine and tetramisole is also widely used as an anesthetic for live imaging, resulting in larval and adult body wall muscle paralysis, but allows embryonic cell divisions to continue.28 The mitochondrial inhibitors antimycin A and siccanin have both been shown to arrest larval development but not embryonic development.29 Additionally, brief exposure to hydrogen sulfide causes a state of suspended animation in adult C. elegans that is reversible up to a threshold, but it has not been reported whether there is any effect on embryonic development.30,31 The mechanisms by which many of these chemicals induce cell cycle arrest are not understood, although there have been studies investigating other aspects, such as the mechanism of survival.27

Starvation-induced L1 Diapause

One of the major reasons why C. elegans has contributed to our understanding of development is that it has an invariant lineage: each pattern of cell division during development is precise between animals and can be genetically dissected.32,33 In general C. elegans blastomeres progress through a rapid cell division within the first half of embryogenesis. Some of these blastomeres during later stages of embryogenesis become quiescent and arrest at the G2 phase of the cell cycle. Cell cycle arrest is maintained until signals are established in the cell to promote cell cycle progression during this later stage of development.34,35 An additional example of cellular arrest includes the blastomeres that develop and differentiate into the germ cells that then arrest in early prophase, as noted by condensed chromosomes and duplicated centrosomes which are not on opposite sides of the nucleus.36,37 At any given time during embryogenesis, the blastomeres can be under different cell cycle control, because they progress through the cell cycle at different rates or reversibly arrest at specific times in development.

The coupling of cell cycle machinery to developmental regulators in itself is complex, and adding the extra layer of environmental stress to the analysis contributes to the difficulty of these studies. How environmental stress influences cell cycle progression during development is being addressed in C. elegans. The response C. elegans has to nutrient starvation is dependent on the stage of development and at the cellular level depends on cell type. How starvation arrests cell cycle progression can be studied in the L1 larvae. Embryos that are hatched in the absence of food resulted in arrest of L1 larvae, referred to as L1 diapause.38 L1 diapause can be maintained for several days, yet extended periods of starvation lead to a decrease in viability; after 28 d of starvation, approximately 35% of the L1 larvae remain alive. This indicates that the arrested L1 larva has a means to survive extreme starvation, and this environmental stress will suppress growth, development and cell cycle progression. During L1 diapause, there is a reduction in global gene expression; however, various metabolic genes are differentially regulated. Interestingly, it was determined that RNA Pol II is poised at the promoter of genes involved with growth and development, indicating that transcriptional regulation is likely an important aspect of maintenance and exit from L1 diapause. Data indicates that L1-arrested animals have a global overall reduced level of gene expression, however, some genes are actively transcribed.39

Although many cells have completed cell division upon hatching, there are cells that continue to divide during larval development. These cell divisions are arrested in L1 diapause animals. Mutations in the insulin-like signaling pathway are known to affect the phenotype of L1, diapaused animals. First, it has been shown that mutations in the daf-2 gene, which codes for the insulin-like receptor, leads to a low penetrant phenotype of larval arrest even in the presence of food. The daf-2(e1370) and daf-2(e979) mutants have approximately 10% and 70% larvae arrest, respectively, when grown at 25.5°C in the presence of food.38 If the animals are shifted down to 15°C, then the arrest is reversed. Further, the L1 arrest of daf-2 mutants is suppressed by mutations in the gene daf-16, which codes for the FOXO transcription factor. These initial findings led to investigation as to whether there was a link between the insulin-like signaling pathway and cell cycle arrest. Further studies found that a mutation in the daf-2 gene resulted in an increased survival rate when starved, whereas a mutation in daf-16 leads to a decrease in survival in starved L1 larvae. Furthermore, this same study found that mutations in genes that code for heat shock factor (hsf-1) or AMPK α subunit (aak-2) led to L1 sensitivity to starvation. The inability of daf-16 and aak-2 mutants to survive L1 starvation coincides with their reduced ability to arrest development. The cells that divide post-embryonically in the V and M lineage are arrested in starved wild-type L1 larvae, but this cell cycle arrest was not observed in the starved L1 larvae containing mutations in daf-16 or aak-2 mutants, indicating that these gene products have a role in cell cycle arrest for these cell lineages. The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, CKI-1 (p27Kip1 homolog) is present in the V lineage seam cells of starved animals but is absent or diminished in the starved daf-16 mutant. CKIs function to block cell division by inhibiting cyclin-dependent kinases necessary for cell cycle progression.40 It is thought that DAF-16 regulates the expression of cki-1, which can then suppress cell division in response to stress. This provides a link between a well-known pathway involved with environmental sensing and a regulator of cell division. There are mutations in genes that lead to defects in L1 diapause, such as tbc-2 or miR-71, that do not result in abnormal cki-1 expression, indicating that the arrest of cell cycle progression in the starved L1 larvae is regulated by a subset of genes, and not all defects in L1 diapause are due to abnormal cell cycle arrest.41

