Abstract

Although systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multigenic autoimmune disorder, HLA-D is the most dominant genetic susceptibility locus. This study was undertaken to investigate the hypothesis that microbial peptides bind HLA-DR3 and activate T cells reactive with lupus autoantigens. Using HLA-DR3 transgenic mice and lupus-associated autoantigen SmD protein, SmD79–93 was identified to contain a dominant HLA-DR3 restricted T cell epitope. This T cell epitope was characterized by using a T-T hybridoma, C1P2, generated from SmD immunized HLA-DR3 transgenic mouse. By pattern search analysis, 20 putative mimicry peptides (P2–P21) of SmD79–93, from microbial and human origin were identified. C1P2 cells responded to SmD, SmD79–93 and a peptide (P20) from Vibro cholerae. Immunization of HLA-DR3 mice with P20 induced T cell responses and IgG antibodies to SmD that were not cross-reactive with the immunogen. A T-T hybridoma, P20P1, generated from P20 immunized mice, not only responded to P20 and SmD79–93, but also to peptides from Streptococccus agalactiae (P17) and human-La related protein (P11). These three T cell mimics (P20, P11 and P17) induced diverse and different autoantibody response profiles. Our data demonstrates for the first time molecular mimicry at T cell epitope level between lupus-associated autoantigen SmD and microbial peptides. Considering distinct autoreactive T cell clones, activated by different microbial peptides, molecular mimicry at T cell epitope level can be an important pathway for the activation of autoreactive T cells resulting in the production of autoantibodies. In addition, the novel findings reported herein may have significant implications in the pathogenesis of SLE.

Keywords: Epitope, HLA-DR3, Mice, Molecular Mimicry, Systemic Lupus, Erythematosus, SmD

1. Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multigenic autoimmune disease with diverse clinical manifestations at the initial diagnosis and subsequent relapses [1, 2]. SLE is characterized by the presence of autoantibodies to a number of cellular antigens, including dsDNA, phospholipids and several ribonucleoproteins [3, 4]. Susceptibility to SLE is dependent on both genetic and environmental factors. Family studies show there is a significant genetic influence in SLE [5]. The genetic element that exerts the most influence is the HLA-D region [6–9]. Genetic predisposition to SLE manifests into several cellular defects such as: hyperactivity at T and B cell level [10]; defective clearance of apoptotic cells [11]; regulatory T cell defects [12] and Toll-like receptor driven autoantibody production [13]. However, these defects do not explain the strongest association of SLE with HLA-D.

The present study was designed to investigate the mechanisms responsible for the dominant role of HLA-DR in the pathogenesis of SLE. It was hypothesized that HLA-DR influences the selection and enrichment of autoreactive T cells that provide cognate help to B cells recognizing the same autoantigen. One plausible pathway for the activation and enrichment of these autoreactive T cells is through the presentation of molecular mimics. This pathway is eminently feasible in view of the well established facts that positive selection of CD4+ T cell repertoire is based on self MHC Class II molecules and those TCRs are polyreactive [14]. While the role of molecular mimicry at T cell epitope level in initiating autoimmune responses has been explored in various autoimmune disease such as multiple sclerosis, evidence for it in SLE is still lacking. Thus, in this investigation, HLA DR3 transgenic mice were used as an experimental model system, as HLA-DR3 is strongly associated with SLE [7, 15]. SmD protein, which is a part of the small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (snRNP) complex and is involved with the splicing and processing of pre-mRNA was selected as the model autoantigen [16]. Antibodies against SmD are seen in lupus patients in North America [17] and the presence of anti-Sm antibodies is one of the classification criteria for SLE as established by the American College of Rheumatology [18]. In addition, mouse SmD is completely homologous to human SmD, thereby rendering it to be an ideal autoantigen.

In this study, we identified a dominant DR3 restricted T cell epitope on SmD79–93 and mimicry peptides capable of activating T cells reactive with this epitope. SmD79–93 and its molecular mimics induced autoantibodies against SmD and other lupus-related autoantigens. These data provide a mechanism for association of specific HLA-D haplotypes with SLE and demonstrate the potential of T cell epitope mimicry, for initiating autoimmune responses in SLE. They suggest that autoimmune responses in SLE may be initiated through multiple exposures to environmental antigens over a long period.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthetic peptides and recombinant proteins

Synthetic peptides (20mers with 15 amino acids overlap) spanning the entire sequence of mouse SmD1 protein (aa1-119) and 15mer peptide mimics were obtained from the core facility of Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN). 15mer peptides with a 12 amino acid overlap were obtained from the Biomolecular Research Facility at the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, VA). All peptides were HPLC purified and were >90% pure. Peptides with alanine substitutions were synthesized on pin supports using the Multipin Cleavable Peptide kit (Chiron Mimotope Technologies, Australia). The cloning, expression, and purification of recombinant SmD (rSmD), mouse Ro60 (mRo60), and Derp2 proteins has been previously described [19].

2.2. Mice and immunizations

All mouse experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of Virginia and Mayo Clinic. The HLA-DRB1*0301, HLA-DRA1*0101 (DR3) transgenic (tg) mice; DR3.Aβ0/0 and DR3.E0/0 have been previously described [20, 21]. Mice were housed in specific pathogen-free conditions at either the Mayo Clinic or the University of Virginia vivarium. For T cell mapping studies, mice were immunized in the left footpad and base of tail with 100µg of rSmD emulsified in IFA or IFA alone. For antibody generation, mice (n=5 per group) were immunized in the left footpad and base of tail with 100µg of peptide emulsified in CFA. On days 14 and 28 post-immunization, mice received additional injections of 50µg of peptide emulsified in IFA by intraperitoneal route. Sera were collected at monthly time points and stored at −20°C.

2.3. T cell epitope mapping and T-T hybridoma generation

T cell epitope mapping was performed as described previously [22]. Culture supernatants were screened for IFN-γ and IL-5 production by ELISA kits (BD Pharmingen). Cells from wells showing high IFN-γ production were fused with TCR−/− variant BW5147 as described before [22]. T-T hybridomas against the Vibrio peptide were generated similarly using T cells from mice immunized with P20. Reactivity of T-T hybridomas (1 × 105 cells) to synthetic peptides or recombinant proteins was determined by incubating hybrids with syngeneic spleen cells (5 × 105 cells) fed with or without antigen for 16–18 hours. Culture supernatants were screened for IL-2 production by an ELISA kit (BD Pharmingen). Selected T-T hybridomas were cloned twice by limiting dilution method.

2.4. Antibody analysis

Reactivity of antibodies to synthetic peptides and rSmD was measured by ELISA as described previously [19, 22]. The autoantibody profile of sera from immunized mice was determined by Western blot [19, 21]. Anti-dsDNA antibodies were determined as described [23, 24], using plasmic DNA as the substrate. Monoclonal antibody R4A was used to construct a standard curve and data are presented as ng/ml of anti-dsDNA antibodies. R4A was kindly provided by Dr. Betty Diamond. Antibody reactivity to native SmD protein was determined by immunoprecipitation assay using in vitro translated and 35S-radiolabeled SmD protein [22]. Detection of radioactivity associated with the immunoprecipitated product was quantified by liquid scintillation counting. Results are expressed as ratio of CPM from beads with sera to CPM from beads with no sera. Cross-reactivity of anti-peptide antibodies with SmD was determined by depleting sera of anti-peptide antibodies with peptide coupled-sepharose beads [22]. ANA was determined using HeLa cells as the substrate [25]. The autoantibodies assays were designed to detect IgG isotypes since the secondary antibodies were anti-mouse IgG.

2.5. Analysis of TCR usage

TCR-Vβ usage by T-T hybridomas was determined with a TCR-Vβ screening panel containing FITC-conjugated monoclonal antibodies to various mouse TCR Vβ (BD Pharmingen CA) by flow cytometry using a BD FACSscan analyzer and data analysis was carried out using Flow Jo software (Tree Star). For sequencing the TCRs, first strand cDNA synthesis was carried out using Superscript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, CA) from RNA extracted from T-T hybridomas using RNeasy Kit (Qiagen). The cDNA was amplified as described by Chen et al. [26]. PCR products were then cloned into a pT7blue vector and sequenced at the University of Virginia Sequencing Core.

2.6. Enrichment of SmD reactive T cell line and proliferation assay

HLA-DR3 mice were immunized either with P20 emulsified in CFA or only CFA. Draining LNC’s and spleen cells were harvested and cultured with 30µg/ml of rSmD protein for three days (5 × 106 cells/ml). After 3 days cells were washed twice and rested in medium supplemented with rhIL-2 (10U/ml) for 7 days. Live cells were obtained following Ficoll density gradient centrifugation and used in proliferation assays. T cells (1 × 105) were cultured with irradiated syngeneic spleen cells (5 × 105) in the presence or absence of antigen in 96 well plates in triplicates for 4 days. Cells were pulsed with 3H-thymidine (1µCi/well) during the last 14 hours of culture. The cells were harvested onto glass fiber filters and radioactivity measured by using a Betaplate counter.

3. Results

3.1. Mapping of DR3 restricted T epitopes on SmD

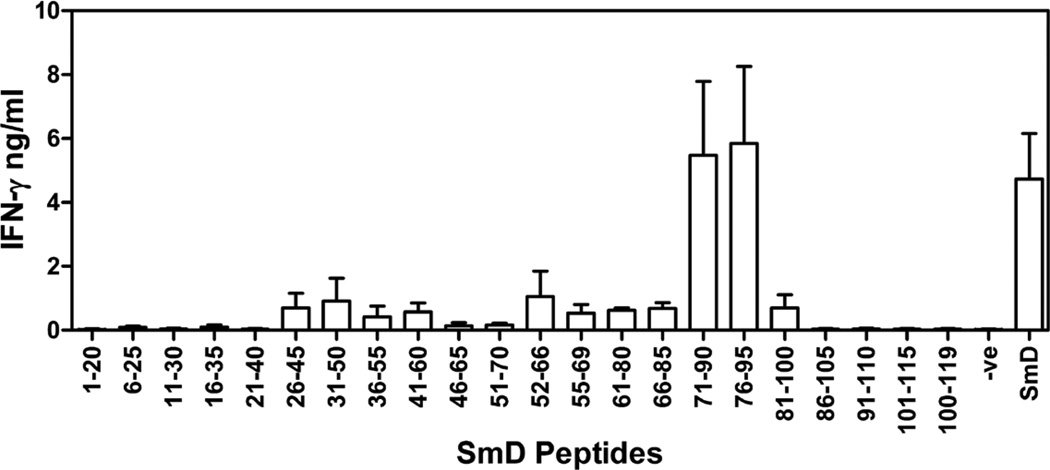

To map the T cell epitopes on SmD, HLA-DR3 transgenic mice were immunized in the footpad with rSmD and 10 days later draining lymph node cells were stimulated in vitro with overlapping peptides spanning the entire region of SmD. After 40–44 hours of incubation, IFN-γ production was measured by ELISA and results from 3 independent experiments are shown in figure 1. Peptides within regions 71–95 were able to elicit highest levels of IFN-γ production, indicating their immunodominance. Lymph node cells recovered from mice immunized with IFA alone and stimulated with overlapping peptides of SmD did not produce IFN-γ. Since peptides within region 71–95 gave the highest stimulation, further studies were focused within this region.

Figure 1. Mapping of T cell epitopes on SmD.

Draining lymph node cells from HLA-DR3 mice immunized with rSmD were stimulated with overlapping synthetic peptides spanning SmD protein for 40–44 hrs. Culture supernatants were used for IFN-γ measurement by ELISA. Data is represented as mean cytokine ± SEM (pg/ml) from three independent experiments.

3.2. Identification of SmD81–88 as the core T cell epitope and the identification of peptide mimics of SmD79–93

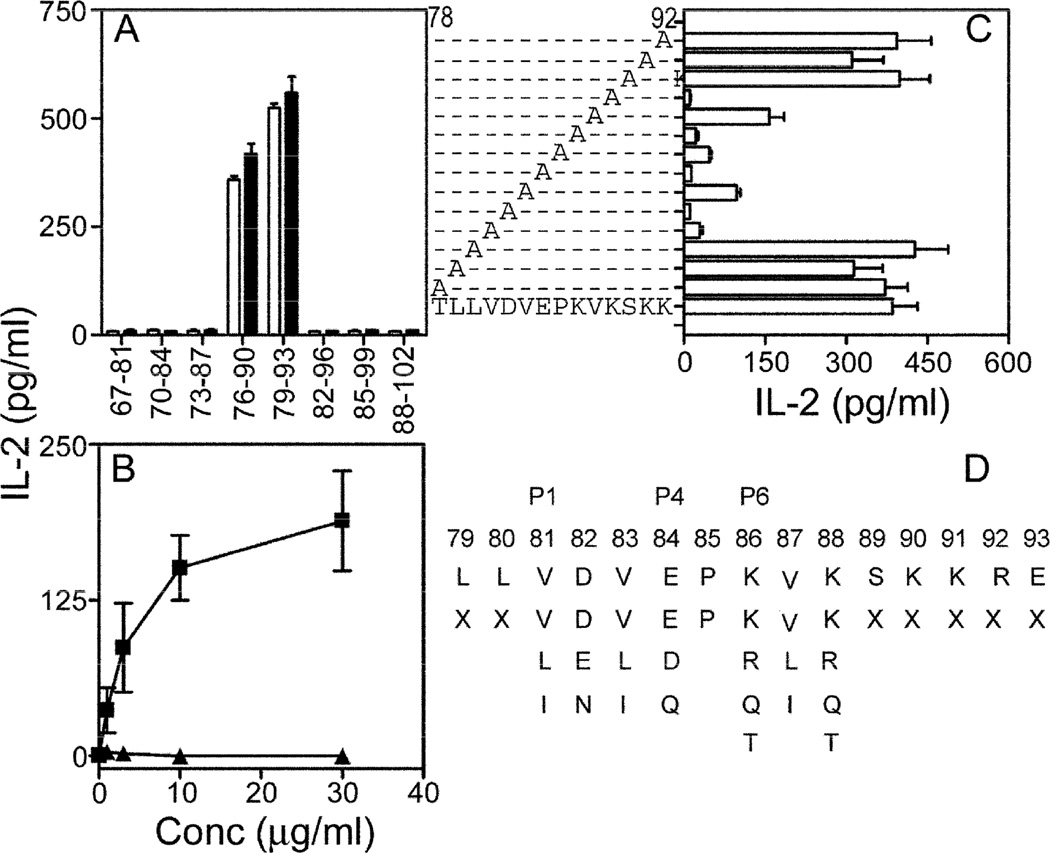

To map the core T-epitope on SmD71–95, T-T hybridomas were generated from mice immunized with rSmD and selected for reactivity against peptides SmD71–90 and SmD76–95. One of the T-T hybridomas, C1P2 responded to SmD76–90 and SmD79–93 (figure 2A). Antigen presenting cells from both DR3.Aβ0/0 and DR3.E0/0 mice were able to present these peptides and activate C1P2, thereby demonstrating the DR3 restriction of this epitope. The only Class II molecule expressed in DR3.E0/0 mice is DR3 [20]. The DR3 restriction was further confirmed in that CIP2 responded well to SmD79–93 presented by DR3/DQ2 homozygous EBV-transformed cells (figure 2B).

Figure 2. Characterization of the dominant T cell epitope SmD79–93.

A. T-T hybridoma C1P2 was activated by peptides SmD76–90 and SmD79–93, presented by spleen cells from either DR3.E0/0 (□) or DR3.Aβ0/0 (■) mice. B. C1P2 cells are activated by SmD79–93 (■) presented by HLA-DR3+ EBV transformed B cell line QBL. Control peptide P21 (▲, sequence shown in Table 1) did not activate C1P2. C. To map critical amino acid residues, alanine substituted peptides were used to activate C1P2 using DR3.E0/0 spleen cells. Data (A–C) are represented as mean IL-2 ± SEM (pg/ml) from at least two independent experiments. D. Search pattern used to probe the database is shown. P1, P4 and P6 represent HLA-DR3 anchor residues. X denotes any amino acid.