The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor CKI-1 is essential for regulation of cell cycle arrest in many cells in C. elegans. Embryonic cells lacking cki-1 will continue to progress through cell division, whereas ectopic expression of CKI-1 will induce a premature arrest at G1.34,42 However, the germline precursor Z2 and Z3 cells deviate from this pattern in that they are quiescent in animals lacking cki-1 and cki-2, indicating that cell division in the germ cells and somatic cells are likely differentially regulated.36 Furthermore, in both the embryo and the starved L1 larvae, the Z2 and Z3 cells contain chromatin that is condensed, appear to have a 4N DNA content and contain two centrosomes that have yet to migrate, thus indicating that these cells arrest after S phase at the G2 phase of the cell cycle.37 Mutations in daf-18, the PTEN homolog, result in a failure of the Z2 and Z3 cells to arrest in the starved L1 larvae. Interestingly, daf-18(nr2037) animals that are starved contain Z2 and Z3 cells that continue to divide even when starved for three days, supporting the idea that daf-18 blocks mitotic progression in germ cells in L1 diapause animals. The abnormal germ line proliferation phenotype, observed in daf-18 mutants starved as L1 larvae, is suppressed by mutations in age-1 and akt-1, indicating that DAF-18 acts to regulate the cell proliferative activity of AGE-1 and AKT-1. However, mutations in daf-16 did not suppress the abnormal proliferative activity in the daf-18 mutant, indicating that mitotic arrest of the germ cells in starved L1 larvae is not identical to the genes that regulate dauer formation. Together, these data show that components of the insulin/IGF-1 like pathway regulate arrest of the germ cells in starved L1 larvae.

Quiescent Oocytes

An essential process for eukaryotic cells is the specialized cell division of primordial germ cells to produce haploid gametes. Conserved meiotic processes include pairing of homologous chromosomes, synapsis between them, crossover events and accurate chromosome segregation. In mammals, the process of meiosis occurs over a prolonged period of time; oogonia enter meiosis but arrest at prophase I at the diplotene stage. The arrest of a mammalian oocyte is regulated by hormones and maturation-promoting factors, including cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK1).43 The conserved mechanisms regulating metazoan meiotic arrest is not completely understood. It is known that prolonged arrest affects the viability of the oocyte, resulting in a decreased ability to produce offspring. In both C. elegans and humans, oocytes will degrade functionally with age. The affect that stress-induced arrest has on oocyte viability in young or old organisms has not been fully examined.

Early in the development of the C. elegans hermaphrodite, the germ cells are phenotypically distinct from the somatic cells. The P2 cell in the four-cell embryo contains germ line-specific molecules such as P-granules and will divide to ultimately produce the primordial germs cells Z2 and Z3.44-46 At embryo hatching, the Z2 and Z3 germ cells are flanked by the somatic gonad precursors Z1 and Z4. These four cells are quiescent until mid-L1 larvae stage. By the L2 larval stage, the Z1 and Z4 proliferate to 12 cells, including two distal tip cells that are critical for germ line proliferation. Robust germ line proliferation occurs during larvae development and ultimately produces many meiotic cells organized within the adult gonad. The first germ cells produced are sperm, and subsequent meiosis results in the development of oocytes. Thus, a young adult contains approximately 300 mature sperm within the spermatheca, and the remaining assembly of meiotic cells differentiates into oocytes that eventually pass through the spermatheca to get fertilized. There is a coupling of oocyte maturation, ovulation and fertilization, where oocyte maturation is under the control of major sperm protein. Known environmental or physiological changes that arrest fertilization result in quiescent oocytes. Here, we highlight aspects of oocyte arrest in C. elegans for aged animals as well as animals exposed to stresses.

An aged hermaphrodite becomes depleted of sperm and fertilization will cease unless mated with a male, indicating that in post-sperm depleted animals, the oocytes remain viable.47,48 The oocyte is influenced by maternal age, in that the quality of the oocyte does decline with an increase in the age of the hermaphrodite; the oocyte quality does not seem to be related to the absolute number of eggs produced during the adult lifespan.49 Studies suggest that an extended arrest of germ cells is detrimental to oocyte quality. Furthermore, apoptosis of some of the germ cells is needed to maintain oocyte quality. It is thought that germ cell death is needed to allocate resources in the germline and thus increase oocyte quality.49 Aging animals appear to have difficulty providing sufficient resources for mature oocytes.