The core residues were mapped using a panel of alanine substituted peptides (figure 2C). Alanine substitution at residues 81(V), 82(D), 83(V), 84(E), 85(P), 86(K), 87 (V), 88 (K) significantly abrogated IL-2 production by C1P2. Based on the known DR3 binding motifs [27], in which a hydrophobic amino acid is located in the first position n, a hydrophobic amino acid in position n + 2, a hydrophilic amino acid in position n + 3, and a positively charged amino acid in position n + 5, it is inferred that amino acids 81 (V), 83 (V), 84 (E), and 86 (K) are responsible for MHC class II binding while amino acids 82 (D), 85 (P), 87(V), 88(K) are involved in TCR contact.

To identify the peptide mimics of SmD79–93, a pattern search was performed using tools available at http://pir.georgetown.edu/pirwww/search/pattern. The search parameters are shown in figure 2D and the amino acid substitutions at critical positions 81–88 were based on the recommendation by Bordo and Argos [28]. This strategy identified 417 peptides and 40 peptides related to human pathogens or self-antigens were selected for further analysis. HLA-DR binding algorithm [29] showed that 20 peptides had a DR3 binding motif. The peptides, proteins, and organisms from which they are derived are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

20 putative peptide mimics (peptide 2-peptide 21) of SmD79–93.

| Peptide | Sequence | Protein (Species) | Accession # |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LLVDVEPKVKSKKRE | SmD 79–93 (Homo sapiens) | P62314 |

| 2 | ESLNLDPRLRQALIK | RNA helicase 60–74 (Aspergillus fumigatus) | XP_755731 |

| 3 | NIINLQPKLQAARVA | CoaD 442–456 (Bacillus coagulans) | AAG28766 |

| 4 | APLEIDPRLREIDFG | phosphoglycerate mutase 73–87 (Burkholderia mallei) | YP_102462 |

| 5 | NYLEVDPTVREGALS | lactone regulator 70–84 (Burkholderia mallei) | YP_105961 |

| 6 | WDLELDPQIRTNRGF | periplasmic protein 213–227 (Campylobacter jejuni) | NP_282399 |

| 7 | YLLDLEPQIKGGSKE | ABC transport protein 318–332 (Campylobacter jejuni) | NP_281964 |

| 8 | ASLELDPKVRTIIEI | activator of dehydratase 88–102 (Clostridium tetani) | NP_781145 |

| 9 | NIIEIEPKLTINQLL | DNA mismatch repair protein 548–562 (Entamoeba histolytica) | XP_651821 |

| 10 | CTVNLDPKLREIIAD | kinase D-interacting of 220 kDa 1050–1064 (Homo sapien) | NP_065789 |

| 11 | KNLDIDPKLQEYLGK | La-related protein 1 926–940 (Homo sapien) | NP_056130 |

| 12 | LALEIDPTVQRVKRD | Type 2 hair keratin 2 105–119 (Homo sapien) | NP_149022 |

| 13 | VSVEVDPKVTELPPI | Mitogen activated kinase 440–454 (Leishmania major) | XP_001469647 |

| 14 | KLIEIDPTLQIDMPQ | Tyrosine recombinase XerD 91–105 (Pseudomonas fluorescens) | YP_258232 |

| 15 | IGLDIDPQVQVLRLA | decarboxylase 144–158 (Pseudomonas syringae) | YP_234921 |

| 16 | DILELDPRLKLCAIR | Glycerate kinase 175–189 (Salmonella enterica) | YP_218181 |

| 17 | EIVDLDPKLKQINLI | TcmP methyltransferase 215–229 (Streptococcus agalactiae) | NP_688496 |

| 18 | QQLEVDPKIKAETAF | Monooxygenase 93–107 (Trypanosoma cruzi) | XP_805876 |

| 19 | PALELDPKLTTPLLR | Monoglyceride lipase 164–178 (Trypanosoma cruzi) | XP_805120 |

| 20 | LDIDIDPKVKVATLS | Galactoside ABC transporter 145–159 (Vibrio cholerae) | NP_230971 |

| 21 | SLIEIQPRLTSALEQ | ATP-dependent protease LA-related 79–93 (Vibrio cholerae) | NP_231123 |