Animal oocyte viability decreases with age as assayed by morphological and viability issues of the embryo. Chromosomal abnormalities, such as aneuploidy and nondisjunction, are major causes of mammalian embryo defects. In C. elegans, nondisjunction events appear to increase in oocytes from aged animals, and there is a significant increase in the number of abnormal oocytes in older animals.50 In fact, by day 8 of adulthood, the oocytes in wild-type hermaphrodites are visibly degraded, smaller, fuse into a large cluster and become packed in the uterus. Mutations in genes from the insulin-like signaling pathway or TGFβ pathway (daf-2 and sma-2, respectively) produce a significantly higher number of viable offspring, and there is a reduction of nondisjunction events or abnormal oocyte phenotypes as the animal ages, indicating that these two pathways are involved with oocyte maintenance. The daf-2 and sma-2 mutants had a significantly higher level of apoptosis; this may contribute to the capacity to maintain oocyte viability as the animal ages.50

Young adult wild-type animals grown in normal laboratory conditions will produce embryos over the first four to five days of adulthood, with the majority of embryos laid during day one and two of adulthood. The oocyte maturation rate is fairly rapid and consistent in these young adults. However, the young adult exposed to anoxia will arrest many processes, including ovulation, fertilization and egg laying.51 Oocytes in the adult hermaphrodite are in diakinesis of prophase I and contain observable bivalent chromosomes. The anoxia-induced arrested oocytes contain bivalent chromosomes that associate with the inner nuclear membrane. This is referred to as “chromosome docking”, because live cell imaging showed that upon exposure to anoxia, the chromosomes closely associate with the inner nuclear membrane and no longer move within the nucleoplasm. These oocytes can maintain an arrest for at least one day, are viable upon re-oxygenation and have the capacity to be fertilized and produce offspring.17 Starved adult hermaphrodites do not have oocytes with docked bivalent chromosomes, whereas animals exposed to the electron transport inhibitor sodium azide do have oocytes in which some of the bivalent chromosomes are associated with the inner nuclear membrane. Perhaps the relevance to chromosome docking is a means to maintain the chromosomes while the cell is in an arrested state.

In regards to the stress of starvation, it is likely that the means of starvation and time of development of the starvation may influence the effect it has on the germline. It is known that starvation initiates programs leading to hypometabolic states, including diapause and quiescence. In C. elegans, it has been reported that starvation will induce a reproductive diapause in the adult hermaphrodite.52 In this report it, was observed that when mid-L4 larvae stage wild-type hermaphrodites were removed from a food source, the animals reached adulthood but had halted reproductive activities (termed adult reproductive diapause); these starved animals were observed to remain viable for up to 30 d. The authors indicated that the adult reproductive diapause phenotype may be dependent on a high-population density, suggesting that perhaps a molecule may be produced by the animals to influence this germ line plasticity, perhaps analogous in concept to dauermone. A characteristic of adult reproductive diapause was inhibition of embryo development; one or two embryos were retained in the uterus and observed to be viable for at least the first five days of starvation. Plasticity of the germ line was observed in these starved animals, in that the germ line had a decreased number of germ cells per gonad arm. Reintroduction to food led to recovery, suggesting that the germ line stem cells were maintained during this stress. Experiments with ced-3 mutants (caspase required for apoptosis) showed that programmed cell death is an important factor for extending the reproductive potential of starved worms. Furthermore, mutations in nhr-49 led to a decrease in adult reproductive diapause. NHR-49 is homologous to HNF-4a protein that mediates induction of fatty acid oxidation and gluconeogenesis in response to food deprivation.52 At this time, it is not clear what signals from starvation lead to arrest of cell division in meiotic and mitotic cells. A perceived challenge with these experiments is that the environmental stress must be tightly controlled to observe the phenotype.