3.3. CIP2 is activated by a peptide from the galactoside ABC transporter protein in Vibrio cholerae

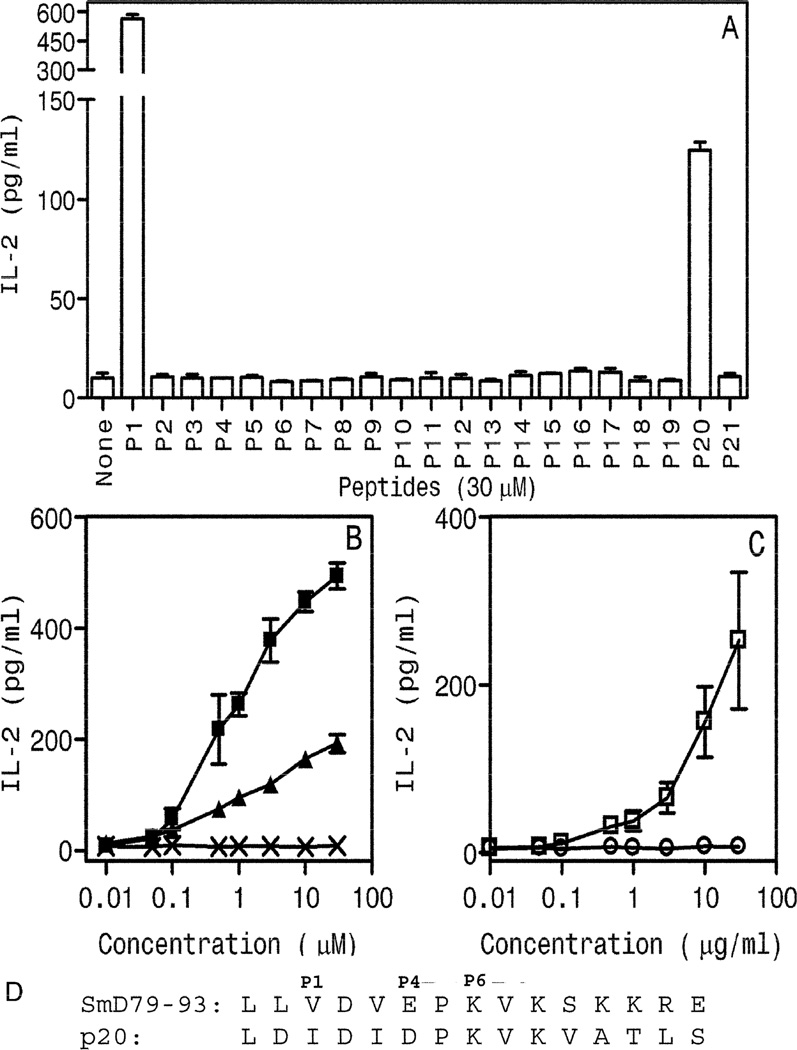

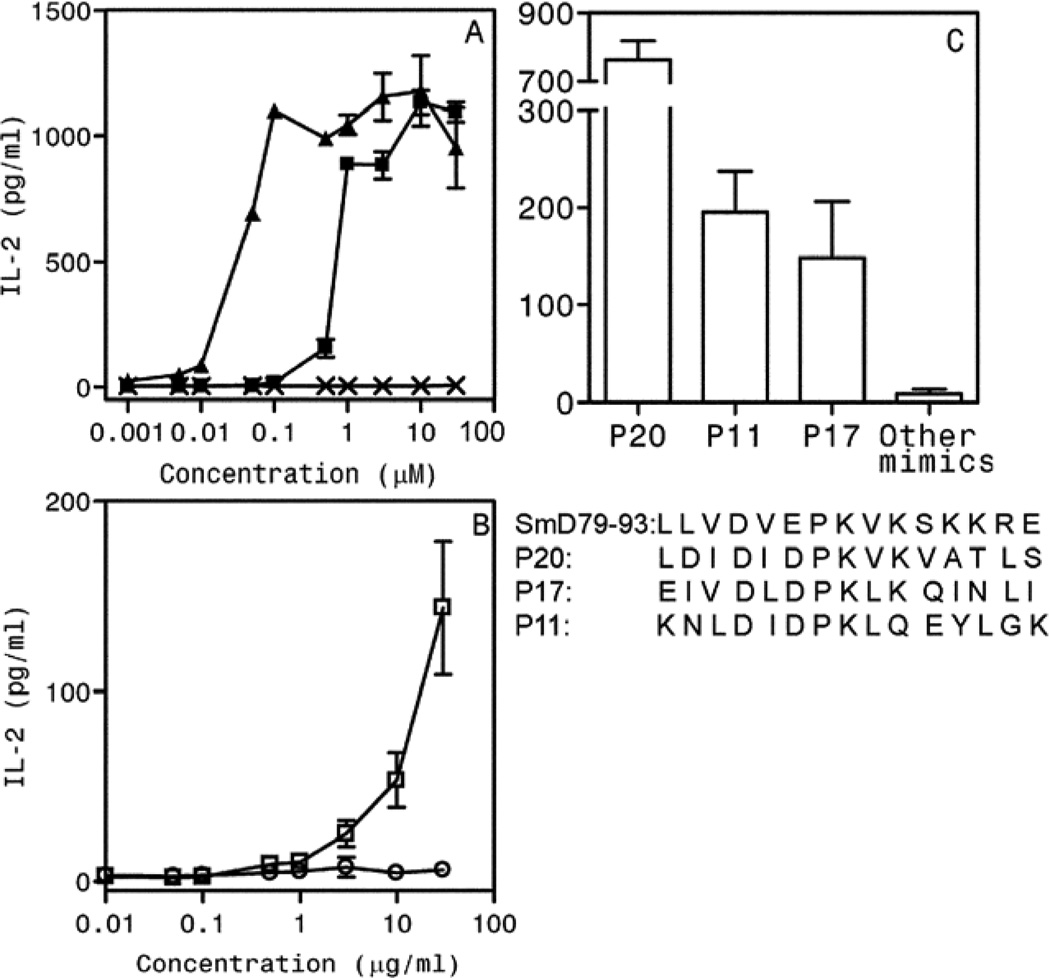

Of the 20 mimics tested, only Peptide 20 (P20), from galactoside ABC transporter protein in Vibrio cholerae, was able to induce IL-2 production (figure 3A). However, the level of induced IL-2 was much lower than the parent peptide SmD79–93 (labeled as P1). This was further confirmed by performing a dose response curve (figure 3B). The sequences of both peptides and their putative MHC anchor residues are shown at the bottom of the panel (figure 3D). To determine whether C1P2 is activated by SmD, C1P2 cells were incubated with spleen cells from DR3.E0/0 mice and different concentrations of rSmD. IL-2 production was induced by rSmD but not by recombinant mouse Ro60 protein (figure 3C). Control peptide mimic P21 and recombinant mouse Ro60 protein did not induce any IL-2 production over the background.

Figure 3. A synthetic peptide aa145-aa159 (P20) from Vibrio cholerae, galactoside ABC transporter protein is a T cell epitope mimic of SmD79–93.

A. C1P2 responded to SmD79–93 (P1) and P20 but not to the other 19 peptides (P2–P19 and P21, sequences shown in Table 1). C1P2 cells were activated in a dose dependent fashion by SmD79–93(■), P20 (▲) (B) and rSmD (□) (C) but not by control peptide, P21(X) (B) or rmRo60(○) (C). Data are represented as mean IL-2 ± SEM (pg/ml) from at least two independent experiments. D. Comparison of amino acid sequences of SmD79–93 and P20. P1, P4 and P6 represent possible HLA-DR3 anchor residues.

3.4. Induction of autoantibodies and T cell responses to SmD in DR3 mice immunized with mimic P20

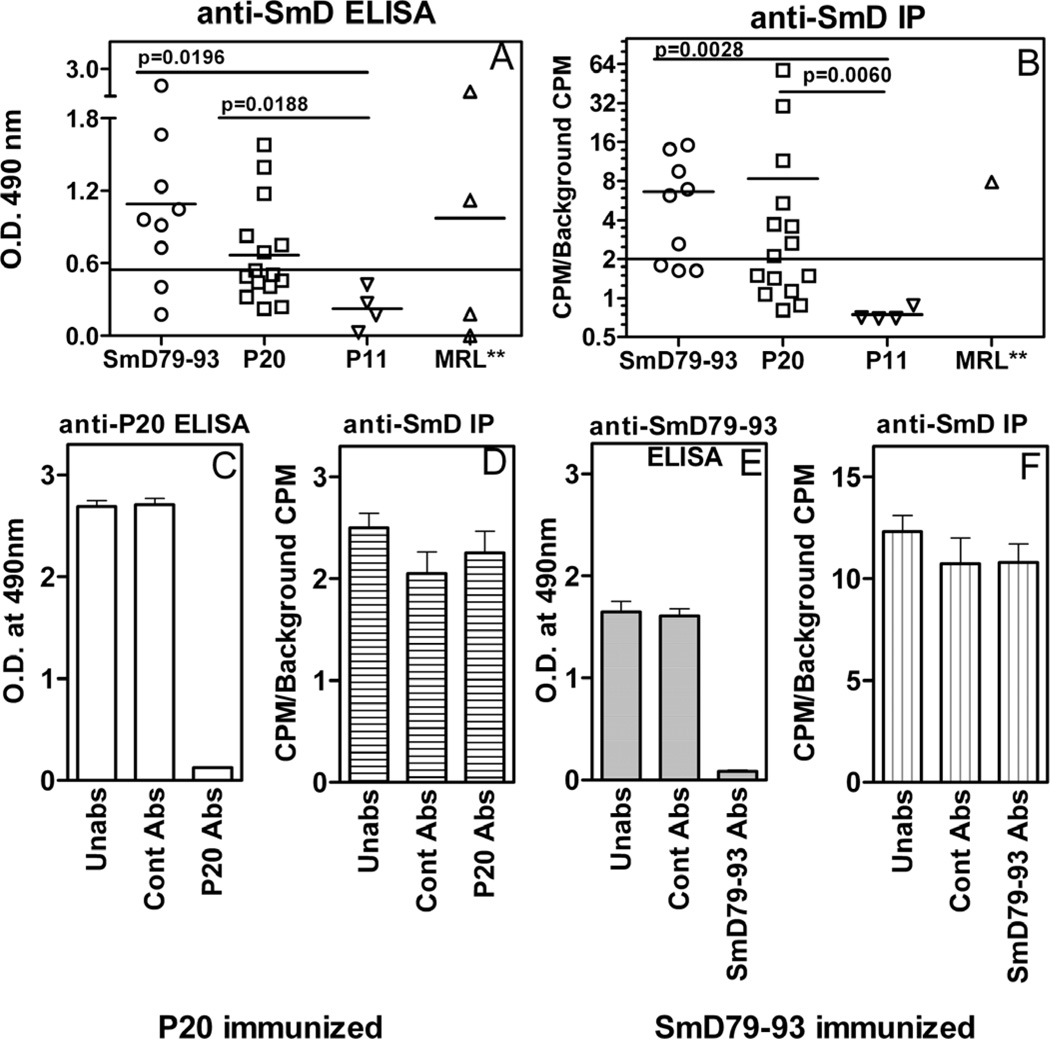

DR3 transgenic mice immunized with P20, generated antibody responses to P20 and to SmD (figure 4). Both ELISA and immunoprecipitation were used. By both assays (figure 4), approximately 70 % of the mice made anti-SmD antibodies when they were immunized with either P20 or SmD79–93. The proportions of responding mice were similar to that when the immunogen was the recombinant SmD protein (23). Although it appeared that more potent response to SmD was observed in the group of mice immunized with SmD79–93 when ELISA was used (figure 4A), this differences was not statistically significant. The anti-SmD antibody responses were significantly higher in thes two groups of mice when they were compared to that mounted by anti-P11 immunized mice. Similar results were obtained when Immunoprecipitation was carried out to ascertain anti-SmD antibody response in the three groups of immunized mice.

Figure 4. Induction of anti-SmD antibody responses in HLA-DR3 transgenic mice by P20.

Individual sera from mice immunized with SmD79–93 and P20 were assayed for antibodies against SmD by ELISA (A) and Immunoprecipitation (B). In ELISA, recombinant SmD was used as the substrate and sera were assayed at 1;100 dilutions. Three MRL/lpr female mice at ages 5–8 months awere used as positive control sera. For Immunoprecipitation, in vitro translated S35 labeled SmD was used as the antigen in Immunoprecipitation. Pooled sera from mice immunized with P20 (C and D) or SmD79–93 (E and F) were absorbed with Sepharose beads (Con Abs) or immunogen coupled Sepharose beads (P20 Abs or SmD79–93 Abs) or were untreated (Un). The sera were then assayed for antibody reactivity to the immunizing peptides by ELISA (P20 in C and SmD79–93 in E) or to SmD by immunoprecipitation (D and F).