The age-induced or sperm-depleted quiescent oocyte has several characteristic features that deviate from oocytes in young hermaphrodites. Large ribonuclear proteins (RNP) form in quiescent oocytes; P-granule associated proteins (PGL-1, GLH-1,2), RNA binding proteins (MEX-1, MEX-3) and specific maternal mRNAs are associated with the large RNP foci observed in quiescent oocytes.53,54 Furthermore, the large RNP foci that are observed in quiescent oocytes also share characteristics with stress granules, in that known stress granule markers co-localize. Stresses such as heat shock, osmotic stress and anoxia also induced the formation of RNP foci in oocytes. Thus, it appears that the formation of RNP foci occurs in stressed or arrested oocytes.53 It is possible that the formation of such RNP in quiescent or stressed oocytes is linked with maintenance of vital macromolecules important for translation or maintenance of mRNAs. In many metazoans, oocytes are arrested for many years prior to fertilization, and an extended arrest that is accompanied by aging affects the viability of the oocyte. Thus, a greater understanding of the cellular characteristics of quiescent oocytes will lead to a greater understanding of how meiotic cells maintain an arrest and how aging influences such arrest.

Conclusion

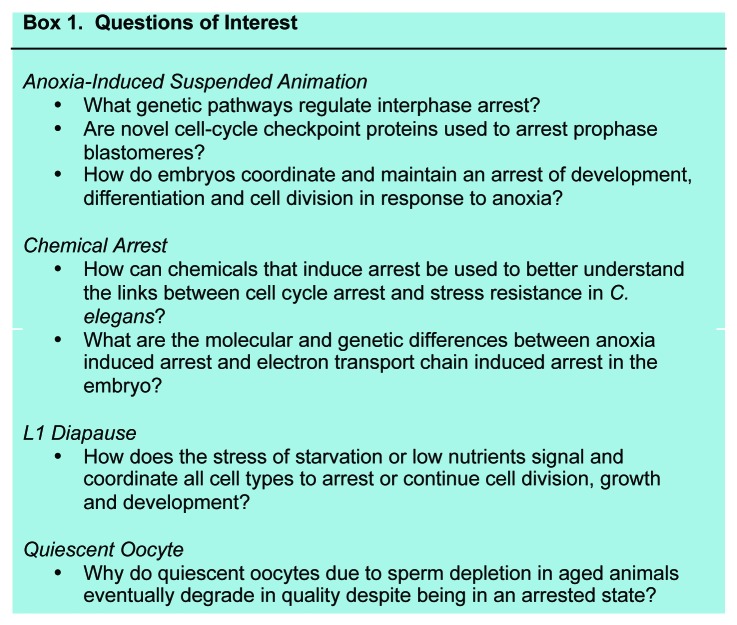

There is no doubt that understanding the molecular mechanisms that regulate fundamental processes such as cell division and cell cycle progression is of great interest. In the course of evolution, fluctuating nutrients such as reduced oxygen and food sources most certainly influenced the signaling pathways regulating cell division during the course of development. Genetic and cellular analysis using C. elegans has significantly increased our understanding of development. However, with the exception of dauer development, much less is understood at the molecular level about how environmental stress regulates developmental trajectories. Furthermore, how these environmental stress or states of quiescence are regulating or interacting with the cell cycle machinery is far from being understood. There are many questions that remain unanswered (Fig. 2). It is not known if the well-worked out cell cycle processes (for example the spindle checkpoint) contribute to arrest or slowing of cell cycle progression for all or just some stresses. It is not understood what the links are between metabolic state of the organism and regulation of the cell cycle machinery. It is unlikely that all of these mechanisms work similarly in all cell types at all stages of development and differentiation in animals exposed to various stresses. It is clear that many unanswered questions exist, yet further analysis in laboratory model organisms such as C. elegans will help our understanding of how stressful environments shaped fundamental biological processes and the evolution of living systems (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Questions of interest.

Acknowledgments

Work has been supported by a National Science Foundation CAREER grant to P.A.P. We gratefully thank Lacy Finn for graphic art assistance shown in Figure 1. Finally, we thank and appreciate input and comments from members of the Padilla Lab and the Developmental Integrative Biology Group at UNT.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/19444