Because the immunized mice made antibodies to both immunizing peptides and SmD, the possibility that anti-peptide antibodies are cross-reactive with SmD was entertained. Despite depleting anti-peptide antibodies by P20-coupled Sepharose beads (figure 4C), the reactivity of the absorbed sera against SmD, as seen by their ability to immunoprecipitate in-vitro transcribed and translated 35S-SmD was not diminished (figure 4D). Similarly, absorption of pooled sera with control beads did not significantly alter the reactivity against SmD. Similar results were obtained with sera from mice immunized with SmD79–93 (figures 4E and 4F). Although not shown, similar results were obtained when anti-SmD antibodies were assayed by ELISA. These data indicate that the vast majority, if not all, of antibodies generated against SmD following immunization with mimic peptide, P20 are non-cross reactive with the immunogens.

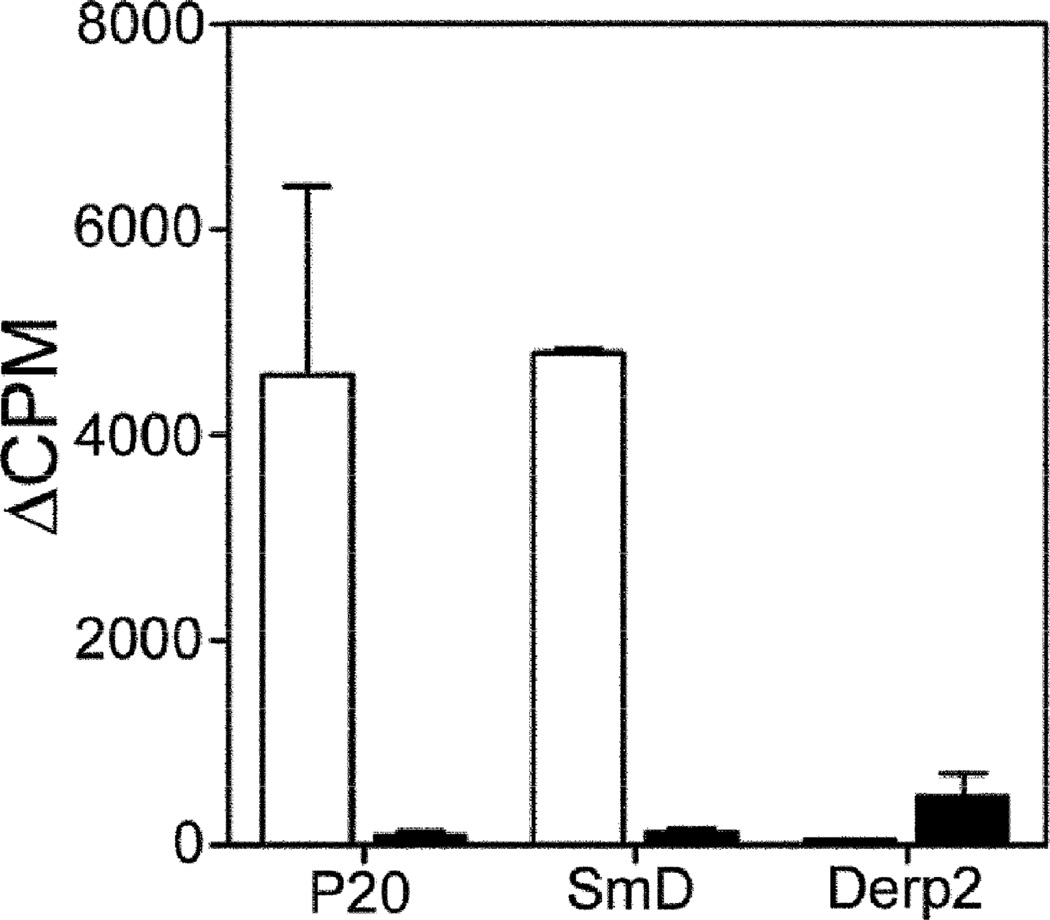

Minimal cross-reactivity between anti-P20 antibodies and anti-SmD antibodies suggest that a T cell response against SmD was generated in P20 immunized mice. Figure 5 demonstrates proliferative responses to P20 and SmD in T cells obtained from P20 immunized mice. These responses were not seen in T cells enriched from CFA immunized mice. However, some proliferative response to recombinant DerP2 was observed in T cells enriched from adjuvant-immunized mice.

Figure 5. T cells obtained from P20 immunized mice show reactivity to P20 and SmD.

Short term T cell lines were generated against SmD from mice immunized either with P20 (□) or CFA (■). The short term T cell line responded to rSmd (100µg/ml), and P20 (30µM), but not to Derp2 (100µg/ml). Data are represented as ΔCPM ± SEM from two independent experiments. ΔCPM was calculated as CPM with antigen-CPM without antigen.

To further confirm the activation of SmD-reactive T cells induced by immunization with P20, T-T hybridomas were generated from P20 immunized mice and screened for their reactivity to SmD. One representative T-T hybridoma P20P1, showed reactivity to P20, and SmD79–93 (figure 6A) as well as to rSmD (figure 6B) in a dose response manner. However, in contrast to C1P2 activation, P20 was more potent in activating hybridoma P20P1.

Figure 6. Characterization of T-T hybridoma P20P1 derived from DR3 mouse immunized with mimicry peptide P20.

A. P20P1 is activated in a dose dependent fashion by SmD79–93 (■), and P20 (▲), but not by P21 (X). (B) P20P1 responded to rSmD (□) but not to mrRo60 (○). Data are represented as mean IL-2 ± SEM from at least two independent experiments. (C) Hybridoma P20P1 is also activated by additional mimics P11 and P17. The sequences of all peptides are shown for comparison.

Screening of hybridoma P20P1 with the panel of molecular mimics (Table 1) was undertaken to see if additional mimics could activate this hybridoma. As seen in figure 6C, P11 (peptide 926–940 from human La-related protein) and P17 (peptide 215–229 from TcmP methyltransferase from Streptococcus agalactiae) were capable of stimulating hybridoma P20P1. The responses to P11 and P17 by P20P1 were considerably less vigorous than that to P20.

To determine whether TCR usage dictated the reactivity patterns of C1P2 and P20P1, the TCRs from these hybridomas were identified. C1P2 was stained by an anti-Vβ 8.3 antibody and P20P1 by an anti-Vβ 8.1 antibody. The Vβ and Vα regions from both hybridomas were cloned and sequenced and the data is summarized in Table 2. These data show that a polyclonal T cell response is generated against the SmD79–93 region and the ability of different molecular mimics to activate these T cells is influenced by their TCR usage (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hybridomas C1P2 and P20P1 react with different antigens and use different TCRs.

| Hybridoma | Immunogen | Reactivity | Vα | Vβ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1P2 | SmD | SmD, SmD79–93, P20a | TRAV6D-7*04; TRAJ43*01 |

TRBV13-1*02; TRBD1*01; TRBJ1-1*01 |

| P20P1 | P20 | SmD, SmD79–93, P20, P11b, P17c |

TRAV12D-2*02; TRAJ16*01 |

TRBV13-3*01; TRBD2*01; TRBJ2-5*01 |

Galactoside ABC transporter 145–159 (Vibrio cholerae);

La-related protein 1 926–940 (Homo sapien);

TcmP methyltransferase 215–229 (Streptococcus agalactiae).

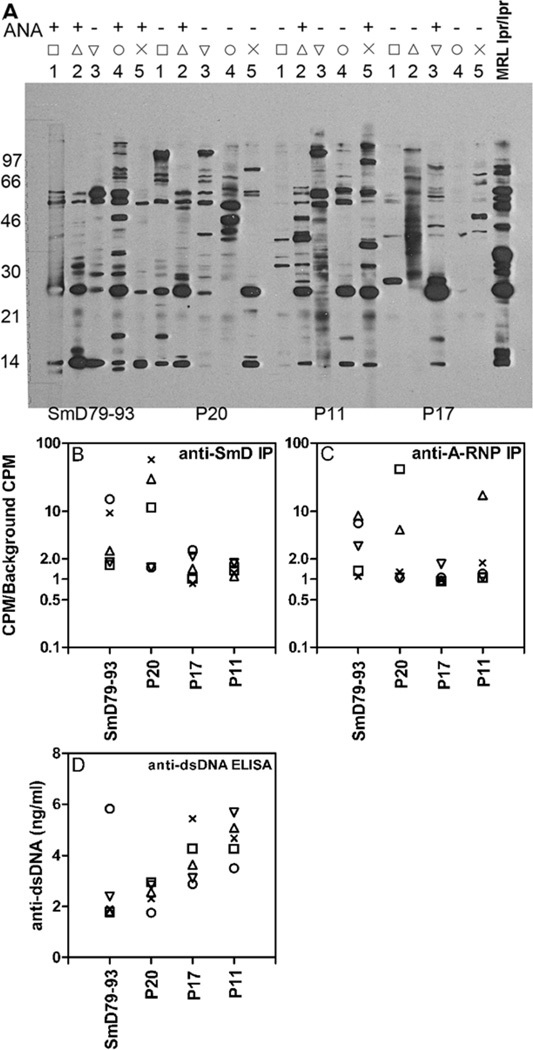

3.5. Immunization of HLA-DR3 mice with additional mimics of peptide SmD79–93 induce antibodies against different autoantigens

As shown in figure 3, SmD79–93 and its mimic P20 induced anti-SmD autoantibodies. To determine whether autoantibodies of other specificities are also induced, DR3 mice were immunized with additional peptide mimics (P11 and P17). The results presented in figure 7 were from four groups of DR3+ female mice of similar ages and immunized with the four peptides at the same time.

Figure 7. Immunizations of HLA-DR3 mice with SmD79–93 and three mimicry peptides generate anti-SmD and other lupus-related autoantibodies.

D60 post-immunization sera from individual HLA-DR3 mice immunized with SmD79–93, P20, P17 and P11 were analyzed for reactivity to lupus-related autoantigens by immunofluorescence (ANA) and Western blotting (A); by immunoprecipitation of in vitro translated SmD (B) and A-Ribonucleoprotein (A-RNP) (C); and by ELISA to dsDNA (D). A. (upper panel) indirect immunofluorescence was used to determine ANA activity with individual sera diluted at 1:50 with HeLa cells as the substrate. Lower panel: Autoantibody profiles for groups of five HLA-DR3 mice immunized with P20, SmD79–93, P11, or P17 by Western blot. Positive control pooled sera (+) were from MRL/lpr mice. B and C. 35S labeled in vitro translated SmD and A-RNP were precipitated with each immune sera. Data are expressed as ratio of CPM with immune sera to CPM with no sera. A ratio of >2.0 was considered positive. Similar results were obtained in 2 additional cohorts of mice. D. Anti-dsDNA antibodies were assayed at a 1:50 serum dilution and data are represented as mean ng/ml antibodies of duplicates with R4A monoclonal antibody to dsDNA as the reference. In figures B, C, and D, each mouse is represented by a symbol and corresponds to individual sera in each group used in the Western blot analysis.

By Western blot analysis, with a cell lysate from a mouse lymphoma cell line as the substrate, most immune sera showed reactivity with multiple bands (figure 7a). As expected, sera from mice immunized with SmD79–93 had reactivity against SmD and the A-RNP (figures 7B and 7C). Also, four out of five immune sera were positive for antinuclear antibodies (ANA). Similar reactivities were found with the P20 immune sera although only one of the five sera was positive for ANA. The ANA staining was coarse speckled (data not shown). The staining pattern may suggest ANA staining by anti-SmD antibodies. The sera from mice immunized with P17 were much weaker in all these antibody activities. However, antibodies against SmD and the A-RNP were definitely induced in some of the mice. The immune sera from P11 immunization did not react with SmD and only one out of five mice had anti-A-RNP antibodies. However, P11 and P17 immune sera were more reactive with dsDNA (figure 7D). Similar results were obtained in an additional experiment.

4. Discussion

Despite exhaustive genetic studies, why the HLA-D region remains the highest risk factor for development of SLE remains unanswered. The results of the present study provide a plausible mechanism for this observation. In this study, using SmD as a SLE-related antigen, three HLA-DR3 restricted T cell epitope mimics of SmD were identified: Galactoside ABC transporter protein aa145–aa159 in Vibrio cholerae, TcmP methyltransferase aa215–aa229 in Streptococcus agalactiae and La-related protein 1 aa926–aa940 in human. Two out of three mimics induced an immune response against SmD and all mimics induced autoantibodies. Two of these mimics come from microbes. To our knowledge, these results provide the first experimental evidence for the role of T cell epitope mimicry in the context of HLA-DR3 restriction for initiating autoantibody responses against SLE-related antigen.

It is of interest to note that the autoantibodies generated with different mimics have diverse specificities. This diverse patterns of autoantibody specificities underlies the difficulties in determining the genetic linkage of specificities loci to autoantibody specificities in SLE and it is also difficult to ascertain the origins of antigenic stimulation leading to a population of autoantibodies. In this regard, the anti-dsDNA antibody response to P11 exemplifies these difficulties.

SLE has traditionally been considered a B cell disease with autoantibodies as a major pathogenic factor. Thus, studies on molecular mimicry in SLE have mainly focused on B cell epitopes. Amongst these, association between anti-EBV antibodies and lupus-associated antigens have been scrutinized the most [30]. Immunization of New Zealand white rabbits with the EBNA-1 peptide mimicking a B cell epitope on Ro60 induced antibodies against EBNA-1 and Ro60 [31]. However, the role of T cell responses was not considered in this study. Relevant to this discussion, Putterman and Diamond identified a peptide mimotope of a nephritogenic anti-DNA mouse monoclonal antibody [32]. Immunization of BALB/c mice with this mimotope in a multiple antigenic peptide (MAP™) format induced anti-DNA antibodies. The induction of anti-DNA was shown to be dependent on T cell reactivity to a foreign epitope created in the mimic peptide linked MAP™ [33]. Thus it is likely that studies showing EBV B cell epitope-induced antibodies against SLE-related antigen are dependent on T cell responses to a foreign epitope in the immunogen. The present study differs significantly from those cited above in that the activation of autoreactive T cells by the molecular mimics is sufficient to initiate an anti-SmD and related autoantibody response. The anti-SmD autoantibodies generated were not cross-reactive with the immunogen. Thus, the anti-SmD antibodies in the immunized mice were generated through the interaction of SmD reactive T cells activated by the molecular mimic and B cells reactive with endogenous SmD. Further autoantibody diversification against the A-RNP, dsDNA and nuclear antigens results from intermolecular epitope spreading. This scenario is very similar to T cell epitope mimicry in autoantibody induction in an experimental model of anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) disease in rats. Immunization of rats with peptide mimics of a single nephritogenic T cell epitope induced anti-GBM antibodies without developing antibodies against the T cell epitope itself [34].

Recent studies have demonstrated that patients heterozygous for HLA-DR2 or homozygous for HLA-DR3 appear to be more susceptible for developing antibodies against Sm proteins [15]. Since HLA dictates the T cell repertoire against a self antigen, identifying HLA-DR3 restricted T cell epitopes is an important step towards identifying relevant molecular mimics. Although previous studies in SLE patients have mapped T cell epitopes on SmD within amino acids 83–119 [35], 35–53 and 53–67 [36], molecular mimics for these epitopes have not been defined. The studies by Talken et al [36] showed that these T cell epitopes were DR3 restricted. The T cell epitopes mapped in the present study fall within the same regions recognized by human T cells, thereby demonstrating the relevance of using HLA-DR3 transgenic mice as an experimental mouse model system. However, the ability of the peptide mimics to activate T cells from SLE patients and in normal individuals needs to be investigated.