References

- 1.Borgonie G, García-Moyano A, Litthauer D, Bert W, Bester A, van Heerden E, et al. Nematoda from the terrestrial deep subsurface of South Africa. Nature. 2011;474:79–82. doi: 10.1038/nature09974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Danovaro R, Company JB, Corinaldesi C, D’Onghia G, Galil B, Gambi C, et al. Deep-sea biodiversity in the Mediterranean Sea: the known, the unknown, and the unknowable. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11832. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Møbjerg N, Halberg KA, Jørgensen A, Persson D, Bjørn M, Ramløv H, et al. Survival in extreme environments - on the current knowledge of adaptations in tardigrades. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2011;202:409–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2011.02252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson DC, Ultsch GR. Physiology of hibernation under the ice by turtles and frogs. J Exp Zool A Ecol Genet Physiol. 2010;313:311–27. doi: 10.1002/jez.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tartaglia LJ, Shain DH. Cold-adapted tubulins in the glacier ice worm, Mesenchytraeus solifugus. Gene. 2008;423:135–41. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hochachka PW, Somero GN. Biochemical Adaptations Oxford University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guidetti R, Altiero T, Rebecchi L. On dormancy strategies in tardigrades. J Insect Physiol. 2011;57:567–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark MS, Worland MR. How insects survive the cold: molecular mechanisms-a review. J Comp Physiol B. 2008;178:917–33. doi: 10.1007/s00360-008-0286-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Podrabsky JE, Garrett ID, Kohl ZF. Alternative developmental pathways associated with diapause regulated by temperature and maternal influences in embryos of the annual killifish Austrofundulus limnaeus. J Exp Biol. 2010;213:3280–8. doi: 10.1242/jeb.045906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adhikari BN, Wall DH, Adams BJ. Effect of slow desiccation and freezing on gene transcription and stress survival of an Antarctic nematode. J Exp Biol. 2010;213:1803–12. doi: 10.1242/jeb.032268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danovaro R, Dell’Anno A, Pusceddu A, Gambi C, Heiner I, Kristensen RM. The first metazoa living in permanently anoxic conditions. BMC Biol. 2010;8:30. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riddle DL, Albert PS. Genetic and Environmental Regulation of Dauer Larva Development. 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fielenbach N, Antebi AC. C. elegans dauer formation and the molecular basis of plasticity. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2149–65. doi: 10.1101/gad.1701508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Padilla PA, Nystul TG, Zager RA, Johnson AC, Roth MB. Dephosphorylation of cell cycle-regulated proteins correlates with anoxia-induced suspended animation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:1473–83. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-12-0594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nystul TG, Goldmark JP, Padilla PA, Roth MB. Suspended animation in C. elegans requires the spindle checkpoint. Science. 2003;302:1038–41. doi: 10.1126/science.1089705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hajeri VA, Trejo J, Padilla PA. Characterization of sub-nuclear changes in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos exposed to brief, intermediate and long-term anoxia to analyze anoxia-induced cell cycle arrest. BMC Cell Biol. 2005;6:47. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-6-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hajeri VA, Little BA, Ladage ML, Padilla PA. NPP-16/Nup50 function and CDK-1 inactivation are associated with anoxia-induced prophase arrest in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:712–24. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-09-0787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Powell-Coffman JA. Hypoxia signaling and resistance in C. elegans. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21:435–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang H, Guo R, Powell-Coffman JA. The Caenorhabditis elegans hif-1 gene encodes a bHLH-PAS protein that is required for adaptation to hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7916–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141234698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hajeri VA, Stewart AM, Moore LL, Padilla PA. Genetic analysis of the spindle checkpoint genes san-1, mdf-2, bub-3 and the CENP-F homologues hcp-1 and hcp-2 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell Div. 2008;3:6. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Voorhies WA, Ward S. Broad oxygen tolerance in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. J Exp Biol. 2000;203:2467–78. doi: 10.1242/jeb.203.16.2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nystul TG, Roth MB. Carbon monoxide-induced suspended animation protects against hypoxic damage in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9133–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403312101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller DL, Roth MB. C. elegans are protected from lethal hypoxia by an embryonic diapause. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1233–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carvalho A, Olson SK, Gutierrez E, Zhang K, Noble LB, Zanin E, et al. Acute drug treatment in the early C. elegans embryo. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Encalada SE, Willis J, Lyczak R, Bowerman B. A spindle checkpoint functions during mitosis in the early Caenorhabditis elegans embryo. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:1056–70. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wright AJ, Hunter CP. Mutations in a beta-tubulin disrupt spindle orientation and microtubule dynamics in the early Caenorhabditis elegans embryo. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:4512–25. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-01-0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Massie MR, Lapoczka EM, Boggs KD, Stine KE, White GE. Exposure to the metabolic inhibitor sodium azide induces stress protein expression and thermotolerance in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2003;8:1–7. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2003)8<1:ETTMIS>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCarter J, Bartlett B, Dang T, Schedl T. Soma-germ cell interactions in Caenorhabditis elegans: multiple events of hermaphrodite germline development require the somatic sheath and spermathecal lineages. Dev Biol. 1997;181:121–43. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamamuro D, Uchida R, Takahashi Y, Masuma R, Tomoda H. Screening for microbial metabolites affecting phenotype of Caenorhabditis elegans. Biol Pharm Bull. 2011;34:1619–23. doi: 10.1248/bpb.34.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Budde MW, Roth MB. The response of Caenorhabditis elegans to hydrogen sulfide and hydrogen cyanide. Genetics. 2011;189:521–32. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.129841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller DL, Roth MB. Hydrogen sulfide increases thermotolerance and lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20618–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710191104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sulston JE, Horvitz HR. Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1977;56:110–56. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sulston JE, Horvitz HR. Abnormal cell lineages in mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1981;82:41–55. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90427-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hong Y, Roy R, Ambros V. Developmental regulation of a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor controls postembryonic cell cycle progression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 1998;125:3585–97. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.18.3585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boxem M, van den Heuvel S. lin-35 Rb and cki-1 Cip/Kip cooperate in developmental regulation of G1 progression in C. elegans. Development. 2001;128:4349–59. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.21.4349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fukuyama M, Gendreau SB, Derry WB, Rothman JH. Essential embryonic roles of the CKI-1 cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor in cell-cycle exit and morphogenesis in C elegans. Dev Biol. 2003;260:273–86. doi: 10.1016/S0012-1606(03)00239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fukuyama M, Rougvie AE, Rothman JH. C. elegans DAF-18/PTEN mediates nutrient-dependent arrest of cell cycle and growth in the germline. Curr Biol. 2006;16:773–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baugh LR, Sternberg PW. DAF-16/FOXO regulates transcription of cki-1/Cip/Kip and repression of lin-4 during C. elegans L1 arrest. Curr Biol. 2006;16:780–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baugh LR, Demodena J, Sternberg PW. RNA Pol II accumulates at promoters of growth genes during developmental arrest. Science. 2009;324:92–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1169628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sherr CJ, Roberts JM. CDK inhibitors: positive and negative regulators of G1-phase progression. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1501–12. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang X, Zabinsky R, Teng Y, Cui M, Han M. microRNAs play critical roles in the survival and recovery of Caenorhabditis elegans from starvation-induced L1 diapause. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:17997–8002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105982108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kostić I, Li S, Roy R. cki-1 links cell division and cell fate acquisition in the C. elegans somatic gonad. Dev Biol. 2003;263:242–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mehlmann LM. Stops and starts in mammalian oocytes: recent advances in understanding the regulation of meiotic arrest and oocyte maturation. Reproduction. 2005;130:791–9. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greenstein D. Control of oocyte meiotic maturation and fertilization. WormBook. 2005:1–12. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.53.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hubbard EJ, Greenstein D. Introduction to the germ line. WormBook. 2005:1–4. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.18.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hubbard EJ, Greenstein D. The Caenorhabditis elegans gonad: a test tube for cell and developmental biology. Dev Dyn. 2000;218:2–22. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(200005)218:1<2::AID-DVDY2>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ward S, Carrel JS. Fertilization and sperm competition in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1979;73:304–21. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(79)90069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Collins JJ, Huang C, Hughes S, Kornfeld K. The measurement and analysis of age-related changes in Caenorhabditis elegans. WormBook. 2008:1–21. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.137.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andux S, Ellis RE. Apoptosis maintains oocyte quality in aging Caenorhabditis elegans females. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luo S, Kleemann GA, Ashraf JM, Shaw WM, Murphy CT. TGF-β and insulin signaling regulate reproductive aging via oocyte and germline quality maintenance. Cell. 2010;143:299–312. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mendenhall AR, LeBlanc MG, Mohan DP, Padilla PA. Reduction in ovulation or male sex phenotype increases long-term anoxia survival in a daf-16-independent manner in Caenorhabditis elegans. Physiol Genomics. 2009;36:167–78. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.90278.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Angelo G, Van Gilst MR. Starvation protects germline stem cells and extends reproductive longevity in C. elegans. Science. 2009;326:954–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1178343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jud MC, Czerwinski MJ, Wood MP, Young RA, Gallo CM, Bickel JS, et al. Large P body-like RNPs form in C. elegans oocytes in response to arrested ovulation, heat shock, osmotic stress, and anoxia and are regulated by the major sperm protein pathway. Dev Biol. 2008;318:38–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jud M, Razelun J, Bickel J, Czerwinski M, Schisa JA. Conservation of large foci formation in arrested oocytes of Caenorhabditis nematodes. Dev Genes Evol. 2007;217:221–6. doi: 10.1007/s00427-006-0130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]