There is mounting experimental evidence that supports a role for molecular mimicry in the induction and/or perpetuation of autoimmune responses [37 and reviewed in 38]. Although a case report of a patient presenting concurrently with a Vibrio infection and SLE has been published [39], we cannot generalize that Vibrio infection can initiate autoimmune responses in SLE. Based on the methodology employed in this investigation, we have underestimated the number of peptide mimics that can activate SmD reactive T cells. Characterization of just 2 hybridomas reactive with SmD79–93 showed that they were activated by different peptide mimics and this property was dictated by their different TCR usage (Table 2). Considering a possibility that additional T cells can recognize this region, and that there are other T cell epitopes on SmD, a wide range of mimicry peptides hold the potential to activate SmD reactive T cells Extrapolating this scenario to several other autoantigens that are targeted in SLE, suggests that a vast array of mimics and thereby microorganisms can activate self-reactive T cells. Clearly this makes the task of associating a single microorganism/infection with SLE an ineffectual exercise. Based on our data, we propose a hypothesis that in individuals genetically susceptible for development of SLE, repeated exposure to multiple molecular mimics is responsible for enriching their autoreactive T cell repertoire. Additional genetic defects then contribute towards the induction and perpetuation of autoimmune responses in SLE. This hypothesis has been schematically depicted in a recent review [40]. This thesis is also supported by studies in multiple sclerosis. Recently, Harkiolaki et al [41] demonstrated that multiple peptides from different microorganisms were capable of activating HLA-DR2 restricted transgenic T cells that were reactive with myelin basic protein peptide 85–99. Due to the presence of the same cross-reactive peptides in multiple microorganisms it was concluded that it would be difficult to incriminate individual infections in the development of MS.

Recently there has been a renewed interest and appreciation for the role of human microbiota in the shaping of immune system [42]. Germfree mice have several immunological defects, and some of the autoimmune disorders in these mice show considerable deviation, when compared to mice maintained in specific pathogen free conditions [43]. With respect to SLE models, development of autoimmunity in germfree MRL-lpr mice was construed as evidence for the lack of microbial involvement in lupus [44]. However, the observations by Peng et al [45] that TCR-α−/− MRL-lpr mice develop autoantibodies and lupus-like disease suggest that Fas deficiency in this MRL mouse is sufficient to drive an αβ TCR independent pathway of autoimmunity. In addition, the role of the H-2 complex is minimal in determining survival and end organ damage of MRL-lpr mice [46, 47]. It is also significant that unlike the development of glomerulonephritis in (NZBXNZW)F1 femlae mice, the development of autoimmune glomerulonephritis and vasculitis in MRL/lpr mice is independent of Fc receptor [48]. Thus the conclusion that microbes plays little if any role in the pathogenesis of lupus like autoimmunity in MRL-lpr mice may not be generalized to other spontaneous lupus mouse models and humans. Regardless, it must be kept in mind that the human immune system is constantly exposed to both infectious and non infectious microorganisms. In this context our recent findings on molecular mimics of Ro60, which is another lupus-associated autoantigen, demonstrate that peptides derived from human microbiota hold the potential to induce autoimmune responses [49]. Thus, the possibility that immune responses to microbiota might be involved in the induction and perpetuation of autoimmune responses in SLE deserves serious consideration.

Conclusions

Our study clearly demonstrates for the first time that HLA-DR3 restricted T cells reactive with lupus-associated autoantigen SmD can be activated by molecular mimics. The activation of these T cells cross-reactive with SmD results in the production of anti-SmD and other Lupus related autoantibodies. The data shows the potential of T cell epitope mimicry as one of the mechanisms for initiating autoimmune responses to lupus-associated autoantigens and provides an explanation for strong association of HLA-D region with SLE. It is proposed that lupus-associated HLA-DR/DQ have considerable ability to bind to both mimicry peptides from environmental antigens as well as lupus-associated autoantigens. Over a long period of time, repeated exposures to different microorganisms result in the enrichment of self-reactive T cell repertoire leading to autoantibody production.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by NIH grants P50-AR04522, R01-AR047988, R01-AR049449 to SMF, R01-AI079621 (MPI: USD and SFM), KO1 AR051391(USD).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Umesh S Deshmukh, Email: usd7w@virginia.edu.

Davis L Sim, Email: dsim1@jhmi.edu.

Chao Dai, Email: cd3rg@virginia.edu.

Carol J Kannapell, Email: cjk2p@virginia.edu.

Felicia Gaskin, Email: fg6p@virginia.edu.

Govindarajan Rajagopalan, Email: rajagopalan.govindarajan@mayo.edu.

Chella S David, Email: david.chella@mayo.edu.

Shu Man Fu, Email: sf2e@virginia.edu.

References

- 1.Estes D, Christian CL. The natural history of systemic lupus erythematosus by prospective analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 1971;50:85–95. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197103000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crispin JC, Liossis SN, Kis-Toth K, Lieberman LA, Kyttaris VC, Juang YT, Tsokos GC. Pathogenesis of human systemic lupus erythematosus: recent advances. Trends Mol. Med. 2010;16:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reichlin M. Anticytoplasmic antibodies in SLE: antibodies to cytoplasmic antigens. In: Lahita RG, editor. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. San Diego: Academic Press; 2004. pp. 315–324. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reeves WH, Satoh M, Richards HB. Origins of antinuclear antibodies. In: Lahita RG, editor. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. San Diego: Academic Press; 2004. pp. 401–431. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnett FC, Shulman LE. Studies in familial systemic lupus erythematosus. Medicine (Baltimore) 1976;55:313–322. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197607000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Darlington GA. Disease expression and class II HLA antigens in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 1999;8:466–470. doi: 10.1177/096120339900800610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graham RR, Ortmann WA, Langefeld CD, Jawaheer D, Selby SA, Rodine PR, Baechler EC, Rohlf KE, Shark KB, Espe KJ, Green LE, Nair RP, Stuart PE, Elder JT, King RA, Moser KL, Gaffney PM, Bugawan TL, Erlich HA, Rich SS, Gregersen PK, Behrens TW. Visualizing human leukocyte antigen class II risk haplotypes in human systemic lupus erythematosus. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;71:543–553. doi: 10.1086/342290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hom G, Graham RR, Modrek B, Taylor KE, Ortmann W, Garnier S, Lee AT, Chung SA, Ferreira RC, Pant PV, Ballinger DG, Kosoy R, Demirci FY, Kamboh MI, Kao AH, Tian C, Gunnarsson I, Bengtsson AA, Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S, Petri M, Manzi S, Seldin MF, Ronnblom L, Syvanen AC, Criswell LA, Gregersen PK, Behrens TW. Association of systemic lupus erythematosus with C8orf13-BLK and ITGAM-ITGAXN. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:900–909. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barcellos LF, May SL, Ramsay PP, Quach HL, Lane JA, Nititham J, Noble JA, Taylor KE, Quach DL, Chung SA, Kelly JA, Moser KL, Behrens TW, Seldin MF, Thomson G, Harley JB, Gaffney PM, Criswell LA. High-density SNP screening of the major histocompatibility complex in systemic lupus erythematosus demonstrates strong evidence for independent susceptibility regions. PLoS Genet. 2009;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000696. e1000696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagy G, Koncz A, Perl A. T- and B-cell abnormalities in systemic lupus erythematosus. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2005;25:123–140. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v25.i2.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagata S, Hanayama R, Kawane K. Autoimmunity and the clearance of dead cells. Cell. 2010;140:619–630. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scheinecker C, Bonelli M, Smolen JS. Pathogenetic aspects of systemic lupus erythematosus with an emphasis on regulatory T cells. J. Autoimmun. 2010;35:269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2010.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nickerson KM, Christensen SR, Shupe J, Kashgarian M, Kim D, Elkon K, Shlomchik MJ. TLR9 regulates TLR7- and MyD88-dependent autoantibody production and disease in a murine model of lupus. J. Immunol. 2010;184:1840–1848. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wucherpfennig KW, Allen PM, Celada F, Cohen IR, De Boer R, Garcia KC, Goldstein B, Greenspan R, Hafler D, Hodgkin P, Huseby ES, Krakauer DC, Nemazee D, Perelson AS, Pinilla C, Strong RK, Sercarz EE. Polyspecificity of T cell and B cell receptor recognition. Semin. Immunol. 2007;19:216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graham RR, Ortmann W, Rodine P, Espe K, Langefeld C, Lange E, Williams A, Beck S, Kyogoku C, Moser K, Gaffney P, Gregersen PK, Criswell LA, Harley JB, Behrens TW. Specific combinations of HLA-DR2 and DR3 class II haplotypes contribute graded risk for disease susceptibility and autoantibodies in human SLE. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;15:823–830. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tycowski KT, Kolev NG, Conrad NK, Fok V, Steitz JA. The ever-growing world of small nuclear ribonucleoprotein. In: Gesteland RF, Cech TR, Atkins JF, editors. The RNA World: The Nature of Modern RNA Suggests a Prebiotic RNA. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2006. p. 327. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Migliorini P, Baldini C, Rocchi V, Bombardieri S. Anti-Sm and anti-RNP antibodies. Autoimmunity. 2005;38:47–54. doi: 10.1080/08916930400022715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, Masi AT, McShane DJ, Rothfield NF, Schaller JG, Talal N, Winchester RJ. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:1271–1277. doi: 10.1002/art.1780251101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deshmukh US, Kannapell CC, Fu SM. Immune responses to small nuclear ribonucleoproteins: antigen-dependent distinct B cell epitope spreading patterns in mice immunized with recombinant polypeptides of small nuclear ribonucleoproteins. J. Immunol. 2002;168:5326–5332. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.5326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajagopalan G, Iijima K, Singh M, Kita H, Patel R, David CS. Intranasal exposure to bacterial superantigens induces airway inflammation in HLA class II transgenic mice. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:1284–1296. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.2.1284-1296.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kong YC, Lomo LC, Motte RW, Giraldo AA, Baisch J, Strauss G, Hammerling GJ, David CS. HLA-DRB1 polymorphism determines susceptibility to autoimmune thyroiditis in transgenic mice: definitive association with HLA-DRB1*0301 (DR3) gene. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:1167–1172. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deshmukh US, Bagavant H, Sim D, Pidiyar V, Fu SM. A SmD peptide induces better antibody responses to other proteins within the small nuclear ribonucleoprotein complex than to SmD protein via intermolecular epitope spreading. J. Immunol. 2007;178:2565–2571. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang C, Deshmukh US, Gaskin F, Bagavant H, Hanson J, David CS, Fu SM. differential responses to Smith D autoantigen by Mice woth HLA-DR and HLA-DQ transgenes: dominant responses by HLA-DR3 transgenic mice with diversification of autoantibodies to small nuclear ribonucleoprotein, double-stranded DNA, nuclear antigens. J. Immunol. 2010;184:1085–1091. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sim DL, Bagavant H, Scindia YM, Ge Y, Gaskin F, Fu SM, Deshmukh US. Genetic complementation results in augmented autoantibody responses to lupus associated antigens. J. Immunol. 2009;183:3505–3511. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waters ST, McDuffie M, Bagavant H, Deshmukh US, Gaskin F, Jiang C, Tung KS, Fu SM. Breaking tolerance to double stranded DNA, nucleosome, and other nuclear antigens is not required for the pathogenesis of lupus glomerulonephritis. J. Exp. Med. 2004;199:255–264. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen F, Rowen L, Hood L, Rothenberg EV. Differential transcriptional regulation of individual TCR V beta segments before gene rearrangement. J. Immunol. 2001;166:1771–1780. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geluk A, vanMeijgaarden KE, Southwood S, Oseroff C, Drijfhout JW, deVries RR, Ottenhoff TH, Sette A. HLA-DR3 molecules can bind peptides carrying two alternative specific submotifs. J. Immunol. 1994;152:5742–5748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bordo D, Argos P. Suggestions for "safe" residue substitutions in site-directed mutagenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 1991;217:721–729. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90528-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh H, Raghava GP. ProPred: prediction of HLA-DR binding sites. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:1236–1237. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.James JA, Neas BR, Moser KL, Hall T, Bruner GR, Sestak AL, Harley JB. Systemic lupus erythematosus in adults is associated with previous Epstein-Barr virus exposure. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1122–1126. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200105)44:5<1122::AID-ANR193>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McClain MT, Heinlen LD, Dennis GJ, Roebuck J, Harley JB, James JA. Early events in lupus humoral autoimmunity suggest initiation through molecular mimicry. Nat. Med. 2005;11:85–89. doi: 10.1038/nm1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Putterman C, Diamond B. Immunization with a peptide surrogate for double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) induces autoantibody production and renal immunoglobulin deposition. J. Exp. Med. 1998;188:29–38. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khalil M, Inaba K, Steinman R, Ravetch J, Diamond B. T cell studies in a peptide-induced model of systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Immunol. 2001;166:1667–1674. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arends J, Wu J, Borillo J, Troung L, Zhou C, Vigneswaran N, Lou YH. T cell epitope mimicry in antiglomerular basement membrane disease. J. Immunol. 2006;176:1252–1258. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riemekasten G, Weiss C, Schneider S, Thiel A, Bruns A, Schumann F, Blass S, Burmester GR, Hiepe F. T cell reactivity against the SmD1(83–119) C terminal peptide in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2002;61:779–785. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.9.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Talken BL, Schafermeyer KR, Bailey CW, Lee DR, Hoffman RW. T cell epitope mapping of the Smith antigen reveals that highly conserved Smith antigen motifs are the dominant target of T cell immunity in systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Immunol. 2001;167:562–568. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.1.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fujinami RS, Oldstone MB. Amino acid homology between the encephalitogenic site of myelin basic protein and virus: mechanism for autoimmunity. Science. 1985;230:1043–1045. doi: 10.1126/science.2414848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Getts MT, Miller SD. 99th Dahlem conference on infection, inflammation and chronic inflammatory disorders: triggering of autoimmune diseases by infections. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2010;160:15–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04132.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nedunchezian D, Cook MA, Rakic M. Systemic lupus erythematosus presenting as a non-O:1 Vibrio cholerae abscess. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:1553–1554. doi: 10.1002/art.1780371022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fu SM, Deshmukh US, Gaskin F. Pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus revisited 2011: End organ resistance to damage, autoantibody initiation and diversification, and HLA-DR. J. Autoimmun. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harkiolaki M, Holmes SL, Svendsen P, Gregersen JW, Jensen LT, McMahon R, Friese MA, van Boxel G, Etzensperger R, Tzartos JS, Kranc K, Sainsbury S, Harlos K, Mellins ED, Palace J, Esiri MM, van der Merwe PA, Jones EY, Fugger L. T cell-mediated autoimmune disease due to low-affinity crossreactivity to common microbial peptides. Immunity. 2009;30:348–357. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jarchum I, Pamer EG. Regulation of innate and adaptive immunity by the commensal microbiota. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2011;23:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee YK, Mazmanian SK. Has the microbiota played a critical role in the evolution of the adaptive immune system? Science. 2010;330:1768–1773. doi: 10.1126/science.1195568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maldonado MA, Kakkanaiah V, MacDonald GC, Chen F, Reap EA, Balish E, Farkas WR, Jennette JC, Madaio MP, Kotzin BL, Cohen PL, Eisenberg RA. The role of environmental antigens in the spontaneous development of autoimmunity in MRL-lpr mice. J. Immunol. 1999;162:6322–6330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peng SL, Madaio MP, Hughes DP, Crispe IN, Owen MJ, Wen L, Hayday AC, Craft J. Murine lupus in the absence of alpha beta T cells. J. Immunol. 1996;156:4041–4049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kong PL, Zhu T, Madaio MP, Craft J. Role of the H-2 haplotype in Fas-intact lupus-prone MRL mice: association with autoantibodies but not renal disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2992–2995. doi: 10.1002/art.11308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sekine H, Graham KL, Zhao S, Elliott MK, Ruiz P, Utz PJ, Gilkeson GS. Role of MHC-linked genes in autoantigen selection and renal disease in amurine model od systemic lupus erythematosus. J. immunol. 2006;177:7423–7434. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsumoto K, Watanabe N, Akikusa B, Kurasawa K, Matsumura R, Saito Y, Iwasmota, Saito T. Fc Receptor-Independent development of autoimmune glomerulonephritis in lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:486–494. doi: 10.1002/art.10813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Szymula AM, Scindia YM, Dey P, Bagavant H, Fu SM, Deshmukh US. Molecular mimicry and human microbiota are involved in the initiation of autoimmune responses. Abstract, FOCIS 2011. 2011 http://www.focisnet.org/FOCIS/images/focis2011/focis_2011_scientific_program_v12.pdf.